Abstract

目的

探索血管健康指标(包括颈-股动脉脉搏波传导速度、颈-桡动脉脉搏波传导速度、心踝血管指数和踝臂指数)与冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病(简称冠心病)和脑梗塞的关系,初步评估北京血管健康分级的预测价值。

方法

研究纳入2010—2017年首钢医院血管医学科至少有2次住院记录的受试者,排除基线时血管指标数据缺失且患有冠心病或脑梗塞的患者。建立两个队列,队列1(冠心病)入组467例受试者[平均年龄(63.4±12.3)岁,女性42.2%],队列2(脑梗塞)入组658例受试者[平均年龄(64.3±12.2)岁,女性48.7%],分别应用Cox比例风险回归建立冠心病或脑梗塞的预测模型。

结果

队列1和队列2的中位随访时间分别为1.9年和2.1年,随访期间,队列1中有164例首发冠心病事件发生,队列2中有117例首发脑梗塞事件发生。将4种血管健康指标同时作为连续变量进行多变量调整分析,队列1中,4种指标均有统计学意义(P均<0.05);队列2中,仅心踝血管指数有统计学意义(P<0.05)。未调整模型中,北京血管健康分级对于冠心病和脑梗塞的预测价值均有统计学意义(P均<0.05),而在多变量调整模型中,北京血管健康分级仅对冠心病具有预测价值(P<0.05)。

结论

不同的血管健康指标对于冠心病和脑梗塞的预测价值不同,其中心踝血管指数可能是一种较为稳定的指标。北京血管健康分级对于冠心病具有预测价值,而对于脑梗塞的预测价值还需进一步研究。

Keywords: 心血管疾病, 危险因素, 队列研究, 北京血管健康分级

Abstract

Objective

To explore the predictive value of carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity (CF-PWV), carotid radial artery pulse wave velocity (CR-PWV), cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI), and ankle brachial index (ABI) on coronary heart disease (CHD) and cerebral infarction (CI), and the preliminary validation of Beijing vascular health stratification (BVHS).

Methods

Subjects with at least 2 in-patient records were included into the study between 2010 and 2017 from Vascular Medicine Center of Peking University Shougang Hospital. Subjects with CHD or CI, and without data of vascular function at baseline were excluded. Eventually, 467 subjects free of CHD [cohort 1, mean age: (63.4±12.3) years, female 42.2%] and 658 subjects free of CI [cohort 2, mean age: (64.3±12.2) years, female 48.7%] at baseline were included. The first in-patient records were as the baseline data, the second in-patient records were as a following-up data. Cox proportional hazard regression was used to establish the predictive models of CHD or CI derived from BVHS by multivariable-adjusted analysis.

Results

The median follow-up time of cohort 1 and cohort 2 was 1.9 years and 2.1 years, respectively. During the follow-up, 164 first CHD events occurred in cohort 1 and 117 first CI events occurred in cohort 2. Four indicators were assessed as continuous variables simultaneously by multivariable-adjusted analysis. In cohort 1, CF-PWV, CR-PWV, ABI, and CAVI reached statistical significance in the multivariable-adjusted models (P<0.05). In cohort 2, only CAVI (P<0.05) was of statistical significance. In addition, the higher CF-PWV became a protector of CHD or CI (P<0.05). The prediction value of BVHS reached the statistical significance for CHD and CI in the unadjusted models (all P<0.05), however, BVHS could only predict the incidence of CHD (P<0.05), but not the incidence of CI (P>0.05) in the multivariable-adjusted models. CF-PWV, CR-PWV, ABI, and CAVI were associated factors of CHD independent of each other (P<0.05), only CAVI (P<0.05) was the risk factor of CI independent of the other three.

