Abstract

Background

Garlic (Allium sativum L.) is a common herb consumed worldwide as functional food and traditional remedy for the prevention of infectious diseases since ancient time. Garlic and its active organosulfur compounds (OSCs) have been reported to alleviate a number of viral infections in pre-clinical and clinical investigations. However, so far no systematic review on its antiviral effects and the underlying molecular mechanisms exists.

Scope and approach

The aim of this review is to systematically summarize pre-clinical and clinical investigations on antiviral effects of garlic and its OSCs as well as to further analyse recent findings on the mechanisms that underpin these antiviral actions. PubMed, Cochrane library, Google Scholar and Science Direct databases were searched and articles up to June 2020 were included in this review.

Key findings and conclusions

Pre-clinical data demonstrated that garlic and its OSCs have potential antiviral activity against different human, animal and plant pathogenic viruses through blocking viral entry into host cells, inhibiting viral RNA polymerase, reverse transcriptase, DNA synthesis and immediate-early gene 1(IEG1) transcription, as well as through downregulating the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. The alleviation of viral infection was also shown to link with immunomodulatory effects of garlic and its OSCs. Clinical studies further demonstrated a prophylactic effect of garlic in the prevention of widespread viral infections in humans through enhancing the immune response. This review highlights that garlic possesses significant antiviral activity and can be used prophylactically in the prevention of viral infections.

Keywords: Allium sativum, Organosulfur compounds, Immunomodulatory, Pandemic, Functional food

Abbreviations: AGE, Aged garlic extract; ARVI, Acute respiratory viral infection; AdV-3, Adenovirus-3; AdV-41, Adenovirus-41; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AIV-H9N2, Avian influenza virus-H9N2; CoV, Coronavirus; CBV-3, Coxsackie B −3; CPE, Cytopathic effect; DAS, Diallyl sulfide; DADS, Diallyl disulfide; DATS, Diallyl trisulfide; DDB, Dimethyl-4,4′-dimethoxy-5,6,5′,6′-dimethylene dioxybiphenyl-2,2′-dicarboxylate; ECHO11, Echovirus-11; ERK, Extracellular-signal-regulated kinase; ECM, Extracellular matrix; FDA, Food and drug administration; GE, Garlic extract; GO, Garlic oil; GRAS, Generally regarded as safe; GLRaV‐2, Grapevine leafroll‐associated virus 2; HSV-1, Herpes simplex virus-1; HSV-2, Herpes simplex virus-2; HAV, Hepatitis A virus; Hp, Haptoglobin; HIV-1, Human immunodeficiency virus-1; HRV-2, Human rhinovirus type 2; HPV, Influenza B virus Human papillomavirus; HCMV, Human cytomegalovirus; IAV-H1N1, IBV Influenza A virus-H1N1; IEGs, Immediate-early genes; IEG1, Immediate-early gene 1; LGE, Lipid garlic extract; NK, Natural killer; MARS-CoV, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus; MAPK, Mitogen activated protein kinase; MDCK cells, Madin-darby canine kidney cells; MeV, Measles virus; NDV, Newcastle disease virus; NA, Not available; OSCs, Organosulfur compounds; PIV- 3, Parainfluenza virus-3; PRV, Porcine Rotavirus; PVY, Potato Virus Y; PRRSV, Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus; PGE, Powdered garlic extract; RCTs, Randomized clinical trials; RMCW, Recalcitrant multiple common warts; RV-SA-11, Rotavirus SA-11; SAMG, S-allyl-mercapto-glutathione; SAMC, S-allyl-mercaptocysteine; SARS-CoV, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; SI, Selectivity index; SAC, Serum antioxidant concentration; SWV, Spotted wilt virus; SRGE, Sustained release garlic extract; VSV, Vesicular stomatitis virus; VV, Vaccinia virus

1. Introduction

Countries around the world are struggling to identify a prevention and/or treatment for COVID-19. The world has previously experienced viral diseases as an epidemic or pandemic; such as the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak in 2003, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MARS-CoV) occurrence in 2012 and the Ebola outbreak in West Africa in 2014 (Martinez et al., 2015). Infectious diseases are one of the main cause of premature death worldwide, as well as continue to exists as a constant danger to human life (Ganjhu et al., 2015). Prevention of viral infections is challenging due to fast-emerging drug resistance, rapid adaptation and unique metabolic properties (Erdem & Ünal, 2015; Howard & Fletcher, 2012). Viruses can undergo subtle genetic changes by mutation and create novel virus from known genus or family (Fleischmann, 1996). Sometimes these mutations can result in creating novel, life threating viruses such as COVID-19. Immunocompromised people including people with cancer, diabetes, malnutrition and certain genetic disorders, are more susceptible to viral infections (Englund et al., 2011). Over the past decade the global health community has focused on planning for the prevention and control of a viral pandemic (Koonin & Patel, 2018). Prompt treatment of infected people with antiviral medication can cure the illness, alleviate the severity, shorten the disease as well as minimize the outbreak (Koonin & Patel, 2018). Most of the current antiviral drugs have some limitations including toxic side effect, drug resistance and poor bioavailability (Field & Wainberg, 2011). Therefore, the discovery of novel antiviral drugs could play an essential role in a pandemic response as is the case in the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Natural products are an excellent starting point for drug discovery. Medicinal plant extracts and related products, have long been used to treat a wide range of infections including viral infection, and their purified phytoconstituents are an excellent precursor for new antiviral drugs (Ganjhu et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2014). For many plant extracts inhibitory activity of replications of various viruses have been reported; namely herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2), human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and SARS virus (Mukhtar et al., 2008). Plant extracts have also shown broad-spectrum activity against drug resistant viruses which might be linked to their many multifunctional components (Tolo et al., 2006). The mechanism by which these extracts, or their purified constituents, display their antiviral action may vary depending on the virus strains and viral life cycle including viral entry, fusion, replication, assembly and virus–host-specific interactions (Lin et al., 2014). Immunomodulatory properties are one the potential activity of herbal medicine products that can fight viral infections. Several plants have shown to enhance the immune system of the host to boost its antiviral defence (Raza et al., 2015). Therefore, plants might be an exciting source for the development of new antiviral drugs.

Garlic (Allium sativum L.) is an annual bulbous herb of the Alliaceae family that are native to Central and South Asia. It has been used for culinary and spiritual purposes for many years. Now-a-days garlic is cultivated all over the world mainly in dry and hot climate. China, India, South Korea, Egypt and USA have been reported as the countries with the highest garlic production country in the world (Medina & Garcia, 2007; Rehman et al., 2019, p. 768). For thousands of years garlic has been used as a functional food, spice and seasoning herb, as well as an effective, traditional medicine against different ailments including viral diseases (Ayaz & Alpsoy, 2007; Rehman et al., 2019, p. 768; Tsai et al., 1985). In 1720 garlic was successfully used to save the Marseille population from the plague (Petrovska & Cekovska, 2010). The consumption of fresh and cooked, as well supplementation with garlic are well tolerated at a reasonable level in or with a meal and regarded as “generally safe (GRAS)” by the American Food Drug Administration (FDA) (Holub et al., 2016). Garlic has been used for centuries as an ethnomedicinal plant to treat infectious diseases. It has been reported that fresh garlic ingestion or intravenous preparation of its extracts is used to treat various viral infections or cryptococcal meningitis patients, respectively, in China (Tsai et al., 1985). In Asia and Europe, garlic is used to treat the common cold, fever, coughs, asthma and wounds (Rehman et al., 2019, p. 768). Garlic oil has also been used to relieve pain due to ear infections (Al Abbasi, 2008). Garlic has been used in African traditional medicine, such as in Ethiopia and Nigeria, to treat a number of infections including sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis, respiratory tract infection and wounds (Abiy & Asefaw, 2016; Gebreyohannes & Mebrahtu, 2013). Garlic has been reported to have antiviral activity against human, animal and plant viral infections (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

List of viruses with their family and common infection syndrome on which garlic extract and its organosulfur compounds reported to have antiviral activity.

| Name of virus | Family | Common infection/Syndrome | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenovirus-3 (AdV-3); Adenovirus-41(AdV-41) | Adenoviridae | Cold and respiratory tract illness | Khanal et al. (2018) |

| Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) | Arteriviridae | Reproductive and respiratory tract illness in animal | Dietze et al. (2011) |

| Coronavirus (CoV); Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | Coronaviridae | Cold and respiratory tract infection (both in human and animal) | Mehrbod et al. (2013) |

| Dengue virus (DENV) | Flaviviridae | Hemorrhagic fever | Alejandria (2015) |

| Herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1); Herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2); Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) | Herpesviridae | Genital herpes, cold sores and other sexual infection | (Straface et al., 2012; Taylor, 2003) |

| Influenza A virus subtype H9N2 (IAV-H9N2); Influenza B virus (IBV); Influenza A virus-H1N1 (IAV-H1N1) | Orthomyxoviridae | Flu in both human and animal | Klenk et al. (2008) |

| Coxsackie B −3 (CBV-3), Echovirus-11 (ECHO); Enterovirus-71(EV-71) | Picornaviridae | Minor febrile illness, aseptic meningitis, encephalitis and paralysis | (Dalldorf & Gifford, 1951; Khetsuriani et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2002) |

| Human rhinovirus-2 (HRV-2) | Cold and respiratory tract infection in human | Rossmann et al. (1985) | |

| Hepatitis A virus (HAV) | Infectious disease of the liver in human | Matheny & Kingery (2012) | |

| Measles virus (MeV); Newcastle disease virus (NDV); Parainfluenza virus-3 (PIV- 3) | Paramyxoviridae | Cold and respiratory tract illness in human | Enders (1996) |

| Vaccinia virus (VV) | Poxvirus | Skin infection, fever and common cold | Silva et al. (2010) |

| Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) | Rhabdoviridae | Foot and mouth disease in animals and flu-like illness in human | Ludwig & Hengel (2009) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1); Reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV) | Retroviridae | Causes immunosuppression in human (HIV) and poultry (REV) | (Wang et al., 2017; Palefsky & Holly, 2003; ) |

| Porcine Rotavirus (PRV); Rotavirus SA-11 (RV-SA-11) | Reoviridae | Gastrointestinal infection and diarrhoea in human and animal | (Crawford et al., 2017; Vlasova et al., 2017) |

| Potato Virus Y (PVY) | Potyviridae | Virus infecting potato | Kreuze et al. (2020) |

| Spotted wilt virus (SWV) | Bunyaviridae | Virus infecting Tomato | Abad et al. (2005) |

| Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 2 (GLRaV-2) | Closteroviridae | Virus infecting grapevine | Alkowni et al. (2011) |

