Abstract

Educational attainment is increasingly associated with family inequality in the U.S., but there is little understanding about whether and how education stratifies attitudes toward eldercare. Using the General Social Survey 2012 Eldercare Module, I test the association between educational attainment and attitudes toward eldercare provisions of Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) including different combinations of help and payment for help. IADLs are the most common care received by older adults and needs are projected to grow, so understanding attitudes toward this type of care is timely and relevant. Results show that adults with a bachelor’s degree or graduate/professional degree, compared to adults with less than a high school degree, are more likely to support complete family IADL eldercare, where families provide the care and any payment necessary for care, compared to complete outside IADL eldercare, where outside institutions provide both care and payment. Educational attainment is an important axis of stratification in the U.S. and may explain potentially bifurcated policy solutions desired among different groups.

Keywords: Educational Attainment, Family Caregiving, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Government Support

Introduction

The aging U.S. population and their increasing need for care is an important policy issue for families, older Americans themselves, and public programs (Congressional Budget Office, 2013; Family Caregiver Alliance, n.d.). One of the most common care needs among older adults is help with Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADLs), which includes household maintenance, doing laundry, shopping, and traveling. One out of five adults ages 65 years and older currently needs help with IADLs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009), and these rates are expected to increase as the population ages (Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2011). Little is known, however, about American attitudes toward helping older adults meet their IADL needs and most policy studies view family and outside institutional responsibilities for eldercare as separate (Jamshidi, Oppenheimer, Lee, Lepar, & Espenshade, 1992). When given a choice, do Americans see IADL eldercare as a responsibility of families, outside institutions, or a combination responsibility of the two?

Studying attitudes can help understand perceptions of institutional responsibility (Pew Research Center, 2015; Stokes, 2013). Attitudes are also important because they have the potential to influence social policies (Henderson, Monroe, Garand, & Burts, 1995) and access to long term care for older adults (Albertini & Pavolini, 2017). Additionally, attitudes may reflect planned behavior, with positive attitudes toward family eldercare mirroring actual caregiving (Silverstein, 2006). Given overarching “family as caregiver” norms in the U.S. (Folbre, 2002; Marcum & Treas, 2013; Montgomery, 1999), there is reason to believe that Americans will strongly and universally value complete family IADL eldercare over any provisions from outside institutions.

Currently, there is no study, to my knowledge, that examines educational attainment’s association with attitudes toward provisions of IADL care for older adults. It is especially important to understand this association because educational attainment is a main axis of socioeconomic class in the U.S. (Hout, 2012) and a social status increasingly linked to inequalities among families (Cherlin, 2014) and ageing and well-being (Margolis, 2013). Using the 2012 Eldercare Module in the General Social Survey, I test whether there are educational attainment differences in attitudes toward combinations of IADL eldercare and payment for care between families and outside institutions. I control for a series of important demographics, family characteristics, and other attitudes. This study contributes to the literature in three ways: by focusing specifically on the most common form of care needed among older adults (i.e. IADLs); by testing whether Americans see IADL eldercare provisions as a responsibility for families, outside institutions, or a combination; and, by testing whether and how educational attainment stratifies attitudes toward provisions of eldercare. Stratification of attitudes may signal ways in which care needs among older American may become increasingly unequal.

Background

Assistance with IADL tasks are the most common form of care needed across the life course, but especially among older adults (Adams & Martinez, 2016), and receiving help with these tasks allows individuals to maintain independent living. Families providing caregiving that keeps older adults in the community is worth an estimated 1.4 billion dollars per year, according to 2002 estimates (Rhee, Degenholtz, Lo Sasso, & Emanuel, 2009). Although IADLs are in contrast to more intense forms of care needs known as Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) (e.g. help with bathing and getting dressed), often older adults who need help with ADLs are more likely to be institutionalized (Gaugler, Duval, Anderson, & Kane, 2007). Therefore, focusing on help needed with IADLs captures a larger group of older adults in the population and has the potential to positively affect older adults, families, and public spending by keeping older adults in the community and out of institutions.

Who is responsible and for what?

In the U.S., caregiving is generally seen as a “private trouble” that older adults and families should take care of and not as a “public issue” where outside institutions are responsible for meeting needs (Mills, 1959; Pavalko, 2011). This divide is illustrated by the U.S.’s liberal welfare state, with few state interventions that aid families (Esping-Andersen, 1990; Marcum & Treas, 2013), and empirical trends that show families provide most of the help needed by older members (Spillman, Wolff, Freedman, & Kasper, 2014). However, families may feel as if they have no choice but to provide care (Glenn, 2010) and thusly feel a “caregiving squeeze” because of limitations on time and resources available to do so (Pavalko, 2011). Additionally, changes in family structures among older adults, like increasing rates of kinlessness (Margolis & Verdery, 2017) and rising rates of grey divorce (Brown & Lin, 2012), may leave more older adults in need of non-family social support (Silverstein & Giarrusso, 2010).

The line between eldercare as a “private trouble” or “pubic issue” is not so clear cut, with families and outside institutions often working in combination to provide personal care and financial resources for older family members in different ways. For instance, older adults often rely on “care convoys” where they receive help from family members even when institutionalized (Kemp et al., 2018), or families may pay other family members or private providers for care help with older members (Whitlatch & Feinberg, 2006). Although some older adults completely rely on family or others on outside institutions, like the government or private providers, partnerships between the two may better help meet growing needs among an aging population. For instance, as states increase spending on home and community based services for older adults, fewer older adults rely on more costly state-run institutionalization (Burr, Mutchler, & Warren, 2005), which in turn can reduce spending by Medicaid (Barczyk & Kredler, 2018). Receiving more care, by family members or paid outside caregivers, is associated with positive benefits for the older adults themselves, including being less likely to be “homebound” and isolated from the community (Reckrey, Federman, Bollens-Lund, Morrison, & Ornstein, 2019).

