Abstract

This paper compares today’s corporate management in developing markets (BRICS countries) vs. developed markets (the OECD countries). The influence of determining a new social corporate management season considering social distancing amid the COVID-19 pandemic on emerging markets' economic growth is ascertained and set apart from corporate management in developing markets. This paper helps clarifying and better understanding the role of corporate social responsibility in the conditions of an economic crisis against the background of the COVID-19 pandemic. This work provides scientific arguments that allow solving critical discussions regarding the advantages (growth of quality of life, an increase of business's competitiveness) and costs (limitation of economic growth, non-commercial use of profit, and increased price for goods and services) of domestic production and consumption. In the long-term, responsible financial practices return all investments and allow countries to better cope with a crisis. The research supplies a new view of corporate social responsibility as a measure of crisis management. It reflects its advantages at a time of social distancing in the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The institutionalization of corporate social responsibility in emerging countries is not predetermined by internal factors (approach to doing business or organizational culture), if not by external factors (market status, state regulation, and consumer awareness). These circumstances prove the high complexity of strengthening corporate social responsibility in developing countries. In the conditions of social distancing – due to the COVID-19 pandemic – corporate social responsibility goes to a new level. In both developing and developed countries, one of the most widespread manifestations of corporate social responsibility is the entrepreneurship's transition to the remote form of activities. This envisages the provision of remote employment for workers and the online purchase of goods and services for consumers.

Keywords: Corporate Management, Institutionalization, Corporate Responsibility, Emerging Markets, Social Distancing, COVID-19

1. Introduction

In the current conditions of globalization and the COVID-19 pandemic, developing nations must compete not only with each other but also with developed markets. The most important goal for both categories of states is to promote the rate of economic growth, which reflects the competitiveness of domestic entrepreneurship. The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the lives of every individual and the economy. The pandemic has caused a shock to pulsate the global economy. Major countries, aside from China, where the virus originated, have displayed negative growth adaptation. As a result of this significant decline, the United Nations predicts that the foreign direct investment could drop to between 5 and 15 percent, hitting the lowest levels since the 2008 financial crisis.

Innovations that implement a plan of action can be the origin of long-term relief. Because of the evolution of stakeholder capitalism, businesses can gain a source of protection to promote economic growth in the workforce, even during challenging times. With positive corporate innovation strategies and help from companies worldwide, vulnerable developing nations can withstand the hit. CSR in emerging markets has the power to shape policy, benefit workers, and society as well as innovate products of shared value worldwide.

There is no question that the impact of COVID 19 is going protract. What is essential to discover in this research are the principles different firms are going to follow. The vulnerability that firms pose during this pandemic leaves challenging decisions regarding behavior and ethical reasoning. Unfortunately, in some instances, profiteering has been used as an advancement tactic. COVID 19 has given large companies the power to control their management regarding CSR in both positive and negative ways. Fortunately, many companies have stayed ethical concerning their CSR. With different countries offering relief aid packages, it allows flexibility even during uncertain times. Innovations that implement a plan of action can be the origin of long-term relief. Because of the evolution of stakeholder capitalism, businesses can gain a source of protection to promote economic growth in the workforce, even during challenging times. With positive corporate innovation strategies and help from companies worldwide, vulnerable developing nations can withstand the hit. CSR in emerging markets has the power to shape policy, benefit workers, and society as well as innovate products of shared value worldwide.

Based on differences in macro-economic conditions, we distinguish the factors of competitiveness of business and economic growth only from the state (e.g., the openness of economy or specifics of formation and spending of budget assets). Micro-economic factors of economic growth, related to peculiarities of corporate management, remain concealed. Incomplete reflection and consideration of economic growth elements cannot ensure a successful solution to the global scientific and practical problem of modern times, increasing inequality. The decline of reasonable attempts to solve this problem with the help of isolated management of macro-economic factors (budget deficit, national debt, direct foreign investments). According to the United Nations, different countries have adopted several strategies for sustainable development. Developing markets are successfully able to cope with these strategies because of the load put on private businesses. The government's role results in emerging markets to be impotent as far as the implementation of practical techniques. The first attempt at emulating international practices has not been cited in expected results, as the level of corporate responsibility in emerging markets still is inadequate.

The new context arising from the COVID-19 circumstances actualizes the issue of the search for new alternative means of enacting a better corporate responsibility in emerging markets. This article's working hypothesis is that the microeconomic factors of corporate management largely determine the economic growth of developing markets. The anomalies of developing markets define not only the first level of responsibility of business hold but also specifics of institutionalization. That is why it is especially important to analyze the details of corporate social responsibility in developing countries as compared to developed countries, as this will allow determining the optimal institutional approach to its implementation in the interests of crisis management. This research is to clarify the role of corporate social responsibility in the time of a crisis and its priorities, which will allow improving the practices of corporate management in developed and developing countries and overcoming the situation at a time of COVID-19. The specifics of institutionalization of corporate social responsibility in the context of social distancing amid the COVID-19 pandemic are studied in this paper.

2. Theoretical Background

Specifics of economic growth in countries with developing markets are in Bani & Kedir (2017), Bermúdez and Dabús (2018), Darku and Yeboah (2018), Fosu (2017), Lajili and Gilles (2018), Niebel (2018), Ochoa-Jimenez et al. (2018), Popkova et al. (2018), Sekiguchi (2017), Wu et al. (2018), and Zahonogo (2018). The present works describe the differences in developed and developing countries' economic growth through the prism of growth rate. It is higher in developing countries, but more stable in developed countries. Growth vectors in developed countries rely on innovations and hi-tech in developing countries. Traditions and quality of growth in developed countries accompanied by social progress, and in developing countries, it brings high social and ecological costs. However, causal connections of economic growth are studied insufficiently and are not determined by modern economic science, requiring further research. The issues of corporate management are explored in the works of such scholar as Al-Hadi et al. (2018), Bae et al. (2018), Ben-Hassoun et al. (2018), Bobillo et al. (2018), Gaitán et al. (2018), Jacometti et al. (2019), Keay and Zhao (2018), Marques et al. (2018), Marquis et al. (2017), Oh et al. (2018), Singareddy et al. (2018), and Thomsen (2016). The existing publications reflect the essence and methodological approaches to corporate management. Still, they do not show its contribution to the provision of economic growth, which considers being a derivative of state management.

