Abstract

Small RNA molecules in early embryos delivered from sperm to zygotes upon fertilization are required for normal mouse embryonic development and even modest changes in the levels of sperm-derived miRNAs appear to influence early embryos and subsequent development. For example, stress-associated behaviors develop in mice after injection into normal zygotes sets of sperm miRNAs elevated in stressed male mice. Here, we implicate early embryonic miR-409–3p in establishing anxiety levels in adult female, but not male mice. First, we found that exposure of male mice to chronic social instability stress, which leads to elevated anxiety in their female offspring across at least three generations through the paternal lineage, elevates sperm miR-409–3p levels not only in exposed males but also in sperm of their F1 and F2 male offspring. Second, we observed that while injection of a mimic of miR-409–3p into zygotes from mating control males was incapable of mimicking this effect in offspring derived from them, injection of a specific inhibitor of this miRNA led to the opposite anxiolytic effect in female, but not male offspring. These findings imply that baseline miR-409–3p activity in early female embryos is necessary for the expression of normal anxiety levels when they develop into adult females. In addition, elevated embryo miR-409–3p activity, possibly as a consequence of stress-induced elevation of its expression in sperm, may participate in, but may not be sufficient for, the induction of enhanced anxiety.

Keywords: miRNAs, anxiety, preimplantation embryos, epigenetics

Background

It has long been assumed that sperm’s only contribution to the development of zygotes upon fertilization is paternal DNA. However, a growing body of evidence supports the idea that small RNA molecules including miRNA, piRNAs, siRNAs, and tRNA fragments present in sperm are delivered to zygotes upon conception and also contribute to embryo development (Reza et al., 2019). For example, conditional knockout (cKO) mice that lack the ability to process siRNA and miRNAs in sperm produce zygotes with reduced developmental potential. miRNA content changes observed during the earliest stages of development suggest that they might be key regulatory players during the developmental transition from the fertilized zygote to pluripotent blastocyst (Reza et al., 2019).

One of the most studied examples of how sperm miRNA delivery to zygotes influences development is how the effects of stress on male mice are transmitted across generations. Male stressors that produce transgenerational effects include social defeat (Dietz et al., 2011), chronic physical restraint (He et al., 2016), multiple variable stressors (Rodgers, Morgan, Bronson, Revello, & Bale, 2013) early maternal separation (Franklin et al., 2010), and chronic social instability (CSI)(Dickson et al., 2018; Saavedra-Rodriguez & Feig, 2013). Two sets of reports in mice clearly implicate stress-induced increases in the levels of specific sets of sperm miRNAs in transmitting traits across generations. In one study (Gapp et al., 2014) early maternal separation of males from stressed mothers leads to increased expression of a variety of sperm miRNAs in adult males, and depression and sociability impairments in their future male and female offspring. Injection of total sperm RNA from stressed fathers into zygotes mimics some of these effects when these animals mature. In the other (Rodgers, Morgan, Leu, & Bale, 2015), chronic variable stress in adulthood suppresses the HPA axis response in offspring and leads to increased expression of 9 sperm miRNAs. Injection of all of them into zygotes leads to similar phenotypes when they mature. Our recent study on social instability stress in male mice implicated reductions in the levels of members of the sperm miRNA 34/449 family in transmitting increased anxiety and reduced sociability specifically in female offspring across multiple generations (Dickson et al., 2018). A striking aspect of this series of studies, yet to be addressed, is that different stress paradigms produce different effects in offspring through different sperm miRNA changes. They range from enhanced anxiety and depression to blunted HPA axis response, and from female or male specific to no sex specificity in offspring. Although changes in early embryo gene expression patterns have been identified in offspring of stressed fathers, how individual miRNAs contribute to both the modification of stress phenotypes and the sex dependence of the phenomenon remains obscure.

In this study we investigate the role of miR-409–3p in early embryos in the context of stress phenotypes induced across multiple generations by social instability stress. The results imply that baseline levels of miR-409–3p in female, but not male, early embryos contribute to anxiety-associated behaviors when they mature to adults. However, elevating levels of this miRNA in early embryos in and of itself is not sufficient to enhance anxiety in adult females.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Care Facilities

All mice included in this study are of the CD-1 strain, obtained from Charles River Laboratories. All animals are housed in temperature, humidity, and light-controlled (14 hour on/10 hour off LD cycle) rooms in a fully staffed dedicated animal core facility led by on-call veterinarians at all hours. Food and water were provided ad libitum. All procedures and protocols involving these mice were conducted in accordance with and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston MA and the Maine Medical Center Research Institute, Scarborough ME.

