Abstract

Background:

Successful management of patients reporting with extreme sensitivity in second molar after surgical extraction of deeply impacted mandibular third molar poses a big challenge to oral surgeons and periodontists worldwide. A variety of grafts, barrier membranes, and guided tissue regeneration techniques have been used postsurgically for soft- and hard-tissue formation. In the current study, platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), a second-generation platelet aggregate, was assessed for its effectiveness in promoting hard- and soft-tissue healing.

Objective:

The aim of the study was to evaluate the efficacy of PRF in hard- and soft-tissue healing after extraction of mandibular third molar.

Materials and Methods:

Bilateral surgical disimpaction of mandibular third molar was done on 25 patients. In every patient, randomly allocated test side received PRF and the other side acted as control. Pain, edema, tenderness, sensitivity, Sulcus Bleeding Index (SBI), Plaque Index, clinical attachment level (CAL), probing depth, and bone height were measured at different intervals for a maximum period of 6 months.

Results:

There was a statistically significant improvement in patients' signs and symptoms of pain, tenderness, edema, and sensitivity with the use of PRF. A statistically significant improvement was seen in SBI, Plaque Index, and probing depths, while CALs and bone height were not influenced by PRF use.

Conclusion:

PRF is a very viable and useful biomaterial for soft-tissue healing and relieving patient symptoms, however, it does not help in hard-tissue healing with respect to cortical bone.

Keywords: Platelet-rich fibrin, socket healing, third molar

INTRODUCTION

The extraction of deeply impacted mandibular third molars may cause significant defects at the distal root of mandibular second molar. Post extraction, many patients report with extreme sensitivity in the area, which is attributed to cemental exposure of the distal root of second molar. Pain, trismus, swelling, dysphagia, pyrexia, and inability to do routine work are among the other common problems faced by patients after extraction of third molar teeth.[1] After extraction, local periodontal defects such as increased probing depth, gingival recession, bleeding, and suppuration on probing have been frequently reported to be associated with second mandibular molar tooth.[2] Such a condition can be very disturbing to the patient, hampering with regular activities of eating and drinking and leading to a reduced quality of life.

Over decades, various materials have been used postsurgically for hard- and soft-tissue healing: biomaterials such as autogenous grafts, allografts, and xenografts; synthetic materials such as alloplasts;[3] and guided tissue regeneration membranes.[4]

Platelet-rich fibrin (PRF), a second-generation platelet aggregate,[5] has been widely used to accelerate soft- and hard-tissue healing because of the presence of various growth factors (GFs). In-vitro studies have shown PRF to induce a significant, continuous stimulation and proliferation of all cell types with a strong and highly significant differentiation of osteoblasts.[6] Viable platelets in PRF have shown to release six GFs, that is, platelet-derived growth factor-AB (PDGF-AB), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1), insulin-like GF, epithelial growth factor, and recombinant human basic fibroblast GF, of which TGF-β1, PDGF-AB, and VEGF are the three main GFs released in high quantity.[7]

Thus, the current prospective study was aimed at investigating the clinical and radiological effectiveness of PRF in hard (bone)- and soft (gingiva)-tissue healing in defect created distal to the mandibular second molar following trans-alveolar extraction of third molar.

Objective

The objective was to determine the efficacy of PRF in hard- and soft-tissue healing after extraction of a mandibular third molar tooth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted in the departments of oral and maxillofacial surgery and periodontology. Patients requiring bilateral mandibular third molar extraction were recruited and randomly assigned for the use of PRF on one side and no use of PRF on the other side. Ethical clearance was taken from the institutional ethical clearance committee. Patients were explained about the study prior to the surgery and a signed informed consent was taken. The study was conducted over a period of 8 months, from November 01, 2018, to July 31, 2019, wherein all the surgical procedures were performed in the first 2 months.

Study sample

A total of 25 patients (14 males and 11 females) reported in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery fulfilling the inclusion criteria in the study period constituted the study sample. The sample age ranged from 18 to 55 years, with a mean age of 32.3 years.

Inclusion criteria

Patients ≥18 years of age requiring bilateral extraction of mandibular third molar with no gender bias

Patients reporting with pain, edema, or sensitivity in the region of mandibular third molar. In the case of pericoronitis, an antibiotic course of 3 days was given prior to extraction to facilitate mouth opening

Patients with bilateral impacted mandibular third molars leading to radiographic bone loss of >3 mm distal to the second molar irrespective of the type of third molar impaction.

Exclusion criteria

Medically compromised and pregnant patients

Patients with abnormal platelet counts (< 200,000/mm3)

Patients with missing second molars

Patients with smoking and tobacco habits

Patients on medications that may interfere with wound healing such as anticoagulants, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive agents.

