Abstract

Introduction

Oncologic surgical extirpation, the mainstay of loco-regional disease control in breast cancer, is aimed at achieving negative margins and lymph node clearance. Even though axillary lymph nodal metastasis is a critical index of prognostication, establishing the impact of lymph node ratio (LNR) and adequate surgical margins on disease-specific survivorship would be key to achieving longer survival. This study examines the prognostic role of pN (lymph nodes positive for malignancy), LNR and resection margin on breast cancer survival in a tertiary hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Methods

We conducted a longitudinal cohort study of 225 patients with breast carcinoma, documented clinico-pathologic parameters and 5-year follow up outcomes – distant metastasis and survival. Chi-square test and logistic regression analysis were used to evaluate the interaction of resection margin and proportion of metastatic lymph nodes with patients’ survival. The receiver operating characteristic curve was plotted to determine the proportion of metastatic lymph nodes which predicted survival. The survival analysis was done using Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

Sixty (26.7%) patients of the patients had positive resection margins, with the most common immuno-histochemical type being Lumina A. 110 (49%) patients had more than 10 axillary lymph nodes harvested. The mean age was 48.6 ± 11.8 years. Tumour size (p = 0.018), histological type (p = 0.015), grade (p = 0.006), resection margin (p = 0.023), number of harvested nodes (p < 0.01), number of metastatic nodes (p < 0.001) and loco-regional recurrence (p < 0.01) are associated with survival. The overall 5-year survival was 65.3%.

Conclusion

Unfavourable survival outcomes following breast cancer treatment is multifactorial, including the challenges faced in the multimodal treatment protocol received by our patients.

Keywords: survival, breast cancer, Ibadan, axillary nodes, resection margins

Introduction

Female breast cancer, the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women and a leading cause of female cancer mortality, continues to witness a rising age-standardized incidence rate [1–3]. The findings from an Ibadan population-based cancer registry in 2012 showed an incidence rate of 52.0 per 100,000 [3]. They are typically late stage, high grade and hormone receptor negative, and these factors represent an aggressive phenotype [4, 5].

Late stage at presentation has been associated with increased risk of mortality, especially in Low- and middle-income countries where social factors play a pivotal role in timing of presentation as well as acceptance of orthodox treatment, including breast-conserving surgery and mastectomy [6–8]. While surgical extirpation continues to be the mainstay of loco-regional disease control by achieving negative margins and lymph node clearance, it is well documented that the nodal status at diagnosis significantly affects overall survival, with axillary lymph nodal metastasis being a critical index of prognostication [9–11]. Furthermore, lymph node ratio (LNR), defined as the proportion of harvested lymph nodes positive for malignancy to total resected nodes [12, 13], has been implicated as a key prognostic factor. High LNR has not only been associated with unfavourable survival outcomes, its prognostic effect is found to be superior to total number of nodes [11]. Although the goal of surgery in breast cancer is to extirpate both macroscopic and microscopic tumour presence, the presence of a positive resection margin necessitates adjuvant radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy [14–16]. The late stage of disease in our environment makes modified radical mastectomy more favourable to a breast conserving surgery since in these cases, aggressive local therapy ensures adequate surgical margins and can determine disease-specific survival [17]. It is hoped that the utilisation of such multimodal approach to breast cancer care would keep the 5-year survival rate in sub-Saharan Africa on the upward trend [18–20]. Therefore, an intensive multimodal approach to breast cancer care is key to achieving longer disease-free survival and overall survival times [10, 11].

This study examines the prognostic role of pN (lymph nodes positive for malignancy), LNR and resection margin on breast cancer survival in a tertiary health institution in Ibadan, Nigeria.

Methods

The study involved a longitudinal cohort of patients with breast carcinoma who underwent modified radical mastectomy or breast conserving surgery with axillary clearance at the Oncological Surgery Division of the University College Hospital, Ibadan, between December 2009 and December 2014. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ministry of Health, Oyo State, Nigeria.

Preoperative tissue diagnosis was obtained by core needle biopsy and disease staging was done with chest radiography, abdominal sonography and bone scintigraphy.

The breast and axillary specimens were examined by dedicated breast pathologists, specifically for histological type and grade, axillary nodal metastasis and resection margin (defined as negative or positive). While the aim of surgical extirpation is to achieve complete cancer removal with at least 1cm cuff of grossly normal tissue, microscopic presence of tumour at the edges of excised specimen or axillary tail as well as underlying pectoral fascia classifies the surgical resection margin as positive [17]. Immunohistochemistry was done to determine receptor status. Adjuvant therapy consisted of chemotherapy, radiation treatment, endocrine therapy, immunotherapy or a combination of these.

