Abstract

Background

Psoriasis, a chronic immune-mediated disease, is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality. Secukinumab selectively neutralizes IL-17A and has demonstrated high efficacy with a favorable safety profile in various psoriatic disease manifestations.

Trial Design and Methods

Subsequent to the 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind treatment period, moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients received secukinumab for 40 weeks. Vascular inflammation using FDG-PET/CT imaging and blood-based cardiometabolic was assessed at week 0, 12, and 52.

Results

The difference in change in aortic inflammation from baseline to Week 12 for secukinumab (N=46) versus placebo (N=45) was −0.053 (95% CI: −0.169, 0.064; P=0.37). Small increases in total cholesterol, LDL, and LDL particles, but no changes in markers of inflammation, adiposity, insulin resistance, or predictors of diabetes, were observed with secukinumab treatment compared with placebo. At Week 52, reductions in TNF-α (P=0.0063) and ferritin (P=0.0354), and an increase in fetuin A (P=0.0024), were observed with secukinumab treatment compared to baseline. No significant changes in aortic inflammation or markers of advanced lipoprotein characterization, adiposity, or insulin resistance were observed with secukinumab treatment compared to baseline.

Conclusion

Secukinumab exhibited a neutral impact on aortic vascular inflammation and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease after 52 weeks of treatment.

Keywords: Secukinumab, cardiovascular, vascular inflammation, psoriasis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease affecting over 125 million people worldwide (Kurd and Gelfand, 2009, Parisi et al., 2013). The inflammatory pathways that are upregulated in psoriasis are also important factors in the development of cardiometabolic diseases (Hawkes et al., 2017, Nestle et al., 2009), including dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and mortality (Gelfand et al., 2006, Gelfand et al., 2007, Noe et al., 2018, Wan et al., 2018). Recognizing the clinical importance of cardiovascular risk in inflammatory diseases, recent cardiovascular guidelines now define psoriasis as a risk-enhancing condition warranting early initiation of therapy (e.g., statins) (Elmets et al., 2019, Grundy et al., 2018). Moreover, the presence of cardiovascular risk factors and disease is often an important factor when selecting psoriasis treatment (Kaushik and Lebwohl, 2019). The biologic mechanisms linking psoriasis to adverse cardiometabolic outcomes are complex and incompletely understood, given the multiple pathways involved in atherosclerotic disease-related cardiovascular events (Sajja et al., 2018). In recent years, psoriasis has been increasingly recognized as a disease driven by interleukin (IL)-23/IL-17 based on response to treatments targeting these cytokines, including interleukin-17A (IL) (Menter et al., 2019), the IL-17 receptor (Lebwohl et al., 2015, Menteret al., 2019, Papp et al., 2012), and IL-23 (Blauvelt et al., 2017, Reich K et al., 2019). The role that IL-17 plays in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is controversial (Ait-Oufella et al., 2019). Mouse models suggest both pro- and anti-atherosclerotic effects of IL-17. In the Apoe−/− mouse model, administration of IL-17A neutralizing antibodies resulted in attenuation of aortic root lesions (Erbel C. et al., 2009), whereas opposite effects were observed in Ldlr−/− mice (Danzaki et al., 2012, Erbel Christian et al., 2009, Ge et al., 2013, Smith et al., 2010, van Es et al., 2009). In humans, higher IL-17 expression has been associated with stability of advanced carotid artery plaques (Gisterå et al., 2013). Furthermore, in patients with acute coronary syndrome, those with higher IL-17 levels at the time of event had a lower risk of future CV events (Simon et al., 2012), suggesting that IL-17 may modulate tissue responses to myocardial injury. A recent pilot study demonstrated that treatment with IL-17A inhibitors was associated with a reduction in coronary plaque after one year of treatment. However, this was an open-label, observational study (Elnabawi et al., 2019). Initial studies of IL-17A inhibitors in patients with psoriasis have shown no impact (with large confidence intervals [CIs]) on MACE (OR 1·00, 95% CI 0·09–11·09) during the placebo-controlled portion of clinical studies (Strober et al., 2017). However, much larger and longer-term studies in humans will be necessary to determine the true impact of IL-17 inhibition on CVD (Gelfand, 2018, Rungapiromnan et al., 2017). Thus, how inhibition of IL-17 modulates cardiovascular risk in humans with psoriasis also remains uncertain.

In contrast to IL-17 and its isoforms, the role of other pro-inflammatory cytokines in accelerating CVD is more defined. For example, IL-1 and IL-6 have been causally linked to CVD through clinical studies and Mendelian randomization studies, respectively (Consortium, 2012, Ridker et al., 2017). Of note, IL-6 can promote differentiation of naive CD4+ T lymphocytes into Th17 cells, demonstrating the complex interplay between inflammatory pathways in the skin and blood (Stockinger and Omenetti, 2017).

To better dissect the impact of anti-cytokine treatments on cardiometabolic disease in humans, we have conducted a series of randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled studies in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis to determine the impact of biologics on subclinical vascular disease. These studies assessed vascular inflammation by fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT) (Dey et al., 2017, Hjuler et al., 2017, Kaur et al., 2018, Mehta et al., 2011a) as a marker of sub-clinical vascular disease, which although not a direct marker of coronary heart disease, is known to be predictive of future major cardiovascular events and improves rapidly (i.e., within 4-12 weeks) with treatments (i.e., statins) proven to prevent cardiovascular disease and therefore is a well accepted surrogate marker for early trials of novel therapies for cardiovascular diseases (Figueroa et al., 2013, Lee et al., 2008, Mehta et al., 2012, Tahara et al., 2006, Tawakol et al., 2013). Simultaneously, we measured blood markers of inflammation, lipids, and glucose metabolism. In the first Vascular Inflammation in Psoriasis (VIP) study, blockade of TNF-α (tumor necrosis factor) with adalimumab had a neutral impact on aortic vascular inflammation, lipids, and glucose metabolism, and a beneficial effect on markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), TNF-α, IL-6, and Glycoprotein acetyls (GlycA) compared to placebo (Mehta et al., 2018). In this trial, narrow band ultraviolet B phototherapy was used as a non-systemic treatment control, which demonstrated a neutral impact on aortic vascular inflammation and glucose metabolism, decreased levels of CRP and IL-6, and an increase in high-density lipoprotein-p. Compared to placebo in the VIP-Ustekinumab study, blockade of IL-12/IL-23 for 12 weeks resulted in reductions in aortic vascular inflammation and serum vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), with no effects on CRP, TNF-α, IL-6, GlycA, and glucose metabolism. There was also a slight increase in cholesterol levels, possibly due to an increase in apolipoprotein-B lipoproteins (Gelfand et al., 2019). Here, in a prospective randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study, we determined the effect of secukinumab, an antibody selectively targeting IL-17A, on aortic vascular inflammation and blood-based markers of inflammation, lipids, and glucose metabolism compared to placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.

