Abstract

It is well accepted that the tumor microenvironment plays a pivotal role in cancer onset, development, and progression. The majority of clinical interventions are designed to target either cancer or stroma cells. These emphases have been directed by one of two prevailing theories in the field, the Somatic Mutation Theory and the Tissue Organization Field Theory, which represent two seemingly opposing concepts. This review proposes that the two theories are mutually inclusive and should be concurrently considered for cancer treatments. Specifically, this review discusses the dynamic and reciprocal processes between stromal cells and extracellular matrices, using pancreatic cancer as an example, to demonstrate the inclusivity of the theories. Furthermore, this review highlights the functions of cancer associated fibroblast, which represent the major stromal cell, as important mediators of the known cancer hallmarks that the two theories attempt to explain.

Introduction

Technological advances, such as whole genome and single cell sequencing, have deepened our understanding of cancer pathophysiology. As a result, these advances have facilitated breakthroughs in drug development, which have significantly prolonged survival and improved the quality of life for numerous patients. However, the lack of a uniform patient response to therapeutics, along with the national and global rise in cancer incidence and mortality [1, 2]; reveal the limitations in our understanding of tumor biology. To address these limitations, a framework by which the functional complexities of cancer could be studied was established and collectively referred to as the Hallmarks of Cancer [3, 4].

Cancer hallmarks describe normal physiological processes that are inappropriately instigated and/or terminated due to embellished/altered regulation of the tissues’ homeostatic equilibrium. Healthy tissue homeostasis is typically maintained via a coordinated balance between intrinsic (i.e., intracellular) programs and extrinsic (i.e., extracellular matrix -ECM-, growth factor availability, and more) factors. When the balance between the cell and its collective microenvironment is perturbed, the system initiates discrete programs that, in the case of cancer, enable cells to acquire growth and survival advantages such as sustained proliferation, restrained cell death and the ability to metastasize. For most cancers, this is a common theme that is often exploited by anti-cancer therapies, which are designed to interfere with cancer hallmarks. While there has been much success in some cancers with this treatment approach, the development of drug resistance and cancer recurrence remain among the major concerns [5]. The revised hallmarks of cancer [3], together with these challenges, highlight the fact that cancer involves more than just mutational cell transformation and cell-intrinsic programs. In fact, the hallmarks suggest that tumorigenesis consists of a conglomerate of rather complex, dynamic, and reciprocal systems amid cancer cells and their microenvironment [6], which continuously evolve in response to homeostatic perturbations. Taken together, this suggests that cancer hallmarks are both drivers and consequences of tumorigenesis to which the role of the tumor microenvironment is central to both disease initiation and progression. To support this notion, we highlight the two prevailing theories that attempt to explain the process of tumorigenesis: Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT) and the Tissue Organization Field Theory (TOFT). We then unify the two theories, to emphasize these are mutually inclusive. Finally, we depict the functional reciprocity between one of the major stromal cells, cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs), and the ECM they produce, to highlight the role of CAFs in tumorigenesis accounting for the Cancer Hallmarks explained by SMT and TOFT.

Prevailing Theories of Tumorigenesis: SMT vs TOFT

Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT)

The premise of the Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT) was first established by Theodor Boveri, who described cancer as a disease solely driven by specific permanent changes in chromatin complexes that prompt mature cells to continuously divide [7, 8]. As additional prominent genetic discoveries were made, Boveri’s theory was later refined to state cancer ensued from driver mutations in DNA that cause gain (oncogenes) or loss of function (tumor suppressor genes), which altogether promote accelerated cell growth [9–12]. The idea that cancer is instigated by “driver mutations” has led researchers to query the required mutational load for cancer to initiate, whereby the Knudson hypothesis proposed that a minimum of two genetic alterations are needed for cancer to develop [13]. Boveri’s SMT was further strengthened by the demonstration that increased frequency of mutational burden strongly correlates with cancer aggressiveness [9–12, 14, 15]. SMT states that cancer is a cellular based disease in which explicit genetic mutations give rise to tumors due to intrinsic loss of cell regulatory programs that induce cell proliferation and/or alter cell differentiation [4, 16].

The SMT is highly revered in the cancer field and has rendered enormous leaps in our understanding of malignant diseases as well as in the development of targeted therapies. However, this theory does not fully explain all aspects of cancer. For instance, SMT does not explicate why neoplasms of inheritable cancers only develop in specific organs when the “germline” mutation exists in every cell [17–20]. More importantly, the SMT model suggests that cancer is irreversible in that mutated cells remain committed to malignant transformation (despite external stimuli). However, tumor regression (spontaneous and intervention based) is evident, in spite of the presence of tumor promoting mutations [11, 21–25]. Considering two of the most broadly used cancer interventions (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) are considerably effective in reducing tumor growth, often indiscriminate of driver mutations, dampens the validity of this SMT claim. [21, 26–28].

SMT seems insufficient for explaining functional variations imparted solely by altering cell culturing conditions [28–30]. For example, a groundbreaking study examined morphological and proliferative rates of a tumorigenic cell-line and its non-tumorigenic breast epithelial precursor. In this study, cells were initially cultured using classic culturing conditions (i.e., in 2D), where little differences in morphology and proliferation were apparent. However, when the same cells were cultured using a three-dimensional (3D) culturing system that mimics the in vivo environment, differences became apparent between non-tumorigenic and tumorigenic cells. This study, and others, ultimately revealed the importance of including microenvironmental appropriate conditions for the study of normal vs. malignant cells [31]. Collectively, these findings bring to light that in addition to genetic alterations, there are extrinsic factors that also influence tumorigenic programs. The tissue organization field theory (TOFT) takes these observations into consideration.

Tissue Organization Field Theory (TOFT)

The premise of TOFT began with careful histological observations of tumor tissue. Pathologists observed that tissues, and not just cancer cells, lacked the “normal” defined physiological architecture. This observation established the basis for pathology-informed diagnosis and led German scientists to define cancer as a tissue-based disease prior to Boveri’s cell-based speculation [32]. TOFT was thereafter framed to state that cancer is a systemic disease and suggests that proliferation is the default state of cells regulated by the local microenvironment [33, 34]. Hence, TOFT considers the dynamic and reciprocal relationship between cancer cells and their microenvironment, also known as the stroma, to be essential in restraining or promoting tumorigenesis. Of note, renewed interest in considering TOFT arose from the recent excitement generated by anti-cancer immune therapies.

Additionally, TOFT is further supported by studies where stromal cells of the primary tumor, which lack oncogenic or tumor suppressive mutations, were found to enhance the metastatic potential of the cancer cells [28, 35]. Likewise, stromal influences became evident in experiments that observed local tissue aggravation suffices to enable tumor development. In these studies, mammary fat pads were pre-cleared from epithelial components (i.e., leaving only the stroma) and subjected to ionizing radiation. After radiation, treated fat-pads were repopulated with un-irradiated non-tumorigenic epithelial cells, which consequently developed tumors. Results revealed that radiation-activated stroma promotes tumor formation in otherwise non-tumorigenic cells [36]. Additionally, Maffini et al., conducted an experiment involving isolated stroma and epithelial cells from rat mammary glands treated with a known carcinogen. The cells and/or stroma were separately treated with carcinogen/irritant, and then recombined to determine which of the treated cellular components would induce tumorigenesis. From this study, researchers found that neoplasms only developed in animals whose stroma was exposed to the treatment. Maffini et al., observed that animals whose stroma was not exposed to treatment (i.e., stroma exposed to vehicle only) did not develop neoplasms, regardless of whether the epithelial cells were exposed to the carcinogen [37]. These and similar studies went on to suggest that neoplastic development and progression is restricted by normal/naive stroma, while it is tolerated and often enabled by an altered microenvironment (i.e., tumor permissive) that includes both activated stromal cells and a remodeled ECM, akin to chronic wounds [37–44].

These types of observations are addressed in TOFT, which suggests that the healthy stroma imposes constraints on cells and that loss of these environmental constraints (i.e., a result of chronic stromal alterations, remodeling or damage), enable cancer onset and progression [30]. Evidence for this was reported in 1910 by Rous who suggested that the tumor problem is a tissue predicament [45]. When considering normal embryonic development, TOFT aligns with the current view that the role of the mesenchymal stroma, represented by fibroblastic cells, is to impart a tightly controlled environment upon epithelial cells, and that the stroma becomes altered during (and/or to initiate) tumorigenesis. In other words, the “normal” stroma balances tissue growth/regeneration by, for example, permitting cell proliferation solely during temporary assaults (i.e., acute wounds), and restoring restraint of cell growth following wound resolution [46–49]. However, instances such as chronic inflammation and cancer, can impede restoration of an “innate” homeostatic state and thus perpetuate regenerative cues of unrestraint cell growth [44, 50]. When this occurs, stromal components collectively evolve to establish a “new” equilibrium that consequently maintains a constitutively, pathological tissue regeneration condition that sustains (or enables) tumorigenesis [43, 51–53]. Another principle of TOFT, supported in Rous’ early observations [45], states that by “normalizing” stromal components (e.g. restoring the initial homeostatic tissue balance) cancer can be restrained and even reversed [33]. Several studies have demonstrated the involvement of epithelial cancer cells and normal stromal cells (i.e., local mesenchymal/fibroblastic cells) in influencing cancer development and progression. For example, Mintz and colleagues demonstrated that teratoma/carcinoma cells can be reprogrammed to give rise to normal adult tissue when injected into intact blastocysts. Follow-up studies from this group also demonstrated that the initial tumor cells were able to contribute to different cell lineages with normal functioning progeny, despite their oncogenic driver mutations and their ability to grow tumors when inoculated into in vivo permissive environments [25, 54]. These findings were later supported by McCullough et al., who observed tumorigenic liver cells differentiate into normal hepatocytes when injected into the liver (i.e., stroma) of healthy rats [55]. Similar results were achieved when a carcinogenic transformed epithelial cell-line was injected into the stroma of mammary glands and was observed to participate in normal development of the mammary gland. This study again highlighted the fact that despite the tumorigenic properties of the epithelial cells, normal stroma can guide tumor cells to not only participate in normal development, but also to produce progeny that contributes to typical/physiological tissue growth [56]. These studies suggested that the plasticity of malignant cells enables “reversal to normalcy” such that cells can potentially differentiate in a non-pathological manner and incorporate into healthy, functional tissues/organs [54]. These studies demonstrated that unaltered natural stromal is restrictive of tumor growth while alterations in stromal cells, such as activation of local fibroblastic cells (i.e., generating CAFs), and chronic concomitant remodeling of CAF generated interstitial ECM [57, 58], alter the microenvironment to endorse or to at least tolerate tumor development and progression. These studies suggest that the normal tissue architecture, often regulated by local fibroblastic cells, can reinstate regulatory controls in epithelial/solid cancer cells [59–64].

