Abstract

Background

This report aims to describe changes that centres providing transient ischaemic attack (TIA) pathway services have made to stay operational in response to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Methods

An international cross-sectional description of the adaptions of TIA pathways between 30th March and 6th May 2020. Experience was reported from 18 centres with rapid TIA pathways in seven countries (Australia, France, UK, Canada, USA, New Zealand, Italy, Canada) from three continents.

Results

All pathways remained active (n = 18). Sixteen (89%) had TIA clinics. Six of these clinics (38%) continued to provide in-person assessment while the majority (63%) used telehealth exclusively. Of these, three reported PPE use and three did not. Five centres with clinics (31%) had adopted a different vascular imaging strategy.

Conclusion

The COVID pandemic has led TIA clinics around the world to adapt and move to the use of telemedicine for outpatient clinic review and modified investigation pathways. Despite the pandemic, all have remained operational.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Ischemic Attack, Transient, Delivery of Health Care, Telemedicine

Introduction

The novel corona virus 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak is now classified as a pandemic.1 Unlike the recent viral H1N1 pandemic (also known as swine flu) in 2009, this pandemic has led to widespread disruption of society and has overwhelmed health care systems in some countries with a high level of infection. As part of ongoing preparatory measures, many health services have been reducing or ceasing ‘non-urgent care’, with impacts on secondary stroke prevention and urgent outpatient follow-up being one of the many potential adverse outcomes.2 In addition, due to concerns about use of needed supplies and hospital beds, even the evaluation of patients with acute neurological problems, like stroke and TIA, has been affected.

Urgent evaluation of TIA in the outpatient or ED setting has been successful in providing urgent care and preventing stroke occurrence.3 , 4 These rapid care pathways have grown based on earlier ‘natural history’ work showing a high risk of stroke at 90 days post TIA. With urgent evaluation and medical treatment, the risk of recurrent stroke has been reduced from 10.3% to 2.1% in some settings.3 A narrative survey of these innovative models of care illustrated their value in providing better health outcomes and reduction in healthcare costs.5 Furthermore, these rapid TIA clinics can potentially assist the healthcare system during this crisis. Management of patients in the outpatient setting can facilitate patient flow and allows inpatient resource and beds to be utilised for other purposes. The aim of this report is to provide a description of existing rapid TIA pathways around the world and understand the necessary adjustments in practice required to optimally evaluate and manage TIAs during the pandemic.

Methods

Study design

An international, multicentre, cross-sectional study to describe the adaptions of TIA pathways in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study was approved as a Quality Assurance activity (reference number: QA/63676/MonH-2020-209422) by the Monash Health Human Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was not required.

Participants

To identify our collaborators, we performed a literature review of rapid TIA pathways in PubMed. The search code was: ("transient ischaemic attack"[All Fields] OR "transient ischemic attack"[All Fields] OR TIA[All Fields])AND ("ambulatory care facilities"[MeSH Terms] OR ("ambulatory"[All Fields] AND "care"[All Fields] AND "facilities"[All Fields]) OR "ambulatory care facilities"[All Fields] OR "clinic"[All Fields] OR pathway[All Fields] OR "outpatients"[MeSH Terms] OR "outpatients"[All Fields] OR "outpatient"[All Fields] OR "triage"[MeSH Terms] OR "triage"[All Fields]) AND ("2000/01/01"[PDAT]: "2020/12/31"[PDAT] AND "humans"[MeSH Terms]). Additional records not captured by the search strategy were found by searching reference lists of published papers. Choice of publication was based on the description of a structured pathway from primary care and/or the emergency department to a dedicated TIA clinic that was aimed at expediting the evaluation and initial management of TIA. Review papers, surveys of practice, and tests of diagnostic accuracy were excluded. Audits of existing services against national targets, and models that introduced more aggressive secondary prevention strategies but did not include a rapid pathway were excluded. Two independent researchers (A.L and T.P) reviewed all articles meeting inclusion criteria. Final choice of included centres was by consensus.