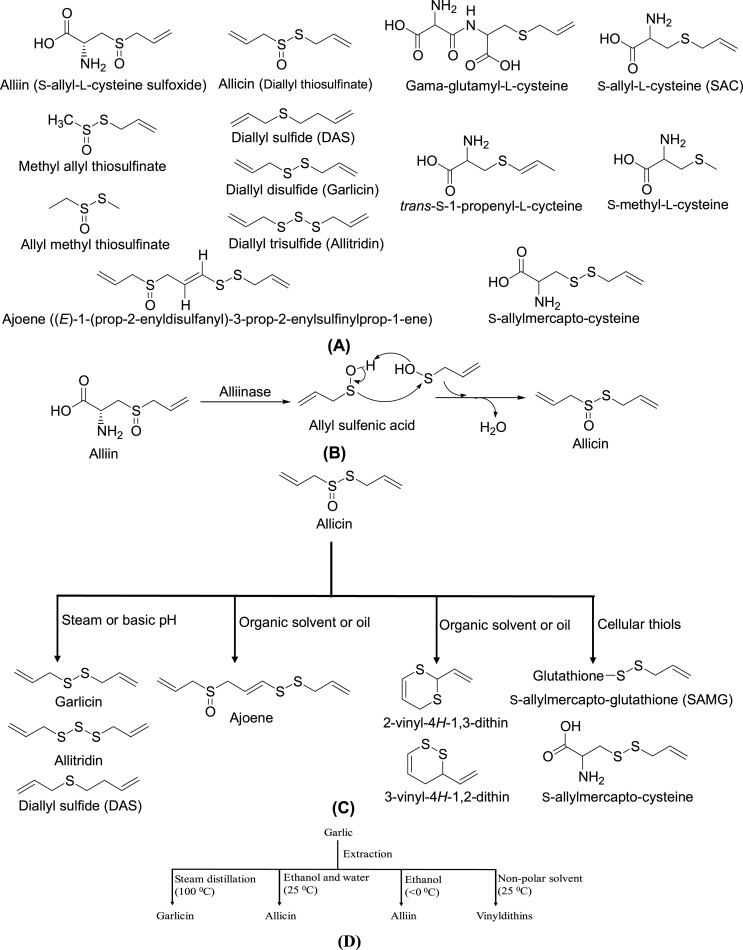

Although garlic has been used since ancient time for its medicinal purposes, the exploration of its active constituents began only recently. The OSCs of garlic are to be the main bioactive constituents, and are also responsible for its pungent odor (Omar & Al-Wabel, 2010). More than thirty sulfur containing compounds belonging to two main chemical classes, l-cysteine sulfoxides and γ-glutamyl-l-cysteine peptides, are presents in garlic (Fig. 1 A) (Yamaguchi & Kumagai, 2020). Alliin (S-allyl-l-cysteine sulfoxide) is the most abundant sulfur compound present in fresh and dry garlic (10–30 mg/g) (Lawson, 1998). Alliin can quickly convert into allicin (diallyl thiosulfinate) via alliinase enzymes upon chopping, mincing, crushing or chewing of fresh garlic (Fig. 1B) (Borlinghaus et al., 2014; Lawson, 1998). Allicin itself is very unstable and can be decomposed in-vitro into other OSCs including diallyl sulfide (DAS), diallyl disulfide (garlicin or DADS), diallyl trisulfide (allitridin or DATS), andajoene and vinyl-dithiins (Fig. 1C) (Amagase, 2006; Harris et al., 2001). Allicin can interact with cellular thiols such as glutathione and l-cysteine in-vivo and form S-allyl-mercapto-glutathione (SAMG) and S-allyl-mercaptocysteine (SAMC), respectively (Fig. 1C) (El-Saber Batiha et al., 2020; Trio et al., 2014). These compounds may be responsible for the detrimental structural changes of pathogen's proteins (Borlinghaus et al., 2014). On the other hand, γ-glutamyl-l-cysteine peptide and its dipeptide derivative such as γ-glutamyl-S-allyl-l-cysteine, γ-glutamyl-methyl-cysteine, and γ-glutamyl-propylcysteine are water soluble and stable while garlic is crushed (Fig. 1A) (Higdon, 2016). Harries et al. found that different extraction methods can yield different OSCs as principle components (Fig. 1D) (Harris et al., 2001). A commercial garlic preparation that contained varying OSCs has also been reported by other research groups who investigated (Table 2 ) (Amagase, 2006; Ginter & Simko, 2010; Higdon, 2016; Staba et al., 2001). Garlic also contains non-sulfur constituents including lectins, flavonoids (kaempferol, quercetin and myricetin), polysaccharides (fructan), steroids, saponins, fatty acids (lauric and linoleic acid), several enzymes, vitamins (e.g., A, B1 and C), allixin, minerals (e.g., Ca, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Zn and Se) and amino acids which are likely having additive or synergistic effects with OSCs (Amagase, 2006; Josling, 2005; Keyaerts et al., 2007; Li et al., 2017; Sharma, 2019). Allicin was reported as one of the main OSCs that was considered one of the principle compounds responsible for antiviral activity (Wang et al., 2017; Weber et al., 1992), immunomodulatory (Arreola et al., 2015), anti-inflammatory (Metwally et al., 2018), antioxidant (Prasad et al., 1995) and other pharmacological properties (Borlinghaus et al., 2014). Pre-clinical studies, both in-vitro and in-vivo, showed that allicin-derived OSCs such as ajoene, allitridin, garlicin and DAS also possess potential antiviral (Fang et al., 1999; Keyaerts et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2004; Terrasson et al., 2007; Walder et al., 1997), immune enhancing (Hall et al., 2017; Li et al., 2013; Yi et al., 2005) and other therapeutic activities (El-Saber et al., 2020; Kaschula et al., 2010; Yi, L. & Su, 2013).

Fig. 1.

Organosulfur compounds of garlic: (A) Structure of OSCs identified in garlic; (B) Biosynthesis of allicin from alliin; (C) Transformation of allicin to its derivatives at different condition; (D) Extraction of major sulfur constituents (other OSCs also yielded as minor amount) from garlic with different solvent systems.

Table 2.

List of different commercial garlic preparations, method of preparation and their principle OSCs.

| Garlic preparation | Method of preparation | Name of main OSCs | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh garlic clove | Slice of fresh raw garlic | Alliin and γ-Glutamyl-l-cysteine peptides and different percentage of allicin and its derivatives | Higdon (2016) |

| Dried garlic | Garlic cloves are sliced and dried at a low temperature to prevent alliinase inactivation | Alliin and γ-Glutamyl-l-cysteine peptides and different percentage of allicin and its derivatives | Staba et al. (2001) |

| Garlic oil | Steam distillation of crushed garlic cloves | Garlicin, allitridin, Allyl methyl trisulde and allicin | Staba et al. (2001) |

| Garlic oil macerate | Incubation of crushed garlic cloves in oil at room temperature | Vinyldithiins, (E/Z)-ajoene, allitridin and allicin | Brace (2002) |

| Garlic powder | Garlic cloves are sliced and dried at a low temperature and then pulverized to make garlic powder | Alliin and γ-Glutamyl-l-cysteine peptides and different percentage of allicin and its derivatives | Staba et al. (2001) |

| Garlic juice | Blending of peeled garlic cloves with distilled water | Allicin, Vinyldithiins, garlicin and allitridin | Yu & Wu (1986) |

| Garlic tincture | Maceration of chopped garlic with vinegar/alcohol for 3 weeks | Alliin, allicin and ajone | Santos and Carvalho (2014) |

| Aged garlic extract | Garlic cloves are incubated in a solution of ethanol and water for up to 20 months | Allyl-l-cysteine (SAC), S-Allyl-mercapto-cysteine (SAMC), trans-S-1-Propenyl-l-cysteine and minimum percentage of allicin and its derivatives | Staba et al. (2001) |

Pre-clinical investigations (in-vitro and in-vivo) of garlic extract (GE) and its OSCs have shown antiviral activity against a wide range of viral infections including flu and respiratory infections (Chavan et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2011; Choi, 2018; Liu et al., 2013; Mehmood et al., 2018; Mehrbod et al., 2009; Mehrbod et al., 2013; Mohajer Shojai et al., 2016; Rasool et al., 2017; Tsai et al., 1985; Weber et al., 1992), immunosuppression (“Garlic extract for HIV?", 1998; Kun Silprasit et al., 2011; Shoji et al., 1993; Tatarintsev et al., 1992; Walder et al., 1997), genital herpes (Romeilah et al., 2010; Weber et al., 1992), neurological infections (Luo et al., 2001; Meléndez-Villanueva et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2016), gastrointestinal infections (Al-Ballawi et al., 2017; Weber et al., 1992), plant infections (Mohamed, 2010; Shyam & Ashish, 2011; Wang et al., 2020) and others (Liu et al., 2013; Seo et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017 Weber et al., 1992) (Table 3, Table 4 ). Further, randomized clinical trials on different commercial garlic preparations also showed that garlic plays a significant therapeutic role in various viral infections such as cold and flu, viral-induced hepatitis, viral-associated warts, as well as immune enhancing activity in viral infected patients (Table 5 ). The proposed mechanism of their antiviral activity was reported to be the inhibition of the viral cell cycle, enhancing host immune response or reduction of cellular oxidative stress. However, there is no systematic review to-date that covers the antiviral activity of garlic and its OSCs in pre-clinical and clinical studies in detail. The aim of this review is to summarize and highlighted the potential antiviral effects of garlic and its OSCs with focus on underlying mechanisms of action by compiling both preclinical and clinical published data using afore-mentioned databases.

