Abstract

The conserved ATPase, PCH-2/TRIP13, is required during both the spindle checkpoint and meiotic prophase. However, its specific role in regulating meiotic homolog pairing, synapsis and recombination has been enigmatic. Here, we report that this enzyme is required to proofread meiotic homolog interactions. We generated a mutant version of PCH-2 in C. elegans that binds ATP but cannot hydrolyze it: pch-2E253Q. In vitro, this mutant can bind a known substrate but is unable to remodel it. This mutation results in some non-homologous synapsis and impaired crossover assurance. Surprisingly, worms with a null mutation in PCH-2’s adapter protein, CMT-1, the ortholog of p31comet, localize PCH-2 to meiotic chromosomes, exhibit non-homologous synapsis and lose crossover assurance. The similarity in phenotypes between cmt-1 and pch-2E253Q mutants suggest that PCH-2 can bind its meiotic substrates in the absence of CMT-1, in contrast to its role during the spindle checkpoint, but requires its adapter to hydrolyze ATP and remodel them.

Author summary

The production of sperm and eggs for sexual reproduction depends on meiosis. During this specialized cell division, homologous chromosomes pair, synapse and undergo meiotic recombination so that they are linked by at least one chiasma to promote their proper segregation. How homologous chromosomes ensure that these important interactions are with the correct partner is currently unknown. Here, we show that PCH-2 and its adapter protein, CMT-1, proofread homolog interactions to promote their fidelity and proper meiotic chromosome segregation.

Introduction

Sexual reproduction relies on meiosis, the specialized cell division that generates haploid gametes, such as sperm and eggs, from diploid progenitors so that fertilization restores diploidy. To ensure that gametes inherit the correct number of chromosomes, meiotic chromosome segregation is exquisitely choreographed: Homologous chromosomes segregate in meiosis I and sister chromatids segregate in meiosis II. Having an incorrect number of chromosomes, also called aneuploidy, is associated with infertility, miscarriages and birth defects, underscoring the importance of understanding this process to human health.

Events in meiotic prophase ensure proper chromosome segregation. During prophase, homologous chromosomes undergo progressively intimate interactions that culminate in synapsis and crossover recombination (reviewed in [1]). After homologs pair, a macromolecular complex, called the synaptonemal complex (SC), is assembled between them in a process called synapsis. Synapsis is a prerequisite for crossover recombination to generate the linkages, or chiasmata, between homologous chromosomes that direct meiotic chromosome segregation [2–8]. Defects in any of these events can result in chromosome missegregation during the meiotic divisions and gametes, and therefore embryos, with an incorrect number of chromosomes.

Coordinating the events of pairing, synapsis and crossover recombination is essential for their proper progression. For example, defects that uncouple pairing and synapsis can produce situations in which non-homologous chromosomes are inappropriately synapsed and unable to undergo crossover recombination. Mutations that produce non-homologous synapsis often identify mechanisms that are important for homolog pairing. For example, in maize, budding yeast and mice, where the initiation of meiotic recombination plays an integral role in promoting accurate homolog pairing and synapsis, mutations in genes involved in homologous recombination can produce non-homologous synapsis to varying degrees [9–17]. In Drosophila and C. elegans, two organisms in which correct pairing and synapsis can occur independent of recombination events [18, 19], other mechanisms ensure correct homologous synapsis, including integrity of meiotic chromosome axes [20–23], highly regulated chromosome movement [24, 25], centromere clustering [26] and specific histone modifications [27].

Despite these differences, in most organisms, the conserved AAA-ATPase PCH-2 (Pch2 in budding yeast, PCH2 in Arabidopsis and Drosophila and TRIP13 in mice) is crucial to coordinate events in meiotic prophase. In vitro and cytological experiments indicate that it does this by using the energy of ATP hydrolysis to remodel meiotic HORMADs [28–32], chromosomal proteins that are essential for pairing, synapsis, recombination and checkpoint function [20–22, 33–41]. HORMADs are a protein family defined by the ability of a domain, the HORMA domain, to adopt multiple conformations that specify protein function [42–44]. Meiotic HORMADs appear to adopt two conformations: a “closed” version, that forms upon binding a short peptide within other proteins [45]; and a more extended, or “unlocked,” version [46]. The closed form of meiotic HORMADs assemble on meiotic chromosomes to drive pairing, synapsis and recombination [45]. The physiological relevance of the unlocked version is unknown.

Cytological experiments in budding yeast, plants and mice show that PCH-2 removes or redistributes meiotic HORMADs on chromosomes [28, 30–32]. This change in localization both contributes to and reflects the progression of meiotic prophase events [28, 30–32]. However, major events in meiotic prophase, such as pairing, synapsis initiation and recombination, precede the removal or redistribution of meiotic HORMADs, raising the question of how PCH-2 affects these events to produce the phenotypes reported in its absence. Indeed, the phenotypes associated with loss of PCH2 are inconsistent with its only role being the redistribution of meiotic HORMADs [47–49]. In C. elegans, PCH-2 regulates meiotic prophase events but not the localization of meiotic HORMADs [50], indicating that 1) the removal or relocalization of meiotic HORMADs is not essential for PCH-2’s effects on pairing, synapsis and recombination; and 2) this model organism is particularly relevant to better understand how PCH-2 regulates these events.

We previously showed that in the absence of PCH-2, homolog pairing, synapsis and recombination are accelerated and associated with an increase in meiotic defects, leading us to speculate that PCH-2 disassembles molecular intermediates between homologous chromosomes that underlie these events to ensure their fidelity [50]. Specifically, we hypothesized that these molecular intermediates involve meiotic HORMADs and PCH-2 remodels meiotic HORMADs to proofread these homolog interactions [50]. To test this model, we generated a mutant version of PCH-2 that binds ATP, and its substrates, but cannot hydrolyze ATP and therefore cannot remodel and release its substrates. We reasoned that if our hypothesis is correct, this mutant protein will “trap,” and allow us to more easily visualize, inappropriate homolog interactions that are incorrectly stabilized. This is accurate: pch-2E253Q mutants delay homolog pairing and accelerate synapsis, producing non-homologous synapsis. Meiotic DNA repair occurs with normal kinetics but crossover assurance is lost, suggesting that crossover-specific recombination intermediates between incorrect partners may also be inappropriately stabilized. Surprisingly, loss of CMT-1, an adapter protein that is thought to be essential for PCH-2 to bind its substrates, phenotypically resembles pch-2E253Q mutants. Since PCH-2 localizes normally to meiotic chromosomes in the absence of CMT-1, these data indicate that CMT-1 is dispensable for PCH-2 to bind its meiotic substrates on chromosomes but is essential to hydrolyze ATP and remodel its substrates.

Results

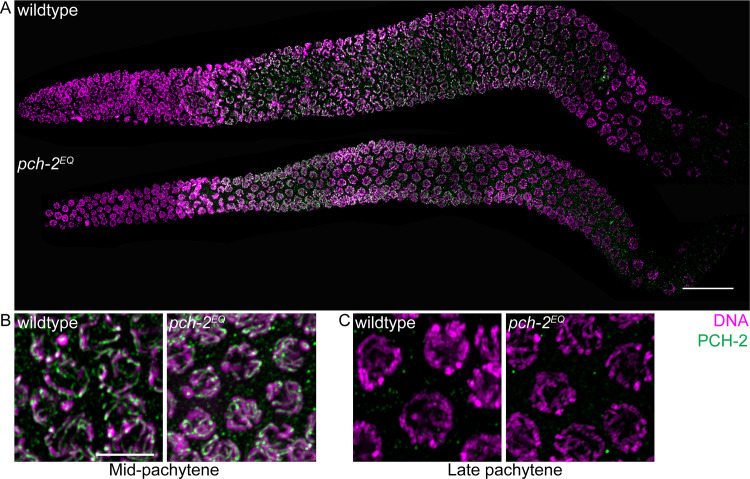

PCH-2E253Q localizes normally during meiotic prophase

We introduced a mutation by CRISPR/Cas9 genomic editing [51, 52] in the Walker B motif of PCH-2, E253Q, that allows it to bind ATP, but not hydrolyze it. We designated this allele pch-2(blt5) but will refer to it as pch-2E253Q (pch-2EQ in Figures). In budding yeast, this mutation abolishes PCH-2’s in vivo meiotic function [29]. In vitro, PCH-2E253Q retains high affinity nucleotide binding, forms stable hexamers and interacts with its substrates [53]. In meiotic nuclei, PCH-2E253Q localized normally to meiotic chromosomes (Fig 1A, grayscale images in S4A Fig), appearing as foci just prior to the entry into meiosis (also known as the transition zone) and co-localizing with the synaptonemal complex once synapsis had initiated (Fig 1B, grayscale images in S4B Fig). It was also removed from the synaptonemal complex in late pachytene, similar to wildtype PCH-2 (Fig 1C, grayscale images in S4C Fig).

