Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: critical care, critical illness, intensive care units, outcome assessment, patient-reported outcome measures, quality of life

Objectives:

Although patient’s health status before ICU admission is the most important predictor for long-term outcomes, it is often not taken into account, potentially overestimating the attributable effects of critical illness. Studies that did assess the pre-ICU health status often included specific patient groups or assessed one specific health domain. Our aim was to explore patient’s physical, mental, and cognitive functioning, as well as their quality of life before ICU admission.

Design:

Baseline data were used from the longitudinal prospective MONITOR-IC cohort study.

Setting:

ICUs of four Dutch hospitals.

Patients:

Adult ICU survivors (n = 2,467) admitted between July 2016 and December 2018.

Interventions:

None.

Measurements and Main Results:

Patients, or their proxy, rated their level of frailty (Clinical Frailty Scale), fatigue (Checklist Individual Strength-8), anxiety and depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), cognitive functioning (Cognitive Failure Questionnaire-14), and quality of life (Short Form-36) before ICU admission. Unplanned patients rated their pre-ICU health status retrospectively after ICU admission. Before ICU admission, 13% of all patients was frail, 65% suffered from fatigue, 28% and 26% from symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively, and 6% from cognitive problems. Unplanned patients were significantly more frail and depressed. Patients with a poor pre-ICU health status were more often likely to be female, older, lower educated, divorced or widowed, living in a healthcare facility, and suffering from a chronic condition.

Conclusions:

In an era with increasing attention for health problems after ICU admission, the results of this study indicate that a part of the ICU survivors already experience serious impairments in their physical, mental, and cognitive functioning before ICU admission. Substantial differences were seen between patient subgroups. These findings underline the importance of accounting for pre-ICU health status when studying long-term outcomes.

With increasing survival rates of ICU patients (1, 2), leading to millions of ICU survivors worldwide every year (3), the focus of outcomes in critical care medicine is shifting from short-term mortality toward long-term consequences of critical illness (3, 4). Subsequently, it has become clear that many ICU survivors suffer, for months to even years, from physical, mental, and cognitive health problems (3, 5, 6), also known as “postintensive care syndrome” (PICS) (3). It impacts their daily functioning and quality of life (1, 3) and is associated with higher healthcare utilization due to readmissions, institutionalization, and required rehabilitation (7).

It is still largely unknown why some ICU patients successfully recover, whereas others do not (8). Although it is generally thought that long-term problems result from a complex relationship among patient characteristics, pre-ICU health status, critical illness, ICU treatments, and post-ICU factors (5, 9–11), recent studies have shown that the strongest predictors of long-term outcomes are not factors related to ICU admission or critical illness, but factors related to the health status before ICU admission (12–19). Pre-ICU psychologic morbidity is, for example, strongly associated with symptoms of depression after critical illness (20), and pre-ICU frailty with a lower quality of life and functional dependency after ICU discharge (21).

It is, therefore, remarkable that many studies on long-term outcomes of ICU patients do not take the preexisting health status into account (12, 22), potentially inducing bias by overestimating the attributable effects of critical illness (14, 23–25). Besides, a full understanding of the pre-ICU health status would help us to better characterize patients before their ICU admission (15) and to identify patients who are at greatest risk for specific impairments, and who may benefit from preventive interventions (3). Additionally, because the ideal outcome for our patients is to return to their preexisting state or a state expected for a person of the same age and medical condition (4), insight in the pre-ICU health status may guide the treatment decision-making (14, 18). Previous studies that did assess the pre-ICU health status focused often on one specific patient group, such as patients of 80 years old or older (26), or on one specific pre-ICU health domain, for example, cognitive functioning (13, 27), frailty (21), or quality of life (28, 29).

Because PICS comprises impairments in physical, mental, and cognitive health (3), the aims of this study were to get insight into the pre-ICU physical, mental, and cognitive health status and quality of life of ICU patients, and to assess differences between patient subgroups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

Data were obtained from a large ongoing longitudinal prospective multicenter cohort study (MONITOR-IC study) (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03246334). The MONITOR-IC study started in 2016, aiming to study 5-year physical, mental, and cognitive health outcomes of ICU survivors. Detailed information regarding this study is described in the study protocol (30). The study has been approved by the research ethics committee of the Radboud University Medical Center, CMO region Arnhem-Nijmegen (2016-2724). Each included participant or legal representative provided written informed consent.

