Abstract

Background:

This report is an overview of results from the 2016 Finnish Gambling Harms Survey covering the population and clinical perspectives. It summarises the main findings on gambling participation, gambling habits, gambling-related harm, and opinions on gambling advertising.

Methods:

The population sample (n = 7186) was collected from three regions and the clinical sample (n = 119) in a gambling help clinic.

Results:

Frequency of gambling in the population sample was characteristically once a week, while in the clinical sample it was daily. Men gambled more often than women only in the population sample. The most common gambling environments were kiosks, grocery stores or supermarkets, and home. The most typical gambling-related harms were financial or emotional/psychological harms; the amount of experienced harm was considerable among the clinical sample. The clinical sample also perceived gambling advertising as obtrusive and as a driving force for gambling.

Conclusions:

The results of the clinical sample imply that when gambling gets out of hand, the distinctions between gamblers’ habits diminish and become more streamlined, focusing on gambling per se – doing it often, and in greater varieties (different game types). There is a heightened need to monitor gambling and gambling-related harm at the population level, especially amongst heavy consumers, in order to understand what type of external factors pertaining to policy and governance may contribute to the shift from recreational to problem gambling.

Keywords: client survey, disordered gambling, gambling, gambling-related harm, population survey, problem gambling

Gambling involves different types of harm, which materialise in various ways and affect individuals to different extents. Negative consequences of gambling include financial harm; relationship disruption, conflict, or breakdown; emotional or psychological harm, and decrements in health; cultural harm; reduced performance at work or in study; and criminal activity (Browne et al., 2016; Langham et al., 2016). Harm can affect the gamblers themselves, but also significant persons in the gamblers’ lives (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Browne et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Salonen, Alho, & Castrén, 2016).

Gambling-related harm has traditionally been studied primarily from the perspective of problem gambling prevalence and the factors influencing harmful gambling (Abbott et al., 2015; Salonen & Raisamo, 2015; Turja, Halme, Mervola, Järvinen-Tassopoulos, & Ronkainen, 2012; Williams, Volberg, & Stevens, 2012), but there is now an ongoing shift towards seeing the negative consequences of gambling in a more kaleidoscopic outlook as different kinds of entangled impacts on health and wellbeing. A wider problem taxonomy is evident in recent harm studies conducted in Australia and New Zealand (Browne, Bellringer et al., 2017; Browne, Greer, Rawat, & Rockloff, 2017; Browne, Rawat et al., 2017; Langham et al., 2016; Shannon, Anjoul, & Blaszczynski, 2017).

Gambling habits keep evolving; social contexts and gambling environments change. In Finland, where both land-based and online gambling is widely available, land-based gambling is a popular activity. It includes electronic gaming machines (EGMs) and is accessible both in casinos and casino-type environments and kiosks, restaurants, petrol stations, and shopping centres. To improve preventive work and harm reduction, there is a need for more knowledge on gambling habits and the ways in which gambling may be affected by marketing or different types of gambling advertising.

Until the end of 2016, Finnish gambling policy was based on a three-party monopoly system. In January 2017, the three operators were merged into a single company. The Finnish Gambling Harms Survey was launched to study gambling, gambling-related harm, and exposure to gambling marketing before and after the merger. This research report is an overview of the results of the first stage of the Gambling Harms Survey,1 which covers a broader range of dimensions of gambling participation, gambling habits, and gambling-related harm than any previous Nordic survey on gambling.

This report summarises selected results from the two reports of the Gambling Harms Survey, both published in December 2017 (Salonen, Castrén, Latvala, Heiskanen, & Alho, 2017; Salonen, Latvala, Castrén, Selin, & Hellman, 2017). What we do here is study and discuss (a) gambling participation (gambling frequency, game types, gambling mode, motivation); (b) gambling habits (gambling environments, social context); (c) gambling-related harm for both gamblers and concerned significant others (CSOs); and (d) an overall rating of gambling advertising and the impacts of advertising on gambling as a whole. Both population-based and clinical samples provide insight into the state of these dimensions in Finland in 2016. The results are given for the samples as a whole, but also for gender and age groups when relevant.

Material and methods

Population-based data

The first wave of a longitudinal population survey data was collected by Statistics Finland between 9 January and 26 May 2017. The results are drawn from both online and postal survey responses from people aged 18 years or over living in the regions of Uusimaa, Pirkanmaa, and Kymenlaakso. Participants were randomly selected from the population register. All in all, 7186 persons participated in the survey (response rate 36%), which was available in both official languages, Finnish and Swedish. The data were weighted on gender, age, and region of residence.

Clinical data

An online survey was conducted among 119 clients who had sought help for their own gambling problems at a gambling clinic specialising in gambling problems located in Helsinki. Cross-sectional and anonymous data were collected in collaboration with the clinic staff and Statistics Finland between 16 January and 30 April in 2017. The inclusion criteria required that the participants (1) were aware of the objectives of the study and of their rights, and, that they participated voluntarily in the study, (2) had sought help for their gambling problems, (3) were 18 years or over and, (4) were able to answer the questionnaire in Finnish or Swedish.

Measurements

Gambling participation

Gambling frequency during 2016 (no gambling, less than monthly, 1–3 times/month, once a week, several times a week) was inquired about separately for 18 predefined game types (Salonen & Raisamo, 2015; Turja et al., 2012). Overall gambling frequency was calculated from a gambler’s most active game type. A categorical variable with three options – online, land-based, online and land-based – helped us to determine the gambling mode. Gambling motivation was examined by asking the participants “What would you say is the main reason that you gamble?”, with seven response options (Williams, Pekow et al., 2017).

Gambling habits

Gambling habits were measured by categorical questions. Gambling context was evaluated by asking: “Think of the year 2016. Which of the following alternatives describe(s) most accurately your own gambling?”, while gambling environments were studied by asking the question: “What sort of environments did you gamble in during the year 2016?”

Gambling-related harm for the gambler

At-risk and problem gambling was assessed using the 14-item Problem and Pathological Gambling Measure (PPGM; Williams & Volberg, 2010). Furthermore, gambling-related harm was evaluated using a 72-item Harms Checklist (Browne et al., 2016; Langham et al., 2016) with six harm domains, and a dichotomous variable was created for each domain to indicate whether the respondent had experienced such harm.

Gambling-related harm for CSOs

Gambling-related harm for CSOs was evaluated by inquiring: “During 2016, has there been a person in your life that you consider gambles too much?” If the person responded yes, this was followed by the question “What is this person’s relationship to you?”, with 10 response options. A dichotomous variable was created to indicate whether the respondent had any close family/friends with gambling problems. Gambling-related harm for concerned significant others was inquired about giving 11 response options (Salonen et al., 2016). In addition, a new item, work and study-related harm, was added as well as an open-ended response option.