Results

One hundred thirty-nine patients were screened and 91 were randomized, 46 to secukinumab and 45 to placebo (Supplementary Figure S1). Forty-four patients randomized to secukinumab completed the study through Week 12 (2 [4.3%] patients discontinued due to adverse events), and 42 initially assigned to placebo completed up to Week 12 (3 [6.7%] patients discontinued, 2 for AEs and 1 for patient/guardian decision). Eighty-six patients entered the double-blinded treatment phase (second phase) of the study, of whom 78 completed the study (8 [8.8%] patients discontinued, 2 for AEs, 1 for lack of efficacy, 2 lost to follow-up, 1 for protocol deviation, and 2 for patient/guardian decision). Patients average age was 47 years (SD 13.7), 67% were male, and 79% were Caucasian; average body mass index (BMI) was 32, mean body surface area (BSA) was 29%, and the mean Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) was of 22 (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were similar between the two treatment groups, but those assigned to placebo were numerically more likely to have a prior diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis and a prior diagnosis of conditions related to CVD (Table 1).

Table 1:

Demographics and background characteristics (Randomized Set)

| Secukinumab n=46 |

Placebo n=45 |

Total N=91 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean years (SD) | 47.9 (12.7) | 47.0 (14.7) | 47.4 (13.7) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Female | 13 (28.3) | 17 (37.8) | 30 (33.0) |

| Male | 33 (71.7) | 28 (62.2) | 61 (67.0) |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 36 (78.3) | 36 (80.0) | 72 (79.1) |

| Black | 1 (2.2) | 3 (6.7) | 4 (4.4) |

| Asian | 6 (13.0) | 2 (4.4) | 8 (8.8) |

| Other | 3 (6.5) | 4 (8.9) | 7 (7.7) |

| Ethnicity n (%) | |||

| Hispanic | 15 (32.6) | 15 (33.3) | 30 (33.0) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 31 (67.4) | 30 (66.7) | 61 (67.0) |

| Unknown/missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 31.09 (6.8) | 32.75 (7.8) | 31.91 (7.3) |

| Medical history n (%) | |||

| Coronary artery Disease |

1 ( 2.2) | 4 ( 8.9) | 5 ( 5.5) |

| Depression | 3 (6.5) | 7 (15.6) | 10 (11.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0 (0.0) | 5 (11.1) | 5 (5.5) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8 (17.4) | 11 (24.4) | 19 (20.9) |

| Hypertension | 11 (23.9) | 16 (35.6) | 27 (29.7) |

| Stroke | (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Statin use | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) |

| Baseline total % BSA | |||

| Mean (SD) | 27.6 (19.3) | 30.1 (18.7) | 28.8 (19.0) |

| Median (p25, p75) | 21.5 (13.9, 36.0) | 21.4 (18.0, 40.6) | 21.4 (15.0, 37.4) |

| Baseline PASI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.5 (12.0) | 21.4 (9.9) | 22.0 (11.0) |

| Median (p25, p75) | 17.9 (14.2, 26.7) | 18.6 (14.9, 22.8) | 18.0 (14.7, 24.4) |

| Baseline IGA mod 2011 n (%) | |||

| 3=Moderate disease | 31 ( 67.4) | 28 ( 62.2) | 59 ( 64.8) |

| 4=Severe disease | 15 ( 32.6) | 17 ( 37.8) | 32 ( 35.2) |

| Psoriasis duration (years) | |||

| N | 45 | 45 | 90 |

| Mean (SD) | 16.3 (12.3) | 15.4 (12.5) | 15.9 (12.4) |

| Median (p25, p75) | 14.0 (5.0, 25.0) | 14.0 (6.0, 20.0) | 14.0 (5.0, 24.0) |

| Treatment history, n (%) | |||

| Biologics | 20 (43.5) | 16 (35.6) | 36 (39.6) |

| Non-biological systemic therapy | 13 ( 28.3) | 14 ( 31.1) | 27 ( 29.7) |

| Phototherapy | 14 (30.4) | 13 (28.9) | 27 (29.7) |

| PsA present (%) | |||

| Yes | 6 (13.0) | 11 (24.4) | 17 (18.7) |

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; N, total number of patients; n, number of patients; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis; SD, standard deviation;

TBR, target-to-blood pool ratio; p25, 25th percentile; p75, 75th percentile

As anticipated, secukinumab was highly efficacious in treating psoriasis (Table 2). At Week 12, secukinumab-treated patients had 74% and 78% greater differences in achieving PASI 90 and Investigator’s Global Assessment modified 2011 (IGA mod 2011) 0 or 1 responses, respectively, compared to placebo (P<0.0001 for all). At Week 52, PASI 90 and IGA mod 2011 0 or 1 response rates were 53% and 57%, respectively.

Table 2:

Physician-reported psoriasis variables: Weeks 12 and 52

| Variables n (%) |

Week 12* | Difference in percentage | Week 52† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secukinumab n=46 |

Placebo n=45 |

Estimated value |

95% CI | P value | Secukinumab n=78 |

|

| PASI 90 | 34 (74) | 0 | 73.9 | (61.22, 86.60) | <0.0001 | 53 (68) |

| IGA mod 2011 0/1 (clear/almost clear) | 36 (78.3) | 0 | 78.3 | (66.34, 90.18) | <0.0001 | 57 (73) |

Non-responder imputation

Observed cases

P values at Week 12 are for comparison of secukinumab with placebo

IGA, Investigator's Global Assessment; n, number of patients; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

