Short abstract

The study addresses the needs of Scottish kinship carers of teenage children who have been identified as being in need of extra support. It designs and tests an appropriate support programme, defined as CARE. The CARE intervention study reported here applied the Six Steps for Quality Intervention Development framework, a pragmatic, evidence-based framework. The Six Steps for Quality Intervention Development framework comprises six steps: the first three steps seek to reveal the concerns of the kinship carer group and to generate a theory of change; the remaining three steps generate a theory of action for the intervention, and subsequently for its implementation. There were three main benefits reported: first, the self-care techniques had a reportedly positive stress-reduction effect on kinship carers, and in their dealings with their teenager; second, kinship carers reported an increased self-awareness of their communication or 'connectedness' with their teenager; and third, there was a reported positive impact upon behaviour control as a result of the stress-reduction and improved connectedness. The development of the CARE intervention programme suggests that the Six Steps in Quality Intervention Development provides a useful methodological underpinning for intervention procedures which can be applied in a range of public health and social work settings.

Keywords: Stress, relationship, methodology, kinship care, intervention, older adults

Introduction

Good-quality parenting and caring has the potential to improve the health of teenagers and their susceptibility to illness in later life (Stewart-Brown, 2012). The use of alcohol, drug-substances and tobacco, as well as sexual-risk behaviour among teenagers, can all be reduced by successful parenting interventions (Ford et al., 2013; Scott et al., 2014). When birth-parents are struggling, relatives may offer to help, or social services may request their help as an alternative to placing the child in foster care. These relatives or close friends are known as kinship carers, defined as ‘(a) a person who is related to the child; or (b) a person who is known to the child and with whom the child has a pre-existing relationship' (Scottish Government, 2009). Farrugia’s (2016) Analysis of Scottish Government Social Work statistics, 2014–15 stated that the number of children in formal kinship care in Scotland was 4158, a significant 27% of the total looked-after children population. However, these kinship figures only capture children who are formally ‘looked-after’ by family and friends, which is a permanent arrangement with a local authority through a ‘Kinship Care Order’. ‘Non-looked-after’ kinship care is an informal arrangement between the child’s parents and the kinship carer (Mentor, 2017). Citizens Advice Scotland (2016) estimate that there are more than 13,000 formal and informal children in kinship care. The presumed advantages of kinship care are that it preserves family identity and access to other relatives, and that it lessens the trauma often associated with foster care (Cuddeback, 2004: 634).

In Scotland, public expenditure on kinship care is less than that on foster care. Kinship carers receive benefits to cover accommodation and maintenance, in order to provide an allowance for a child equivalent to that of the allowance given for a child placed with a foster carer (Scottish Government, 2016). This benefit is roughly £200 per child per week (Falkirk Council, 2016). However, there are two caveats. First, not all kinship carers receive the benefit – only formal kinship carers and some informal kinship carers (Scottish Government, 2016). Second, foster care fees are not included in the agreement and are not received by kinship carers (Scottish Government, 2016). Foster carer costs, therefore, are significantly higher than kinship carer costs. In 2005, the cost of foster care services in Scotland was £605 per child per week (Tapsfield and Collier, 2005); more recently in 2010, the cost of foster care across the UK was £676 per child per week (Berridge et al., 2012). We can assume that costs will have increased again seven years on from the 2010 figure. Important to note, moreover, is that this is not the full cost of keeping a child in foster care, as it does not include the social work costs and additional services which may need to be provided. Many kinship carers see social workers much less frequently than do foster carers, so again the cost to the local authority (of kinship care) is less than for foster care. When it comes to comparing the cost of supporting a child in residential care versus kinship care, the difference is even more striking. According to Audit Scotland (2010), the average cost of residential care was £3000 per child per week, which is some £156,250 per annum.

Kinship carers tend to live in materially deprived areas, have relatively low educational achievement, and are less healthy than the average population (Houston et al., 2017). The most common reasons for relatives becoming kinship carers are when birth-parents abuse or abandon a child, have drug and alcohol problems, are incarcerated, are ill, or have died. A child may also be given kinship care when there is domestic violence (Houston et al., 2017: 8). These difficult circumstances can present many challenges for both the carer and the child. Those kinship carers who look after teenage children – and who are the focus of this study – may have to deal with behaviour on the part of teenagers which may include, for example, staying out late, behaving in a rude manner, taking drugs and alcohol, or resorting to violence and aggression.

In current parenting interventions, the emphasis is usually on the teenager, not the parent (in this case the kinship carer). The aim here has been to address this omission: that is to say, by focusing the intervention programme – defined hereafter as the CARE programme – on the kinship carer, we seek to improve the lives of both the kinship carer and the teenager. It is important to make clear that we understand kinship carers to be a parenting group. Grandparents – usually grandmothers – comprise the largest percentage of kinship carers in the UK (Cuddeback, 2004). This accords with European data which found that maternal grandmothers, followed by maternal grandfathers, provided the most care for their grandchildren (Danielsbacka et al., 2011). Grandparental kinship carers report high levels of stress (Dunne and Kettler, 2008; Farmer, 2009: 340; Houston et al., 2017: 12; Leder et al., 2007; Orb and Davey, 2005). Our premise is that carers are likely to feel better-equipped in their caring role if their stress levels are reduced, and if they are supported in their own wellbeing. The aim here is to apply to kinship care in Scotland an intervention development framework derived from the Six Steps in Quality Intervention Development (6SQuID) (Wight et al., 2015).