Despite the prominent level of elaboration on these issues in existing publications, the differences in perspectives of corporate governance in developing markets, and their influence on the economic growth of these markets are insufficient. This gap is to be filled by this work. The conceptual foundations of studying the practice of corporate responsibility as a social institute stand in the works of Abney (2019), Ararat et al. (2018), Axjonow et al. (2018), Boyd and Huettinger (2019), Dey et al. (2018), Gond et al. (2018), Gordon (2020), Harjoto and Laksmana (2018), Hielscher and Kivimaa (2019), Huang and Fu (2019), Inshakova et al. (2018), Kail et al. (2017), Lahtinen et al. (2018), Luque and Herrero-García (2019), Nurunnabi et al. (2018), Pereira et al. (2019), Reilly and Larya (2018), Rim et al. (2019), Sun and Gunia (2018), Tsalis et al. (2018), Yen et al. (2019), Weber et al. 2019).

These works emphasize the importance and topicality of corporate responsibility in conditions of the modern market economy. Implementing voluntary initiatives for businesses to improve their employees' labor conditions and implementing socially significant projects creates a particular environmental protection sphere. Application of these practices on corporate responsibility in developing markets are found in the following readings: Benlemlih (2019), Borges et al. (2018), Cheong et al. (2017), Denisov et al. (2018), Ge and Zhao (2017), Gong and Ho (2018), Han and Zheng (2016), Krivtsov (2014), Lee et al. (2018), Li and Liu (2018), Malik and Kanwal (2018), Marquis et al. (2017), Morozova et al. (2018), Mukherjee et al. (2018), Nazri et al. (2018), Popkova (2017), Schrempf-Stirling (2018), and Veselovsky et al. (2018), Chu et al. (2018), Frig et al. (2018), Harjoto and Laksmana (2018)), Kansal et al. (2018), Sheikh (2019), Utgård (2018).

These articles emphasize the high complexity of implementing corporate responsibility practices in emerging markets, relating to the deficit of financial resources in businesses and the transformation of market economies. However, it distorts market stimuli for a responsible company.

Vodenko et al. (2018) and Volkov et al. (2017) relate specifically to the Russian National Model of economic activities within the neo-institutional theory. These articles reflect the Russian model's uniqueness in the market economy, which explicitly implements corporate responsibility. Despite the high-level elaboration on this topic, studies have been unsatisfactory. Abnormalities of institutionalization of corporate responsibility in developing markets compared to others are still unclear, requiring further systematic research.yandex.ru

3. Methodology

The research is based on the hypothetical and deductive principle and conducted in three consecutive stages. The first stage includes the determination of corporate management attributes in developing markets as compared to developed markets. The method of finding the average values of statistical data and the purpose of comparative analysis is precise. The second stage includes the purpose of the influence in peculiarities of corporate management on the economic growth of developing markets. For this, the method of multiple regression analysis is used. An optimization task for achieving the target (quick) value of the growth rate of economies of developing markets is solved according to the determined regression dependence with the help of the method of scenario analysis and optimization modeling. During the third stage, perspectives are acclaimed, and practical recommendations are given for the growth rate of developing markets using optimization of corporate management, based on the obtained solution to the optimization task.

4. Peculiarities of corporate management in developing markets

For determining the peculiarities of corporate management, the key indicators are studied that reflect the essential characteristics of entrepreneurial activities:

-

•

Shadowization of business: Index of the level of information opening, Companies that hide revenues from taxation, aggregate tax rate;

-

•

The rationality of personnel choice – Companies with a top female manager;

-

•

Legal protection of business: Companies conducting unofficial payments to government workers, Losses from stealing and vandalism, Index of the legal protection of business;

-

•

Accessibility of state services: Time spent on following state regulators' requirements, the average time required for starting a business, and the number of newly registered companies;

-

•

Reliability of infrastructural provision: Lost profit from electric supply failures, Index of the effectiveness of logistics;

-

•

The complexity of conducting foreign economic activities: Average time spent on import, Average time spent on export.

The 2018 indicators are selected according to the criterion of accessibility of information – World Bank's statistical databases; GDP growth at constant prices (IMF). The research objects are countries of BRICS, which present developing markets – Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa; and five countries of the OECD with developed countries – the USA, the UK, Australia, South Korea, and Japan.

This allowed covering all continents and excluding the geographic factor, thus receiving the most precise and authentic results of comparing developed and developing countries' data. The first statistical data are in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Indicators of economic growth and corporate management.

| Indicators | Brazil | Russia | India | China | South Africa | USA | UK | Australia | South Korea | Japan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index of the level of information opening, points 0 (lowest opening)-10(highest opening) | 5.0 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 8.0 | 7.4 | 10.0 | 8.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| Companies that hide revenues from taxation, % of companies | 51.4 | 40.7 | 59.2 | 49.5 | 40.3 | 28.4 | 32.7 | 25.6 | 43.7 | 24.1 |

| Companies conducting unofficial payments to government workers, % of companies | 12.5 | 20.5 | 16.6 | 10.7 | 15.1 | 5.6 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 14.0 | 6.3 |

| Losses from stealing and vandalism, % of annual sales of damaged companies | 6.9 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 |

| Time spent on following the requirements of state regulators, % of the time of companies' top management | 14.2 | 14.7 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 5.9 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Average time spent on import, days | 4.0 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Average time spent on export, days | 3.0 | 5.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Average time required for starting business, days | 79.5 | 10.1 | 29.8 | 22.9 | 45.0 | 5.6 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 12.2 |

| Companies with a top female manager, % of companies | 14.6 | 20.1 | 8.9 | 13.8 | 5.3 | 58.6 | 55.4 | 59.7 | 36.1 | 34.3 |

| Index of the legal protection of business points 0(weak)-12(strong) | 2.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 11.0 | 7.0 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Lost profit from electric supply failures, % of annual sales of damaged companies | 1.9 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Aggregate tax rate, % of companies’ commercial revenues | 68.4 | 47.5 | 55.3 | 67.3 | 28.9 | 43.8 | 30.7 | 47.5 | 33.1 | 47.4 |

| Number of newly registered companies | 18,393 | 433,464 | 93,714 | 1,534,982 | 376,727 | 987,346 | 663,616 | 246,623 | 96,155 | 11,886 |

| Index of the effectiveness of logistics, 1(low)-5(high) | 3.1 | 2.6 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Growth of GDP in constant prices, % | 1.748 | 1.444 | 7.685 | 6.168 | 1.569 | 2.519 | 1.457 | 2.999 | 2.835 | 0.586 |

Source: Compiled by the authors based on World Bank (2020) and International Monetary Fund (2020).