Preoperative procedures and assessment

Each patient was allotted a unique code number for the maintenance of records and easy future referral. One week prior to the surgery, the patients underwent oral prophylaxis by a co-investigator (CI) 1 and assessed on four periodontal parameters, namely Plaque Index, Sulcus Bleeding Index (SBI), clinical attachment level (CAL), and probing depth. SBI was scored on a scale of 0–5 in whole numbers.[8] CAL and probing depths were measured in millimeters (mm) using a periodontal probe.

All pre- and post-operative intraoral periapical radiographs (IOPARs) were shot by paralleling technique[9] using an Intraskan DC (Wallmount, Skanray Technologies Pvt. Ltd.), with parameters of 70 kVp, 8 mA, and 125 ms, on a film with grid for easy measurement of bone height. Bone height was measured from the crest of the interdental bone between the second and third molars to the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of the second molar.

Intraoperative

Bilateral single-stage surgical disimpactions were done by PI 1 under local anesthesia. Each patient acted as his/her own control. PRF was placed on the test side and the other side acted as a control. Side selection was based on randomization done by PI 2 to decide the test and control sides and was kept confidential. Placing of PRF (only on test side) and suturing the bilateral surgical sites using 3-0 Mersilk suture was done by PI 2. No complications were encountered during the conduction of surgical procedure.

Preparation of platelet-rich fibrin

PRF preparation was done in the time frame between the completion of bilateral extractions and hemostasis. In this time, patients' intravenous blood was collected in a 10-ml Vacutainer tube without anticoagulant and immediately centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min to prepare fresh autologous PRF.[10] PRF thus formed was separated from platelet-poor plasma and red blood cells to be placed at the test side.

Postoperative assessment

Immediate postoperative radiographs of both sides were taken to assess the bone loss distal to the second molars. Bone height was assessed radiographically on an on both sides. Bone height was measured from the crest of the interdental bone between the second and third molars to the CEJ of the second molar.

Each patient was followed up for a total duration of 6 months. Patients were assessed on four surgical (pain, tenderness, sensitivity, and edema) and four periodontal (Plaque Index, SBI, CAL, and probing depth) parameters along with bone height levels on control as well as test sides at various fixed intervals. Surgical parameters were checked by PI 1, whereas periodontal parameters and bone height were assessed by CI 1.

Pain, tenderness, and edema were checked on day 1 and day 3 and after 1 week and 1 month, respectively. Sensitivity in response to cold, air spray, and probing was assessed after 1 week and 1, 3, and 6 months. Pain and tenderness were determined on a Visual Analog Scale[11] combined with pain drawings[11] for better understanding and acknowledgment by the patient. Sensitivity and edema were given a score of 0, 1, 2, or 3 depending on patient reporting and findings [Table 1]. Area-specific SBI and Plaque Index were recorded after 1 week and 1, 3, and 6 months. Area-specific CAL, probing depth, and radiographic bone height were checked after 3 and 6 months.

Table 1.

Scoring criteria for edema and sensitivity

| Score | Parameter | |

|---|---|---|

| Edema | Sensitivity | |

| 0 | No edema | Negative response to all the three stimuli |

| 1 | Either intraoral or extraoral edema | Positive response to any one of the three stimuli |

| 2 | Both intraoral and extraoral edema | Positive response to any two of the three stimuli |

| 3 | N/A | Positive response to all the three stimuli |

N/A=Not applicable

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). To make a comparison between the two groups, independent t-test was used for normally distributed data and Mann–Whitney U-test was used for nonnormally distributed data. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

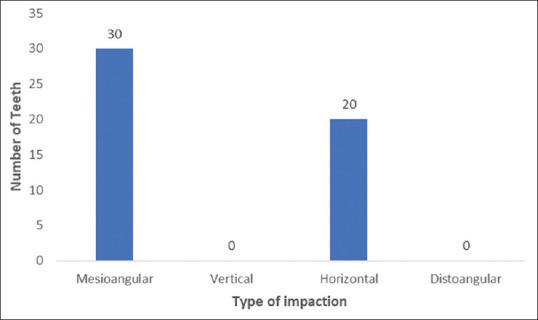

A total of 50 transalveolar extractions were done in 25 patients. Among all the extracted impacted third molars, the tooth either had horizontal or mesioangular impaction [Figure 1]. No other type of impaction was found.

Figure 1.