Whether Americans’ see caregiving for older adults as an either/or issue is currently unclear as few studies in the U.S. gauge attitudes toward combinations of provisions (Jamshidi et al., 1992) and instead usually measure either family or outside institutional supports. For instance, one set of scholarship focuses on attitudes toward programming or funding of large government health or income programs, like Social Security (Silverstein, Angelelli, & Parrott, 2001; Silverstein & Parrott, 1997; Yang & Barrett, 2006). These programs are often viewed separately from direct family caregiving, like norms of filial obligation or co-residence (Alwin, 1996; Brody, Johnsen, & Fulcomer, 1984). One U.S. study does test attitudes toward different policy solutions for family caregivers of an ill or disabled member. Silverstein and Parrott (2001) find that adults with higher levels of education are more likely to support time off work without pay for family caregivers and are less likely to support tax credits or directly paying caregivers. These results support further investigating potential socioeconomic class divisions in attitudes toward combinations of eldercare provisions by families and outside institutions in the U.S.

Education and eldercare attitudes

Educational attainment is increasingly a marker of socioeconomic status in the U.S. (Hout, 2012) and often stratifies other social attitudes (Campbell & Horowitz, 2016; Kalmijn & Kraaykamp, 2007), though the direction of the association is mixed. On one hand, some work finds that education may reinforce dominate cultural ideologies (Jackman & Muha, 1984; Phelan, Link, Stueve, & Moore, 1995; Schnabel, 2018), such as stronger support of traditional family norms (Cherlin, 2014; Thornton, Alwin, & Camburn, 1983). This framework for educational effects may explain why, in a liberal welfare state like the U.S., higher educational attainment is associated with less support for large government programs (Morin & Neidorf, 2007; Silverstein & Parrott, 1997; Yang & Barrett, 2006), though some studies find no difference in support (Marcum & Treas, 2013; Silverstein & Parrott, 2001). On the other hand, education may be associated with liberalizing attitudes toward families. There is support for this framework including a liberalizing effect on various definitions of family (Powell, Bolzendahl, Geist, & Steelman, 2010) and greater acceptance of egalitarian roles for women (Kane, 1995; Thornton et al., 1983). This liberalizing effect may not translate to care norms, however, as Americans widely agree that adult children should care for their aging parents (Finley, Roberts, & Banahan, 1988; Ganong & Coleman, 1998).

It is unclear whether and how education may be associated with eldercare attitudes specifically because current knowledge about attitudes toward family or outside institutionalized care tends to focus on children only (Hays, 1998; Powell et al., 2010). This work finds that educational attainment is associated with “neotraditional” family culture, or an increased sense of family obligation for childcare (Cherlin, 2014: 144). However, it is difficult to draw direct lines between these findings and eldercare attitudes because public support for children and older adults are often quite different (Preston, 1984) and within the U.S., older adult programs generally receive more public support than children’s programs (Marcum & Treas, 2013).

Methods

The 2012 General Social Survey (GSS) is a nationally representative survey of U.S. adults. The Eldercare Module was only fielded in 2012 and is the best source of nationally representative data available regarding attitudes toward IADL help for older adults. The module was given to a random sample within the GSS, ages 18 to a cap of 89+ (determined by GSS) (N=1,302). Pre-testing on these eldercare items showed reliable measurement (Scholz, Jutz, Edlund, Oun, & Braun, 2014). The two items used to create the dependent variables have significant missingness (11.2% for help; 19.4% for payment); however, almost all missing on both items is due to respondents answering “Don’t Know” (only 6 cases within each are “no answer”). Additional analyses on these “Don’t Knows” are discussed in the sensitivity analysis, but do not change the substantive arguments of this paper. Education has no missingness and control variables have low levels of missingness with the highest missingness on income (10.5%). Due to missingness on the dependent variable I use the “multiple imputation then deletion” method (von Hippel, 2007). I use Stata 15.1 to run multiple imputation with chained equations (m=25). The final analytic sample is 933 American adults ages 18 and older.

Measures

The dependent variable measures whether Americans think that families or outside institutions should help older adults with IADLs and pay for the help. This variable is created from two measures within the Eldercare Module. Regarding care, the first question asks: “thinking about elderly people who need some help in their everyday lives, such as help with grocery shopping, cleaning the house, doing laundry, who do you think should primarily provide this help?” The current focus of the study is on whether respondents see this type of help as one for families or other outside institutions; therefore, institutions are dichotomized: family versus outside institutions (i.e. government, non-profits, private providers). The second item is a follow-up question to the first and inquiries about respondents’ attitudes toward who should pay for this care. It asks: “And who do you think should primarily cover the costs of this help to these elderly people?” GSS limited the choices for this item to only two choices: older adults themselves/their family or the government/public. I combine these two measures to create four mutually exclusive categorizations around IADL eldercare attitudes: complete family IADL eldercare (family provide both care and payment), outside-funded family IADL eldercare, family-funded outside IADL eldercare, and complete outside IADL eldercare (outside institutions provide both care and payment).

The key independent variable is educational degree attainment, coded by the GSS: less than high school, high school, junior college, bachelor’s, and graduate degree. Additional analyses with years of education and a dichotomous measure for college degree showed similar results. I control for other important demographic, family, attitudinal, and caregiving characteristics associated with eldercare behavior or other family attitudes (Alwin, 1996; Mair, Chen, Liu, & Brauer, 2016; Marcum & Treas, 2013; Thornton, 1989). Age ranges from 18 to a cap imposed by GSS of 89+. Gender is coded female. Race and ethnicity are two separate questions in the GSS and are combined to make four mutually exclusive categories: White, non-Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; Other, non-Hispanic. Marital status is dichotomized: married or not married (divorced, separated, widowed, and never married). Number of siblings and children are categorized: none, one to three, four or more. Current caregiving is coded yes or no if respondents provide any response to: “On average, how many hours a week do you spend looking after family members (e.g. children, elderly, ill or disabled family members)?” Employment status is coded as working (full-time and part-time), or not (temporarily not working, unemployed, retired, students, keeping house, “other”). Family income is logged in the models and treated as continuous. Political party affiliation is coded as a three-category variable: republican, independent/other, and democrat. Respondent attitudes toward current government spending on Social Security is categorical: too much, about right, too little. Respondent agreement with norms of filial obligation is dichotomous. Similar to Alwin (1996), I approximate respondents’ proximity to their parents based on their residential mobility since age 16: living in the same city, same state/different city, or different state as when they were 16.