SMT and TOFT: Mutually inclusive tumorigenic theories

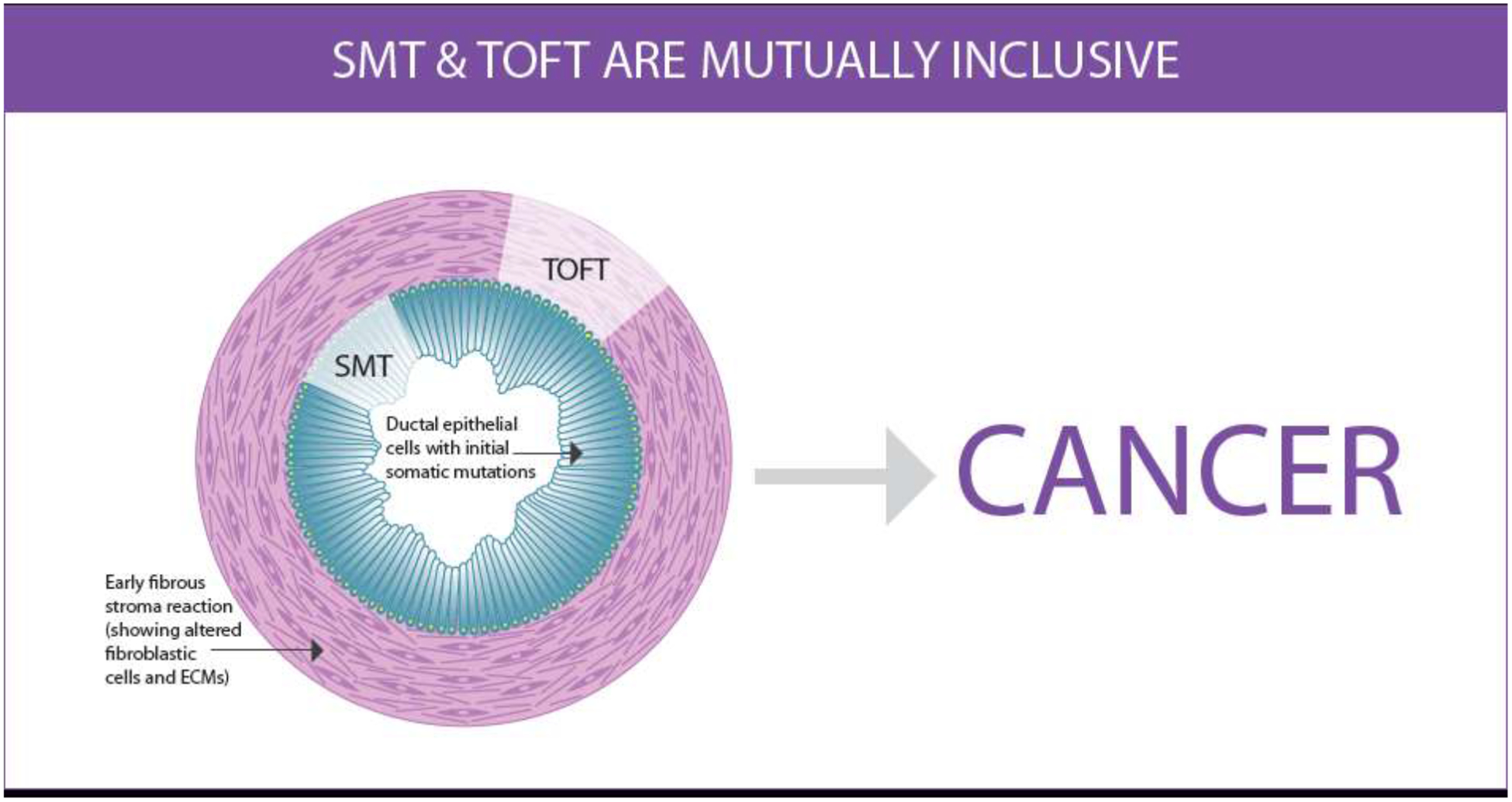

At first glance, TOFT appears to address centuries of experimental and clinical observations most accurately regarding tumorigenesis in comparison to SMT. However, we interpret the underlying concepts of both theories to be mutually inclusive in that both “shed light” on diverse aspects of tumorigenic processes (Figure 1). Together, both theories provide strong rationale that explains the complexities of tumor biology in that mutations in epithelial cancer cells and the stromal microenvironment are actively involved in driving all aspects of epithelial tumorigenesis. For example, early experimental studies demonstrated that tissue formation during development, such as in mammary gland development, is guided by the mesenchyme [65]. Likewise, the rate of tumor foci formation is heavily dependent on mesenchymal stromal cells (i.e. naïve fibroblasts vs. CAFs) and their concurrent ECM [66, 67]. Reciprocally, the stroma is also regulated by changes in cellular programs, which can be instigated by accompanying mutated/malignant epithelial cells and/or injury [43, 65]. Uncontrolled cell proliferation is often accompanied by a loss of normal tissue architecture [68, 69]. In fact, both cancer cells and stroma cells secrete matrix modulating proteins, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue serine proteases, which are known to degrade the basement membrane and remodel the interstitial (i.e., fibroblastic) ECM, thereby altering ECM topography [70, 71]. Dysregulation of ECM turnover is believed to actively promote cancer onset, which can both stimulate mutagenesis (evidence for SMT) and/or provide growth advantage to cells with mutations (in support of TOFT). This was demonstrated in studies in which matrix degrading enzyme, stromelysin-1 induction was shown to activate the stroma such that the reactive stroma induced tumorigenesis [72–75]. Importantly, while cancer cells produce some ECM, the majority of ECM detected in the tumor milieu is generated by CAFs [76]. Thus, a comprehensive (i.e., mechanistic) understanding of CAF function and regulation, including de novo ECM production and remodeling, is necessary to achieve clinically relevant interventions aimed at restoring the anti-tumor regulation of the stroma [77]. Notably, concepts presented in SMT and TOFT regarding tumorigenesis should be strongly considered to aid our understanding of cancer dynamics as well as in the design of effective therapies. As such, this review focuses on the role of the stromal cells; particularly on the reciprocity between activated and wound healing-like fibroblasts (i.e., CAFs) and their self-generated ECMs in promoting and/or sustaining tumor supportive programs (Figure 2).

Figure 1: SMT and TOFT are mutually inclusive.

The Somatic Mutation Theory (SMT) premise is that mutations in tumor suppressor and/or oncogenes in cancer cells are the drivers of tumorigenic programs (cancer hallmarks), such as uncontrolled proliferation and cell invasion. The Tissue Organization Field Theory (TOFT) posits that the stroma dictates tumorigenesis regardless of cell mutations. TOFT explains that breakdowns or changes in stromal constraints, whether due to damage and/or pro-tumor stroma remodeling, enable tumorigenic programs to develop. However, many studies have demonstrated that cancer hallmarks can be dynamically and reciprocally driven by principles underlying both SMT and TOFT. The example provided intends to depict an early low grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasm (PanIN) lesion that indicates potential for cancer development. It “sheds light” on altered/mutated ductal epithelial cells with typical elongated cell bodies (cyan) and sustained nuclear polarity (yellow) highlighting SMT, as well as on activated fibroblasts (CAFs) with aligned CAF-generated ECM, depicted in the stroma (light magenta), to highlight TOFT. Illustration by P. Ovseiovich, Mexico, DF.

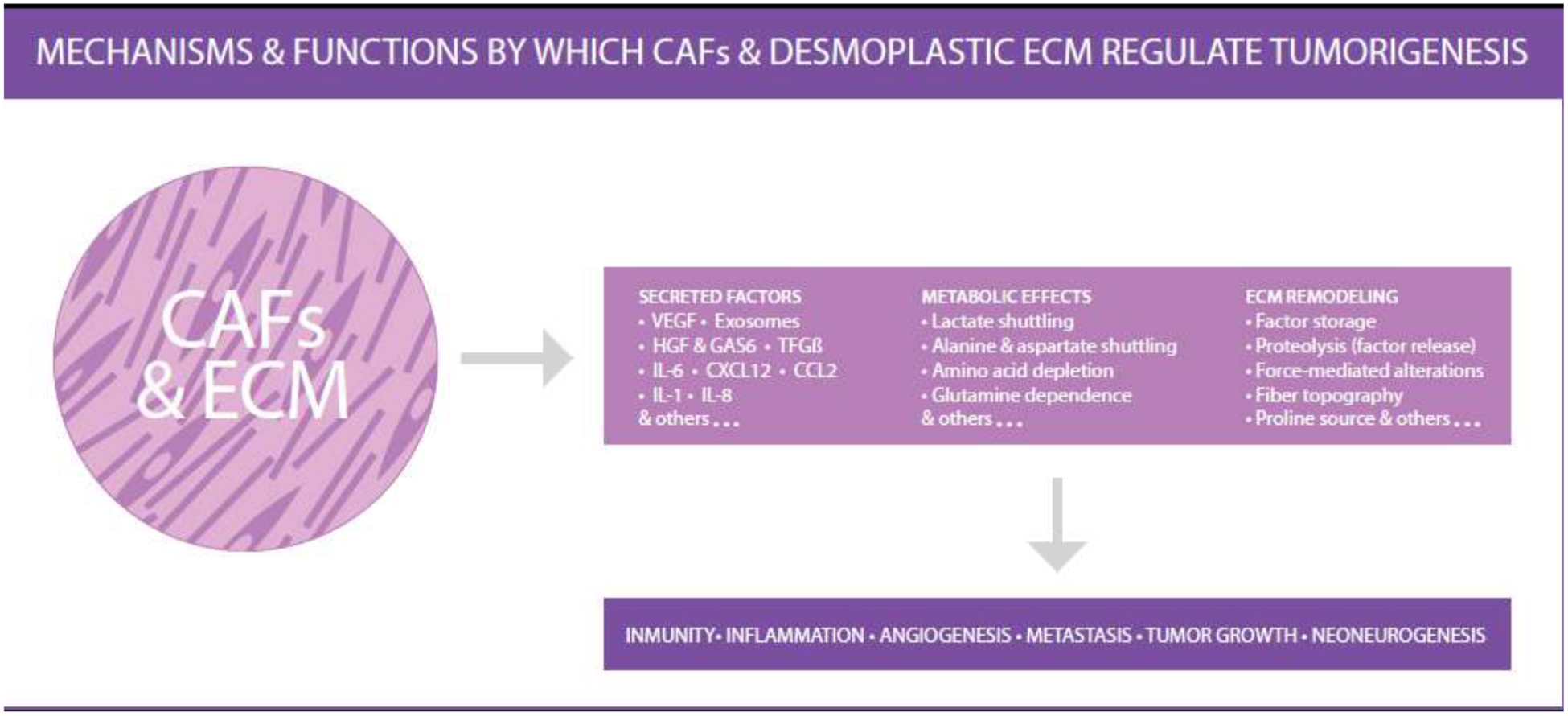

Figure 2: Mechanisms and functions by which CAFs and desmoplastic ECM regulate tumorigenesis.