A comparison of developed and emerging markets envisages averaging the values of the given indicators. For obtaining the most precise average values, the following algorithm of their calculation is used:

-

•

Calculation of direct average for all five countries;

-

•

Determination of deviation of the values of each country from the direct average value;

-

•

Determination of the highest deviations (bold crossed);

-

•

Calculation of specified average values with the exclusion of the strongest deviations.

Results of the averaging indicators of corporate management in developed and developing markets are in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Averaging of indicators of corporate management.

| Indicators | Developing markets |

Developed markets |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | Deviation |

Specified average value | Average | Deviation |

Specified average value | ||||||||||

| Brazil | Russia | India | China | South Africa | USA | UK | Australia | South Korea | Japan | ||||||

| Index of the level of information opening, points 0 (lowest opening)-10(highest opening) | 7.40 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 1.08 | 1.35 | 1.08 | 7.40 | 7.88 | 0.94 | 1.27 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 7.88 | |

| Companies that hide revenues from taxation, % of companies | 48.21 | 1.07 | 0.84 | 1.23 | 1.03 | 0.84 | 48.21 | 30.89 | 0.92 | 1.06 | 0.83 | 1.41 | 0.78 | 30.89 | |

| Companies conducting unofficial payments to government workers, % of companies | 15.08 | 0.83 | 1.36 | 1.10 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 15.08 | 7.76 | 0.72 | 1.01 | 0.66 | 1.80 | 0.81 | 7.76 | |

| Losses from stealing and vandalism, % of annual sales of damaged companies | 3.10 | n/a | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.77 | 2.15 | 0.18 | 1.11 | 0.56 | 1.11 | 1.67 | 0.56 | 0.18 | |

| Time spent on following the requirements of state regulators, % of the time of companies’ top management | 7.52 | 1.89 | 1.95 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.78 | 7.52 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.10 | |

| Average time spent on import, days | 4.80 | 0.83 | 1.46 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.63 | 4.80 | 2.80 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 0.71 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 2.80 | |

| Average time spent on export, days | 3.60 | 0.83 | 1.39 | 1.11 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 3.60 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| Average time required for starting business, days | 37.46 | n/a | 0.27 | 0.80 | 0.61 | 1.20 | 26.95 | 5.76 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 0.43 | 0.69 | n/a | 4.15 | |

| Companies with a female top manager, % of companies | 12.54 | 1.16 | 1.60 | 0.71 | 1.10 | 0.42 | 12.54 | 48.82 | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.22 | 0.74 | 0.70 | 48.82 | |

| Index of the legal protection of business points 0(weak)-12(strong) | 5.40 | 0.37 | 1.48 | 1.48 | 0.74 | 0.93 | 5.40 | 7.80 | 1.41 | 0.90 | 1.41 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 7.80 | |

| Lost profit from electric supply failures, % of annual sales of damaged companies | 2.06 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 1.80 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 2.06 | 0.46 | 1.09 | 0.87 | 0.65 | 1.30 | 1.09 | 0.46 | |

| Aggregate tax rate, % of companies’ commercial revenues | 53.48 | 1.28 | 0.89 | 1.03 | 1.26 | 0.54 | 53.48 | 40.50 | 1.08 | 0.76 | 1.17 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 40.50 | |

| Number of newly registered companies | 491,456 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.19 | n/a | 0.77 | 230,574 | 401,125 | n/a | 1.65 | 0.61 | 0.24 | 0.03 | 254,570 | |

| Index of the effectiveness of logistics, 1(low)-5(high) | 3.30 | 0.94 | 0.79 | 1.03 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 3.30 | 3.86 | 1.01 | 1.06 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 1.01 | 3.86 | |

Source: authors' calculations.

It is necessary to compare the average values of corporate management indicators in developing markets to average values of these indicators in developed markets and to determine their differences (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

The ratio of indicators of corporate management in developed and developing markets.

| Characteristics of entrepreneurial activities | Indicators | The average value for developing countries/ The average value for developed countries |

|---|---|---|

| Shadowization of business | Index of the level of information opening points 0 (lowest opening)-10(highest opening) | 0.94 |

| Companies that hide revenues from taxation, % of companies | 1.56 | |

| Aggregate tax rate, % of companies’ commercial revenues | 1.32 | |

| The rationality of personnel selection | Companies with a top female manager, % of companies | 0.26 |

| Legal protection of business | Companies conducting unofficial payments to government workers, % of companies | 1.94 |

| Losses from stealing and vandalism, % of annual sales of damaged companies | 11.94 | |

| Index of the legal protection of business, points 0(weak)-12(strong) |

0.69 | |

| Accessibility of state services | Time spent on following the requirements of state regulators, % of the time of companies' top management | 75.20 |

| Average time necessary for starting business, days | 6.49 | |

| Number of newly registered companies | 0.91 | |

| Reliability of infrastructural provision | Lost profit from electric supply failures, % of annual sales of damaged companies | 4.48 |

| Index of the effectiveness of logistics, 1(low)-5(high) |

0.85 | |

| The complexity of conducting foreign economic activities | Average time spent on import, days | 1.71 |

| Average time spent on export, days | 1.80 |

Source: authors' calculations.

It is Simplest to present the obtained results in the form of a polygon of corporate management competitiveness in developing markets. The average values of corporate governance indicators in developed markets will be considered models and equal 1; the ratio of corporate management indicators in emerging markets and the model values are determined.