Conclusion

The different vascular indicators might have different effect on CHD or CI. CAVI might be a stable predictor of both CHD and CI. Higher baseline CF-PWV was not necessarily a risk factor of CHD or CI because of proper vascular health management. BVHS was a potential factor for the prediction of CHD, and further research is needed to explore the prediction value for CI.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Risk factors, Cohort studies, Beijing vascular health stratification

目前血管结构病变(如管腔狭窄或闭塞)被常规用于心血管疾病的风险评估,尽管以往研究已发现动脉功能障碍与心血管疾病的关系,但尚未引起临床重视。一些无创指标已被用来量化评估血管健康,包括踝臂指数(ankle brachial index,ABI)、颈-股动脉脉搏波传导速度(carotid-femoral artery pulse wave velocity,CF-PWV)、颈-桡动脉脉搏波传导速度(carotid-radial artery pulse wave velocity,CR-PWV)、心踝血管指数(cardio-ankle vascular index,CAVI)。ABI是踝部动脉与肱动脉收缩压之比,常作为下肢动脉粥样硬化闭塞的诊断标准之一[1],还是其他血管床发生动脉粥样硬化的提示指标,低的ABI还被认为是西方和亚洲人群心血管疾病的独立预测因子[2,3]。CF-PWV作为动脉硬化评估指标的研究较多,其增高是患病人群和一般人群的心血管疾病危险因子[4,5],目前尚未发现CR-PWV与心血管疾病有关[6,7,8]。CAVI也是动脉硬化的指标之一,但其在检测时不受即刻血压的影响[9],有研究发现CAVI与心血管疾病的危险因素有关[10,11,12,13]。

关于上述指标的研究尚存在以下不足:(1)ABI和CF-PWV的相关研究众多,但是关于CR-PWV和CAVI的研究以及多种指标联合评估的研究较少;(2)大多数研究的是西方人群,关于亚洲人群的研究多是日本人群,关于中国人群的队列研究尚缺乏。一些血管健康指标已被证实为心血管疾病的独立危险因素,用于心血管事件的预测,且血管健康指标联合传统的危险因素能够提高心血管事件的预测能力[14,15,16]。本研究团队在总结了多年的临床及科研经验后,提出了血管健康综合评估系统的概念,并提出了以血管为评估靶点的北京血管健康分级标准(Beijing vascular health stratification, BVHS)[17,18],然而此分级系统尚未被验证其应用价值。

因此,本研究基于医院内数据设计回顾性队列研究,目的在于在中国人群中,探索不同血管健康指标对两种主要心血管疾病——冠状动脉粥样硬化性心脏病(简称冠心病)和脑梗塞(cerebral infarction,CI)预测的联合效应以及相对权重,初步评估BVHS的预测价值。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究人群

本研究设计为基于医院内数据的回顾性队列研究,使用北京血管疾病人群评估研究(Beijing Vascular Disease Patients Evaluation Study,BEST Study)的部分数据。BEST研究(Clinical Trials.gov Identifier: NCT02569268)是一项自2010年在北京大学首钢医院血管医学中心开展的前瞻性队列研究[19]。

收集2010—2017年在首钢医院血管医学科住院就诊人群(涵盖各种血管相关疾病,主要包括高血压、糖尿病、冠心病、脑梗塞和外周动脉疾病等)的医疗数据。

建立两个队列,队列1(冠心病队列),队列2(脑梗塞队列),两个队列的入选标准为:(1)年龄、性别不限;(2)至少有一次住院记录(作为基线数据资料),且在其当次住院后至少有一次住院记录(作为随访记录数据)。