Chronic Social Instability (CSI) stress

Male “F0” juvenile CD-1 mice arrived at P21 and were given a week to acclimate to our mouse facilities. Starting at P28, the composition of each mouse cage (4 mice per cage) was randomly shuffled twice per week, for seven weeks, such that each mouse was housed with 3 new mice in a fresh, clean cage at each change (Sterlemann et al., 2008). This shuffling was randomized to reduce the chance that any mouse would encounter the same mouse twice. Control mice were housed four mice per cage with the same cage mates for the duration of the protocol. After seven weeks, mice were housed in pairs with a cage mate from the final cage change and left for two weeks to remove acute effects of the final change. Male mice (both control and stressed) were then “tease” mated with a naive female mouse for 2 days to increase sperm production. Mice were then either sacrificed for sperm collection or mated with control female mice overnight to generate “F1” animals, with successful mating confirmed via presence of copulation plug the following morning. We have previously shown that stressed males can be mated multiple times and still transmit stress phenotypes to their offspring, so male mice were used for mating, embryo collection, or sperm collection as needed.

Mouse Sperm Collection

Mature, motile mouse sperm was isolated via the swim-up method. Briefly, male mice were anesthetized under isoflurane and sacrificed via rapid decapitation. The caudal epididymis and vas deferens were dissected bilaterally and placed in 1 mL of warm (37˚C) M16 medium (Sigma-Aldrich, SKU# MR-016-D) in a small petri dish. Under a dissection microscope, sperm were manually expressed from the vas deferens using fine forceps, and the epididymis was cut several times before incubating at 37˚C for 15 minutes to allow mature sperm to swim out, then large pieces of tissue were removed. The remainder of the extraction took place in a 37˚C warm room. The sperm-containing media was centrifuged at 3000 RPM for 8 minutes, supernatant was withdrawn and discarded, and 400 uL of fresh, warm M16 medium was then carefully placed on top of the pellet. The tubes were then allowed to rest at a 45˚ angle for 45 minutes to allow the motile sperm to swim-up out of the pellet into the fresh medium. The supernatant containing the mature sperm was then carefully withdrawn and several tubes worth (n=4–6 mice) were combined (in order to reach sufficient quantities of RNA) and centrifuged again for 8 minutes at 3000 RPM to pellet the motile sperm. Supernatant was withdrawn and discarded, and the pellet was frozen on dry ice for later processing.

Zygote microinjection and reimplantation

To obtain sufficient numbers of embryos, a superovulation protocol was employed. Control adult (8 weeks) female mice were injected with 7.5 U of pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMS, National Hormone & Pituitary Program, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center) and 46 h later injected with 7.5 U of human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG, Sigma-Aldrich, SKU# C1063) and placed into the home cage of the male to mate overnight. In the morning, female mice were checked for copulation plugs and returned to their own cages. If 2-cell and 4-cell embryos were desired, female mice were sacrificed about 1.5 days later, and for 8-cell/morula they were sacrificed about 2 days later. On the day of collection, mice were sacrificed via cervical dislocation. Under a dissection microscope, the uterus was removed and a very high-gauge needle was inserted into the opening of the fallopian tubes and the embryos were flushed out using warm 37 °C EmbryoMax FHM HEPES-buffered medium (1×) w/o Phenol Red (EMD Millipore, SKU# MR-122-D). The embryos were separated according to cell number, and any unfertilized ova or embryos displaying unusual morphology were discarded. The embryos of interest were pooled by cell stage, and snap frozen on dry ice. Each specific cell-stage sample represents embryos derived from the mating of at least three distinct breeding pairs of mice. Typically, three–four super-ovulated females were mated with three–four males (either F0 control, or F0 stress) for each experiment in order to generate enough embryos needed for a single pool (30–60 embryos total) of a specific cell-stage embryo (2-cell, 4-cell, etc.) to recover sufficient quantities of RNA for downstream analysis. Microinjection experiments were carried out according to standard techniques. Briefly, control zygotes were isolated as described above from female mice the afternoon following mating. 1–2 pL of either miR-409–3p mimic (Exiqon North America), its associated negative control (Exiqon North America), or the miR-409–3p inhibitor (Exiqon North America), or its negative control were injected at 2ng/uL in injection buffer (10 mM Tris-HCL,pH 7.4, 0.25 mM EDTA) into the zygote under a high-powered light microscope. Following injection, embryos were cultured for 48 hours until reaching the 4-cell stage where they were frozen at −80C.