Study Population

Patients were included when they were 16 years old or older and admitted for at least 12 hours to the ICU of one of the participating hospitals (one academic and three teaching hospitals) between July 2016 and December 2018. Patients with a life expectancy of less than 48 hours, receiving palliative care, or who could not read or speak the Dutch language were excluded.

Data Collection

Patients with a planned ICU admission received an information letter and informed consent form at the preoperative outpatient clinic. After informed consent, they were asked to complete the questionnaire a few days before their ICU admission. Patients with an unplanned ICU admission received the information letter and informed consent form while being in the ICU, or it was provided to their proxy. After informed consent, patients were asked to complete the questionnaire by rating their health retrospectively, recalling their health status before ICU admission.

Depending on patients’ or their proxies’ preferences, a self-administrated paper-based or online questionnaire was provided. Reminders were sent after 4 weeks, and 2 weeks later, a phone call was made. If patients did not respond in 90 days, they were excluded from the study.

Outcomes

The questionnaire consisted of the following validated instruments (more information about the instruments can be found in the study protocol) (30):

“Frailty” was measured using the Dutch version (31) of the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS) (32), consisting of one item comprising nine pictographs with a description of vulnerability and functional status. The score ranges from 1 “very fit” to 9 “terminally ill,” with higher scores indicating more frailty. Patients were classified as “non-frail” (CFS score, 1–4) or as “frail” (CFS score, 5–9).

“Fatigue” was measured using the eight-item subscale of the Checklist Individual Strength (CIS)-20 (33), consisting of a seven-point rating scale, with a total score ranging from 8 to 56. Higher scores indicate higher levels of fatigue. A score of greater than or equal to 27 indicated “mild fatigue,” and a score of greater than or equal to 37 indicated “severe fatigue.”

Symptoms of “anxiety” and “depression” were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (34), consisting of a seven-item anxiety subscale (HADS-Anxiety) and seven-item depression subscale (HADS-Depression). The four-point Likert scale ranged from 0 to 3, with total scores per subscale ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety or depression. Scores were categorized as “normal” (0–7), “mild” (8–10), “moderate” (11–14), and “severe” (15–21).

“Cognitive functioning” was assessed using the abbreviated 14-item Cognitive Failure Questionnaire (CFQ)-14 (35). The five-point Likert scale ranged from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“very often”). The scores were transformed to a 0–100 total score, with higher scores indicating more cognitive failure. A cut-off of greater than 43 was used to distinguish normal from abnormal score (36). This instrument has been added to the questionnaire in February 2017. Data regarding the cognitive health status of patients who were included between July 2016 and February 2017 are, therefore, missing.

“Quality of life” was assessed with the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) (37), consisting of eight domains, scoring form 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Scores were aggregated into two summary measures: Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Summary (MCS) scores.

Patient demographics, such as age, sex, education level, and marital status, were retrieved from the questionnaire. Other variables, such as admission type (classified as elective surgical, medical, or urgent surgical), Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV score, and ICU and hospital length of stay (LOS), were retrieved from the electronic health record.

Statistical Analysis

The focus of the MONITOR-IC study is the health outcomes of ICU survivors; therefore, only ICU survivors were included in the analysis. Continuous data were, depending on their distribution, presented as means with sd or medians with interquartile range, and categorical data with numbers and percentages. Because the majority of the included patients had a planned ICU admission, we analyzed patients with a planned and unplanned ICU admission separately.

Differences in characteristics and outcomes between planned and unplanned ICU patients were analyzed using the independent-samples t test, Mann-Whitney U test, or chi-square test. Differences between patients and proxies were analyzed in the same way. Missing values in the CIS-8, HADS, CFQ-14, and SF-36 were imputed using the half-rule (38), in which missing items were replaced with the mean of the answered items, if at least half of the items in the (sub)scale had been answered or half plus one in case of scales with an odd number of items.

To assess the generalizability of the findings, characteristics of study participants were compared with ICU survivors of all Dutch hospitals (n = 82) being admitted between July 2016 and December 2018 as well. Data from these patients were retrieved from the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation registry (39), a national quality registry for ICU care, in which patient demographic, clinical, and characteristics are registered.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Values of p less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