Gambling marketing

Gambling marketing of the Finnish monopoly companies was inquired about with two questions: “Continue to think about the year 2016. What do you think about the RAY’s, Veikkaus’ and Finntoto’s advertising in Finland?”, and “How has the advertising by these gambling operators affected you?”

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS 24.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance (p) was determined to detect statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) using one-way ANOVA and t-tests. Detailed descriptive statistics and the exact p-values are presented in the original reports (Salonen, Castrén et al., 2017; Salonen, Latvala et al., 2017).

Results

Participants

Men made up 48% of the population sample, and the respondents’ average age was 49 years (SD = 18.4), whereas the clinical sample included 71% men, and the average age was 37 years (SD = 14.1).

Gambling participation

Most respondents (83%) in the population sample had gambled on at least one game type during 2016 (79% of women, 87% of men), typically weekly lottery games (72%) and scratch cards (50%). Electronic gaming machines were also moderately popular among the game types that can be accessed in places other than casino venues (32%). Electronic gaming machines are typically found in grocery stores, kiosks, or petrol stations. Equally popular (32%) were low-paced daily lottery games. A significant amount of gambling also occurred on the popular cruising lines operating between Finland and Sweden and Estonia: 16% of all respondents in the population sample had gambled on these ships in 2016. Overall, the figure of Finns gambling on foreign operators’ sites or those maintained by the Åland Islands2 gambling operator PAF varied between 3% and 6%. In general, and with the exception of scratch cards, men gambled on all game types more than did women.

In the clinical sample, the most popular game types were EGMs in places other than casino venues (84%), weekly lottery games (80%), scratch cards (68%), and low-paced lottery games (66%). Almost half of the respondents (45%) had gambled daily fast-paced lottery games. Among this sample, over one-fifth (22%) had gambled at Casino Helsinki, and one-third (34%) had gambled on casino games outside the casino. Male respondents reported more often than women that they had gambled on betting games and casino games operated outside the casino. Men also reported having participated in private betting games more often than women, while women played scratch cards more often than did men.

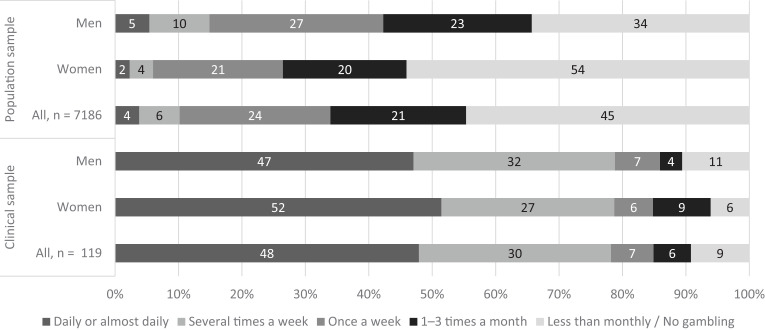

The most common frequency of gambling in the population sample was once a week: 34% of the respondents had gambled on a weekly basis (Figure 1), men gambling more often than women. Most typically, men gambled once a week (27%), while women gambled typically less than monthly (33%). The proportion of weekly gamblers was higher among the older age groups, and was the highest among those aged 50−64 (44%) and 65−74 (45%).

Figure 1.

Past-year gambling frequency in 2016 by gender (%).

The majority (85%) of the respondents in the clinical sample had gambled on a weekly basis in 2016. The most typical gambling frequency in this clinical population was daily or almost daily gambling (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in gambling frequency between the genders or different age groups among the clinical sample.

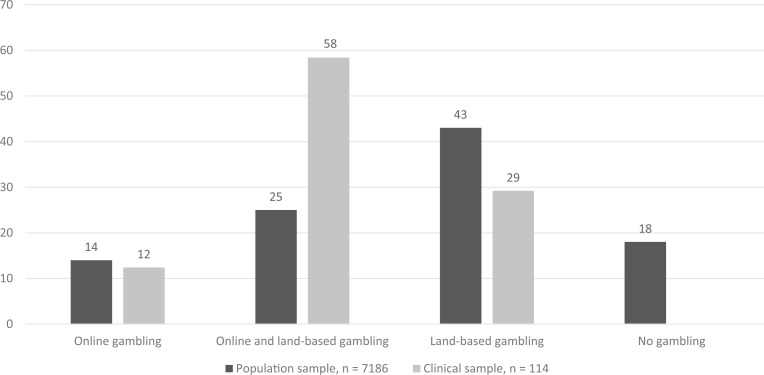

Online gambling was relatively common among the population sample (Figure 2); 14% had gambled online only. Every fourth respondent had gambled both online and land-based, with men gambling online more frequently than women. The proportion of respondents who reported that they had gambled only online was the largest in the 50–64 years age group. Of those who gambled both online and land-based, the greatest proportion was found in the 25–34 years age group, whereas the proportion of land-based gamblers was highest among those aged 65 years or older.

Figure 2.

Gambling mode in 2016 (%).

The proportion of online gamblers in the clinical sample was 70% (Figure 2), but only 12% had gambled online only. Among this sample, multi-mode gambling, including both online and land-based gambling, was relatively common (58%). The proportion of those who only gambled online was higher among women (25%) than men (8%), yet men gambled more (65%) than women (41%) both online and land-based. The proportion of gamblers who only gambled online was highest in the 35–44 years age group.

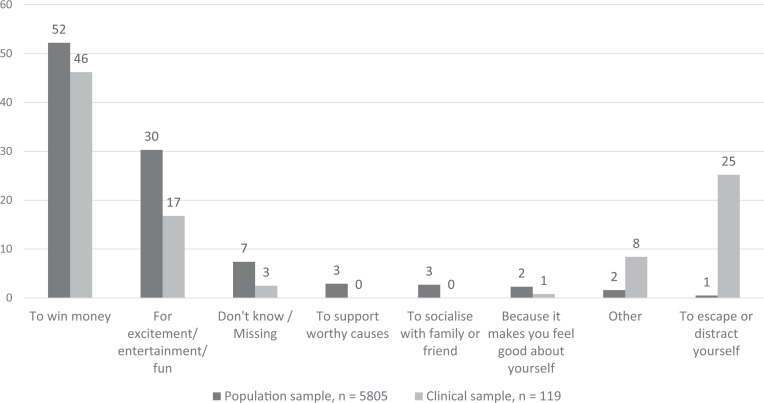

Analysis of the reasons for gambling in the population sample shows that more than half (52%) of those who had gambled in 2016 reported gambling to win money, and almost a third (30%) gambled for excitement, entertainment, and fun (Figure 3). Men tended to gamble more often for excitement, entertainment, and fun, while women’s gambling was more often motivated by a wish to win money. Only in the youngest age group was the most common reason for gambling excitement, entertainment, and fun.

Figure 3.

Primary motivation for gambling in 2016 among past-year gamblers (%).