The patients were followed up via clinic visits for a maximum period of 5 years following the completion of treatment, and contact tracing was done through phone calls, especially when the patients failed to turn up for scheduled appointments. Outcomes of interest included distant metastasis and survival. Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (version 22; SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL). Descriptive statistics was used to examine the demographic and clinico-pathological profile of the patients. Chi-square test and logistic regression analysis were used to evaluate the interaction of resection margin and proportion of metastatic lymph nodes with patients’ survival. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted to determine the proportion of metastatic lymph nodes which predicted survival. The survival analysis was done using Kaplan–Meier method.

The statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 225 patients were recruited for the study. Table 1 shows their biodata. The mean age was 48.6 ± 11.8 years. Nearly half of the patients were civil servants.

Table 1. Biodata and Clinico-pathologic profile.

| Frequency n = 225 |

Percentage % |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age (48.6 ± 11.8) | ||

| < 35 years | 27 | 12.0 |

| 35–44 years | 64 | 28.4 |

| 45–54 years | 65 | 28.9 |

| 55–64 years | 45 | 20.0 |

| ≥ 65 years | 24 | 10.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Civil servant | 109 | 48.4 |

| Trader | 101 | 44 .9 |

| Farmer | 3 | 1.3 |

| Others | 12 | 5.3 |

| Breast cancer sidedness | ||

| Right | 104 | 46.2 |

| Left | 121 | 53.8 |

| Tumour size (cm) [6 (4)] | ||

| T0 (0cm) | 3 | 1.3 |

| T1 (≤2cm) | 12 | 5.3 |

| T2 ( 2.01–5cm) | 63 | 28.0 |

| T3 (>5cm) | 147 | 65.3 |

| Histological type | ||

| Invasive CA NOS | 203 | 90.2 |

| Invasive lobular CA | 13 | 5.8 |

| Phyllodes tumour | 3 | 1.3 |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) | 6 | 2.7 |

| Tumour grade | ||

| Low grade | 39 | 17.3 |

| Intermediate grade | 112 | 49.8 |

| High grade | 36 | 16.0 |

| Not stated | 38 | 16.9 |

| Resection margin | ||

| Free | 163 | 72.4 |

| Involved | 60 | 26.7 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.9 |

| Immunohistochemistry | ||

| Luminal A | 69 | 30.7 |

| Luminal B | 6 | 2.7 |

| Her-2-enriched | 2 | 9.3 |

| Triple negative | 35 | 15.6 |

| Not stated | 94 | 41.7 |

| Nature of surgery | ||

| MRM | 222 | 98.7 |

| Quadrantectomy + axillary clearance | 3 | 1.3 |

As shown in Table 1, the histopathologic grossing average tumour size was 6 cm from with two-third of patients having tumour sizes above 5 cm. Nine of every ten participants had invasive carcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS). The commonest tumour grade was the intermediate variety (49.8%; n = 112), followed by low-grade breast cancers. Almost all the participants underwent a modified radical mastectomy (99%; n = 222). Three patients who had pre-operative histology of malignant phyllodes tumour had clinically positive axillae and had dissection done.

The resection margin was free in 72% of patients with the most common immunohistochemical type being Lumina A, followed by the triple negative variety.

Majority of patients (49%; n = 110) had more than 10 axillary lymph nodes harvested with a mean 11 nodes (Table 2).

Table 2. Axillary lymph nodal status, adjuvant treatment and outcomes.

| Frequency (n = 225) |

Percentage (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Harvested nodes [8 (6)] | ||

| 0 | 12 | 5.3 |

| 1–3 | 31 | 13.8 |

| 4–9 | 72 | 32.0 |

| ≥10 | 110 | 48.9 |

| Metastatic Nodes [1 (4)] | ||

| 0 | 103 | 45.8 |

| pN1: 1–3 | 47 | 20.9 |

| pN2: 4–9 | 63 | 28.0 |

| pN3: ≥10 | 12 | 5.3 |

| Adjuvant therapy | ||

| None | 107 | 47.6 |

| Chemotherapy | 112 | 49.8 |

| Chemo + RTH | 3 | 1.3 |

| Tamoxifen | 3 | 1.3 |

| 5-year survival status | ||

| Alive | 147 | 65.3 |

| Dead | 63 | 28.0 |

| Unknown | 15 | 6.7 |

Nearly half of the patients (49.8%; n = 112) had an adjuvant chemotherapy alone whereas as high as 47.6% had no adjuvant care. As high as 28% mortality was recorded as shown in Table 2.