Fig 1. PCH-2E253Q localizes to meiotic chromosomes similar to wildtype PCH-2.

A. Whole germline images of PCH-2 and DAPI staining in a wildtype and pch-2E253Q mutant germline. Scale bar indicates 20 microns. Meiotic nuclei in mid-pachytene (B) and late pachytene (C) stained with DAPI and antibodies against PCH-2 in wildtype animals and pch-2E253Q mutants. Unless otherwise stated, all scale bars indicate 5 microns.

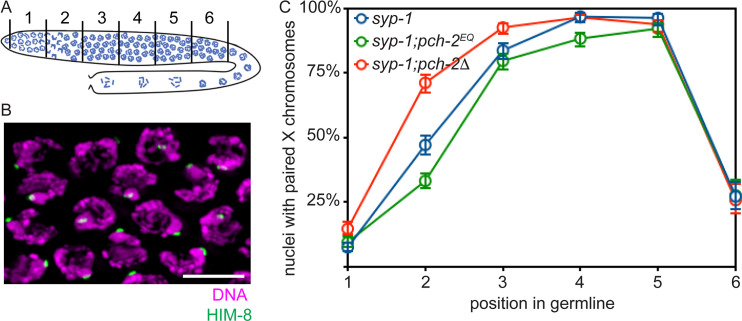

pch-2E253Q mutants delay pairing

Next, we analyzed pairing in syp-1 mutants. SYP-1 is a component of the synaptonemal complex (SC), and syp-1 mutants fail to assemble SC between paired homologs, allowing us to more easily visualize pairing intermediates in the absence of synapsis [6]. In C. elegans, cis-acting sites called pairing centers (PCs) are required for pairing and synapsis [54]. In the absence of synapsis, homologous chromosomes exhibit stable pairing of PC, but not non-PC, ends of chromosomes [54]. We monitored synapsis-independent pairing at PC sites by performing immunofluorescence against HIM-8, which binds PCs of X chromosomes [55] (Fig 2B). A single focus of HIM-8 indicates paired X chromosomes while two foci indicate unpaired X chromosomes. When we imaged stained germlines, we divided germlines into six equal sized zones (see cartoon in Fig 2A). Because meiotic nuclei are arranged spatiotemporally in the germline, this allows us to assess pairing as a function of meiotic progression.

Fig 2. Homolog pairing is delayed in pch-2E253Q mutants.

A. Cartoon of C. elegans germline divided into six equivalent zones. B. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with DAPI and antibodies against HIM-8. C. Timecourse of X chromosome pairing in wildtype, pch-2E253Q and pch-2Δ mutant germlines. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

syp-1 mutants initiated pairing in zone 2, maintained pairing at the X chromosome PC in zones 3,4 and 5 and destabilized pairing in zone 6 (Fig 2C). As we previously reported [50], syp-1;pch-2Δ double mutants also initiated PC pairing in zone 2 but had significantly more nuclei with paired HIM-8 signals than syp-1 single mutants (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test), indicating that pairing is accelerated in this background. By contrast, syp-1; pch-2E253Q double mutants had significantly fewer nuclei with paired HIM-8 signals in zone 2 than both syp-1 single (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) and syp-1;pch-2Δ double mutants (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). In later zones, all three genotypes closely resembled each other in that chromosomes are paired. However, in zone 4, significantly fewer X chromosomes were paired in syp-1; pch-2E253Q double mutants than syp-1 single mutants (p value = 0.0003, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). Thus, syp-1; pch-2E253Q mutants delay and exhibit defects in pairing at PCs, consistent with our model that PCH-2 proofreads homolog pairing intermediates: If pch-2E253Q mutants “trap” incorrect pairing intermediates, between non-homologous chromosomes, for example, this would affect pairing between homologous chromosomes.

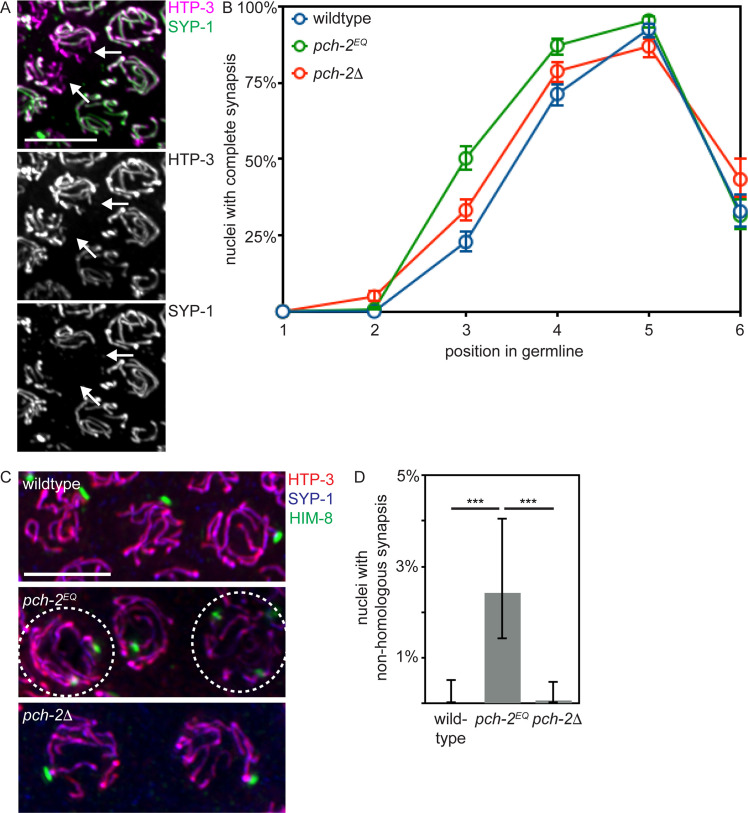

pch-2E253Q mutants accelerate synapsis and produce non-homologous synapsis

Next, we assayed synapsis by monitoring the colocalization of two SC components, HTP-3 and SYP-1 [6, 54]. When HTP-3 and SYP-1 colocalize, chromosomes are synapsed while regions of HTP-3 devoid of SYP-1 are unsynapsed (see arrows in Fig 3A). We evaluated the percentage of nuclei that had completed synapsis as a function of meiotic progression (Fig 3B). In contrast to our analysis of pairing, synapsis in pch-2E253Q mutants was accelerated, similar to but even more severely than pch-2Δ mutants (Fig 3B and [50]) (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test): More nuclei had completely synapsed chromosomes when synapsis initiates in zone 3 in pch-2E253Q mutants than control germlines (Fig 3B) (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). In contrast to pch-2Δ mutants, pch-2E253Q mutants did not exhibit defects in SC disassembly in zone 6 (Fig 3B and [50]).

Fig 3. Synapsis is accelerated in pch-2E253Q mutants, producing non-homologous synapsis.

A. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with antibodies against HTP-3 and SYP-1. Color and grey scale images are provided. Arrows indicate unsynapsed chromosomes. B. Timecourse of synapsis in wildtype, pch-2E253Q and pch-2Δ mutant germlines. C. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with antibodies against HTP-3, SYP-1 and HIM-8 in wildtype animals, pch-2E253Q and pch-2Δ mutants. Circled nuclei have undergone non-homologous synapsis. D. Quantification of non-homologous synapsis wildtype animals, pch-2E253Q and pch-2Δ mutants. All error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed Fisher exact tests. A *** indicates a p value < 0.0001.