The indicators that characterize corporate management positively (e.g., the index of the level of information opening), are compared by finding the values of developing markets to the values of developed markets (direct ratio). On the contrary, the indicators that characterize corporate management negatively (e.g., companies that hide revenues from taxes) are compared by finding ratios of the values of developed markets to the values of developing markets (reverse ratio). For each characteristic, a direct average of the values of the corresponding indicators is found. The obtained results are as follows in developing markets:

-

•

Forced shadowization of business, caused by a low level of information on entrepreneurial activities and hiding revenues from taxation due to high tax level; however, it slightly (22%) exceeds shadowization of business in developed markets – 0.78;

-

•

The irrationality of personnel selection is related to people occupying offices in the company not based on their competence but on personal motives of management, which leads to age, gender, and other inequality of employees; it is by 74% less rational than in developing markets – 026;

-

•

More active risk management due to a low level of the legal protection of business, related to forced corruption (unofficial payments to government employees), losses from stealing and vandalism, and legal vulnerability (non-observation of the terms of concluded contracts); it is much (by 57%) lower than with developed markets – 0.43;

-

•

Low flexibility and mobility of business due to low accessibility of state services, which is caused by a large volume of time spent for following the state's requirements, which leads to low business activity (smaller number of registered companies); it is much (by 64%) lower than in developed markets – 0.36;

-

•

Non-optimality of business processes due to low reliability of infrastructural provision of business, which is related to the lost cost of business due to failures in electric energy supply and ineffectiveness of logistics; it is much (by 46%) lower than in developed markets – 0.54;

-

•

Forced orientation at internal (domestic) markets due to the complexity of foreign economic activities, which is caused by substantial volumes of time spent for import and export; it is much (by 43%) lower than in developed markets – 0.57.

These peculiarities show that the competitiveness of business in developing markets is much smaller (on average, by 51%) than in developed markets. Such sharp differences cannot but influence economic growth. It is most practical and simplest to conduct an in-depth analysis of the influence of corporate management's peculiarities on the developing markets' economic growth.

5. Influence of corporate management on the economic growth of developing markets

The regression analysis results of the dependence of economic growth on indicators of corporate governance in developing markets are shown in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Results of regression analysis of the dependence of economic growth on indicators of corporate management in developing markets.

| Variables | Coefficients регрессии | Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Growth GDP in constant prices | Y-crossing | 3.9137309 |

| Index of the level of information opening | Variable at x1 | 0 |

| Companies that hide revenues from taxation | Variable at x2 | 0 |

| Companies conducting unofficial payments to government workers | Variable at x3 | 0 |

| Losses from stealing and vandalism | Variable at x4 | 0 |

| Time spent on following the requirements of state regulators | Variable at x5 | −0,425496 |

| Average time spent on import | Variable at x6 | 0 |

| Average time spent on export | Variable at x7 | 0 |

| Average time required for starting a business | Variable at x8 | −0.047691 |

| Companies with a top female manager | Variable at x9 | 0 |

| Index of the legal protection of business | Variable at x10 | 0 |

| Lost profit from electric supply failures | Variable at x11 | 0 |

| Aggregate tax rate | Variable at x12 | 0.1127774 |

| Number of newly registered companies | Variable at x13 | −2.52E-06 |

| Index of the effectiveness of logistics | Variable at x14 | 0 |

Source: authors' calculations.

The data in Table 4 show that the following factors predetermine the GDP growth in constant prices in the countries with developing markets (y):

-

•

time spent on following the requirements of state regulators (x5 – reverse dependence);

-

•

average time required for starting a business (x8 – reverse dependence);

-

•

aggregate tax rate (x12 – direct dependence);

-

•

the number of newly registered companies (x13 – reverse dependence).

The function of the determined regression dependence has the following form: y = 3.9137309-0.425496*x5-0.047691*x8+0.1127774*x12-2.52E-06*x13. This means that when the time spent on following state regulators' requirements increases by 1%, the rate of economic growth increases by 0.42%. When the average time required for starting a business increases by 1 day, the rate of economic growth increases by 0.04%. When the aggregate tax rate increases by 1%, the rate of economic growth increases by 0.11%. When the number of newly registered companies increases by 1 percent, the rate of economic growth is virtually unchanged (the regression coefficient tends to zero).

A high correlation of 99.99% (tends to 100%) shows the reliability of the compiled regression model.

The growth rate of the global economy constituted 3.152% in 2017. The average growth rate of the economy of countries with developing markets represented 3.723% in 2017, which is higher than the average global level. However, this is not enough for overcoming the underrun from the countries with developed markets – for this; emerging markets should have a growth rate of the economy that is at least twice as high as the present one – i.e., 7.446% (3.723%*2).

This allows formulating the conditions of the optimization task that is solved automatically in Microsoft Excel:

-

•

target function: multiple regression dependence y(x5, x8, x12, x13), should constitute 7.446;

-

•

variables: x5, x8, x12, x13;

-

•

limitations: x5≥3.76, x8≥18.73, x12≤69.52, x13≥344,019 – are to ensure the achievability of optimization values of the variables in practice. For this, optimization values x5 and x8 should not be lower than the current values by more than 50%; optimization value x12 should not be higher than its current level by more than 30%, and optimization value x13 should not be lower than its current level by more than 30%).

As a result, we received the following values of variables that ensure optimization of the target function (achievement of growth of the economy of countries with forming markets by 7.446% per year on average):

-

•

x5 = 5.18 - time spent for following the requirements of state regulators should be reduced by 68%;

-

•

x8 = 25.99 - average time required for starting a business should be reduced by 68%;

-

•

x12 = 69.52 - aggregate tax rate should be increased by 30;

-

•

x13 = 344,019 - The number of newly registered companies should be increased by 69%.

6. Perspectives and recommendations for accelerating the growth rate of developing markets on the optimization of corporate management

Macroeconomic conditions in which business is functioning determine the peculiarities of corporate management, including in developing markets. A more robust growth rate in emerging markets requires implementing complex and interconnected measures at the national and organizational levels. The following mechanism of accelerating the growth rate of developing markets through optimization of corporate management is offered. The structure of accelerating growth in emerging markets through the optimization of corporate governance is implemented based on a two-stage algorithm. The first stage is creating a favorable institutional environment for the development of business by performing the following measures at the state level:

-

•

Increase of legal protection of business (development of contractual law);

-

•

Increase of accessibility of state services (development of E-government);

-

•

Increase of reliability of infrastructural provision of business (investments into the infrastructure);

-

•

Simplification of conducting foreign economic activities (reduction of customs barriers).