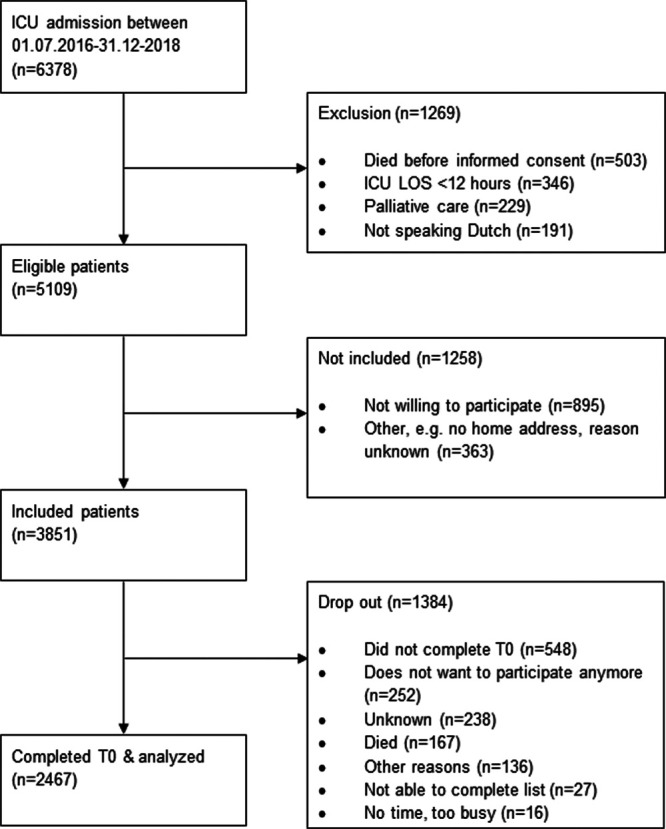

Of the 5,109 patients who were eligible for this study, 3,851 patients were included, of which 2,467 (64%) completed the questionnaire (Fig. 1). The main reasons for dropout were no return of the questionnaire or withdrawal.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of multicenter cohort study. LOS = length of stay.

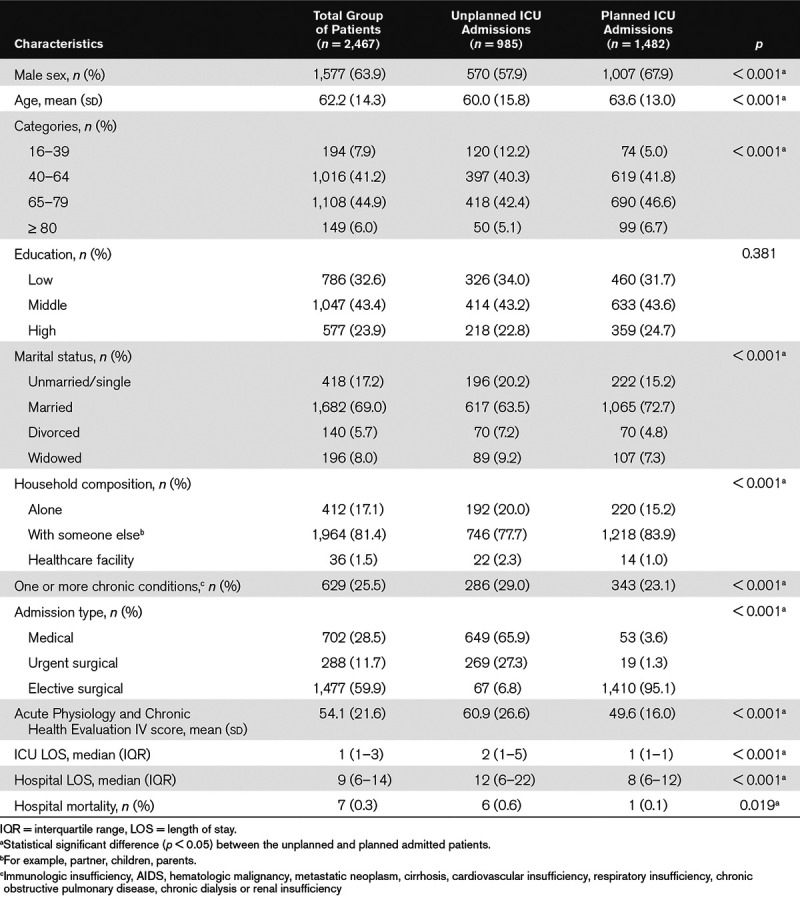

Patient Characteristics

The mean age of the 2,467 patients was 62.2 years (± 14.3), and 64% was male (Table 1). A quarter suffered from a chronic condition, with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (32%) being most prevalent. The median ICU and hospital LOS were 1 days (1–3 d) and 9 days (6–14 d), respectively.

TABLE 1.

Patient, Clinical, and ICU Characteristics: Differences Between Patients With an Unplanned and Planned ICU Admission

Compared with all ICU survivors (n = 183,362) in the Netherlands, our study participants were slightly younger, had less chronic conditions, and their hospital mortality rate was lower. However, the APACHE-IV scores, ICU LOS, and post-ICU LOS were higher (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F581).