Mouse Behavioral Assays

All mice were tested at 2 months of age for all behavioral tests. All mice were habituated to the testing room for at least 1 hour prior to beginning testing. All experiments were performed from 1:00PM – 4:00PM, during the light cycle. For the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM), animals were placed into the center neutral square of the apparatus, and then allowed to roam freely for 5 minutes. Speed and position were collected using Anymaze (Stoelting) video capture tracking and analyzed for total time spent in the open arms. For the Social Interaction with a Juvenile (SIJ) assay, mice were placed in a fresh, clean cage for 15 minutes to habituate to the new enclosure. A juvenile, same-sex mouse (age P21-P28) was then placed in the cage for 3 minutes. Videos were then scored, in a blinded fashion, for the amount of time that the experimental mouse spent performing affiliative behaviors on the juvenile mouse (grooming, sniffing, direct contact, etc.). Aggressive behavior was not included in this category. Excessive aggressive behavior was considered sufficient cause to end the behavioral assessment and remove the animals back to their own cages.

RNA extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse sperm samples using the miRVana miRNA Isolation Kit (Invitrogen, # AM1561) according to the manufacturers protocol. Total RNA was extracted from mouse embryos using the Norgen Single-Cell RNA Isolation kit (Norgen Biotek Corp., #51800) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Concentration of RNA was determined using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Genomics) and NanoDrop-1000 (Thermofisher Scientific). Relative miRNA expression for sperm and embryo samples was determined using the Taqman MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit and qPCR system (Applied Biosystems, # 4366596) purchased from Thermofisher Scientific. 10 ng of total RNA from sperm, and 1 ng of total RNA from embryos, were used in the initial cDNA synthesis kit. Real-Time PCR was performed for each target and sample in triplicate on a StepOnePlus PCR System (Applied Biosystems). All data was analyzed using the Comparative ΔΔCT method to generate relative expression data using the small noncoding RNA sno202 as the internal control for all samples with this kit.

Statistics

For all calculations, a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. All figures and statistical analyses were performed in Graphpad Prism v7.0 unless otherwise stated. Comparison of miR-409–3p expression in mouse sperm presented as mean+/− standard error for pooled samples. Data for miR-409–3p expression in 4-cell embryos is expressed as fold change ± experimental error as each bar represents an individual extraction of 30–60 embryos derived from at least 3 female mice that were pooled before analysis (see collection procedure above). EPM and SIJ behavioral assays were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA (Main effects: 409–3p manipulation, sex), with posthoc analyses corrected for multiple comparisons using the Sidak method. EPM results from stressed male embryo injection analyzed using 1-way ANOVA.

Results

Chronic social instability stress elevates levels of sperm miR-409–3p across three generations