Six Steps in Quality Intervention Development

The 6SQuID framework is a pragmatic, evidence-based, co-produced, six-step framework for intervention development. It was recently developed in the field of public health, but it has wider applicability to other disciplines. It has been applied here to the area of kinship care, and therefore it is of relevance to social work. The framework comprises six steps, but can be categorised into two broad phases, and the paper will deal with each, in turn. The first phase focuses upon the nature of the problem (in this case, how to support the kinship-carers of teenage children), its causes, the factors which are open to modification, and the techniques which will effect beneficial changes. The second phase purports to clarify how the changes will be delivered, and it develops, tests and adapts the intervention programme at issue. In addition, some of the possible implications of the findings for public policy are considered. The research setting is Scotland.

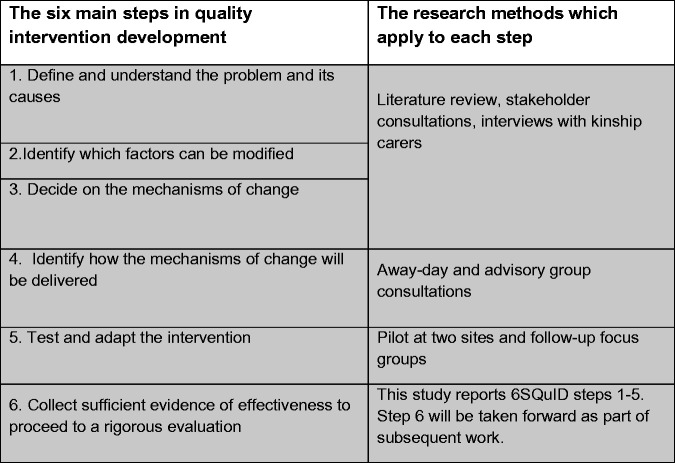

In terms of applying the 6SQuID framework to this study, briefly, the first three steps within the framework sought to bring to the surface the extent of the challenges that kinship carers face, including their concerns. This helped to generate a ‘theory of change' of how change could be achieved. The remaining three steps involved identifying, implementing and testing strategies that are most likely to affect change. The framework, and a summary of how it was applied in this study, is depicted in Figure 1. This study deals with Steps 1–5 (Step 6 requires a separate evaluation study).

Figure 1.

Six 6SQuID steps in quality intervention development and methods used in this study (derived from Wight et al., 2015).

6SQuID: Six Steps in Quality Intervention Development.

Each step of the process informs subsequent steps, and therefore it is necessary, both logically and chronologically, to describe and to report the methods and results for each step prior to subsequent steps, in turn. The main body of the paper has not, therefore, been structured in a manner that separates all the ‘methods' from all the ‘results' in two separate sections.

The CARE programme: First phase

The first three essential steps of the 6SQuID framework broadly allow for a theory of change to be generated which will inform the subsequent development, testing and adaptation of the CARE intervention. These three steps in the framework – and their respective research methods and results – are now reported in sequence. Taken together, the empirical aspects of this part of the study fall within an interpretive paradigm, and they focus on making explicit the everyday endeavours and concerns facing these kinship carers. That done, it was possible to infer from the data what the 6SQuID framework calls a ‘theory of change'.

6SQuID Step 1: Define and understand the problem and its causes

In order to define the problem and its causes, and to identify which factors are malleable and can be modified as part of the intervention, three sources of data were collected and analysed: first, a literature review of effective interventions for parents in general was undertaken; second, interviews with kinship carers were conducted in order to identify additional needs; and third, stakeholder consultations were held to identify a specific population group. These are now considered in turn.

We referred to a previous literature review of interventions involving parents which aimed to reduce the use of alcohol, drugs and tobacco by adolescents (Ford et al., 2013). From this it was inferred that there are two factors which are important for parenting teenage children: ‘connection' and ‘behaviour control'. ‘Connection', or bonding, refers to ‘the emotional attachment and commitment a child makes to social relationships in the family, peer group, school, community, or culture' (Markham et al., 2010: S23). ‘Behaviour control' refers to aspects of the parent–child relationship related to managing behaviour; for example, boundary-setting and conflict. Although the literature review identified two general factors that our intervention should target in order to influence kinship carers' roles – namely, ‘connection' and ‘behaviour control' – we recognised that kinship carers may also have additional needs.