Distribution of encountered impactions of extracted mandibular third molars

There was a statistically significant difference in the intensity of pain on the control and test sides on day 1 (P < 0.001) with a mean value of 2.08 ± 1.352 on the control side compared to 0.80 ± 0.764 on the test side. Pain decreased on control as well as test sides from day 1 to day 3 with a rise in pain at week 1 and subsequently to no pain after 1 month; however, the values on the test side were always less than those on the control side [Table 2]. A similar trend of decrease followed by increase to finally 0 was seen with tenderness on control as well as test sides, again values always being less for the test side compared to the control side [Table 2].

Table 2.

Pain and tenderness assessment on control and test sides

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Week 1 | 1 month | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Tenderness | Pain | Tenderness | Pain | Tenderness | Pain | Tenderness | |||||||||

| Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | |

| Control group | 2.08±1.352 | <0.001 | 2.08±1.352 | <0.001 | 1.80±1.041 | <0.001 | 1.80±1.041 | <0.001 | 4.48±1.584 | 0.005 | 4.48±1.584 | 0.002 | 0 | N/A | 0 | N/A |

| Test group | 0.80±0.764 | 0.80±0.764 | 0.56±0.712 | 0.56±0.712 | 3.24±1.422 | 3.16±1.313 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

N/A=Not available

Edema was 0.24 ± 0.597 after 1 week on the test side as compared to day 1 (0.72 ± 0.792) showing significant improvement, whereas the values did not show much improvement in edema on the control side from day 1 (1.88 ± 0.332) to week 1 (1.28 ± 0.792). Edema was always statistically significantly less (P < 0.001) on the test side compared to that of the control side. In both cases, no edema was observed after 1 month [Table 3].

Table 3.

Assessment of edema and sensitivity on control and test sides

| Edema | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Day 3 | Week 1 | 1 month | |||||

| Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | |

| Control group | 1.88±0332 | <0.001 | 1.60±0.500 | <0.001 | 1.28±0.792 | <0.001 | 0 | N/A |

| Test group | 0.72±0792 | 0.40±0.764 | 0.24±0.597 | 0 | ||||

| Sensitivity | ||||||||

| Week 1 | After 1 month | After 3 months | After 6 months | |||||

| Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | |

| Control group | 2.40±0.577 | <0.001 | 2.40±0.500 | 0.192 | 1.40±0.577 | <0.001 | 1.32±0.748 | <0.001 |

| Test group | 0.64±0.757 | 2.64±0.757 | 0.48±0.586 | 0.32±0.476 | ||||

N/A=Not available

Week 1 to Month 1 saw no increase in sensitivity on the control side with an opposite trend on the test side. However, from 1 month onward, there was a gradual decrease in sensitivity on both sides, with a statistically significant difference in values (P < 0.001), being always less for the test side [Table 3].

No statistically significant difference was seen in the context to SBI on control and test sides (P = 0.009), with results shifting to statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) on both the sides after 3 and 6 months, with values being lesser for the test side compared to that of the control side [Table 4]. Plaque Index showed improved and better results on the test side compared to the control side, with a statistically significant difference in values (P < 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Sulcus Bleeding Index and Plaque Index findings on control and test sides

| SBI | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pretreatment | After 1 month | After 3 months | After 6 months | |||||||

| Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | |||

| Control group | 0 | N/A | 1.1764±0.54582 | 0.009 | 1.1528±0.31089 | <0.001 | 1.1864±0.50278 | <0.001 | ||

| Test group | 0 | 0.7660±0.51786 | 0.1528±0.31089 | 0.1732±0.37411 | ||||||

| Plaque Index | ||||||||||

| Pretreatment | Week 1 | After 1 month | After 3 months | After 6 months | ||||||

| Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | |

| Control group | 0 | N/A | 1.4264±0.71283 | <0.001 | 1.1528±0.31089 | <0.001 | 1.1864±0.50278 | <0.001 | 0.8200±0.53774 | <0.001 |

| Test group | 0 | 0.7660±0.51786 | 0.1528±0.31089 | 0.1732±0.37411 | 0.2200±0.41028 | |||||

SBI=Sulcus bleeding index, N/A=Not available

There was no statistically significant pretreatment discrepancy in CALs on both the sides (P = 0.763). An improvement in CALs was seen on the control side post extraction after 3 and 6 months, with a downward trend on the test side. A powerful improvement was seen on the control than the test side (P < 0.001) after 3 and 6 months [Table 5].

Table 5.

Clinical attachment levels on control and test sides

| Pretreatment | Month 3 | Month 6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean value | P | Mean value | P | Mean value | P | |

| Control group | 0.32±0.47610 | 0.763 | 2.16±0.62450 | <0.001 | 2.32±0.57518 | <0.001 |

| Test group | 0.28±0.45826 | 0.59±0.35998 | 0.59±0.35998 | |||

Improvement in probing depth was seen on both the sides from the preoperative phase to 3 months postoperatively with no statistically significant variation (P = 0.229). Post 6 months, the control group saw an increase in probing depth, whereas there was a further decrease in probing depth in the test group [Table 6].