We reasoned that the delay in pairing, combined with the acceleration in synapsis, raised the possibility that these events, which are typically coupled, had been uncoupled. To test this possibility, we evaluated whether non-homologous synapsis occurs in pch-2E253Q mutants. We stained wildtype, pch-2Δ and pch-2E253Q mutant germlines with antibodies against SC components HTP-3 and SYP-1 to evaluate synapsis and HIM-8 to assess pairing. All nuclei in wildtype animals, pch-2Δ, and most nuclei in pch-2E253Q mutants exhibited homologous synapsis (uncircled nuclei in Fig 3C). However, we identified meiotic nuclei in which all chromosomes were synapsed but contained two HIM-8 foci, indicating these chromosomes had synapsed with non-homologous partners (circled nuclei in Fig 3C). We also observed non-homologous synapsis when we monitored pairing of autosomes using antibodies against ZIM-2, a protein that binds an autosomal PC [56] (S1A Fig). When we quantified this defect, we detected non-homologous synapsis of X chromosomes in 2.5% of meiotic nuclei (Fig 3D) and non-homologous synapsis of Chromosome V in 6% of meiotic nuclei (S1B Fig). Unlike HIM-8 [55], ZIM-2 only stains meiotic chromosomes in a subset of meiotic nuclei [56]. Since fewer nuclei are positive for ZIM-2 than HIM-8 in all germlines, this explains the higher frequency of non-homologous synapsis that involves Chromosome V. C. elegans have six pairs of homologous chromosomes. Therefore, it’s possible that as many as 18% of meiotic nuclei have at least one pair of chromosomes undergoing non-homologous synapsis in pch-2E253Q mutants. However, it’s also formally possible that some nuclei contain multiple pairs of chromosomes that are non-homologously synapsed and that 18% may be an overstatement. Unfortunately, we were unable to directly test this possibility due to technical limitations.

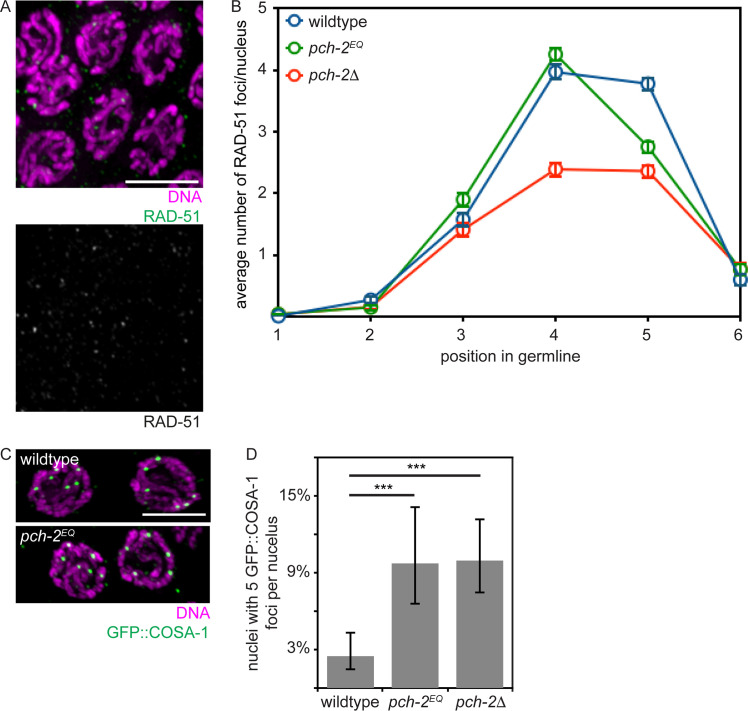

pch-2E253Q mutants lose crossover assurance

We then monitored meiotic DNA repair and the formation of crossovers. To assess DNA repair, we monitor the appearance and disappearance of RAD-51 from meiotic chromosomes as a function of meiotic progression (Fig 4A). RAD-51 is required for all meiotic DNA repair in C. elegans [57]. Its appearance on chromosomes signals the formation of double strand breaks (DSBs) that need to be repaired (see zones 3 and 4 in wildtype in Fig 4B) and its disappearance indicates the entry of DSBs into a DNA repair pathway (see zones 5 and 6 in wildtype in Fig 4B) [3]. The appearance and disappearance of RAD-51 on meiotic chromosomes in pch-2E253Q mutants was indistinguishable from that in wildtype in zones 1–4. In zone 5, we detected fewer RAD-51 foci, suggesting that meiotic DNA repair may occur slightly more rapidly in pch-2E253Q mutants (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed t- test). However, we observed an acceleration in DNA repair much earlier in pch-2Δ mutants (see zone 4, Fig 4B and [50] (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed t-test).

Fig 4. Meiotic DNA repair is not affected in pch-2E253Q mutants but crossover assurance is.

A. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with DAPI and antibodies against RAD-51. Color and grey scale images are provided. B. Timecourse of the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus in wildtype, pch-2E253Q and pch-2Δ mutant germlines. Error bars indicate 2XSEM. C. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with DAPI and antibodies against GFP. D. Percentage of nuclei with five GFP::COSA-1 foci in wildtype animals, pch-2E253Q and pch-2Δ mutants. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed Fisher exact tests. A *** indicates a p value < 0.0001.

We assayed crossover formation in pch-2E253Q mutants by visualizing GFP::COSA-1 foci formation in late meiotic prophase. GFP::COSA-1 cytologically marks putative crossovers and its appearance as robust foci is mechanistically associated with the process of crossover designation [58]. Almost all nuclei in wildtype worms had six GFP::COSA-1 foci per nucleus, one per homolog pair (Fig 4C, top, and 4D) [58]. In contrast, pch-2E253Q mutants had a greater number of nuclei with five GFP::COSA-1 foci, similar to pch-2Δ mutants, indicating a defect in crossover assurance (Fig 4C, bottom, 4D and [50]). Given the in vitro behavior of the PCH-2E253Q hexamer [53], this phenotype is likely because inappropriate crossover intermediates are stabilized at the expense of appropriate ones. Alternatively, these meiotic nuclei may result from the non-homologous synapsis we also observe in this mutant background. However, we do not observe a delay in meiotic DNA repair in pch-2E253Q mutants (Fig 4B). Further, pch-2E253Q mutants do not activate feedback mechanisms, as visualized by the extension of DSB-1 on meiotic chromosomes [59, 60] (S2A and S2B Fig). Therefore, we favor the first interpretation.