In order to ensure that we addressed these needs, we also conducted semi-structured interviews with kinship carers. The kinship carers were recruited through a national third-sector organisation, and were offered a small monetary incentive to take part. The University Research Ethics Group approved this study. There were ten participants, of whom one was male. Throughout this report, pseudonyms have been used, and place-names have been removed. All of the participants were grandparents, aged between 50 and 70 years, mainly working class in background, and all living in and around a large city in Scotland. We do not have data to say if they were formal or informal kinship carers. Six individual interviews were conducted in participants' homes, and two paired-interviews were held at a community venue. Interviews lasted approximately 75 minutes and were audio-recorded. The topic guide was semi-structured, and was based on discussions with stakeholders and advisory group members. The interviews were transcribed, and entered into NVivo to facilitate analysis. Thematic framework analysis was undertaken. Mapping and interpretation of themes took place whereby all relevant data-items were matched to codes, and a selection of quotations, which illuminated the themes, was then extracted for this report. A consensus within the research team was reached on the most representative interpretation of the data. Having consulted the kinship carers, the research team decided not to include at this stage the teenagers being cared for. The kinship carers advised that their teenage grandchildren would not be interested in, or comfortable working with, a researcher on the project.

Finally, in order for our intervention to be most useful at the policy-and-practice level, we aimed to ensure that it addressed an existing unmet need. Stakeholder consultations were conducted with third-sector organisations, and with our advisory group members – comprising policymakers, practitioners and academics – in order to identify a target-group for our intervention, namely kinship carers.

Four themes emerged: how participants came to be carers; the impact of family circumstances on teenagers’ emotions and behaviours; wider family issues; and carers’ experiences of stress. These themes are now considered sequentially, with typical illustrative examples being provided, as appropriate.

How participants came to be carers

Participants often came to be carers as a result of having to deal with a range of extremely difficult circumstances. Two examples typify the range of issues facing the kinship carers. In the first, Jennifer and John are kinship carers, both in their sixties. They had two daughters, Kelly and Moira. When Moira was eight years-old, she was killed in a traffic accident. Shortly after her sister’s death, Kelly – who at that time was 12 years-old – began drinking alcohol. Since that age Kelly – now in her forties – had struggled with an alcohol addiction. Kelly had three sons with her partner, Mark, but over time they were removed by social services. Those three sons, aged between 16 and 26 years, now live with their grandparents, Jennifer and John. The boys reportedly sleep all day and get up at night when Jennifer and John go to bed. They have no qualifications, job or social network. Neither Jennifer nor John are in good health: both have debilitating conditions. Jennifer needs a mobility scooter but cannot afford one.

Rose – another kinship carer – has two adopted children, Jenny and Rob. Jenny has severe learning disabilities, and is now in her late thirties. She lives with and is cared for by Rose. Rob – now in his forties – married a woman called Anna. Together Rob and Anna had three sons and one daughter. Rob became an alcoholic and Anna a drug addict, and in time their four children (three of whom were teenagers) were removed by social services. About the same time as the children were removed, Rose’s husband died. Social services approached Rose and asked if she would become a carer for one or two of Rob and Anna’s children. Rose said that she couldn’t possibly choose only one of the two children, and instead agreed to take all four. All four of Anna and Rob’s children have learning disabilities and emotional and behavioural problems. These two typical examples show that relatives often became kinship carers as a result of having to deal with bereavement, addiction, negative peer influence, addiction, disability, and medical complications in their families.

The impact of family circumstances on teenagers’ emotions and behaviour

The looked-after teenagers were in need of additional emotional, behavioural and learning support, due to challenging family circumstances. Often, issues are interlinked, causing problems of communication, conflict and behaviour control. This is illustrated below in the interview with Margaret, a grandmother looking after Shelly, a teenager with learning and behavioural issues.

I (Interviewer) So can you tell me what it was like for you when you first became a carer of Shelly?

Margaret: Well at first, I was grieving for Jenny [Margaret’s daughter] and looking after Shelly [granddaughter]. And … with her being a bairn (child), how could you explain to her, ken, that her ma wasn’t going to come back home to her. But, I mean, she’s doing well now. She’s 13. And she gets on well with everybody, ken…She’s got a wee bit of learning difficulties and that just now, ken, her writing and that but she’s getting a lot of help at the school.

I: What is your relationship like with Shelly?

Margaret: Aye, she’s…ken, sometimes she goes into moods and, ken, stomps away up the stair, banging doors, kicking them, tearing the wallpaper, ken. But then she comes out of them as quick as she goes in them, ken.

I: Yeah. And what do you do when she’s in a mood like that?

Margaret: I just sit down here and let her do it, ken…because once I tried to stop her and she hurt me… ken, and…she kicked me doon the stair, but I think she regretted it, ken. And she couldn’t say enough, ken, oh granny, I’m sorry.