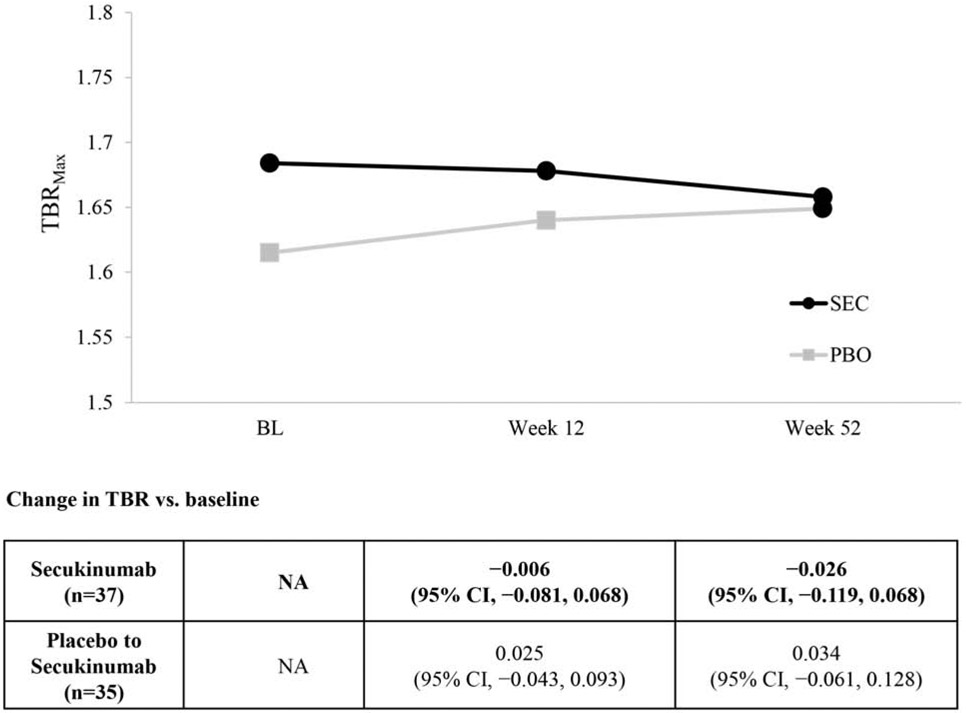

Patients assigned to secukinumab had a 2.6% (95% CI: −2.5%, 7.6%) increase in target-to-blood pool ratio (TBR) at Week 12 compared to baseline, while patients assigned to placebo had a 3.3% (95% CI: −0.8%, 7.5%) increase during the same time period; however, neither of these numbers nor the differences were statistically significant (Table 3). The difference in least squares means (LSM) change in TBR from baseline to Week 12 of secukinumab compared to placebo was −0.053 (95% CI: −0.169, 0.064; P=0.37) (primary efficacy variable). An analysis based on percent change found that patients treated with secukinumab experienced a non-statistically significant −0.75% reduction (95% CI: −7.2%, −5.7%) in TBR at Week 12 compared with percentage changes in the placebo group. At Week 52, there was no statistically significant change in TBR compared to baseline for those initially assigned to secukinumab (N=37, −2.6%, 95% CI: −11.9%, 6.8%) and those initially assigned to placebo who then started secukinumab at Week 12 (N=35, 3.4%, 95% CI: −6.1%, 12.8%) (Figure 1). A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted in patients with a TBR >1.6 at baseline (a previously utilized entry criteria for a cardiovascular drug development trial (Fayad et al., 2011)). Within-group changes demonstrated a −0.11 (95% CI: −0.20, −0.02) reduction in aortic vascular inflammation (P=0.02) at Week 12 compared to baseline for those initially assigned secukinumab; however, those initially assigned to placebo and then crossed over to secukinumab at week 12 experienced a non-statistically significant within group TBR increase of +0.11 (95% CI, −0.02, 0.24) at Week 52 compared to Week 12) (Supplementary Table S1a). No other statistically significant changes were observed at other time points for those initially assigned secukinumab or for those individuals who initially received placebo followed by secukinumab from Week 12 to Week 52. Additional post hoc sensitivity analyses evaluating different subgroups based on PASI responses, BMI, age, and cardiovascular risk status are shown in Supplementary Table S1b, and did not change the primary results.

Table 3:

18-FDG PET/CT primary assessment: Total aortic vascular inflammation at Week 12

| Variables | Secukinumab n=43 |

Placebo n=42 |

Difference (Secukinumab – Placebo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline (primary efficacy variable), LSM | 0.017 | 0.070 | −0.053 (95% CI, −0.169, 0.064); P=0.37 |

| % change from baseline, mean | 2.6% (95% CI, −2.5%, 7.6%); P=0.31 | 3.3% (95% CI, −0.8%, 7.5%); P=0.12 | −0.75% (95% CI, −7.2%, 5.7%); P=0.82 |

18-FDG PET/CT, 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography with computer assisted tomography scans; CI, confidence interval; LSM, least squares mean; n, number of patients; TBR, target-to-blood pool ratio

Figure 1: Whole aorta TBRmax in Week 52 completers.

BL, baseline; CI, confidence interval; n, number of patients; TBR, target-to-blood pool ratio

Changes in blood biomarkers of advanced lipoprotein characterization, inflammation, adiposity, insulin resistance, and predictors of diabetes are shown in Tables 4 and 5. At Week 12, patients randomized to secukinumab had a small, but statistically significant increase in total cholesterol, LDL, and LDL particles compared to placebo with no statistically significant changes in biomarkers of inflammation, adiposity, insulin resistance, and predictors of diabetes (Table 4). At Week 52, there were no statistically significant changes in markers of advanced lipoprotein characterization compared with baseline, and no statistically significant changes in markers of adiposity or insulin resistance. There were statistically significant reductions in TNF-α (P=0.0063) and ferritin (P=0.0354), and an increase in fetuin A at Week 52 (P=0.0024) (Table 5).

Table 4:

Effect of secukinumab on cardiometabolic biomarkers: Changes from baseline at Week 12

| Variable, LSM | SEC 300 mg n=46 |

Placebo n=45 |

LSM Difference (Secukinumab – Placebo) |

95% CI for treatment difference |

P- valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced lipoprotein characterization | |||||

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 10.8 | −8.4 | 19.2 | (6.2, 32.2) | 0.0043 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.8 | −1.6 | 0.8 | (−2.6, 4.2) | 0.6367 |

| HDL function (cholesterol efflux) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.05 | (−0.05, 0.1) | 0.3086 |

| HDL particle total (μmol/L) | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 | (−1.8, 2.2) | 0.8651 |

| HDL Size (nm) | 0.042 | −0.002 | 0.05 | (−0.1, 0.2) | 0.5904 |

| IDL particle total (nmol/L) | 52.4 | 6.2 | 46.2 | (−12.1, 104.4) | 0.1188 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 10.5 | −5.8 | 16.3 | (3.4, 29.2) | 0.0137 |

| LDL particle total (nmol/L) | 112.0 | −94.8 | 206.7 | (77.9, 335.6) | 0.0020 |

| LDL size (nm) | 0.01 | 0.1 | −0.1 | (−0.3, 0.2) | 0.4464 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 11.2 | −9.2 | 20.4 | (−2.0, 42.8) | 0.0741 |

| VLDL particle total (nmol/L) | 2.8 | 3.5 | −0.7 | (−11.0, 9.6) | 0.8917 |

| VLDL size (nm) | 0.1 | −1.1 | 1.2 | (−1.6, 4.0) | 0.3919 |

| Inflammation | |||||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | −0.5 | −0.8 | 0.3 | (−0.2, 0.7) | 0.2577 |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/mL) | 2.0 | −2.1 | 4.1 | (−2.7, 10.9) | 0.2331 |

| CRP (mg/L) | −1.6 | 1.5 | −3.1 | (−8.3, 2.1) | 0.2413 |

| GlycA | −3.7 | 2.9 | −6.6 | (−28.0, 14.8) | 0.5410 |

| Adiposity | |||||

| Leptin (pg/mL) | −3741.1 | −3097.8 | −643.3 | (−4801.1, 3514.6) | 0.7590 |

| Adiponectin total (ng/mL) | 1424.9 | −1080.3 | 2505.2 | (−3359.5, 8369.9) | 0.3979 |

| Insulin resistance | |||||

| HOMA-IR | 0.5 | −0.7 | 1.2 | (−0.2, 2.6) | 0.0878 |

| Predictive of diabetes | |||||

| Apolipoprotein B (ng/mL) | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.001 | (−0.02, 0.02) | 0.9347 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | −7.2 | −14.8 | 7.5 | (−15.9, 30.9) | 0.5248 |

| IL-2 receptor A (pg/mL) | −3.1 | −2.1 | −1.0 | (−11.9, 9.9) | 0.8608 |

| IL-18 (pg/mL) | 32925.3 | −3763.0 | 36688.3 | (−34807, 108183) | 0.3103 |

| Fetuin A (ng/mL) | 56948.5 | 79453.7 | −22505 | (−205030, 160020) | 0.8068 |

P-values calculated by ANCOVA

ANOVA, analysis of variance; CRP, C-reactive protein; GlycA, Glycoprotein acetyls; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein; IL, interleukin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LDL-P, low-density lipoprotein particle; LSM, least squares mean; SEC, secukinumab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