Survival

Tumour size (p = 0.018), histological type (p = 0.015), grade (p = 0.006), resection margin (p = 0.023), number of harvested nodes (p < 0.01), number of metastatic nodes (p < 0.001) and loco-regional recurrence (p < 0.01) are associated with survival (Table 3).

Table 3. Factors associated with survival.

| Alive | Dead | Chi-square (p-value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour size (cm) | |||

| 0 | 3 (100%) | 0 | 10.09 (0.018) |

| ≤2 | 9 (75%) | 3 (25%) | |

| 2.01–5 | 48 (84.2%) | 9 (15.8%) | |

| >5 | 87 (63%) | 51 (37%) | |

| Histological type | |||

| Invasive CA NOS | 125 (66.5%) | 63 (33.35%) | 10.53 (0.015) |

| Invasive lobular CA | 13 (100%) | 0 | |

| Phyllodes tumour | 3 (100%) | 0 | |

| Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) | 6 (100%) | 0 | |

| Tumour grade | |||

| Low grade | 21 (53.8%) | 18 (46.2%) | 10.34 (0.006) |

| Intermediate grade | 70 (68%) | 33 (32%) | |

| High grade | 27 (90%) | 3 (10%) | |

| Resection margin | |||

| Free | 112 (74.2%) | 39 (25.8%) | 5.19 (0.023) |

| Involved | 33 (57.9%) | 24 (42.1%) | |

| Evidence of recurrence | |||

| Yes | 138 (78%) | 39 (22%) | 34.04 (<0.01) |

| No | 9 (27.3%) | 24 (72.7%) | |

| Harvested nodes | |||

| 0 | 9 (100%) | 0 | 27.98 (<0.01) |

| 1–3 | 28 (90.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | |

| 4–9 | 33 (47.8%) | 36 (52.2%) | |

| ≥10 | 77 (76.2%) | 24 (23.8%) | |

| Metastatic nodes | |||

| 0 | 76 (80.9%) | 18 (19.1%) | 21.27 (<0.001) |

| 1–3 | 35 (74.5%) | 12 (25.5%) | |

| 4–9 | 33 (57.9%) | 24 (42.1%) | |

| ≥10 | 3 (25%) | 9 (75%) | |

| Metastatic nodes | |||

| No positive node | 76 (80.9%) | 18 (19.1%) | 9.54 (0.002) |

| 1 or more positive node(s) | 71 (61.2%) | 45 (38.8%) |