Table 6.

Probing depth and bone height measurements on control and test sides

| Pretreatment | Month 3 | Month 6 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probing depth | Bone height | Probing depth | Bone height | Probing depth | Bone height | |||||||

| Mean value | P | Mean value (in mm) | P | Mean value | P | Mean value (in mm) | P | Mean value | P | Mean value (in mm) | P | |

| Control group | 1.41±0.57 | 0.585 | 2.84±0.85 | 0.863 | 0.83±0.55 | 0.229 | 2.24±0.83 | 0.188 | 0.97±0.47 | <0.001 | 1.76±0.83 | 0.164 |

| Test group | 1.32±0.63 | 2.88±0.78 | 0.65±0.49 | 1.92±0.86 | 0.38±0.44 | 1.44±0.77 | ||||||

Preoperatively, there was no statistically significant difference in bone heights on control and test sides (P = 0.863). Postoperatively, loss of bone height was seen on both control and test sides; however, bone height was always slightly more on the control side as compared to the test side with no significant difference in bone levels on both sides after 3 and 6 months [Table 6].

DISCUSSION

Platelet concentrates have been used since long to promote healing as they contain high quantities of GFs.[5] Leukocyte-poor or pure PRF is one of the two types of available PRF but has a difficult and time-consuming processing.[5] Leukocyte- and PRF (L-PRF), also known as Choukroun's PRF, is a second-generation platelet aggregate rich in leukocytes and PRF biomaterial,[5] which helps to promote healing due to the presence of numerous GFs.[7] In addition, L-PRF is easy to prepare, requiring lower cost with the use of no chemicals or unnatural conditions for its production.[5]

Previous studies have shown L-PRF to produce a significant reduction in the probing depth with increased bone levels post use of autogenous PRP.[12,13] Our results showed a similar trend in probing depth values with statistically significant difference in values on control and test sides, however no statistically significant improvement was seen in bone levels post use of PRF.

PRF significantly improved patients' symptoms of pain, tenderness, and edema immediate postoperatively, though an equal amount of time (1 month) was taken for the symptoms to subside on both the sides [Tables 2 and 3]. It has been shown that the effect of PRF in soft-tissue healing is due to its clinical potential to enhance angiogenesis, which aids in relieving the symptoms and improve healing.[14] Although it can be hypothesized based on the study by Asmael et al.[15] that PRF does not aid in preventing dry socket and reducing pain and closure of socket in smokers, it promotes the quality of healing seen in soft tissue. In the current study, there was a statistical reduction in pain values in the test side as compared to the control side. The probable cause for pain reduction with the use of PRF could be attributed to reduced inflammation and subsequent edema in the test side. The exact mechanism of pain reduction with the use of PRF would require further biochemical studies. Our results showed pain findings similar to a previous study of Uyanik et al., wherein PRF was used in combination with either traditional surgery or piezosurgery and showed a significant reduction in postoperative pain and trismus with a decreased requirement of consuming analgesics. Their findings showed no significant difference in postoperative swelling with or without the use of PRF.[16] In contrast to their results, our findings showed a significant reduction in postoperative swelling as well with the use of PRF. Dar et al.[17] conducted a similar study as ours comparing hard- and soft-tissue healing potential of PRF in mandibular third molar extraction socket in terms of pain, swelling, periodontal health, and bone healing. In contrast to our study with a follow-up period of 6 months, a postoperative clinical assessment was done for 3 months only by Dar et al. Similar to our findings, a significant improvement was seen in edema on test site compared to control side. They also commented on total bone density (lamina dura, density, and trabeculae pattern), showing a significant increase on the test side after 4 weeks with no further significant improvement at 12-week assessment. The study does not present findings in terms of probing depth, sensitivity, and periodontal indices.

Although sensitivity persisted on both sides 6 months postoperatively, an improvement was observed on the PRF side as compared to control. Mixed results were seen with the periodontal parameters. More improvement was seen in SBI, Plaque Index, and probing depths in the test group compared to the control group. Li et al.[18] in their study showed that PRF enhances osteogenic lineage differentiation of alveolar bone progenitors more than of periodontal progenitors by augmenting osteoblast differentiation, RUNX2 expression, and mineralized nodule formation via its principal component fibrin. They also documented that PRF functions as a complex regenerative scaffold promoting both tissue-specific alveolar bone augmentation and surrounding periodontal soft-tissue regeneration through progenitor-specific mechanisms. Contrary to their findings, our findings were similar to those observed by Srinivas et al.[19] who encountered significant enhancement in bone healing and density with the use of PRF with no statistically remarkable difference in the bone heights of the two groups. We also did not find a statistically significant difference in bone height gained on the two sides, although mean values of bone formation were higher for the control group than for the test group.