Analytic Plan

First, descriptive statistics give an overview of the sample and distribution of the main attitude measure (Table 1). Second, a descriptive figure presents differences by educational attainment (Figure 1). Third, I estimate a multinomial logistic regression model for whether Americans think families or outside institutions are responsible for provisions of care for older adults, controlling for important characteristics (Table 2). Poststratification weights are used to make estimates nationally representative of the U.S. adult population (General Social Survey, 2018).

Table 1.

Weighted Descriptive Statistics

| Mean or Percentage | |

|---|---|

| Help and Payment for Older Adults’ IADLs | |

| Complete Family IADL Eldercare | 47.4% |

| Outside-Funded Family IADL Eldercare | 21.3% |

| Family-Funded Outside IADL Eldercare | 6.6% |

| Complete Outside IADL Eldercare | 24.6% |

| Educational Degree Obtained | |

| Less than High School Degree | 14.2% |

| High School Diploma or GED | 52.6% |

| Junior College | 7.8% |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 16.7% |

| Graduate or Professional Degree | 8.6% |

| Control Variables | |

| Age | 44.7 |

| Female | 50.3% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 62.8% |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 14.6% |

| Hispanic | 16.2% |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 6.4% |

| Married | 51.9% |

| Number of Siblings | |

| None | 4.9% |

| 1 to 3 | 59.5% |

| 4 or more | 35.6% |

| Number of Children | |

| None | 30.0% |

| 1 to 3 | 56.7% |

| 4 or more | 13.3% |

| Currently Caregiving | 63.0% |

| Employed | 63.7% |

| Family Income | $39,272 |

| Political Party Affiliation | |

| Democrat | 33.1% |

| Independent | 42.0% |

| Republican | 24.9% |

| Current Government Spending on Social Security | |

| Too Much | 9.0% |

| About Right | 34.0% |

| Too Little | 56.9% |

| Agree with Filial Obligation | 86.8% |

| Residential Mobility Since Age 16 | |

| Same City | 40.8% |

| Same State, Different City | 23.4% |

| Different State | 35.8% |

Data: 2012 General Social Survey, N=993 (M=25)

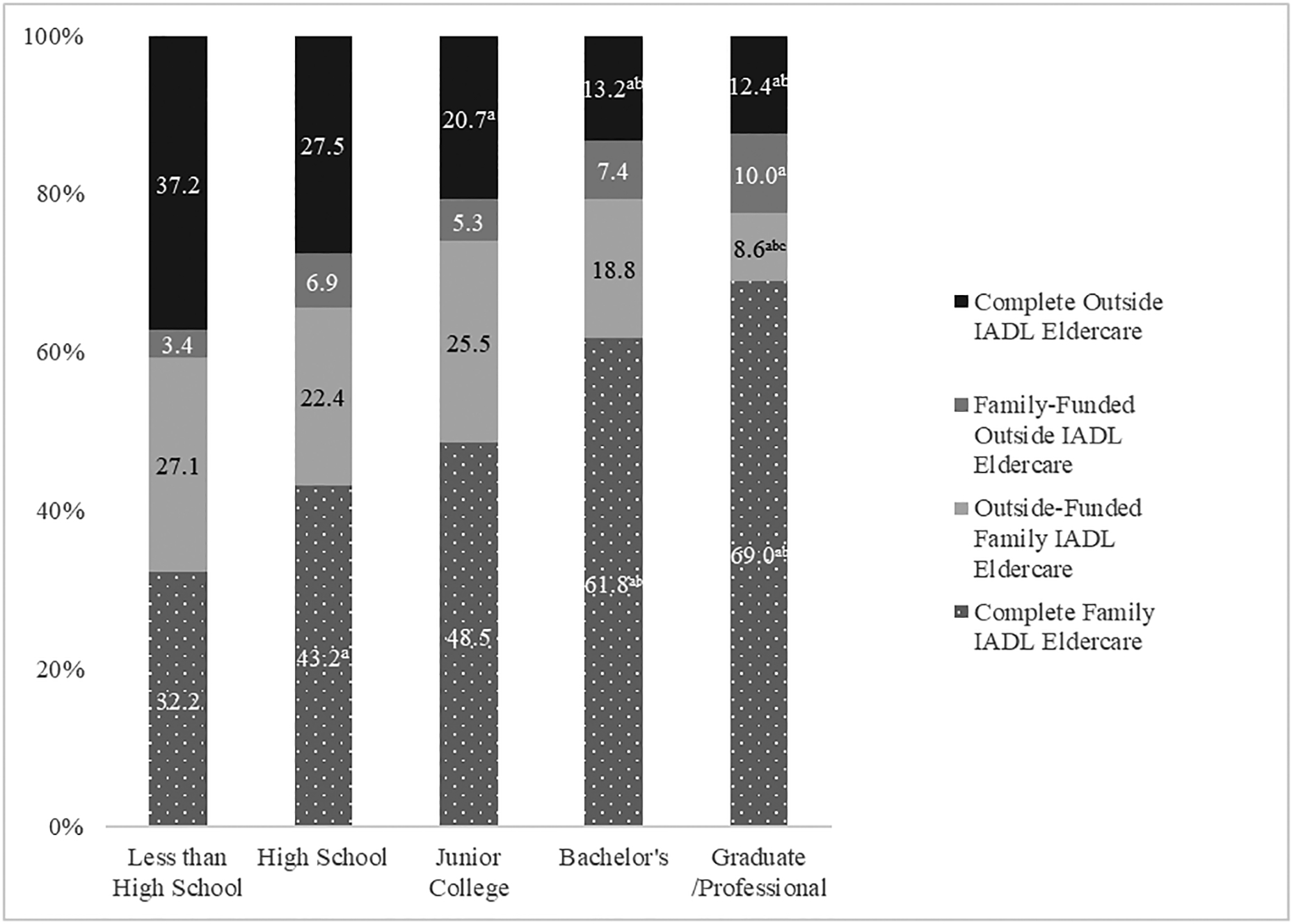

Figure 1.

