Abstract

The current hairy cell leukemia (HCL) treatment is excellent, but evidence of cure with purine analogs cladribine and pentostatin, is lacking. Significant long-term immune suppression, particularly to CD4 + T-cells, and declining complete remission rates with each course, make the identification of new therapies an important goal. The anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (Mab) rituximab displays significant activity, and, while causing prolonged normal B-cell depletion, spares T-cells. Recombinant immunotoxins, containing an Fv fragment of a Mab fused to truncated Pseudomonas exotoxin, have shown efficacy in HCL resistant to both purine analogs and rituximab. LMB-2 targets CD25 and can induce remission providing the HCL cells are CD25+. All HCL cells display CD22. Recombinant anti-CD22 immunotoxin BL22, targeting CD22, has shown significant efficacy in phase I and II testing, and avoids prolonged suppression of both normal B- and T-cells. An improved high-affinity version of BL22, termed HA22, is currently undergoing phase I testing.

Keywords: Recombinant immunotoxin, monoclonal antibody, Fv, BL22, LMB-2, HA22

Need for additional therapies

The results of therapy with purine analogs cladribine and pentostatin for hairy cell leukemia (HCL) are excellent, with 85–95% of patients achieving complete remission (CR), only about 40% of patients relapsing by 10 years [1–3], and 75% achieving second CR [1]. However, disease-free survival curves fail to show a plateau even after 10 years, and hence there is no evidence of cure. Moreover, while third and fourth CRs are common with repeated courses of purine analogs, the CR rates decline significantly with each successive course, irrespective of whether the same purine analog is used or not [4,5]. Because a single course of cladribine or pentostatin is reported to suppress CD4+ lymphocytes below the lower limit of normal for a median of 40 or 54 months, respectively [6,7], it may be unsafe to use repeated courses of purine analogs to maintain HCL patients, particularly at short intervals. The use of rituximab, while not approved for HCL, is an important advance because this anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (MAb) spares T-lymphocytes. CR rates among the six reported rituximab studies in HCL (10–25 patients each, total 97) vary from 10 to 54% [8–13]. However, in the 51 patients from five studies who demonstrated a need for treatment based on cytopenias and who had at least one prior purine analog, there were 10 (20%) CRs and 10 (20%) partial responses (PRs) [8–12]. In the largest single trial enrolling 24 such patients, there were 3 (13%) CRs and 3 (13%) PRs [10]. Thus, new treatments are needed for relapsed HCL which have both high efficacy and lack of cumulative toxicity, particularly to T-cells. Recombinant immunotoxins are currently being developed to meet this need.

Recombinant immunotoxins

Protein toxins are among the most potent natural substances known, in that they act catalytically and can therefore kill a cell with a single molecule in its cytoplasm [14]. Plant toxins inactivate ribosomes by preventing their association with elongation factor-1 and −2 (EF-1 and EF-2). Bacterial toxins such as Pseudomonas exotoxin (PE) and diphtheria toxin (DT) induce ADP-ribosylation of EF-2. This leads to protein synthesis inhibition in either case, and cell death by apoptosis [15,16]. Bacterial toxins, which are more often used to fuse to ligands, are naturally made by bacteria in single-chain form, composed of domains for binding and ADP-ribosylation at opposite ends, and a translocation domain in between [16–19]. The orientation of the domains are opposite in PE and DT, with the binding domain at the amino terminus of PE and at the carboxyl terminus of DT. They intoxicate cells by binding to the cell surface, undergoing internalization, unfolding within an acidic vesicle, undergoing proteolytic cleavage within the translocating domain, and translocating to the cytosol where EF-2 is inactivated by ADP-ribosylation [19]. Recombinant toxins are produced by replacing the binding domain with a cancer cell-binding ligand. In denileukin diftitox, approved for relapsed and refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, human interleukin-2 replaces the binding domain of DT at the carboxyl terminus [20–22]. In recombinant immunotoxins, the cell-binding ligand is an Fv fragment, a recombinant antibody containing the variable domains of a Mab [23]. In the recombinant immunotoxin LMB-2, the variable domains of the anti-CD25 Mab are fused together by a peptide linker and then fused to the amino terminus of PE38, a fragment of PE which is missing its binding domain [19,24]. In the recombinant immunotoxin BL22, the variable domains of the MAb RFB4 are fused to PE38, but the Fv is stabilized with an engineered disulfide bond rather than a peptide linker [25–27].