Wider family-related issues

Most of the participants faced wider family-related difficulties, in particular difficult relationships with the birth-parents of the teenagers whom they cared for, and/or with other in-laws. This was Laura's situation: she faced what she felt to be exhausting concerns with the biological mother of the two boys for whom she was caring. The two boys still saw their mother regularly and ‘dote on her’. Laura stated that she puts great effort into establishing rules and boundaries. However, when they go to spend the weekend with their mother, Laura felt all that hard work was wasted because the mother has no rules or boundaries whatsoever with the boys. In their eyes, Laura reported, their mother is the fun one whom they want to be with all the time. Laura no longer feels able to be their ‘granny’.

Carers’ experiences of stress

The kinship carers were dealing with particularly difficult situations. Stress was evident, as illustrated below.

I: And what about emotionally? Are there any challenges you feel you face as a carer?

Fiona: Well they’re teenage kids that are away from their parents. There are bound to be issues. But Tom [the grandson], you know, he’s not so bad now, but for a while…he was frustrated. But he would go out and he’d hit a tree. But he would take his temper out on a tree. Whereas Lisa [the granddaughter] goes, bounces on the trampoline. Or she goes out and sits on the box and talks to the hens. But you can see the kids can be frustrated, I think. They’re not with mum and dad all the time. And it must hurt to see mum, the way she is [with a severely debilitating condition].

I: And what about for you in terms of frustrations – is that something that you experience?

Fiona: Just get on with it. To start with when you first get the kids for the first year or so, there’s a lot of crying when driving the car, a lot of crying when you’re in the bath…sitting in the bath with tears to drown you. Then you just have to realise that you’ve got to get yourself together and get on with it.

I: And what does it feel like?

Fiona: You just feel frustrated. Ready to scream, but it’s not going to do any good, so what’s the point? You just…you know, you have a bubble to yourself. You go to the toilet and have a bubble where they don’t see because the kids would get upset … You have to put on a face for the kids because they would get upset if you didn’t.

To summarise, Step 1 of the 6SQuID framework is concerned with understanding the challenges carers face and the ‘theory' of their causes. Kinship carers have often come to be in the role through having to deal with extremely difficult circumstances: without exception, the teenagers who were being cared for were in need of extra emotional, behavioural and learning support, impacting upon communication, conflict and behaviour control with the kinship carer. Kinship carers were dealing also with wider family concerns, in particular difficult relationships with the birth-parents of the teenagers for whom they cared; and the finding that underpinned and was connected to all three of the above findings was that kinship carers experienced and reported high levels of stress.

6SQuID Step 2: Identify which factors can be modified

Based on the factors identified in Step 1, and from the previous literature review (Ford et al., 2013), the key modifiable factors which the intervention would target were: connection, behaviour control (with emphasis on a conflict-management component) and stress reduction.

6SQuID Step 3 – Decide on the mechanisms of change (theory of change)

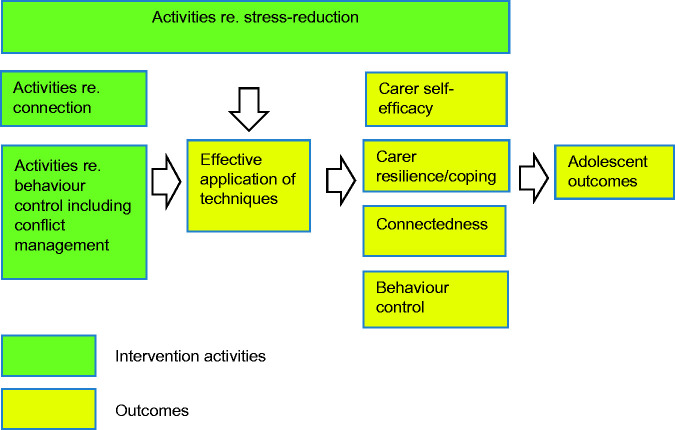

The final stage in the development of the first phase of the CARE programme was informed by Step 3 of the 6SQuID framework. This step involved identifying the techniques that will bring about change, and the intended outcomes deriving from them (Figure 2). This was developed based upon findings from Steps 1 and 2, and from discussions with the advisory group.

Figure 2.

Theory of change.

In essence, we specified that in order for our core intervention activities (related to connection and behaviour control) to be applied effectively, it would be essential that carers were better able to cope with immediate stressors. We propose that improved stress-reduction creates an emotional space whereby carers can absorb intervention content and apply it more effectively to their own benefit and to those for whom they care. We turn now to the second phase of the development and implementation of the CARE programme, again showing how it was informed by Steps 4 and 5 of the 6SQuID framework (Figure 1).

The CARE programme: Second phase

The first phase of the development of the CARE programme was informed by Steps 1–3 of the 6SQuID framework, and in essence it constructed a theory of change. It surfaced those modifiable factors which were open to intervention. Phase two of the CARE programme is informed by Steps 4 and 5 of the 6SQuID framework. It presents and test a theory of action: that is, it refers to how change will be realised in practice. It goes beyond the mere collection and collation of perceptions. Ford et al.'s (2013) review of interventions found that they are more likely to be effective if they satisfy the following criteria: they are delivered in a community or home setting; they are provided by a trained deliverer; they contain activities to promote connection and behaviour control; they consist of at least four weeks' contact time; and they are informed by established theories of human behaviour. In developing our intervention components, we therefore aimed to ensure that these criteria were met. It was at this juncture that a name for the intervention was agreed by the advisory group for the project: CARE.