Unplanned Versus Planned ICU Admission.

The majority of the patients (60%) had a planned ICU admission. Patients with an unplanned admission (n = 985) were significantly more often female (42% vs 32%), younger (mean age, 60 vs 64 yr), had higher mean APACHE-IV scores (60 vs 50), and had a longer median ICU (2 vs 1 d) and hospital (12 vs 8 d) LOS compared with patients with a planned admission (n = 1,482) (Table 1).

Patient Versus Proxy.

Nineteen percent of the questionnaires were completed by a proxy (n = 476). Patients who were not able to complete the questionnaire by themselves were more often female (43% vs 34%), living in a healthcare facility (4.5% vs 0.6%), having a medical (49% vs 24%) or urgent surgical (22% vs 9%) ICU admission, higher mean APACHE-IV scores (65 vs 51), and a longer median ICU (3 vs 1 d) and hospital (15 vs 8 d) LOS compared with patients who completed the questionnaire themselves (n = 1,906) (Supplemental Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F582).

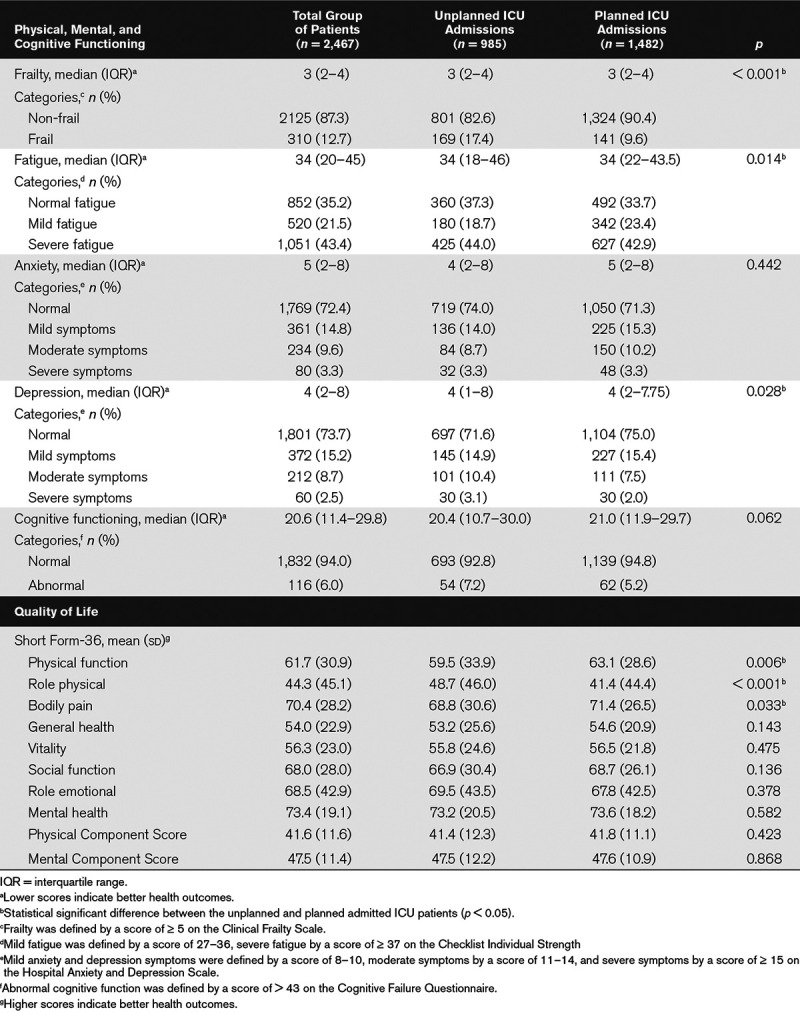

Pre-ICU Physical, Mental, and Cognitive Functioning and Quality of Life

Thirteen percent of the patients (n = 310) were frail before ICU admission (Table 2). Severe levels of fatigue were experienced by 43% of the patients (n = 1,051), mild levels by 22% (n = 520), and normal levels of fatigue by 35% (n = 852). Mild, moderate, and severe symptoms of anxiety were experienced by 15%, 10%, and 3% of the patients, and symptoms of depression by 15%, 9%, and 3% of the patients, respectively. Six percent (n = 116) of the patients rated their cognitive functioning as abnormal. The mean quality of life SF-36 PCS and MCS scores were 41.6 (± 11.6) and 47.5 (± 11.4), respectively. Compared with 1 year before ICU admission, 49% of the patients (n = 1,186) rated their health status as declined, 41% (n = 986) as the same, and 10% (n = 235) as improved.