LMB-2 targeting CD25

LMB-2 was the first recombinant immunotoxin reported to be of benefit for HCL, with four (100%) responses out of four patients treated as part of a phase I trial, one of whom had a durable CR [28,29]. The three patients with PR had inadequate treatment due to pneumonia, dose-limiting toxicity and immunogenicity, suggesting that significant clinical activity might be observed in a phase II setting. Unlike purine analogs, myelosuppression and severe lymphopenia were not observed with LMB-2 [28,29], which was expected since normal T-and B-cells have insufficient CD25 expression to be sensitive [30,31]. The most common toxicities of LMB-2 included non-dose limiting hypoalbuminemia, transaminase and alkaline phosphatase elevations, and fever. A disadvantage of targeting CD25 in HCL is that 10% of patients have a variant (HCLv) in which CD25 is absent [32,33], and this variant is over-represented by patients with relapsed/refractory disease after purine analogs. Both HCLv and classic HCL uniformly express high levels of CD22, and have more recently been targeted by the recombinant immunotoxins BL22.

BL22 targeting CD22

In phase I testing, 31 of the 46 patients had HCL relapsed or refractory after purine analogs, and of these 31 patients there were 19 (61%) CRs and 6 (19%) PRs [34,35]. A completely reversible form of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) was observed in four (13%) of the patients, but only during retreatment with a second or third cycle. However, most (58%) of the CRs were achieved with one cycle, suggesting that retreatment was not always necessary or advisable. Therefore, in the phase II trial, patients were observed without retreatment if they achieved CR or at least the complete blood count (CBC) values required for CR, and if not, they were retreated at a lower dose level. One cycle of BL22 induced CR in 25% of 36 patients, and by retreating the 56% of patients who were eligible for retreatment, the CR rate rose to 47%, with an overall response rate of 72% [36]. Compared to the phase I trial, the dose-limiting HUS rate was less than half (6% vs. 13%) and the immunogenicity rate less than one-third (11% vs. 35%). The median CR duration was 5–46+ (median 22+) months, with 76% of 17 CRs ongoing [36]. Response was not significantly related to length of prior purine analog response, but was significantly higher in patients with spleens <200 mm in maximal dimension than in patients with either larger spleens or prior splenectomy. Pharmacokinetic studies showed significant inverse relationships between area under the curve and tumor burden measured by either the log of the HCL count in the blood, or the spleen size. It was concluded that BL22 is highly active in HCL despite prior purine analog treatment and resistance, and that experimental therapy should be considered in patients prior to removing the spleen or allowing it to become massive in size.

HA22, a high affinity mutant of BL22

Patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) were not as sensitive to BL22, attributed to much lower expression of CD22 on CLL compared to HCL cells [35]. To allow a higher percentage of bound immunotoxin to be internalized by CD22 rather than disassociating from this antigen, the off-rate of BL22 was lowered by mutagenesis within the third complementarity determining region of the heavy chain. The resulting anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin HA22 contained three amino acid mutations and bound with 15-fold higher affinity and lower off-rate to CD22, and had improved cytotoxicity [37–39]. HA22 is undergoing phase I testing in HCL, CLL and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The HCL trial has neared completion with excellent results, and a pivotal trial is being planned in this disease.