队列1和队列2的排除标准:(1)基线时血管健康指标数据缺失;(2)基线时患有冠心病者(队列1)、患有脑梗塞者(队列2)。

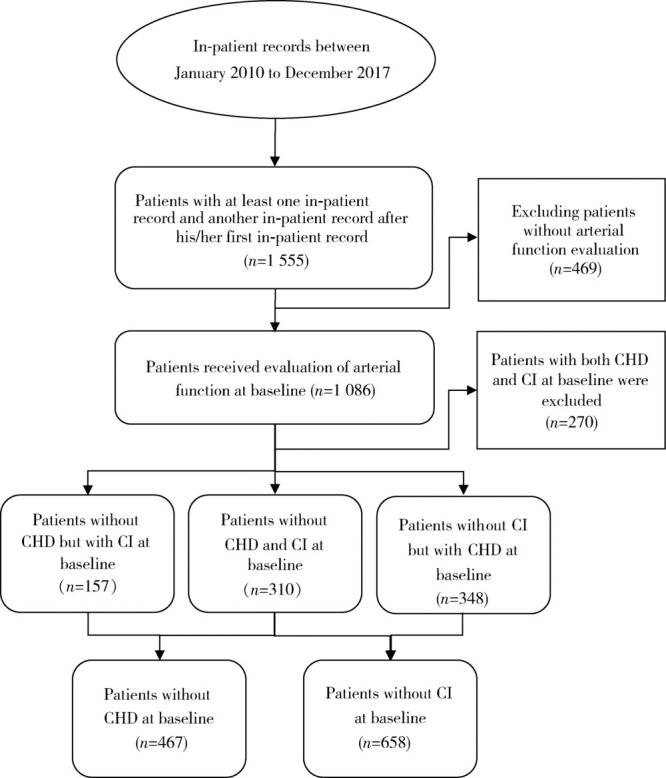

队列1入选467例无冠心病受试者,队列2入选658例无脑梗塞受试者,入选流程图见图1。

1.

受试者入选流程图

Flow diagram of subject inclusion process

CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, cerebral infarction.

BEST研究方案符合1975年《赫尔辛基宣言》,且通过北京大学首钢医院伦理委员会批准(批件号IRBK-2017-017-01),入选受试者均签署书面知情同意书。

1.2. 血管健康指标检查

血管健康指标测量前嘱受检者休息、保持安静并平卧位5~10 min,如运动后需静息20 min,受检者去枕仰卧体位,双手手心向上置于身体两侧。

CF-PWV和CR-PWV使用自动血管功能检查设备(Artech Medical, Pantin, 法国)检测,其原理为脉搏波在动脉系统的两个既定点之间的传播速度通过测量两点之间的传导时间(t)和距离(L)求得,计算公式为PWV(m/s)=L/t。

CAVI和ABI使用血管筛查系统(VS-1000,Fukuda Denshi,日本)检测,将四肢血压袖带缚于被检测者上臂及下肢踝部,将2个心电电极分别置于双腕部以采集心电信号,将心音传感器放置在胸骨上第二肋间的位置,仪器自动检测双侧CAVI和ABI。本研究中,ABI取平均值(因ABI数值反映动脉狭窄闭塞的病变程度,本研究中取双侧平均值用于评估下肢动脉的病变负荷),CAVI取两侧中较大值。

1.3. 心血管危险因素的临床评估和定义

收集记录基线时吸烟、饮酒数据,高血压、糖尿病和高脂血症的诊断数据来自于首次住院时医疗文件记录,身高、体质量、心率、收缩压和舒张压由CAVI设备同时获得,体重指数(body mass index,BMI)=体质量/身高2,平均动脉压(mean arterial pressure,MAP)=2/3舒张压+1/3收缩压。

1.4. 简化的BVHS

BVHS是一种基于血管结构和功能(如动脉内皮功能、动脉僵硬度和动脉狭窄)进行综合评估的新的血管健康评估系统。本研究中,仅用动脉僵硬度和动脉狭窄指标,将BVHS简化为七级评分系统,定义及赋值为: 1: 动脉硬化,右侧CF-PWV>9 m/s或任意一侧CAVI>9; 0: 无动脉硬化,右侧CF-PWV<9 m/s且双侧CAVI<9。

动脉狭窄程度的评估基于影像学检查,包括颅脑磁共振成像血管造影、外周动脉和冠状动脉的X线血管造影、计算机断层扫描血管造影(computed tomography angiography,CTA)或血管超声(颈动脉、锁骨下动脉、下肢动脉、腹主动脉)。如无影像学诊断报告,则被认定为动脉狭窄程度为1,即无血管管腔狭窄,赋值如下:1:无血管管腔狭窄;2:血管管腔狭窄<50%;3:血管管腔狭窄50%~75%;4:血管管腔狭窄>75%。最终简化的BVHS详见表1。

1.