Variables

Three demographic variables were noted – continent, pathway setting (hospital, ED, GP), and lockdown status. Lockdown status was measured based on the New Zealand Government alert system definition, with four tiers of increasing restriction – 1 = prepare, 2 = reduce, 3 = restrict, 4 = lockdown.6 Four adaptation variables were noted – whether a centre was active, whether a centre retained in-person assessment, if so, was PPE use reported, and whether brain and arterial imaging strategy was changed. Date of response and national COVID prevalence 7 , 8 on the 28th of April 2020 was also recorded. Non-responder data were extracted from the published article and included pathway setting, assessment method (in-person or telemedicine), and imaging choice. For these, clinic status (active versus non-active) was inferred by visiting the institution's website, and the date of the internet search was recorded.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive statistics to describe the findings.

Results

Participants and demographics

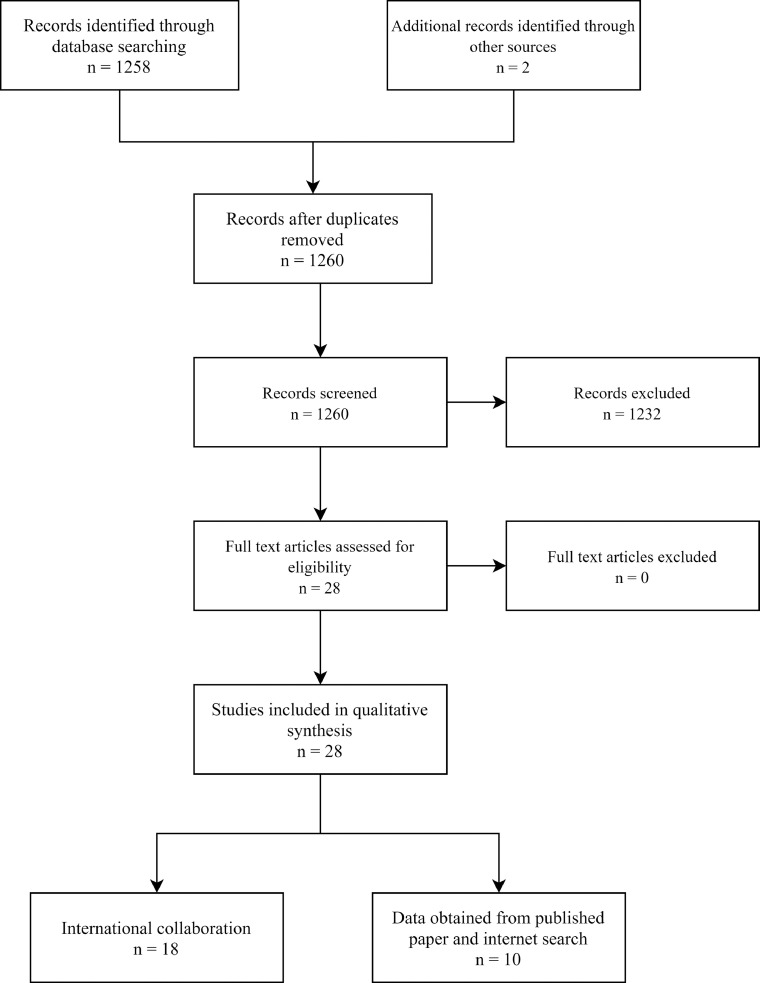

The PRISMA statement and the reasons for excluding studies are provided in Fig. 1 . A total of 1258 potential papers were identified in the PubMed search strategy. An additional two pathways were added from searching article reference lists.9 , 10 After searching 1260 titles and/or abstracts, 28 studies/pathways were selected. The final collaboration reported experience from eighteen centres in seven countries (Australia, France, UK, Canada, USA, New Zealand, Italy, Canada) from three continents (Oceania, Europe, North America).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of study.