TABLE 2.

Health Status and Quality of Life Before ICU Admission: Differences Between Patients With an Unplanned and Planned ICU Admission

Unplanned Versus Planned Admitted ICU Patients.

Unplanned and planned ICU patients differed in their pre-ICU health status (Table 2; and Supplemental Fig. 1, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F583). Patients with an unplanned ICU admission were more often frail (17% vs 10%) and experiencing symptoms of moderate (10% vs 7.5%) or severe depression (3% vs 2%) than patients with a planned ICU admission. Patients with a planned ICU admission were more often suffering from mild fatigue (23% vs 19%). No significant differences between the two groups were seen in anxiety and quality of life PCS and MCS scores.

Patient Versus Proxy.

Differences in pre-ICU health status were also seen in questionnaires completed by patients or proxies: in the proxy-completed questionnaires, patients experienced significantly more problems in frailty (23% vs 10%), severe fatigue (51% vs 41%), and symptoms of anxiety (36% vs 25%) or depression (36% vs 24%). Furthermore, proxies reported lower quality of life scores on most of the subdomains and PCS of the SF-36. No differences were found in cognitive functioning and SF-36 MCS (Supplemental Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/CCM/F584).

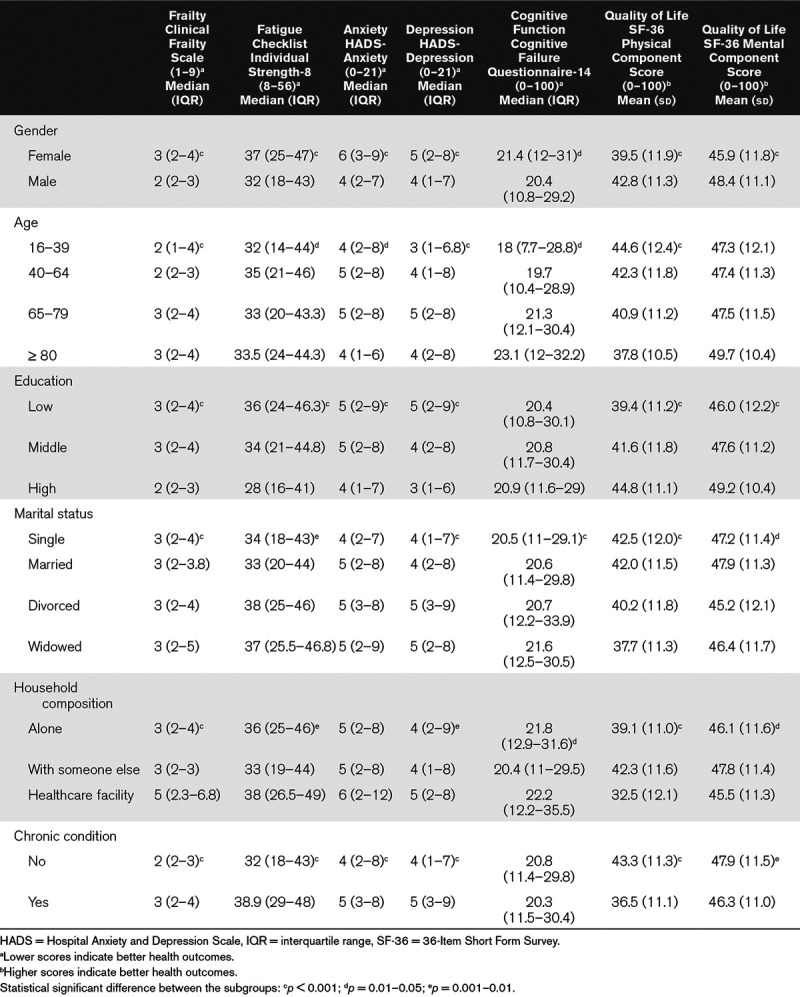

Other Subgroups.

Significant differences in pre-ICU health status and quality of life were also seen between subgroup of patients (Table 3). In general, patients with a poor health status and lower quality of life before ICU admission were more often female, older, lower educated, divorced or widowed, living in a healthcare facility, and suffering from a chronic condition.

TABLE 3.