Table 5:

Effect of secukinumab on cardiometabolic biomarkers: Changes from baseline at Week 52

| Variable, LSM | Secukinumab N=91 |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced lipoprotein characterization | ||

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.1 | 0.7380 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | −0.6 | 0.5219 |

| HDL function (cholesterol efflux) | 0.04 | 0.2213 |

| HDL particle total (μmol/L) | −0.2 | 0.7446 |

| HDL Size (nm) | 0.06 | 0.3128 |

| IDL particle total (nmol/L) | 22.7 | 0.1978 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1.4 | 0.6567 |

| LDL particle total (nmol/L) | −11.3 | 0.7726 |

| LDL size (nm) | 0.07 | 0.3981 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 5.9 | 0.4121 |

| VLDL particle total (nmol/L) | 0.007 | 0.9983 |

| VLDL size (nm) | 1.3 | 0.2176 |

| Inflammation | ||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | −0.9 | 0.0063 |

| Interleukin 6 (pg/mL) | −2.4 | 0.1606 |

| CRP (mg/L) | −1.6 | 0.0664 |

| GlycA | −4.0 | 0.4512 |

| Adiposity | ||

| Leptin (pg/mL) | −1854.4 | 0.2522 |

| Adiponectin total (ng/mL) | −1802.7 | 0.2582 |

| Insulin resistance | ||

| HOMA-IR | −0.2 | 0.6186 |

| Predictive of diabetes | ||

| Apolipoprotein B (ng/mL) | 0.01 | 0.1264 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | −16.6 | 0.0354 |

| IL-2 receptor A (pg/mL) | 0.002 | 0.9996 |

| IL-18 (pg/mL) | −47.5 | 0.4239 |

| Fetuin A (ng/mL) | 142675.3 | 0.0024 |

p-values calculated by linear regression

CRP, C-reactive protein; GlycA, Glycoprotein acetyls; HOMA-IR, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IDL, intermediate-density lipoprotein; IL, interleukin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LDL-P, low-density lipoprotein particle; LSM, least squares mean; N, total number of patients; SEC, secukinumab; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VLDL, very low-density lipoprotein.

Safety data are presented in Supplementary Table S2, with a listing of non-serious AEs that occurred in more than 5% of patients in any randomized arm. During the randomized double-blinded treatment period, there were 26 (56.5%) AEs in those treated with secukinumab (2 [4.3%] of which were serious) and 16 (35.6%) AEs in those treated with placebo (none of which were serious). The two serious adverse events in the first treatment period occurred in 2 patients and were rib fracture and upper limb fracture. Over the entire treatment period (52 weeks), when all patients received secukinumab, there were 37 (80.4%) AEs, of which 5 (10.9%) were serious. The serious adverse events over the 52 weeks occurred in 5 patients and included abdominal pain, rib fracture, upper limb fracture, muscular weakness, and aortic stenosis.

Discussion

We conducted a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study to determine the impact of secukinumab, an anti-IL-17A antibody, on important markers of vascular disease risk compared with placebo in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. As anticipated, secukinumab resulted in excellent reduction in the signs and symptoms of psoriasis. At Week 12, there was no change in aortic inflammation, i.e., TBR, in secukinumab-treated patients compared to placebo. Based on the 95% CI of this observation (95% CI: −7.2%, 5.7%), it is likely that short-term exposure to secukinumab has no clinically significant impact on aortic vascular inflammation as assessed by FDG-PET/CT (Gelfand J. M. et al., 2019, Mehta et al., 2018). Moreover, longer-term exposure to secukinumab (52 weeks for those originally assigned to secukinumab or 40 weeks for those initially assigned placebo) also showed no discernible effects on aortic vascular inflammation, reinforcing the primary outcome finding. The results were robust in a number of sensitivity analyses. Patients who had higher aortic vascular inflammation at baseline and received secukinumab showed evidence of TBR improvement at Week 12. This finding, however, was not replicated when patients initially assigned to placebo were crossed over to secukinumab. Other trials evaluating the impact of biologics on vascular inflammation in psoriasis have required patients to have higher vascular inflammation by entry TBR value >1.6 (Bissonnette et al., 2017); however, this approach limits the generalizability of the results, may mask paradoxical effects of targeted biologic treatment on inflammation, and as previously demonstrated, is not necessary to demonstrate a reduction in aortic vascular inflammation in psoriasis patients treated with a biologic (i.e., ustekinumab) compared to placeo (Gelfand J. M. et al., 2019). Results in this study are largely similar to a recently published trial, which found that secukinumab had minimal effect on flow-mediated dilatation (a marker of early vascular disease, e.g., endothelial dysfunction) compared to placebo (von Stebut et al., 2019). The results are in contrast to a study that demonstrated an improvement in left ventricle global longitudinal strain, left ventricle twisting, and untwisting, coronary flow reserve and pulse wave velocity in patients treated with secukinumab compared to methotrexate or cyclosporine; however, this study was not placebo controlled and did not evaluate extensive cardiovascular biomarkers of inflammation, lipid, and glucose metabolism (Makavos et al., 2019).

We also evaluated the effect of secukinumab on markers of inflammation, lipoproteins, adiposity, and insulin resistance, which are dysregulated in patients with psoriasis, and associated with adverse atherosclerotic outcomes and/or incident diabetes mellitus (Sajja et al., 2018). After 12 weeks of therapy, patients treated with secukinumab had a small increase in total cholesterol driven by increases in LDL and LDL particles, but these changes were transient and not sustained at 52 weeks. Additionally, there were no differences in markers of inflammation, adiposity, insulin resistance, or predictors of diabetes at 12 weeks between the secukinumab and placebo groups. At 52 weeks, there were reductions in TNF-α and ferritin, and an increase in fetuin A. Thus, despite rapid and sustained improvement in psoriasis observed with secukinumab treatment, there were no impacts on aortic vascular inflammation and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease.