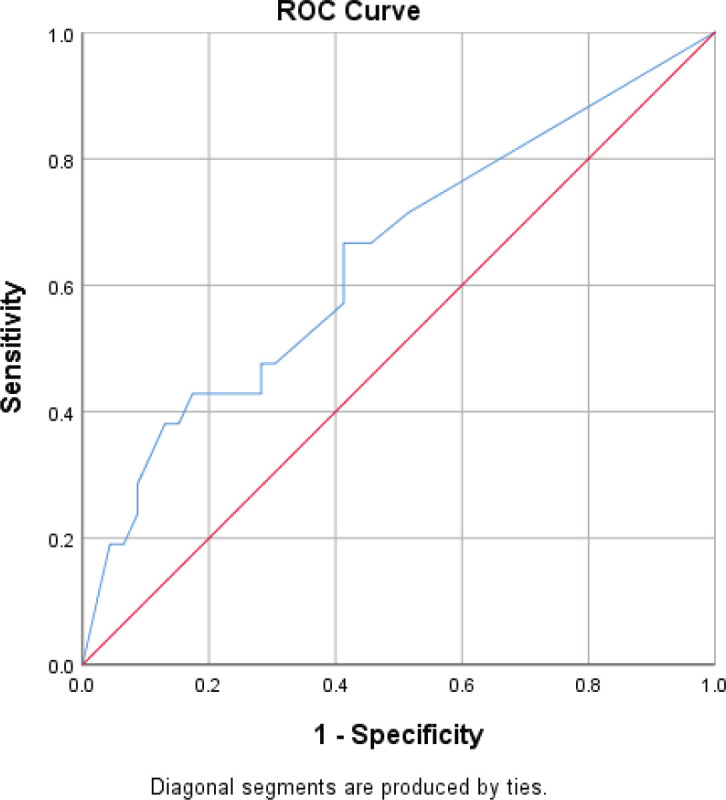

Table 4 shows adjusted and unadjusted hazard rates using the Cox regression model. Without adjusting for confounders, factors associated with survival were tumour size, tumour grade, resection margin, clinical evidence of locoregional recurrence, number of harvested nodes and metastatic nodes. Patients with an involved resection margin had 72% more hazard rate than those with free resection margin (HR = 1.72, p = 0.037) while those with a recurrent cancer had three times the hazard rate of those with no breast cancer recurrence (HR = 3.21, p < 0.001).

Table 4. Cox regression model showing adjusted and unadjusted hazard rates.

| Unadjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumour size (cm) | |||||

| ≤2 | 0.29 (0.09–0.92) | 0.036 | NA | ||

| 2.01–5 | 0.60 (0.29–1.24) | 0.170 | 1.06 (0.43–2.60) | 0.894 | |

| >5 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Tumour grade | |||||

| Low grade | 1 | 1 | |||

| Intermediate grade | 0.78 (0.44–1.39) | 0.401 | 0.39 (0.17–0.91) | 0.028 | |

| High grade | 0.21 (0.06–0.72) | 0.013 | 0.12 (0.03–0.45) | 0.002 | |

| Resection margin | |||||

| Free | 1 | ||||

| Involved | 1.72 (1.03–2.87) | 0.037 | 1.41 (0.70–2.84) | 0.334 | |

| Evidence of recurrence | |||||

| Yes | 3.21 (1.92–5.36) | <0.001 | 3.69 (1.51–9.02) | 0.004 | |

| No | 1 | ||||

| Harvested nodes | |||||

| 1–3 | 0.19 (0.06–0.63) | 0.006 | 0.43 (0.08–2.20) | 0.308 | |

| 4–9 | 0.40 (0.23–0.68) | 0.001 | 2.16 (0.87–5.39) | 0.098 | |

| ≥10 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Metastatic nodes | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1–3 | 0.61 (0.27–1.37) | 0.235 | 1.46 (0.49–4.37) | 0.496 | |