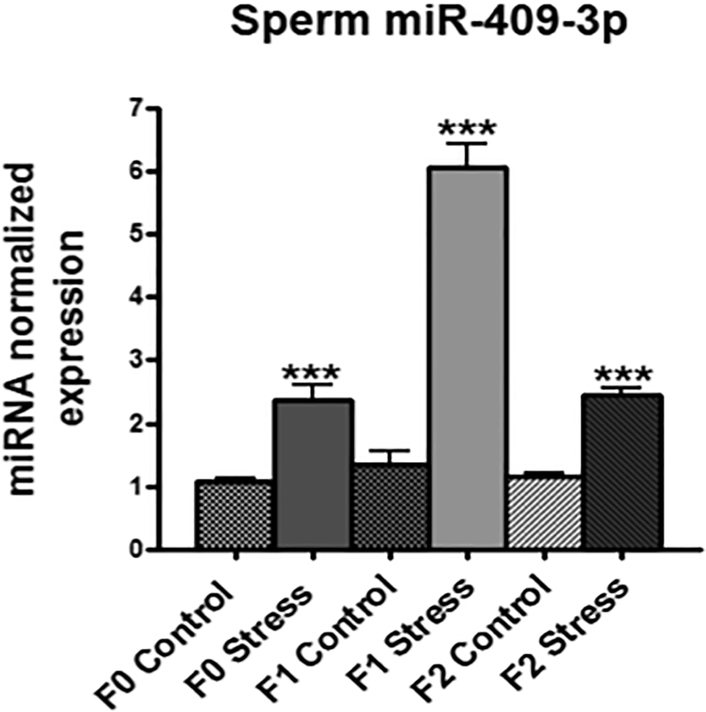

We previously published that exposure of adolescent male mice to 7 weeks of chronic social instability (CSI) stress leads to elevated anxiety and defective social interactions in their female, but not male, offspring across at least three generations (Saavedra-Rodriguez & Feig, 2013). We have recently implicated stress-induced reductions in sperm miRs-34c and 449a in this process (Dickson et al., 2018). Because other stress paradigms have implicated sperm miRNAs whose expressions rise in this process, we performed microarray analysis comparing the expression of sperm miRNAs in control and stressed males. We searched for sperm miRNAs whose levels are elevated not only in sperm from stressed males but also in their F1 and F2 male offspring. Among hundreds of miRNAs analyzed, only miR-409–3p fit these criteria, where its expression was elevated (~2–6 fold) in sperm across three generations of males derived from CSI stress exposed male mice (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Sperm miR-409–3p levels are increased following CSI stress across three generations of the male lineage.

qPCR analysis of miR-409–3p expression for 2 groups each of sperm RNA pooled from 4–6 male mice from F0 (original stressed males), F1 (sons of F0 stressed males), and F2 (grandsons of F0 stressed males) generations. Data normalized to expression for control group for each individual generation. Analysis by 2-way ANOVA identified a significant effect due to stress across all three generations (P=0.0039).

Injection of an inhibitor to miR-409–3p into zygotes generates reduced anxiety in female, but not male, offspring

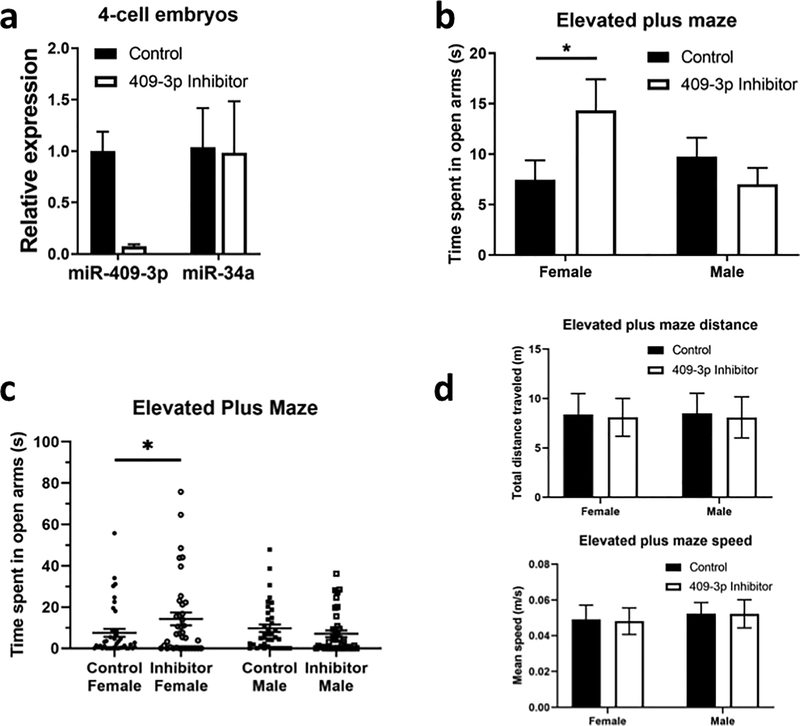

In order to determine whether increased delivery of sperm miR-409–3p to the zygote at fertilization is necessary and/or sufficient to enhance anxiety and/or sociability defects in female offspring, we manipulated its levels in early embryos. Proving it is necessary is less stringent. Thus, we began by injecting zygotes from the mating of control animals with a miR-409–3p inhibitor (or a negative control inhibitor) to reveal how early inhibition of miR-409–3p affects behavior when zygotes develop into adults. Thus, injected zygotes were re-implanted into foster mothers and stress-associated behaviors were assayed at 2 months of age in the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) and Social Interaction with a Juvenile (SIJ) assay for anxiety and social defects, respectively. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this procedure, a cohort of embryos were collected two days after zygote injection. qPCR revealed that miR-409–3p inhibitor injection into control zygotes did, in fact, induce a large decrease in expression of miR-409–3p at the 4-cell stage (Fig. 2a), In contrast, it had no effect on an unrelated miRNA, miR-34a (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2: Early embryonic inhibition of miR-409–3p levels induce a female-specific anxiolytic phenotype in adult animals.