In the clinical sample, nearly half (46%) had gambled to win money; one-quarter (25%) gambled to escape or take their mind away from other issues; and less than one-fifth (17%) gambled for excitement, entertainment, or fun (Figure 3). Escape as a motive was more common for women, but there were no significant differences between the different age groups.

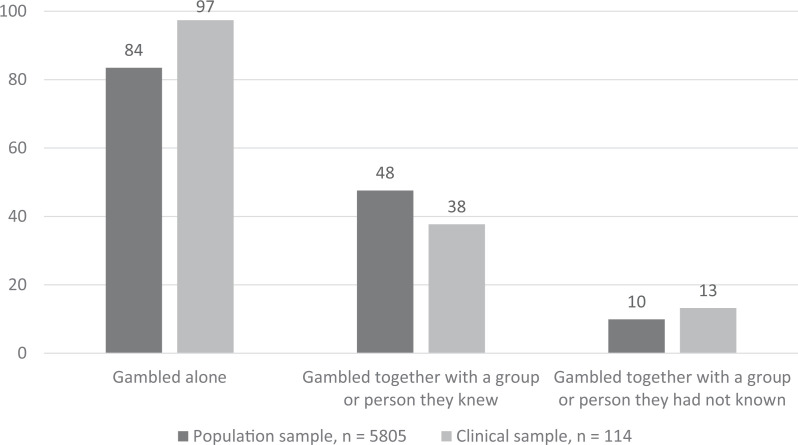

Gambling habits

The respondents gambled mainly alone (84% in the population sample and 97% in the clinical sample), with people they knew (48% vs. 38%, respectively), and with strangers (10% vs. 13%, respectively) (Figure 4). Men gambled alone more often than women. Only in the youngest age group was it more common to gamble with familiar people than alone. There were no significant differences in gambling habits between the genders or different age groups.

Figure 4.

Social context of gambling in 2016 (%).

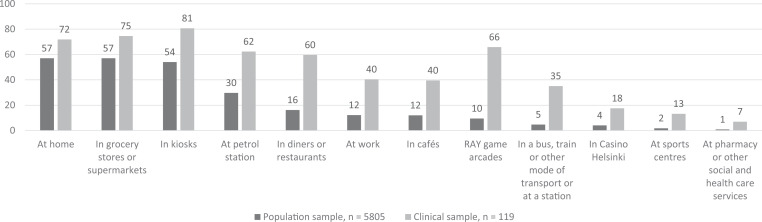

The significance of the social context of gambling activity followed rather similar patterns in both samples, but there were greater differences in the gambling environments (Figure 5). In the population sample, the most common place to gamble was at home (57%), in grocery stores or supermarkets (57%), and kiosks (54%), as well as petrol stations (30%) and restaurants or diners (16%). In the population sample, men gambled more in all environments; the gender differences were most visible in gambling at petrol stations, cafés, and restaurants or diners.

Figure 5.

Gambling environments in 2016 (%).

Respondents in the clinical sample reported that their most common gambling environments were kiosks (81%), grocery stores or supermarkets (75%), and home (72%). Finland’s Slot Machine Association (RAY) gaming arcades were also popular gambling environments (66%). Greater variation in gambling environments also meant that the clinical population tended to gamble on a greater variety of games.

Gambling-related harm for the gamblers

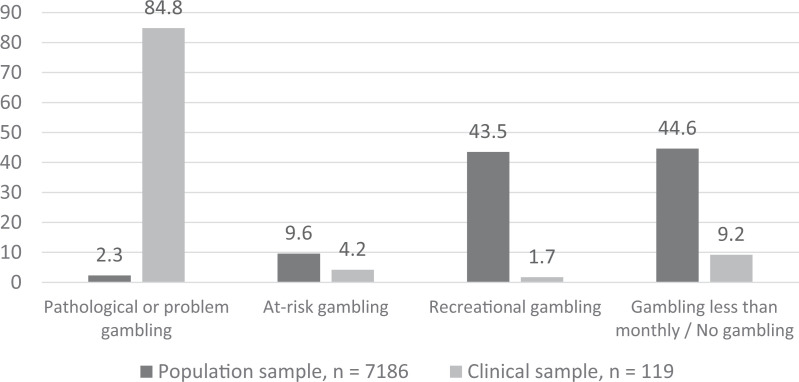

In the population sample, 2.3% of respondents met the definition of pathological or problem gamblers (Figure 6). This corresponds to 38,404 residents in Uusimaa, Pirkanmaa, and Kymenlaakso. In addition, 10% of the population sample fulfilled the criteria of at-risk gamblers. Among the clinical sample, as many as 85% of the respondents met the criteria of pathological or problem gamblers, and 4% were at-risk gamblers.

Figure 6.

Past-year gambling severity in 2016 (Problem and Pathological Gambling Measure).

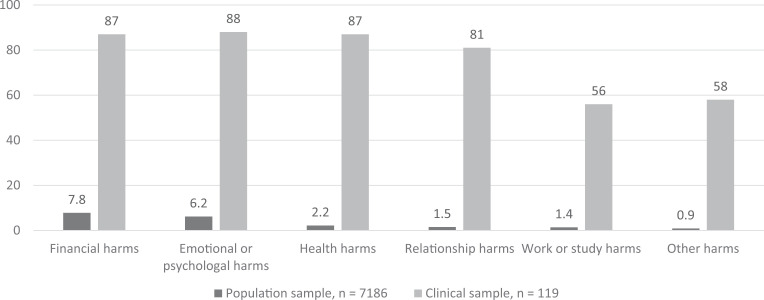

Of the respondents in the population sample, 11% had experienced at least one gambling-related harm during 2016. Converted into a numerical share of the population base, this figure corresponds to a total of 190,928 residents living in Uusimaa, Pirkanmaa, or Kymenlaakso. Men had, throughout, experienced more gambling-related harm than women. The most typical harms were financial (8%) or emotional/psychological (6%) harms (Figure 7). In general, gambling-related financial harm, harm related to work and studies, health problems, emotional harms, and other harms tended to decline the older the age group. However, the reported amount of relationship problems did not differ between the age groups.

Figure 7.

Proportion of gambling-related harm in 2016 (%).

The respondents in the clinical sample had experienced a notable amount of harm from their gambling. They reported gambling-related emotional/psychological harms (88%), financial harms (87%), health harms (87%), and relationship harms (81%) in 2016. Men experienced more work- and study-related harm than women. Gambling-related financial harm was most common among the youngest age groups.

On the whole and in both samples, the most typical gambling-related financial harms were reduced spending money and less money available for such recreations as eating out, going to movies, or other entertainment (Table 1). In the population sample, the third most common financial harm was reduced savings (2%), while the third most common harm in the clinical sample was late payment of bills (66%). Furthermore, almost half (45%) of the respondents in the clinical sample had run into debt problems or were in a vicious circle of debt (payment default, recovery, distraint, etc.), and one-third (32%) had turned to income support or services and assistance provided by the church, parishes, or other types of non-governmental organisations (food banks, breadlines).