简化的北京血管健康分级赋值

Simplified BVHS system

| Artery stenosis | Arterial stiffness | Simplified BVHS |

| Artery stenosis including peripheral artery and coronary artery detected by vascular ultrasound or computed tomography angiography or angiography. 1, 2, 3, 4, correspond to no vascular lumen stenosis, vascular lumen stenosis<50%, vascular lumen stenosis 50%-75%, vascular lumen stenosis>75%. Arterial stiffness=1, corresponds to CF-PWV>9 m/s or CAVI>9 in either side, and otherwise=0. BVHS, Beijing vascular health stratification. | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 1 | 3 | |

| 3 | 0 | 4 |

| 1 | 5 | |

| 4 | 0 | 6 |

| 1 | 7 | |

1.5. 结局

队列1中主要的结局变量是冠心病,队列2中主要的结局变量是脑梗塞。对于随访的医疗记录,再次核实冠心病及脑梗塞的诊断。冠心病定义为有心肌梗死、明确的心绞痛、复苏的心脏骤停、冠状动脉旁路移植术或血管成形术的病史。脑梗塞的诊断来自于颅脑磁共振检查结果。

1.6. 统计学分析

队列1和队列2中应用同样的统计分析方法,所有受试者按照年龄被分为6组:年龄<40岁、40~49岁、50~59岁、60~69岁、70~79岁和≥80岁。以性别和年龄组特定的中位数作为界定值来定义高或低的血管健康指标,包括CF-PWV、CR-PWV、ABI和CAVI。采用两独立样本t检验和卡方检验比较两组之间的差异,以Cox比例风险模型检验4种血管健康指标以及BVHS综合评估系统与冠心病或脑梗塞之间的关系。本研究以单一血管健康指标或4个血管健康指标同时作为自变量,冠心病或脑梗塞为因变量,调整其他混杂因素,建立如下模型:(1)单一血管健康指标作为二分类变量(高或低)建立多变量调整模型;(2)单一血管健康指标作为连续变量建立多变量调整模型;(3)4个血管健康指标同时作为连续变量建立多变量调整模型;(4)以BVHS建立模型。本研究为将年龄、性别、吸烟、饮酒、BMI、心率、平均动脉压、高血压、糖尿病、高脂血症、基线时脑梗塞(队列1)或基线时冠心病(队列2)进行调整的多变量分析,双侧P<0.05为差异有统计学意义,所有分析均使用R软件(版本3.5.1,奥地利,维也纳,R统计计算基金会)进行。

2. 结果

2.1. 队列1和队列2的一般临床特点

队列1和队列2的中位随访时间分别为1.9年和2.1年,随访期间,队列1中有164例首发冠心病事件发生,队列2中有117例首发脑梗塞事件发生(表2)。

2.

队列1人群和队列2人群的基线特点

Baseline characteristics of cohort 1 and cohort 2

| Variable | Cohort 1 (n=467) |

Cohort 2 (n=658) |

| Values are x±s for continuous variables or % for categorical variables. CF-PWV, carotid-femoral artery pulse wave velocity; CR-PWV, carotid-radial artery pulse wave velocity; ABI, ankle brachial index; CAVI, cardio-ankle vascular index. | ||

| Age/years | 63.4±12.3 | 64.3±12.2 |

| Female/% | 42.2 | 48.7 |

| Body mass index/(kg/m2) | 25.2±3.8 | 25.6±6.1 |

| Heart rate/(beats/min) | 70.3±11.6 | 71.7±42.6 |

| Mean artery pressure/mmHg | 101.8±11.9 | 101.6±14.5 |

| Smoking/% | 30.0 | 26.6 |

| Drinking/% | 27.0 | 23.1 |

| Diabetes/% | 23.3 | 29.7 |

| Hypertension/% | 62.7 | 64.6 |

| Hyperlipidemia/% | 57.8 | 64.2 |

| Coronary heart disease (baseline/endpoint)/% |

52.1/66.1 | |

| Cerebral infarction (baseline/endpoint)/% |

32.8/41.8 | |

| CF-PWV/(m/s) | 11.6±2.9 | 11.6±2.7 |

| CR-PWV/(m/s) | 9.2±1.7 | 9.1±1.8 |

| CAVI | 8.7±1.9 | 8.6±1.9 |

| ABI | 1.02±0.20 | 1.01±0.21 |

| Median follow-up time/years | 1.9 | 2.1 |

| Number of events | 164 | 117 |

2.2. 4种血管健康指标对于冠心病和脑梗塞事件的预测

由表3~6可见,队列1中,将4种血管健康指标分别作为二分类变量进行多变量调整的Cox分析发现,CF-PWV、CR-PWV和CAVI有统计学意义,而ABI并无统计学意义。将4种血管健康指标分别作为连续变量进行多变量调整的Cox分析发现,CF-PWV、CR-PWV和ABI均具有统计学意义,而CAVI无统计学意义。将4种血管健康指标同时作为连续变量进行多变量调整分析,4种指标均具有统计学意义。

3.