Strengths of our study include its rigorous placebo-controlled design, plus the comprehensive evaluation of imaging and serum biomarkers of inflammation, lipids, and glucose metabolism. Limitations include a relatively small sample size, which limited our ability to fully investigate a post hoc analysis such as evaluating the effect of secukinumab in patients with higher levels of aortic vascular inflammation at baseline and which possibly resulted in insufficient statistical power for some biomarkers. For example, pooled results from larger studies have shown statistically significant improvements in hsCRP in moderate-to-severe psoriasis patients with comorbid psoriatic arthritis treated with secukinumab compared to placebo (Gottlieb AB, 2015). We also evaluated a number of biomarkers, which can lead to type-1 errors. Furthermore, other pathways that may be important links between psoriasis and cardiovascular events, including platelet function and immune-cell populations by flow cytometry, were not evaluated (Takeshita et al., 2014). Additionally, the cardiovascular markers tested here have primarily been evaluated in older patients, often with established cardiovascular disease or restricted to those with higher levels of a CV biomarker of interest at baseline. Thus, additional studies may be warranted in higher risk and more CV disease-enriched populations. Finally, our primary outcome, aortic vascular inflammation, may not fully capture impacts on vascular beds of coronary arteries, the primary sites involved in myocardial infarction. To this point, in a small pilot study in psoriasis we recently demonstrated that one year of treatment with anti-IL-17A therapy was associated with a reduction in total coronary plaque burden, with no worsening of atherosclerotic plaque features, compared to patients with psoriasis not treated with biologic therapy (Elnabawi et al., 2019). Therefore, it is possible that measuring FDG uptake in the aorta is not as sensitive as coronary artery plaque characterization by coronary CT with angiography, when studying possible CV changes associated with anti-inflammatory treatment. Additionally, it is possible that reduction of bioavailable IL-17A modulates immune cells associated more with early coronary artery plaque formation than cells associated with early aortic inflammation. Multimodal imaging studies performed simultaneously are needed to better address this issue.

In summary, treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis with secukinumab resulted in rapid and sustained improvement in psoriasis, but had a neutral impact on aortic vascular inflammation and biomarkers of cardiometabolic disease. Additional studies evaluating the effects of IL-17A inhibition in patients with higher CV risk that incorporate direct measures of coronary artery disease and MACE events are necessary to more fully understand the CV effects of IL-17A in humans.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter study in adult patients (≥18 years of age) with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis (Supplementary Figure S2). Twelve investigative sites in the United States participated between Feb 10, 2016, and Feb 19, 2018 (NCT02690701; clinicaltrials.gov) and consisted of a screening period (≤4 weeks), a double-blinded treatment period (12 weeks), followed by a double-blinded induction period (4 weeks), and an open-label treatment period (36 weeks). At the beginning of the double-blinded treatment period, eligible patients were randomized (1:1) to either secukinumab 300 mg or placebo. Patients on secukinumab 300 mg who completed the double-blinded treatment phase were sham-induced to placebo injections at Weeks 13, 14, and 15, while patients who were on placebo were switched to secukinumab at Week 12 and received the loading dose of active drug at Weeks 13, 14, 15, and 16. At the end of the double-blinded induction period, all patients were switched to open-label secukinumab 300 mg for the remainder of the study.

Protocol

Three protocol amendments were carried out (after 5, 26, and 107 weeks) after the initiation of the study. Of the amendments carried out, the notable ones were the inclusion of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥7% as an exclusionary laboratory value, and revision of the list of cardiometabolic biomarkers under investigation in the study.

Participants

Adult patients diagnosed with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis (≥6 months prior to randomization), with ≥10% BSA involvement, PASI ≥12, and IGA mod 2011 score ≥3 (based on a scale of 0 to 4) at baseline, and who were eligible for systemic therapy were included in the study. Patients underwent clinical examinations (including FDG-PET/CT), and their results were required to not meaningfully alter the risk-benefit profile of secukinumab in the investigator’s opinion. At baseline, patients with previous exposure to secukinumab or any other biologic drug directly targeting IL-17A or IL-17RA, or any investigational drug within 4 weeks (or 5 half-lives, whichever was longer) prior to randomization, or with other active skin diseases or infections affecting the evaluation of psoriasis were excluded. Patients were also excluded if they did not limit UV exposure; used prohibited psoriasis treatments; used cholesterol-lowering medications (unless the use of cholesterol-lowering medications involved a dose that was stable ≥90 days prior to randomization and remained stable during the study); had notable current cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease (e.g., uncontrolled diabetes as evidenced by HbA1c ≥7%, myocardial infarction, or cerebrovascular accident within 6 months before the screening visit, unstable ischemic heart disease) in the investigator’s opinion; had significant medical problems (uncontrolled hypertension with measured systolic ≥180 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥95 mm Hg, congestive heart failure [New York Heart Association status of class III or IV]); had a serum creatinine level of >2.0 mg/dL, a fasting blood glucose ≥150 mg/dL, or a total white blood cell (WBC) count <2500/μl, thrombocytes <100,000/μl, neutrophils <1500/μl, or hemoglobin <8.5 g/dL at screening.

Interventions and follow-up

For the secukinumab group, patients or trained caregivers administered a dose of secukinumab 300 mg (2 subcutaneous injections of 150 mg) once weekly for 5 weeks (at randomization and Weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4), followed by dosing every 4 weeks, starting at Week 8 through Week 48. For the placebo group, patients/trained caregivers administered a dose of placebo (2 injections of the placebo 1 mL pre-filled syringe each containing a mixture of inactive excipients, matching the composition of the secukinumab 150 mg dose) once weekly for 5 weeks (at randomization and Weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4), followed by a dose after 4 weeks at Week 8. From Week 12, all patients in the placebo group were switched to treatment with secukinumab 300 mg. Patients received a dose of secukinumab 300 mg once weekly for 5 weeks (at Weeks 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16) followed by dosing every 4 weeks, starting at Week 20 to Week 48. In order to maintain the blinding during the double-blinded induction period, placebo doses were self-administered by the patients/trained caregivers at Weeks 13, 14, and 15 who were previously on secukinumab treatment in the double-blinded treatment period.

Outcomes

The target to background ratio (TBR) was used to evaluate aortic vascular inflammation. Patients underwent 18-FDG PET/CT scans using the standard protocol (Bural et al., 2008, Chen et al., 2009) following overnight fast, pre-scan glucose level was <150 mg/dL prior to FDG administration. Standard bed positions of three minutes each, scanning whole body were obtained for each patient from the vertex of the skull to the toes 120 minutes after administration of FDG. After qualitative review of PET and CT images, the extent of 18 FDG uptake within the aorta was directly measured by (OsiriXTM) to calculate TBR. Each region of interest produced two measures of metabolic activity: a mean standardized uptake value (SUVmean) and maximal standardized uptake value (SUVmax), and these were obtained in the entire aorta. Moreover, regions of interest were also placed on 6 contiguous slices over the superior vena cava to obtain background activity of the FDG tracer. The SUVmean from each of the superior vena cava slices were then averaged to produce one venous value. In order to account for background blood activity, SUVmax values from each aortic slice was divided by the average venous SUVmean value yielding a target-to-background ratio (Bural et al., 2006, Mehta et al., 2011b, Naik et al., 2015).