| 4–9 | 2.19 (1.18–4.04) | 0.013 | 3.61 (1.52–8.60) | 0.004 | |

| ≥10 | 31.62 (11.30–8.47) | < 0.001 | 48.25 (10.17–228.89) | <0.001 | |

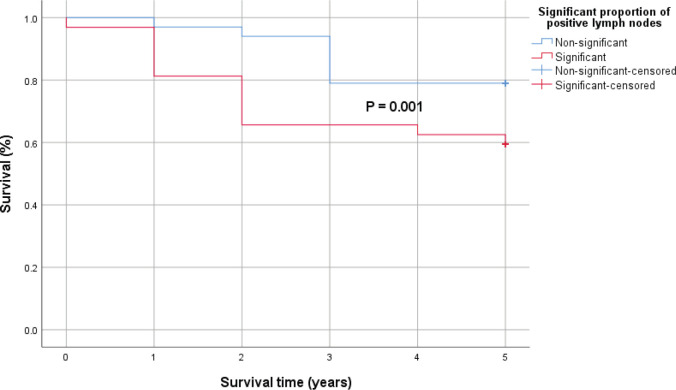

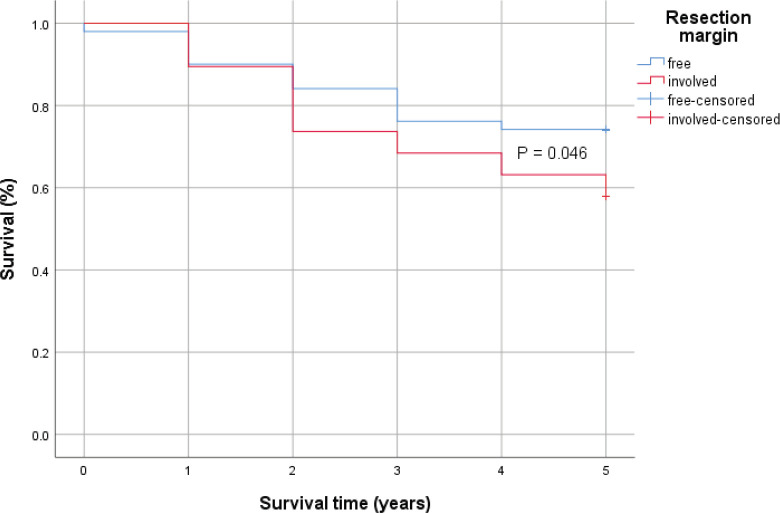

Patients with 1–3 metastatic nodes had 61% hazard rate from breast cancer (HR = 0.61, p = 0.235). This risk is 3.6 times higher in those with 4–9 metastatic nodes (HR = 2.19, p = 0.013), and 52 times higher in those with 10 or more metastatic nodes (HR = 31.62, p < 0.001). The above risk becomes higher when the hazard rate is adjusted. In patients who died, the proportion of metastatic lymph nodes was 33%, whereas 13% of metastatic lymph nodes were found in patients who survived (p = 0.001). With a sensitivity and specificity of 62% and 59% respectively, the cut-off proportion of metastatic lymph node that predicted mortality was 26% (Figure 1).

Figure 1. ROC curve for predicting survival using proportion of metastatic lymph nodes.

Patients with significantly higher proportion of positive lymph nodes (≥26%) recorded a statistically significant lower 5-year survival rates compared to those with lower positive lymph nodes (<26%). However, the difference in the 5-year survival outcomes with respect to positivity of resection margins was not statistically significant using the log-rank test (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing the 5-year survival of patients with significant proportion of positive lymph nodes (red) and those without (blue) with 0.001 p-value by log-rank test.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing the 5-year survival of patients with positive resection margin (Red) and those without (Blue) with 0.046 p-value by log-rank test.

Discussion

The clinico-epidemiologic characteristics of our cohort tallies with findings from other series in the sub-region in terms of mean age (46.8–49) [21–23], occupation [21, 23] and tumour sidedness. There is no specific pattern of predilection for tumour sidedness – 53.8% (121) of cancers involved the left breast as compared to a previous study from our division in which 52.2% of tumours were on the right [23]. The histologic type of 9 out of 10 breast cancer cases were invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC). Other investigators found similar figures: Kim et al [10] – 88.5% and Tonellotto et al [11] – 87%. However, the proportion of IDC obtained in a review carried out a decade earlier in the same centre was 70.3% [23]. About two-thirds (65.5%) of the tumours were either intermediate or high Scarff–Bloom–Richardson grade, consistent with regional epidemiology [22–24].This study highlights the molecular classification of breast carcinoma immunohistochemical subtypes into Lumina A (ER+/PR+), Lumina B (ER+/PR+/HER-2+), Basal-like (triple negative) and HER-2 enriched tumours, unlike most local studies in literature which provide hormone receptor stratification in isolated patterns, presenting an unorganised reference for comparison.

The overall median 5-year survival was 65.3%, as compared with 79% reported in some high-income countries (HIC) [25]. This disparity in survival outcome figures with HICs, despite our patients also receiving multimodal and integrated breast cancer care, could be as a result of a high proportion of premenopausal patients who present with advanced disease with unfavourable tumour grade and immunohistochemical pattern [14, 22]. Also, inability to complete standard adjuvant treatment regimen by some patients due to limited infrastructure and lack of funds [23] contributes to this outcome, as health care funding is mainly out of pocket. For example, the patients in our cohort do not routinely have granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) prophylaxis as per National Comprehensive Cancer Network protocol [26] but are given therapeutically and sometimes have to postpone some chemotherapy courses as a result of cost when they have haematologic chemotoxicity. Even after down staging with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and undergoing mastectomy, availability of external beam radiotherapy is limited in the country [27].

Resection margins were histologically free of cancer in almost three-quarters of the mastectomy specimens (72.4%). This is comparable to 73.5% found by Kim et al [10] Tumour involvement ranged from edges of excised specimen and axillary tail to underlying pectoral fascia. We did not perform a routine re-operation for microscopic residual cancer, rather adjuvant chemoradiation therapy was commonly utilised.