队列1中4种血管健康指标分别对于冠心病风险的预测

Risk of coronary heart disease event in cohort 1 in groups classified by four arterial health indicators (high vs. low) and per 1-SD increase in them

| Items | Binary (high vs. low) | Continuous (per 1-SD increase) | |||

| Unadjusted | Multivariable-adjusted | Unadjusted | Multivariable-adjusted | ||

| Multivariable-adjusted model is adjusted for age, gender, smoking, alcohol use, body mass index, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebral infarction at baseline and hyperlipoidemia. CF-PWV, carotid-femoral artery pulse wave velocity; CR-PWV, carotid-radial artery pulse wave velocity; ABI, ankle brachial index; CAVI, cardio-ankle vascular index; SD, standard deviation; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. | |||||

| CF-PWV | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 0.82 (0.60-1.11) | 0.68 (0.48-0.96) | 0.92 (0.78-1.08) | 0.65 (0.54-0.77) | |

| P value | 0.198 | 0.028 | 0.298 | <0.001 | |

| CR-PWV | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 0.64 (0.47-0.87) | 0.70 (0.59-0.83) | 0.70 (0.59-0.83) | 0.64 (0.53-0.76) | |

| P value | 0.004 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ABI | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 0.90 (0.66-1.23) | 1.01 (0.73-1.41) | 0.80 (0.70-0.91) | 0.85 (0.73-1.00) | |

| P value | 0.526 | 0.946 | <0.001 | 0.044 | |

| CAVI | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 1.33 (0.97-1.81) | 1.54 (1.09-2.18) | 1.29 (1.12-1.49) | 1.19 (0.99-1.43) | |

| P value | 0.075 | 0.014 | <0.001 | 0.062 | |

4.

队列2中4种血管健康指标分别对于脑梗塞风险的预测

Risk of cerebral infarction event in cohort 2 in groups classified by four arterial health indicators (high vs. low) and per 1-SD increase in them

| Items | Binary (high vs. low) | Continuous (per 1-SD increase) | |||

| Unadjusted | Multivariable-adjusted | Unadjusted | Multivariable-adjusted | ||

| Multivariable-adjusted model is adjusted for age, gender, smoking, alcohol use, body mass index, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease at baseline and hyperlipoidemia. Abbreviations as in Table 3. | |||||

| CF-PWV | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 0.79 (0.55-1.14) | 0.62 (0.42-0.91) | 1.14 (0.95-1.36) | 0.80 (0.66-0.97) | |

| P value | 0.209 | 0.016 | 0.159 | 0.025 | |

| CR-PWV | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 0.95 (0.66-1.37) | 0.75 (0.51-1.12) | 0.87 (0.72-1.07) | 0.90 (0.73-1.12) | |

| P value | 0.784 | 0.170 | 0.182 | 0.344 | |

| ABI | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 0.97 (0.67-1.39) | 1.01 (0.69-1.49) | 0.86 (0.72-1.01) | 1.04 (0.85-1.27) | |

| P value | 0.852 | 0.949 | 0.076 | 0.697 | |

| CAVI | |||||

| HR (95%CI) | 1.93 (1.32-2.83) | 1.86 (1.27-2.80) | 1.57 (1.36-1.81) | 1.35 (1.12-1.64) | |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.002 | |

5.

