Abstract

Cancer is still a severe health problem globally. The therapy of cancer traditionally involves the use of radiotherapy or anticancer drugs to kill cancer cells, but these methods are quite expensive and have side effects, which will cause great harm to patients. With the find of anticancer peptides (ACPs), significant progress has been achieved in the therapy of tumors. Therefore, it is invaluable to accurately identify anticancer peptides. Although biochemical experiments can solve this work, this method is expensive and time-consuming. To promote the application of anticancer peptides in cancer therapy, machine learning can be used to recognize anticancer peptides by extracting the feature vectors of anticancer peptides. Nevertheless, poor performance usually be found in training the machine learning model to utilizing high-dimensional features in practice. In order to solve the above job, this paper put forward a 19-dimensional feature model based on anticancer peptide sequences, which has lower dimensionality and better performance than some existing methods. In addition, this paper also separated a model with a low number of dimensions and acceptable performance. The few features identified in this study may represent the important features of anticancer peptides.

Keywords: anticancer peptide, feature extraction, feature model, feature selection, machine learning

Introduction

Cancer is still a severe health problem globally, and lots of people have died from cancer (Liao et al., 2018; Cheng et al., 2019a; Zeng W. et al., 2019; Zhang Y. et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020). Traditional cancer treatments kill not only cancer cells but also normal cells, and the medical costs are very high (Feng, 2019; Lin et al., 2019; Li Y.H. et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). With the find of anticancer peptides, the situation has changed because anticancer peptides can interact with the anionic cellular elements of cancer cells to selectively kill cancer cells without harming the normal cells of the body (Ozkan et al., 2019; Wang Y. et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2020). Although there have been some defects in the development of anticancer peptides, anticancer peptides are safer than man-made drugs (Sun et al., 2016; Liu H. et al., 2018; Liao and Jiang, 2019; Munir et al., 2019; Srivastava et al., 2019; Liu H. et al., 2020; Ru et al., 2020; Wang J. et al., 2020) and have higher effectiveness, specificity and selectivity. Anticancer peptides provide a new direction for the treatment of cancer, so the therapeutic methods of anticancer peptides have attracted greater attention. Anticancer peptides are generally composed of five to thirty amino acids. Nevertheless, it is still hard to identify anticancer peptides from other (artificially designed or natural) peptides. Using biochemical experiments to identify anticancer peptides is very time-consuming and expensive. In addition, only a few anticancer peptides can be used in the clinic. Thus, it is essential to apply machine learning to forecast anticancer peptides.

In past few years, some bioinformatics methods have been introduced to predict anticancer peptides. By extracting the amino acid composition and binary features of anticancer peptides as feature vectors, Tyagi et al. (2013) applied support vector machine to verify the performance, and the accuracy reached 91.44%. Hajisharifi et al. (2014) applied support vector machine to predict anticancer peptides on the basis of the local alignment kernel and pseudo-amino acid composition, and the highest accuracy was 89.7%. Chen W. et al. (2016) developed a classifier for predicting anticancer peptides by optimizing the composition of g-GAP dipeptides, and 94.77% accuracy was obtained by using 126D features. Xu et al. (2018b) used 400D features or 400D-g gap features to predict anticancer peptides, and the accuracy of support vector machine reached 91.86%. The above methods obtained sound prediction results, but these methods did not mention the dimensional advantages of the model. In reality, training the machine learning model utilizing high-dimensional features usually behaves poorly, This phenomenon is called Curse of Dimensionality (Wilcox, 1961; Xu et al., 2017; Xu Y. et al., 2018; Zou et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019).

In this paper, through using a variety of polypeptide feature extraction methods, the obtained feature vectors were selected many times, which gained a low-dimensional model. Using multiple classifiers for verification, the performance accuracy was 92.73%, while the number of dimensions of the model was only 19. In this paper, the most important 7 dimensional features were further separated and verified, and good results were obtained. The feature model obtained in this paper can not only accurately and rapidly classify anticancer peptides, but also effectively avoid Curse of Dimensionality. The above results may suggest that these low-dimensional features are important features for distinguishing anticancer peptides.

Materials and Methods

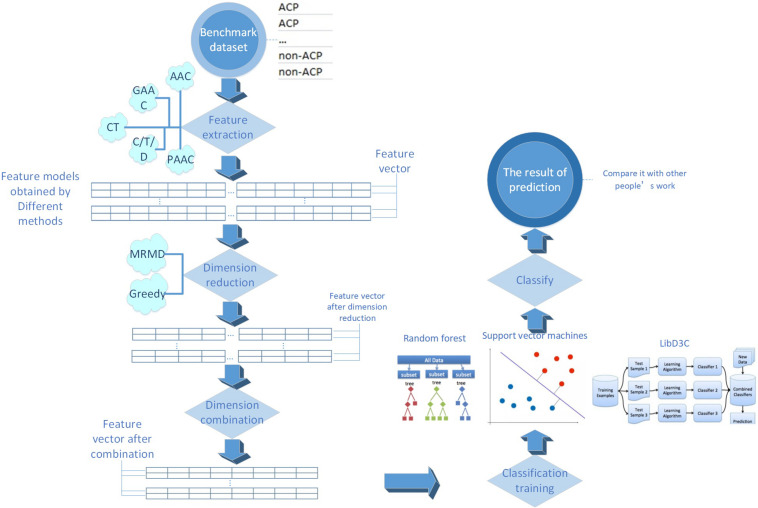

The process of this research is shown in Figure 1. Every detailed step will be presented in the following sections.