Table 3.

Pre-clinical investigations (in-vitro and in-vivo) of antiviral activity of garlic extract.

| Test model/Assay | Virus species | Mode of Propagation | EC50 (mg/ml) | Selectivity index (SI) | Preparation | Proposed mechanism of action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque reduction assay | MeV | VERO cells | 0.01 | 16.05 | Aqueous extract in gold nanoparticles | Directly inhibit viral infection by blocking viral particles entry | Meléndez-Villanueva et al. (2019) |

| Direct pre-infection incubation and plaque reduction assays | HSV-1 | VERO and HeLa cells | 31 | NA | Fresh garlic extract | Inhibition of virus entry via disruption of viral envelope and cell membrane | Weber et al. (1992) |

| HSV-2 | 63 | ||||||

| PIV- 3 | 31 | ||||||

| VV | 250 | ||||||

| VSV | 8 | ||||||

| HRV-2 | >100 | ||||||

| Toxicity assay | AIV-H9N2 | Chick embryo | 15 | 1.6 | Aqueous extract | NA | Rasool et al. (2017) |

| Early antigen assay | HCMV | In-vitro cells | NA | NA | Extract | Antiviral effect through enhancing immune responses | Guo et al. (1993) |

| Toxicity assay | CoV | Chicken embryo | 1 | NA | Aqueous extract | Inhibition of viral replication | Mohajer Shojai et al. (2016) |

| Direct pre-infection incubation assays | PRV | MA104 cells | 0.03 | NA | Aqueous extract | NA | Rees et al. (1993) |

| Hemagglutination assay | IAV-H1N1 | MDCK cells | 10 | 2 | Ethanolic extract | Inhibition of H1N1 virus by inhibiting viral nucleoprotein synthesis and polymerase activity | Chavan et al. (2016) |

| Plaque reduction assays | HSV-1 | Rabbit skin cells | 0.015 | 100 | Extract | NA | Tsai et al. (1985) |

| Cytopathic effect (CPE) | IAV-H1N1 | MDCK cells | 0.1 | NA | Garlic oil | Reduced visible cytopathic effects in IAV-H1N1 infected cells | Choi (2018) |

| HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitory assay | HIV-1 | Viral cells | 0.06 | NA | n-Hexane extract | Inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase | Kun Silprasit et al. (2011) |

| CPE and hemagglutination assay | IAV-H1N1 | MDCK cells | 0.01 | 10 | Fresh extract | Inhibitory effect on the virus penetration and proliferation in cell culture. | Mehrbod et al. (2009) |

| Anti-influenza activity | IAV and IBV | In-vitro | NA | Extract | NA | Fenwick & Hanley (1985) | |

| Immunofluorescent assay | IAV-H1N1 | MDCK cells | 0.01 | 10 | Fresh extract | Inhibition of the replication of influenza A virus | Mehrbod et al. (2013) |

| MTT and plaque reduction assays | AdV-3 and AdV-41 | A549 cells | 3.5 | 1 | Aqueous extract | NA | Chen et al. (2011) |

| CPE assay | HSV-1 | VERO cells | 0.32 | NA | Garlic oil | NA | Romeilah et al. (2010) |

| CPE and plaque reduction assay | CBV3 | HEL and VERO cells | 0.005 | 2.5 | Extract | Inhibitory effect on the virus penetration in host cells | Luo et al. (2001) |

| CPE and plaque reduction assay | ECHO-11 | HEL and VERO cells | 0.005 | 2.5 | Extract | Inhibitory effect on the virus penetration in host cells | Luo et al. (2001) |

| CPE assay | IAV-H1N1 | MDCK cells | >0.1 | NA | Garlic oil | NA | Zheng et al. (2013) |

| Plaque reduction assay | RV-SA-11 | MA-104 cells | 0.025 | NA | Aqueous extract | NA | Al-Ballawi et al. (2017) |

| Plaque reduction assay | HAV | FRhK-4 cell line | 0.05 | NA | Methanol extract | Virucidal effect on HAV during co-treatment with garlic extract | Seo et al. (2017) |

| Hemagglutination assay | NDV | VERO cells | 0.025 | ND | Ethanolic extract | Inhibit viral replication by blocking the viral fusion into the cells | Mehmood et al. (2018) |

| Direct pre-infection incubation assays in | IBV | Chicken egg | 0.15 | 10 | Extract | NA | Tsai et al. (1985) |

| Growth performance and immune responses of weaned pigs infected with PRRSV virus | PRRSV | Weaned pigs | 10 | NA | Garlic extract with 40% propyl thiosulfonates | Alleviate viral infection of weaned nursery pigs by enhancing pigs' immune responses through reduction of viral load, proinflammatory cytokine (TNF-α, and IL-1β), and improved B and CD8+ T cells and haptoglobin (Hp) | Liu et al. (2013) |

| Hemagglutination and hemagglutination inhibition assay | NDV | Chick embryo | 50 | NA | Aqueous extract | Inhibition of the virus attachment into the host cells | Harazem et al. (2019) |

| Virus infected field-grown grapevine cv plantlets | GLRaV-2 | Grapevine cv. plantlets | 10 | NA | Extract | Trigger plant defense responses including increased expression of pathogenesis-related protein genes (PR genes) and enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes. | Wang et al. (2020) |

| Antiviral activity assessed by number of local lesions in plant | PVY | Chenopodium amaranticolor plant | 10 | NA | Garlic juice | Reducing the local lesions produced by PVY | Mohamed (2010) |

| Antiviral activity assessed by number of local lesions in plant | SWV | C. amaranticolor plant | 1 | NA | Extract | Reducing the local lesions produced by PVY | Shyam & Ashish (2011) |

Table 4.

Pre-clinical investigations (In-vitro and In-vivo) into the antiviral activity of OSCs isolated from garlic (A. sativum).

| Compound name | Test model | Virus species | Mode of Propagation | EC50 (mM) | Selectivity index (SI) | Mechanism of Action | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajoene | Anti-HIV activity | HIV-1 | CD+ cells | NA | NA | Prevention of HIV-induced destruction of CD + cells and enhance cellular immunity | (“Garlic extract for HIV?", 1998) |

| HIV-infected platelet aggregation and fusion assays | HIV | H9 and CEM13 cells | 0.045 | NA | Inhibition of adhesive interactions and fusion of leukocytes | Tatarintsev et al. (1992) | |

| HCMV spreading assay | HCMV | HFF cells | 0.01 | NA | Induction of apoptosis of infected cells | Terrasson et al. (2007) | |

| HIV-1 induced cellular toxicity, virus adsorption inhibition and virus replication assays | HIV-1 | Molt-4 cells | 0.0003 | 5.4 | Inhibition of virus-cell attachment and viral reverse transcriptase as well as it blocked further destruction of CD4 T-cells | Walder et al. (1997) | |

| Allicin | Direct pre-infection incubation and plaque reduction assays | HSV- 1 | VERO and HeLa cells | 0.15 | NA | Inhibition of virus entry via disruption of viral envelope and cell membrane | Weber et al. (1992) |

| HSV-2 | 0.62 | ||||||

| PIV- 3 | 0.15 | ||||||

| VV | NA | ||||||

| VSV | 0.15 | ||||||

| HRV-2 | 3.4 | ||||||

| Reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV)-induced immune dysfunction assay | REV | 1-Day old spf white leghorn chickens | 0.92 mM/kg | NA | Inhibition of REV replication via downregulation of ERK/MAPK pathway as well as alleviation of REV-induced inflammation and oxidative damage | Wang et al. (2017) | |

| Alliin | Oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory assay | DENV | Huh-7 and U937 cells | 0.003 | NA | Inhibition of inflammation via reduction of oxidative stress | Hall et al. (2017) |

| Allyl methyl thiosulfinate | Direct pre-infection incubation and plaque reduction assays | HSV- 1 | VERO and HeLa cells | 0.37 | NA | Inhibition of virus entry via disruption of viral envelope and cell membrane | Weber et al. (1992) |

| HSV-2 | 0.74 | ||||||

| PIV- 3 | 2.9 | ||||||

| VV | 2.0 | ||||||

| VSV | 0.37 | ||||||

| HRV-2 | NA | ||||||

| Methyl allyl thiosulfinate | Direct pre-infection incubation assays | HSV- 1 | VERO and HeLa cells | 0.74 | NA | Inhibition of virus entry via disruption of viral envelope and cell membrane | Weber et al. (1992) |

| HSV-2 | 2.9 | ||||||

| PIV- 3 | 2.9 | ||||||

| VV | 2.9 | ||||||

| VSV | 0.37 | ||||||

| HRV-2 | NA | ||||||

| Diallyl trisulfide (Allitridin) | Murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV)- induced hepatitis in mice | HCMV | Mice | 0.14 and 0.42 mM/kg/day for 18 and 14 days | NA | Reduced of MCMV DNA load, plasma alanine aminotransferase and histopathological lesions | Liu et al. (2004) |

| MCMV-induced hepatitis in mice | HCMV | Mice | 0.14 mM/kg/day for 14 days | NA | Decreased liver damage via reduced the levels of serum ALT and MCMV IE genes expression (viral replication) in liver | Fang et al. (1999) | |

| Plaque reduction assay | HCMV | HEL cells | 0.04 | NA | Inhibit viral DNA synthesis through inhibition of HCMV immediate-early antigen (IEA) expression | Fang et al. (1999) | |