Key results

Table 1 displays key results. The responses range from 30th March 2020 to 6th May 2020. All eighteen pathways reported remaining active. Six of the sixteen centres with TIA clinics (38%) continued to provide in-person assessment 3 , 4 , 9 , 11, 12, 13 while the others (63%) have changed their patient assessment method to exclusively telephone or video-enabled visit. Of these, three (Paris, Oxford, Leicester) reported PPE use and three (Wellington, Adelaide, Sydney) did not. Five centres with clinics (31%) adopted a different vascular imaging strategy.3 , 14, 15, 16, 17

Table 1.

TIA pathway adaptations.

| Pathway | City | Country | Setting | Region Lockdown status | Post-COVID-Assessment? | PPE use | Pre-COVID-Imaging | Post-COVID-Imaging – vascular strategy changed? | Date of response (2020) | National COVID prevalence (per million) * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M3T 14 | Melbourne | Australia | Hospital | 3 | Telephone | NA | CT/US | Yes - CTA | 8/4 | 0.56 |

| SOS-TIA 4 | Paris | France | Hospital | 3 | In-person | Yes | MRI/US | No† | 10/4 | 24.32 |

| Oxford Vascular Study 3 | Oxford | UK | Hospital | 3 | Telephone ± in-person | Yes | MRI/US | Yes - MRI/CTA | 30/3 | 68.29 |

| Ottawa 15 | Ottawa | Canada | Hospital | 4 | Telephone | NA | CT/US/CTA | Yes - CT/CTA | 12/4 | 44.16 |

| TWO-ACES 19 | Stanford | USA | Hospital | 3 | Video | NA | MRI/US | No | 17/4 | 86.62 |

| Rochester 18 | Rochester | USA | ED | 3 | Video outpatient clinic | NA (yes later) | CT/US/TEE for cardiac imaging | No‡ | 25/4 | 86.62 |

| Wellington 9 | Wellington | New Zealand | GP-Hospital | 4 | Telephone screen ± in-person | No | CT/US | No | 16/4 | 0.50 |

| Edinburgh 36 | Edinburgh | UK | Hospital | 3 | WhatsApp/Facetime/Telephone | NA | CT/MR/US | No | 11/4 | 68.29 |

| Tauranga 10 | Tauranga | New Zealand | Hospital | 4 | Telephone | NA | CT/MR/US | No | 12/4 | 0.50 |

| Adelaide 11 | Adelaide | Australia | Hospital | 3 | Telephone ± in-person | No | CT/CTA/D2-7 MR | No | 08/4 | 0.56 |

| RNSH 12 | Sydney | Australia | Hospital | 3 | Telephone ± in-person | No | CT/CTA/US/MRI | No | 20/4 | 0.56 |

| Glasgow 16 | Glasgow | UK | Hospital | 3 | Telephone | NA | CT/CTA/US | Yes - CT/CTA | 18/4 | 68.29 |

| BEATS 13 | Leicester | UK | Hospital | 3 | In-person | Yes | MRI/CT/US | No | 22/4 | 68.29 |

| RAVEN 17 | New York | USA | Hospital | 4 | Video visit (telehealth); Telephone if patient has no enabled device | NA | CT/US | Yes - CTA§ | 24/4 | 86.62 |

| Bologna 34 | Bologna | Italy | Hospital | 3 | Telephone | NA | CT/US/CTA | No | 24/4 | 42.97 |

| Foothills Medical Centre 35 | Calgary | Canada | Hospital | 3 | Telephone | NA | CTA | No | 6/5 | 44.16 |

| Grand Rapids 32 | Grand Rapids | USA | ED | 4 | Does not have a TIA clinic | NA | US/CTA/MRA | No | 11/4 | 86.62 |

| Boston 33 | Boston | USA | ED | 4 | Does not have a TIA clinic | NA | MRA/CTA+/-TTE | No | 23/4 | 86.62 |

PPE = personal protective equipment, M3T = Monash TIA Triaging Treatment, CT = computed tomography, CTA = computed tomography angiography, US = carotid ultrasonography, NA = not applicable, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography, D2-7 = days 2 to 7, RNSH = Royal North Shore Hospital, RAVEN = Rapid Access Vascular Evaluation – Neurology, TTE = transthoracic echocardiography, TEE = transesophageal echocardiography. UK = United Kingdom. USA = United States of America.