Table 1.

Gambling-related harm among both population and clinical sample in Finland during 2016.

| Population sample | Clinical sample | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Financial harm | ||||

| Reduction of available spending money | 363 | 5.7 | 90 | 75.6 |

| Reducing of my savings | 112 | 1.7 | 58 | 48.7 |

| Less spending on recreational expenses such as eating out, going to movies, or other entertainment | 169 | 2.7 | 81 | 68.1 |

| Increased credit card debt | 25 | 0.4 | 57 | 47.9 |

| Sold personal items | 19 | 0.3 | 40 | 33.6 |

| Less spending on essential expenses such medication, healthcare, and food | 62 | 1.1 | 68 | 57.1 |

| Less spending on beneficial expenses such as insurances, education, car, and home maintenance | 54 | 0.9 | 61 | 51.3 |

| Late payment on bills (e.g., utilities, rates) | 47 | 0.8 | 79 | 66.4 |

| Took on additional employment | 32 | 0.5 | 24 | 20.2 |

| Needed assistance from welfare organisations (food banks or emergency bill payments) | 26 | 0.4 | 38 | 31.9 |

| Needed emergency or temporary accommodation | 6 | 0.1 | 4 | 3.4 |

| Loss of significant assets (e.g., car, home, business, superannuation) | 6 | 0.1 | 11 | 9.2 |

| Loss of supply of utilities (electricity, gas, etc.) | 8 | 0.1 | 7 | 5.9 |

| Bankruptcy | 19 | 0.3 | 53 | 44.5 |

| Emotional/psychological harm | ||||

| Feelings of extreme distress | 84 | 1.4 | 97 | 81.5 |

| Felt ashamed of my gambling | 82 | 1.3 | 85 | 71.4 |

| Had regrets that made me sorry about my gambling | 290 | 4.6 | 93 | 78.2 |

| Felt like a failure | 121 | 2.0 | 89 | 74.8 |

| Felt insecure or vulnerable | 30 | 0.5 | 65 | 54.6 |

| Felt worthless | 27 | 0.5 | 66 | 55.5 |

| Feelings of hopelessness about gambling | 56 | 0.9 | 85 | 71.4 |

| Felt angry about not controlling my gambling | 81 | 1.3 | 93 | 78.2 |

| Felt distressed about my gambling | 37 | 0.6 | 71 | 59.7 |

| Thought of running away or escape | 31 | 0.5 | 64 | 53.7 |

| Health harm | ||||

| Reduced physical activity due to my gambling | 36 | 0.6 | 56 | 47.1 |

| Didn’t eat as much or as often as I should | 28 | 0.5 | 53 | 44.5 |

| Ate too much | 28 | 0.4 | 23 | 19.3 |

| Loss of sleep due to spending time gambling | 47 | 0.8 | 72 | 60.5 |

| Neglected my hygiene and self-care | 15 | 0.3 | 26 | 21.8 |

| Neglected my medical needs (including taking prescribed medications) | 11 | 0.2 | 16 | 13.4 |

| Increased my use of tobacco | 41 | 0.7 | 50 | 42.0 |

| Increased my consumption of alcohol | 36 | 0.6 | 29 | 24.4 |

| Loss of sleep due to stress or worry about gambling or gambling-related problems | 41 | 0.7 | 67 | 56.3 |

| Increased experience of depression | 46 | 0.7 | 70 | 58.8 |

| Unhygienic living conditions (living rough, neglected or unclean housing, etc.) | 10 | 0.2 | 21 | 17.6 |

| Increased use of health services due to health issues caused or exacerbated by my gambling | 9 | 0.2 | 15 | 12.6 |

| Required emergency medical treatment for health issues caused or exacerbated by gambling | 2 | 0.0 | 8 | 6.7 |

| Committed acts of self-harm | 7 | 0.1 | 7 | 5.9 |

| Attempted suicide | 5 | 0.1 | 6 | 5.0 |

| Stress-related health problems (e.g., high blood pressure, headaches) | 19 | 0.3 | 37 | 31.1 |

| Work/study harm | ||||

| Reduced performance at work or study (due to tiredness or distraction) | 31 | 0.5 | 51 | 42.9 |

| Was late from work or study | 11 | 0.2 | 27 | 22.7 |

| Used my work or study time to gamble | 59 | 0.9 | 40 | 33.6 |

| Used my work or study resources to gamble | 12 | 0.2 | 9 | 7.6 |

| Was absent from work or study | 10 | 0.2 | 24 | 20.2 |

| Conflict with my colleagues | 5 | 0.1 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Lack of progression in my job or study | 15 | 0.3 | 24 | 20.2 |

| Excluded from study | 3 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Hindered my job-seeking efforts | 8 | 0.1 | 10 | 8.4 |

| Lost my job | 3 | 0.0 | 5 | 4.2 |

| Relationship harm | ||||

| Spent less time with people I care about | 49 | 0.8 | 61 | 51.3 |

| Neglected my relationship responsibilities | 33 | 0.6 | 54 | 45.4 |

| Felt belittled in my relationships | 21 | 0.3 | 32 | 26.9 |

| Spent less time attending social events (non-gambling related) | 31 | 0.5 | 53 | 44.5 |

| Experienced greater tension in my relationships (suspicion, lying, resentment, etc.) | 23 | 0.4 | 54 | 45.4 |

| Got less enjoyment from time spent with people I care about | 25 | 0.4 | 42 | 35.3 |

| Experiencing greater conflict in my relationships (arguing, fighting, ultimatums) | 15 | 0.2 | 49 | 41.2 |

| Social isolation (felt excluded or shut-off from others) | 24 | 0.4 | 57 | 47.9 |

| Threat of separation or ending a relationship/s | 11 | 0.2 | 31 | 26.1 |

| Actual separation or ending a relationship/s | 5 | 0.1 | 12 | 10.1 |

| Other harm | ||||

| Left children unsupervised | 3 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Arrested for unsafe driving | 5 | 0.1 | 2 | 1.7 |

| Felt that I had shamed my family name within my religious or cultural community | 6 | 0.1 | 14 | 11.8 |

| Had experiences with violence (including family/domestic violence) | 2 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Petty theft or dishonesty in respect of government, businesses, or other people (not family/friends) | 8 | 0.1 | 9 | 7.6 |

| Didn’t fully attend to needs of children | 6 | 0.1 | 11 | 9.2 |

| Felt less connected from religious or cultural community | 17 | 0.3 | 17 | 14.3 |

| Outcast from religious or cultural community due to involvement in gambling | 17 | 0.3 | 24 | 20.2 |

| Reduced my contribution to religious or cultural practices | 19 | 0.3 | 17 | 14.3 |

| Felt compelled or forced to commit a crime or steal to fund gambling or pay debts | 10 | 0.2 | 11 | 9.2 |

| Promised to pay back money without genuinely intending to do so | 15 | 0.3 | 44 | 37.0 |

| Took money or items from friends or family without asking first | 10 | 0.2 | 25 | 21.0 |

Harms Checklist (e.g., Browne et al., 2016; Langham et al., 2016; Li, Browne, Rawat, Langham, & Rockloff, 2016).