CMT-1 is required for the synapsis checkpoint

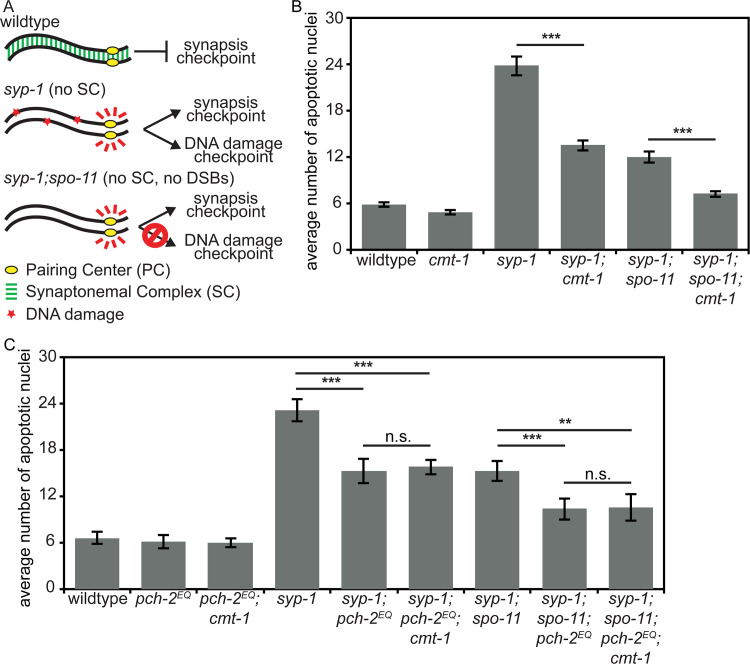

During the spindle checkpoint, PCH-2 requires the presence of an adapter protein, CMT-1 (p31comet in mammalian cells), to bind and remodel a HORMAD protein required for the spindle checkpoint response, Mad2 [53, 61, 62]. Based on a recent report that the rice ortholog of CMT-1 is an SC component and required for pairing, synapsis and double strand break formation [63], we tested whether cmt-1 had a role in meiotic prophase by assessing whether it was required for meiotic prophase checkpoints in C. elegans. We introduced a null mutation of cmt-1 into syp-1 mutants. The absence of SC in syp-1 mutants results in unsynapsed chromosomes, which activate very high levels of germline apoptosis in response to both the synapsis and the DNA damage checkpoints [64] (Fig 5A). cmt-1 single mutants had wildtype levels of apoptosis (Fig 5B). In contrast to syp-1 single mutants, syp-1;cmt-1 double mutants had intermediate levels of germline apoptosis (Fig 5B), indicating that CMT-1 is required for either the synapsis or DNA damage checkpoint. To distinguish between these two checkpoints, we used syp-1;spo-11 double mutants, which do not generate double strand breaks [18]. As a result, these double mutants do not activate the DNA damage checkpoint (Fig 5A) and produced an intermediate level of apoptosis (Fig 5B). [64]. When we generate syp-1;spo-11;cmt-1 triple mutants, we observed wildtype levels of apoptosis, similar to but slightly higher than cmt-1 single mutants (Fig 5B) (p value < 0.05, two tailed t-test). Therefore, CMT-1 is required to activate apoptosis in response to the synapsis checkpoint, similar to pch-2Δ mutants.

Fig 5. CMT-1 is required for the synapsis checkpoint.

A. Cartoon of meiotic checkpoint activation in C. elegans. B. Mutation of cmt-1 reduces apoptosis in syp-1 single mutants and syp-1;spo-11 double mutants. Error bars indicate 2XSEM. C. pch-2E253Q reduces apoptosis in syp-1 and syp-1;spo-11 mutants but not in syp-1;cmt-1 or syp-1;spo-11;cmt-1 mutants. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed t-tests. A *** indicates a p value < 0.0001, a ** indicates a p value < 0.01 and an n.s. indicates not significant.

cmt-1 mutants phenotypically resemble pch-2E253Q mutants

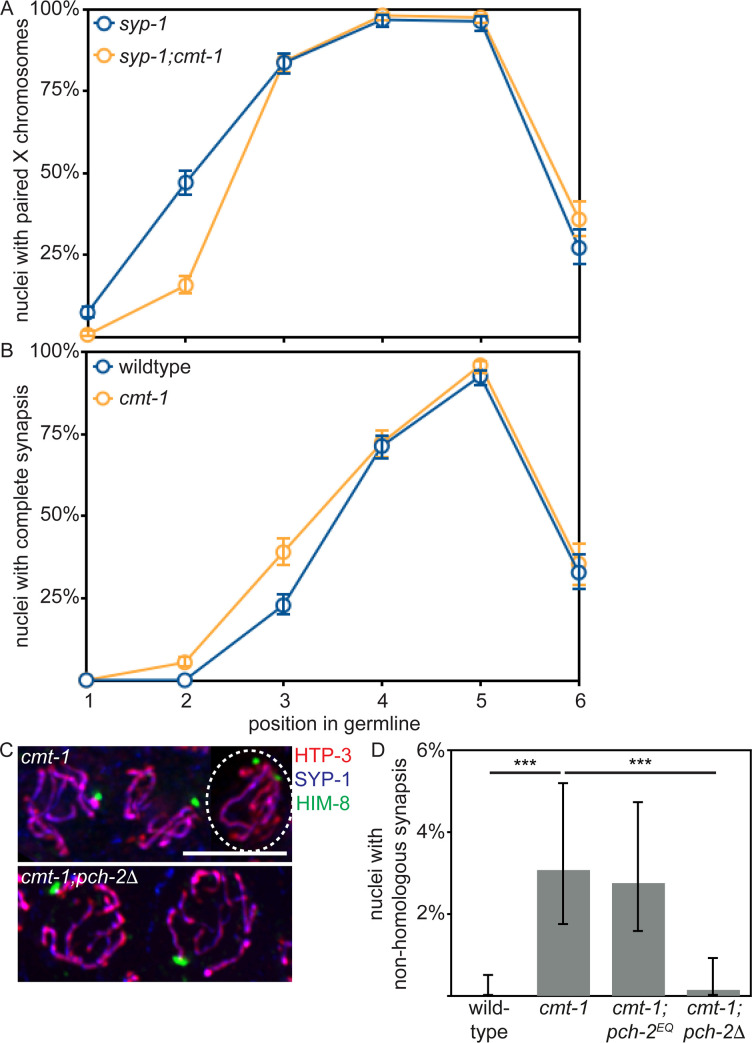

Based on the requirement for CMT-1 in the synapsis checkpoint, we assessed pairing, synapsis, meiotic DNA repair and crossover formation in cmt-1 mutants. Similar to our analysis of pch-2E253Q mutants, pairing was delayed in syp-1;cmt-1 double mutants (see zone 2, Fig 6A) (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test) and synapsis was accelerated in cmt-1 single mutants (see zone 3, Fig 6B) (p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). We also detected non-homologous synapsis at levels similar to that of pch-2E253Q mutants (Figs 6C, 6D and S1). Meiotic DNA repair in cmt-1 mutants, as visualized by the appearance and disappearance of RAD-51 (S3A Fig), and meiotic progression, as visualized by the appearance and disappearance of a protein required for DSB formation, DSB-1 (S2A and S2B Fig), closely resembled that of wildtype germlines. However, we did observe a delay in RAD-51 removal in cmt-1 mutants (zones 5 and 6, p value < 0.0001, two-tailed Fisher’s exact test). It is unclear whether this delay is biologically relevant, since we only observe a slight delay in DSB-1 removal (S2B Fig). In addition, crossover assurance was reduced (S3B Fig).

Fig 6. cmt-1 mutants delay pairing, accelerate synapsis and exhibit non-homologous synapsis, similar to pch-2E253Q mutants.

A. Timecourse of pairing in wildtype and cmt-1 mutant germlines. B. Timecourse of synapsis in wildtype and cmt-1 mutant germlines. C. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with antibodies against HTP-3, SYP-1 and HIM-8 in cmt-1 and cmt-1;pch-2Δ mutants. The circled nucleus has undergone non-homologous synapsis. D. Quantification of non-homologous synapsis wildtype animals, cmt-1, cmt-1;pch-2E253Q and cmt-1;pch-2Δ mutants. All error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed Fisher exact tests. A *** indicates a p value < 0.0001.

The meiotic phenotypes of cmt-1 mutants are more similar to that of pch-2E253Q mutants than to that of pch-2Δ mutants, suggesting that PCH-2 can bind its meiotic substrates effectively in the absence of CMT-1 but CMT-1 is required for PCH-2’s hydrolysis of ATP. This is in contrast to PCH-2’s interaction with Mad2, which depends on CMT-1 [53, 61]. Consistent with this interpretation, cmt-1;pch-2E253Q double mutants had a similar frequency of non-homologous synapsis (Fig 6D), nuclei with five GFP::COSA-1 foci (S3B Fig), viable offspring and male-self progeny as either single mutant (Table 1). Finally, syp-1;pch-2E253Q;cmt-1 and syp-1;spo-11;pch-2E253Q;cmt-1 mutants did not exhibit any further reduction in germline apoptosis than syp-1;pch-2E253Q and syp-1;spo-11;pch-2E253Q mutants (Fig 5D) (p values = 0.596 and 0.891, respectively, two-tailed t-tests). Further, since cmt-1 mutants result in meiotic phenotypes distinct from those we reported for spindle checkpoint mutants [65], specifically non-homologous synapsis, CMT-1’s role in meiotic prophase is independent of its regulation of Mad2.