CONCLUSION

It was observed that PRF has no significant effect in enhancing healing of hard tissue (cortical bone formation) distal to mandibular second molar following transalveolar third molar extraction. Its probable effects on cancellous bone formation cannot be commented due to the limitation of histological examination in the current study. However, significant improvement in CALs and clinical periodontal indices warrants the use of PRF for soft-tissue healing and relief of clinical symptoms due to extraction wounds. The authors suggest conduction of future studies with larger sample size and histological examination of surgical site for better assessment of the role of PRF in hard-tissue healing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Gool AV, Ten Bosch JJ, Boering G. Clinical consequences of complaints and complications after removal of the mandibular third molar. Int J Oral Surg. 1977;6:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(77)80069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kan KW, Liu JK, Lo EC, Corbet EF, Leung WK. Residual periodontal defects distal to the mandibular second molar 6-36 months after impacted third molar extraction. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:1004–11. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.291105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodella LF, Favero G, Labanca M. Biomaterials in maxillofacial surgery: Membranes and grafts. Int J Biomed Sci. 2011;7:81–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karapataki S, Hugoson A, Kugelberg CF. Healing following GTR treatment of bone defects distal to mandibular 2nd molars after surgical removal of impacted 3rd molars. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:325–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027005325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: From pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF) Trends Biotechnol. 2009;27:158–67. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Diss A, Odin G, Doglioli P, Hippolyte MP, Charrier JB. In vitro effects of Choukroun's PRF (platelet-rich fibrin) on human gingival fibroblasts, dermal prekeratinocytes, preadipocytes, and maxillofacial osteoblasts in primary cultures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2009;108:341–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dohan Ehrenfest DM, de Peppo GM, Doglioli P, Sammartino G. Slow release of growth factors and thrombospondin-1 in Choukroun's platelet-rich fibrin (PRF): A gold standard to achieve for all surgical platelet concentrates technologies. Growth Factors. 2009;27:63–9. doi: 10.1080/08977190802636713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mühlemann HR, Son S. Gingival sulcus bleeding – A leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta. 1971;15:107–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shah N, Bansal N, Logani A. Recent advances in imaging technologies in dentistry. World J Radiol. 2014;6:794–807. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i10.794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pradeep AR, Rao NS, Agarwal E, Bajaj P, Kumari M, Naik SB. Comparative evaluation of autologous platelet-rich fibrin and platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of 3-wall intrabony defects in chronic periodontitis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1499–507. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(Suppl 1):S17–24. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1044-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sammartino G, Tia M, Marenzi G, di Lauro AE, D'Agostino E, Claudio PP. Use of autologous platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in periodontal defect treatment after extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:766–70. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonello Gde M, Torres do Couto R, Giongo CC, Corrêa MB, Chagas Júnior OL, Lemes CH. Evaluation of the effects of the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on alveolar bone repair following extraction of impacted third molars: Prospective study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41:e70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miron RJ, Fujioka-Kobayashi M, Bishara M, Zhang Y, Hernandez M, Choukroun J. Platelet-rich fibrin and soft tissue wound healing: A systematic review. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2017;23:83–99. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2016.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asmael HM, Jamil FA, Hasan AM. Novel application of platelet-rich fibrin as a wound healing enhancement in extraction sockets of patients who smoke. J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29:e794–7. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uyanık LO, Bilginaylar K, Etikan İ. Effects of platelet-rich fibrin and piezosurgery on impacted mandibular third molar surgery outcomes. Head Face Med. 2015;11:25. doi: 10.1186/s13005-015-0081-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dar MM, Shah AA, Najar AL, Younis M, Kapoor M, Dar JI. Healing potential of platelet rich fibrin in impacted mandibular third molar extraction sockets. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018;8:206–13. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_181_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Pan S, Dangaria SJ, Gopinathan G, Kolokythas A, Chu S, et al. Platelet-rich fibrin promotes periodontal regeneration and enhances alveolar bone augmentation. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:638043. doi: 10.1155/2013/638043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Srinivas B, Das P, Rana MM, Qureshi AQ, Vaidya KC, Ahmed Raziuddin SJ. Wound healing and bone regeneration in postextraction sockets with and without platelet-rich fibrin. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2018;8:28–34. doi: 10.4103/ams.ams_153_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]