An average of 11 axillary nodes were harvested per patient, which is lower than 26 (range: 10–61) found in South Korean women [10], 19 (range: 6–77) documented by Tonellotto [11] and 15 (range: 2–31) reported by Abass et al [28] in Sudan, who also submitted that axillary lymph node dissection is considered efficacious if >10 nodes are harvested [29]. The lower yield in our series may be attributable to the fact that more than 50% of our patients had neoadjuvant chemotherapy which has been shown to reduce the number of lymph nodes retrieved in axillary dissection specimen [30]. The axillary dissection procedures were done by experienced breast surgeons and specimen grossing conducted by dedicated breast pathologists, which minimises the likelihood of inadequate clearance or retrieval. Based on the staging system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer and The Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) into pN1 (1‒3 positive lymph nodes), pN2 (4‒9 positive lymph nodes) and pN3 (≥10 positive lymph nodes), 47 patients were classified as pN1 (21%), 63 (28%) as pN2 and 12 (5.3%) as pN3 according to the number of positive lymph nodes.

While routine axillary node dissection is not recommended in phyllodes tumour as nodal involvement is rare [31], many authors support nodal clearance in cases of palpable axillary nodes [32, 33], even though only 1.1%–3.8% of clinically evident nodes have been reported to be pathologically positive [31]. Palpable nodes in three patients with phyllodes tumour in our series necessitated clearance.

Tumour size, tumour grade, resection margin, evidence of recurrence, harvested nodes and metastatic nodes were associated with survival. Hazard rates in the Cox regression analysis, however, showed that after adjusting for confounders, patients with cancer recurrence were about four times less likely to survive till the end of the follow up period (95% CI, 1.92–5.36; p < 0.001).

The trade-off plot of the ROC curve present classifiers with a sensitivity and specificity of 62% and 59%, respectively, the cut-off proportion of histologically positive lymph node predicting disease-specific 5-year mortality being 26%.

In cases with significantly higher proportion of malignant lymph nodes (≥26%), there was a statistically significantly lower 5-year survival rates compared to those with lower positive lymph nodes (<26%). Even though patients with microscopic residual tumour in resection margins had 72% more hazard rate than those with negative resection margin (HR = 1.72, p = 0.037) in a time-to-event analysis, the difference in the 5-year survival outcomes with respect to positivity of resection margins was not statistically significant using the log-rank test (p= 0.046).

Conclusion

The clinico-epidemiology characteristics of our patients are similar to that seen worldwide; a high positive lymph node ratio is associated with poorer survival rates. Tumour recurrence is also associated with poor survival and is seen commonly with positive resection margins. However, the 5-year survival outcome was unfavourable. This is attributed to limited infrastructure, e.g., radiotherapy service, lack of funds and late clinico-pathologic presentation by patients.