a. qPCR analysis of miR-409–3p expression in pools of 30–50 4-cell embryos injected as zygotes with either with a negative control or a miR-409–3p inhibitor and cultured to the 4-cell stage. b. and c. Analysis of time spent in the open arms in the elevated plus maze for adult female and male mice injected with either a negative control or miR-409–3p inhibitor as zygotes Data expressed as averages in b and individual mice in c. Control female, n=41; miR-409–3p inhibitor female, n=38; Control male, n=38; miR-409–3p inhibitor male, n=39. Analysis by 2-way ANOVA identified a significant interaction between 409–3p inhibition and sex (P=0.0307), and posthoc Fisher’s LSD analysis of female data identified a significant difference between control and miR-409–3p inhibitor females (P=0.0279). d Top- Total distance traveled in the elevated plus maze for the cohort of animals presented in b. Analysis by 2-way ANOVA did not reveal any significant effects; Bottom- Mean speed during the elevated plus maze trial for the cohort of animals presented in b. Analysis by 2-way ANOVA did not reveal any significant effects.. All data presented as mean +/− SEM. P*<0.05.

Adult F1 females derived from these inhibitor-injected zygotes were tested for anxiety levels using the Elevated Plus Maze. Compared to controls, they spent increased time in the open arms of the EPM (Figs. 2b (averages) and c (individual data points). This is indicative of decreased anxiety in inhibitor-injected zygotes. In contrast, adult males derived from the same set of inhibitor-injected zygotes did not display this anxiolytic phenotype (Figs. 2b and c). The increase in time spent in the open arms by inhibitor injected mice was not accompanied by changes in either total distance travelled in the maze, or speed mice moved (Fig. 2d)

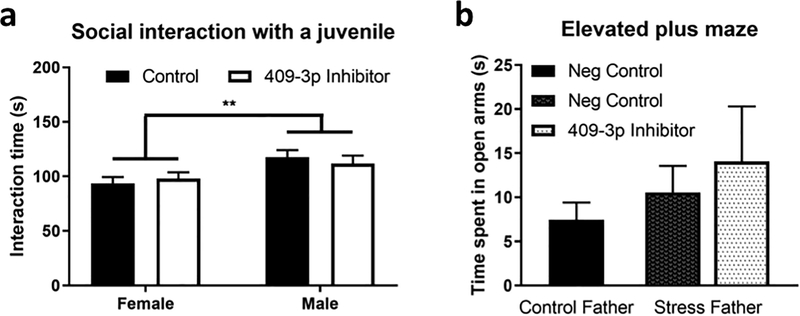

Moreover, neither male nor female mice displayed altered sociability, as measured by the SIJ (Fig. 3a). Thus, the anxiety phenotype induced by inhibiting baseline miR-409–3p in embryos was, as expected, opposite from what we previously observed in offspring of CSI stressed males that received elevated sperm miR-409–3p levels at fertilization. Strikingly, this also reproduced the sex-dependence of the anxiety effect we observed in offspring of CSI stressed males. However, it did not influence all behaviors associated with CSI stress, as it had no effect on sociability.

Figure 3: Early embryonic inhibition of miR-409–3p levels are not sufficient to alter sociability or prevent the development of anxiety in F1 females of stressed fathers.

a. Analysis of time spent performing affiliative interactions with a same-sex juvenile animal. Control female, n=21; miR-409–3p inhibitor female, n=17; Control male, n=19; miR-409–3p inhibitor male, n=18. Analysis by 2-way ANOVA identified a significant main effect of sex (P=0.0037). b. Analysis of time spent in the open arms in the elevated plus maze for adult female mice derived from zygotes from stressed fathers (or control zygotes) injected with negative control miRNAs. Control, n=41, Stress father negative control, n=24, Stress father miR-409–3p inhibitor, n=12. No differences identified by 1-way ANOVA. All data presented as mean +/− SEM. P**<0.01.