| Plaque reduction assay | HCMV | HEL cells | 0.02 | 16.7 | Inhibition of viral replication via suppression viral IEG gene transcription | Zhen et al. (2006) | |

| Plaque reduction assay | HCMV | HLE cells | 0.05 | NA | Inhibition of viral replication via suppression viral IEG gene transcription | Shu et al. (2003) | |

| MCMV-induced regulatory T cell amplification assay | HCMV | Mice | 0.14 mM/kg/day for 120 days | NA | Upregulated CMV-induced Treg expansion and Treg-mediated anti-MCMV immunosuppression | Li et al. (2013) | |

| MCMV-induced expression of transcription factors T-bet and GATA-3 in mice | HCMV | Mice | 0.14 mM/kg/day for 120 days | NA | Enhancing immune response against CMV and clear CMV via upregulation of the transcription factor T-bet and the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ as well as downregulation of the transcription factor GATA-3 and the Th2 cytokine IL-10 | Yi et al. (2005) | |

| Diallyl sulfide (DAS) | Oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory assay | DENV | Huh-7 and U937 cells | 1.0 | NA | Inhibition of inflammation via reduction of oxidative stress | Hall et al. (2017) |

| Diallyl disulfide (Garlicin) | Oxidative stress and anti-inflammatory assay | DENV | Huh-7 and U937 cells | 1.0 | NA | Inhibition of inflammation via reduction of oxidative stress | Hall et al. (2017) |

| CPE assay | EV-71 | 0.09 | NA | NA | Wang et al. (2016) | ||

| CPE assay | HIV | CEM/LAV-1 cells | 0.03 | 2.59 | Inhibition of HIV-1 replication | Shoji et al. (1993) | |

| Lectins (ASA and ASA1) | Tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay | SARS-CoV | VERO cells | >0.004 | NA | Inhibition of early replication cycle (viral attachment) and then inhibition of at the end of infectious virus cycle | Keyaerts et al. (2007) |

Table 5.

Randomized controlled clinical investigations of garlic (A. sativum) and its OSCs in viral infections.

| Study design Gender (n) | Number and characteristics of patients/diseases | Preparation of garlic/active molecules | Experimental intervention (dose, type and duration) | Control intervention (dose, type and duration) | Treatment group | Assessment tool | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs with two parallel groups; | 146 subjects including 73 in each group with mean age 52 yrs. | Allicin containing garlic extract | Allicin-garlic capsule, one capsule/day for 84 days followed 6 days follow-up | Placebo, | Allicin-garlic capsule (n = 73) and placebo (n = 73) | Five-point scale to examine health and recorded number of cold and flu infections and symptoms in a daily diary | (Josling, 2001) |

| a. active group (M = 32, F = 29) and | One placebo capsule/day for 84 days followed 6 days follow-up | ||||||

| b. placebo group (M = 41, F = 44) | |||||||

| RCTs with two parallel stage study; | First stage: 172 children in tolerance group and 468 control with mean age 7–16 yrs. | Garlic extract | First stage garlic tablet (600 mg/day) for 150 days and 2nd stage garlic tablet (300 mg/day) for 150 days | First stage: One placebo tablet/day for 150 days | Frist stage: Garlic tablet (n = 172) and placebo (n = 468) and 2nd stage: Garlic tablet (n = 42) and placebo (n = 41) and benzimidazole tablet (n = 73) | Initial stage: tolerance and ARVI morbidity compared to control (placebo only). | Andrianova et al. (2003) |

| a. First stage tolerance study with two parallel group (172 treated children and 468 placebo control); | 2nd stage: 42 children in efficacy group, 41 control group and 73 benzimidazole group with mean age 10–12 yrs. | 2nd Stage: One placebo tablet/day for 150 days | In second stage: ARVI morbidity compared with control and benzimidazole-treated children | ||||

| b. 2nd stage efficacy study with three parallel groups (42 treated children, 41 placebo control and 73 benzimidazole) | |||||||

| RCTs with two parallel groups; | 120 subjects including 60 in each group with mean age 26 yrs | Aged garlic extract | AGE capsule (2.56 gm/cap) One capsule/day for 90 days | Placebo, | AGE capsule (n = 60) and placebo (n = 60) | Reduction of severity of cold and flu illness, days of symptom exists, number of incidences and work/school missed as well the role of specific innate-like lymphocytes (γδ-T cell and NK cell) and antioxidant parameters | (Nantz et al., 2012; Percival, 2016) |

| a. garlic extract group and | One placebo capsule/day for 90 days | ||||||

| b. placebo group (M = 48 and F = 72) | |||||||

| RCTs with two parallel groups; Lipid garlic extract group (M = 6 and F = 19) and | 50 subjects including 25 in each group with mean age 25+ yr | Lipid garlic extract | LGE applied to the largest one of recalcitrant | Placebo (saline), placebo applied twice day for 28 days | LGE (n = 25) and placebo (n = 25) | Size of warts and photographic comparison. The response was considered complete (complete disappearance), partial (reduced size in 25%–100%) and no response (0–25% decrease in size) as well as also examined serum TNF-α (0 and 4th week) and adverse effect up to 6 months | |

| placebo group (M = 20 and F = 5) | multiple common warts (RMCW) twice per day for 28 days | Kenawy et al. (2014) | |||||

| RCTs with four parallel groups of 88 subjects; | 79 subjects including appx. 20 in each group of chronic hepatitis with different age | DDB with garlic oil | Capsule contains 25 mg DDB plus 50 mg garlic oil (group B 2 cap/day; group C 3 cap/day; group D 6 cap/day; for 42 days with 7 days follow-up) | Placebo, | Capsule (n = 22/21/17) and placebo (n = 19) | Changes in surrogate marker ALT and AST for hepatitis liver injury by HBV or HCV. Safety and tolerability were assessed based on adverse events and laboratory test results. | Lee et al. (2012) |

| one placebo group and three escalating dose groups (2, 3, or 6 study drug capsules a day) | one placebo capsule/day for 42 days with 7 days follow-up | ||||||

| RCTs with two parallel groups; | 52 subjects including 26 in each group of frequent travelers with average age 38 yr | Cellulose only or Cellulose and powdered garlic extract combined | One sniff (cellulose and PGE combined) in each nostril every day for 56 days and if an infection developed, participants instructed to take up to 3 sniffs per nostril on each day until infection reduced | One sniff (cellulose only) in each nostril every day for 56 days and if an infection developed take 3 sniffs per nostril on each day until infection reduced | Active group (cellulose and PGE combined) (n = 26) and placebo (cellulose only) (n = 26) | Five point scale to examine health and number of infections, day of recovery start and day of fully recovery, variety of symptoms in their daily diary | Hiltunen et al. (2007) |

| one placebo group (n = 26) and | |||||||

| one active group (n = 26) | |||||||

| RCTs with two parallel groups of 35 subjects and all male; | 33 subjects; all clinically diagnosed genital warts who had more than two warts on both sides of genital region enrolled in the study with mean age 33 yr | Garlic extract (10%) in polyethylene glycol application on warts | Garlic extract (10%) on left side warts (active group) and cryotherpary with liquid nitrogen on right side warts (placebo gropu) for 56 days | Placebo, cryotherpary with liquid nitrogen on right side warts twice a day for 56 days | Garlic extract (10%) in polyethylene glycol on left side warts by cotton swab twice a day for 56 | Size and number of warts lesions reduced. | Mousavi et al. (2018) |

| one placebo group and | |||||||

| one active group | |||||||

| RCTs with two parallel groups of 3° subjects and all children; | 30 subjects; all children with cellular immunodeficiency as a prophylaxis of recurrent infections, mainly of viral origin with age 3–15 yrs | Inosine pranobex (50 mg/kg) as active | Inosine pranobex | Control group, | Inosine pranobex | Clinical and immunological investigations before and after the treatment (counted for CD3+ T and CD4+ T lymphocytes number as well improvement of subject function) | Gołebiowska-Wawrzyniak et al. (2005) |

| one control group and one active group | (50 mg/kg/day) for active group and garlic extract (50 mg/kg/day) in control group for 10 days | garlic extract (50 mg/kg) b.w/day for 10 days | (50 mg/kg//day) for 10 days |

RCTs = Randomized clinical trials.

2. Literature search strategy and data extraction

A number of databases including PubMed, Cochrane library, Google Scholar and Science Direct were used to search literature on garlic and its OSCs for this review. A complete literature search was conducted using the above databases with the term ‘Garlic’ or ‘Allium sativum’ along with ‘antiviral activity’, ‘viral infections’, ‘antimicrobial activity’, ‘viral replication’ ‘immunomodulatory’ and ‘immune enhancing activity’. Only reports that were in English were considered in this review. Antiviral studies of garlic and its OSCs were included in this systematic review if they covered the following information: (i) in-vivo studies, (ii) in-vitro studies, (iii) studies indicating the dose, EC50 or viral selectivity index (SI) (iv) clinical trials of garlic in viral infections specifying dose, intervention, placebo, parallel group and duration of treatment (v) studies that include garlic extracts or its isolated OSCs and (vi) studies that incorporated the mechanisms of actions of garlic and its OSCs.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. In-vitro and in-vivo antiviral activity of garlic extract and its OSCs

Garlic has been used traditionally as an herbal medicine to treat various infectious diseases including cold/flu and other viral infections (Kun Silprasit et al., 2011; Lissiman et al., 2014; Tsai et al., 1985). Contemporary in-vitro and in-vivo pharmacological investigations of different garlic extracts and its isolated OSCs have confirmed the reasons for garlic's ethnomedicinal use in various viral infections. Table 1 lists the species and family names of the viruses against which garlic and its OSCs are active. Included are literature data on antiviral activity against a number of viruses that cause widespread infections including flu and respiratory infections (influenza, parainfluenza, coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus, procine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus, rhinovirus, measles, newcastle and adenovirus), immunosuppression (human immunodeficiency virus, reticuloendotheliosis virus), genital herpes infection (herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus), neurological infection (coxsackie B, echovirus, enterovirus), gastrointestinal infection (porcine rotavirus, rotavirus), plant infections (potato Y virus, tomato spotted wilt virus, grapevine leafroll) and other diseases (dengue virus, hepatitis A virus, vaccinia virus) (Table 1). Table 3, Table 4 summarize the possible mechanisms of action by which garlic extracts and isolated OSCs display their antiviral activity.