= As at 28th April 2020. Source: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

= CT chest performed before MRI brain in suspected COVID cases

= Note cardiac CT/TTE replacing TEE

= MRI in ED if follow-up considered unlikely

In-person TIA clinic assessment

Six centres in Paris,4 Oxford,3 Wellington,9 Adelaide,11 Sydney,12 and Leicester 13 retained in-person assessments, but with modifications. A seventh centre in Rochester,18 Minnesota reported a plan to reinstate the in-person evaluation in follow-up to the initial ED evaluation in late April with patient and staff masking, and extensive patient COVID-19 screening. The SOS-TIA France model 4 allowed patients with or without suspicion of COVID-19 to be evaluated in the TIA clinic, with the patient and the staff wearing a surgical mask and the medical staff wearing a gown and surgical hat. Patients at low risk of COVID-19, defined as the absence of fever, respiratory symptoms, and known contacts, were assessed by medical staff wearing a surgical mask. Oxford 3 were reviewing patients in-person with PPE if TIA was likely. In the Wellington centre,9 patients who were deemed likely to have TIA after telephone screen were sent to a raid access community testing centre for a swab. The result is available within hours, and the patient is seen in the TIA clinic on the same day if COVID-19 negative. In Adelaide patients were seen in clinic if there was symptomatic carotid artery stenosis or the diagnosis had been revised to stroke after a review of the MRI scans, provided that there was no suspicion of COVID-19. Those with suspicion were redirected from the hospital entrance to the COVID clinic. In Sydney,12 if diagnostics were performed as an outpatient before TIA clinic appointment, video telehealth or phone consult was offered to discuss results and further management. Before being offered in-patient assessment, a series of COVID risk questions are asked. If the patient questionnaire is positive, they are redirected for testing instead. Leicester 13 was still seeing patients face-to-face, but were increasing their focus on triage and referral with occasional phone review. PPE use included goggles, surgical mask, apron, and gloves for seeing inpatients, and goggles and surgical mask for outpatients with no symptoms.

Imaging protocol

The centres in Melbourne,14 Oxford,3 Ottawa,15 Glasgow 16 and New York 17 have largely replaced carotid ultrasonography with computed tomography angiogram (CTA). Mayo,18 New York,17 Paris,4 and Stanford 19 also reported additional imaging variations. At Mayo,18 for a short period in late March and April 2020, cardiac CT and transthoracic echocardiogram were used as short-term replacement for transoesophageal echocardiography (TEE) to lessen use of personal protective equipment (PPE) given that TEE is an aerosol generating procedure. The practice has now returned to use of TEE with appropriate PPE use. New York 17 additionally performs an MRI brain in the ED, as clinically indicated, if follow-up is considered unlikely. The SOS-TIA France model allowed patients to their TIA clinic. In case of suspected COVID infection the patients were screened with CT chest prior to MRI brain. Stanford TWO ACES model 19 admitted high risk TIA patients to facilitate MRI scanning; this change had occurred prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2 provides results from the ten centres that did not respond to the survey. The data were obtained from the published article and internet search. Six centres 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 appeared active based on their institutional website. None of the papers described telemedicine follow-up. Three of these pathways had CTA as an option for vascular imaging.21 , 22 , 24

Table 2.

Additional data from published article and internet search.

| City | Country | Continent | Setting | Pre-COVID-Assessment | Pre-COVID-Imaging | Clinic-Status on website | Date of internet search | National COVID-19 prevalence (per million) * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nantes 37 | Nantes | France | Europe | ED† | In-person† | CT in ED/US† | Does not specify | 28/4/20 | 24.32 |

| FAST TIA 20 | London | UK | Europe | Hospital† | In-person† | CT/US/TTE† | Active | 28/4/20 | 68.29 |

| Brechin 38 | Brechin | UK | Europe | GP-Hospital† | In-person† | CT/US† | Does not specify | 28/4/20 | 68.29 |