In the population sample, the most common emotional/psychological harm was having regrets that made the gamblers feel sorry about their gambling (5%) and experience feelings of failure (2%) or extreme distress (1%). In the clinical sample, the most commonly experienced emotional/psychological harms were feelings of extreme distress (82%), having regrets that made the gamblers feel sorry about their gambling (78%), and feeling angry about not controlling their gambling (78%) (Table 1).

The most common health-related harm was loss of sleep due to spending time on gambling (1% in the population sample and 61% in the clinical sample). Moreover, respondents in the population sample reported increased use of tobacco products (1%) and increased experience of depression (1%). Increased depression (Table 1) was experienced by 59% of the respondents among the clinical sample.

In the population sample, the most common relationship harm included spending less time with people one cared about (1%), neglecting one’s relationship responsibilities (1%), and spending less time attending social events (1%). In turn, in the clinical sample, the most common relationship harms were social isolation (48%) and experiencing greater tension in relationships (suspicion, lying, resentment, etc.) (41%) (Table 1).

In both samples, the most common work- or study-related harms were reduced performance (due to tiredness or distraction) and using one’s working or study time to gamble (Table 1). Overall, other harms were rather rare in the population sample. Conversely, in the clinical sample the most commonly experienced harms included promising to pay back money without genuinely intending to do so (37%), taking money or items from friends or family without asking first (21%), and feelings of being an outcast from a religious or cultural community due to involvement in gambling (20%).

Gambling-related harm for concerned significant others (CSOs)

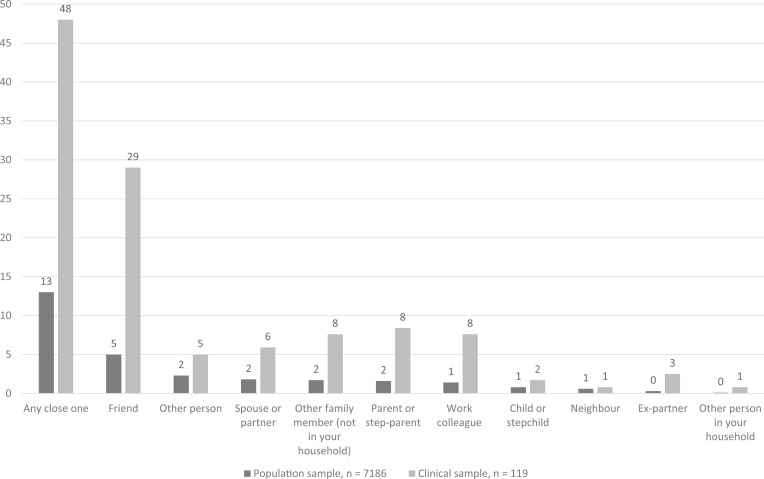

In the population sample, 13% of the respondents (14% of women and 12% of men) were identified as concerned significant others, corresponding to a total of 223,178 residents in Uusimaa, Pirkanmaa, and Kymenlaakso. The person gambling was typically a friend (5%) (Figure 8). The proportion of CSOs was highest among the 18–24 years (22%) and 25−34 years (16%) age groups.

Figure 8.

Proportion of concerned significant others of problem gamblers in 2016 (%).

Moreover, gambling-related harm caused by someone else was experienced by 6% of the respondents (7% of women and 4% of men) in the population sample. These harms included concerns about the health or wellbeing of someone close to them (2%) and emotional distress, such as stress, anxiety, guilt, and depression (2%). Harms for CSOs also included relationship problems, such as arguments, distrust, divorce, or separation (1%) and other interpersonal relationship problems, such as quarrels, isolation, and distancing oneself from friends (1%). Women experienced more of these harms than men.

In the clinical sample, as many as 48% of the respondents identified as CSOs (27% of women, 57% of men). The person whose gambling affected them was also here most often a friend (29%) (Figure 8). Over one-quarter or 28% of the respondents (15% of women, 33% of men) reported at least one gambling-related harm caused by a person in their closest circle. The most common gambling-related harms for the CSOs were emotional distress (20%); health harm, such as sleep problems, headaches, backache, or stomach aches (14%); and financial harm, such as payment issues, loans related to gambling, or loss of credibility (13%).

Opinions on gambling advertising

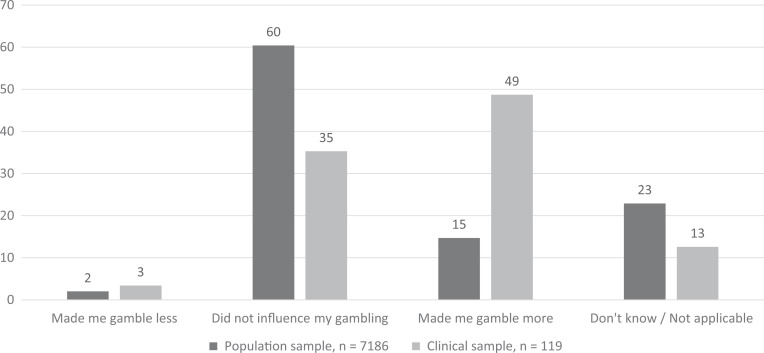

The majority of the population-based respondents (59%) were satisfied with the gambling-related advertising by the Finnish operators in 2016. One-fifth felt that they had been exposed to too much advertising (Figure 9), which was more often reported among men than women and more regularly reported among young adults in the 18–24 years (23%) and 25–34 years (21%) age groups. In the clinical sample over two-thirds (68%) of the respondents thought there had been too much advertising. No one felt that there had not been enough advertising. There were no significant differences regarding views on gambling advertising between the genders or age groups.

Figure 9.

Overall views on extent of gambling advertising of the Finnish monopoly companies in 2016 (%).

In the population sample, 15% of the respondents felt that the Finnish gambling operators’ advertising had made them gamble more, while the majority (60%) said that it had not had any effect on their gambling behaviour (Figure 10). The proportion of men (66%) who felt it had no effect was larger than that of women (56%). The proportion of respondents who felt advertising had an effect (i.e., made them gamble more) was highest among the 24–34-year-olds (20%) and the 35–44-year-olds (19%). Also, respondents in these age groups felt they had been excessively exposed to gambling advertising.

Figure 10.

Respondents’ opinions about the impact of gambling advertising by the Finnish monopoly companies in 2016 (%).

In contrast to the 15% of the general population, about half (49%) of the respondents in the clinical sample reported that the Finnish gambling operators’ advertising had made them gamble more. Over one-third (35%) said that it had had no effect on their gambling. There were no significant differences in the impact of gambling advertising between the genders or different age groups.