Differences Between Subgroups in Pre-ICU Physical, Mental, and Cognitive Health Status and Quality of Life

DISCUSSION

In this large cohort study of ICU survivors, we showed that before ICU admission, 13% of the patients was already frail, 65% suffered from fatigue, and 28% and 26% from symptoms of anxiety and depression, respectively. Six percent experienced problems in their cognitive functioning. Patients with a poor pre-ICU health status were more likely to be female, older, lower educated, divorced or widowed, living in a healthcare facility and suffering from a chronic condition. Substantial differences were seen between patients with a planned and unplanned ICU admission.

Whereas previous studies often assessed one specific pre-ICU health outcome, for example, cognitive functioning (13, 27) or quality of life (28, 29), we assessed patient’s physical, mental, and cognitive functioning, as well as the quality of life, thereby providing a more complete picture of the pre-ICU health status. However, rates of pre-ICU frailty, anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment are lower compared with other studies (13, 17, 27, 40, 41). This may be explained by differences in inclusion criteria: in other studies, only elderly patients (13, 27) or medical patients with an ICU LOS of more than 48 hours (41) were included. Nevertheless, quality of life is in line with previous studies (28, 29, 42, 43) and significantly lower than the quality of life experienced by the general Dutch population (44). The patient subgroups that experience a worse pre-ICU health status are consistent with those reported in other studies as well (21, 27, 28).

Implication for Clinical Practice

In recent decades, the key question in intensive care medicine has changed from “‘Will my patient survive or die” into “How will my patient survive” (45). However, the use of accurate ICU prognostic models, such as the APACHE-IV or Simplified Acute Physiology Scores, is not sufficient to answer this question: they predict short-term survival (46), but are unable to predict important outcomes for ICU survivors, namely physical, mental, and cognitive functioning; return to work; and quality of life in the months and years following ICU discharge (47, 48).

“Study the past if you would define the future” proclaimed Confucius. Insight in patients’ pre-ICU health status is paramount. First of all because it could support clinical decision-making and set shared treatment goals (46, 49–51). Besides, patients and their relatives can be better informed about possible long-term outcomes based on their functional status before admission (16, 52). Second, it helps to identify specific types of patients who are at risk for specific long-term problems and could benefit from preventive interventions (13, 15). For example, long-term mental health problems following ICU admission could be modifiable if distressed patients are identified and receive treatment early (53), including psychologic support, education, and coping strategies (54). And third, accounting for the pre-ICU health status is important for assessing the impact of critical illness and ICU exposure on long-term outcomes. Failing to account for preexisting diseases and comorbidities before ICU admission may overestimate the attributable effect of critical illness and ICU stay (19, 25, 55). Besides, it could improve the evaluation of interventions (14, 56) because it is plausible that subgroup of patients respond differently to interventions (14).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, half of the patients completed the questionnaire after ICU admission, recalling their health status before admission. Although this was the only way we could assess the pre-ICU health status in patients with an unplanned admission, it could have led to recall bias, potentially leading to an overestimation of baseline function (24, 55). Second, 20% of the questionnaires were completed by proxies, showing significantly worse outcomes in frailty, fatigue, anxiety, and depression, compared with questionnaires completed by patients themselves. The usefulness and reliability of proxies assessments could be criticized because their perception of baseline status could differ from the patient (28, 55). On the other hand, studies have demonstrated that proxies are able to reliably assess patient’s pre-ICU quality of life (42, 57). The alternative, excluding patients who are unable to complete the questionnaire by themselves, also introduced bias (28). And third, the question is whether commonly used standardized outcome measures, such as the SF-36 and HADS, adequately reflect patients’ experiences. A previous study, in which standardized outcome measures were compared with findings from qualitative interviews, concluded that it is reliable to use standardized outcome measures for physical and mental health impairment (58). However, they emphasized that caution is needed in interpreting self-reported cognitive function. Additionally, a recent published study found no clinically relevant correlation between subjective and objective cognitive function, highlighting thereby the complexity of cognitive function testing. In our study, cognitive impairment rates were lower than expected and it is likely that these rates were an underestimation (59).

CONCLUSIONS

In an era with increasing attention for health problems after ICU admission, the results of this study indicate that a part of the ICU survivors already experience impairments in their physical, mental, and cognitive functioning before their ICU admission. More than half of the patients suffered from fatigue and a quarter from symptoms of anxiety and depression. A lower proportion was frail or cognitive impaired. Substantial differences in impairment rates were seen between patient subgroups. These findings underline the importance of accounting for the health status before ICU admission when studying long-term outcomes in ICU patients.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge all the patients and their relatives for their participation in this study. Furthermore, we thank the ICU staff of the Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital (Nijmegen), Bernhoven Hospital (Uden), Jeroen Bosch Hospital (‘s-Hertogenbosch), and Radboud University Medical Center (Nijmegen) for their contribution to this study.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal).