| Gosford/Wyong 21 | Gosford/Wyong | Australia | Eurasia | Hospital† | In-person† | CT/US/CTA† | Active | 28/4/20 | 0.56 |

| Halifax 22 | Halifax | Canada | North America | Hospital† | In-person† | CT/US/CTA/MRI/A† | Active | 28/4/20 | 44.16 |

| Munich 39 | Munich | Germany | Europe | Hospital† | In-person† | MRI/US† | Does not specify | 28/4/20 | 21.96 |

| Gloucestershire 23 | Gloucestershire | UK | Europe | Hospital† | In-person† | CT/US† | Active | 28/4/20 | 68.29 |

| RASP 24 | Dublin | UK | Europe | Hospital† | In-person† | CT/CTA/MRI/MRA/US† | Active | 28/4/20 | 68.29 |

| Rapid Access TIA 25 | London | UK | Europe | Hospital† | In-person† | Unknown | Active | 28/4/20 | 68.29 |

| Beijing 40 | Beijing | China | Asia | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Does not specify | 28/4/20 | <0.01 |

CT = computed tomography, CTA = computed tomography angiography, US = carotid ultrasonography, MRI = magnetic resonance imaging, MRA = magnetic resonance angiography, TTE = transthoracic echocardiography, RASP = Rapid Access Stroke Prevention

= As at 28th April 2020. Source: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

= From published article.

Discussion

This report regarding the adaptations of urgent TIA evaluation in response to the COVID-19 pandemic provides a description of the current international experience. The results cover eighteen centres across seven countries and three continents. The key findings were: (1) all participating centres remained operational, (2) change in assessment to telephone and/or video-enabled visits; (3) change in type of vascular imaging investigations,

First, the fact that all participating centres reported an active status suggests that the commitment that health services have made to redirecting TIA patients to rapid and/or outpatient pathways is significant. The ease of adoption did not seem to differ between jurisdictions, as all centres were able to adapt and remain active. This high operational status could be interpreted as a marker of the essential nature of this service, especially in a period of widespread elective surgical cancellations and shutdown of non-essential services worldwide. However, the seven countries represented (Australia, France, UK, Canada, USA, New Zealand, and Italy) all belong the upper quintile of the World Health Organization's universal health coverage index.26 Therefore, this could simply reflect a high level of health service resourcing.

Second, telemedicine has been recommended for the assessment of a patient with TIA during the pandemic - the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association have issued temporary guidance for the use of telemedicine for stroke care during this time.27 Similarly, the British National Health Service has also recommended this in order to reduce the need to use PPE for management of COVID-19 patients.28 While other countries may not have explicit guidance for TIA clinics, regulatory changes have supported the adoption of telemedicine.29 , 30 This is reflected in the change in pattern of practice seen in most centres. However, evidence is lacking regarding the safety of a TIA pathway via telemedicine. The downside to delivering care via telephone or a telemedicine platform is that patients may miss out on other aspects of secondary prevention such as blood pressure measurement and lipid management,31 in-person risk factor and lifestyle advice, driving issues, other diagnostic tests and timely prescription of medicine.3 These pathways were designed such that the TIA clinic component has in-person assessments with detailed neurological examination by a neurologist or stroke physician. This step is important as some patients may not have been evaluated by neurology or stroke physician staff at the ED presentation. For example, investigators have reported TIA mimics in 38.3% after evaluation in TIA clinic.14 The TIA clinics for non-admitted patients represent a significant step in confirming or refuting the diagnosis. Such evaluation can be difficult with telephone consultation especially for hearing impaired or patients with cognitive impairment. Given that these pathways have previously provided exclusively in-person assessments, this represents a significant shift in practice. This change does raise concerns regarding the quality of care that can be delivered and requires monitoring to evaluate the change in model of care on stroke recurrence.