Approach to patients with relapsed hairy cell leukemia

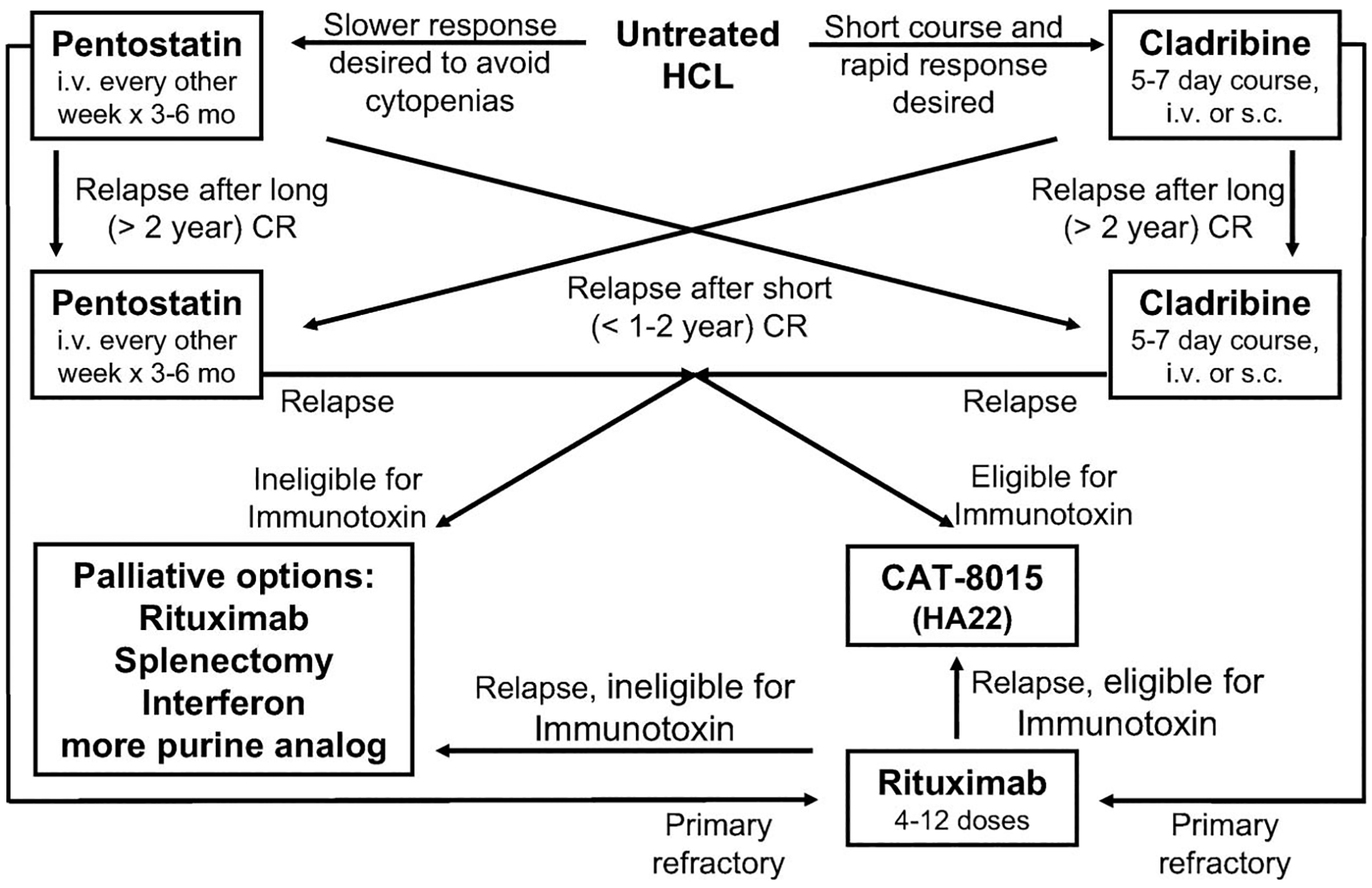

Many different treatment approaches to the relapsed patient exist, and lack of randomized data prevents discounting most of them as inappropriate. A suggested algorithm for the treatment of early and relapsed HCL is shown in Table I. Because of the long-term immunosuppression of purine analogs and their decreased efficacy with retreatment, a general strategy has been to avoid multiple courses of these agents with short time intervals in between. After first relapse with first purine analog response duration less than 1–2 year, or after multiple relapses from purine analog, salvage treatment with rituximab or experimental treatment with LMB-2, BL22 or HA22 (CAT-8015) has shown positive outcomes [28,29, 35,36,40,41,59,60]. Combined treatment with both purine analog and rituximab has been successfully employed in both the 1st line and relapsed setting [5,61–64], although this approach is not standard and long-term suppression of both normal B- and T-cells is expected. Physicians with patients who are eligible for recombinant immunotoxin clinical trials may choose to consider HA22 (CAT-8012) after failure of at least 2 courses of purine analog. Patients with <12 month response to initial purine analog are considered primarily refractory and not appropriate for repeat courses of purine analog, thus their physicians may consider rituximab as 2nd line treatment and HA22 (CAT-8015) thereafter. Interferon is clearly inferior to purine analog for achievement of response [45], and has significant toxicities, but may offer palliation [55]. Splenectomy should be avoided in patients being considered for recombinant immunotoxin experimental treatment [36], but should always be considered in patients with even mild or moderate splenomegaly who have exhausted other options and risk fatal complications of the disease [55,56]. Finally, purine analogs alone or with other agents may be employed in the palliative setting, but their declining potential benefit with repeated use must be considered along with their cumulative and often non-reversible toxicities.

Table I.

HCL-specific open clinical trials.

| Agents | Phase | Line | Center | Cancer.gov NCT# | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cladribine + rituximab | Phase II non-randomized | 1st/2nd | MDA | NCT00412594 | [44] |

| Cladribine + rituximab | Phase II randomized | 1st/2nd | NCI | NCT00781235 | |

| LMB-2 | Phase II | > 2nd | NCI | NCT00337311 | [28,29] |

| BL22 | Phase II retreatment | >3rd | NCI | NCT00850525 | [34–36] |

| HA22 (CAT-8015) | Phase I | > 2nd | NCI, NW Stanford Lodz | NCT00462189 | ASH, 2008, #3160 |

HCL, hairy cell leukemia.