This will establish favorable conditions for manifestations of corporate social responsibility, an increased rate of economic growth, and accelerated recovery from the COVID-19 crisis.

The above measures aim to prepare macro-economic conditions for future micro-level changes related to the optimization of corporate management.

The second stage includes the modernization of business based on the latest information and communication technologies and the optimization of corporate management by online marketing. The state stimulates the creation of new companies (through information & consultation and credit & subsidy support for entrepreneurial initiatives of the population) and nominal and gradual growth of the level of business taxation.

Also, a possibility supports simple electronic registration and accounting of online business and a reduction of requirements from the state to online marketing. This becomes possible since online business, unlike traditional, does not require premises, equipment, and, secondly, needs only a small number of employees. There is no need to verify the observation of complex sanitarium and epidemiological and other requirements that are usually before traditional business.

Also, the online form of doing business envisages its maximum transparency and, therefore, a state control. This allows for full automatization of online business and state interaction, including online document turnover and online corporate accounting. Thus, it is possible to perfect corporate management, which will have the following features:

-

•

maximum openness (de-shadowization);

-

•

the rationality of personnel selection;

-

•

minimum risk management;

-

•

increased flexibility and mobility of business;

-

•

optimality of business processes;

-

•

expansion of markets of sales and supplies (development of foreign economic activities).

As a result, the growth of business activity and the increase of business competitiveness in developing markets will be ensured, as well as the state's tax revenues. This will provide resources for further state stimulation of the economy's development and stimulate future economic growth of developing markets. However, in social distancing conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth of business activity will be slow. The actions of most companies with a traditional form of organization contradict the idea of remote realization of goods and services, and consumers – under the influence of government requirements and/or own preferences (danger of infection) – avoid social interactions. Therefore, corporate social responsibility amid the COVID-19 pandemic should aim at the flexible growth of business activity given new consumer preferences and the transformation of business in a remote form, which envisions the slight realization of products.

7. Overview of the practice of corporate responsibility in developing markets

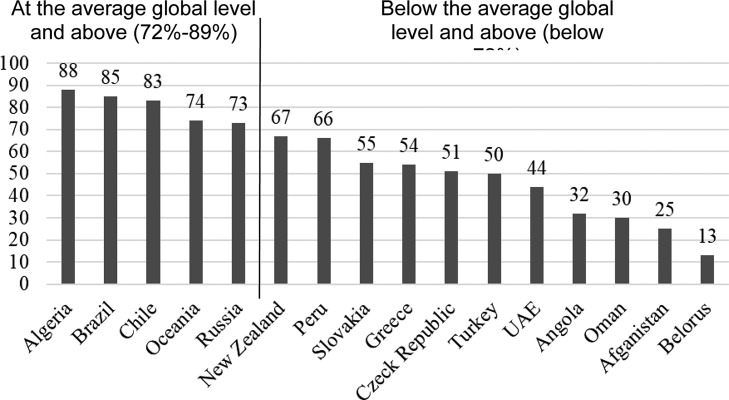

Developed markets compared to undeveloped markets demonstrate a free-access report on corporate responsibility. As seen in Fig. 1 , most developing markets in 2018 are on the lower side, sitting below the global average (72%). We can see that the average global level for Nigeria is 88%, Brazil 85%, Chile 83%, Romania 74%, and Russia at 72%. Most countries stay above an average of 72%. We can see clearly that countries like Sweden, Canada, Australia, and Germany remain at higher levels based on the corporate responsibility shown in their open-access reports.

Fig. 1.

Ranking of developing markets with the distribution of free-access reports on corporate responsibility in 2018.

Source: Compiled by the authors (McRitchie, 2018).

An important note to consider in emerging markets is government requirements shown in the open-access reports. Notably, high efficiency reflects on large businesses that dominate the economy of developing markets. Russia, which traditionally specializes in oil and gas production, holds high levels of open-access corporate responsibility reports, as practice in this field is mandatory. In 2018, the oil and gas industry was ranked first among all economic spheres to distribute open-access reports on corporate responsibility (81%) (McRitchie, 2018).

The second issue is the separation of corporate responsibility from core businesses. In developing markets, access reports are published separately from corporate financial statements, compared to in developed markets; corporate responsibility is published in key corporate reports. For example, 81% of businesses in the United States publish information on corporate responsibility in their corporate financial statements. In the UK, Denmark, 86% is present. In Mexico, integrated reports are 21% of businesses and 15% in Poland. Russia lingers behind with less than 5%.

Additionally, corporate responsibility is a formality for most business structures. However, in 2018, only five businesses from Brazil, four from India, four from Russia and two from Mexico, and one from Saudi Arabia entered the global ranking of 250 enterprises that showed high corporate responsibility. France only held twenty, as well as ten from the UK and 18 from Germany (McRitchie, 2018).

Lastly, we concluded that the volume of corporate financing responsibility is low. In 2018, the leading share of global investments placed by businesses accounted for $22,890.14 billion in developed markets. Western European countries accounted for the following: Western-Europe ($10,039.57 billion), USA ($8,723.22 billion), Canada ($1,085.97 billion), Australia, and New Zealand ($515.73 billion) and Japan ($473.57 billion)—all information taken from annual KPMG Report. Overall, investment in business structures of developed markets amounted to $2,052.08 billion (8.96%).

These features show that the practice of corporate responsibility is evident in emerging markets. Thisshould influence the institutionalization of this practice, making it more visible in large businesses. At the same time, financing of the measures of corporate responsibility characterizes them only indirectly – as it shows only that investment resources are allocated for conducting the planned actions. Depending on the specific features of business taxation, financing of responsibility could take the form of tax optimization, i.e., reducing the tax liabilities of companies. That is why the data of corporate reports – especially large companies – could be formal and supply little information. However, they show that corporate responsibility is one of the integral components of doing business in developing markets, as it receives regular financing.