Percent of U.S. Adults Supporting Family or Outside IADL Care Provisions for Older Adults, by Educational Attainment

Notes: General Social Survey 2012, N=933 (M=25), Weighted

a= Significantly different from Less than High School (p<.05)

b= Significantly different from High School (p<.05)

c= Significantly different from Junior College (p<.05)

Table 2.

Weighted Relative Risk Ratios for Which Institution Should Provide IADL Provisions for Older Adults, Compared to Complete Family IADL Eldercare

| Outside-Funded Family IADL Eldercare | Family-Funded Outside IADL Eldercare | Complete Outside IADL Eldercare | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational Degree (Less than high school omitted) | |||

| High School | 0.647 | 1.466 | 0.635 |

| (0.219) | (0.769) | (0.199) | |

| Junior College | 0.981 | 1.254 | 0.569 |

| (0.497) | (0.928) | (0.270) | |

| Bachelor’s | 0.583 | 1.100 | 0.295** |

| (0.264) | (0.759) | (0.120) | |

| Graduate/Professional | 0.314* | 1.297 | 0.231** |

| (0.176) | (0.849) | (0.116) | |

| Control Variables | |||

| Age | 0.988 | 0.990 | 0.999 |

| (0.008) | (0.010) | (0.007) | |

| Female | 0.901 | 0.806 | 1.183 |

| (0.209) | (0.232) | (0.245) | |

| Race (White, Non-Hispanic omitted) | |||

| Black | 2.166* | 1.618 | 3.206*** |

| (0.761) | (0.816) | (0.993) | |

| Hispanic | 1.291 | 0.726 | 1.145 |

| (0.442) | (0.381) | (0.346) | |

| Other | 0.928 | 0.270 | 1.523 |

| (0.589) | (0.217) | (0.748) | |

| Married | 0.690 | 0.658 | 0.870 |

| (0.172) | (0.219) | (0.192) | |

| Siblings (no siblings omitted) | |||

| 1 to 3 | 0.749 | 12.602* | 1.126 |

| (0.365) | (13.760) | (0.550) | |

| 4 or More | 1.028 | 12.605* | 1.416 |

| (0.512) | (14.136) | (0.711) | |

| Children (no children omitted) | |||

| 1 to 3 | 0.793 | 1.033 | 0.807 |

| (0.251) | (0.401) | (0.224) | |

| 4 or More | 0.676 | 0.614 | 0.701 |

| (0.275) | (0.346) | (0.284) | |

| Currently Caregiving | 1.036 | 0.829 | 1.360 |

| (0.270) | (0.302) | (0.337) | |

| Employed | 0.885 | 0.700 | 0.848 |

| (0.234) | (0.226) | (0.195) | |

| Logged Family Income | 0.731* | 1.178 | 0.830 |

| (0.095) | (0.401) | (0.105) | |

| Political Party Affiliation (Democrat omitted) | |||

| Independent | 0.895 | 1.150 | 0.572* |

| (0.241) | (0.381) | (0.138) | |

| Republican | 0.618 | 0.915 | 0.307*** |

| (0.214) | (0.349) | (0.094) | |

| Current Government Spending on Social Security (too much omitted) | |||

| About Right | 3.395** | 1.415 | 3.436* |

| (1.570) | (0.724) | (1.823) | |

| Too Little | 4.818*** | 1.231 | 5.868** |

| (2.150) | (0.645) | (3.022) | |

| Agree with Filial Obligation | 1.190 | 0.536 | 0.811 |

| (0.411) | (0.213) | (0.224) | |

| Residential Mobility Since Age 16 (different state omitted) | |||

| Same State, Different City | 1.387 | 0.621 | 0.850 |

| (0.431) | (0.218) | (0.226) | |

| Same City | 1.588 | 0.804 | 0.984 |

| (0.469) | (0.287) | (0.228) | |

| Constant | 8.877 | 0.009* | 2.105 |

| (13.274) | (0.020) | (3.181) | |

Notes: 2012 General Social Survey, N=933 (M=25), Standard Errors in Parentheses,

p<0.001,

p<0.01,

p<0.05

Results

First, I present weighted descriptive statistics for American adults in my sample (Table 1). I briefly describe the main variables of interest here. Overall, almost half of U.S. adults (47.4%) support complete family IADL eldercare, or families providing both help and any payment associated with the help. Another quarter (24.6%) of adults support complete outside IADL eldercare, where outside institutions provide both help and payment. A little over one-fifth (21.3%) of adult support outside-funded family IADL eldercare, which could potentially include tax credits or other publicly funded help. Family-funded outside IADL eldercare, or families directly paying outside institutions like private providers or non-profits to help older adults, received the smallest amount of support (6.6%). The highest degree obtained for a majority of the sample is a high school diploma (52.6%), followed by a bachelor’s degree (16.7%), less than a high school degree (14.2%), a graduate/professional degree (8.6%), and junior college (7.8%).

Figure 1 presents the percentage of respondents in each education group supporting different combinations of care and payment. I find a significant relationship between educational attainment and eldercare attitudes (F-test, p<.05). As the figure illustrates, adults with a bachelor’s degree or more are almost twice as likely as adults with less than a high school degree to support complete family IADL eldercare (p<.05). The inverse relationship is true for complete outside IADL eldercare; adults with less than a high school degree are almost three times more likely than adults with a bachelor’s or graduate/professional degree to support complete outside IADL eldercare (p<.05).

Although a majority of respondents within each education group supports complete outside or complete family IADL eldercare, a proportion of respondents support combinations of care. This percentage ranges from 18.6% of adults with a graduate or professional degree to 30.5% of adults with less than a high school degree supporting some combination of provisions. Family-funded outside IADL eldercare is the least supported among all educational groups, except among the graduate/professional group. Outside-funded family IADL eldercare is more broadly supported across groups and at greater rates among adults with lower levels of educational attainment. For instance, 27.1% of adults with less than a high school degree support outside-funded family IADL eldercare compared to 17.6% of adults with a bachelor’s.