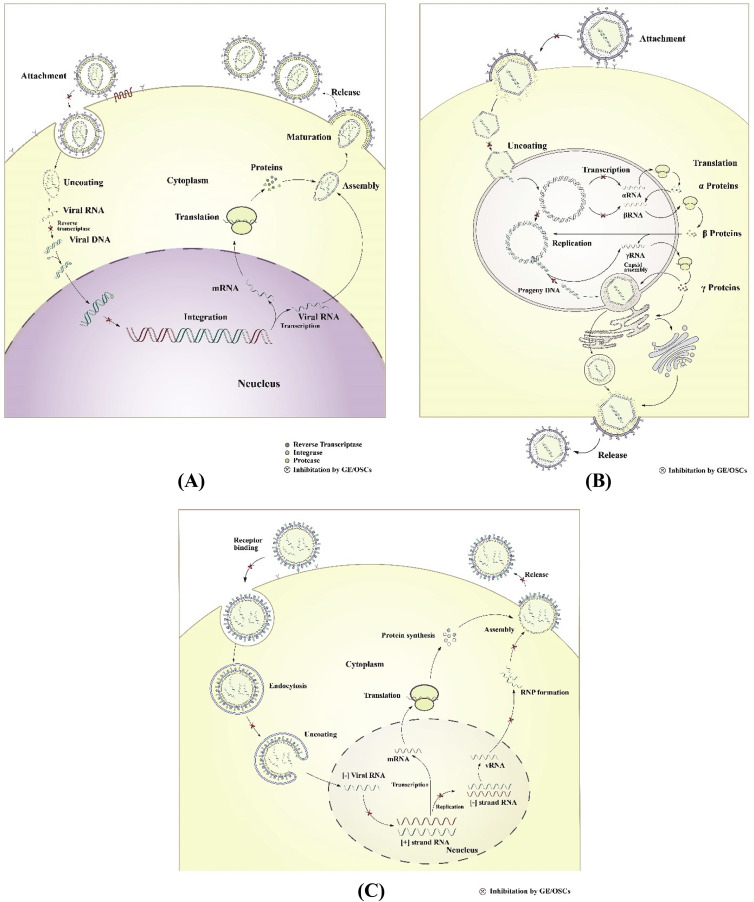

For antiviral drug discovery it is vital to understand the viral life cycle as it helps to identify therapeutic targets. A number of stages of the viral life cycle could be targeted by an antiviral drug including virus adsorption or cell entry, virus–cell fusion, virus replication (viral RNA or DNA synthesis), viral enzymes (such as neuraminidase, protease), assembly and release of virions (Fig. 2 ) (De Clercq, 2002). Sometimes host cellular enzymes (such as inosine 5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase and S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase) that have an effect on viral assembly or replication can also be targeted by antiviral agents (Story et al., 2005).

Fig. 2.

Proposed antiviral mechanism of action of garlic extract and its OSCs (GE/OSCs) in different viral life cycle. Fig. 2(A) shows the essential steps in the life cycle of “+ssRNA viruses” such as HIV-1. In this figure, GE/OSCs have shown to inhibit the entry of the virus into the host cells, inhibit the viral reverse-transcription steps i.e. block the conversion of viral RNA genome into a DNA duplex, as well as inhibition of viral integration steps. Therefore, ultimately block the viral replication and reduced cellular viral load. Fig. 2(B) shows the essential steps in the life cycle of “DNA viruses” such as HCMV or herpes virus. In this figure, GE/OSCs have shown to inhibit the entry of the virus and fusion of its genetic materials into the host cells as well as inhibit viral replication and transcription steps to block the viral replication and reduced cellular viral load. Whereas, Fig. 2(C) shows the essential steps of “-ssRNA viruses” cycle such as influenza virus. In this figure, GE/OSCs have shown to inhibit the entry and uncoating of its genetic materials into the host cells, inhibit the conversion of (−) viral RNA to (+) viral RNA steps and during the replication steps as well as assembly and release of new virions steps of their life cycle and ultimately reduced the viral load in the infected cells.

Targeting the entry or adsorption of virus to host cells by an effective entry-blocking or entry-inhibiting agent would be a potential strategy for therapeutic intervention because of easy access to the site of action, low cellular toxicity and damage, inhibition of the spread of the virus within the infected individual or lower risk to develop viral resistance to a therapy (Teissier et al., 2010). Entry into the host cell via crossing the cellular membrane is the first essential step of a viral life cycle for both enveloped (surrounded by lipid bilayer) or non-enveloped virus (bounded by proteinaceous capsid). During close contact of viruses with host cell membranes specific interactions between membrane receptors and viral envelope or capsid proteins occurre to allow virus entry into the host cell followed by a cascade of signaling steps initiating replication of the virus in the cytosol or nucleus (Thorley et al., 2010). Medicinal plants and their isolated constituents have already shown their antiviral potential by inhibiting viral entry into the host cell as a part of their mechanism of action (Lin et al., 2014). Research shows that crude GE and its OSCs exert their antiviral activity through interaction with the viral cell surface charge molecule and subsequently block or inhibit viral entry into host cells (Table 3, Table 4). Meléndez-Villanueva et al., 2019 showed that aqueous GE in gold nanoparticles (positively surface charged particles) significantly inhibit measles virus infection in VERO cells with an EC50 0.01 mg/ml (Meléndez-Villanueva et al., 2019). The virucidal activity of GE in gold nanoparticles was due to the interaction with the negatively charged viral surface receptor which blocked viral entry into the host cells (Meléndez-Villanueva et al., 2019). Aqueous GE is also active against influenza A (H1N1) viral infection in madin-darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (EC50 0.01 mg/ml) including after only a short exposure (1 h) (Mehrbod et al., 2009). Influenza virus is an enveloped virus surrounded by hemagglutinin protein that interact with sialic acid receptors on cell membrane to enter host cells (Byrd-Leotis et al., 2017). Active phytoconstituents present in the aqueous GE might be involved in the interference of viral membrane fusion by inhibiting this penetration phase in host cells (Mehrbod et al., 2009). Previously, a group of Chinese researchers showed that GE could be safe and effective against coxsackie B −3 (CVB-3) and echovirus-11 (ECHO) viral infections. They showed an GE block CVB-3 and ECHO penetration and proliferation of infected HEL and VERO cells (Luo et al., 2001). Recently, another in-vivo investigation was carried out by Harazem et al., 2019 on Newcastle Disease virus (NDV), which is an enveloped virus that can spread causing devastating diseases and severe econoic losses in the poultry industry. Harazem et al. (2019) showed that GE has the ability to prevent the attachment of NDV to the cell-receptors by destroying the virus'es envelope and ultimately block the entry of NDV into the chick embryo cells (Harazem et al., 2019). Another old study of direct viricidal activity of GE and its associated OSCs against both DNA and RNA enveloped and nonenveloped viruses (HSV-1 and 2, PIV-3, VV, VSV, and HRV-2) confirmed the antiviral potential of GE and its thiosulfinates (diallyl thiosulfinate i.e allicin, allyl methyl thiosulfinate and methyl allyl thiosulfinate) against the tested viruses (Weber et al., 1992). The results demonstrated that thiosulfinate constituents were more active (allicin; EC50 0.15–3.4 mM > allyl methyl thiosulfinate; EC50 0.37–2.9 mM > methyl allyl thiosulfinate) with lower EC50 than fresh GE (EC50 8–1000 mg/ml) (Weber et al., 1992). Both the crude extract and thiosulfinate compounds were more active against enveloped viruses (herpes simplex virus-1 and 2, parainfluenza-3, vaccinia virus, vesicular stomatitis virus) than non-enveloped virus (human rhinovirus-2) and their direct viricidal properties were due to the disruption of viral envelope and cell membrane rather than any intracellular antiviral mechanism (Fig. 2) (Weber et al., 1992). It is well stablished that OSCs, and allicin and its derivatives contribute significantly to garlics antiviral properties (Bayan et al., 2014; Sharma, 2019; Wang et al., 2017). The OSCs are highly reactive to the thiol group present in various active viral proteins or enzymes that are crucial for microbial surveillance and fusion (Ankri & Mirelman, 1999; Jain et al., 2007). During exposure to allicin or its derivatives many enzymes that contain catalytically important thiol-groups are oxidized and inhibited (Leontiev et al., 2018; Wills, 1956) which support the Weber et al., 1992 investigation of antiviral activity of allicin and its derivative with the proposed mechanisms (Weber et al., 1992). Sulfur containing compounds in garlic have also been reported to inhibit viral integrin signaling pathways to block the entry of virus into host cells (Tatarintsev et al., 1992). Integrins are transmembrane receptor proteins that respond to cell-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion or binding, and are also involved in viral entry (Giancotti & Ruoslahti, 1999). Pathogenic organisms can exploit the integrin signaling pathway to enter host cells (Dupuy & Caron, 2008). Ajoene is the sulfur containing compound isolated from garlic that possesses potent (EC50 0.045 mM) anti-HIV activity via inhibiting the integrin dependent processes to block viral adhesive interaction with host cells (Tatarintsev et al., 1992). Walder et al., 1997 showed that ajoene protected (EC50 0.0003 mM) acutely infected Molt-4 cells against HIV-1 through inhibition of virus-cell attachment on host cells (Fig. 2A) (Walder et al., 1997). Another study demonstrated that a non-organosulfur proteinous compound, a lectin, derived from garlic, showed antiviral activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) via inhibition of early viral attachment and inhibitory activity at the end of the infectious virus cycle (Keyaerts et al., 2007).