Discussion

This research review paints a cross-sectional picture of gambling in Finland, where gambling was an extremely common activity in 2016: 83% of the population sample reported gambling, and one-third reported doing so on a weekly basis. In a Nordic comparison, Finns are the most active gamblers, and at-risk and problem gambling prevalence is also highest in Finland (Pallesen, 2017). Monitoring this widespread habit is especially relevant, as it is well established that the level of gambling participation and high levels of involvement are associated with gambling-related harm (Gainsbury, Russell, Hing, Wood, & Blaszczynski, 2013; McCready et al., 2008; Wardle et al., 2011). Problem gamblers often play large repertoires of games, with great intensity, and using different modes (Williams, Volberg, Stevens, Williams, & Arthur, 2017; Williams, West, & Simpson, 2012). It is therefore important to continue following up gambling participation and harms in the changing Finnish gambling scene.

Finnish men tend to gamble more often, on multiple game types, and spend more money on gambling than women (Salonen & Raisamo, 2015; Turja et al., 2012). Based on this study, and previous Finnish surveys too, men also gamble more on all game types except scratch cards (e.g., Salonen & Raisamo, 2015; Turja et al., 2012). Women have been shown to prefer games of chance (slot machine gambling, scratch cards, bingo), while men prefer games with a perceived skill component or games which provide excitement (table games and betting). Although this report has neither focused explicitly nor in-depth on gender differences, there are some gender-specific results that may shed light on the population trends. Gambling frequency differed between men and women only in the population sample, which implies that gender differences are less articulated when gamblers lose control.

In the clinical sample, the most frequently played games were EGMs. This is interesting given the ongoing discussions about the availability of EGMs, which are considered more accessible in Finland than internationally. A risk that has been identified as escalating the likelihood of developing gambling-related harm is increased availability and accessibility of various types of games in both online and real-world environments (Gainsbury, Liu, Russell, & Teichert, 2016). It is therefore vital to keep mapping the regional differences in the location of EGMs and to seek sustainable ways to prevent excessive gambling, for example by reducing availability of gambling in certain social settings such as areas of low socioeconomic status (Selin et al., 2016). While roughly one-tenth of the respondents reported gaming only online, the risk seemed to increase a great deal when gambling was performed in many different modes (Salonen, Castrén et al., 2017; Salonen, Latvala et al., 2017).

Winning money was the most common motivational factor, but the second most common factor was excitement, entertainment, and fun in the general population, and escape in the clinical population. In the clinical sample, women gambled more often than men to escape. Overall, every third gambler gambled for excitement, entertainment, and fun, while the corresponding figure among the clinical sample was 17%. Furthermore, 84% of the population sample and 97% of the clinical sample had gambled alone. Men would typically gamble for excitement, to pass time, and for fun, while women would concentrate more on the possibility of winning money.

In the clinical sample, too, the most common reason for gambling was the chance of winning money. Previous Finnish research has shown that while people with high incomes would spend larger sums on gambling, it was people with lower incomes who would use larger amounts for gambling when the sums were viewed as relative amounts of incomes (Castrén, Kontto, Alho, & Salonen, 2017; Salonen, Kontto, Alho, & Castrén, 2017). Gambling can be an effort to solve economic problems, and for problem gamblers a new chance of winning back money may seem like the only way out of considerable debts (Heiskanen, 2017). Mapping the reasoning behind different types of gambling provides valuable knowledge for the planning of help provision.

Most typically the respondents gambled alone, and the most common gambling environments were kiosks, grocery stores or supermarkets, and home. Game venues and the casino were more common gambling sites for the clinical sample who had sought help for their problems. Only in the youngest age group was gambling with familiar people more common than gambling alone, which reflects the social context of gambling young adults (Hing, Russell, Tolchard, & Nower, 2016). Overall, the older the gamblers were, the more rarely they would gamble with people they knew. The youngest age group also differed from other age groups in terms of their game type preferences: gambling in RAY games arcades and Casino Helsinki was most common among 18–24-year-olds. The social context was important for the younger responders’ gambling, and the social aspects of gambling have also been shown to entail certain protective functions – such as peers exercising social control – in view of gambling-related problems (LaPlante, Nelson, LaBrie, & Shaffer, 2009).

In 2016, the most typical gambling-related harms were financial or emotional/psychological harms in the Finnish population sample. Monetary trouble is a highly prevalent harm in studies on gambling-related harm, and these issues tend to be entangled with other areas of problems, for example reducing quality of life (Langham et al., 2016; Shannon et al., 2017). Overall, women experienced a greater number of harms than men in the population sample.

Respondents in the clinical sample had experienced, as expected, a considerable amount of harm. The most commonly experienced harms were financial harms and emotional/psychological harms, but also harms related to health and relationships. The more severe the harm was, the more uncommon its occurrence. Yet, severe problems have often significant long-standing consequences. For example, almost half of the clinical survey respondents had experienced indebtedness or were in a debt spiral.

In the clinical sample, men would more often experience gambling-related work and study harm compared with women, but there were no significant gender differences in the other harm categories. Considering the level of gambling and gambling-related harm in Finland, it would make sense to add questions about gambling habits as a part of routine screening along with the use of other addictive substances (tobacco and alcohol) in public health and occupational settings. Problem gambling should also be included in substance-abuse policies in work places.

Of the population sample, 13% of the respondents were identified as concerned significant others of problem gamblers, while the corresponding figure was 48% among the clinical sample. In the general population, the CSO was more commonly a woman, in the clinical sample more often a man. To our knowledge, this study is the first population-based survey examining the perspective of the CSO in a past-year time frame (see Salonen et al., 2016; Salonen, Castrén, Alho, & Lahti, 2014; Svensson, Romild, & Shepherdson, 2013; Wentzel, Øren, & Bakken, 2008). Finnish studies suggest that the proportion of CSOs has been 19% in a life timeframe (Salonen, Alho, & Castrén, 2015; Salonen et al., 2016; Salonen et al., 2014). Each gambler has been generally estimated to have 10–15 CSOs (Lesieur, 1998).

In both samples, the person whose gambling was causing harm was most commonly a friend, which is in line with previous population studies (Salonen et al., 2015; Salonen et al., 2014; Salonen & Raisamo, 2015). In the clinical sample the number of friends was rather large, which may be because the help-seeking gamblers attend peer-support groups.

In the population sample, 6% of all respondents had experienced harm from the gambling of someone close to them in 2016. Most commonly this led to concerns about the gamblers’ wellbeing, health, and levels of emotional stress. Female CSOs often experience more harm than men (Salonen et al., 2016). The harms experienced by CSOs are partly the same as those experienced by gamblers themselves (cf. Li et al., 2016; Salonen et al., 2016). In the clinical sample the CSOs reported experiencing emotional stress, health-related, and financial harm.