This illustration highlights the fact that stromal dynamic reciprocity, between CAFs and ECM, controls CAF functions through mechanisms that alter numerous aspects of tumorigenesis such as tumor immunity, systemic inflammation, angiogenesis, metastasis, tumor growth and local neoneurogenesis (i.e., de novo microenvironmental innervation). The illustration includes a partial list of CAF functions as well as some of the mechanism by which these functions are achieved. The illustration highlights the fact that ECM regulated CAF function results in: secretion of distinct key factors, alteration of the metabolic state of the tumor, and the generation of a remodeled interstitial ECM, which together are active participants of all aspects of tumorigenesis. Note that this illustration was inspired by a figure displayed in Sahai et. al., Nat Rev Cancer 2020 [77]. Illustration by P. Ovseiovich, Mexico, DF.

Stromal Dynamic Reciprocity of Cancer

Maintenance of a “normal” tissue homeostatic equilibrium relies on the dynamic and reciprocal influences of stromal elements that collectively dictate tissue structure and physiology. Stromal dynamic reciprocity (SDR) of cancer highlights the biophysical and biochemical interactome amid stromal cells and extrinsic components; primarily between CAFs and the local ECM [38–40, 78]. These interactions are not restricted solely to tumor biology, albeit this dynamic reciprocity persists during tumorigenesis [78]. In normal development, fibroblasts are known to regulate tumor restrictive programs by reinstating balance between intrinsic and extrinsic occurrences in response to growth demands or temporary assaults [43, 44]. Thus, in instances of chronic inflammation like in cancer, in which a new homeostatic balance is achieved, it is not surprising to observe that activated fibroblast, such as CAFs, and their altered ECM, regulate disease programs (Figure 2) [77]. However, in cancer, the roles of CAFs is quite paradoxical in that CAFs present with multiple functions that both support and restrict tumor development and progression [77, 79]. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the best examples to discuss this conundrum due to the complexity and notably vast PDAC stroma (Figure 3) [80–84].

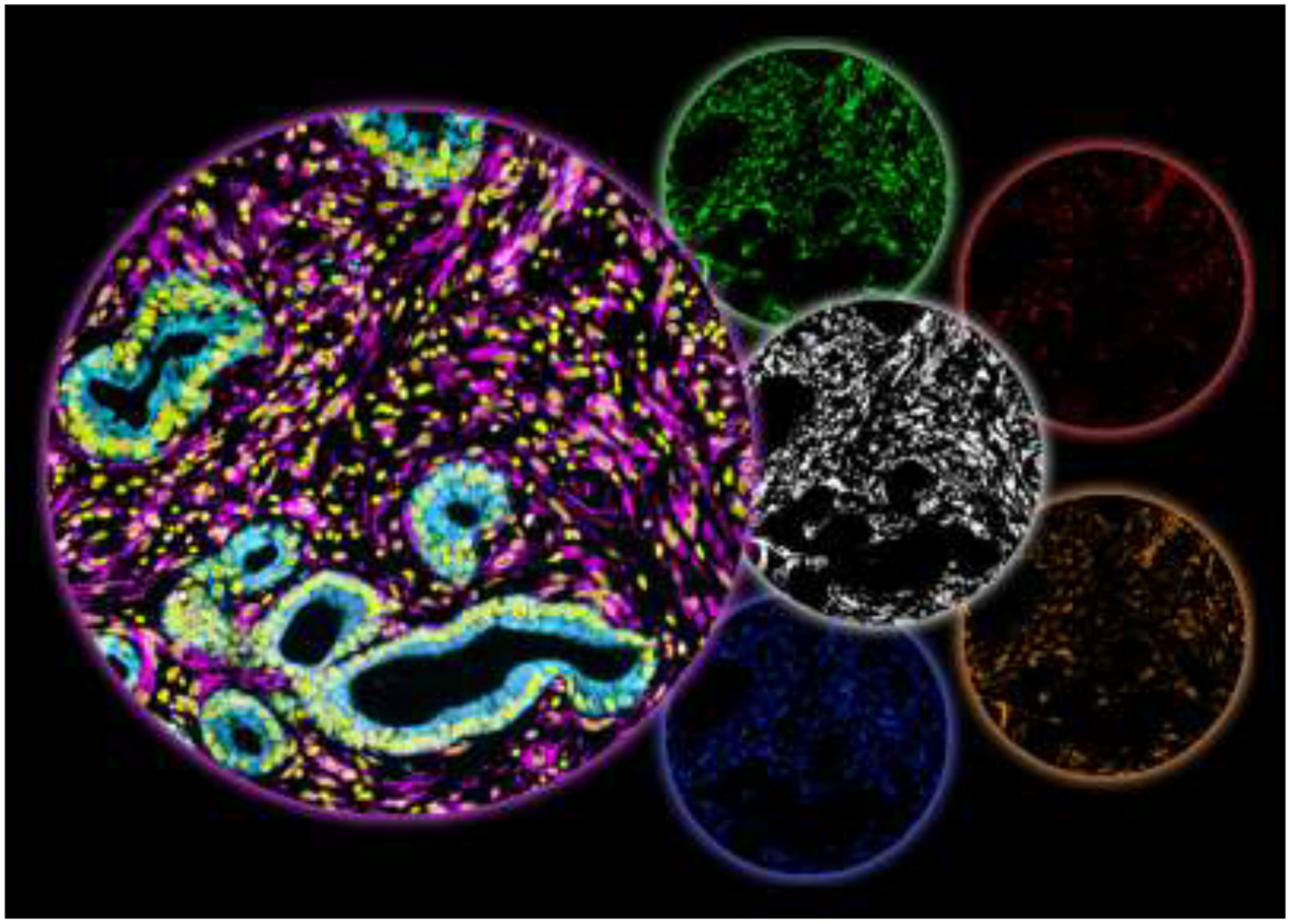

Figure 3: Human PDAC; “gating” on desmoplasia.

Simultaneous multiplex immunofluorescence of human PDAC surgical sample. The large left circle includes 3, of the 7 colors used to indicate: epithelial/tumor areas in cyan, stromal/desmoplasia areas in magenta, and cellular nuclei in yellow. The desmoplastic area, generated by the SMIA-CUKIE 2.1.0 algorithm, is shown in the white middle circle and corresponds to the magenta area. This area was used by the software to “gate” on desmoplastic/stromal positive pixels while excluding all other areas. Using desmoplastic “gating” the last 4 circles show 4 biomarkers that together depict a pro-tumoral stroma signature that is regulated by PDAC associated CAFs and ECM (figure relates to study by Franco-Barraza et. al. 2017 [84]). The 4 stromal biomarkers correspond to: the activated conformation of α5β1-integrin (green), 3D-adhesions (red) enriched in activated focal adhesion kinase (i.e., pFAK in orange), and activated SMAD (blue; indicative of canonical TGFβ1 signaling. This stromal signature was correlated with short overall survival in PDAC as well as in renal cell carcinoma patients.

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and its Associated Fibroblasts

PDAC will soon be the 2nd leading cause of cancer related deaths in the United States [2]. There are several defining characteristics of PDAC. These include evidence of progressive precancerous lesions with oncogenic mutations [85] that are accompanied by significant local stromal alterations [86, 87] (Figures 1 and 3). PDAC is also recognized by its early cancer cell dissemination [88], substantial metastatic events despite locally collapsed nonfunctional blood vessels [89, 90], immune evasion [91, 92], reprogrammed cellular metabolism [93], and a notably expansion of a fibrotic-like stroma reaction, known as desmoplasia [94, 95]. Desmoplasia constitutes the bulk of the tumor mass (Figure 3) and is primarily driven by the SDR events between CAFs and CAF-generated ECM [76, 96, 97].

Numerous studies have demonstrated a symbiotic relationship between PDAC cells and its associated stroma (i.e., PDAC’s desmoplasia). For example, conditioned media from pancreatic CAFs were shown to desensitize PDAC cells to radiation and chemotherapy while also stimulating cancer cell growth, proliferation, migration, and invasion [98]. Moreover, co-injection of cancer cells and CAFs in immunocompromised mice not only increased tumor growth rates, but phenocopied some key human PDAC pathologies [99]. While normal stroma is clearly tumor restrictive, these studies highlight the significance of PDAC associated desmoplastic stroma in promoting tumorigenesis.

To this end, the level of pro-tumor stromal activation was proposed, by more than one study, to serve as a prognostic marker for PDAC disease recurrence [84, 100]. Figure 3 highlights a recent example whereby four CAF biomarkers, regulated by the CAF-generated ECM, constitute a stromal signature indicative of patient outcomes [84]. Another study defined the levels of stroma activity as an activated “stromal index” in which patients were stratified based on the ratio of alpha smooth muscle (αSMA) positive fibroblast (i.e., myofibroblast) to the amount of fibrillar collagen deposition. Accordingly, a high myofibroblastic ratio was found to correlate with decreased patient survival whereas high collagen deposition, in the absence of αSMA, significantly correlated with enhanced overall patient survival [100]. In addition to the above-listed studies, some investigators have highlighted the role of fibroblast activation protein (FAP) positive CAFs in pro-tumoral function [101], while others demonstrated that CAF elimination enhances PDAC progression [102, 103]. Together, these types of studies provide the possible notion of desmoplasia playing a dual role in PDAC progression. In other words, these studies emphasize that the role of the tumor microenvironment can enable both tumor-permissive and tumor-restrictive functions. Thus, untangling the mechanisms regulating pro and anti-tumor programs amid the desmoplastic stroma, may provide insight into harnessing the anti-tumor functions for more effective therapeutic intervention. Ultimately, this positions the SDR between CAFs and the ECM, which is needed to sustain CAF functions [84, 100], as an important constituent of the biology of human PDAC.