队列1中4种血管健康指标同时对于冠心病风险的预测

Risk of coronary heart disease event in cohort 1 per 1-SD increase in four arterial health indicators

| Model | Indicator | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Abbreviations and footnotes as in Table 3. | |||

| Unadjusted | CF-PWV | 0.82 (0.69-0.97) | 0.023 |

| CR-PWV | 0.75 (0.63-0.88) | <0.001 | |

| ABI | 0.78 (0.67-0.90) | <0.001 | |

| CAVI | 1.42 (1.22-1.64) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | CF-PWV | 0.71 (0.59-0.86) | <0.001 |

| CR-PWV | 0.70 (0.57-0.84) | <0.001 | |

| ABI | 0.84 (0.71-0.99) | 0.042 | |

| CAVI | 1.32 (1.11-1.58) | 0.002 | |

6.

队列2中4种血管健康指标同时对于脑梗塞风险的预测

Risk of cerebral infarction event in cohort 2 per 1-SD increase in four arterial health indicators

| Model | Indicator | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Abbreviations as in Table 3. Footnotes as in Table 4. | |||

| Unadjusted | CF-PWV | 1.04 (0.87-1.25) | 0.639 |

| CR-PWV | 0.87 (0.72-1.06) | 0.177 | |

| ABI | 0.86 (0.72-1.03) | 0.105 | |

| CAVI | 1.55 (1.35-1.78) | <0.001 | |

| Multivariable-adjusted | CF-PWV | 0.83 (0.69-1.00) | 0.055 |

| CR-PWV | 0.92 (0.74-1.13) | 0.417 | |

| ABI | 0.99 (0.80-1.23) | 0.947 | |

| CAVI | 1.33 (1.11-1.60) | 0.002 | |

队列2中,将4种血管健康指标分别作为二分类变量和连续变量进行多变量调整的Cox分析发现,只有CF-PWV和CAVI有统计学意义。将4种血管指标同时作为连续变量进行多变量调整分析,只有CAVI具有统计学意义。

2.3. 简化的BVHS对于冠心病和脑梗塞的预测价值

未调整的Cox分析发现,简化的BVHS对于冠心病和脑梗塞的预测均有统计学意义,而在多变量调整的Cox分析中,简化的BVHS仅对冠心病的预测有统计学意义,而对脑梗塞的预测没有统计学意义(表7)。

7.

简化的BVHS对于冠心病和脑梗塞的预测价值

Predictive value of simplified BVHS in prediction of coronary heart disease and cerebral infarction events

| Events | Model | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Coronary heart disease cohort: multivariable-adjusted model is adjusted for age, gender, smoking, alcohol use, body mass index, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cerebral infarction at baseline and hyperlipoidemia. Cerebral infarction cohort: multivariable-adjusted model is adjusted for age, gender, smoking, alcohol use, body mass index, heart rate, mean arterial pressure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease at baseline and hyperlipoidemia. BVHS, Beijing vascular health stratification; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. | |||

| Coronary heart disease |

Unadjusted | 1.20 (1.13-1.27) | <0.001 |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.17 (1.10-1.25) | <0.001 | |

| Cerebral infarction |

Unadjusted | 1.20 (1.00-1.45) | 0.048 |

| Multivariable-adjusted | 1.07 (0.87-1.32) | 0.518 | |

3. 讨论

本研究发现4种血管健康指标CF-PWV、CR-PWV、ABI和CAVI同时是冠心病的独立相关因素,且相互之间独立,而只有CAVI升高是脑梗塞的独立危险因素,且不受其他3种指标的影响。这些结果提示,不同的血管健康指标对于冠心病和脑梗塞的预测价值不同,而且CAVI可能是冠心病和脑梗塞比较稳定的预测指标。此外,本研究分析了BVHS的价值,发现其对于冠心病具有预测价值,而对于脑梗塞的预测价值还需要进一步的研究。