As to gambling advertising, the respondents in the clinical sample felt that they had been exposed to this too often and that this had increased their gambling in 2016. Gambling advertising possibly triggers impulses to gamble and may also raise already high levels of gambling, causing severe problems for problem gamblers in particular in terms of whether they can gamble in a controlled manner or not at all (Binde, 2009; Hing, Cherney, Blaszczynski, Gainsbury, & Lubman, 2014). Gambling marketing has been shown to normalise gambling and to serve as an incitement for gamblers to continue gambling, but it also heightens the risks of relapse for people trying to quit their gambling habit (Binde, 2014). In light of the study’s results, we need to discuss principles for good marketing practice to a larger extent (cf. Castrén, Murto, Alho, & Salonen, 2014; Monaghan, Derevensky, & Sklar, 2008) and follow up the views on gambling marketing and advertising in the second wave of the study.

In the population survey, the response rate was 36%, which is better than the international average for online and postal surveys (Williams, Volberg, & Stevens, 2012). Overall, female and older respondents were more eager to participate in both surveys compared with men and younger respondents. In the population survey, around 70% participated in the online survey and the rest in the postal survey. In the online survey, the proportion of past-year gamblers, online gamblers, and problem gamblers was higher than among the respondents of the postal survey (Salonen, Latvala et al., 2017). Gambling harm was measured by the Harms Checklist (Browne et al., 2016; Langham et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016), which gauges comprehensively the negative consequences from gambling. It is, however, important to acknowledge that harm can vary from mild to severe and from short term to long term. Milder types of harm were more common throughout. The strength of these two studies lies also in the use of the Problem and Pathological Gambling Measure (PPGM: Williams & Volberg, 2010), currently the most comprehensive tool for assessing different types of gambling harm and shown to be the most sensitive and the most accurate measure in identifying problem gambling (Williams & Volberg, 2014). These two instruments were translated into Finnish and back-translated into English in collaboration with the instrument developers.

Conclusions and way ahead

The broad aggregated view yields insights into population-based and clinical perspectives for gambling and gambling-related harm. The Finns who participated in the 2016 surveys gambled to a great extent. In the population survey, young adults and men differed based on their gambling habits and environments. Men gambled more often than women for excitement, entertainment and for fun, while women gambled more often than men to win money. Financial or emotional harms were most prevalent. Furthermore, in the population survey the CSOs were more often women, and women experienced more gambling-related harm caused by someone else. In the clinical survey, respondents were heavy consumers without clear gender differences. Every fourth help-seeking respondent gambled to escape, and escape as a motive was more common for women.

Help-seeking gamblers experienced a noteworthy amount of harm and almost half of the respondents were identified as CSOs. In the clinical sample, CSOs were more often men, and men experienced more gambling-related harm caused by someone else. In addition, those who sought help for excessive or problematic gambling were more likely to think that their gambling was influenced by gambling advertising.

The results of the clinical sample throughout imply that when gambling gets out of control, the distinctions between gamblers’ habits diminish, become more streamlined, and focus on gambling per se – doing it often, and in greater varieties (different game types). There is a heightened need to monitor gambling and gambling-related harm on the population level, especially amongst heavy consumers, in order to understand which external factors of policy and governance may contribute to the shift from recreational to problem gambling. In the future, these two data sets will be used as a first wave of measurement for a follow-up study on the Finnish monopoly merger of 2017. As the levels of gambling and experienced harm are divided differently age-wise for male and females, the study recognises a need to explore more closely the logics and trajectories of male and female gambling in the Finnish population.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Jani Selin, Hannu Alho, and Maria Heiskanen for their input on the original reports. We also wish to express our gratitude to Johanna Järvinen-Tassopoulos, Miika Vuori, Matthew Browne, Rachel Volberg, and Robert Williams for their valuable help in translating and back-translating the measuring instruments. Furthermore, we wish to thank the staff at Statistics Finland and at the Peliklinikka Gambling Clinic for their contribution in the data collection, and Pirkko Hautamäki for revising the language of this review.

Notes

The Finnish gambling provision system was transformed in 2017, when three gambling monopoly operators were merged into a single gambling monopoly. Together with data from the second measurement point in 2018, the 2016 survey will give insights into if and how this gambling system change has affected the population’s gambling behaviour and gambling-related harm.

Åland is an autonomous, demilitarised and mainly Swedish-speaking region of Finland.

Ethics: The Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Health and Welfare approved the research protocol. Permission to collect the clinical data at the Gambling Clinic was obtained from the City of Helsinki, the City of Vantaa, the management group of Peluuri and the Finnish Blue Ribbon. Potential participants received written information about the study and the principles of voluntary participation.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The study was funded from the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health within the objectives of the §52 Appropriation of the Lotteries Act. The money originally stems from the gambling monopoly. The two research groups that the authors are part of at the National Institute for Health and Welfare, and at the University of Helsinki both acquire funding for research through this system. The research conducted by these institutions is disentangled from the funding’s origin: the Ministry has had no role in the study design, analysis, or interpretation of the results of the manuscript or any phase of the publication process.

Contributor Information

Anne H. Salonen, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland

Matilda Hellman, University of Helsinki, Finland.

Tiina Latvala, Finnish Foundation for Alcohol Studies, Finland.

Sari Castrén, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland; and University of Helsinki, Finland.

References

- Abbott M., Binde P., Clark L., Hodgins D., Korn D., Pereira A.…Williams R. (2015). Conceptual framework of harmful gambling: An international collaboration revised edition. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO; ). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Binde P. (2009). Exploring the impact of gambling advertising: An interview study of problem gamblers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 7(4), 541–554. [Google Scholar]

- Binde P. (2014). Gambling advertising: A critical research review. London, UK: The Responsible Gambling Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M., Bellringer M., Greer N., Kolandai-Matchett K., Rawat V., Langham E.…Abbott M. (2017). Measuring the burden of gambling harm in New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M., Greer N., Rawat V., Rockloff M. A. (2017). Population-level metric for gambling related harm. International Gambling Studies, 17(2), 163–175. doi:10.1080/14459795.2017.1304973 [Google Scholar]

- Browne M., Langham E., Rawat V., Greer N., Li E., Rose J.…Best R. (2016). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation; Retrieved from https://www.responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/28465/Browne_assessing_gambling-related_harm_in_Vic_Apr_2016-REPLACEMENT2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Browne M., Rawat V., Greer N., Langham E., Rockloff M., Hanley C. (2017). What is the harm? Applying a public health methodology to measure the impact of gambling problems and harm on quality of life. Journal of Gambling Issues, 37, 28–50. doi:10.4309/jgi.2017.36.2 [Google Scholar]