Cancer Associated Fibroblast: Major Stromal Architects

The term “CAF” is generally used to describe the activated (i.e., no longer quiescent) fibroblastic cell population that accompanies solid epithelial tumors [77]. CAFs are stromal fibroblastic cells that undergo phenotypic and functional changes and to regulate a plethora of tumorigenic processes (Figure 2) [77]. Fibroblastic activation, akin to wound healing, can occur in response to a disturbance that temporarily alters the resting homeostatic equilibrium [43]. In this case, the main function of an activated fibroblast is to build and remodel the ECM and thus heal the temporary wound. Yet, if the assault prevails, like in the case of cancer, fibroblastic activation (i.e., in the form of CAFs) is sustained along with the ECM remodeling process [43]. An interesting occurrence in desmoplasia, is that naïve/quiescent fibroblastic cells can be activated in response to the ECM deposited by CAFs [104]. In fact, differences amid ECM components have been shown to provide CAFs with distinct phenotypes [105]. Of interests, alterations to ECM that result in fibroblastic activation, can also include physical changes to the ECM, like in the case of increased collagen crosslinking, which in turn could control metastatic events [57]. Further, fibroblastic cell activation resulting in altered ECM deposition, can also be induced by secreted factors [44, 77, 106]. These processes are often controlled by cytoskeletal rearrangements, mediated by cytoskeletal regulatory proteins, which modify morphology and function of fibroblastic cells [69]. One such case is evident when studying the nuclear protein myocardin-related transcription factor A (MRTF-A), which is retained in the cytoplasm by binding to globular actin (G-actin). Upon mechanical stretching of the cell, MRTF-A dissociates from G-actin and translocates to the nucleus [107]. Under low G-actin or during biomechanical stretching conditions, the accumulation of nuclear MRTF-A triggers the expression of cytoskeletal-organizing proteins, like α-SMA, providing the cell with the ability to contract [108]. The newly acquired contractile forces, if sustained like in the case of CAFs, tend to enable the production of an altered/remodeled ECM [109]. The discrete ECM production is accompanied by the deposition of large amounts of collagen I and particular fibronectin splice variants (i.e., EDA fibronectin), amid others [44, 47, 94, 110, 111].

Mutations in SMAD4 are common occurrences in PDAC and result in the desensitization of cancer cells to secreted TGFβ, thereby directing this factor’s effects to stromal cells. Again, this example highlights that both SMT and TOFT are needed to elucidate tumor stroma interactions. Of note, TGFβ1 is secreted in a latent form and it is stored, inactive, within the local ECM. TGFβ1 can be released from its latent complex by fibroblastic (myofibroblastic) cell contraction [112], integrin-dependent mechanisms [106], and more [113]. Once processed (i.e., released), TGFβ1 functions locally and engages its receptor, expressed in stromal fibroblastic cells (i.e., CAFs), to continuously promote fibroblastic activation. The resultant CAFs increase ECM production and together with other cell local factors remodel the ECM, via proteases (i.e., MMPs), matrix cross-linkers such as lysyl oxidase, and/or other proteins such as osteonectin (also known as SPARC), periostin, and hyaluronic acid; all of which are essential for the production of the interstitial ECM that accompanies tumors. Ultimately, these processes establish a vicious cycle of desmoplastic expansion believed to physically and/or biochemically hinder therapeutic intervention [44, 47, 77, 78, 114].

Emphasis on how CAF Function is Mediated by Cytoskeletal Rearrangements

As hinted above, ECM regulated cytoskeletal (and other) changes provide more than just structural support to cells [115, 116]. The cytoskeleton is dynamically regulated to facilitate cell polarity/organization, migration, and division [115, 117, 118]. Together with the main ECM receptors, integrins, the cytoskeleton serves as a mechano-transductor and signaling scaffold that bi-directionally transmits intracellular and extracellular cues [69, 118, 119]. As such, abnormalities in cytoskeletal organization and regulation are associated with diseases including cancer [120–122]. For example, regulated by cytoskeletal changes, alterations in nuclear architecture, a known pathological characteristic of cancer, are attributed to changes in lamin A/C isoform ratios [123–126].

Cytoskeletal organizing proteins are commonly associated with disease progression in many cancers [127]. Interestingly, during myofibroblastic activation, CAFs are known to upregulate cytoskeletal proteins such as α-SMA, palladin, and others. Palladin is a scaffolding protein that is associated with disease progression and unfavorable patient outcomes [128]; especially among epithelial cancers rich in desmoplastic stromal interactions such as PDAC [86, 129–132]. For example, palladin is upregulated in early precancerous lesions and its expression increases during malignant transformation [129, 130, 133–135]. Further, desmoplastic ECM production is facilitated by cytoskeletal rearrangements mediated in part by palladin [110, 132, 136–140]. Moreover, palladin was identified as an independent prognostic marker in PDAC and serves as a potential prognostic biomarker following chemo radiation [132]. Thus, unveiling the role of palladin in pro-tumor stroma dynamics is necessary to therapeutically harness the tumor restrictive stromal properties. Importantly, palladin overexpression is robust in PDAC stroma, in comparison to PDAC cells, and is a conserved feature of desmoplasia [131]. Hence, stromal palladin may play a role in PDAC development, as well as other cancers.

In addition to palladin, α-SMA is often found to be highly upregulated in malignant diseases [141–144]. α-SMA is one of six actin isoforms that enable cells to appropriately respond and adapt to the dynamic microenvironment [145–147]. While in some instances, α-SMA expression is a mere consequence of tumor progression, α-SMA is also upregulated during precancerous conditions, such as inflammation [148]. Although α-SMA expression is known to be regulated by TGFβ1 (i.e., in a smad3 dependent manner), the mechanism by which α-SMA expression contributes to tumorigenesis, in both tumor and stromal cells, remains elusive. In fact, specifically targeting α-SMA expressing cells in PDAC resulted in accelerated progression of this disease [103]. This suggests that α-SMA positive CAFs may also restrain tumor growth and metastasis. Nevertheless, CAF contractile roles are central in generating the earlier noted pro-tumoral anisotropic topography of the desmoplastic ECM.

In PDAC, the desmoplastic ECM includes high volumes of the known aligned “tumor associated collagen signatures 2 and 3” (TACs 2 & 3) [149–151], which positively correlate with poor patient outcomes [109, 152, 153]. ECMs enriched in TACs 2 & 3 are produced by contractile CAFs (i.e., α-SMA positive CAFs), but not by their normal fibroblastic cell counterparts [104]. Of interest, the ECM has been referred to as a fundamental mediator of cell function [116]. It is therefore not surprising that changes in ECM can affect chromatin and gene expression [154]. In fact, ECM dynamics participate in all the hallmarks of cancer [155]. Multiple studies have characterized cytoskeletal regulating Rho GTPases working synergistically through feedback loops and mutual activation/inhibition to control the (fibroblastic) cell morphodynamics [156, 157]. Then again, fibroblastic proteins that regulate the function of Rho GTPases during CAF contraction have been proposed to enable changes in clinically relevant ECM topography (i.e., TACs 2 & 3) [153, 158, 159]. In fact, Rho GTPase regulators, like GEF-H1, were shown by the late Dr. Keely to mediate Rho activation in response to matrix stiffness [160, 161]. Also, when fibroblastic cells contract within a fibrillar ECM, the motility of immune cells (i.e., macrophages) is modified [162]. Thus, CAF contractile functions that alter the ECM are of paramount importance for desmoplastic activation and desmoplastic field expansion. This idea is fully supported by the above mentioned SDR concept, suggesting a central role for actin regulated fibroblastic contraction and ECM interactions in tumor onset and progression [38, 78, 109, 153, 161]. For SDR to occur and be maintained, ECM production and remodeling, as well as the contractile function of CAFs, are essential.

Functional Roles of CAFs in Cancer

One of the best ways to describe CAFs is using an analogy to the sustained force-dependent contractile granulose reaction (i.e., contractile connective tissue) that is evident in chronic wounds [43]. Using this analogy, CAFs present with several functions (Figure 2) [77]. The best known CAF role is described by contractile myofibroblastic CAFs, known to be induced by TGFβ1 (often through cytoskeletal alteration) to produce the typically described pro-metastatic ECM [57, 77, 153, 161]. It is therefore not surprising that investigators recently found that particular posttranslational modifications, in key ECM proteins, profoundly alter integrin clustering to improve stromal cell invasion in wounds [163]. CAFs are also recognized as microenvironmental cells that provide metabolic support to cancer cells (i.e., promoting tumor cell growth under nutritional stress) [93, 164] as well as cells that regulate angiogenesis through secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor [165]. CAFs are also immuno-modulatory cells with both immunosuppressive and immunogenic functions [81, 82, 166, 167]. In fact, inflammatory CAFs, simulating the granulose-like reaction that includes production and secretion of cytokines, such as IL-8, IL-6, IL-1, CXCL12, and more, have also been described [77, 81, 167–169].

Investigators often seek to classify fibroblastic cell populations [92] as either anti-tumor, similar to local naïve fibroblastic cells such as pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), or pro-tumor, such as FAP expressing CAF [81, 101–103]. Yet, this binary characterization remains controversial [77, 79, 101–103, 170, 171]. Due to the dichotomy in pro- and anti-tumor functions as well as the various phenotypic and functional/mechanistic characteristics of CAFs, the notion of heterogeneous CAF populations has become an important focus for epithelial tumors that incorporate substantial stromal remodeling (i.e., desmoplasia) such as in breast, lung, and PDAC [82, 172–177]. Of note, despite being identified as distinct molecular signatures, differentially functional CAFs (such as myofibroblastic and inflammatory CAFs) describe fibroblastic cell functions (Figure 2) that are dynamically interchangeable [77, 81–83]. Then again, regardless of this functional heterogeneity, it seems that CAFs arise from anti-tumor fibroblastic (local or recruited) cell populations, for which cell lineages are only beginning to be traced [92, 169].