6SQuID Step 4: Clarify how the mechanisms of change will be delivered

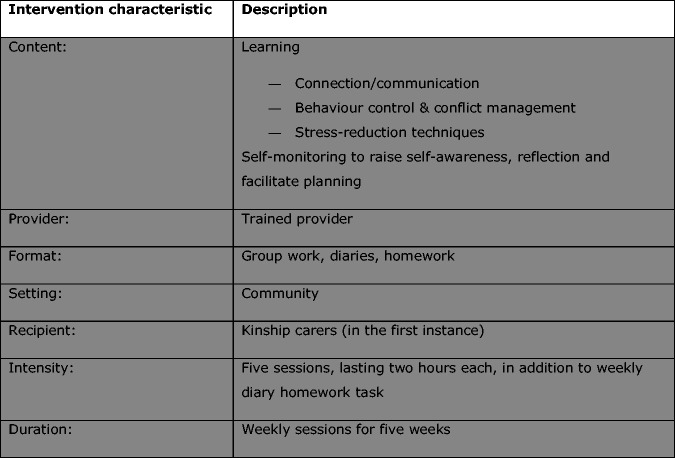

In order to inform Step 4, the advisory group was consulted and an away-day with ten kinship carers was hosted. At the away-day, the first draft of the intervention components was presented in order to assess their acceptability, to seek general feedback and to make any necessary refinements. The away-day also generated feedback in helping to develop stress-reduction techniques with the carers. As stated previously, in order for our core intervention activities (related to connection and behaviour control) to be applied effectively, it was essential that the carers themselves were better able to cope with immediate stressors. Mind-body stress-reduction techniques purport to shift the nervous system from a stressed state of fight-flight-freeze into a relaxed state of rest-digest (Van der Kolk, 2014). Figure 3 shows an outline of the intervention components that we sought feedback on during the away-day.

Figure 3.

Characteristics of the CARE intervention.

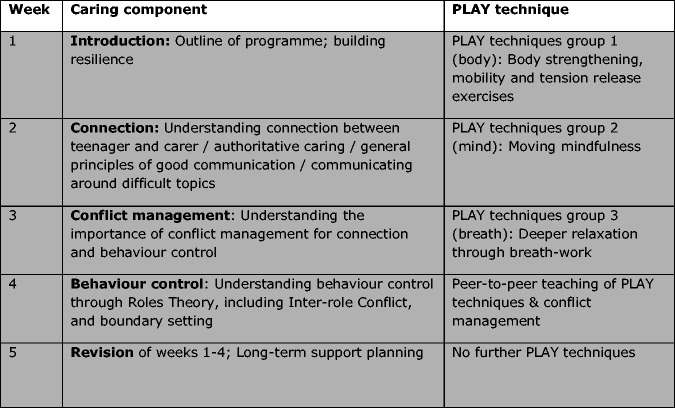

Feedback was generally positive. The latter part of the away-day was spent seeking feedback related to stress-reduction and conflict-management techniques in order to design appropriate techniques for the intervention. A holistic health consultant attended, working with the carers to design personalised stress-reduction techniques. These are referred to within the intervention as Please Look After Yourself (PLAY) techniques. They are organised into three groups, addressing body, mind and breathing respectively, as follows. First, the goal is to release tension in the body, so that the muscles can relax. Second, a state of relaxation is achieved by techniques which focus the mind on the present moment, and reduce the anxiety that comes from worrying about the past or the future. Third, breathing techniques promote further, deeper relaxation. The holistic health consultant also worked with the carers to develop appropriate conflict-management techniques. Following the away-day, a final version of the intervention was developed and agreed by the advisory group. It was decided to introduce PLAY techniques at the start of each weekly session, followed by the caring components (connection and behaviour control/conflict management). The rationale for this was that such a structure would emphasise the importance of the carers’ own wellbeing, since this had been identified as a key concern during Step 2. An intervention manual was produced, which is outlined in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Intervention content, by week.

6SQuID Step 5: Test and adapt the intervention

A pilot study was conducted at two sites, with two rounds of follow-up focus groups. We worked with a family-support worker (who had been trained to deliver interventions) to implement the intervention for kinship carers in two nearby community venues. Both groups consisted of six carers. Of the twelve carers, ten had been involved in Step 4. The intervention was implemented over a five-week period, for two hours per week. At the end of each session, the research team obtained feedback from the family-support worker so as to consider any refinements to the intervention, and this prompted two rounds of focus groups with the kinship-carers. The first was conducted in November 2015 at the end of the final session of the intervention, and this gave rise to some additional refinements to the intervention. The second was held in February 2016 in order to explore two matters: first to find out whether the kinship carers had applied what they had learnt from the intervention, especially over the Christmas period which is often a difficult time for families; and second, to seek their responses to the refinements to the intervention.