关于血管健康指标的研究较多,但大多数研究仅围绕某一指标进行单独研究,很少研究多种血管健康指标在同一队列中的价值。目前为止,较高的CF-PWV一直被认为是心血管事件的危险因素。一项包括19项研究的荟萃分析估计CF-PWV的风险比(hazard risk, HR)为1.25(每增加1个标准差,95%CI为1.19~1.31),且这些研究均提示较高的CF-PWV是显著的危险因子[5]。然而,本研究中较高的CF-PWV在一些研究分析中并不是危险因素,而表现为冠心病或脑梗塞的保护因子。究其原因,可能是本研究在基线时具有较高CF-PWV的人群被给予了更多的系统性治疗和管理,延缓了CF-PWV的进展,甚至使CF-PWV水平降低,从而导致基线时较高的CF-PWV成为了冠心病或脑梗塞事件的保护因素。由此可见,基线时即使具有较高的CF-PWV水平,但是通过系统管理和治疗,较高的CF-PWV可延缓年龄相关的动脉硬化进展,甚或是逆转,从而导致这部分人群的心脑血管事件发生率较低,也初步说明,仅一次血管健康状况评估并不能反映未来心血管事件的风险,而是要终身评估和维护血管健康,从而降低心脑血管事件的发生。此外,CF-PWV指标在检测时容易受到检测时即刻血压变化的影响,本研究结果也初步证实CAVI是一种更加稳定的指标,本研究中对ABI和CAVI的研究结果与既往其他研究结果一致,通常情况下,截点值0.9被用来评估ABI的高低。Ohkuma等[2]通过分析个体数据的荟萃分析研究发现,与ABI为1.10~1.19相比,ABI≤0.9对于心血管事件的HR为1.60,Hong等[20]的荟萃分析中发现了更大的HR为2.22。本研究中,血管健康指标用年龄和性别校正的中位数来作为截点值,而不是用特定的截点数值,这样不同的指标分析结果都以类似的方式展示。不论是作为二分类变量还是连续变量,较低的ABI都是冠心病的显著危险因子,而其对于脑梗塞并无统计学意义。本研究中CAVI对于冠心病和脑梗塞的HR估测值与Satoh-Asahara等[13](HR=1.44,每增加一个标准差,95%CI:1.02~2.02)和Sato等[12](HR=1.126,每增加一个标准差,95%CI:1.006~1.259)的研究结果类似。

本研究团队在2015年提出了新的血管健康分级——BVHS标准[18],本研究中简化了BVHS,初步分析结果发现,其对于冠心病的预测是一个有效的风险评估系统,而对于脑梗塞的预测价值还需要进一步研究确定。

本研究发现,4种血管健康指标同时是冠心病和脑梗塞的预测因子,且相互之间独立,承担不同的权重,其中CAVI是一种更为稳定的指标,此外,通过有效的血管健康管理和干预,即使基线时较高的CF-PWV水平也并不一定是心脑血管事件的危险因素。BVHS在中国人群中对于冠心病具有预测价值,而对于脑梗塞的预测价值尚需研究。今后将进行进一步的前瞻性队列研究,以验证本研究结果,并不断完善BVHS分级系统。

本研究有以下局限性:首先,数据收集并未按照标准的队列研究设计标准收集,而是利用医院现有数据进行分析,本研究的事件发生率较高,原因主要是由回顾性构建队列所造成,与队列构建方法和入组标准有关。本研究入组标准主要是患者需要有至少2次住院记录,第一次作为基线,第二次作为随访,这样就导致了队列人群事件发生率过高的问题,因为那些不发病的患者未回来住院,也就不在队列里,这是本研究的一个重要不足。其次,随访并未经过严格的研究设计,基线后,将每位受试者的每次住院就诊记录作为随访数据,因此有可能此人的心血管事件在患者此次来医院前就已经发生,或者选择了其他医院就诊。第三,本研究仅入选心血管疾病高危人群(主动就诊患者),因此研究结果可能并不适用于一般人群。

尽管本研究并未经严格的方案设计和实施,但对于无创血管健康评估指标建立的综合评估系统和分级标准的临床应用价值进行了初步探索,并得到了较好的结果,因此,本结果对于后续进行严谨方案设计的研究开展,提供了研究价值。

Funding Statement

北京中医药科技发展资金(NQ2016-07); 北京市卫生与健康科技成果和适宜技术推广项目(TG-2017-66); 北京大学首钢医院院内基金(2017-hospital-clinical-01); 北京大学首钢医院院内基金(SGYYZ201610); 北京大学首钢医院院内基金(SGYYQ201605); 北京市卫生局首都卫生发展科研专项(2011-4026-02); 石景山科技计划项目

Capital Project of Scientific and Technological Development of Traditional Chinese Medicine in Beijing(NQ2016-07); Beijing Health Scientific and Technological Achievements and Appropriate Technology Promotion Project(TG-2017-66); Key Clinical Projects in Peking University Shougang Hospital (2017-hospital-clinical-01); Key Clinical Projects in Peking University Shougang Hospital (SGYYZ201610); Key Clinical Projects in Peking University Shougang Hospital (SGYYQ201605); Capital Funds for Health Improvement and Research(2011-4026-02); Science and Technology Plan Project of Shijingshan District Committee of Science and Technology

Contributor Information

周 晓华 (Xiao-hua ZHOU), Email: azhou@math.pku.edu.cn.