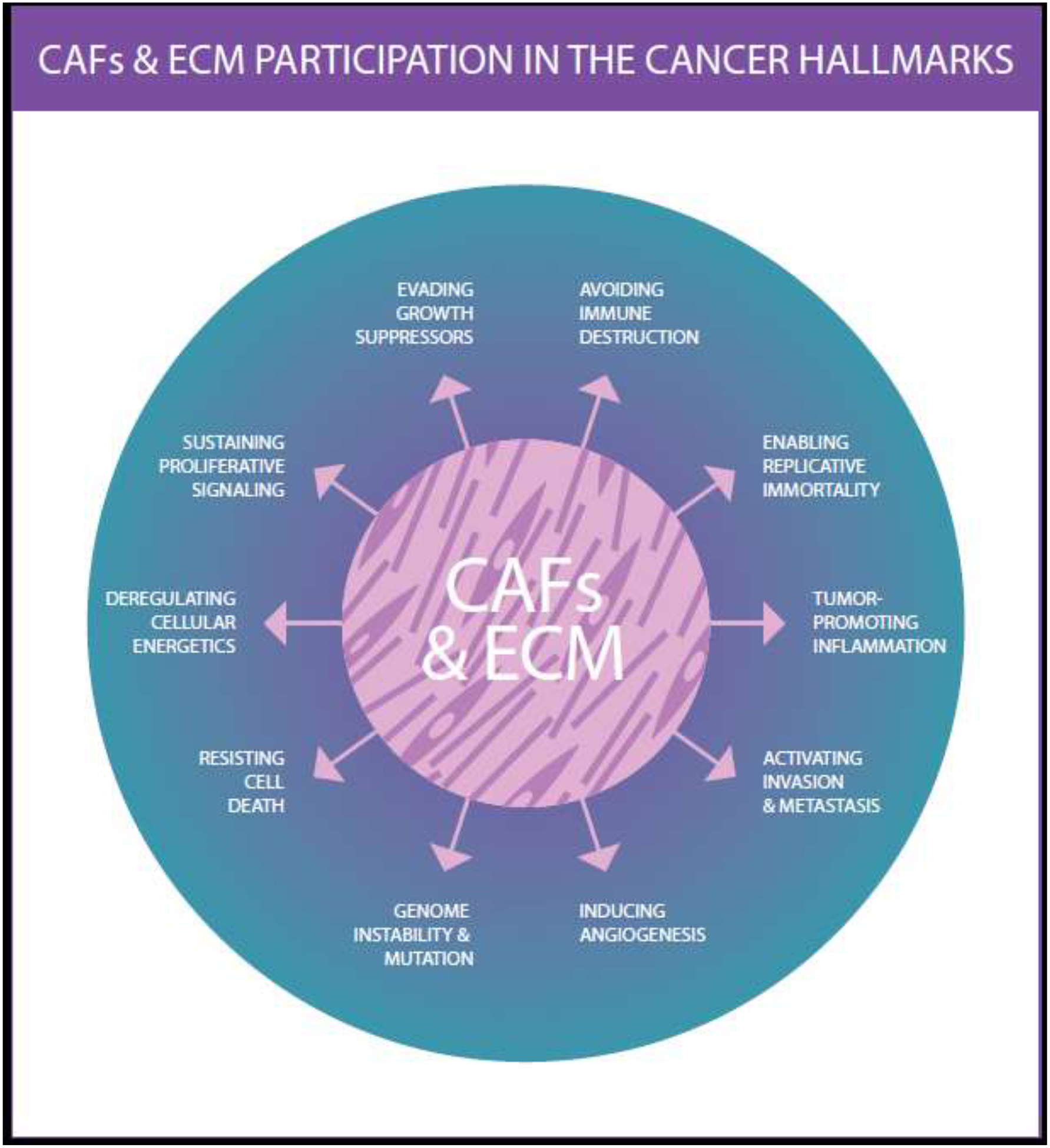

Hence, it is possible that the cytoskeletal dependent SDR, between fibroblastic cells and ECMs, is responsible for the local dynamic regulation of the CAF function that affect tumorigenesis (Figure 2), which encompass both the SMT and TOFT (Figure 1), and support all the recognized Hallmarks of Cancer (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Dynamic reciprocity between CAFs and ECM partakes in Cancer Hallmarks.

Illustration intended to highlight the fact that the dynamic reciprocity between CAFs and ECM results in the active regulation of all known Cancer Hallmarks. Note that this illustration was inspired by a figure displayed in Hanahan and Weinberg Cell 2011 [3]. Illustration by P. Ovseiovich, Mexico, DF.

Conclusion:

It is well understood that cancer is not uniform across patient cohorts. Instead, cancer is found to display tremendous heterogeneity, including both cancer and stromal cells, even within a single tumor. With this notion arose the Hallmarks of Cancer, to which treatments were designed to disrupt specific mechanisms that contributed to one or more trademark recognized to aid in tumor formation, growth, and progression (Figure 4). However, these therapeutic “magic bullets” have only proved to work transiently where resistance eventually evades the treatment and the disease continues to progress [178]. Thus, understanding and monitoring the long-term effects associated with targeting cancer hallmarks are crucial in effectively combating cancer progression as well as in preventing its development. Accordingly, a comprehensive understanding of SDR in general, and of the role of CAFs and ECM, may be key to establishing novel and more effective therapeutic efforts. From an evolutionarily standpoint, the body is physiologically conditioned to address and resolve insults that prompt temporary deviations from innate tissue functions through both local and systemic repair processes. These temporary occurrences are typically resolved whereby the acutely altered SDR is reverted to an innate homeostatic SDR equilibrium. It is plausible that this innate system is exploited during tumorigenesis thereby shifting the SDR balance towards a new equilibrium that supports tumorigenesis, such as desmoplastic SDR [78]. The desmoplastic SDR, between CAFs and ECM, then maintains the vicious cycle of tumorigenesis. While this pathological adaptation favors the aggressive nature of the disease state, ablation of compensatory elements in the SDR process impairs the possibility of restoring an innate tumor-restrictive stromal status. Thus, a thorough delineation of SDR mechanisms (i.e., amid CAFs and ECM), especially those that influence fibroblastic cell functions (Figure 2), may be vital to dissolving the regulatory features of cancer hallmarks (Figure 4), as well as consolidating SMT and TOFT (Figure 1), to eventually generate research that improves the development of effective and long lasting therapies.

Highlights:

When considering the stromal dynamic reciprocity between cancer associated fibroblasts and the extracellular matrix, two seemingly opposing cancer theories are mutually inclusive.

Stromal dynamic reciprocity is imperative to sustain cancer associated fibroblast functions during tumorigenesis.

Functions of cancer associated fibroblasts influence all known Cancer Hallmarks.

Acknowledgements:

This review is dedicated to the memory of the late P. Keely, who revolutionized the tumor microenvironment field. We apologize to all investigators whose studies were not included in this space restricted review. We would like to thank A Carson for proofreading. The group’s work is supported in part by gifts donated from the Marine DiNofrio Pancreatic Research Fund and by Jeanne Leinen. Also, by funds from the Martin and Concetta Greenberg Pancreatic cancer Institute, Pennsylvania’s DOH Health Research Formula Funds, and by the 5th AHEPA and Worldwide Cancer Research Foundations. This work was also supported by NIH/NCI grants R21-CA231252 and R01-CA232256, and by the Core grant CA06927 in support to Fox Chase Cancer Center’s facilities including: Bio Sample Repository, Microscopy, Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Cell Culture, Histopathology, Immune Monitoring, and the Talbot Library.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, Cancer statistics, 2020, CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 70(1) (2020) 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM, Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States, Cancer Res 74(11) (2014) 2913–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation, Cell 144(5) (2011) 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, The hallmarks of cancer, Cell 100(1) (2000) 57–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nikolaou M, Pavlopoulou A, Georgakilas AG, Kyrodimos E, The challenge of drug resistance in cancer treatment: a current overview, Clin Exp Metastasis 35(4) (2018) 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Tape Christopher J., Ling S, Dimitriadi M, McMahon Kelly M., Worboys Jonathan D., Leong Hui S., Norrie Ida C., Miller Crispin J., Poulogiannis G, Lauffenburger Douglas A., Jørgensen C, Oncogenic KRAS Regulates Tumor Cell Signaling via Stromal Reciprocation, Cell 165(4) (2016) 910–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Boveri T, Anton Dohbn, Science 36(928) (1912) 453–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Boveri T, Concerning the origin of malignant tumours by Theodor Boveri. Translated and annotated by Henry Harris, J Cell Sci 121 Suppl 1 (2008) 1–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barbacid M, Ortega S, Sotillo R, Odajima J, Martin A, Santamaria D, Dubus P, Malumbres M, Cell cycle and cancer: genetic analysis of the role of cyclin-dependent kinases, Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 70 (2005) 233–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Krontiris TG, Cooper GM, Transforming activity of human tumor DNAs, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78(2) (1981) 1181–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Prehn RT, Cancers beget mutations versus mutations beget cancers, Cancer Res 54(20) (1994) 5296–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Reddy EP, Reynolds RK, Santos E, Barbacid M, A point mutation is responsible for the acquisition of transforming properties by the T24 human bladder carcinoma oncogene, Nature 300(5888) (1982) 149–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Knudson AG Jr., Mutation and cancer: statistical study of retinoblastoma, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 68(4) (1971) 820–823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Harris H, A long view of fashions in cancer research, Bioessays 27(8) (2005) 833–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Rubin H, What keeps cells in tissues behaving normally in the face of myriad mutations?, Bioessays 28(5) (2006) 515–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Weinberg R, Mihich E, Eighteenth annual pezcoller symposium: tumor microenvironment and heterotypic interactions, Cancer Res 66(24) (2006) 11550–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kan Z, Jaiswal BS, Stinson J, Janakiraman V, Bhatt D, Stern HM, Yue P, Haverty PM, Bourgon R, Zheng J, Moorhead M, Chaudhuri S, Tomsho LP, Peters BA, Pujara K, Cordes S, Davis DP, Carlton VE, Yuan W, Li L, Wang W, Eigenbrot C, Kaminker JS, Eberhard DA, Waring P, Schuster SC, Modrusan Z, Zhang Z, Stokoe D, de Sauvage FJ, Faham M, Seshagiri S, Diverse somatic mutation patterns and pathway alterations in human cancers, Nature 466(7308) (2010) 869–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Imielinski M, Berger AH, Hammerman PS, Hernandez B, Pugh TJ, Hodis E, Cho J, Suh J, Capelletti M, Sivachenko A, Sougnez C, Auclair D, Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Cibulskis K, Choi K, de Waal L, Sharifnia T, Brooks A, Greulich H, Banerji S, Zander T, Seidel D, Leenders F, Ansen S, Ludwig C, Engel-Riedel W, Stoelben E, Wolf J, Goparju C, Thompson K, Winckler W, Kwiatkowski D, Johnson BE, Janne PA, Miller VA, Pao W, Travis WD, Pass HI, Gabriel SB, Lander ES, Thomas RK, Garraway LA, Getz G, Meyerson M, Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing, Cell 150(6) (2012) 1107–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lawrence MS, Stojanov P, Polak P, Kryukov GV, Cibulskis K, Sivachenko A, Carter SL, Stewart C, Mermel CH, Roberts SA, Kiezun A, Hammerman PS, McKenna A, Drier Y, Zou L, Ramos AH, Pugh TJ, Stransky N, Helman E, Kim J, Sougnez C, Ambrogio L, Nickerson E, Shefler E, Cortes ML, Auclair D, Saksena G, Voet D, Noble M, DiCara D, Lin P, Lichtenstein L, Heiman DI, Fennell T, Imielinski M, Hernandez B, Hodis E, Baca S, Dulak AM, Lohr J, Landau DA, Wu CJ, Melendez-Zajgla J, Hidalgo-Miranda A, Koren A, McCarroll SA, Mora J, Crompton B, Onofrio R, Parkin M, Winckler W, Ardlie K, Gabriel SB, Roberts CWM, Biegel JA, Stegmaier K, Bass AJ, Garraway LA, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Gordenin DA, Sunyaev S, Lander ES, Getz G, Mutational heterogeneity in cancer and the search for new cancer-associated genes, Nature 499(7457) (2013) 214–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Versteeg R, Cancer: Tumours outside the mutation box, Nature 506(7489) (2014) 438–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baker SG, A cancer theory kerfuffle can lead to new lines of research, J Natl Cancer Inst 107(2) (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Huggins C, Endocrine-induced regression of cancers, Cancer Res 27(11) (1967) 1925–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Haas D, Ablin AR, Miller C, Zoger S, Matthay KK, Complete pathologic maturation and regression of stage IVS neuroblastoma without treatment, Cancer 62(4) (1988) 818–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brodeur GM, Neuroblastoma: biological insights into a clinical enigma, Nat Rev Cancer 3(3) (2003) 203–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Illmensee K, Mintz B, Totipotency and normal differentiation of single teratocarcinoma cells cloned by injection into blastocysts, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 73(2) (1976) 549–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Sonnenschein C, Soto AM, Response to “In defense of the somatic mutation theory of cancer”. DOI: 10.1002/bies.201100022, Bioessays 33(9) (2011) 657–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Sonnenschein C, Soto AM, The death of the cancer cell, Cancer Res 71(13) (2011) 4334–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Soto AM, Sonnenschein C, The tissue organization field theory of cancer: a testable replacement for the somatic mutation theory, Bioessays 33(5) (2011) 332–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Peehl DM, Are primary cultures realistic models of prostate cancer?, J Cell Biochem 91(1) (2004) 185–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Montevil M, Speroni L, Sonnenschein C, Soto AM, Modeling mammary organogenesis from biological first principles: Cells and their physical constraints, Prog Biophys Mol Biol 122(1) (2016) 58–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Petersen OW, Ronnov-Jessen L, Howlett AR, Bissell MJ, Interaction with basement membrane serves to rapidly distinguish growth and differentiation pattern of normal and malignant human breast epithelial cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89(19) (1992) 9064–9068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Triolo VA, Nineteenth Century Foundations of Cancer Research. Origins of Experimental Research, Cancer Res 24 (1964) 4–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sonnenschein C, Soto AM, Theories of carcinogenesis: an emerging perspective, Semin Cancer Biol 18(5) (2008) 372–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Soto AM, Longo G, Montevil M, Sonnenschein C, The biological default state of cell proliferation with variation and motility, a fundamental principle for a theory of organisms, Prog Biophys Mol Biol 122(1) (2016) 16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Duda DG, Duyverman AM, Kohno M, Snuderl M, Steller EJ, Fukumura D, Jain RK, Malignant cells facilitate lung metastasis by bringing their own soil, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(50) (2010) 21677–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Barcellos-Hoff MH, Ravani SA, Irradiated mammary gland stroma promotes the expression of tumorigenic potential by unirradiated epithelial cells, Cancer Res 60(5) (2000) 1254–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Maffini MV, Soto AM, Calabro JM, Ucci AA, Sonnenschein C, The stroma as a crucial target in rat mammary gland carcinogenesis, J Cell Sci 117(8) (2004) 1495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xu R, Boudreau A, Bissell MJ, Tissue architecture and function: dynamic reciprocity via extra- and intra-cellular matrices, Cancer Metastasis Rev 28(1–2) (2009) 167–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Schultz GS, Davidson JM, Kirsner RS, Bornstein P, Herman IM, Dynamic reciprocity in the wound microenvironment, Wound Repair Regen 19(2) (2011) 134–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Thorne JT, Segal TR, Chang S, Jorge S, Segars JH, Leppert PC, Dynamic reciprocity between cells and their microenvironment in reproduction, Biol Reprod 92(1) (2015) 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Werb Z, Chin JR, Extracellular matrix remodeling during morphogenesis, Ann N Y Acad Sci 857 (1998) 110–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Nelson CM, Bissell MJ, Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer, Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 22 (2006) 287–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dvorak HF, Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing, N Engl J Med 315(26) (1986) 1650–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Rybinski B, Franco-Barraza J, Cukierman E, The wound healing, chronic fibrosis, and cancer progression triad, Physiological genomics 46(7) (2014) 223–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Rous P, An Experimental Comparison of Transplanted Tumor and a Transplanted Normal Tissue Capable of Growth, J Exp Med 12(3) (1910) 344–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tarin D, Clinical and Biological Implications of the Tumor Microenvironment, Cancer microenvironment : official journal of the International Cancer Microenvironment Society 5(2) (2012) 95–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Beacham DA, Cukierman E, Stromagenesis: the changing face of fibroblastic microenvironments during tumor progression, Semin Cancer Biol 15(5) (2005) 329–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Bhowmick NA, Neilson EG, Moses HL, Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression, Nature 432(7015) (2004) 332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Chu GC, Kimmelman AC, Hezel AF, DePinho RA, Stromal biology of pancreatic cancer, J Cell Biochem 101(4) (2007) 887–907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Kunz-Schughart LA, Knuechel R, Tumor-associated fibroblasts (Part I): active stromal participants in tumor development and progression?, Histol. Histopath 17(2) (2002) 599–621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hu M, Polyak K, Microenvironmental regulation of cancer development, Curr Opin Genet Dev 18(1) (2008) 27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Lakhani S, Bissell M, Introduction: the role of myoepithelial cells in integration of form and function in the mammary gland, J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 10(3) (2005) 197–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].de Jong KP, von Geusau BA, Rottier CA, Bijzet J, Limburg PC, de Vries EG, Fidler V, Slooff MJ, Serum response of hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-I, interleukin-6, and acute phase proteins in patients with colorectal liver metastases treated with partial hepatectomy or cryosurgery, J Hepatol 34(3) (2001) 422–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Mintz B, Illmensee K, Normal genetically mosaic mice produced from malignant teratocarcinoma cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 72(9) (1975) 3585–3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].McCullough KD, Coleman WB, Smith GJ, Grisham JW, Age-dependent induction of hepatic tumor regression by the tissue microenvironment after transplantation of neoplastically transformed rat liver epithelial cells into the liver, Cancer Res 57(9) (1997) 1807–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Booth BW, Boulanger CA, Anderson LH, Smith GH, The normal mammary microenvironment suppresses the tumorigenic phenotype of mouse mammary tumor virus-neu-transformed mammary tumor cells, Oncogene 30(6) (2011) 679–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ecker BL, Kaur A, Douglass SM, Webster MR, Almeida FV, Marino GE, Sinnamon AJ, Neuwirth MG, Alicea GM, Ndoye A, Fane M, Xu X, Sim MS, Deutsch GB, Faries MB, Karakousis GC, Weeraratna AT, Age-Related Changes in HAPLN1 Increase Lymphatic Permeability and Affect Routes of Melanoma Metastasis, Cancer Discov 9(1) (2019) 82–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Hotary KB, Allen ED, Brooks PC, Datta NS, Long MW, Weiss SJ, Membrane Type I Matrix Metalloproteinase Usurps Tumor Growth Control Imposed by the Three-Dimensional Extracellular Matrix, Cell 114(1) (2003) 33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Ellison ML, Ambrose EJ, Easty GC, Differentiation in a transplantable rat tumour maintained in organ culture, Exp Cell Res 55(2) (1969) 198–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Sherbet GV, Lakshmi MS, The surface properties of some human intracranial tumour cell lines in relation to their malignancy, Oncology 29(4) (1974) 335–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].DeCosse JJ, Gossens CL, Kuzma JF, Unsworth BR, Breast cancer: induction of differentiation by embryonic tissue, Science 181(4104) (1973) 1057–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Chung CJ, Cammoun D, Munden M, Rhabdoid tumor of the kidney presenting as an abdominal mass in a newborn, Pediatr Radiol 20(7) (1990) 562–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Wong YC, Cunha GR, Hayashi N, Effects of mesenchyme of the embryonic urogenital sinus and neonatal seminal vesicle on the cytodifferentiation of the Dunning tumor: ultrastructural study, Acta Anat (Basel) 143(2) (1992) 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Malik R, Luong T, Cao X, Han B, Shah N, Franco-Barraza J, Han L, Shenoy VB, Lelkes PI, Cukierman E, Rigidity controls human desmoplastic matrix anisotropy to enable pancreatic cancer cell spread via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2, Matrix Biol 81 (2019) 50–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Sakakura T, Nishizuka Y, Dawe CJ, Mesenchyme-dependent morphogenesis and epithelium-specific cytodifferentiation in mouse mammary gland, Science 194(4272) (1976) 1439–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Rubin H, ‘Spontaneous’ transformation as aberrant epigenesis, Differentiation 53(2) (1993) 123–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Foley JF, Aftonomos BT, Heidrick ML, Influence of fibroblastic collagen and mucopolysaccharides on HeLa cell colonial morphology, Life Sci 7(18) (1968) 1003–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM, Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension, Science 294(5547) (2001) 1708–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ingber DE, Tensegrity II. How structural networks influence cellular information processing networks, J Cell Sci 116(Pt 8) (2003) 1397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Yamamoto H, Itoh F, Adachi Y, Sakamoto H, Adachi M, Hinoda Y, Imai K, Relation of enhanced secretion of active matrix metalloproteinases with tumor spread in human hepatocellular carcinoma, Gastroenterology 112(4) (1997) 1290–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Mino N, Takenaka K, Sonobe M, Miyahara R, Yanagihara K, Otake Y, Wada H, Tanaka F, Expression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 (TIMP-3) and its prognostic significance in resected non-small cell lung cancer, J Surg Oncol 95(3) (2007) 250–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Thomasset N, Lochter A, Sympson CJ, Lund LR, Williams DR, Behrendtsen O, Werb Z, Bissell MJ, Expression of autoactivated stromelysin-1 in mammary glands of transgenic mice leads to a reactive stroma during early development, Am J Pathol 153(2) (1998) 457–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lochter A, Galosy S, Muschler J, Freedman N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ, Matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 