Table 2 presents weighted relative risk ratios from multinomial logistic regression models for eldercare provisions, controlling for covariates. All comparisons presented in the model are in relation to supporting complete family IADL eldercare. The main educational attainment differences are between complete family IADL eldercare and complete outside IADL eldercare. Having a bachelor’s or a graduate/professional degree is associated with a 72.0% (eβ = 0.280, p<.01) and 78.8% (eβ = 0.212, p<.01) decrease, respectively, in supporting complete outside IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare, holding other variables constant. There is no significant educational difference in attitudes when comparing complete family IADL eldercare to family-funded outside IADL eldercare. However, adults with graduate or professional degrees, compared to adults with less than a high school degree, are 70.0% less likely to support outside-funded family IADL eldercare compared to complete family IADL eldercare (eβ = 0.300, p<.05).

I control for a number of characteristics associated with educational attainment and attitudes, including demographic and family characteristics, but the main association could not be fully explained by these important covariates. Other covariates that are significantly associated with eldercare provision attitudes include race, number of siblings, income, political party affiliation, and attitudes toward current government spending on Social Security. Black adults, compared to White adults, are more likely to support complete outside IADL eldercare (p<.001) over complete family IADL eldercare. Adults with 1 to 3 or 4-or-more siblings are more likely to support family-funded outside IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare (p<.05). Higher income is associated with a reduction in risk of supporting outside-funded family IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare (p<.001). Independents and republicans, compared to democrats, are less likely to support complete outside IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare (p<.05; p<.001). Adults who think current Social Security funding is about right or too little have higher relative risk of supporting outside-funded family IADL eldercare and complete outside IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare (p<.05; p<.001).

Sensitivity Analysis

A large proportion of missingness in the original sample is due to respondents answering “Don’t Know.” Preliminary analyses on each of the two items used to create the main dependent variable here show that higher levels of educational attainment, compared to less than high school degree attainment, continues to be associated with more support for family eldercare or funding over other types of care. These results suggest that the main analyses presented here are not altered by the removal of the “Don’t Know” category.

Additional sensitivity analyses test variations in coding, additional variables, and a listwise deletion sample. By categorizing respondents into life course stages (i.e. 18 to 34, 35 to 54, 55 to 74, and 75+), the only significant age difference to emerge was that older adults, ages 75+, are significantly less supportive of outside-funded family IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare compared to younger adults ages 18 to 34 (p<.05) and adults ages 35 to 54 are significantly less supportive of family-funded outside IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare compared to young adults, ages 18 to 34 (p<.05). Quartile income categories among respondents showed a similar relationship for this comparison, whereby those with the highest income, compared to those with the lowest, were less likely to support outside-funded family IADL eldercare compared to complete family IADL eldercare (p<.01). Having a co-residential parent may alter eldercare attitudes but only a small proportion (<4%) of the sample was currently living with a parent, and models with this control were unstable. Results using a listwise deletion sample were similar to models presented here.

Discussion

IADL care needs among older adults are expected to grow as the population ages (Knickman & Snell, 2002; Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2011), but most policy research focuses on income and healthcare programs, to the neglect of everyday care policies (Myles, 2002). Further, few studies test attitudes toward different combinations of family and outside provisions of care (Jamshidi et al., 1992) and no study, to my knowledge, has directly measured attitudes toward help with IADLs in the U.S. specifically. In addition, little is known about education’s association with eldercare attitudes despite growing social stratification by education in the U.S. (Hout, 2012). Thusly, my study contributes to the literature by piecing together and building upon previous work to understand educational stratification of American attitudes toward institutional responsibility for the provision of IADL care for older adults.

Descriptive results show that the largest proportion of respondents support complete family IADL eldercare (47.4%), but over a quarter of the sample (27.9%) see eldercare as potentially a combination responsibility between families and outside institutions. Among the two combination possibilities, more respondents support outside-funded family IADL eldercare, which could include programs like waivers or tax credits for caregivers, over family-funded outside IADL eldercare, which may include families paying for private providers or non-profits to directly care for older adults. The remaining quarter of the sample support complete outside IADL eldercare (24.6%). While almost half of respondents feel that the family should provide both help and any payment associated with helping, the other half of respondents see outside institutions, like the government or private providers, as resources for helping meet IADL needs of older adults. These findings align with the reality of caregiving in the U.S. For instance, even though some policies provide some aid for older adults and their families, for example through waivers that fund caregiver support services (Feinberg, Wolkwitz, & Goldstein, 2006) current policies often do not cover most caregiver needs (Eifert, Adams, Morrison, & Strack, 2016) and families may not be able to afford some of the associated costs (Bookman & Kimbrel, 2011; Wolff, Spillman, Freedman, & Kasper, 2016). Thusly, some care may go unaddressed when outside supports are not available (Kane et al., 2013). As the aging population’s needs increase this issue will grow in importance for older adults, their families, and the social safety net.

Results show a clear relationship between educational attainment and attitudes toward provisions of IADL care for older adults. Adults with a bachelor’s degree or graduate/professional degree, compared to adults with less than a high school degree, have higher relative risk of supporting complete family IADL eldercare compared to complete outside IADL eldercare. Adults with a graduate/professional degree, compared to adults with less than high school degree, also have lower relative risk of supporting outside-funded family IADL eldercare over complete family IADL eldercare. These results suggest that educational attainment may reinforce the dominant cultural narrative (Jackman & Muha, 1984; Phelan et al., 1995; Schnabel, 2018), which in the U.S. would be a “family as caregiver” ideology. These results also align with recent family demography scholarship that suggests an association between higher educational attainment and “neotraditional” family ideology in the U.S. (Cherlin, 2014). In addition, considering the cultural narrative of the liberal welfare state, my findings align with other scholarship that finds higher education is generally associated with lower support for redistribution policies, government aid (Blekesaune, Quadagno, & Blekesaune, 2003; Esping-Andersen, 1990; Jacoby, 1994; Morin & Neidorf, 2007; Svallfors, 1997), and direct financial support to family caregivers (Silverstein & Parrott, 2001).