In the conditions of social distancing caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, a perspective direction of development of corporate social responsibility is the transfer of employees to a remote form of working and organization of the remote interaction between a company, consumers, and other concerned parties (e.g., investors, creditors, and state regulators). Digital technologies open broad perspectives for improving the practices of corporate social responsibility in the conditions of social distancing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, virtual and alternate reality technologies allow consumers to select products that usually require social interactions and visits to stores (e.g., clothing or footwear).

It is necessary to develop a legal framework for the regulation of entrepreneurship in developing countries for the successful implementation of recommendations made. It is Simplest to adopt national standards for the preparation and submission of corporate social responsibility reports. In the conditions of social distancing caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, corporate social responsibility reporting standards should include such indicators as enabling employees to work remotely and achieving a higher level of sanitation in workplaces that cannot be converted to remote working. In addition, standards should require that corporate social responsibility reporting be necessarily made available to the public on the internet. Corporate social responsibility reporting in the conditions of social distancing caused by the COVID-19 pandemic should be monitored and controlled using smart technologies (Artificial Intelligence) to achieve full monitoring coverage. E-government is the most effective approach to regulation.

8. Conclusions

Evidence shows that the duration of the state's involvement in responsible business must stay involved throughout the process, which cannot happen if there are market regulation terms. Therefore, this paper offers the concept of quick finishing for the operation of responsibility in developing markets. Regarding interested parties, this regulation envisages the formation of the culture of responsible consumption, business cooperation, and growth of employees' labor awareness. This will allow solving the real contradiction and harmonizing business interests related to the refusal of corporate responsibility and ignoring the needs and requirements of interested parties. A new task for the state is to search for flexible mechanisms of indirect regulation by creating favorable and stimulating conditions for implementation. This shows the necessity for public monitoring and control over corporate accountability with the involvement of independent—e.g., audit, expert, and analytical—companies.

Peculiarities of corporate management (i.e., micro-economic factors) predetermine the differences between developed and developing markets. Adverse global economic circumstances at the time of COVID-19 and changing macro-economic environment leads to reinforcing anomalies of corporate management in emerging markets. We have found such as forced shadowization of business, the irrationality of personnel choice, and more active risk management. Additionally, expenditures and lack of pricing competitiveness due to a low level of the legal protection of activity, little flexibility and mobility of business due to low accessibility of public services, non-optimality of business processes due to low reliability of infrastructural provision of business, and forced orientation at internal (domestic) markets due to complexity of conducting foreign economic activities.

A new growth rate envisions corporate management's optimization by reducing time spent for the execution of state's requirements and paid for starting a business, growth of tax load on business, and growth of the number of created companies in developing markets. Perspectives of this optimization envisage initial improvement of the macro-economic environment for doing business, for which it is recommended to build E-government. At the micro-level, it requires an intensification of online business development with the corresponding state stimuli. Also creating maximum openness, the rationality of personnel selection, minimum risk management, increased flexibility and mobility of company, optimality of business processes, and development of different economic activities.

Although low requirements for corporate responsibility are set in the emerging world, our findings show insufficient marketing tactics, little consumer awareness, and the workforce's weak power. Responsible business culture is not evident, but it would require righting shadowization and implementing standards of reports on corporate responsibility. Successful implementation of this concept will allow making the practice of corporate responsibility extremely popular and finish the process of institutionalization in developing markets.

In light of social distancing caused by the COVID-19 pandemic corporate social responsibility goes to a new level. In both developing and developed countries, one of the most widespread manifestations of corporate social responsibility is the entrepreneurship’s transition to the remote form of activities. This envisages provision of remote employment for workers and online purchase of goods and services for consumers.

Authors statemen

All authors contributed equally to the submitted paper.

References

- Abney K. Ethics of colonization: Arguments from existential risk. Futures. 2019;110:60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hadi A., Al-Yahyaee K.H., Hussain S.M., Taylor G. Market risk disclosures, corporate governance structure and political connections: evidence from GCC firms. Applied Economics Letters. 2018;25(19) 1346-135. [Google Scholar]

- Ararat M., Colpan A.M., Matten D. Business Groups and Corporate Responsibility for the Public Good. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;2(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Axjonow A., Ernstberger J., Pott C. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Corporate Reputation: A Non-professional Stakeholder Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;151(2):429–445. [Google Scholar]

- Bae S.M., Masud M.A.K., Kim J.D. A cross-country investigation of corporate governance and corporate sustainability disclosure: a signaling theory perspective. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2018;10(8):11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Bani Y., Kedir A. Growth, volatility and education: Panel evidence from developing countries. International Journal of Economics and Management. 2017;11(1):225–235. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Hassoun A., Aloui C., Ben-Nasr H. Demand for audit quality in newly privatized firms in MENA region: role of internal corporate governance mechanisms audit. Research in International Business and Finance. 2018;45(1):34–348. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez C., Dabús C. Going under to stay on top: How much real exchange rate undervaluation is needed to boost growth in developing countries | [Bajando para permanecer en la cima: Cuánta subvaluación del tipo de cambio real se necesita para impulsar el crecimiento de las economías en desarrollo] Estudios de Economia. 2018;45(1):5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bobillo A.M., Rodríguez-Sanz J.A., Tejerina-Gaite F. Corporate governance drivers of firm innovation capacity. Review of International Economics. 2018;26(3):721–741. [Google Scholar]

- Borges M.L., Anholon R., Cooper Ordoñez R.E., (…), Santa-Eulalia L.A., Leal Filho W. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices developed by Brazilian companies: an exploratory study. International Journal of Sustainable Development and World Ecology. 2018;25(6):509–517. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd J.A., Huettinger M. Smithian insights on automation and the future of work. Futures. 2019;111:104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Chu A.M.Y., So M.K.P., Chung R.S.W. Applying the Randomized Response Technique in Business Ethics Research: The Misuse of Information Systems Resources in the Workplace. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;151(1):195–212. [Google Scholar]

- Darku A.B., Yeboah R. Economic openness and income growth in developing countries: a regional comparative analysis. Applied Economics. 2018;50(8):855–869. [Google Scholar]