triggers a cascade of molecular alterations that leads to stable epithelial-to-mesenchymal conversion and a premalignant phenotype in mammary epithelial cells, J Cell Biol 139(7) (1997) 1861–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Sternlicht MD, Lochter A, Sympson CJ, Huey B, Rougier JP, Gray JW, Pinkel D, Bissell MJ, Werb Z, The stromal proteinase MMP3/stromelysin-1 promotes mammary carcinogenesis, Cell 98(2) (1999) 137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Sternlicht MD, Bissell MJ, Werb Z, The matrix metalloproteinase stromelysin-1 acts as a natural mammary tumor promoter, Oncogene 19(8) (2000) 1102–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Tian C, Clauser KR, Ohlund D, Rickelt S, Huang Y, Gupta M, Mani DR, Carr SA, Tuveson DA, Hynes RO, Proteomic analyses of ECM during pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma progression reveal different contributions by tumor and stromal cells, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116(39) (2019) 19609–19618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, DeNardo DG, Egeblad M, Evans RM, Fearon D, Greten FR, Hingorani SR, Hunter T, Hynes RO, Jain RK, Janowitz T, Jorgensen C, Kimmelman AC, Kolonin MG, Maki RG, Powers RS, Pure E, Ramirez DC, Scherz-Shouval R, Sherman MH, Stewart S, Tlsty TD, Tuveson DA, Watt FM, Weaver V, Weeraratna AT, Werb Z, A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts, Nat Rev Cancer 20(3) (2020) 174–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Alexander J, Cukierman E, Stromal dynamic reciprocity in cancer: Intricacies of fibroblastic-ECM interactions, Curr Opin Cell Biol 42 (2016) 80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Neesse A, Bauer CA, Ohlund D, Lauth M, Buchholz M, Michl P, Tuveson DA, Gress TM, Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer: ready for clinical translation?, Gut 68(1) (2019) 159–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Zhang Y, Crawford HC, Pasca di Magliano M, Epithelial-Stromal Interactions in Pancreatic Cancer, Annu Rev Physiol 81 (2019) 211–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Öhlund D, Handly-Santana A, Biffi G, Elyada E, Almeida AS, Ponz-Sarvise M, Corbo V, Oni TE, Hearn SA, Lee EJ, Chio IIC, Hwang C-I, Tiriac H, Baker LA, Engle DD, Feig C, Kultti A, Egeblad M, Fearon DT, Crawford JM, Clevers H, Park Y, Tuveson DA, Distinct populations of inflammatory fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in pancreatic cancer, The Journal of Experimental Medicine 214(3) (2017) 579–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Elyada E, Bolisetty M, Laise P, Flynn WF, Courtois ET, Burkhart RA, Teinor JA, Belleau P, Biffi G, Lucito MS, Sivajothi S, Armstrong TD, Engle DD, Yu KH, Hao Y, Wolfgang CL, Park Y, Preall J, Jaffee EM, Califano A, Robson P, Tuveson DA, Cross-species single-cell analysis of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma reveals antigen-presenting cancer-associated fibroblasts, Cancer Discov (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Biffi G, Oni TE, Spielman B, Hao Y, Elyada E, Park Y, Preall J, Tuveson DA, IL-1-induced JAK/STAT signaling is antagonized by TGF-beta to shape CAF heterogeneity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Cancer Discov 9(2) (2019) 282–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Franco-Barraza J, Francescone R, Luong T, Shah N, Madhani R, Cukierman G, Dulaimi E, Devarajan K, Egleston BL, Nicolas E, Alpaugh KR, Malik R, Uzzo RG, Hoffman JP, Golemis EA, Cukierman E, Matrix-regulated integrin αvβ5 maintains α5β1-dependent desmoplastic traits prognostic of neoplastic recurrence, eLife 6 (2017) e20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Basturk O, Hong SM, Wood LD, Adsay NV, Albores-Saavedra J, Biankin AV, Brosens LA, Fukushima N, Goggins M, Hruban RH, Kato Y, Klimstra DS, Kloppel G, Krasinskas A, Longnecker DS, Matthaei H, Offerhaus GJ, Shimizu M, Takaori K, Terris B, Yachida S, Esposito I, Furukawa T, A Revised Classification System and Recommendations From the Baltimore Consensus Meeting for Neoplastic Precursor Lesions in the Pancreas, The American journal of surgical pathology 39(12) (2015) 1730–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].von Ahrens D, Bhagat TD, Nagrath D, Maitra A, Verma A, The role of stromal cancer-associated fibroblasts in pancreatic cancer, Journal of hematology & oncology 10(1) (2017) 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Bernard V, Semaan A, Huang J, San Lucas FA, Mulu FC, Stephens BM, Guerrero PA, Huang Y, Zhao J, Kamyabi N, Sen S, Scheet PA, Taniguchi CM, Kim MP, Tzeng CW, Katz MH, Singhi AD, Maitra A, Alvarez HA, Single-Cell Transcriptomics of Pancreatic Cancer Precursors Demonstrates Epithelial and Microenvironmental Heterogeneity as an Early Event in Neoplastic Progression, Clin Cancer Res 25(7) (2019) 2194–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, Maitra A, Bailey JM, McAllister F, Reichert M, Beatty GL, Rustgi AK, Vonderheide RH, Leach SD, Stanger BZ, EMT and Dissemination Precede Pancreatic Tumor Formation, Cell 148(1–2) (2012) 349–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Giovannetti E, van der Borden CL, Frampton AE, Ali A, Firuzi O, Peters GJ, Never let it go: Stopping key mechanisms underlying metastasis to fight pancreatic cancer, Semin Cancer Biol 44 (2017) 43–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Provenzano Paolo P., Cuevas C, Chang Amy E., Goel Vikas K., Von Hoff Daniel D., Hingorani Sunil R., Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Cancer cell 21(3) (2012) 418–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Morrison AH, Byrne KT, Vonderheide RH, Immunotherapy and Prevention of Pancreatic Cancer, Trends Cancer 4(6) (2018) 418–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Puleo F, Nicolle R, Blum Y, Cros J, Marisa L, Demetter P, Quertinmont E, Svrcek M, Elarouci N, Iovanna J, Franchimont D, Verset L, Galdon MG, Deviere J, de Reynies A, Laurent-Puig P, Van Laethem JL, Bachet JB, Marechal R, Stratification of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinomas Based on Tumor and Microenvironment Features, Gastroenterology 155(6) (2018) 1999–2013.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Lyssiotis CA, Kimmelman AC, Metabolic Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment, Trends in Cell Biology (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Pandol S, Edderkaoui M, Gukovsky I, Lugea A, Gukovskaya A, Desmoplasia of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 7(11 Suppl) (2009) S44–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Rasheed ZA, Matsui W, Maitra A, Pathology of pancreatic stroma in PDAC, in: Grippo PJ, Munshi HG (Eds.), Pancreatic Cancer and Tumor Microenvironment, Trivandrum (India), 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Ziani L, Chouaib S, Thiery J, Alteration of the Antitumor Immune Response by Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts, Frontiers in immunology 9 (2018) 414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Ligorio M, Sil S, Malagon-Lopez J, Nieman LT, Misale S, Di Pilato M, Ebright RY, Karabacak MN, Kulkarni AS, Liu A, Vincent Jordan N, Franses JW, Philipp J, Kreuzer J, Desai N, Arora KS, Rajurkar M, Horwitz E, Neyaz A, Tai E, Magnus NKC, Vo KD, Yashaswini CN, Marangoni F, Boukhali M, Fatherree JP, Damon LJ, Xega K, Desai R, Choz M, Bersani F, Langenbucher A, Thapar V, Morris R, Wellner UF, Schilling O, Lawrence MS, Liss AS, Rivera MN, Deshpande V, Benes CH, Maheswaran S, Haber DA, Fernandez-Del-Castillo C, Ferrone CR, Haas W, Aryee MJ, Ting DT, Stromal Microenvironment Shapes the Intratumoral Architecture of Pancreatic Cancer, Cell 178(1) (2019) 160–175.e27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Hwang RF, Moore T, Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Amos KD, Rivera A, Ji B, Evans DB, Logsdon CD, Cancer-Associated Stromal Fibroblasts Promote Pancreatic Tumor Progression, Cancer Res 68(3) (2008) 918–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Bachem MG, Schunemann M, Ramadani M, Siech M, Beger H, Buck A, Zhou S, Schmid-Kotsas A, Adler G, Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells, Gastroenterology 128(4) (2005) 907–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Erkan M, Michalski CW, Rieder S, Reiser-Erkan C, Abiatari I, Kolb A, Giese NA, Esposito I, Friess H, Kleeff J, The Activated Stroma Index Is a Novel and Independent Prognostic Marker in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 6(10) (2008) 1155–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Lo A, Wang LC, Scholler J, Monslow J, Avery D, Newick K, O’Brien S, Evans RA, Bajor DL, Clendenin C, Durham AC, Buza EL, Vonderheide RH, June CH, Albelda SM, Pure E, Tumor-promoting desmoplasia is disrupted by depleting FAP-expressing stromal cells, Cancer Res 75(14) (2015) 2800–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Rhim Andrew D., Oberstein Paul E., Thomas Dafydd H., Mirek Emily T., Palermo Carmine F., Sastra Stephen A., Dekleva Erin N., Saunders T, Becerra Claudia P., Tattersall Ian W., Westphalen CB, Kitajewski J, Fernandez-Barrena Maite G., Fernandez-Zapico Martin E., Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Olive Kenneth P., Stanger Ben Z., Stromal Elements Act to Restrain, Rather Than Support, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, Cancer cell 25(6) (2014) 735–747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Özdemir Berna C., Pentcheva-Hoang T, Carstens Julienne L., Zheng X, Wu C-C, Simpson Tyler R., Laklai H, Sugimoto H, Kahlert C, Novitskiy Sergey V., De Jesus-Acosta A, Sharma P, Heidari P, Mahmood U, Chin L, Moses Harold L., Weaver Valerie M., Maitra A, Allison James P., LeBleu Valerie S., Kalluri R, Depletion of Carcinoma-Associated Fibroblasts and Fibrosis Induces Immunosuppression and Accelerates Pancreas Cancer with Reduced Survival, Cancer cell 25(6) (2014) 719–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Amatangelo MD, Bassi DE, Klein-Szanto AJ, Cukierman E, Stroma-derived three-dimensional matrices are necessary and sufficient to promote desmoplastic differentiation of normal fibroblasts, Am J Pathol 167(2) (2005) 475–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Avery D, Govindaraju P, Jacob M, Todd L, Monslow J, Pure E, Extracellular matrix directs phenotypic heterogeneity of activated fibroblasts, Matrix Biol 67 (2018) 90–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Munger JS, Sheppard D, Cross talk among TGF-beta signaling pathways, integrins, and the extracellular matrix, Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 3(11) (2011) a005017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Kuwahara K, Kinoshita H, Kuwabara Y, Nakagawa Y, Usami S, Minami T, Yamada Y, Fujiwara M, Nakao K, Myocardin-related transcription factor A is a common mediator of mechanical stress- and neurohumoral stimulation-induced cardiac hypertrophic signaling leading to activation of brain natriuretic peptide gene expression, Mol Cell Biol 30(17) (2010) 4134–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Hinz B, Celetta G, Tomasek JJ, Gabbiani G, Chaponnier C, Alpha-smooth muscle actin expression upregulates fibroblast contractile activity, Mol Biol Cell 12(9) (2001) 2730–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, Inman DR, White JG, Keely PJ, Collagen reorganization at the tumor-stromal interface facilitates local invasion, BMC Med 4(1) (2006) 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Prunotto M, Desmouliere A, Varga J, De Wever O, Mareel M, Gabbiani G, Recent developments in myofibroblast biology: paradigms for connective tissue remodeling, Am J Pathol 180(4) (2012) 1340–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Crider BJ, Risinger GM Jr., Haaksma CJ, Howard EW, Tomasek JJ, Myocardin-related transcription factors A and B are key regulators of TGF-beta1-induced fibroblast to myofibroblast differentiation, The Journal of investigative dermatology 131(12) (2011) 2378–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Wipff P-J, Rifkin DB, Meister J-J, Hinz B, Myofibroblast contraction activates latent TGF-beta1 from the extracellular matrix, J. Cell Biol 179(6) (2007) 1311–1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Otranto M, Sarrazy V, Bonté F, Hinz B, Gabbiani G, Desmouliere A, The role of the myofibroblast in tumor stroma remodeling, Cell adhesion & migration 6(3) (2012) epub ahead of time. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Neesse A, Michl P, Frese KK, Feig C, Cook N, Jacobetz MA, Lolkema MP, Buchholz M, Olive KP, Gress TM, Tuveson DA, Stromal biology and therapy in pancreatic cancer, Gut 60(6) (2011) 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Mitchison TJ, Evolution of a dynamic cytoskeleton, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 349(1329) (1995) 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Iozzo RV, Gubbiotti MA, Extracellular matrix: The driving force of mammalian diseases, Matrix Biol 71–72 (2018) 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Erickson HP, Evolution of the cytoskeleton, Bioessays 29(7) (2007) 668–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Jaeken L, A new list of functions of the cytoskeleton, IUBMB Life 59(3) (2007) 127–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Atema J, Microtube theory of sensory transduction, J Theor Biol 38(1) (1973) 181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Puck TT, Krystosek A, Role of the cytoskeleton in genome regulation and cancer, Int Rev Cytol 132 (1992) 75–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Foster CR, Robson JL, Simon WJ, Twigg J, Cruikshank D, Wilson RG, Hutchison CJ, The role of Lamin A in cytoskeleton organization in colorectal cancer cells: a proteomic investigation, Nucleus 2(5) (2011) 434–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Sun BO, Fang Y, Li Z, Chen Z, Xiang J, Role of cellular cytoskeleton in epithelial-mesenchymal transition process during cancer progression, Biomed Rep 3(5) (2015) 603–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Willis ND, Cox TR, Rahman-Casans SF, Smits K, Przyborski SA, van den Brandt P, van Engeland M, Weijenberg M, Wilson RG, de Bruine A, Hutchison CJ, Lamin A/C is a risk biomarker in colorectal cancer, PLoS One 3(8) (2008) e2988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Skvortsov S, Schafer G, Stasyk T, Fuchsberger C, Bonn GK, Bartsch G, Klocker H, Huber LA, Proteomics profiling of microdissected low- and high-grade prostate tumors identifies Lamin A as a discriminatory biomarker, J Proteome Res 10(1) (2011) 259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Wu Z, Wu L, Weng D, Xu D, Geng J, Zhao F, Reduced expression of lamin A/C correlates with poor histological differentiation and prognosis in primary gastric carcinoma, J Exp Clin Cancer Res 28 (2009) 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Gong G, Chen P, Li L, Tan H, Zhou J, Zhou Y, Yang X, Wu X, Loss of lamin A but not lamin C expression in epithelial ovarian cancer cells is associated with metastasis and poor prognosis, Pathol Res Pract 211(2) (2015) 175–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Yang X, Lin Y, Functions of nuclear actin-binding proteins in human cancer, Oncol Lett 15(3) (2018) 2743–2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Gupta V, Bassi DE, Simons JD, Devarajan K, Al-Saleem T, Uzzo RG, Cukierman E, Elevated expression of stromal palladin predicts poor clinical outcome in renal cell carcinoma, PLoS ONE 6(6) (2011) e21494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Cannon AR, Owen MK, Guerrero MS, Kerber ML, Goicoechea SM, Hemstreet KC, Klazynski B, Hollyfield J, Chang EH, Hwang RF, Otey CA, Kim HJ, Palladin expression is a conserved characteristic of the desmoplastic tumor microenvironment and contributes to altered gene expression, Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 72(8) (2015) 402–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Goicoechea SM, Bednarski B, Stack C, Cowan DW, Volmar K, Thorne L, Cukierman E, Rustgi AK, Brentnall T, Hwang RF, McCulloch CA, Yeh JJ, Bentrem DJ, Hochwald SN, Hingorani SR, Kim HJ, Otey CA, Isoform-specific upregulation of palladin in human and murine pancreas tumors, PLoS One 5(4) (2010) e10347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Salaria SN, Illei P, Sharma R, Walter KM, Klein AP, Eshleman JR, Maitra A, Schulick R, Winter J, Ouellette MM, Goggins M, Hruban R, Palladin is overexpressed in the non-neoplastic stroma of infiltrating ductal adenocarcinomas of the pancreas, but is only rarely overexpressed in neoplastic cells, Cancer Biol Ther 6(3) (2007) 324–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Sato D, Tsuchikawa T, Mitsuhashi T, Hatanaka Y, Marukawa K, Morooka A, Nakamura T, Shichinohe T, Matsuno Y, Hirano S, Stromal Palladin Expression Is an Independent Prognostic Factor in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma, PLoS One 11(3) (2016) e0152523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Goicoechea SM, Bednarski B, Garcia-Mata R, Prentice-Dunn H, Kim HJ, Otey CA, Palladin contributes to invasive motility in human breast cancer cells, Oncogene 28(4) (2009) 587–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Goicoechea SM, Prentice-Dunn H, Bednarski B, Ding XY, Kim HJ, Otey CA, Palladin expression contributes to invasive motility in metastatic breast cancer cells, Clin Exp Metastas 26(7) (2009) 850–851. [Google Scholar]