The kinship carers' immediate responses to the intervention in November 2015 were positive. All commented on the usefulness of the behaviour control and conflict management content. As a result of the intervention, they had been given the time and skills to reflect on the influence of their own role in their relationship with their teenager. All reported better connectedness with their teenager, as illustrated by Brenda’s comments below:

I’m usually really quite highly strung. I’m a bit of a control freak as well, to be honest. I like things to be done the way I want them to be done, and of course teenagers don’t work like that, but I’ve noticed now that I’ve been calm and saying, ‘Look, I know it’s not fair, but this is what we have to do, blah, blah'. A month ago it would have just been ‘Get out my room, get out my room, get out my room'. And that’s how we were communicating… Yeah, now instead I’m even just throwing him a wee, ‘How did you get on today then?’, rather than ‘Shut your face, turn that music down!’ […] Before he’d come into the kitchen and his music’s blaring and the first thing I would have said is ‘Turn that down, can’t hear the telly!!’, like that’s the most important thing in the world. But he was singing and I started singing too, doing all the harmonies, so it was really nice.

Rosie had learned how to take time to listen to her teenage grandson:

And I would never have thought of asking him first to think about what he wanted to tell me, because the washing machine’s going, the cooker’s on, kettle’s on. Your mind’s always elsewhere eh? But you tell him to go and think about what he wants to say to you first so he’s got the story straight…and then get a coffee, tea, hot chocolate, whatever…And then he knows you’re completely listening. And he’s happy with that, he knows you’ve listened to him. I’ve never heard him say to me all week, ‘are you listening to me?’

Melanie, too, seemed to have become more aware that she, as the adult, should be responsible for leading the tone of their interaction:

I need to remember that I am the actual adult, and I know if I kick off, it just goes on, it’s like the…what do they call it? Aye, the ripple effect, I kick off, he kicks off, the wee man kicks off, and we’re all…and it’s not been like that this week. I think my neighbours must think I’m away on holiday.

In short, carers appeared to approach each interaction more calmly and openly, to listen more effectively, to speak more clearly, explaining actions rather than seeking to impose them, thereby transforming their relationship with their teenager.

There is a further consideration. In the present study, as stated, all of the carers were grandparents (all but one grandmothers), most of whom had chronic medical conditions. They had initially reported feelings of stress, but, as a result of the intervention, had begun to deal with it. The core message from the PLAY techniques was about ‘taking time to care for yourself in order to care better for others', as Jackie had done:

Before I did this, I had six jobs in my head at once, right, and another six planned for after it, and then the next six. Your brain was too busy all the time, and now I feel I am getting a bit of breathing space, and there’s times when I’m thinking, no, I’m not doing nothing, I am sitting having my coffee, whereas I would never have done that before.

Of the specific techniques taught, balancing and breathing were typically reported to be the most useful, as illustrated by Sharon’s comment:

Because while you’re concentrating on that [the balance], your mind sort of goes blank, if you like, so you’re not thinking about, oh god, steak pie for tea, right, I’ll do this or that, you’re just concentrating on your balancing, and then last week I realised, actually, I feel quite relaxed!

And, similarly, Margaret:

I totally agree with it, that that relaxation bit and that breathing bit […] I never used to eat during the day. […] I went all day with nothing, I put that child first. Everybody used to say, 'You’re his maid.' And since I’ve been coming here, I am not, I’m thinking of me. I’m breathing, I’m making time to eat, I’m making time to sit down and take my tablets. Just take the time to do the breathing, because if I’m not well enough myself, then how can I possibly be doing right by that child? I’m going to take care of myself, but it’s one of the hardest things to do is pay attention to yourself because your focus is that child.

A number of suggested changes to the delivery of the intervention were identified during the November 2015 focus groups. It was suggested that during Week 1, the intervention be more clearly outlined so that carers would know exactly what content to expect. Carers also reported that they would have preferred the order of content to focus first upon teenager-related learning, followed by content related to their own wellbeing (that is, the PLAY techniques). For all sessions, a cake-and-coffee break was asked for.

The second round of focus groups, held in February 2016, enabled the participants to report what effects, if any, the intervention had made to their lives as kinship carers during the intervening ten-week period. Their responses centred on four themes: the PLAY techniques relating to breathing and their perceived effect on the relationship with their teenager; impact upon self-awareness and communication; behaviour control; and approval of intervention refinements.

First, in response to the question of what they felt had been the most useful aspects of the intervention, they immediately and unanimously stated that it had been the ‘breathing’ technique. They had used it in a variety of settings. For example, in meetings with teachers at school:

Fiona: I’m a lot calmer dealing with them. I do my breathing exercises before I have to go to meetings about their behaviour at school, and during the meetings too.