- Denisov I.V., Khachaturyan M.V., Umnova M.G. Corporate social responsibility in Russian companies: Introduction of social audit as assurance of quality. Quality - Access to Success. 2018;19(164):63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Dey P.K., Petridis N.E., Petridis K. (…), Nixon J.D., Ghosh S.K. Environmental management and corporate social responsibility practices of small and medium-sized enterprises. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018;195(1):687–702. [Google Scholar]

- Fosu A.K. Growth, inequality, and poverty reduction in developing countries: Recent global evidence. Research in Economics. 2017;71(2):306–336. [Google Scholar]

- Frig M., Fougère M., Liljander V., Polsa P. Business Infomediary Representations of Corporate Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;151(2):337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gaitán S., Herrera-Echeverri H., Pablo E. How corporate governance affects productivity in civil-law business environments: Evidence from Latin America. Global Finance Journal. 2018;37:173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ge J., Zhao W. Institutional Linkages with the State and Organizational Practices in Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from China. Management and Organization Review. 2017;13(3):539–573. [Google Scholar]

- Gond J.-P., Cabantous L., Krikorian F. How do things become strategic? ‘Strategifying’ corporate social responsibility. Strategic Organization. 2018;16(3):241–272. [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Ho K.-C. Does corporate social responsibility matter for corporate stability? Evidence from China. Quality and Quantity. 2018;52(5):2291–2319. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon A.V. Matrix purpose in scenario planning: Implications of congruence with scenario project purpose. Futures. 2020;115:102479. [Google Scholar]

- Han Y., Zheng E. Why Firms Perform Differently in Corporate Social Responsibility? Firm Ownership and the Persistence of Organizational Imprints. Management and Organization Review. 2016;12(3):605–629. [Google Scholar]

- Harjoto M., Laksmana I. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Risk Taking and Firm Value. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;151(2):353–373. [Google Scholar]

- Hielscher S., Kivimaa P. Governance through expectations: Examining the long-term policy relevance of smart meters in the United Kingdom. Futures. 2019;109:153–169. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.-Y., Fu C.-J. Constructing a system for effective implementation of strategic corporate social responsibility. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. 2019;773(1):862–866. [Google Scholar]

- Inshakova A.O., Frolov D.P., Davydova M.L., Marushchak I.V. Institutional Factors of Evolution and Strategic Development of General Purpose Technologies. Espacios. 2018;39(1):5–8. [Google Scholar]

- International Monetary Fund . 2020. Gross domestic product, constant prices: Report for Selected Countries and Subjects [Cited 26 July 2020.]http://www.imf.org Available from URL: [Google Scholar]

- Jacometti M., Lago E.C.W., Oliveira A.G., Oliveira L.C., Bonfim L.R.C. Best practices of corporate governance in a network of tourism firms in Brazil. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering. 2019;505:870–876. [Google Scholar]

- Kail Ya.Ya., Zudina E.V., Epinina V.S., Bakhracheva Y.S., Velikanov V.V. Effective HR-management as the most important condition of successful business administration. Integration and Clustering for Sustainable Economic Growth. Contributions to Economics. 2017;2(1):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kansal M., Joshi M., Babu S., Sharma S. Reporting of Corporate Social Responsibility in Central Public Sector Enterprises: A Study of Post Mandatory Regime in India. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;151(3):813–831. [Google Scholar]

- Keay A., Zhao J. Transforming corporate governance in Chinese corporations: A journey, not a destination. Northwestern Journal of International Law and Business. 2018;38(2):187–232. [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov A.I. Strategic analysis of external environment as a basis for risks assessment. Actual Problems of Economics. 2014;160(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lahtinen S., Kuusela H., Yrjölä M. The company in society: when corporate responsibility transforms strategy. Journal of Business Strategy. 2018;2(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Lajili O., Gilles P. Financial liberalization, political openness and growth in developing countries: Relationship and transmission channels. Journal of Economic Development. 2018;43(1):1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.H., Byun H.S., Park K.S. Product market competition and corporate social responsibility activities: Perspectives from an emerging economy. Pacific Basin Finance Journal. 2018;49(1):60–80. [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Liu C. Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Cost of Equity Capital: Lessons from China. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade. 2018;54(11):2472–2494. [Google Scholar]

- Luque A., Herrero-García N. How corporate social (ir)responsibility in the textile sector is defined, and its impact on ethical sustainability: an analysis of 133 concepts. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. 2019;26(6):1285–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Malik M.S., Kanwal L. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Financial Performance: Case Study of Listed Pharmaceutical Firms of Pakistan. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;150(1):69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Marques T.A., de Sousa Ribeiro K.C., Barboza F. Corporate governance and debt securities issued in Brazil and India: A multi-case study. Research in International Business and Finance. 2018;45:257–270. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis C., Yin J., Yang D. State-mediated globalization processes and the adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting in China. Management and Organization Review. 2017;13(1):167–191. [Google Scholar]

- McRitchie J. 2018. Global Sustainable Investment Review: Global Sustainable Investment Up 25%https://www.corpgov.net/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Global-Sustainable-Investment-Data-1.png URL: [Google Scholar]

- Morozova I.A., Popkova E.G., Litvinova T.N. Sustainable development of global entrepreneurship: infrastructure and perspectives. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal. 2018;2(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Bird R., Duppati G. Mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility: The Indian experience. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics. 2018;14(3):254–265. [Google Scholar]

- Nazri M.A., Omar N.A., Mohd Hashim A.J. Corporate social responsibility and market orientation: An integrated approach towards organizational performance. Jurnal Pengurusan. 2018;52(1):75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Niebel T. ICT and economic growth – comparing developing, emerging and developed countries. World Development. 2018;104(1):197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nurunnabi M., Alfakhri Y., Alfakhri D.H. Consumer perceptions and corporate social responsibility: what we know so far. International Review on Public and Nonprofit Marketing. 2018;15(2):161–187. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-Jimenez D., Moreno-Hurtado C., Ochoa-Moreno W.-S. Vol. 2. 2018. Economic growth and internet access in developing countries: the case of South America | [Crecimiento económico y el acceso a internet en países en vías de desarrollo: El caso de América del Sur] pp. 18–22. (Iberian Conference on Information Systems and Technologies, CISTI). 1. [Google Scholar]