For the two cladribine + rituximab trials, patients begin treatment at MD Anderson (Houston, TX) or at the National Cancer Institute, NIH (Bethesda, MD), respectively, and subsequent treatment may be given by local physicians.

HA22, also called CAT-8015, is administered at NCI, Northwestern (Chicago, IL), Stanford University (Stanford, CA) or at the University of Lodz (Lodz, Poland).

Prevention of relapse by combining rituximab with cladribine

Early treatment with rituximab and cladribine. One hypothesis is that relapse in HCL may be prevented or delayed by eliminating the minimal residual disease (MRD) left over after CR to cladribine. A preliminary report shows excellent activity of rituximab in eliminating MRD when used 4 weeks after cladribine in 13 patients [61]. This trial was not designed to determine whether rituximab should be used during 1st or 2nd line cladribine because comparison with cladribine alone was not done. To determine the benefit of adding rituximab to first or 2nd line cladribine, a randomized study is underway at the National Cancer Institute which also allows patients to be treated by their local physicians. Patients with 0 or 1 prior course of cladribine are randomized separately. Within each of these stratifications, half of the patients receive rituximab beginning with the 1st dose of cladribine, half receive cladribine without rituximab, and all patients receive delayed rituximab at least 6 months later if MRD can be demonstrated in the blood. Thus the 1st goal is to determine if rituximab can decrease the rate of MRD observed in the blood at 6 months, the time point at which patients generally achieve their minimum disease burden after cladribine [65,66]. The 2nd goal is to determine if MRD-free survival is better if rituximab is used up front or delayed. It is quite possible that rituximab may work better if delayed at least 6 months after cladribine when disease is minimal and clumps of cells are more permeable to rituximab. Alternatively, rituximab may work synergistically with cladribine and have optimal activity up front. Regardless of when the rituximab is added in combination with cladribine, we believe that patients with early HCL may benefit from combined treatment and should be referred for the randomized and non-randomized trials of cladribine and rituximab if possible. Because of the cumulative and long term toxicity or purine analogs and the lack of long-term toxicity with recombinant immunotoxins, we believe that patients with multiply relapsed HCL should avoid repeated courses of purine analog and if possible enroll in a clinical trial testing recombinant immunotoxin HA22 (CAT-8015).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart for the suggested treatment of early and relapsed HCL.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NCI, NIH, and work on BL22 and HA22 is supported in part by MedImmune, LLC.