Next, we tested whether injection of a miR-409–3p inhibitor could reverse the enhanced anxiety observed in offspring of stressed males. In this case, we injected the inhibitor or negative control inhibitor into zygotes derived from stressed males mated to control females. However, when adult females from control inhibitor-injected zygotes were tested in the EPM they did not display a significantly decreased time in the open arms indicative of elevated anxiety normally seen with offspring of stressed males (Fig. 3b). As described in more detail in the Discussion, a variety of factors could have led to this finding, including required maternal effects on the transmission process, or inhibitory epigenetic alterations associated with handling of zygotes from stressed fathers during micro-injection and their re-implantation into foster mothers.

Thus, while we did produce a phenotype consistent with miR-409–3p contributing to the female specific transmission of anxiety using inhibitor-injected zygotes from control matings, we could not test whether this same manipulation could block elevated anxiety in females derived from stressed fathers.

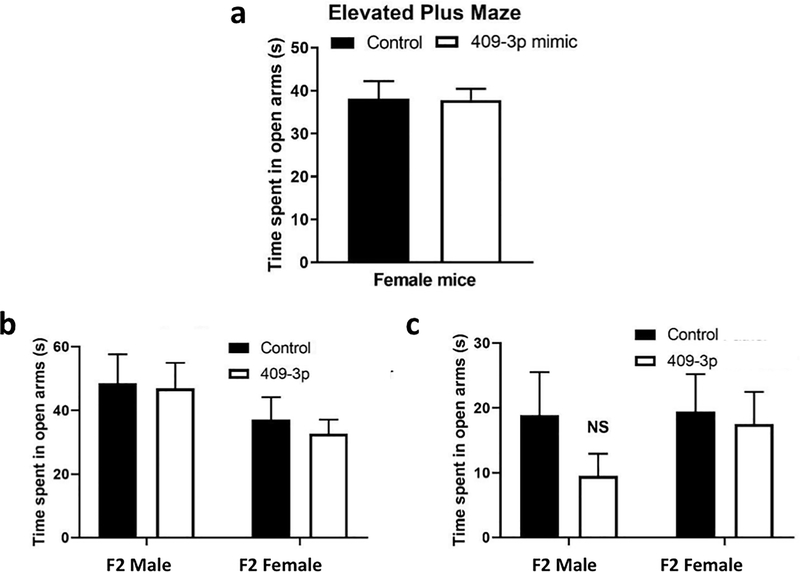

Injection of a miR-409–3p mimic into fertilized zygotes is not sufficient to generate female offspring with elevated anxiety

Next, to investigate whether elevating miR-409–3p levels in early embryos is sufficient to enhance anxiety in offspring, we injected a miR-409–3p mimic or a scrambled miRNA into zygotes derived from the mating of control CD-1 males with control CD-1 female mice. After injection, embryos were again re-implanted into foster mothers and assayed behaviorally at 2 months of age. However, this was not sufficient to elevate anxiety in male or female mice at adulthood (Fig. 4a). Thus, it is likely that if elevated levels of this sperm miRNA influence these processes, they are not sufficient to do so, and additional factors must be required, possibly other miRNAs or maternal factors (see Discussion).

Figure 4: Zygote injection of a miR-409–3p mimic is not sufficient to alter behavior in female mice, and neither injection of mimic or inhibitor affects the F2 generation of offspring.

a. Analysis of time spent in the open arms in the elevated plus maze for adult female mice injected with either a negative control or miR-409–3p mimic as zygotes before reimplantation into foster mothers. Control female, n=45; miR-409–3p inhibitor female, n=64. Analysis by unpaired Student’s t-test did not identify any significant difference between groups. b and c. Analysis of time spent in the open arms in the elevated plus maze for adult F2 female and male offspring from zygotes of control F0 fathers injected with either b, miR-409–3p mimic or a negative control mimic, or c, miR-409–3p inhibitor or a negative control inhibitor. Analysis by 2-way ANOVA (Main effects: miR-409–3p manipulation, Sex) did not identify any significant effects in either case.