Inhibition of viral replication is another potential target for chemotherapeutic intervention. The effectiveness of viral replication inhibitors is dependent on their impact on viral protein synthesis, reverse transcription, viral DNA polymerization, enzymatic reactions involved in viral DNA or RNA synthesis and viral integration into host cells (Clercq, 2001). Some other inhibitors also block viral release into the host cell as a fusion inhibitors to prevent viral replication (Lorizate & Kräusslich, 2011). Most RNA and DNA viruses replicate in the host cell cytoplasm or in the nucleus, respectively. An advantage of inhibiting the viral replication is the specificity to infected cells rather than normal cells (Desselberger, 1995). Natural products have been reported to inhibit viral replication for a wide range of viruses (Oliveira et al., 2017; Said & Abdelwahab, 2013). Garlic and its constituents have been reported to exert antiviral effects by inhibiting viral replication against a number of pathogenic viruses. Mehrbood et al., 2013 showed that fresh GE inhibits the viral replication by blocking the formation of influenza A virus antigens even at an very early stage of infection of MDCK cells. Virus load in the infected cells was also reduced (Mehrbod et al., 2013). Pre- and post-treatment of NDV with ethanolic GE showed a dose dependent prevention of infection in VERO cells (EC50 0.025 mg/ml). Researchers believe that the infection prevention was due to the inhibition of viral fusion to VERO cells due to the blockage of cell surface receptors important for virus integration into host cells (Mehmood et al., 2018). These cell surface receptors are glycoproteins or glycolipids that facilitate the viral fusion through interaction with hemagglutinin protein of the viral cell surface (Chang et al., 2011). Another study conducted by Chavan et al., 2016 evaluated the anti-influenza A activity of co- and posttreatment of ethanolic GE in infected MDCK cells using a hemagglutination assay. Post-exposure treatment revealed that the anti-influenza activity of the GE extracts might be due to the inhibition of virus replication or blocking virus budding from the infected MDCK cells (Fig. 2C) (Chavan et al., 2016). The authors proposed that this activity might be due to allicin induced inhibition of viral RNA polymerase, because its ability to react with thiol groups of different viral enzymes including RNA polymerase (Ankri & Mirelman, 1999). A similar study was conducted by Mohajer Shoji et al. (2016) which showed for the first time antiviral effects (co-treatment and post-treatment) of aqueous GE against coronavirus (Mohajer Shojai et al., 2016). Coronavirus is a causative agent of severe infections in poultry, and can in its modified form cause severe acute respiratory syndromes including SARS, MERS and COVID-19. The results of both co-treatment and post exposure of aqueous GE on corona infected embryonic eggs showed significant increase of the embryonic index which suggests that GE could have an inhibitory effect on virus replication, however, no mechanism of action was specified (Mohajer Shojai et al., 2016).

Reverse transcription is one of the essential steps in the retrovirus family (Retroviridae) replication process to convert the virus RNA to DNA using the reverse transcriptase (RT) (Hu & Hughes, 2012). The RT enzyme has become a very significant therapeutic target with a number of specific inhibitors designed to suppress viral growth and infection. The discovery of more RT inhibitors is of great importance, because of increased viral resistance to current treatment (Miceli et al., 2012). Although a number of natural products and traditional medicines have shown activity against a variety of viral infections including retrovirus (such as HIV), only a very few of them are active against the RT (Kun Silprasit et al., 2011). Interestingly, the n-hexane extract of fresh garlic has been reported to have inhibitory activity against HIV-1 RT with an EC50 0.06 mg/ml, ultimately inhibiting the replication of HIV in host cells (Fig. 2A) (Kun Silprasit et al., 2011). The OSCs in garlic have been described as possessing anti-HIV activity through the inhibition of viral replication in a number of studies. For example, it has been shown that synthetic ajoene can significantly protect acutely HIV-1 infected Molt-4 cells (EC50 0.0003 mM) by inhibiting HIV-1 replication through the inhibition of HIV-1 RT (Fig. 2A) (Walder et al., 1997). In addition, garlicin was reported to inhibit HIV-1 replication in the experiment using HIV-1 producing CEM/LAV-1 cell line with an EC50 0.03 mM (Shoji et al., 1993). The mechanism by which garlicin inhibits the replication of HIV-1 is not clear but it has been proposed that garlicin, being a thiol compound, inhibits phorbol ester stimulated HIV-1 replication or inhibits ‘HIV-1 tat’, a transactivator protein of HIV-1 replication, similar to other thiol compounds (N-acetyl-l-cysteine and 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanol) (Kubota et al., 1990; Roederer et al., 1990; Shoji et al., 1993). There was no report found on allicin ability to inhibit HIV, but a recent study reported that allicin can inhibit replication of reticuloendotheliosis virus (REV) and alleviates the infection in chicken (Wang et al., 2017). REV is a retrovirus in the Retroviridae family and causes an immunosuppressive syndrome in different avian hosts. The study conducted by Wang et al., 2017 showed, that allicin inhibited REV replication by suppressing the activation of ERK in lymphocytes and spleen of avian hosts. In the thymus of REV-infected chickens the phosphorylation of p38, ERK, and JNK was downregulated (Wang et al., 2017). The results suggest that allicin has the ability to inhibitREV replication via a downregulation of the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2017).

Allitridin is another active OSC of garlic. A number of in-vitro and in-vivo studies have reporting on its potent inhibitory activity towards human cytomegalovirus (HCMV). It is well known that immediate-early genes (IEGs) upregulation in HCMV plays a significant role in the regulation of its transcription as well as replication (Fig. 2B) (Gibson, 1994). A study on the anti-HCMV activity of allitridin demonstrated that it inhibits HCMV's early stage replication irrespectively of strains in both, in HEL cells and in MCMV-induced mice (Fang et al., 1999). The inhibition of HCMV IEGs by allitridin was further validated in-vitro by Zhen et al., 2006 and Shu et al., 2003. They showed that allitridin can inhibit the early phase of HCMV replication, even before viral DNA synthesis, in a dose-dependent manner (EC50 0.02 mM), and that the mechanism is linked to the suppression of ‘IEG1’ transcription (Shu et al., 2003; Zhen et al., 2006). Another study evaluating the pre- and post-treatment (2 days) efficacy of allitridin in MCMV-induced hepatitis of immunosuppressed mice (ref) showed, that viral load in liver, level of plasma alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or histological lesion in mice liver was significantly reduced pre- and post-treatment indicatinga possible therapeutic efficacy of allitribin in MCMV hepatitis (Liu et al., 2004).

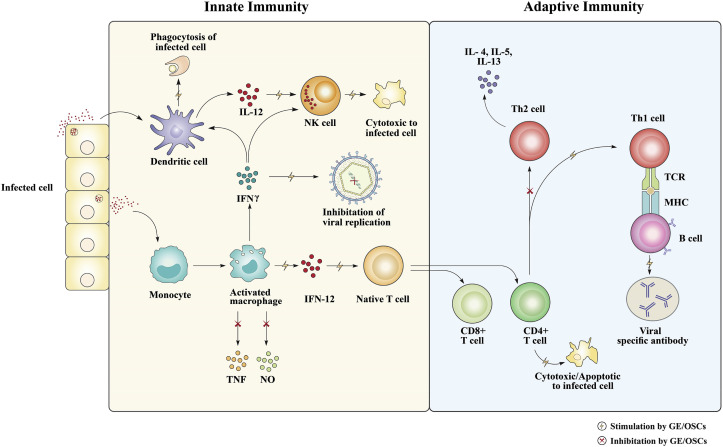

Following an acute viral infection, the host immune system tries to clear the virus quickly through killing the infected cells or the release of cellular proinflammatory cytokines (Oldstone, 2009). These immune responses comprise of an initial innate immune response (killing or eliminating infected cells) via macrophages, NK cells or dendritic cells and then elevation of adaptive immunity via T and B cells (antigen-specific response to kill infected cells and release inflammatory cytokines to inhibit viral replication) (Fig. 3 ) (McGill et al., 2009; Oldstone, 2009). Several reports have highlighted immunomodulatory properties of natural products or plant extracts. These activities play a crucial role in the alleviation of viral infection, the regulation of viral replication, decrease of viral spreading and viral load (Ganjhu et al., 2015). Immunomodulating activity of natural products and plant extracts are exhibited through the induction of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, 12), the activation of the innate immune response (activation of macrophases and dendritic cells), as well as through elevation of adaptive immunity (enhance CD + cells, T cells activity) (Ganjhu et al., 2015; Trinchieri, 2003). Garlic has been reported to possesses immunomodulating properties in a number of in-vitro and in-vivo studies. The organosulfur compounds seem to be the main garlic constituents responsible for these effects. (Venkatesh, 2018). Other constituents such as lectins and water-soluble fructans (polysaccharide) have also shown immunomodulating potential (Li et al., 2017). Research shows that GE and its OSCs have immune enhancing activities to prevent different viral infections both in-vitro and in-vivo (Guo et al., 1993; Liu et al., 2013). Liu et al. (2013) demonstrated that dietary supplementation of GE can improve both, innate and adaptive immunity, as well as growth efficiency of PRRSV-infected weaned pigs due to immunomodulating effects of GE through increasing of CD8+ T and B cells, antibody titers, anti-inflammatory cytokines and haptoglobin (Hp) in infected pigs (Liu et al., 2013) (Fig. 3). The immunomodulatory effect of GE was also shown against HCMV infection in-vitro with its prophylactic use suggested in immunocompromised patients (Guo et al., 1993). A preclinical study of allitridin, an OSC of garlic, in cytomegalovirus induced infection of BALB/c mouse, showed that the innate and specific cellular responses to clear CMV from infected mice are achieved via up-regulation of Th1 specific transcription factor T-bet mRNA (increase Th1 cytokine IFN-γ secretion) and down-regulation of GATA-3 mRNA (i.e reduce Th2 cytokine IL-10 secretion) (Yi et al., 2005)). Another preclinical study in mice confirmed that CMV might modulate cellular Treg functions to escape the host immune surveillance for causing acute or chronic infection (Li et al., 2013). CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) play an important role in downregulating the immune response by inhibiting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells proliferation and activation, as well as reduction of cytokine secretion (Schmidt et al., 2012). Allitridin demonstrated potential anti-CMV activity via promoting CMV-induced Treg expansion and Treg-mediated anti-MCMV immunosuppression in-vivo (Li et al., 2013). Ajoene, another principle constituent of garlic, formed from heating of crushed garlic possesses potential immunostimulant activity that showed HCMV-induced anti-tumor activity via immune recognition of tumor-specific T cells and their apoptosis by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Terrasson et al., 2007). Viral-mediated CD4+ T-cell destruction is progressive pathogenesis of impairment of immunity of early HIV infection (Okoye & Picker, 2013). A number of reports showed that pure ajoene can protect CD+ cells destruction from HIV attack as part of its immunomodulatory mechanism to prevent HIV infection (“Garlic extract for HIV?", 1998; Walder et al., 1997). Molecular docking study of ajoene found that it can potentially bind with HIV-1 protein which also supports its anti-HIV activity (Gökalp, 2018).