The primary objective was to evaluate the effect of secukinumab 300 mg compared to placebo with respect to the change in TBR from baseline at Week 12. TBR was assessed using vascular inflammation imaging by full-body FDG PET/CT at three scheduled visits: baseline, Week 12, and Week 52.

The secondary objectives included the effect of secukinumab compared to placebo on changes from baseline in cardiometabolic markers and PASI 90 and IGA mod 2011 0 or 1 responses at Week 12 and at Week 52 (as exploratory objectives). Cardiometabolic biomarkers included measures of advanced lipoprotein characterization, measures of inflammation, insulin resistance, and markers predictive of diabetes. Serum biomarkers and imaging data were analyzed centrally at the National Institutes of Health (Mehta Lab). The advanced lipoprotein characterization biomarkers included lipid particle size, high-density lipoprotein function (cholesterol efflux); inflammatory markers included TNF-α, IL-6, and CRP; adiposity markers included leptin and adiponectin. Insulin resistance biomarkers included insulin levels/glucose to yield homeostatic model assessment-insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and diabetes predictive biomarkers included apolipoprotein B, ferritin, IL-2 receptor A, IL-18, and fetuin-A.

Clinical safety and tolerability of secukinumab was evaluated by monitoring vital signs, clinical laboratory variables, and AEs. Safety assessments consisted of recording all AEs and SAEs, with their severity and relationship to study drug and pregnancies. The safety assessments also included regular monitoring of hematologic, blood chemistry, and urine tests, and regular assessments of vital signs, physical condition, and body weight.

Sample size

The sample size was based on the change from baseline in the TBR from the aorta. Using a t-test, a clinically important mean treatment difference of 0.15 in TBR, a (common) standard deviation of 0.196, a 2-sided significance level of 0.05, and a power of 0.90, it was determined that approximately 74 patients (37 in each treatment group) were necessary (Bissonnette et al., 2013, Tawakolet al., 2013). Allowing for a loss to follow-up rate of 0.10, approximately 84 patients (42 in each treatment group) were required to be randomized.

Randomization, assignment and masking

Eligible patients were randomized via Interactive Response Technology in a 1:1 ratio to either secukinumab 300 mg or placebo. Patients, investigators/site staff, persons performing assessments, and Novartis study personnel remained blinded to individual treatment assignment from time of randomization until the final database lock at Week 52.

Statistical methods and analysis

The primary efficacy variable was analyzed by an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment, baseline, and body weight (<90 kg, ≥90 kg) as explanatory variables. The randomized set included all patients who were randomized to the treatment groups, the safety set included all patients who received at least 1 dose of study medication, and the full analysis set included all patients to whom study medications were assigned. For the primary efficacy variable, data for patients with missing post-baseline value were not imputed, and patients were included in the analysis if they had both baseline and post-baseline assessments. The primary analysis was based on the full analysis set. Changes from baseline in each cardiometabolic biomarker were analyzed at each time point using the same ANCOVA model as for the primary efficacy variable; missing data were imputed using the last-observation-carried-forward method. In addition, the primary efficacy variable and changes from baseline in each biomarker were analyzed using the stratified Wilcoxon rank-sum test with modified ridit scores (van Elteren’s test), adjusting for body weight. PASI 90 and IGA mod 2011 0 or 1 responses were analyzed at each time point using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, adjusting for body weight, to compare the effect of secukinumab to placebo.

Exploratory analyses were performed to assess the effect of continuous treatment using secukinumab at Week 52 compared to baseline by combining both randomization arms. The primary efficacy variable was analyzed using a linear regression model as well as the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and PASI and IGA mod 2011 responses were summarized using proportions and 95% CIs. Additionally, TBR was analyzed as percent change from baseline using a linear model with treatment as the only explanatory variable. Sensitivity analyses were performed using linear regression models in subgroups defined by clinical treatment responses, BMI, age, CVD risk, or baseline aortic inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Jennifer Steadman and Suzette Baez Vanderbeek for their expert project management and to the patients who volunteered for this study. The authors would like to thank Bitumani Borah and Mohammad Fahad Haroon (Novartis Health Care Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India) for providing medical writing and editorial assistance.

Funding acknowledgement

This study is funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ.

Abbreviations

- BSA

body surface area

- PASI

Psoriasis Area and Severity Index

- IGA mod 2011

Investigator’s Global Assessment modified 2011

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FDG-PET/CT

18F-2-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography

- GlycA

Glycoprotein acetyls

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HDL-C

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-P

high-density lipoprotein particle number

- HDL-S

high-density lipoprotein particle size

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- LDL-C

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-P

low-density lipoprotein particle number

- LDL-S

low-density lipoprotein particle size

- IDL

intermediate-density lipoprotein

- IDL-P

intermediate-density lipoprotein particle number

- VLDL

very low-density lipoprotein

- VLDL-P

very low-density lipoprotein particle number

- L-VLDL-P

large very low-density lipoprotein particle number

- HOMA-IR

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

- PsA

psoriatic arthritis

- TBR

target-to-blood pool ratio

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- IL

interleukin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Availability Statement

Available data are posted on https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT02690701. For further questions regarding the data please contact the primary/corresponding author.

Conflict of Interest

Dr Gelfand served as a consultant for BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen Biologics, Novartis Corp, UCB (DSMB), Sanofi, and Pfizer, receiving honoraria; and receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Novartis, Celgene, Ortho Dermatologics, and Pfizer; and received payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Lilly, Ortho Dermatologics, and Novartis. Dr Gelfand is a Deputy Editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology receiving honoraria from the Society for Investigative Dermatology.

Dr Duffin has received research grants from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Stiefel Laboratories, and UCB; and has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Ortho Dermatologic, Pfizer, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, Stiefel Laboratories, and UCB; and is on the speaker's bureau for Novartis.

Dr Armstrong has served as investigator, advisor, and/or consultant to Leo, AbbVie, UCB, Janssen, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sun, Dermavant, BMS, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Sanofi U.S., Dermira, Modmed, and Ortho Dermatologics, Inc.

Dr Blauvelt has served as a scientific adviser and/or clinical study investigator for AbbVie, Aclaris, Akros, Allergan, Almirall, Amgen, Arena, Athenex, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermavant, Dermira, Eli Lilly, FLX Bio, Forte, Galderma, Genentech/Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Leo, Meiji, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Ortho, Pfizer, Purdue Pharma, Regeneron, Revance, Sandoz, Sanofi Genzyme, Sienna Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharma, UCB Pharma, and Vidac and as a paid speaker for AbbVie, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme.

Dr Trying has conducted studies sponsored by the producer of secukinumab.