Injection of neither inhibitor nor mimic of miR-409–3p produced phenotypes in the F2 generation

Experiments described above investigated whether a mimic or inhibitor of miR-409–3p injected into zygotes can alter behavior phenotypes in F1 female offspring, as stressed males can upon mating. However, F1 male offspring are also affected such that they transmit stress phenotypes to F2 offspring. Thus, to test whether miR-409–3p may be involved in that process, offspring derived from zygotes injected with the miR-409–3p mimic or inhibitor were mated with normal females. When adults, female offspring were tested in the EPM. However, no difference was observed in these females from either set of fathers (Fig. 4b and c). Thus, although inhibition of miR-409–3p in zygotes generates an anxiolytic phenotype in female offspring, neither inhibition nor overexpression of miR-409–3p during early embryogenesis primes male offspring to be able to pass on altered anxiety traits to the next generation.

Discussion

Results of this study have implicated early embryonic levels of miR-409–3p in establishing normal levels of anxiety specifically in adult female mice. This idea is based on our finding that reducing levels of this miRNA in early embryos led to below baseline levels of anxiety in female, but not male, adult mice derived from them. This manipulation displayed behavioral specificity because it had no detectable effect on sociability in adult females. The significance of this finding is supported by our other observation that chronic social instability stress leads to the opposite behavior, anxiogenesis, also specifically in female offspring. This transmission is associated with the opposite change in sperm miR-409–3p levels, an increase in expression, not only in the F0 males exposed to it, but also in their F1 and F2 male offspring who transmit elevated anxiety levels to their female offspring. Moreover, higher than normal times spent in the open arms of the elevated plus maze has been suggested to reflect an increase in risk taking, which is known to be sex dependent (Laviola, Macri, Morley-Fletcher, & Adriani, 2003; Mikics, Barsy, Barsvari, & Haller, 2005).

While these findings imply that normal levels of early embryonic miR-409–3p are necessary for females to express basal levels of anxiety when they mature into adults, it appears that elevated levels of this miRNA in early embryos, at least by injecting a miR-409–3p mimic into zygotes, is not sufficient to enhance anxiety in these animals. This is not surprising, as others have shown that injection of a pool of multiple miRNAs (not including miR-409–3p), but not individual ones, that are elevated in sperm of stressed males into zygotes can produce stress-associated phenotypes (Rodgers et al., 2013). Moreover, in our previous paper (Dickson et al., 2018) we implicated in this process additional miRNAs, miR-34c and miR-449a, that are reduced in sperm of males exposed to CSI stress and in their F1 and F2 male offspring (Saavedra-Rodriguez & Feig, 2013). Moreover, there is significant evidence that there is a maternal component to the transmission of traits induced by paternal experiences that is derived from the maternal detection of defects in their mate. This influences maternal investment in embryo development (Mashoodh, Habrylo, Gudsnuk, Pelle, & Champagne, 2018) that would be bypassed in this type of experiment. Alternatively, elevating miR-409–3p levels in zygotes by injecting a miRNA mimic may have induced non-specific effects that blocked its potential activity.

miR-409–3p is conserved between mice and humans. Most of what we know about its function relates to its elevated levels in human cancer (Josson et al., 2014). Its expression is also altered in the hippocampus in cocaine addiction (Chen, Liu, & Guan, 2013). However, to date validated gene targets do not give clear hints about how they might affect early embryo development to promote behavior changes in adults.

There is large body of evidence supporting the idea that females respond to stress differently than males and have different vulnerabilities to stress related psychiatric disorders(Donner & Lowry, 2013). Thus, a striking aspect of both the transgenerational effects of CSI stress exposure to males and the injection of a miR-409–3p inhibitor into early embryos is that both alter the anxiety levels in female, but not male offspring. This raises the possibility that the degree of female sensitivity to stress and/or to stress-associated anxiety disorders could be influenced by one’s father’s exposure to stress passed on to them epigenetically, or by their mother’s experiences that generate in utero exposures that reduce early embryo miR-409–3p levels. How changes in sperm or embryonic levels of miR-409–3p specifically alter female behavior in adults remains to be determined.

We initiated this study to identify sperm miRNAs that might mediate the effects of CSI on female offspring. The fact that the level of sperm miR-409–3p is elevated not only in sperm of stressed males, but also in their F1 and F2 male offspring supports this hypothesis, as does the observation that inhibition of miR-409–3p in zygotes leads to the opposite phenotype specifically in females. However, a limitation of the study is that we could not test whether inhibiting miR-409–3p in zygotes from stressed males prevents the transmission of stress phenotypes to offspring because the stress phenotype was not transmitted to female offspring after zygotes were injection with control inhibitor miRNA. As mentioned previously, it is possible that this finding was the side effect of the process of removing zygotes after mating and manipulating them before re-implantation. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that these manipulations of zygotes in other settings have been shown to alter their epigenetic state (Lu et al., 2018). Alternatively, as stated previously, maternal contributions to the transmission, a consequence of exposing females to stressed males, could be necessary for transmission of anxiety across generations. If so, this effect would be lost in our paradigm after reimplanting injected zygotes into foster mothers. A maternal contribution to transmission of traits from exposed males has been described in other paradigms (Mashoodh et al., 2018).