Because higher educational attainment is associated with higher income in the U.S. (Ryan & Bauman, 2016) and better health outcomes for older adults (Margolis, 2013), an alternative explanation for these findings may be that respondents with more education feel more secure in the ability to care for older family members due to family member health and resources. Therefore, educational attainment may not only be measuring ideology but also be measuring a sense of security among highly educated respondents. However, income has mixed results in my models, and I could not control for the health of family members. Family income was significantly associated with lower relative risk of supporting outside-funded family IADL eldercare compared to complete family IADL eldercare. Although the coefficient for income suggests lower support for complete outside IADL eldercare, compared to complete family IADL eldercare, the association was not significant. These results suggest income may be associated with particular redistribution or policy attitudes but not others (Fong, 2001; Silverstein & Parrott, 2001). The GSS items are worded such that asking who “should” provide the help better captures general attitudes about intergenerational beliefs compared to items that ask the respondent directly what they would do (Ganong & Coleman, 2005). Given that education is increasingly associated with other attitudes towards families (Cherlin, 2014; Powell et al., 2010) in addition to divergent sociopolitical attitudes (Campbell & Horowitz, 2016; Phelan et al., 1995), the result with income further support the theoretical stance that education is likely transmitting the dominant culture narrative rather than attitudes being dictated by available resources. Future work should continue to understand the complex ways in which education and other resources shape attitudes and behavior.

These results matter because if highly educated adults are more likely to endorse complete family care, outcomes for older adults in the U.S. may become increasingly unequal as the nation becomes better educated. Recent scholarship in Europe shows that stronger national level endorsements of a “family as caregiver” ideology are associated with more unequal access to long-term care options for older adults (Albertini & Pavolini, 2017). This is an important issue because current social policies in the U.S. are not keeping pace with changing families and caregiving needs (Brody et al., 1984; Family Caregiver Alliance, n.d.) and Americans may desire and endorse different policy solutions along socioeconomic class lines (Henly, Shaefer, & Waxman, 2006; Silverstein & Parrott, 2001). Although popular policy solutions like paid leave can be helpful for caregivers (Family Caregiver Alliance, n.d.; Koerin, Harrigan, & Secret, 2008), adults with lower levels of education are the least likely to have access to these types of policies (Glynn, Boushey, & Berg, 2016). Given that even institutionalized older adults still receive family care (Kemp et al., 2018), concerns that providing outside help, like paid formal care or resources, will “push out” informal caregivers or discourage family members from caring is unfounded (Hanley, Wiener, & Harris, 1991; Li, 2005). As the population ages and eldercare needs increase, a disconnect between attitudes and the levels of support provided may put increasing pressure on families and thusly reinforce social inequalities.

Limitations

The GSS is the only nationally representative dataset that offers these IADL eldercare questions about both care and payment for care with options of families or outside institutions; however, there are limitations to the findings. Although IADLs are the most common form of care received by older adults, the current study cannot distinguish between care provision attitudes about more intense forms of care (e.g. help with ADLs). Future research should gauge attitudes toward who should provide provisions as the intensity of care changes. Future research should also investigate “who” exactly Americans expect to provide and receive care. Using broad categories like “family” may miss distinctions in gendered expectations (Folbre, 2002; Spillman et al., 2014), and care roles within diverse family forms (Ganong & Coleman, 1998). Future research could also tease apart preferences between caregivers and care receivers, as preferences and satisfaction with care may differ between older adults and their families (Levin & Kane, 2006). Finally, and importantly, omitted variable bias may be an issue with current models whereby unmeasured confounding variables are related to both educational attainment and eldercare attitudes. Future research should continue to measure and investigate other potential explanatory factors in the association between education and caregiving attitudes, including trust in different institutions, social stigmas associated with particular institutions, and more information about the respondent’s resources and caregiving experiences. Despite these limitations, this study provides an important contribution to the literature by establishing a baseline understanding of the association between educational attainment and attitudes toward combinations of provisions of IADL eldercare in the U.S.

Conclusion

Educational attainment is associated with stratified eldercare attitudes toward provisions of IADL care for older adults in the U.S. Given an aging population and increasing need for care, it is important to consider the ways in which education may create unequal outcomes for older adults in the same way that national level educational attainment shifts have led to “diverging destinies” for children (McLanahan, 2004). This study also adds to a growing literature that finds disparate family outcomes (Cherlin, 2014) and policy solutions desired among different socioeconomic classes in the U.S. regarding family caregiving (Silverstein & Parrott, 2001). The association between education and attitudes is especially important considering the U.S.’s limited set of policies that help caregiving families (Rocco, 2017), and the disconnect between current policies and needs of the public (Henderson et al., 1995; Moen & DePasquale, 2017). Caregiving policies that have the potential to positively influence other public arenas, including health or employment, may receive more public support (Meyer, Rath, Gassoumis, Kaiser, & Wilber, 2019). If the U.S. continues to encourage family care of older adults over institutionalized care, other types of supports, including partnerships between the family and outside institutions, may be necessary to care for all older Americans.

Acknowledgements:

Thank you to the editor and anonymous reviewers for thoughtful feedback. Thank you to Rachel Margolis, Molly A. Martin, Léa Pessin, Anna Zajacova, Paul R. Amato, Melissa Hardy, Sarah Damaske, and the PSU PRI Family Working Group for helpful feedback. This work was supported by the Joint Programming Initiative, More Years Better Lives funding from the Canadian Institute of Health Research (MYB-150262); Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (435-2017-0618, 890-2016-9000); the Penn State PRI’s infrastructure grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) (R24-HD041025); and an NICHD Family Demography Traineeship (T-32HD007514).