Table 1. Viability and Him phenotype.

| Genotype | % viability (total number of progeny) | % male self-progeny |

|---|---|---|

| wildtype | 100% (3949) | 0.05% |

| cmt-1;pch-2E253Q | 100% (2349) | 0.34% |

| cmt-1 | 100% (3654) | 0.27% |

| pch-2E253Q;cmt-1 | 100% (2721) | 0.25% |

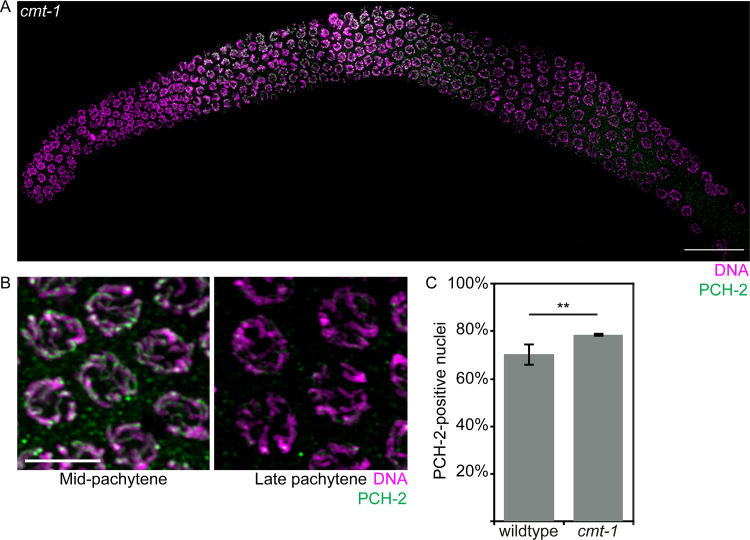

Non-homologous synapsis in cmt-1 mutants relies on PCH-2

We previously showed that CMT-1 is required for PCH-2 to localize to mitotic chromosomes during the spindle checkpoint [66]. We tested whether this was also true during meiotic prophase and found that CMT-1 was dispensable for PCH-2’s localization to meiotic chromosomes (Fig 7A, grayscale images in S4 Fig). Consistent with CMT-1 being required for PCH-2’s hydrolysis of ATP and release of substrates, we observed that PCH-2 stayed on meiotic chromosomes slightly longer than in wildtype germlines (Fig 7C).

Fig 7. PCH-2 localizes to meiotic chromosomes in cmt-1 mutants.

A. Whole germline image of PCH-2 and DAPI staining in a cmt-1 mutant germline. Scale bar indicates 20 microns. B. Meiotic nuclei in mid-pachytene stained with DAPI and antibodies against PCH-2 in cmt-1 mutants. C. Quantification of percentage of PCH-2-positive nuclei in wildtype and cmt-1 mutant germlines. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed t-tests. A ** indicates a p value < 0.01.

During mitotic divisions in the C. elegans embryo, loss of CMT-1 partially suppresses the spindle checkpoint defect observed in pch-2 mutants [66]. Since PCH-2 ensures availability of the inactive conformer of Mad2 so that it can be converted to the active one during checkpoint activation [67, 68], we hypothesize that this genetic interaction results because loss of CMT-1 makes more inactive Mad2 available. In this way, PCH-2 and CMT-1 would control the spindle checkpoint by regulating available, soluble pools of inactive and active Mad2. We wondered if there was a similar relationship between PCH-2 and CMT-1 in meiotic prophase. To test this, we generated cmt-1;pch-2Δ double mutants and assayed non-homologous synapsis. Unlike cmt-1 single mutants and similar to pch-2Δ mutants, we did not detect non-homologous synapsis in cmt-1;pch-2Δ double mutants (Fig 6C and 6D). Thus, PCH-2 is epistatic to CMT-1 during meiosis, at least in the context of non-homologous synapsis, supporting our interpretation that PCH-2 can bind its meiotic substrates independent of CMT-1 and suggesting that some of PCH-2’s regulation of its meiotic substrates occurs directly on chromosomes.

Discussion

In vitro, PCH-2E253Q protein binds ATP and its spindle checkpoint substrate, Mad2, but fails to remodel it, due to an inability to hydrolyze ATP [53]. Here, we show that the meiotic phenotypes observed in pch-2E253Q mutants are consistent with a role for PCH-2 in disassembling inappropriate pairing, synapsis and crossover recombination intermediates in C. elegans, resulting in non-homologous synapsis (Figs 3C, 3D and S1) and a loss of crossover assurance (Fig 4D). The effect we observe on these meiotic prophase events seems limited, affecting a small proportion of nuclei, but this may reflect either the inherent fidelity of these processes or the existence of redundant mechanisms that contribute to fidelity in C. elegans. Further, a role for PCH-2 in proofreading may be more apparent in organisms or situations in which homolog interactions are more challenging. Indeed, PCH-2’s involvement in the interchromosomal effect in Drosophila [69], in which chromosome rearrangements affect crossover control on other chromosomes, supports this possibility. Nevertheless, our results demonstrate that PCH-2 proofreads interactions between homologous chromosomes to ensure that they are correct.

We previously showed that PCH-2 decelerates homolog pairing, synapsis and recombination, coordinating these meiotic prophase events [50]. Here, we argue that PCH-2 acts directly on chromosomes to proofread meiotic interhomolog interactions and ensure their fidelity. This role is supported by several pieces of data. First, PCH-2 localizes to meiotic chromosomes, both before and after synapsis [50]. This localization is functional, as demonstrated by its persistence on the synaptonemal complex and correlation with an extension of homolog access in mutants defective in recombination [50, 70]. Second, despite the defects we report, pch-2Δ, pch-2E253Q and cmt-1 mutants do not show acceleration of meiotic progression, as assayed by SUN-1 phosphorylation [50], appearance of transition zone nuclei (Figs 1 and 7 and [50]), ZIM-2 (S1 Fig) or DSB-1 localization (S2 Fig), indicating that PCH-2 and CMT-1 do not coordinate these meiotic prophase events indirectly through misregulation of meiotic progression. Finally, meiotic defects associated with loss of CMT-1 rely on PCH-2 function (Fig 6D), unlike what we observe in mitosis [66]. In mitosis, CMT-1 is epistatic to PCH-2, which we attribute to misregulation of soluble pools of Mad2. Soluble pools of at least one meiotic HORMAD, HTP-1, have been implicated in ensuring both accurate homolog synapsis and proper meiotic progression [23]. If PCH-2 and CMT-1 were regulating homolog pairing, synapsis and recombination via control of meiotic progression, we might predict that CMT-1 would be epistatic to PCH-2 in meiosis, as it is in mitosis. Taken together, these data favor a model in which PCH-2 and CMT-1 proofread interactions between homologous chromosomes that underlie pairing, synapsis and recombination in C. elegans. Since pairing, synapsis and recombination depend on meiotic HORMADs adopting their closed conformations [45], we hypothesize that these interactions between homologous chromosomes either involve or are stabilized by closed versions of meiotic HORMADs and PCH-2, in collaboration with CMT-1, remodels them to disassemble or destabilize them. In systems such as plants, yeast and mice, we propose that PCH-2 plays a similar role in addition to removing or relocalizing meiotic HORMADs to signal meiotic progression [28, 30–32].

We were surprised to see that PCH-2 localized to meiotic chromosomes in cmt-1 mutants (Fig 7), unlike what we observe during the spindle checkpoint response [66], and that cmt-1 mutants closely resembled pch-2E253Q mutants in exhibiting non-homologous synapsis and a loss of crossover assurance (Figs 6 and S2). Since PCH-2’s localization to meiotic chromosomes depends on synapsis [50], this localization may not accurately represent interaction with its proposed meiotic substrates, meiotic HORMADs. Alternatively, these data may suggest that PCH-2 is competent to bind meiotic HORMADs in the absence of CMT-1 and that CMT-1’s meiotic function is to promote PCH-2’s ATPase activity and ability to remodel these substrates. This is unlike its role in the spindle checkpoint, in which CMT-1/p31comet is essential for PCH-2 to bind its substrate, Mad2 [53, 61, 62, 71]. This difference raises the possibility that the interaction between PCH-2 and meiotic HORMADs during their remodeling is substantially different than that with Mad2. This hypothesis is supported by the findings that budding yeast, in which PCH2 was originally identified [72], does not appear to have a CMT-1/p31comet ortholog [73, 74] and budding yeast Pch2 can directly interact with and remodel the budding yeast meiotic HORMAD, Hop1, in vitro [29]. However, another possibility is that PCH-2’s ability to remodel meiotic HORMADs exists in two modes: 1) a mode that proofreads meiotic interhomolog interactions during pairing, synapsis and recombination and depends on CMT-1 for ATP hydrolysis, but not substrate binding; and 2) one that removes meiotic HORMADs during meiotic progression which relies on CMT-1 for both substrate recognition and ATP hydrolysis. Such a model raises the immediate question of how these two modes might be regulated in an organism with both.