References

- 1.Goodman GR, Burian C, Koziol JA, et al. Extended follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukemia after treatment with cladribine. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:891–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Else M, Ruchlemer R, Osuji N, et al. Long remissions in hairy cell leukemia with purine analogs – a report of 219 patients with a median follow-up of 12.5 years. Cancer 2005;104: 2442–2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jehn U, Bartl R, Dietzfelbinger H, et al. An update: 12-year follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukemia following treatment with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Leukemia 2004;18: 1476–1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saven A, Burian C, Koziol JA, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukemia after cladribine treatment. Blood 1998;92:1918–1926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Else M, Dearden CE, Matutes E, et al. Long-term follow-up of 233 patients with hairy cell leukaemia, treated initially with pentostatin or cladribine, at a median of 16 years from diagnosis. Br J Haematol. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seymour JF, Kurzrock R, Freireich EJ, et al. 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine induces durable remissions and prolonged suppression of CD4+ lymphocyte counts in patients with hairy cell leukemia. Blood 1994;83:2906–2911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seymour JF, Talpaz M, Kurzrock R. Response duration and recovery of CD4+ lymphocytes following deoxycoformycin in interferon-alpha-resistant hairy cell leukemia: 7-year follow-up. Leukemia 1997;11:42–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hagberg H, Lundholm L. Rituximab, a chimaeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of hairy cell leukaemia. Br J Haematol 2001;115:609–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lauria F, Lenoci M, Annino L, et al. Efficacy of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (Mabthera) in patients with progressed hairy cell leukemia. Haematologica 2001;86:1046–1050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nieva J, Bethel K, Saven A. Phase 2 study of rituximab in the treatment of cladribine-failed patients with hairy cell leukemia. Blood 2003;102:810–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas DA, O’Brien S, Bueso-Ramos C, et al. Rituximab in relapsed or refractory hairy cell leukemia. Blood 2003;102: 3906–3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Angelopoulou MK, Pangalis GA, Sachanas S, et al. Outcome and toxicity in relapsed hairy cell leukemia patients treated with rituximab. Leuk Lymphoma 2008;49:1817–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zenhausern R, Simcock M, Gratwohl A, et al. Rituximab in patients with hairy cell leukemia relapsing after treatment with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (SAKK 31/98). Haematol Hematol J 2008;93:1426–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaizumi M, Mekada E, Uchida T, et al. One molecule of diphtheria toxin fragment A introduced into a cell can kill the cell. Cell 1978;15:245–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll SF, Collier RJ. Active site of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A. Glutamic acid 553 is photolabeled by NAD and shows functional homology with glutamic acid 148 of diphtheria toxin. J Biol Chem 1987;262:8707–8711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Ness BG, Howard JB, Bodley JW. ADP-ribosylation of elongation factor 2 by diphtheria toxin. Isolation and properties of the novel ribosyl-amino acid and its hydrolysis products. J Biol Chem 1980;255:10717–10720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang J, FitzGerald DJ, Adhya S, et al. Functional domains of Pseudomonas exotoxin identified by deletion analysis of the gene expressed in E. coli. Cell 1987;48:129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Allured VS, Collier RJ, Carroll SF, et al. Structure of exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa at 3.0 Angstrom resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986;83:1320–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pastan I, Hassan R, FitzGerald DJP, et al. Immunotoxin therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6:559–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams DP, Snider CE, Strom TB, et al. Structure/function analysis of interleukin-2-toxin (DAB486-IL-2). Fragment B sequences required for the delivery of fragment A to the cytosol of target cells. J Biol Chem 1990;265:11885–11889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olsen E, Duvic M, Frankel A, et al. Pivotal Phase III Trial of Two Dose Levels of Denileukin Diftitox for the Treatment of Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:376–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foss F Clinical Experience With Denileukin Diftitox (ONTAK). Semin Oncol 2006;33:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huston JS, Levinson