Or before having a ‘difficult’ conversation with their teenager:

Margaret: When the kids are arguing all the time I do the breathing to calm myself doon and just ignore them – they dinny listen if I shout, so I just count to ten and breathe.

Similarly, they also reported teaching the breathing techniques to their teenagers so as to help them manage their own feelings of tension.

The second emergent theme was the reported impact on the kinship carer's self-awareness when communicating with their teenager. For Sharon this meant allowing her teenager to approach her on his terms, rather than relentlessly asking him what the matter was when it was clear he wasn’t in a good mood. She found that, when she allowed him to do this, both the quality of the communication and the outcome of the conversation were greatly improved. This awareness-enhancement was also linked to managing conflict with him. The carers discussed how they now attempt to manoeuvre any important and/or difficult conversation with the teenager so that it occurs in an environment that is more conducive to talking. For some, that was being in the same room and not shouting from one room to another; for others, it was sitting side by side, in the car, or in the dark before bedtime, in order that the conversation felt less confrontational and more relaxed. This is illustrated in Elizabeth’s excerpt below.

Elizabeth: If he comes through the door and I know there’s something wrong I’m leaving it till he’s ready to come to me, rather than me going to him going ‘what’s wrong wi’ you now?’. Instead I just wait till he’s ready to come and see me.

I: Has that changed the quality of your relationship?

Elizabeth: Yeh, ‘cos he’ll come and tell you more when he’s ready, whereas before I’d be ‘What’s wrong?’ and he’d be ‘Nothing’; and you know something is wrong, ken, just wi’ the way he comes in, ken, in a mood, ken, slammin’ the front door an’ that. You ken there’s definitely something wrong, but now I just let him go to his room and when he’s ready he’ll come and talk about it.

The third theme was the effect on behaviour control. The carers reported a greater awareness of their role in the relationship, and of the impact of that upon behaviour. For example, they found that if they spent more time calmly explaining the rationale for behavioural rules, then these were more likely to be adhered to, and there was less likelihood of a conflict escalating. Finally, the fourth emergent theme was that the carers regarded as useful the refinements made as a result of the first round of post-intervention focus groups, and suggested that the intervention would also prove beneficial for other groups.

Conclusion

This paper has described the development of an intervention programme to support kinship carers of teenage children in Scotland (CARE). It was based on the 6SQuID framework, an innovative, collaborative and co-produced pragmatic framework for designing, implementing and evaluating an intervention across a range of public policy endeavours. It began by bringing to the fore the perceived needs of the target group, kinship carers. The CARE intervention programme was pilot-tested and adapted in two settings, and this will inform a subsequent and fuller evaluation of the CARE programme. That is to say, the intention hereafter is to proceed to Step 6 of the 6SQuID framework, namely to ‘Collect sufficient evidence of effectiveness to proceed to a rigorous evaluation’. This work has yet to be completed. At this stage, appropriate caution is warranted when interpreting the findings, for a number of reasons. The sample was relatively small, and those who comprised it were not randomly drawn; the kinship carers in this study were used to being together in their weekly kinship care support groups. The programme may have been developed, received and refined differently if these kinship carers had not had an existing relationship with each other. Only one carer was male, and a study with an equal gender-balance may have yielded different results. For reasons given, the study omitted the cared-for teenagers themselves. The study was based in Scotland, and cross-national inferences from the findings warrant caution (Hank and Buber, 2009).

The study has yielded two sets of benefit. The first is methodological. The development of the CARE intervention programme reported here suggests strongly that the 6SQuID opens up useful methodological procedures which can be applied in a range of public health and social work settings. In this study, the resulting intervention has drawn on the evidence of effective parenting interventions for teenagers; it targeted only kinship carers of teenagers; it was co-produced with kinship carers; it focused on the wellbeing of the carer; and it was developed specifically for use in the context in which it was implemented, but with scope for modification and expansion to other parenting groups. The rich qualitative data reported here gives a sense of the lived multiple adversities which kinship carers, particularly grandparents, constantly confront. The ‘carer strain' – to use Farmer's (2009: 339) apt phrase – was revealed also in this study, as it was also in Australian studies (Dunne and Kettler, 2008; Orb and Davey, 2005), in Houston et al.'s (2017) Irish study of carers of mainly teenagers, and in Leder et al.'s (2007) study in the United States. Unlike most of these studies, the research here has focused solely upon the kinship carers of teenagers.

Whilst some research has usefully highlighted the many difficulties and adversities faced by kinship carers, few studies have sought to address the means whereby the stress experienced by them can be mitigated in an accessible and practical manner. This study generated some ways forward, which, if they can be replicated more widely, may go some way in alleviating stress. In sum, a range of practical benefits emerged from this research: first, the PLAY breathing techniques had a reportedly positive stress-reduction effect on carers themselves, and in their dealings with their teenager(s); second, the study showed a reportedly increased carer self-awareness of their communication or ‘connectedness' with their teenager; and third, there was a stated positive impact upon behaviour control as a result of the stress-reduction and improved connectedness. These may be mutually reinforcing: the carers feel less stressed; the quality of their interactions with the teenagers improves; and behaviour control is enhanced.