The PCH-2/HORMAD genetic module is evolutionarily ancient [75, 76], having been identified as operons in several bacteria [77], suggesting that this pair of proteins has been co-opted to function in multiple molecular contexts. While we can easily detect an interaction between PCH-2 and CMT-1, and CMT-1 and Mad2, by two-hybrid experiments [66], we have not been able to observe a similar interaction between PCH-2 or CMT-1 and any of the four meiotic HORMADs present in C. elegans, HTP-3, HIM-3, HTP-1 and HTP-2, making it difficult to identify what regions of these proteins are required to interact with PCH-2. Genetic mutations, combined with cytological analysis, seems the most straightforward way, at least in C. elegans, to understand whether and how PCH-2 and meiotic HORMADs interact to regulate meiotic pairing, synapsis and recombination.

Materials and Methods

Genetics and worm strains

The C. elegans Bristol N2 [78] was used as the wild-type strain. All strains were maintained at 20°C under standard conditions unless otherwise stated. Mutations and rearrangements used were as follows:

LG I: cmt-1(ok2879)

LG II: pch-2(blt5), meIs8 [Ppie-1::GFP::cosa-1 + unc-119(+)]

LG IV: spo-11(ok79), nT1[unc-?(n754) let-?(m435)] (IV, V), nTI [qIs51]

LG V: syp-1(me17), bcIs39 [lim-7p::ced-1::GFP + lin-15(+)]

The pch-2(blt5) allele, referred to as pch-2E253Q, was created by CRISPR-mediated genomic editing as described in [51, 52]. pDD162 was mutagenized using Q5 mutagenesis (New England Biolabs) and oligos GTTTTTGTTCTTATCGACGGTTTTAGAGCTAGAAATAGCAAGT and CAAGACATCTCGCAATAGG. The resulting plasmid was sequenced and two different correct clones (50ng/ul total) were mixed with pRF4 (100ng/ul) and the repair oligo CTCGTTCAAAAAATGTTCGATCAAATTGATGAACTAGCTGAAGATGAGAAGTGCATGGTTTTTGTGCTCATCGACCAAGTTTGATTTTTTTAAAAAACAATTTTTCTGGTTTTCATCAGTTTTTATGTCAGGTTGAAT (30ng/ul). Wildtype worms were picked as L4s, allowed to age 15–20 hours at 20°C and injected with the described mix. Worms that produced rolling progeny were identified and F1 rollers, as well as their wildtype siblings, were placed on plates seeded with OP50, 1–2 rollers per plate and 6–8 non-rolling siblings per plate, and allowed to produce progeny. PCR and Bsp1286I digestions were performed on these F1s to identify worms that contained the mutant allele and individual F2s were picked to identify mutant homozygotes. Multiple homozygotes carrying the pch-2(blt5) mutant allele were backcrossed against wildtype worms at least three times and analyzed to determine whether they produced the same mutant phenotype.

Antibodies, Immunostaining and Microscopy

DAPI staining and immunostaining was performed as in [64] 20 to 24 hours post L4 stage. Primary antibodies were as follows (dilutions are indicated in parentheses): rabbit anti-PCH-2 (1∶500) [50], rabbit anti-SYP-1 (1:500) [6], chicken anti-HTP-3 (1:250) [54], guinea pig anti-HTP-3 (1:250) [54], rabbit anti-ZIM-1 (1:1000), guinea pig anti-ZIM-2 (1:2500) [56], guinea pig anti-HIM-8 (1:250) [55], mouse anti-GFP (1:100) (Invitrogen), guinea pig anti-DSB-1 (1:500) [60] and rabbit anti-RAD-51 (1:1000) (Novus Biologicals). Secondary antibodies were Cy3 anti-rabbit, anti-guinea pig and anti-chicken (Jackson Immunochemicals) and Alexa-Fluor 488 anti-guinea pig and anti-rabbit (Invitrogen). All secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:500.

All images were acquired using a DeltaVision Personal DV system (Applied Precision) equipped with a 100X N.A. 1.40 oil-immersion objective (Olympus), resulting in an effective XY pixel spacing of 0.064 or 0.040 μm. Three-dimensional image stacks were collected at 0.2-μm Z-spacing and processed by constrained, iterative deconvolution. Image scaling and analysis were performed using functions in the softWoRx software package. Projections were calculated by a maximum intensity algorithm. Composite images were assembled and some false coloring was performed with Adobe Photoshop.

Scoring of germline apoptosis was performed as previously described in [64] in strains containing bcIs39 [lim-7p::ced-1::GFP + lin-15(+)] with the following exceptions. L4 hermaphrodites were allowed to age for 22 hours. They were then mounted under coverslips on 1.5% agarose pads containing 0.2mM levamisole and scored. A minimum of twenty-five germlines was analyzed for each genotype.

Quantification of pairing, synapsis, RAD-51 foci, GFP::COSA-1 foci, and DSB-1 positive nuclei was performed on animals 24 hours post L4 stage and with a minimum of three germlines per genotype. Relevant statistical analysis, as indicated in the Figure Legends, was used to assess significance. The number of nuclei assayed for each genotype for all figures is shown in S1 Table.

Supporting information

A. Images of meiotic nuclei stained with antibodies against HTP-3, SYP-1 and ZIM-2 in wildtype animals, pch-2E253Q and cmt-1 mutants. Circled nuclei have undergone non-homologous synapsis. B. Quantification of non-homologous synapsis wildtype animals, pch-2E253Q and cmt-1 mutants. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed Fisher exact tests. A *** indicates a p value < 0.0001.

(TIF)

A. Whole germline images of DSB-1 and DAPI staining in a wildtype, pch-2E253Q and cmt-1 mutant germline. Scale bar indicates 20 microns. B. Quantification of percentage of DSB-1-positive nuclei in wildtype, pch-2E253Q and cmt-1 mutant germlines. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed t-tests. A * indicates a p value < 0.05 and an n.s. indicates not significant.

(TIF)

A. Timecourse of the average number of RAD-51 foci per nucleus in wildtype and cmt-1 mutant germlines. Error bars indicate 2XSEM. B. Percentage of nuclei with five GFP::COSA-1 foci in wildtype animals, cmt-1 single and cmt-1;pch-2E253Q double mutants. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. Significance was assessed by performing two-tailed Fisher exact tests. A *** indicates a p value < 0.0001.

(TIF)

A. Whole germline images. Scale bar indicates 20 microns. B. Meiotic nuclei in mid-pachytene. C. Meiotic nuclei in late pachytene.