References

- Adams PF, & Martinez ME (2016). Percentage of Adults with Activity Limitations, by Age Group and Type of Limitation. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm6501a6.htm

- Albertini M, & Pavolini E (2017). Unequal inequalities: The stratification of the use of formal care among older Europeans. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(3), 510–521. 10.1093/geronb/gbv038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwin DF (1996). Coresidence beliefs in American society - 1973 to 1991. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(21582), 393–403. 10.2307/353504 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barczyk D, & Kredler M (2018). Evaluating long-term-care policy options, taking the family seriously. Review of Economic Studies, 85(2), 766–809. 10.1093/restud/rdx036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune M, Quadagno J, & Blekesaune M (2003). Public Attitudes toward Welfare State Policies : A Comparative Analysis of 24 Nations. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 415–427. [Google Scholar]

- Bookman A, & Kimbrel D (2011). Families and Elder Care in the Twenty-First Century. The Future of Children, 21(2), 117–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody EM, Johnsen PT, & Fulcomer MC (1984). What should adult children do for elderly parents? Opinions and preferences of three generations of women. Journal of Gerontology, 39(6), 736–746. 10.1093/geronj/39.6.736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SL, & Lin I (2012). The Gray Divorce Revolution: Rising Divorce Among. 2Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67(6), 731–741. 10.1093/geronb/gbs089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr JA, Mutchler JE, & Warren JP (2005). State commitment to home and community-based services: effects on independent living for older unmarried women. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 17(1), 1–18. 10.1300/J031v17n01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C, & Horowitz J (2016). Does College Influence Sociopolitical Attitudes? Sociology of Education, 89(1), 40–58. 10.1177/0038040715617224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Limitations in Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, 2003–2007. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adl_tables.htm

- Cherlin A (2014). Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America. New York, NY: The Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. (2013). Rising Demand for Long-Term Services and Supports for Elderly People. Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/scholar?q=Rising+demand+for+long-term+services+and+supports+for+elderly+people&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C44#0 [Google Scholar]

- Eifert EK, Adams R, Morrison S, & Strack R (2016). Emerging Trends in Family Caregiving Using the Life Course Perspective: Preparing Health Educators for an Aging Society. American Journal of Health Education, 47(3), 176–197. 10.1080/19325037.2016.1158674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G (1990). The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Family Caregiver Alliance. (n.d.). National Policy Statement. Retrieved from https://www.caregiver.org/national-policy-statement

- Feinberg LF, Wolkwitz K, & Goldstein C (2006). Ahead of the Curve: Emerging Trends and Practices in Family Caregiver Support. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Finley NJ, Roberts MD, & Banahan BF (1988). Motivators and Inhibitors of Attitudes of Filial Obligation Toward Aging Parents. The Gerontologist, 28(1), 73–78. 10.1093/geront/28.1.73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folbre N (2002). The Invisible Heart: Economics and Family Values. New York, NY: The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fong C (2001). Social preferences, self-interest, and the demand for redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 82(2), 225–246. [Google Scholar]

- Ganong LH, & Coleman M (1998). Attitudes regarding filial responsibilities to help elderly divorced parents and stepparents. Journal of Aging Studies, 12(3), 271–290. 10.1016/S0890-4065(98)90004-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganong LH, & Coleman M (2005). Measuring Intergenerational Obligations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 1003–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Duval S, Anderson KA, & Kane RL (2007). Predicting nursing home admission in the U.S: A meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics, 7. 10.1186/1471-2318-7-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Social Survey. (2018). Weighting Help. Retrieved from https://gssdataexplorer.norc.org/pages/show?page=gss%2Fweighting

- Glenn EN (2010). Forced to care: Coercion and caregiving in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glynn SJ, Boushey H, & Berg P (2016). Who Gets Time Off? Predicting Access to Paid Leave and Workplace Flexibility. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley RJ, Wiener JM, & Harris KM (1991). Will Paid Home Care Erode Informal Support? Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 16(3), 507.2–521. 10.1215/03616878-16-3-507a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays S (1998). The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Jersey: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson TL, Monroe PA, Garand JC, & Burts DC (1995). Explaining Public Opinion toward Government Spending on Child Care. Family Relations, 44(1), 37–45. 10.2307/584739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henly JR, Shaefer HL, & Waxman E (2006). Nonstandard Work Schedules: Employer- and Employee-Driven Flexibility in Retail Jobs. Social Service Review, 80(4), 609–634. 10.1086/508478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hout M (2012). Social and Economic Returns to College Education in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 38(1), 379–400. 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102503 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman MR, & Muha MJ (1984). Education and Intergroup Attitudes: Moral Enlightenment, Superficial Democratic Commitment, or Ideological Refinement? American Sociological Review, 49(6), 751–769. [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby WG (1994). Public Attitudes toward Government Spending. American Journal of Political Science1, 38(2), 336–361. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi R, Oppenheimer AJ, Lee DS, Lepar FH, & Espenshade TJ (1992). Aging in America: Limits to life span and elderly care options. Population Research and Policy Review, 11(2), 169–190. 10.20595/jjbf.19.0_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M, & Kraaykamp G (2007). Social stratification and attitudes: A comparative analysis of the effects of class and education in Europe. British Journal of Sociology, 58(4), 547–576. 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00166.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane EW (1995). Education and Beliefs about Gender Inequality. Social Problems, 42(1), 74–90. 10.3868/s050-004-015-0003-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RL, Lum TY, Kane RA, Homyak P, Parashuram S, & Wysocki A (2013). Does Home- and Community-Based Care Affect Nursing Home Use? Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 25(2), 146–160. 10.1080/08959420.2013.766069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp CL, Ball MM, Morgan JC, Doyle PJ, Burgess EO, & Perkins MM (2018). Maneuvering Together, Apart, and at Odds: Residents’ Care Convoys in Assisted Living. Journals of Gerontology -Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(4), e13–e23. 10.1093/geronb/gbx184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knickman JR, & Snell EK (2002). The 2030 problem: caring for aging baby boomers. Health Services Research, 37(4), 849–884. 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.56.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerin BB, Harrigan MP, & Secret M (2008). Eldercare and employed caregivers: a public/private responsibility? Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 51(1–2), 143–161. 10.1080/01634370801967612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin CA, & Kane RA (2006). Resident and Family Perspectives on Assisted Living. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 18(3–4), 193–209. 10.1300/J031v18n03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li LW (2005). Longitudinal changes in the amount of informal care among publicly paid home care recipients. Gerontologist, 45(4), 465–473. 10.1093/geront/45.4.465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair CA, Chen F, Liu G, & Brauer JR (2016). Who in the World Cares? Gender Gaps in Attitudes toward Support for Older Adults in 20 Nations. Social Forces, 95(1), 411–438. 10.1093/sf/sow049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marcum CS, & Treas J (2013). The Intergenerational Social Contract Revisited. In Silverstein M & Giarrusso R (Eds.), Kinship and Cohort in an Aging Society: From Generation to Generation (pp. 293–313). Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R (2013). Educational Differences in Healthy Behavior Changes and Adherence Among Middle-aged Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(3), 353–368. 10.1177/0022146513489312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolis R, & Verdery AM (2017). Older Adults Without Close Kin in the United States. Journals of Gerontology - Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 72(4), 688–693. 10.1093/geronb/gbx068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S (2004). Diverging Destinies: How Children are Faring Under the Second Demographic Transition. Demography, 41(4), 607–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute. (2011). The MetLife Study of Caregiving Costs to Caregivers The MetLife Study of Caregiving Costs to Working Caregivers: Double Jeopardy for Baby Boomers Caring for Their Parents. Westport, CT. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer K, Rath L, Gassoumis Z, Kaiser N, & Wilber K (2019). What Are Strategies to Advance Policies Supporting Family Caregivers? Promising Approaches From a Statewide Task Force. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 31(1), 66–84. 10.1080/08959420.2018.1485395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills CW (1959). The Sociological Imagination. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P, & DePasquale N (2017). Family care work: a policy-relevant research agenda. International Journal of Care and Caring, 1(1), 45–62. 10.1332/239788217X14866284542346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery RJV (1999). The Family Role in the Context of Long-Term Care. Journal of Aging and Health, 11(3), 383–416. 10.1177/089826439901100307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin R, & Neidorf S (2007). Surge in Support for Social Safety Net. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/2007/05/02/surge-in-support-for-social-safety-net/