Last, the imaging strategies during the COVID-19 era reflect local adaptation. Five centres replaced carotid ultrasonography with CT angiography.3 , 14, 15, 16, 17 These changes are not without precedents as eleven centres had already been performing CTA as a vascular imaging option in the pre-COVID era.11 , 12 , 15 , 16 , 21 , 22 , 24 , 32, 33, 34, 35 The changes in strategies may reflect the impracticality of bringing patients back for carotid ultrasound as a separate investigation.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, only published pathways were investigated. Therefore, our results may not reflect activity among other TIA clinics. Second, our reporting on the use of PPE as a binary variable is simplistic, as different health services have a range of PPE availability and utilization based on the procedure and setting. For instance, PPE use may imply a single surgical mask, or it may incorporate an N95 respirator, face shield, surgical gown, gloves, and hair net. Third, it remains uncertain how the COVID era has altered the patient demographics and number of patients referred for TIA clinic evaluation. Finally, we had described the 10 clinics in which we have tried to contact but have not received a written response. This data is described in separately in Table 2 to highlight that the data came from a different source and possibly less reliable as the websites may not have kept up to date with changes in the operational status of TIA clinics during the pandemic.

Conclusion

This study has provided an initial description of the global impact of COVID-19 on these pathways. These results reflect the recognition of TIA as a medical emergency, and treatment remains an essential health service, even if performed through telehealth. It will be important to perform a patient-level analysis of pre- and post- COVID clinical outcomes.

Declarations of Competing Interest

None

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to the physicians who spent time answering our survey.

AL is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

References

- 1.Kissler S.M., Tedijanto C., Goldstein E. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020 doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markus H.S., Brainin M. EXPRESS: COVID-19 and Stroke - a Global World Stroke Organisation perspective. Int. J. Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1747493020923472. In Press1747493020923472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rothwell P.M., Giles M.F., Chandratheva A. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet North Am Ed. 2007;370:1432–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61448-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavallée P.C., Meseguer E., Abboud H. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:953–960. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70248-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalanithi L., Tai W., Conley J. Better health, less spending: delivery innovation for ischemic cerebrovascular disease. Stroke. 2014;45:3105–3111. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.New Zealand Government. COVID-19 Alert System. 2020.

- 7.Roser M., Ritchie H., Ortiz-Ospina E., et al. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). 2020.

- 8.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Download today's data on the geographic distribution of COVID-19 cases worldwide. 2020.

- 9.Ranta A., Dovey S., Weatherall M. Cluster randomized controlled trial of TIA electronic decision support in primary care. Neurology. 2015;84:1545–1551. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddula M., Adams L., Donnelly J. From Inpatient to Ambulatory Care: The Introduction of a Rapid Access Transient Ischaemic Attack Service. Healthcare (Basel) 2018;6 doi: 10.3390/healthcare6020057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheong E., Toner P., Dowie G. Evaluation of a CTA-Triage Based Transient Ischemic Attack Service: A Retrospective Single Center Cohort Study. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27:3436–3442. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O'Brien E., Priglinger M.L., Bertmar C. Rapid access point of care clinic for transient ischemic attacks and minor strokes. J Clin Neurosci. 2016;23:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson A.D., Coleby D., Taub N.A. Delay between symptom onset and clinic attendance following TIA and minor stroke: the BEATS study. Age Ageing. 2014;43:253–256. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders L.M., Srikanth V.K., Jolley D.J. Monash transient ischemic attack triaging treatment: safety of a transient ischemic attack mechanism-based outpatient model of care. Stroke. 2012;43:2936–2941. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.664060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wasserman J., Perry J., Dowlatshahi D. Stratified, urgent care for transient ischemic attack results in low stroke rates. Stroke. 2010;41:2601–2605. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.586842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cameron A.C., Dawson J., Quinn T.J. Long-Term Outcome following Attendance at a Transient Ischemic Attack Clinic. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:306–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang B.P., Rostanski S., Willey J. Safety and feasibility of a rapid outpatient management strategy for transient ischemic attack and minor stroke: The Rapid Access Vascular Evaluation-Neurology (RAVEN) Approach. Ann Emerg Med. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stead L.G., Bellolio M.F., Suravaram S. Evaluation of transient ischemic attack in an emergency department observation unit. Neurocritical care. 2009;10:204. doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9146-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olivot J.-M., Wolford C., Castle J. Two aces: transient ischemic attack work-up as outpatient assessment of clinical evaluation and safety. Stroke. 2011;42:1839–1843. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.608380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banerjee S., Natarajan I., Biram R. FAST-TIA: a prospective evaluation of a nurse-led anterior circulation TIA clinic. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85:637–642. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.083162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffiths D., Sturm J., Heard R. Can lower risk patients presenting with transient ischaemic attack be safely managed as outpatients? J Clin Neurosci. 2014;21:47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosier G.W., Phillips S.J., Doucette S.P. Transient ischemic attack: management in the emergency department and impact of an outpatient neurovascular clinic. Cjem. 2016;18:331–339. doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutta D., Bowen E., Foy C. Four-year follow-up of transient ischemic attacks, strokes, and mimics: a retrospective transient ischemic attack clinic cohort study. Stroke. 2015;46:1227–1232. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.008632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradley D., Cronin S., Kinsella J.A. Frequent inaccuracies in ABCD2 scoring in non-stroke specialists' referrals to a daily rapid access stroke prevention service. J Neurol Sci. 2013;332:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Birns J., Vilasuso M., Cohen D.L. One-stop clinics are more effective than neurology clinics for TIA. Age Ageing. 2006;35:306–308. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afj057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 Global Monitoring Report. 2017.