Overall, this study identifies a role for early embryo miR-409–3p in the establishment of anxiety levels specifically in females. Identifying early embryo targets of this miRNA that contribute to this and other phenotypes present specifically in adult females induced by manipulating its levels in early embryos are presently being explored.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded National Institute of Health grant #1R01MH107536 to LAF.

REFERENCES

- Chen CL, Liu H, & Guan X (2013). Changes in microRNA expression profile in hippocampus during the acquisition and extinction of cocaine-induced conditioned place preference in rats. J Biomed Sci, 20, 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson DA, Paulus JK, Mensah V, Lem J, Saavedra-Rodriguez L, Gentry A, et al. (2018). Reduced levels of miRNAs 449 and 34 in sperm of mice and men exposed to early life stress. Transl Psychiatry, 8(1), 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz DM, Laplant Q, Watts EL, Hodes GE, Russo SJ, Feng J, et al. (2011). Paternal transmission of stress-induced pathologies. Biol Psychiatry, 70(5), 408–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner NC, & Lowry CA (2013). Sex differences in anxiety and emotional behavior. Pflugers Arch, 465(5), 601–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin TB, Russig H, Weiss IC, Graff J, Linder N, Michalon A, et al. (2010). Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biol Psychiatry, 68(5), 408–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapp K, Jawaid A, Sarkies P, Bohacek J, Pelczar P, Prados J, et al. (2014). Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nat Neurosci, 17(5), 667–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He N, Kong QQ, Wang JZ, Ning SF, Miao YL, Yuan HJ, et al. (2016). Parental life events cause behavioral difference among offspring: Adult pre-gestational restraint stress reduces anxiety across generations. Sci Rep, 6, 39497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josson S, Gururajan M, Hu P, Shao C, Chu GC, Zhau HE, et al. (2014). miR-409–3p/−5p Promotes Tumorigenesis, Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition, and Bone Metastasis of Human Prostate Cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 20(17), 4636–4646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laviola G, Macri S, Morley-Fletcher S, & Adriani W (2003). Risk-taking behavior in adolescent mice: psychobiological determinants and early epigenetic influence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 27(1–2), 19–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Zhang Y, Zheng X, Song X, Yang R, Yan J, et al. (2018). Current perspectives on in vitro maturation and its effects on oocyte genetic and epigenetic profiles. Sci China Life Sci, 61(6), 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashoodh R, Habrylo IB, Gudsnuk KM, Pelle G, & Champagne FA (2018). Maternal modulation of paternal effects on offspring development. Proc Biol Sci, 285(1874). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikics E, Barsy B, Barsvari B, & Haller J (2005). Behavioral specificity of non-genomic glucocorticoid effects in rats: effects on risk assessment in the elevated plus-maze and the open-field. Horm Behav, 48(2), 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reza A, Choi YJ, Han SG, Song H, Park C, Hong K, et al. (2019). Roles of microRNAs in mammalian reproduction: from the commitment of germ cells to peri-implantation embryos. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 94(2), 415–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Bronson SL, Revello S, & Bale TL (2013). Paternal stress exposure alters sperm microRNA content and reprograms offspring HPA stress axis regulation. J Neurosci, 33(21), 9003–9012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers AB, Morgan CP, Leu NA, & Bale TL (2015). Transgenerational epigenetic programming via sperm microRNA recapitulates effects of paternal stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 112(44), 13699–13704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra-Rodriguez L, & Feig LA (2013). Chronic social instability induces anxiety and defective social interactions across generations. Biol Psychiatry, 73(1), 44–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterlemann V, Ganea K, Liebl C, Harbich D, Alam S, Holsboer F, et al. (2008). Long-term behavioral and neuroendocrine alterations following chronic social stress in mice: implications for stress-related disorders. Horm Behav, 53(2), 386–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]