Fig. 3.

Proposed mechanism of immunomodulatory effect of garlic and its OSCs in viral infected host. In the figure, the mechanism of immunomodulatory activity of garlic and its OSCs shown to involve in the elevation of innate immune response via macrophage and natural killer (NK) cells as well as enhancing adaptive immunity through T cells and B cells.

OSCs have also shown anti-inflammatory activities including in viral infections. Dengue virus (DENV) infection-initiated inflammation is an important host immune response. It causes pathogenicity via the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines leading to vascular leakage and endothelial permeability (Hall et al., 2017). It is reported that oxidative stress has a crucial role in triggering inflammation (Olagnier et al., 2014). In case of DENV infection induced oxidative stress has also been reported to link to the development of inflammation and the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Seet et al., 2009; Soundravally et al., 2008). As such the alleviation of oxidative stress, as well as inflammation, are possible strategies for the treatment of Dengue Fever. Interestingly, OSCs from garlic such as allilin, garlicin and diallyl sulfide, reduced DENV induced oxidative stress and inflammation in-vitro (Fig. 3) (Hall et al., 2017). Other reports also show that allicin is able to alleviate oxidative damage and inflammation caused by REV infection in an in-vivo model (Wang et al., 2017). An immune enhancing effect of garlic was also confirmed in a randomized clinical trial with 17 volunteers who had a garlic-free or garlic-containing meal for 10 days. The trial showed that garlic can upregulate immune response genes and activate apoptosis and the xenobiotic metabolism in people who regularly consume garlic containing meals (Charron et al., 2015). The anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory potential of garlic was also subject to a most recent publication indicating that garlic may be beneficial as a preventive measure in the current COVID-19 pandemic (Donma & Donma, 2020).

3.2. Clinical studies of garlic and its organosulfur compounds against viral infection

Pre-clinical studies of garlic and its OSCs show to have antiviral activity against a number of viral infections. Research data show that a large number of preclinical antiviral studies of garlic have examined its effect against viruses that cause flu and respiratory infections including influenza, parainfluenza, coronavirus, SARS-CoV, PRRSV, rhinovirus, MeV, NDV and adenovirus (Table 1). The increasing number of pre-clinical studies on this topic indicates the necessity to optimize garlic's clinical evaluation. A number of clinical trials have shown antiviral effects of garlic against viral cold and flu infections (Hiltunen et al., 2007; Josling, 2001; Nantz et al., 2012; Percival, 2016), acute respiratory viral infections (Andrianova et al., 2003) and immune actions against recalcitrant multiple common warts (RMCW) (Kenawy et al., 2014; Mousavi et al., 2018) (Table 5).

Josling et al., 2001 was the first to report on a clinical trial with garlic that showed prevention of the common cold (Josling, 2001). The trial included 146 volunteers (mean age 52 yrs), divided into two groups, placebo and active, who took a180 mg allicin containing garlic capsule (one capsule/day) over 84 days. (Table 5). At the end of the trial, including an extra week of follow up, the active group showed significantly fewer and shorter incidences of the cold than the placebo group. Viral re-infection was also higher in the placebo group than active group (Josling, 2001). The results of this study suggest that the reduction of viral infection and reinfection can be decreased through daily garlic supplementation. This may be due to garlic's, specifically allicin's, immunomodulating effects which have been shown in preclinical studies (“Garlic extract for HIV?", 1998; Li et al., 2017; Walder et al., 1997).

Another randomized double-blinded controlled trial tested powdered garlic extract (PGE) as a cellulose formulation to see whether it prevented airborne infection in 52 frequent travelers (26 in each group, garlic formulation vs. cellulose only, average age 38 yrs). The groups were instructed to take one sniff in each nostril every day for 56 days, and during infection up to 3 sniffs per nostril/day. Health and infection episodes were recorded in a daily diary. There were significantly fewer and shorter periods of infections observed in the group treated with PGE, and PGE group participants were less likely to be infected with an airborne pathogen when PGE was taken (Hiltunen et al., 2007). The mechanism of airborne infection prevention was not explained, but it might be due to garlic's antiviral and immunomodulatory effects as noted in preclinical studies.

Around the same time of the first clinical trial with garlic, a Russian group Andrianova et al., 2003 conducted a randomized two stage clinical trial in children using a commercial, sustained release garlic extract (SRGE) tablet. The trial investigated whether this formulation can prevent acute respiratory viral infection (ARVI) compared to benzimidazole (Andrianova et al., 2003). The initial stage of the trial was looking at the effect of SRGE tablet (600 mg GE tablet/day for 150 days) on tolerance and ARVI morbidity in 172 children (mean average age 7–16 yrs) compared to 468 controls (placebo only). The second stage of the trial evaluated the effects of SRGE tablet (300 mg/day for 150 days) on ARVI morbidity among 42 children compared with 41 control and 73 benzimidazole-treated children (age 10–12 yrs). The SRGE tablet did not show any adverse effects and reduced morbidity of ARVI in children by 2–4 fold compared to placebo. In the second stage of the trial, at a lower dose ARVI morbidity was reduced by about 1.7-fold compared to placebo and 2.4-fold compared to benzimidazole. The highlights that garlic products can play a role in the prevention of non-specific ARVI in children (Andrianova et al., 2003).

Garlic are immune modulators and reports suggest dietary meal containing garlic (raw or crushed) can influence the expression of immunity in humans (Abdullah, 2000; (Charron et al., 2015). A recent clinical trial has shown that diet supplemented with aged garlic extract (AGE) can modulate the inflammation and immunity of adults with obesity (Xu et al., 2018). With the question in mind whether GE supplementation can modify the immunity in humans and protect from colds and flu, Nantz et al., 2012 conducted a double-blind randomized clinical trial with 120 subjects, with a mean age 26 yrs (Nantz et al., 2012). The active group (n = 60) took one AGE capsule (2.56 g/cap)/day for 90 days and the placebo group (n = 60) took also 1 capsule/day. The trial looked at the reduction of severity of cold and flu, days of symptoms, number of incidences and work/school missed, as well as at specific innate-like lymphocytes (γδ-T cell and NK cell) and antioxidant levels (Table 5). The group consuming the AGE capsule showed significantly reduced cold and flu severity, number of days and incidences of illness and number of work/school days missed due to illness compared to placebo group (Nantz et al., 2012). The biochemical analysis demonstrated significant proliferation of γδ-T cells and NK cells, serum antioxidant concentration (SAC), cytosolic GSH and reduction of inflammatory cytokines secretion in the group of consuming AGE suggesting that AGE supplementation in the diet can enhance immune response and may be responsible for alleviation of severity of the common cold and flu. This study was adapted well as an explanation of molecular mechanism of protective effect of GE against common cold and flu (Andrianova et al., 2003; Hiltunen et al., 2007; Josling, 2001).

Garlic and its OSCs have shown to prevent viral induced hepatitis in a number of preclinical studies (Table 3, Table 4). One randomized double blinded clinical trial was found that looked at the hepatoprotective effects, safety and tolerability of an oral capsule containing garlic oil (GO) with dimethyl-4,4′-dimethoxy-5,6,5′,6′-dimethylene dioxybiphenyl-2,2′-dicarboxylate (DDB) in chronic hepatitis patients (Lee et al., 2012). The study with 88 subjects of chronic hepatitis (HBV or HCV) contained four parallel groups (20 in each) including one placebo group and three escalating dose groups of 25 mg DDB plus 50 mg GO (two cap/day; three cap/day and six cap/day) for 42 days with extra 7 days follow-up. Efficacy was evaluated by examining the changes in serum ALT and AST as markers for HBV or HCV hepatitis induced liver injury by. After 6 weeks of treatment with six cap/day of DDB plus GO serum aminotransferase levels in chronic hepatitis patients induced by HBV or HCV viruses were significantly reduced with no clinical adverse effects and biomarker abnormalities (Lee et al., 2012). These results confirm previous research that indicated that pretreatment of GO and DDB can protect chemical-induced liver injury by elevating GSH level as well as lowering serum lipid levels (Park et al., 2005).