- 27.Lyden P. Temporary emergency guidance to US stroke centers during the COVID-19 pandemic on behalf of the AHA/ASA Stroke Council Leadership. Stroke. 2020;10 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Specialty guides for patient management during the coronavirus pandemic Clinical guide for the management of stroke patients during the coronavirus pandemic 23 March 2020 Version 1 Updated 16 April with updates highlighted in yellow. In: NHS, editor. England: NHS; 2020.

- 29.Australian Stroke Coalition. Stroke care during the COVID-19 crisis: Statement from the Australian Stroke Coalition. 2020.

- 30.Webster P. Virtual health care in the era of COVID-19. Lancet North Am Ed. 2020;395:1180–1181. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30818-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amarenco P., Lavallee P.C., Monteiro Tavares L. Five-Year Risk of Stroke after TIA or Minor Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2182–2190. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brown M.D., Reeves M.J., Glynn T. Implementation of an emergency department-based transient ischemic attack clinical pathway: a pilot study in knowledge translation. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:1114–1119. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jarhult S.J., Howell M.L., Barnaure-Nachbar I. Implementation of a rapid, protocol-based TIA management pathway. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19:216. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2017.9.35341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guarino M., Rondelli F., Favaretto E. Short- and long-term stroke risk after urgent management of Transient Ischaemic Attack: The Bologna TIA Clinical Pathway. Eur Neurol. 2015;74:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000430810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jeerakathil T., Shuaib A., Majumdar S.R. The Alberta Stroke Prevention in TIAs and mild strokes (ASPIRE) intervention: rationale and design for evaluating the implementation of a province-wide TIA triaging system. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(Suppl A100):135–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graham C., Bailey D., Hart S. Clinical diagnosis of TIA or minor stroke and prognosis in patients with neurological symptoms: A rapid access clinic cohort. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montassier E., Lim T.X., Goffinet N. Results of an outpatient transient ischemic attack evaluation: a 90-day follow-up study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:970–975. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.09.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad M., Selwyn J., Gillanders I. The development and performance of a rapid-access neurovascular (TIA) assessment clinic in a rural hospital setting. Scott Med J. 2009;54:15–19. doi: 10.1258/rsmsmj.54.4.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hörer S., Schulte-Altedorneburg G., Haberl R.L. Management of patients with transient ischemic attack is safe in an outpatient clinic based on rapid diagnosis and risk stratification. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;32:504–510. doi: 10.1159/000331919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang X., Fan C., Jia J. The effect of transient ischemic attack clinical pathway. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;26:386–391. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13070171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]