- Castrén S., Kontto J., Alho H., Salonen A. H. (2017). The relationship between gambling expenditure, sociodemographics, health-related correlates and gambling behaviour: A cross-sectional population-based survey in Finland. Addiction, 113(1), 91–106. doi:10.1111/add.13929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castrén S., Murto A., Alho H., Salonen A. H. (2014). Rahapelimarkkinointi yhä aggressiivisempaa – unohtuivatko hyvät periaatteet? [Gambling advertising becoming more aggressive – did we forget the good principles?]. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka, 79(4), 438–443. [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S., Liu Y., Russell A., Teichert T. (2016). Is all Internet gambling equally problematic? Considering the relationship between mode of access and gambling problems. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 717–728. [Google Scholar]

- Gainsbury S. M., Russell A., Hing N., Wood R., Blaszczynski A. (2013). The impact of internet gambling on gambling problems: A comparison of moderate-risk and problem Internet and non-Internet gamblers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 1092–1101. doi:10.1037/a0031475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiskanen M. (2017). Financial recovery from problem gambling: Problem gamblers’ experiences of social assistance and other financial support. Journal of Gambling Issues, 35, 24–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Cherney L., Blaszczynski A., Gainsbury S. M., Lubman D. I. (2014). Do advertising and promotions for online gambling increase gambling consumption? An exploratory study. International Gambling Studies, 4(3), 394–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hing N., Russell A., Tolchard B., Nower L. (2016). Risk factors for gambling problems: An analysis by gender. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(2), 511–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langham E., Thorne H., Browne M., Donaldson P., Rose J., Rockloff M. (2016). Understanding gambling related harm: A proposed definition, conceptual framework, and taxonomy of harms. BMC Public Health, 16(80). doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2747-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaPlante D. A., Nelson S. E., LaBrie R. A., Shaffer H. J. (2009). The relationships between disordered gambling, type of gambling, and gambling involvement in the British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2007. European Journal of Public Health, 21(4), 532–537. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckp177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesieur H. (1998). Costs and treatment of pathological gambling. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 556, 153–171. [Google Scholar]

- Li E., Browne M., Rawat V., Langham E., Rockloff M. (2016). Breaking bad: Comparing gambling harms among gamblers and affected others. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 223–248. doi:10.1007/s10899-016-9632-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCready J., Mann R. E., Zhao J., Eves R. (2008). Correlates of gambling-related problems among older adults in Ontario. Journal of Gambling Issues, 22, 174–194. [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan S., Derevensky J., Sklar A. (2008). Impact of gambling advertisement and marketing on children and adolescents: Policy recommendations to minimize harm. Journal of Gambling Issues, 22, 252–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pallesen S. (2017, May). Prevalence of gambling problems in the Nordic countries. Paper presented at the meeting of the Stiftelsen Nordiska Sällskapet för Upplysning om Spelberoende, Odense, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A. H., Alho H., Castrén S. (2015). Gambling frequency, gambling problems and concerned significant others of problem gamblers in Finland: Cross-sectional population studies in 2007 and 2011. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 43, 229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A. H., Alho H., Castrén S. (2016). The extent and type of gambling harms for concerned significant others: A cross-sectional population study in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(8), 799–804. doi:10.1177/1403494816673529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A. H., Castrén S., Alho H., Lahti T. (2014). Concerned significant others of people with gambling problems in Finland: A cross-sectional population study. BMC Public Health, 14(398). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A., Castrén S., Latvala T., Heiskanen M., Alho H. (2017). Rahapelikysely 2016. Rahapelaaminen, rahapelihaitat ja rahapelien markkinointiin liittyvät mielipiteet rahapeliongelmaan apua hakevilla Peliklinikan asiakkailla [Gambling Harms Survey 2016. Gambling, gambling-related harm, and opinions on gambling marketing among gambling clinic clients]. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) Report 8/2017. Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A. H., Kontto J., Alho H., Castrén S. (2017). Suomalaisten rahapelikulutus – keneltä rahapeliyhtiöiden tuotot tulevat? [Gambling expenditure in Finland – who contributes the most to the profits of the gambling industry?]. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka, 82(5), 549–559. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A., Latvala T., Castrén S., Selin J., Hellman M. (2017). Rahapelikysely 2016. Rahapelaaminen, rahapelihaitat ja rahapelien markkinointiin liittyvät mielipiteet Uudellamaalla, Pirkanmaalla ja Kymenlaaksossa [Gambling Harms Survey 2016. Gambling, gambling-related harm, and opinions on gambling marketing in Uusimaa, Pirkanmaa, and Kymenlaakso]. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) Report 9/2017. Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Salonen A. H., Raisamo S. (2015). Suomalaisten rahapelaaminen 2015. Rahapelaaminen, rahapeliongelmat ja rahapelaamiseen liittyvät asenteet ja mielipiteet 15–74-vuotiailla [Finnish gambling 2015. Gambling, gambling problems, and attitudes and opinions on gambling among Finns aged 15–74]. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) Report 16/2015 Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Selin J., Raisamo S., Murto A. (2016). Alueelliset erot subjektiivisesti koetussa rahapeliongelmassa [Regional differences in subjective perception of problem gambling]. Yhteiskuntapolitiikka, 81(4), 429–436. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon K., Anjoul F., Blaszczynski A. (2017). Mapping the proportional distribution of gambling-related harms in a clinical and community sample. International Gambling Studies, 17(3), 366–385. doi:10.1080/14459795.2017.1333131 [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Romild U., Shepherdson E. (2013). The concerned significant others of people with gambling problems in a national representative sample in Sweden: A 1 year follow-up study. BMC Public Health, 13(1087). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turja T., Halme J., Mervola M., Järvinen-Tassopoulos J., Ronkainen J.-E. (2012). Suomalaisten rahapelaaminen 2011 [Finnish Gambling 2011]. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) Report 14/2012 Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle H., Moody A., Spence S., Orford J., Volberg R., Jotangla D.…Dobbie F. (2011). British Gambling Prevalence Survey 2010. London, UK: Gambling Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel H. G., Øren A., Bakken I. J. (2008). Gambling problems in the family: A stratified probability sample study of prevalence and reported consequences. BMC Public Health, 8(412). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. J., Pekow P. S., Volberg R. A., Stanek E. J., Zorn M., Houpt A. (2017). Impacts of gambling in Massachusetts: Results of a baseline online panel survey (BOPS). Amherst, MA: School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. J., Volberg R. A. (2010). Best practices in the population assessment of problem gambling. Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R., Volberg R. (2014). The classification accuracy of four problem gambling assessment instruments in population research. International Gambling Studies, 14(1), 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R., Volberg R., Stevens R. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends (Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care) Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. J., Volberg R. A., Stevens R. M. G., Williams L. A., Arthur J. N. (2017). The definition, dimensionalization, and assessment of gambling participation (Report prepared for the Canadian Consortium for Gambling Research). Alberta: Canadian Consortium for Gambling Research. [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. J., West B. L., Simpson R. I. (2012). Prevention of problem gambling: A comprehensive review of the evidence, and identified best practices (Report prepared for the Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre and the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care). Guelph, Ontario, Canada: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre. [Google Scholar]