- [135].Bednarski BK, Goicoechea S, Otey C, Kim HJ, Characterization of Palladin and Its Isoforms in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma, Ann Surg Oncol 16 (2009) 39–40. [Google Scholar]

- [136].Asparuhova MB, Gelman L, Chiquet M, Role of the actin cytoskeleton in tuning cellular responses to external mechanical stress, Scand J Med Sci Sports 19(4) (2009) 490–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Huang X, Yang N, Fiore VF, Barker TH, Sun Y, Morris SW, Ding Q, Thannickal VJ, Zhou Y, Matrix stiffness-induced myofibroblast differentiation is mediated by intrinsic mechanotransduction, American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 47(3) (2012) 340–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Bissell MJ, Hines WC, Why don’t we get more cancer? A proposed role of the microenvironment in restraining cancer progression, Nat Med 17(3) (2011) 320–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Geiger B, Bershadsky A, Pankov R, Yamada KM, Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix--cytoskeleton crosstalk, Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2(11) (2001) 793–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Tseng Y, Kole TP, Lee JS, Fedorov E, Almo SC, Schafer BW, Wirtz D, How actin crosslinking and bundling proteins cooperate to generate an enhanced cell mechanical response, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 334(1) (2005) 183–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Lee HW, Park YM, Lee SJ, Cho HJ, Kim DH, Lee JI, Kang MS, Seol HJ, Shim YM, Nam DH, Kim HH, Joo KM, Alpha-smooth muscle actin (ACTA2) is required for metastatic potential of human lung adenocarcinoma, Clin Cancer Res 19(21) (2013) 5879–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Nanda S, Pancreas: high stromal expression of alpha-smooth-muscle actin correlates with aggressive pancreatic cancer biology, Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 7(12) (2010) 652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Gerashchenko GV, Grygoruk OV, Kononenko OA, Gryzodub OP, Stakhovsky EO, Kashuba VI, Expression pattern of genes associated with tumor microenvironment in prostate cancer, Exp Oncol 40(4) (2018) 315–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Kim S, You D, Jeong Y, Yu J, Kim SW, Nam SJ, Lee JE, TP53 upregulates alphasmooth muscle actin expression in tamoxifenresistant breast cancer cells, Oncol Rep 41(2) (2019) 1075–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Stevenson RP, Veltman D, Machesky LM, Actin-bundling proteins in cancer progression at a glance, J Cell Sci 125(Pt 5) (2012) 1073–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Perrin BJ, Ervasti JM, The actin gene family: function follows isoform, Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 67(10) (2010) 630–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Percipalle P, The long journey of actin and actin-associated proteins from genes to polysomes, Cell Mol Life Sci 66(13) (2009) 2151–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Tsukamoto H, Mishima Y, Hayashibe K, Sasase A, Alpha-smooth muscle actin expression in tumor and stromal cells of benign and malignant human pigment cell tumors, J Invest Dermatol 98(1) (1992) 116–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Drifka CR, Loeffler AG, Esquibel CR, Weber SM, Eliceiri KW, Kao WJ, Human pancreatic stellate cells modulate 3D collagen alignment to promote the migration of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells, Biomedical microdevices 18(6) (2016) 105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Drifka CR, Loeffler AG, Mathewson K, Keikhosravi A, Eickhoff JC, Liu Y, Weber SM, Kao WJ, Eliceiri KW, Highly aligned stromal collagen is a negative prognostic factor following pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma resection, Oncotarget 7(46) (2016) 76197–76213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Drifka CR, Tod J, Loeffler AG, Liu Y, Thomas GJ, Eliceiri KW, Kao WJ, Periductal stromal collagen topology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma differs from that of normal and chronic pancreatitis, Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc 28(11) (2015) 1470–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]