(TIF)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Arshad Desai, Karen Oegema, Abby Dernburg, and Anne Villeneuve for valuable strains and reagents.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the NIH (grant numbers R25GM104552 [D.V.] and R01GM097144 [N.B.]). Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Bhalla N, Dernburg AF. Prelude to a division. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:397–424. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borner GV, Kleckner N, Hunter N. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell. 2004;117(1):29–45. 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00292-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colaiacovo MP, MacQueen AJ, Martinez-Perez E, McDonald K, Adamo A, La Volpe A, et al. Synaptonemal complex assembly in C. elegans is dispensable for loading strand-exchange proteins but critical for proper completion of recombination. Dev Cell. 2003;5(3):463–74. 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00232-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Vries FA, de Boer E, van den Bosch M, Baarends WM, Ooms M, Yuan L, et al. Mouse Sycp1 functions in synaptonemal complex assembly, meiotic recombination, and XY body formation. Genes Dev. 2005;19(11):1376–89. 10.1101/gad.329705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JD, Sanchez-Moran E, Armstrong SJ, Jones GH, Franklin FC. The Arabidopsis synaptonemal complex protein ZYP1 is required for chromosome synapsis and normal fidelity of crossing over. Genes Dev. 2005;19(20):2488–500. 10.1101/gad.354705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacQueen AJ, Colaiacovo MP, McDonald K, Villeneuve AM. Synapsis-dependent and -independent mechanisms stabilize homolog pairing during meiotic prophase in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16(18):2428–42. 10.1101/gad.1011602 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page SL, Hawley RS. c(3)G encodes a Drosophila synaptonemal complex protein. Genes Dev. 2001;15(23):3130–43. 10.1101/gad.935001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sym M, Engebrecht JA, Roeder GS. ZIP1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1993;72(3):365–78. 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90114-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baudat F, Manova K, Yuen JP, Jasin M, Keeney S. Chromosome synapsis defects and sexually dimorphic meiotic progression in mice lacking Spo11. Mol Cell. 2000;6(5):989–98. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00098-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerton JL, DeRisi JL. Mnd1p: an evolutionarily conserved protein required for meiotic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(10):6895–900. 10.1073/pnas.102167899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ku JC, Ronceret A, Golubovskaya I, Lee DH, Wang C, Timofejeva L, et al. Dynamic localization of SPO11-1 and conformational changes of meiotic axial elements during recombination initiation of maize meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2020;16(4):e1007881 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007881 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leu JY, Chua PR, Roeder GS. The meiosis-specific Hop2 protein of S. cerevisiae ensures synapsis between homologous chromosomes. Cell. 1998;94(3):375–86. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81480-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petukhova GV, Romanienko PJ, Camerini-Otero RD. The Hop2 protein has a direct role in promoting interhomolog interactions during mouse meiosis. Dev Cell. 2003;5(6):927–36. 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00369-1 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romanienko PJ, Camerini-Otero RD. The mouse Spo11 gene is required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Mol Cell. 2000;6(5):975–87. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00097-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsubouchi H, Roeder GS. The Mnd1 protein forms a complex with hop2 to promote homologous chromosome pairing and meiotic double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22(9):3078–88. 10.1128/mcb.22.9.3078-3088.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsubouchi H, Roeder GS. The importance of genetic recombination for fidelity of chromosome pairing in meiosis. Dev Cell. 2003;5(6):915–25. 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00357-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida K, Kondoh G, Matsuda Y, Habu T, Nishimune Y, Morita T. The mouse RecA-like gene Dmc1 is required for homologous chromosome synapsis during meiosis. Mol Cell. 1998;1(5):707–18. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80070-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dernburg AF, McDonald K, Moulder G, Barstead R, Dresser M, Villeneuve AM. Meiotic recombination in C. elegans initiates by a conserved mechanism and is dispensable for homologous chromosome synapsis. Cell. 1998;94(3):387–98. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81481-6 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKim KS, Green-Marroquin BL, Sekelsky JJ, Chin G, Steinberg C, Khodosh R, et al. Meiotic synapsis in the absence of recombination. Science. 1998;279(5352):876–8. 10.1126/science.279.5352.876 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Couteau F, Nabeshima K, Villeneuve A, Zetka M. A component of C. elegans meiotic chromosome axes at the interface of homolog alignment, synapsis, nuclear reorganization, and recombination. Curr Biol. 2004;14(7):585–92. 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.033 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couteau F, Zetka M. HTP-1 coordinates synaptonemal complex assembly with homolog alignment during meiosis in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2005;19(22):2744–56. 10.1101/gad.1348205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martinez-Perez E, Villeneuve AM. HTP-1-dependent constraints coordinate homolog pairing and synapsis and promote chiasma formation during C. elegans meiosis. Genes Dev. 2005;19(22):2727–43. 10.1101/gad.1338505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva N, Ferrandiz N, Barroso C, Tognetti S, Lightfoot J, Telecan O, et al. The fidelity of synaptonemal complex assembly is regulated by a signaling mechanism that controls early meiotic progression. Dev Cell. 2014;31(4):503–11. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.10.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labrador L, Barroso C, Lightfoot J, Muller-Reichert T, Flibotte S, Taylor J, et al. Chromosome movements promoted by the mitochondrial protein SPD-3 are required for homology search during Caenorhabditis elegans meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(5):e1003497 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penkner A, Tang L, Novatchkova M, Ladurner M, Fridkin A, Gruenbaum Y, et al. The nuclear envelope protein Matefin/SUN-1 is required for homologous pairing in C. elegans meiosis. Dev Cell. 2007;12(6):873–85. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.05.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatkevich T, Boudreau V, Rubin T, Maddox PS, Huynh JR, Sekelsky J. Centromeric SMC1 promotes centromere clustering and stabilizes meiotic homolog pairing. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(10):e1008412 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dombecki CR, Chiang AC, Kang HJ, Bilgir C, Stefanski NA, Neva BJ, et al. The chromodomain protein MRG-1 facilitates SC-independent homologous pairing during meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Cell. 2011;21(6):1092–103. 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.09.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Borner GV, Barot A, Kleckner N. Yeast Pch2 promotes domainal axis organization, timely recombination progression, and arrest of defective recombinosomes during meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(9):3327–32. 10.1073/pnas.0711864105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C, Jomaa A, Ortega J, Alani EE. Pch2 is a hexameric ring ATPase that remodels the chromosome axis protein Hop1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(1):E44–53. 10.1073/pnas.1310755111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joshi N, Barot A, Jamison C, Borner GV. Pch2 links chromosome axis remodeling at future crossover sites and crossover distribution during yeast meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(7):e1000557 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lambing C, Osman K, Nuntasoontorn K, West A, Higgins JD, Copenhaver GP, et al. Arabidopsis PCH2 Mediates Meiotic Chromosome Remodeling and Maturation of Crossovers. PLoS Genet. 2015;11(7):e1005372 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wojtasz L, Daniel K, Roig I, Bolcun-Filas E, Xu H, Boonsanay V, et al. Mouse HORMAD1 and HORMAD2, two conserved meiotic chromosomal proteins, are depleted from synapsed chromosome axes with the help of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(10):e1000702 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bohr T, Ashley G, Eggleston E, Firestone K, Bhalla N. Synaptonemal Complex Components Are Required for Meiotic Checkpoint Function in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2016;204(3):987–97. 10.1534/genetics.116.191494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Daniel K, Lange J, Hached K, Fu J, Anastassiadis K, Roig I, et al. Meiotic homologue alignment and its quality surveillance are controlled by mouse HORMAD1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(5):599–610. 10.1038/ncb2213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goodyer W, Kaitna S, Couteau F, Ward JD, Boulton SJ, Zetka M. HTP-3 links DSB formation with homolog pairing and crossing over during C. elegans meiosis. Dev Cell. 2008;14(2):263–74. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hollingsworth NM, Goetsch L, Byers B. The HOP1 gene encodes a meiosis-specific component of yeast chromosomes. Cell. 1990;61(1):73–84. 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90216-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanchez-Moran E, Santos JL, Jones GH, Franklin FC. ASY1 mediates AtDMC1-dependent interhomolog recombination during meiosis in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2007;21(17):2220–33. 