Dr Menter has received compensation from or served as an investigator, consultant, advisory board member, or speaker for Abbott Labs, AbbVie, Allergan, Amgen, Anacor, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Dermira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Janssen, Leo, Merck & Co, Neothetics, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Sienna, Symbio/Maruho, UCB, Vitae, and Xenoport.

Dr Gottlieb is currently serving as consultant, advisory board member, speaker for Janssen, Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Beiersdorf, Abbvie, UCB, Novartis, Incyte, Lilly, Reddy Labs, Valeant, Dermira, Allergan, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Xbiotech, Leo, Avotres Therapeutics. Research/Educational Grants: Janssen, Incyte, UCB, Novartis, Lilly Xbiotech, Boeringer Ingelheim.

Dr Lockshin reports personal fees from Lilly, Novartis, Janssen, and Abbott; has served as a speaker for Novartis, Eli Lilly, and Abbvie; conducted research for Celgene, Abbvie, Novartis, Eli Lilly, and Strata, and served as a consultant for Novartis, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Abbive.

Dr. Simpson reports grants from Eli Lilly, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Leo Pharmaceutical, Merck, Pfizer, and Regeneron, and personal fees from Menlo Therapeutics, Valeant, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Dermira, Sanofi Genzyme, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Leo Pharmaceuticals.

F Kianifard, E Muscianisi and J Steadman are employees and/or stockhonlers of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA.

R Sarkar is an employee of Novartis Healthcare Private Limited, Hyderabad, India.

Dr Mehta is a full-time US Government Employee and receives research grants to the NHLBI from AbbVie, Janssen, Celgene and Novartis. J.M.G. in the past has served as a consultant for Amgen, Coherus (DSMB), Dermira, Eli Lilly, Janssen Biologics, Leo Pharma, Merck (DSMB), Novartis Corp, Regeneron, Dr. Reddy’s labs, Sanofi and Pfizer Inc., receiving honoraria; and receives research grants (to the Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania) from Abbvie, Janssen, Novartis Corp, Regeneron, Sanofi, Celgene, and Pfizer; and received payment for continuing medical education work related to psoriasis that was supported indirectly by Lilly and Abbvie.

Dr Shin, Dr Ahlman, Dr Playford, Dr Joshi, Dr Dey, Dr Werner and Dr Alavi have nothing to disclose.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) of University of Utah and University of Southern California.

Study ethics: The study protocol and all amendments were approved by the independent ethics committee or institutional review board of each center. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Role of the sponsor: Novartis served as regulatory sponsor. Dr Mehta’s lab provided the analysis of images and biomarkers. Novartis analyzed the primary and secondary efficacy variables. Dr. Gelfand’s lab replicated the Novartis analyses independently and conducted the exploratory analyses.

Registration of clinical trial: NCT02690701

Date of clinical trial registration: February 24, 2016

Study center(s): The study was conducted at 12 investigative sites in the United States.