D, Mudgett-Hunter M, et al. Protein engineering of antibody binding sites: recovery of specific activity in an antidigoxin single-chain Fv analogue produced in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988;85:5879–5883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaudhary VK, Queen C, Junghans RP, et al. A recombinant immunotoxin consisting of two antibody variable domains fused to Pseudomonas exotoxin. Nature 1989;339:394–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mansfield E, Amlot P, Pastan I, et al. Recombinant RFB4 immunotoxins exhibit potent cytotoxic activity for CD22-bearing cells and tumors. Blood 1997;90:2020–2026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreitman RJ, Wang QC, FitzGerald DJP, et al. Complete regression of human B-cell lymphoma xenografts in mice treated with recombinant anti-CD22 immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 at doses tolerated by Cynomolgus monkeys. Int J Cancer 1999;81:148–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kreitman RJ, Margulies I, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Cytotoxic activity of disulfide-stabilized recombinant immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) towards fresh malignant cells from patients with B-cell leukemias. Clin Cancer Res 2000;6:1476–1487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Robbins D, et al. Responses in refractory hairy cell leukemia to a recombinant immunotoxin. Blood 1999;94:3340–3348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, White JD, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant immunotoxin Anti-Tac(Fv)-PE38 (LMB-2) in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1614–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kreitman RJ, Chaudhary VK, Kozak RW, et al. Recombinant toxins containing the variable domains of the anti-Tac monoclonal antibody to the interleukin-2 receptor kill malignant cells from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 1992;80:2344–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreitman RJ, Batra JK, Seetharam S, et al. Single-chain immunotoxin fusions between anti-Tac and Pseudomonas exotoxin: relative importance of the two toxin disulfide bonds. Bioconjug Chem 1993;4:112–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matutes E, Wotherspoon A, Catovsky D. The variant form of hairy-cell leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2003; 16:41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matutes E Immunophenotyping and differential diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am 2006;20: 1051–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Bergeron K, et al. Efficacy of the Anti-CD22 Recombinant Immunotoxin BL22 in Chemotherapy-Resistant Hairy-Cell Leukemia. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kreitman RJ, Squires DR, Stetler-Stevenson M, et al. Phase I trial of recombinant immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) in patients with B-cell malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:6719–6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kreitman RJ, Stetler-Stevenson M, Margulies I, et al. Phase II trial of recombinant immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) in patients with hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salvatore G, Beers R, Margulies I, et al. Improved Cytotoxic activity towards cell lines and fresh leukemia cells of a mutant anti-CD22 immunotoxin obtained by antibody phage display. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:995–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Decker T, Oelsner M, Kreitman RJ, et al. Induction of caspase-dependent programmed cell death in b-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by anti-CD22 immunotoxins. Blood 2004;103:2718–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho M, Kreitman RJ, Onda M, et al. In vitro antibody evolution targeting germline hot spots to increase activity of an anti-CD22 immunotoxin. J Biol Chem 2005;280:607–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tallman MS, Zakarija A. Hairy cell leukemia: survival and relapse. Long-term follow-up of purine analog-based therapy and approach for relapsed disease. Transfus Apher Sci 2005; 32:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robak T Current treatment options in hairy cell leukemia and hairy cell leukemia variant. Cancer Treat Rev 2006;32:365–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheson BD, Sorensen JM, Vena DA, et al. Treatment of hairy cell leukemia with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine via the Group C protocol mechanism of the National Cancer Institute: a report of 979 patients. J Clin Oncol 1998;16: 3007–3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lauria F, Bocchia M, Marotta G, et al. Weekly administration of 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine in patients with hairy-cell leukemia is effective and reduces infectious complications. Haematologica 1999;84:22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robak T, Blasinska-Morawiec M, Blonski J, et al. 