- Myles J (2002). A New Social Contract for the Elderly? In Esping-Andersen G, Gallie D, Hemerijck A, & Myles J (Eds.), Why we need a new welfare state (pp. 130–172). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olson LK (1994). The graying of the world: who will care for the frail elderly? New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko EK (2011). Caregiving and the Life Course: Connecting the Personal and the Public. In Settersten RA & Angel JL (Eds.), Handbook of Sociology of Aging (pp. 603–616). Neuva York. 10.1007/978-1-4419-7374-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. (2015). Family Support in a Graying Society: How Americans, Germans, and Italians are Coping with an Aging Population. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan J, Link BG, Stueve A, & Moore RE (1995). Education, Social Liberalism, and Economic Conservatism: Attitudes Toward Homeless People. American Sociological Review, 60(1), 126–140. [Google Scholar]

- Powell B, Bolzendahl C, Geist C, & Steelman L (2010). Counted Out: Same-Sex Relations and Americans’ Defintions of Family. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Preston SH (1984). Children and the Elderly: Divergent Paths for America’s Dependents. Demography, 21(4), 435–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reckrey JM, Federman AD, Bollens-Lund E, Morrison RS, & Ornstein KA (2019). Homebound Status and the Critical Role of Caregiving Support. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 00(0), 1–14. 10.1080/08959420.2019.1628625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee Y, Degenholtz HB, Lo Sasso AT, & Emanuel LL (2009). Estimating the quantity and economic value of family caregiving for community-dwelling older persons in the last year of life. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 57(9), 1654–1659. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02390.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocco P (2017). Informal Caregiving and the Politics of Policy Drift in the United States. Journal of Aging and Social Policy, 29(5), 413–432. 10.1080/08959420.2017.1280748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CL, & Bauman K (2016). Educational Attainment in the United States. United States Census Bureau (Vol. 2010). Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p20-578.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel L (2018). Education and Attitudes toward Interpersonal and State-Sanctioned Violence. PS - Political Science and Politics, (July), 1–7. 10.1017/S1049096518000094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz E, Jutz R, Edlund J, Oun I, & Braun M (2014). ISSP 2012 Family and Changing Gender Roles IV: Questionairre Development. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M (2006). Intergenerational transfers in social context. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences, 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Angelelli JJ, & Parrott TM (2001). Changing attitudes toward aging policy in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s: a cohort analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci, 56(1), S36–43. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11192344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, & Giarrusso R (2010). Aging and family life: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1039–1058. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00749.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, & Parrott TM (1997). Attitudes Toward Public Support of the Elderly. Research on Aging, 19(1), 108–132. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, & Parrott TM (2001). Attitudes toward Government Policies that Assist Informal Caregivers: The Link between Personal Troubles and Public Issues. Research on Aging, 23(3), 349–374. 10.1177/0164027501233004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spillman BC, Wolff J, Freedman V, & Kasper JD (2014). Informal Caregiving for Older Americans: An Analysis of the 2011 National Study of Caregiving. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes B (2013). Public Attitudes Toward the Next Social Contract. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2013/01/15/public-attitudes-toward-the-next-social-contract/

- Svallfors S (1997). Worlds of Welfare and Attitudes to Redistribution: A Comparison of Eight Western Nations. European Sociological Review, 13(3), 283–304. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A (1989). Changing Attitudes toward Family Issues in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 51(4), 873–893. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton A, Alwin DF, & Camburn D (1983). Causes and Consequences of Sex-Role Attitudes and Attitude Change. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 211–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel PT (2007). Regression with Missing Ys: An Improved Strategy for Analyzing Multiply Imputed Data. Sociological Methodology, 37(1), 83–117. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ, & Feinberg LF (2006). Family and Friends as Respite Providers. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 18(3–4), 37–41. 10.1300/J031v18n03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Spillman BC, Freedman VA, & Kasper JD (2016). A national profile of family and unpaid caregivers who assist older adults with health care activities. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(3), 289–313. 10.1007/s11065-015-9294-9.Functional [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang P, & Barrett N (2006). Understanding public attitudes towards Social Security. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(2), 95–109. 10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00382.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]