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harvey MA, Davidson JE. Postintensive care syndrome: Right care, right now…and later. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44:381–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu A, Gao F. Long-term outcomes in survivors from critical illness. Anaesthesia. 2004; 59:1049–1052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: Report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med. 2012; 40:502–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowan K, Jenkinson C, Black N. Angus DC, Carlet J. Health-related quality of life. In Surviving Intensive Care. 2004, Berlin, Springer-Verlag, pp 35–50 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jutte JE, Erb CT, Jackson JC. Physical, cognitive, and psychological disability following critical illness: What is the risk?. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2015; 36:943–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Svenningsen H, Langhorn L, Agard AS, et al. Post-ICU symptoms, consequences, and follow-up: An integrative review. Nurs Crit Care. 2017; 22:212–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill AD, Fowler RA, Pinto R, et al. Long-term outcomes and healthcare utilization following critical illness—A population-based study. Crit Care. 2016; 20:76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brummel NE, Balas MC, Morandi A, et al. Understanding and reducing disability in older adults following critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2015; 43:1265–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brummel NE, Bell SP, Girard TD, et al. Frailty and subsequent disability and mortality among patients with critical illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017; 196:64–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Myers EA, Smith DA, Allen SR, et al. Post-ICU syndrome: Rescuing the undiagnosed. JAAPA. 2016; 29:34–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubenfeld GD. Interventions to improve long-term outcomes after critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007; 13:476–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuthbertson BH, Wunsch H. Long-term outcomes after critical illness. The best predictor of the future is the past. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016; 194:132–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrante LE, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, et al. Pre-intensive care unit cognitive status, subsequent disability, and new nursing home admission among critically ill older adults. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018; 15:622–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith DM, Salisbury LG, Lee RJ, et al. ; RECOVER Investigators Determinants of health-related quality of life after ICU: Importance of patient demographics, previous comorbidity, and severity of illness. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas B, Wunsch H. How does prior health status (age, comorbidities and frailty) determine critical illness and outcome?. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016; 22:500–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oeyen S, Vermeulen K, Benoit D, et al. Development of a prediction model for long-term quality of life in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2018; 43:133–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muscedere J, Waters B, Varambally A, et al. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017; 43:1105–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidet B, de Lange DW, Boumendil A, et al. ; VIP2 Study Group The contribution of frailty, cognition, activity of daily life and comorbidities on outcome in acutely admitted patients over 80 years in European ICUs: The VIP2 study. Intensive Care Med. 2020; 46:57–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orwelius L, Nordlund A, Nordlund P, et al. Pre-existing disease: The most important factor for health related quality of life long-term after critical illness: A prospective, longitudinal, multicentre trial. Crit Care. 2010; 14:R67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabiee A, Nikayin S, Hashem MD, et al. Depressive symptoms after critical illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2016; 44:1744–1753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bagshaw SM, Stelfox HT, McDermid RC, et al. Association between frailty and short- and long-term outcomes among critically ill patients: A multicentre prospective cohort study. CMAJ. 2014; 186:E95–E102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latronico N, Herridge M, Hopkins RO, et al. The ICM research agenda on intensive care unit-acquired weakness. Intensive Care Med. 2017; 43:1270–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azoulay E, Vincent JL, Angus DC, et al. Recovery after critical illness: Putting the puzzle together—A consensus of 29. Crit Care. 2017; 21:296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abelha FJ, Santos CC, Barros H. Quality of life before surgical ICU admission. BMC Surg. 2007; 7:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubenfeld GD. Does the hospital make you older faster?. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012; 185:796–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pietiläinen L, Hästbacka J, Bäcklund M, et al. Premorbid functional status as a predictor of 1-year mortality and functional status in intensive care patients aged 80 years or older. Intensive Care Med. 2018; 44:1221–1229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pisani MA, Inouye SK, McNicoll L, et al. Screening for preexisting cognitive impairment in older intensive care unit patients: Use of proxy assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003; 51:689–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, et al. Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2005; 60:332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graf J, Koch M, Dujardin R, et al. Health-related quality of life before, 1 month after, and 9 months after intensive care in medical cardiovascular and pulmonary patients. Crit Care Med. 2003; 31:2163–2169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geense W, Zegers M, Vermeulen H, et al. MONITOR-IC study, a mixed methods prospective multicentre controlled cohort study assessing 5-year outcomes of ICU survivors and related healthcare costs: A study protocol. BMJ Open. 2017; 7:e018006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geense W, Zegers M, Dieperink P, et al. Changes in frailty among ICU survivors and associated factors: Results of a one-year prospective cohort study using the Dutch Clinical Frailty Scale. J Crit Care. 2020; 55:184–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rockwood K, Song X, MacKnight C, et al. A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ. 