The field of kinship care is under-researched, and because it resides in an ill-defined space between private and public provision, it does not have the organisational status and focus which is assigned to government-funded foster care. Finally, it is recognised that many kinship carers are from deprived, resource-poor areas. The kinship carers in this study were no exception. The concern here has been with some of the modifiable factors (we considered techniques to do with connectedness, behaviour control, and stress-reduction) which serve to improve the lives of kinship carer and teenager alike. Our approach has not addressed the adverse structural conditions which beset these families, and it is important not to de-contextualise or to de-politicise the carers' concerns, thereby giving them the impression that because they have been taught these skills they should neither need nor expect further support.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Audit Scotland. (2010) Getting it right for children in residential care. Available at: www.audit-scotland.gov.uk/docs/local/2010/nr_100902_children_residential_km.pdf (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Berridge D, Biehal N, Henry L. (2012) Living in children’s residential homes. Available at: http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/13956/1/DFE-RR201.pdf (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Citizens Advice Scotland (2016) Kinship care – The relative value. Available at: www.cas.org.uk/features/kinship-care-relative-value (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Cuddeback GS. (2004) Kinship family foster care: A methodological and substantive synthesis of research. Children and Youth Services Review 26(7): 623–639. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsbacka M, Tanskanen AO, Jokela M, et al. (2011) Grandparental child care in Europe: Evidence for preferential investment in more certain kin. Evolutionary Psychology 9(1). Available at: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/147470491100900102: 320–340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne EG, Kettler LJ. (2008) Grandparents raising grandchildren in Australia: Exploring psychological health and grandparents’ experience of providing kinship care. International Journal of Social Welfare 17(4): 333–345. [Google Scholar]

- Falkirk Council. (2016) Children and families: Fostering. Available at: www.falkirk.gov.uk/services/children-families/fostering/kinship-care.aspx (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Farmer E. (2009) How do placements in kinship care compare with those in non-kin foster care: Placement patterns, progress and outcomes? Child & Family Social Work 14(3): 331–342. [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia B. (2016) Looked-After Children Statistics: Analysis of Scottish Government Social Work Statistics, 2014–15 CELSIS. Available at: www.celcis.org/files/7214/6366/6197/CELCIS-new-analysis-Looked-after-children-statistics-April-2016.pdf (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Ford J, Scott E, Woodman K, et al. (2013) Outcomes Framework for Scotland’s National Parenting Strategy. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland.

- Hank K, Buber I. (2009) Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: Findings from the 2004 Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe. Journal of Family Issues 30(1): 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Houston S, Hayes D, MacDonald M. (2017) Hearing the voices of kinship foster carers in Northern Ireland: An inquiry into characteristics, needs and experiences.Families, Relationships and Societies. Epub ahead of print on July 18, 2016. doi: 10.1332/204674316X14676449115315. Available at: www.ingentaconnect.com/content/tpp/frs/pre-prints/content-PP_FRS-D-16-00017R2 [DOI]

- Leder S, Grinstead LN, Torres E. (2007). Grandparents raising grandchildren: Stressors, social support, and health outcomes. Journal of Family Nursing 13(3): 333–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markham CM, Lormand D, Gloppen KM, et al. (2010) Connectedness as a predictor of sexual and reproductive health outcomes for youth. Journal of Adolescent Health 46(3, Supplement): S23–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentor (2017) Kinship care guide for Scotland. Available at: http://mentoruk.org.uk/kinship-care-guide-for-scotland/ (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Orb A, Davey M. (2005) Grandparents parenting their grandchildren. Australasian Journal on Ageing 24(3): 162–168. [Google Scholar]

- Scott E, Ford J, Woodman K, et al. (2014) Use of public health science to inform Scotland’s National Parenting Strategy: An outcomes framework approach. The Lancet 384(Supplement 2): S69. [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Government (2009) The Looked After Children (Scotland) Regulations 2009. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government (2016) Policy – Looked after children: Kinship care. Available at: https://beta.gov.scot/policies/looked-after-children/kinship-care/ (accessed 20 September 2016).

- Stewart-Brown S. (2012) Peer-led parenting support programmes. British Medical Journal Available at: www.bmj.com/content/344/bmj.e1160.full \ 344: e1160 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tapsfield R, Collier F. (2005) The Cost of Foster Care: Investing in Our Children’s Future British Association for Adoption & Fostering. Available at: www.thefosteringnetwork.org.uk/sites/www.fostering.net/files/content/cofc-report.pdf (accessed 20 September 2017).

- Van der Kolk B. (2014) The Body Keeps the Score. New York: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Wight D, Wimbush E, Jepson R, et al. (2015) Six steps in quality intervention development (6SQuID). Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 70: 520–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]