Limitations

Challenges in delivery of complete multimodal treatment regimen to our patients, including unbearable costs, suboptimal access to radiation therapy and poor uptake of immunotherapy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(8):394–4242.. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization International Agency for Research on Cancer. Latest global cancer data: Cancer burden rises to 18.1 million new cases and 9.6 million cancer deaths in 2018. Geneva: GLOBOCAN; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jedy-Agba E, Curado MP, Ogunbiyi O, et al. Cancer incidence in Nigeria: a report from a population-based cancer registry. Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;36(5):271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adisa CA, Eleweke N, Alfred AA, et al. Biology of breast cancer in Nigerian women: a pilot study. Ann Afr Med. 2012;11(3):169–175. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.96880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fregene A, Newman LA. Breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: How does it relate to breast cancer in African‑American women? Cancer. 2005;103(8):1540–1550. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amin SM, Ewunonu HAS, Oguntebi E, et al. Breast cancer mortality in a resource‑poor country: a 10-year experience in a tertiary institution. Sahel Med J. 2017;20(3):93–97. doi: 10.4103/smj.smj_64_15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pruitt L, Mumuni T, Raikhel E, et al. Social barriers to diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer in patients presenting at a teaching hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria. Glob Public Health. 2015;10(3):331–344. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.974649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anyanwu SNC, Egwuonwu OA, Ihekwoaba EC. Acceptance and adherence to treatment among breast cancer patients in Eastern Nigeria. Breast. 2011;20(Suppl. 2):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saadatmand S, Bretveld R, Siesling S, et al. Influence of tumour stage at breast cancer detection on survival in modern times: population based study in 173797 patients. BMJ. 2015;351:h4901. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim S, Choi DH, Huh SJ, et al. Lymph node ratio as a risk factor for loco-regional recurrence in breast cancer patients with 10 or more axillary nodes. J Breast Cancer. 2016;19(2):169–175. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.2.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tonellotto F, Bergmann A, de Souza Abrahão K, et al. Impact of number of positive lymph nodes and lymph node ratio on survival of women with node-positive breast cancer. Eur J Breast Health. 2019;15(2):76–84. doi: 10.5152/ejbh.2019.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Woodward WA, Vinh-Hung V, Ueno NT, et al. Prognostic value of nodal ratios in node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(18):2910–2916. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vinh-Hung V, Verkooijen HM, Fioretta G, et al. Lymph node ratio as an alternative to pN staging in node-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1062–1068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanderpuye V, Grover S, Hammad N, et al. An update on the management of breast cancer in Africa. Infect Agent Cancer. 2017;12:13. doi: 10.1186/s13027-017-0124-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heil J, Fuchs V, Golatta M, et al. Extent of primary breast cancer surgery: standards and individualized concepts. Breast Care. 2012;7(5):364–369. doi: 10.1159/000343976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orosco RK, Tapia VJ, Califano JA, et al. Positive surgical margins in the 10 most common solid cancers. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):5686. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23403-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meric F, Mkirza NQ, Vlastos G, et al. Positive Surgical Margins and Ipsilateral Breast tumor recurrence predict disease-specific survival after breast-conserving therapy. Cancer. 2003;97(4):926–933. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ngowa JDK, Kasia JM, Yomi J, et al. Breast cancer survival in cameroon: analysis of a cohort of 404 patients at the Yaoundé General Hospital. Adv Breast Cancer Res. 2015;4(2):44–52. doi: 10.4236/abcr.2015.42005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKenzie F, Zietsman A, Galukande M, et al. African Breast Cancer—Disparities in Outcomes (ABC-DO): protocol of a multicountry mobile health prospective study of breast cancer survival in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Open. 2016;6(8):e011390. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Said AA, Abd-Elmegid LA, Kholeif S, et al. Stage-specific predictive models for main prognosis measures of breast cancer. Future Comput Informat J. 2018;3(2):391–397. doi: 10.1016/j.fcij.2018.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huo D, Adebamowo CA, Ogundiran TO, et al. Parity and breastfeeding are protective against breast cancer in Nigerian women. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(5):992–996. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adesunkanmi ARK, Lawal OO, Adelusola KA, et al. The severity, outcome and challenges of breast cancer in Nigeria. Breast. 2006;15(3):399–409. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogundiran TO, Ayandipo OO, Ademola AF, et al. Mastectomy for management of breast cancer in Ibadan, Nigeria. BMC Surg. 2013;13:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adebamowo CA, Famooto A, Ogundiran TO, et al. Immunohistochemical and molecular subtypes of breast cancer in Nigeria. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110(1):183–188. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9694-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sankaranarayanan R, Swaminathan R, Brenner H, et al. Cancer survival in Africa, Asia, and Central America: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(2):165–173. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helwick C, Goodman A, Barbor M. Breast Cancer NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. 2019. The ASCO Post. 2019 May, Version 3.

- 27.Anderson U. Assessment of radiotherapy center availability in Nigeria and utilization review in selected tertiary hospitals in south-east and south-west geopolitical zones [Project] 2018. Afrilibrary.

- 28.Abass MO, Gismalla MDA, Alsheikh AA, et al. Axillary lymph node dissection for breast cancer: efficacy and complication in developing countries. J Glob Oncol. 2018;4:1–8. doi: 10.1200/JGO.18.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Axelsson CK, Mouridsen HT, Zedeler K. Axillary dissection of level I and II lymph nodes is important in breast cancer classification. Eur J Cancer. 1992;28:1415–1418. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90534-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belanger J. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in invasive breast cancer results in a lower axillary lymph node count. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(4):704–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shafi AA, AlHarthi B, Riaz MM, et al. Giant phyllodes tumour with axillary and interpectoral lymph node metastasis; a rare presentation. Int J Surg. 2020;66:350–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reinfuss M, Mitus J, Duda K, et al. The treatment and prognosis of patients with phyllodes tumour of the breast: an analysis of 170 cases. Cancer. 1996;77:910–916. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960301)77:5<910::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ward RM, Evans HL. Cystosarcoma phyllodes: a clinicopathologic study of 26 cases. Cancer. 1986;58:2282–2289. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19861115)58:10<2282::AID-CNCR2820581021>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]