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine (cladribine) in the treatment of hairy cell leukemia and hairy cell leukemia variant: 7-year experience in Poland. Eur J Haematol 1999;62:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grever M, Kopecky K, Foucar MK, et al. Randomized comparison of pentostatin versus interferon alfa-2a in previously untreated patients with hairy cell leukemia: an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:974–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grever MR. Pentostatin: Impact on outcome in hairy cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin N Am 2006;20:1099–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maloisel F, Benboubker L, Gardembas M, et al. Long-term outcome with pentostatin treatment in hairy cell leukemia patients. A French retrospective study of 238 patients. Leukemia 2003;17:45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnston JB, Eisenhauer E, Wainman N, et al. Long-term outcome following treatment of hairy cell leukemia with pentostatin (Nipent): a National Cancer Institute of Canada Study. Semin Oncol 2000;27:32–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flinn IW, Kopecky KJ, Foucar MK, et al. Long-term follow-up of remission duration, mortality, and second malignancies in hairy cell leukemia patients treated with pentostatin. Blood 2000;96:2981–2986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ribeiro P, Bouaffia F, Peaud PY, et al. Long term outcome of patients with hairy cell leukemia treated with pentostatin. Cancer 1999;85:65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matutes E, Meeus P, McLennan K, et al. The significance of minimal residual disease in hairy cell leukaemia treated with deoxycoformycin: a long-term follow-up study. Br J Haematol 1997;98:375–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cassileth PA, Cheuvart B, Spiers AS, et al. Pentostatin induces durable remissions in hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol 1991;9:243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dearden CE, Matutes E, Hilditch BL, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with hairy cell leukaemia after treatment with pentostatin or cladribine. Br J Haematol 1999;106:515–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rafel M, Cervantes F, Beltran JM, et al. Deoxycoformycin in the treatment of patients with hairy cell leukemia: results of a Spanish collaborative study of 80 patients. Cancer 2000;88: 352–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Habermann TM. Splenectomy, interferon, and treatments of historical interest in hairy cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2006;20:1075–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zakarija A, Peterson LC, Tallman MS. Splenectomy and treatments of historical interest. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2003;16:57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dunn P, Shih LY, Ho YS, et al. Hairy cell leukemia variant. Acta Haematol 1995;94:105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishii K, Katayama N, Maeda H, et al. Successful treatment with low-dose splenic irradiation for massive splenomegaly in an elderly patient with hairy-cell leukemia. Eur J Haematol 2001;67:255–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gidron A, Tallman MS. Hairy cell leukemia: towards a curative strategy. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2006;20:1153–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fanta PT, Saven A. Hairy cell leukemia. Cancer Treat Res 2008;142:193–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ravandi F, Jorgensen JL, O’Brien SM, et al. Eradication of minimal residual disease in hairy cell leukemia. Blood 2006;107:4658–4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Else M, Osuji N, Forconi F, et al. The role of rituximab in combination with pentostatin or cladribine for the treatment of recurrent/refractory hairy cell leukemia. Cancer 2007;110: 2240–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cervetti G, Galimberti S, Andreazzoli F, et al. Rituximab as treatment for minimal residual disease in hairy cell leukaemia. Eur J Haematol 2004;73:412–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cervetti G, Galimberti S, Andreazzoli F, et al. Rituximab as treatment for minimal residual disease in hairy cell leukaemia: extended follow-up. Br J Haematol 2008;143: 296–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bastie JN, CazalsHatem D, Daniel MT, et al. Five years follow-up after 2-chloro deoxyadenosine treatment in thirty patients with hairy cell leukemia: evaluation of minimal residual disease and CD4+ lymphocytopenia after treatment. Leuk Lymphoma 1999;35:555–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wheaton S, Tallman MS, Hakimian D, et al. Minimal residual disease may predict bone marrow relapse in patients with hairy cell leukemia treated with 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine. Blood 1996;87:1556–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]