10.1101/gad.439007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shin YH, Choi Y, Erdin SU, Yatsenko SA, Kloc M, Yang F, et al. Hormad1 mutation disrupts synaptonemal complex formation, recombination, and chromosome segregation in mammalian meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(11):e1001190 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shin YH, McGuire MM, Rajkovic A. Mouse HORMAD1 is a meiosis i checkpoint protein that modulates DNA double- strand break repair during female meiosis. Biol Reprod. 2013;89(2):29 10.1095/biolreprod.112.106773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wojtasz L, Cloutier JM, Baumann M, Daniel K, Varga J, Fu J, et al. Meiotic DNA double-strand breaks and chromosome asynapsis in mice are monitored by distinct HORMAD2-independent and -dependent mechanisms. Genes Dev. 2012;26(9):958–73. 10.1101/gad.187559.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zetka MC, Kawasaki I, Strome S, Muller F. Synapsis and chiasma formation in Caenorhabditis elegans require HIM-3, a meiotic chromosome core component that functions in chromosome segregation. Genes Dev. 1999;13(17):2258–70. 10.1101/gad.13.17.2258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The HORMA domain: a common structural denominator in mitotic checkpoints, chromosome synapsis and DNA repair. Trends Biochem Sci. 1998;23(8):284–6. 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01257-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosenberg SC, Corbett KD. The multifaceted roles of the HORMA domain in cellular signaling. J Cell Biol. 2015;211(4):745–55. 10.1083/jcb.201509076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vader G. Pch2(TRIP13): controlling cell division through regulation of HORMA domains. Chromosoma. 2015;124(3):333–9. 10.1007/s00412-015-0516-y . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim Y, Rosenberg SC, Kugel CL, Kostow N, Rog O, Davydov V, et al. The chromosome axis controls meiotic events through a hierarchical assembly of HORMA domain proteins. Dev Cell. 2014;31(4):487–502. 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.09.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.West AMV, Komives EA, Corbett KD. Conformational dynamics of the Hop1 HORMA domain reveal a common mechanism with the spindle checkpoint protein Mad2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017. 10.1093/nar/gkx1196 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Medhi D, Goldman AS, Lichten M. Local chromosome context is a major determinant of crossover pathway biochemistry during budding yeast meiosis. Elife. 2016;5 10.7554/eLife.19669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shodhan A, Medhi D, Lichten M. Noncanonical Contributions of MutLgamma to VDE-Initiated Crossovers During Saccharomyces cerevisiae Meiosis. G3 (Bethesda). 2019;9(5):1647–54. 10.1534/g3.119.400150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zanders S, Sonntag Brown M, Chen C, Alani E. Pch2 modulates chromatid partner choice during meiotic double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2011;188(3):511–21. 10.1534/genetics.111.129031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deshong AJ, Ye AL, Lamelza P, Bhalla N. A quality control mechanism coordinates meiotic prophase events to promote crossover assurance. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(4):e1004291 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dickinson DJ, Ward JD, Reiner DJ, Goldstein B. Engineering the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using Cas9-triggered homologous recombination. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):1028–34. 10.1038/nmeth.2641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paix A, Wang Y, Smith HE, Lee CY, Calidas D, Lu T, et al. Scalable and versatile genome editing using linear DNAs with microhomology to Cas9 Sites in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 2014;198(4):1347–56. 10.1534/genetics.114.170423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye Q, Rosenberg SC, Moeller A, Speir JA, Su TY, Corbett KD. TRIP13 is a protein-remodeling AAA+ ATPase that catalyzes MAD2 conformation switching. eLife. 2015;4 Epub 2015/04/29. 10.7554/eLife.07367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.MacQueen AJ, Phillips CM, Bhalla N, Weiser P, Villeneuve AM, Dernburg AF. Chromosome sites play dual roles to establish homologous synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Cell. 2005;123(6):1037–50. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phillips CM, Wong C, Bhalla N, Carlton PM, Weiser P, Meneely PM, et al. HIM-8 binds to the X chromosome pairing center and mediates chromosome-specific meiotic synapsis. Cell. 2005;123(6):1051–63. 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips CM, Dernburg AF. A family of zinc-finger proteins is required for chromosome-specific pairing and synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Dev Cell. 2006;11(6):817–29. 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alpi A, Pasierbek P, Gartner A, Loidl J. Genetic and cytological characterization of the recombination protein RAD-51 in Caenorhabditis elegans. Chromosoma. 2003;112(1):6–16. 10.1007/s00412-003-0237-5 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yokoo R, Zawadzki KA, Nabeshima K, Drake M, Arur S, Villeneuve AM. COSA-1 reveals robust homeostasis and separable licensing and reinforcement steps governing meiotic crossovers. Cell. 2012;149(1):75–87. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rosu S, Zawadzki KA, Stamper EL, Libuda DE, Reese AL, Dernburg AF, et al. The C. elegans DSB-2 protein reveals a regulatory network that controls competence for meiotic DSB formation and promotes crossover assurance. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003674 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stamper EL, Rodenbusch SE, Rosu S, Ahringer J, Villeneuve AM, Dernburg AF. Identification of DSB-1, a protein required for initiation of meiotic recombination in Caenorhabditis elegans, illuminates a crossover assurance checkpoint. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003679 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alfieri C, Chang L, Barford D. Mechanism for remodelling of the cell cycle checkpoint protein MAD2 by the ATPase TRIP13. Nature. 2018;559(7713):274–8. 10.1038/s41586-018-0281-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brulotte ML, Jeong BC, Li F, Li B, Yu EB, Wu Q, et al. Mechanistic insight into TRIP13-catalyzed Mad2 structural transition and spindle checkpoint silencing. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1956 10.1038/s41467-017-02012-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ji J, Tang D, Shen Y, Xue Z, Wang H, Shi W, et al. P31comet, a member of the synaptonemal complex, participates in meiotic DSB formation in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(38):10577–82. 10.1073/pnas.1607334113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bhalla N, Dernburg AF. A conserved checkpoint monitors meiotic chromosome synapsis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2005;310(5754):1683–6. 10.1126/science.1117468 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bohr T, Nelson CR, Klee E, Bhalla N. Spindle assembly checkpoint proteins regulate and monitor meiotic synapsis in C. elegans. J Cell Biol. 2015;211(2):233–42. 10.1083/jcb.201409035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson CR, Hwang T, Chen PH, Bhalla N. TRIP13PCH-2 promotes Mad2 localization to unattached kinetochores in the spindle checkpoint response. J Cell Biol. 2015;211(3):503–16. 10.1083/jcb.201505114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ma HT, Poon RY. TRIP13 Regulates Both the Activation and Inactivation of the Spindle-Assembly Checkpoint. Cell Rep. 2016;14(5):1086–99. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ma HT, Poon RYC. TRIP13 Functions in the Establishment of the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint by Replenishing O-MAD2. Cell Rep. 2018;22(6):1439–50. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.01.027 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Joyce EF, McKim KS. Chromosome axis defects induce a checkpoint-mediated delay and interchromosomal effect on crossing over during Drosophila meiosis. PLoS Genet. 2010;6(8). 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rosu S, Libuda DE, Villeneuve AM. Robust crossover assurance and regulated interhomolog access maintain meiotic crossover number. Science. 2011;334(6060):1286–9. 10.1126/science.1212424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miniowitz-Shemtov S, Eytan E, Kaisari S, Sitry-Shevah D, Hershko A. Mode of interaction of TRIP13 AAA-ATPase with the Mad2-binding protein p31comet and with mitotic checkpoint complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(37):11536–40. 10.1073/pnas.1515358112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.San-Segundo PA, Roeder GS. Pch2 links chromatin silencing to meiotic checkpoint control. Cell. 1999;97(3):313–24. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80741-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van Hooff JJ, Tromer E, van Wijk LM, Snel B, Kops GJ. Evolutionary dynamics of the kinetochore network in eukaryotes as revealed by comparative genomics. EMBO Rep. 2017. 10.15252/embr.201744102 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vleugel M, Hoogendoorn E, Snel B, Kops GJ. Evolution and function of the mitotic checkpoint. Dev Cell. 2012;23(2):239–50. 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.06.013 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tromer EC, van Hooff JJE, Kops G, Snel B. Mosaic origin of the eukaryotic kinetochore. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(26):12873–82. 10.1073/pnas.1821945116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ye Q, Lau RK, Mathews IT, Birkholz EA, Watrous JD, Azimi CS, et al. HORMA Domain Proteins and a Trip13-like ATPase Regulate Bacterial cGAS-like Enzymes to Mediate Bacteriophage Immunity. Mol Cell. 2020;77(4):709–22 e7. 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Burroughs AM, Zhang D, Schaffer DE, Iyer LM, Aravind L. Comparative genomic analyses reveal a vast, novel network of nucleotide-centric systems in biological conflicts, immunity and signaling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(22):10633–54. 10.1093/nar/gkv1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brenner S. The genetics of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1974;77(1):71–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]