- Oh W.-Y., Chang Y.K., Kim T.-Y. Complementary or Substitutive Effects? Corporate Governance Mechanisms and Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Management. 2018;44(7) 2716-273. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira P., Cortez M.C., Silva F. Socially responsible investing and the performance of Eurozone corporate bond portfolios. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. 2019;26(6):1407–1422. [Google Scholar]

- Popkova E.G. Information Age Publishing; Charlotte (North Carolina), USA: 2017. Economic and Legal Foundations of Modern Russian Society: A New Institutional Theory. Advances in Research on Russian Business and Management. [Google Scholar]

- Popkova E.G., Bogoviz A.V., Pozdnyakova U.A., Przhedetskaya N.V. Specifics of economic growth of developing countries. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control. 2018;135:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly A.H., Larya N. External Communication About Sustainability: Corporate Social Responsibility Reports and Social Media Activity. Environmental Communication. 2018;12(5):621–637. [Google Scholar]

- Rim H., Kim J., Dong C. A cross-national comparison of transparency signaling in corporate social responsibility reporting: The United States, South Korea, and China cases. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. 2019;26(6):1517–1529. [Google Scholar]

- Schrempf-Stirling J. State Power: Rethinking the Role of the State in Political Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;150(1):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi N. Trade specialisation patterns in major steelmaking economies: the role of advanced economies and the implications for rapid growth in emerging market and developing economies in the global steel market. Mineral Economics. 2017;30(3):207–227. [Google Scholar]

- Singareddy R.R.R., Chandrasekaran S., Annamalai B., Ranjan P. Corporate governance data of 6 Asian economies (2010–2017) Data in Brief. 2018;20(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X., Gunia B.C. Economic resources and corporate social responsibility. Journal of Corporate Finance. 2018;51(1):332–351. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen S. The nordic corporate governance model. Management and Organization Review. 2016;12(1):189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Tsalis T.A., Stylianou M.S., Nikolaou I.E. Evaluating the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of occupational health and safety disclosures. Safety Science. 2018;109(1):313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Utgård J. Retail chains’ corporate social responsibility communication. Journal of Business Ethics. 2018;147(2):385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Veselovsky M.Y., Izmailovа M.A., Bogoviz A.V., Lobova S.V., Ragulina Y.V. System approach to achieving new quality of corporate governance in the context of innovation development. Quality - Access to Success. 2018;19(163):30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vodenko L.V., Rodionova V.I., Shvachkina L.A., Shubina M.M. Russian national model for the regulation of social and economic activities: research methodology and social reality. Quality-Access to Success. 2018;19(S2):141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Volkov Yu. V., Vodenko K.V., Lubsky A.V., Degtyarev A.K., Chernobrovkin I.P. Russia is Searching for Models of National Integration and the Possibility to Implement Foreign Experience. Information. 2017;20(7A):4693–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Weber K.M., Gudowsky N., Aichholzer G. Foresight and technology assessment for the Austrian parliament—finding new ways of debating the future of industry 4.0. Futures. 2019;109:240–251. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2020. Indicators: Private Sector [Cited 26 July 2020.]https://data.worldbank.org/indicator Available from URL: [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y., Zhu Q., Zhu B. Comparisons of decoupling trends of global economic growth and energy consumption between developed and developing countries. Energy Policy. 2018;116(1):30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yen M.-F., Shiu Y.-M., Wang C.-F. Socially responsible investment returns and news: evidence from Asia. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. 2019;26(6):1565–1578. [Google Scholar]

- Zahonogo P. Globalization and Economic Growth in Developing Countries: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. International Trade Journal. 2018;32(2):189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Benlemlih M. Corporate social responsibility and dividend policy. Research in International Business and Finance. 2019;47:114–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong C.W.H., Sinnakkannu J., Ramasamy S. Reactive or proactive? Investor sentiment as a driver of corporate social responsibility. Research in International Business and Finance. 2017;42:572–582. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh S. Corporate social responsibility and firm leverage: The impact of market competition. Research in International Business and Finance. 2019;48:496–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ribaf.2018.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- Spence David B. Vol. 59. 2011. https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol86/iss1/4 (Corporate Social Responsibility in the Oil and Gas Industry: The Importance of Reputational Risk, 86 Chi.-Kent L. Rev.). Available at: [Google Scholar]

- Fifkaa S. Matthias, and Csr. “An Institutional Approach to Corporate Social Responsibility in Russia”. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2014;(8 July) www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652614006799 Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Ghoneim Mo. Forbes, Forbes Magazine. 2019. Why Corporate Social Responsibility Matters.www.forbes.com/sites/forbescommunicationscouncil/2019/06/14/why-corporate-social-responsibility-matters/#1df0132032e1 14 June, [Google Scholar]

- Kotova Maria, Shira Dezan, Associates Moscow . Russia Briefing News. 2020. The Social & Economic Impact of Covid-19 On Russia And Recovery Potential.www.russia-briefing.com/news/social-economic-impact-covid-19-russia-recovery-potential.html/ 13 Apr. [Google Scholar]

- KPMG . 2018. The road ahead: The KPMG Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting 2017.http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/kpmg-survey-of-corporate-responsibility-reporting-2017.pdf URL: [Google Scholar]

- McPherson Susan. Forbes, Forbes Magazine. 2019. Corporate Responsibility: What to Expect In 2019.www.forbes.com/sites/susanmcpherson/2019/01/14/corporate-responsibility-what-to-expect-in-2019/#39427f43690f 16 Jan. [Google Scholar]

- (PDF) Corporate social responsibility in the oil and gas sector. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247577729_Corporate_social_responsibility_in_the_oil_and_gas_sector (Accessed 27 October 2019).

- Valet Vicky. Forbes, Forbes Magazine. 2018. The World’s Most Reputable Companies for Corporate Responsibility 2018.www.forbes.com/sites/vickyvalet/2018/10/11/the-worlds-most-reputable-companies-for-corporate-responsibility-2018/#2ec6b6433371 11 Oct. [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradov Alexander. The Moscow Times. 2019. B2B: Corporate Social Responsibility in Russia.www.themoscowtimes.com/2013/09/02/b2b-corporate-social-responsibility-in-russia-a27298 9 Oct. [Google Scholar]