王 宏宇 (Hong-yu WANG), Email: dr.hongyuwang@foxmail.com.

References

- 1.Winsor T. Influence of arterial disease on the systolic blood pressure gradients of the extremity. Am J Med Sci. 1950;220(2):117–126. doi: 10.1097/00000441-195008000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohkuma T, Ninomiya T, Tomiyama H, et al. Ankle-brachial index measured by oscillometry is predictive for cardiovascular disease and premature death in the Japanese population: An individual participant data meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2018;275:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heald CL, Fowkes FG, Murray GD, et al. Risk of mortality and cardiovascular disease associated with the ankle-brachial index: Systematic review. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189(1):61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong Q, Hu MJ, Cui YJ, et al. Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in the prediction of cardiovascular events and mortality: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Angiology. 2018;69(7):617–629. doi: 10.1177/0003319717742544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Willum-Hansen T, Staessen JA, Torp-Pedersen C, et al. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113(5):664–670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niiranen TJ, Kalesan B, Larson MG, et al. Aortic-brachial arte-rial stiffness gradient and cardiovascular risk in the community: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension. 2017;69(6):1022–1028. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell GF, Hwang SJ, Vasan RS, et al. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2010;121(4):505–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.886655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tillin T, Chambers J, Malik I, et al. Measurement of pulse wave velocity: site matters. J Hypertens. 2007;25(2):383–389. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280115bea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirai K, Utino J, Otsuka K, et al. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter; cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13(2):101–107. doi: 10.5551/jat.13.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laucevišius A, Ryliškytè L, Balsytè J, et al. Association of cardio-ankle vascular index with cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular events in metabolic syndrome patients. Medicina (Kaunas) 2015;51(3):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsushita K, Ding N, Kim ED, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index and cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective and cross-sectional studies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2019;21(1):16–24. doi: 10.1111/jch.13425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato Y, Nagayama D, Saiki A, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index is independently associated with future cardiovascular events in outpatients with metabolic disorders. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23(5):596–605. doi: 10.5551/jat.31385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satoh-Asahara N, Kotani K, Yamakage H, et al. Cardio-ankle vascular index predicts for the incidence of cardiovascular events in obese patients: a multicenter prospective cohort study (Japan Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome Study: JOMS) Atherosclerosis. 2015;242(2):461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallée A, Petruescu L, Kretz S, et al. Added value of aortic pulse wave velocity index in a predictive diagnosis decision tree of coronary heart disease. Am J Hypertens. 2019;32(4):375–383. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpz004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Velescu A, Clara A, Peñafiel J, et al. Adding low ankle brachial index to classical risk factors improves the prediction of major cardiovascular events. The REGICOR study. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241(2):357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gronewold J, Hermann DM, Lehmann N, et al. Ankle-brachial index predicts stroke in the general population in addition to classical risk factors. Atherosclerosis. 2014;233(2):545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.中国医药教育协会血管医学专业委员会, 中华医学会北京心血管病学分会血管专业学组, 北京大学医学部血管疾病社区防治中心. 中国血管健康评估系统应用指南. 中华医学杂志. 2018;98(37):2955–2967. [Google Scholar]

- 18.王 宏宇, 刘 欢. 新的血管健康分级标准与血管医学. 心血管病学进展. 2015;36(4):365–368. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H, Liu J, Zhao H, et al. The design and rationale of the Beijing Vascular Disease Patients Evaluation Study (BEST study) Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;7:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.conctc.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong JB, Leonards CO, Endres M, et al. Ankle-brachial index and recurrent stroke risk: meta-analysis. Stroke. 2016;47(2):317–322. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]