References

- Ait-Oufella H, Libby P, Tedgui A. Anticytokine immune therapy and atherothrombotic cardiovascular risk. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2019;39(8):1510–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette R, Harel F, Krueger JG, Guertin MC, Chabot-Blanchet M, Gonzalez J, et al. TNF-alpha Antagonist and vascular inflammation in patients with psoriasis vulgaris: A randomized placebo-controlled study. J Invest Dermatol 2017;137(8):1638–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette R, Tardif JC, Harel F, Pressacco J, Bolduc C, Guertin MC. Effects of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist adalimumab on arterial inflammation assessed by positron emission tomography in patients with psoriasis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Circulation Cardiovascular Imaging 2013;6(1):83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE, Randazzo B, Wasfi Y, Shen YK, et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: Results from the phase III, double-blinded, placebo- and active comparator-controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017;76(3):405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bural GG, Torigian DA, Chamroonrat W, Alkhawaldeh K, Houseni M, El-Haddad G, et al. Quantitative assessment of the atherosclerotic burden of the aorta by combined FDG-PET and CT image analysis: a new concept. Nuclear Medicine and Biology 2006;33(8):1037–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bural GG, Torigian DA, Chamroonrat W, Houseni M, Chen W, Basu S, et al. FDG-PET is an effective imaging modality to detect and quantify age-related atherosclerosis in large arteries. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008;35(3): 562–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W, Bural GG, Torigian DA, Rader DJ, Alavi A. Emerging role of FDG-PET/CT in assessing atherosclerosis in large arteries. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009;36(1):144–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TI-RMRAIRM. The interleukin-6 receptor as a target for prevention of coronary heart disease: a mendelian randomisation analysis. The Lancet 2012;379(9822):1214–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danzaki K, Matsui Y, Ikesue M, Ohta D, Ito K, Kanayama M, et al. Interleukin-17A deficiency accelerates unstable atherosclerotic plaque formation in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2012;32(2):273–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey AK, Joshi AA, Chaturvedi A, Lerman JB, Aberra TM, Rodante JA, et al. Association between skin and aortic vascular inflammation in patients with psoriasis: A case-cohort study using positron emission tomography/computed tomography. JAMA cardiology 2017;2(9):1013–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, Gelfand JM, Lichten J, Mehta NN, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(4):1073–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elnabawi YA, Dey AK, Goyal A, Groenendyk JW, Chung JH, Belur AD, et al. Coronary artery plaque characteristics and treatment with biologic therapy in severe psoriasis: results from a prospective observational study. Cardiovascular Research 2019;115(4):721–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbel C, Chen L, Bea F, Wangler S, Celik S, Lasitschka F, et al. Inhibition of IL-17A attenuates atherosclerotic lesion development in apoE-deficient mice. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950) 2009;183(12):8167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbel C, Chen L, Bea F, Wangler S, Celik S, Lasitschka F, et al. Inhibition of IL-17A Attenuates atherosclerotic lesion development in ApoE-deficient mice. The Journal of Immunology 2009;183(12):8167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayad ZA, Mani V, Woodward M, Kallend D, Abt M, Burgess T, et al. Safety and efficacy of dalcetrapib on atherosclerotic disease using novel non-invasive multimodality imaging (dal-PLAQUE): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet (London, England) 2011;378(9802):1547–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa AL, Abdelbaky A, Truong QA, Corsini E, MacNabb MH, Lavender ZR, et al. Measurement of arterial activity on routine FDG PET/CT images improves prediction of risk of future CV events. JACC Cardiovascular Imaging 2013;6(12):1250–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Hertel B, Koltsova EK, Sorensen-Zender I, Kielstein JT, Ley K, et al. Increased atherosclerotic lesion formation and vascular leukocyte accumulation in renal impairment are mediated by Interleukin-17A. Circulation Research 2013;113(8):965–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM. Commentary: Does biologic treatment of psoriasis lower the risk of cardiovascular events and mortality?: A critical question that we are only just beginning to answer. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;79(1):69–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Neimann AL, Shin DB, Wang X, Margolis DJ, Troxel AB. Risk of myocardial infarction in patients with psoriasis. JAMA 2006;296(14):1735–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Shin DB, Alavi A, Torigian DA, Werner T, Papadopoulos M, et al. A phase IV, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of the effects of ustekinumab on vascular inflammation in psoriasis (the VIP-U trial). J Invest Dermatol 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.07.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelfand JM, Troxel AB, Lewis JD, Kurd SK, Shin DB, Wang X, et al. The risk of mortality in patients with psoriasis: results from a population-based study. Arch Dermatol 2007;143(12):1493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisterå A, Robertson A-KL, Andersson J, Ketelhuth DFJ, Ovchinnikova O, Nilsson SK, et al. Transforming growth factor–β signaling in T cells promotes stabilization of atherosclerotic plaques through an interleukin-17–dependent pathway. Science Translational Medicine 2013;5(196):196ra00–ra00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb AB BA, Langley RG, Meng X, Fox T, Nyirady J. Secukinumab decreases inflammation as measured by hscrp in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and concomitant psoriatic arthritis: Pooled analysis of 4 phase 3 trials American Academy of Dermatology Summer meeting. New York, USA: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, et al. 2018. AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018:25709. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes JE, Chan TC, Krueger JG. Psoriasis pathogenesis and the development of novel targeted immune therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017;140(3):645–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjuler KF, Gormsen LC, Vendelbo MH, Egeberg A, Nielsen J, Iversen L. Increased global arterial and subcutaneous adipose tissue inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. The British Journal of Dermatology 2017;176(3):732–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Shafiq N, Dogra S, Mittal BR, Attri SV, Bahl A, et al. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-based evaluation of systemic and vascular inflammation and assessment of the effect of systemic treatment on inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: A randomized placebo-controlled pilot study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84(6):660–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: Which therapy for which patient: Psoriasis comorbidities and preferred systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(1):27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurd SK, Gelfand JM. The prevalence of previously diagnosed and undiagnosed psoriasis in US adults: results from NHANES 2003-2004. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60(2):218–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, Gordon K, Weglowska J, Puig L, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. The New England Journal of Medicine 2015;373(14):1318–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, On YK, Lee EJ, Choi JY, Kim BT, Lee KH. Reversal of vascular 18F-FDG uptake with plasma high-density lipoprotein elevation by atherogenic risk reduction. J Nucl Med 2008;49(8):1277–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makavos G, Ikonomidis I, Andreadou I, Varoudi M, Kapniari I, Loukeri E, et al. Effects of interleukin 17A inhibition on myocardial deformation and vascular function in psoriasis. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2019. DOI: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta NN, Shin DB, Joshi AA, Dey AK, Armstrong AW, Duffin KC, et al. Effect of 2 psoriasis treatments on vascular inflammation and novel inflammatory cardiovascular biomarkers: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Circulation Cardiovascular Imaging 2018;11(6):e007394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta NN, Torigian DA, Gelfand JM, Saboury B, Alavi A. Quantification of atherosclerotic plaque activity and vascular inflammation using [18-F] fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT). Jove-J Vis Exp 2012;2(63):e3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta NN, Yu Y, Saboury B, Foroughi N, Krishnamoorthy P, Raper A, et al. Systemic and vascular inflammation in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis as measured by [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT): a pilot study. Arch Dermatol 2011;147(9):1031–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, Kivelevitch D, Prater EF, Stoff B, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80(4):1029–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik HB, Natarajan B, Stansky E, Ahlman MA, Teague H, Salahuddin T, et al. Severity of psoriasis associates with aortic vascular inflammation detected by FDG PET/CT and neutrophil activation in a prospective observational study. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2015;35(12):2667–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. The New England Journal of Medicine 2009;361(5):496–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe MH, Shin DB, Wan MT, Gelfand JM. Objective measures of psoriasis severity predict mortality: A prospective population-based cohort study. J Invest Dermatol 2018;138(1):228–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papp KA, Leonardi C, Menter A, Ortonne JP, Krueger JG, Kricorian G, et al. Brodalumab, an anti-interleukin-17-receptor antibody for psoriasis. The New England Journal of Medicine 2012;366(13):1181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, Ashcroft DM, Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133(2):377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaci D, Crowley JJ, Ryan C, Krueger JG, et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double-blind, active-comparator-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;394(10198):576–586. Erratum in: Lancet 2019 Jul 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. The New England Journal of Medicine 2017;377(12):1119–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rungapiromnan W, Yiu ZZN, Warren RB, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Impact of biologic therapies on risk of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with psoriasis: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. The British Journal of Dermatology 2017;176(4):890–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajja AP, Joshi AA, Teague HL, Dey AK, Mehta NN. Potential immunological links between psoriasis and cardiovascular disease. Front Immunol 2018;9(1234):1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon T, Taleb S, Danchin N, Laurans L, Rousseau B, Cattan S, et al. Circulating levels of interleukin-17 and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal 2012;34(8):570–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Prasad K-MR, Butcher M, Dobrian A, Kolls JK, Ley K, et al. Blockade of interleukin-17A results in reduced atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein; deficient mice. Circulation 2010;121(15):1746–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockinger B, Omenetti S. The dichotomous nature of T helper 17 cells. Nature Reviews Immunology 2017;17:535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober B, Leonardi C, Papp KA, Mrowietz U, Ohtsuki M, Bissonnette R, et al. Short- and long-term safety outcomes with ixekizumab from 7 clinical trials in psoriasis: Etanercept comparisons and integrated data. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2017;76(3):432–40.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara N, Kai H, Ishibashi M, Nakaura H, Kaida H, Baba K, et al. Simvastatin attenuates plaque inflammation: evaluation by fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48(9):1825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshita J, Mohler ER, Krishnamoorthy P, Moore J, Rogers WT, Zhang L, et al. Endothelial cell-, platelet-, and monocyte/macrophage-derived microparticles are elevated in psoriasis beyond cardiometabolic risk factors. Journal of the American Heart Association 2014;3(1):e000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawakol A, Fayad ZA, Mogg R, Alon A, Klimas MT, Dansky H, et al. Intensification of statin therapy results in a rapid reduction in atherosclerotic inflammation: results of a multicenter fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography feasibility study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62(10):909–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Es T, van Puijvelde GHM, Ramos OH, Segers FME, Joosten LA, van den Berg WB, et al. Attenuated atherosclerosis upon IL-17R signaling disruption in LDLr deficient mice. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2009;388(2):261–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Stebut E, Reich K, Thaci D, Koenig W, Pinter A, Körber A, et al. Impact of secukinumab on endothelial dysfunction and other cardiovascular disease parameters in psoriasis patients over 52 weeks. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2019;139(5):1054–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan MT, Shin DB, Hubbard RA, Noe MH, Mehta NN, Gelfand JM. Psoriasis and the risk of diabetes: A prospective population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78(2):315–22 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.