2005; 173:489–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vercoulen JH, Swanink CM, Fennis JF, et al. Dimensional assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1994; 38:383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983; 67:361–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wassenaar A, de Reus J, Donders ART, et al. Development and validation of the abbreviated Cognitive Failure Questionnaire in intensive care unit patients: A multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2018; 46:79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ponds R, Boxtel M, Jolles J. The Cognitive Failure Questionnaire as measure for subjective cognitive functioning [Dutch]. Tijdschrift voor Neuropsychologie. 200637–42 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992; 30:473–483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware JE, Jr, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. 2005Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Klundert N, Holman R, Dongelmans DA, et al. Data resource profile: The Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) Registry of admissions to adult intensive care units. Int J Epidemiol. 2015; 44:1850–1850h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.González-Martín S, Becerro-de-Bengoa-Vallejo R, Angulo-Carrere MT, et al. Effects of a visit prior to hospital admission on anxiety, depression and satisfaction of patients in an intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019; 54:46–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wewalka M, Warszawska J, Strunz V, et al. Depression as an independent risk factor for mortality in critically ill patients. Psychosom Med. 2015; 77:106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gifford JM, Husain N, Dinglas VD, et al. Baseline quality of life before intensive care: A comparison of patient versus proxy responses. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38:855–860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dinglas VD, Gifford JM, Husain N, et al. Quality of life before intensive care using EQ-5D: Patient versus proxy responses. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41:9–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998; 51:1055–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bein T, Bienvenu OJ, Hopkins RO. Focus on long-term cognitive, psychological and physical impairments after critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2019; 45:1466–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hofhuis JG, Spronk PE, van Stel HF, et al. Quality of life before intensive care unit admission is a predictor of survival. Crit Care. 2007; 11:R78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dinglas VD, Chessare CM, Davis WE, et al. Perspectives of survivors, families and researchers on key outcomes for research in acute respiratory failure. Thorax. 2018; 73:7–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wysham NG, Abernethy AP, Cox CE. Setting the vision: Applied patient-reported outcomes and smart, connected digital healthcare systems to improve patient-centered outcomes prediction in critical illness. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014; 20:566–572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de Jonge E, Mooijaart SP. Framework to decide on withholding intensive care in older patients. Neth J Crit Care. 2019; 27:150–154 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bukan RI, Møller AM, Henning MA, et al. Preadmission quality of life can predict mortality in intensive care unit—A prospective cohort study. J Crit Care. 2014; 29:942–947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krinsley JS, Wasser T, Kang G, et al. Pre-admission functional status impacts the performance of the APACHE IV model of mortality prediction in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2017; 21:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parry SM, Huang M, Needham DM. Evaluating physical functioning in critical care: Considerations for clinical practice and research. Crit Care. 2017; 21:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davydow DS, Zatzick D, Hough CL, et al. A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms over the course of the year following medical-surgical intensive care unit admission. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013; 35:226–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peris A, Bonizzoli M, Iozzelli D, et al. Early intra-intensive care unit psychological intervention promotes recovery from post traumatic stress disorders, anxiety and depression symptoms in critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2011; 15:R41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Needham DM, Dowdy DW, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Studying outcomes of intensive care unit survivors: Measuring exposures and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2005; 31:1153–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Geense WW, van den Boogaard M, van der Hoeven JG, et al. Nonpharmacologic interventions to prevent or mitigate adverse long-term outcomes among ICU survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2019; 47:1607–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hofhuis J, Hautvast JLA, Schrijvers AJP, et al. Quality of life on admission to the intensive care: Can we query the relatives?. Intensive Care Med. 2003; 29:974–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nelliot A, Dinglas VD, O’Toole J, et al. Acute respiratory failure survivors’ physical, cognitive, and mental health outcomes: Quantitative measures versus semistructured interviews. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019; 16:731–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Brück E, Larsson JW, Lasselin J, et al. Lack of clinically relevant correlation between subjective and objective cognitive function in ICU survivors: A prospective 12-month follow-up study. Crit Care. 2019; 23:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.