The RMCW is a consequence of an infection of warts virus human papillomavirus (HPV) (Lipke, 2006). To date no simple and easy treatment that eradicates RMCW exists, although it seems that treatment of warts by intralesional immunotherapy is effective, (Horn et al., 2005). Kenawy et al., 2014 investigated whether lipid garlic extract (LGE) can be used for the eradication of RMCW due to garlic's immunomodulatory activity (Kenawy et al., 2014). The study (n = 50) was conducted in two parallel groups including an active group (M = 6, F = 19) and placebo group (M = 20, F = 5) with a mean average age 25+ yrs. The active group applied LGE to the largest one of RMCW twice per day for 28 days, whereas, placebo group participants applied saline twice a day for 28 days. Efficacy of LGE on RMCW was evaluated by its effect on RMCW to decrease in size of warts using photographic comparison with placebo. The response was considered either as complete (complete disappearance), partial (reduced size in 25%–100%) or no response (0–25% decrease in size). Serum TNF-α (0 and 4th week) and adverse effects for up to 6 months were also recorded Interestingly, a significant number of patients (92%) showed complete eradication of RMCW in the LGE group compared to placebo participants (only 4%) after 4-weeks of treatment with no adverse effect at the 6-months follow-up (Kenawy et al., 2014). However, there was no statistically significant difference in serum TNF-α level in both groups. Although, it is reported that the immunotherapy is associated with a stimulation of immune response against HPV (mediated by different cytokines), the results indicated wart regression might be associated with indirect immunomodulation, as well as an interplay between different cytokines other than TNF-α (Kenawy et al., 2014). Garlic extract proved to be effective in the complete eradication of cutaneous warts (Lipke, 2006) and recently Mousavi et al., 2018 conducted another RCT to evaluate the effect of garlic compared with cryotherapy (liquid nitrogen) on male genital warts. Both groups, the cryotherapy and active group (10% garlic extract) consisted of 33 men who all had at least one genital wart on both sides of the genital region. GE (10%) was applied on the left side warts and cryotherapy (on right side warts for 56 days (Mousavi et al., 2018). Significant complete eradication of male genital warts (about 70%) was observed in the active (10% GE) group with results being comparable to cryotherapy (78% eradication). The molecular mechanism of the effect of garlic against genital warts is not clear, but a number of mechanisms have been proposed including garlic induced enhancement of immunity and cellular function, antiviral effect of garlic and a garlic induced increase in serum GSH (Mousavi et al., 2018).

4. Conclusion and perspectives

Viral infections are a leading global challenge due to the increase in viral drug resistance and rapid mutations. Plants, as a natural medicine, have a long history of use against infectious diseases and as a potential source of novel drug discovery. Garlic has been used widely for thousands of years as a functional food and a spice as well as a traditional medicine against a number of diseases including infections. Allicin and its derivatives, ajoene, allitridin and garlicin, were found to be the most promising OSCs of garlic and are responsible for several of garlic's therapeutic activities including the prevention of viral infections. Consumption of fresh, cooked and supplemented garlic are well tolerated at a reasonable level in or with a meal and regarded as safe by the FDA. Studies conducted in in-vivo and in-vitro test models clearly demonstrate antiviral potential of garlic and its OSCs against a wide range of viruses; for example from the Adenoviridae, Arteriviridae, Coronaviridae, Flaviviridae, Flaviviridae, Herpesviridae, Orthomyxoviridae, Picornaviridae, Paramyxoviridae, Poxvirus, Rhabdoviridae and Retroviridae family. The present review gives insight into the antiviral effects of garlic and its OSCs in pre-clinical and clinical studies, and highlights the variety of mechanisms through which these effects are achieved. Blocking viral entry and fusion into host cells, inhibiting viral RNA polymerase, reverse transcriptase, and viral replication, as well as enhancing host immune response were the major pathways for antiviral activity of garlic and its OSCs. Immunomodulatory activity was shown to elevate the innate immune response via macrophage and NK cells, as well as enhance adaptive immunity through T cells, B cells and anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Randomized clinical trials utilizing a variety of commercial garlic preparations revealed a prophylactic effect of garlic in the prevention and treatment of a number of viral infections in human including the common cold and flu, viral induced hepatitis and warts. Improved immune response was claimed to be responsible for these effects. Thus the literature review highlights the antiviral potential of garlic and its various OSC's, their possible therapeutic use in the prevention of viral infections, as well as in antiviral drug development. However, more high quality, clinical research, including long-term cohort studies and pharmacokinetic investigations need to be conducted to further elucidate garlic's and its OSCs role in antiviral therapy.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgement

The author would like to thank Prof. Hossain for his valuable comments and feedback on the primary version of the manuscript.

References

- Abad J.A., Moyer J.W., Kennedy G.G., Holmes G.A., Cubeta M.A. Tomato spotted wilt virus on potato in eastern North Carolina. American Journal of Potato Research. 2005;82(3):255. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah T. A strategic call to utilize Echinacea-garlic in flu-cold seasons. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2000;92(1):48–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abiy E., Asefaw B. Anti-bacterial effect of garlic (Allium sativum) against clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli from patients attending Hawassa Referral Hospital, Ethiopia. Journal of Infectious Diseases and Treatment. 2016;2(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Al Abbasi A. Efficacy of garlic oil in treatment of active chronic suppurative otitis media. Kufa Medical Journal. 2008;11:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ballawi Z., Redhwan N., Ali M. In-vitro studies of some medicinal plants extracts for antiviral activity against rotavirus. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy and Biological Sciences. 2017;12:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Alejandria M.M. Dengue haemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome in children. BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2015 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkowni R., Zhang Y.-P., Rowhani A., Uyemoto J.K., Minafra A. Biological, molecular, and serological studies of a novel strain of grapevine leafroll-associated virus 2. Virus Genes. 2011;43(1):102–110. doi: 10.1007/s11262-011-0607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagase H. Clarifying the real bioactive constituents of garlic. Journal of Nutrition. 2006;136(3 Suppl):716s–725s. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.3.716S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrianova I.V., Sobenin I.A., Sereda E.V., Borodina L.I., Studenikin M.I. Effect of long-acting garlic tablets "allicor" on the incidence of acute respiratory viral infections in children. Terapevticheskii Arkhiv. 2003;75(3):53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankri S., Mirelman D. Antimicrobial properties of allicin from garlic. Microbes and Infection. 1999;1(2):125–129. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arreola R., Quintero-Fabián S., López-Roa R.I., Flores-Gutiérrez E.O., Reyes-Grajeda J.P., Carrera-Quintanar L., Ortuño-Sahagún D. Immunomodulation and anti-inflammatory effects of garlic compounds. Journal of Immunology Research. 2015:401630. doi: 10.1155/2015/401630. 2015, 401630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz E., Alpsoy H.C. Garlic (Allium sativum) and traditional medicine. Turkiye Parazitoloji Dergisi. 2007;31(2):145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayan L., Koulivand P.H., Gorji A. Garlic: A review of potential therapeutic effects. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 2014;4(1):1–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borlinghaus J., Albrecht F., Gruhlke M.C.H., Nwachukwu I.D., Slusarenko A.J. Allicin: Chemistry and biological properties. Molecules. 2014;19(8):12591–12618. doi: 10.3390/molecules190812591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brace L.D. Cardiovascular benefits of garlic (Allium sativum L) Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2002;16(4):33–49. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd-Leotis L., Cummings R.D., Steinhauer D.A. The interplay between the host receptor and influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(7):1541. doi: 10.3390/ijms18071541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T.-T., Sun M.-F., Chen H.-Y., Tsai F.-J., Chen C.Y.-C. Drug design for hemagglutinin: Screening and molecular dynamics from traditional Chinese medicine database. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers. 2011;42(4):563–571. [Google Scholar]

- Charron C.S., Dawson H.D., Albaugh G.P., Solverson P.M., Vinyard B.T., Solano-Aguilar G.I., Novotny J.A. A single meal containing raw, crushed garlic influences expression of immunity and cancer related genes in whole blood of humans. Journal Of Nutrition. 2015;145(11):2448–2455. doi: 10.3945/jn.115.215392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavan R.D., Shinde P., Girkar K., Madage R., Chowdhary A. Assessment of anti-influenza activity and hemagglutination inhibition of Plumbago indica and Allium sativum extracts. Pharmacognosy Research. 2016;8(2):105–111. doi: 10.4103/0974-8490.172562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.-H., Chou T.-W., Cheng L.-H., Ho C.-W. In-vitro anti-adenoviral activity of five Allium plants. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers. 2011;42(2):228–232. [Google Scholar]

- Choi H.-J. Chemical constituents of essential oils possessing anti-influenza A/WS/33 virus activity. Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives. 2018;9(6):348–353. doi: 10.24171/j.phrp.2018.9.6.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clercq E. Molecular targets for antiviral agents. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford S.E., Ramani S., Tate J.E., Parashar U.D., Svensson L., Hagbom M.…Estes M.K. Rotavirus infection. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers. 2017;3:17083. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.83. 17083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalldorf G., Gifford R. Clinical and epidemiologic observations of Coxsackie-virus infection. New England Journal of Medicine. 1951;244(23):868–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195106072442302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq E. Strategies in the design of antiviral drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2002;1(1):13–25. doi: 10.1038/nrd703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desselberger U. In: Medical virology: A practical approach. Desselberger U., editor. Oxford University Press; New York: 1995. Molecular epidermiology; pp. 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dietze K., Pinto J., Wainwright S., Hamilton C., Khomenko S.… . Focun on. Vol. 5. 2011. Porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS): Virulence jumps and persistent circulation in southeast asia; p. 8. (Food and agricutural organizations of the United States). Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Donma M.M., Donma O. The effects of allium sativum on immunity within the scope of COVID-19 infection. Medical Hypotheses. 2020;144:109934. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy A.G., Caron E. Integrin-dependent phagocytosis – spreading from microadhesion to new concepts. Journal of Cell Science. 2008;121(11):1773. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Saber B.G., Magdy B.A., Wasef L.G., Elewa Y.H.A., AAl-Sagan A., Abd El-Hack M.E., Prasad Devkota H. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of garlic (Allium sativum L.): A review. Nutrients. 2020;12(3):872. doi: 10.3390/nu12030872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]