FIGURE 1.

The main flow chart of the research process in this paper.

Benchmark Dataset

In this paper, we used the benchmark dataset constructed by Hajisharifi et al., which contained 206 non-anticancer peptides and 138 anticancer peptides. The anticancer peptides in this data set were extracted from APD2, and 206 non-anticancer peptides established by Wang et al. were extracted from UniProt. To avoid the deviation of the classifier, peptides with more than 90% similarity were deleted from the data set through CD-HIT. Chen et al. and Xu et al. have applied the identical benchmark data set as well.

Feature Extraction Strategies

The peptide sequences can not be immediately identified by machine learning algorithms. Therefore, it is requisite to translate the strings stood for peptide sequences into numerical features (Liu et al., 2006, 2019b; Liu S. et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Chen C. et al., 2019; Hong J. et al., 2019). The feature extraction methods are very crucial in building computational predictors (Cheng et al., 2018, 2019b; Xiong et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018b,2019a; Sun et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2019).

In this paper, we applied five sorts of feature extraction strategies including amino acid composition (AAC), conjoint triad (CT), pseudo-amino acid composition (PAAC), grouped amino acid composition (GAAC) and C/T/D. Each strategy may also include several feature extraction methods. This paper implemented these strategies through iFeature (Chen et al., 2018).

Conjoint Triad

Shen et al. (2007) put forward the conjoint triad model (CT). In consideration of the properties of one amino acid and its nearby amino acids and regards any three sequential amino acids as a unit, the model classifies amino acids into seven sorts. Triad in the same class are considered similar. As an example, triads which are composed by three amino acids belonging to the same sort, such as GLM and VFT, could be treated equally, since they may play the same role. A peptide sequence is represented by a binary space (V,F). V is the vector space of sequence features. Each feature (vi) represents a unit. F is the frequency vector corresponding to V, and each feature (fi) is the frequency of vi in a peptide sequence.

C/T/D

Dubchak et al. (1995) put forward the C/T/D model. This model considers 3 properties of amino acids, their solubility, secondary structure and relative hydrophobicity. Amino acids are classified into three classes on the basis of the relative hydrophobicity, three or four classes on the basis of the secondary structure, and two classes on the basis of solubility. Each class is presented by the three kinds of descriptors: C/T/D (Tan et al., 2019).

Amino Acid Composition

The peptide is composed of 20 sorts of amino acids (Liu et al., 2019a). The frequency of every amino acid type in a peptide sequence was computed to present the peptide sequences. Therefore, each peptide sequence can be represented as a 20-dimensional feature model. This model is called amino acid composition model (AAC). The features can be defined as:

where Na is the quantity of amino acid type a. while N is the length of a peptide sequence.

In this paper, we also used the k-spaced amino acid pair composition model (CKSAAP), which computes the frequency of amino acid pairs separated by an arbitrary number (k) of amino acid residues. A example of this encoding scheme (k = 0) is provided as follow:

The features (k = 0) can be defined as:

At the same time, this paper used the tripeptide composition model (TPC), which computes the frequency of three consecutive amino acids in a peptide sequence and provides 8000 dimensional features. The features can be defined as:

where Nabc is the quantity of amino acid type a, b, and c. while N is the length of a peptide sequence.

At the same time, this paper used the dipeptide composition model (DPC), which computes the frequency of two consecutive amino acids in a peptide sequence and provides 400D features. The features can be defined as:

where Nab is the quantity of amino acid type a and b. while N is the length of a peptide sequence.

Pseudo-Amino Acid Composition

Chou (2001) put forward a pseudo-amino acid composition model (PAAC). In this model, It takes into account not only the frequency of each amino acid type in a peptide sequence but also the position information of the amino acids. Therefore, the feature of the pseudo-amino acid composition is stated as below:

PAAC = (a1,a2,…,a19,a20,a20+1, a20+2,…,a20+n)

The front portion a1,…, a19,a20 stand for the frequency of each amino acid type in a peptide sequence, and the latter portion a20+1,…,a20+n represent the location info of the amino acids in a peptide sequence.

This paper also used a method similar to PAAC. The amphiphilic pseudo-amino acid composition model (APAAC) was put forward by Chou et al. The model takes the hydrophilic and hydrophobic properties of amino acids into account.

Grouped Amino Acid Composition

The grouped amino acid composition model (GAAC) divides 20 amino acid types into 5 classes on the basis of the physical and chemical properties and then computes the frequency of each amino acid group in a peptide sequence. The features can be defined as:

where Nc is the quantity of amino acid in class c. while N is the length of a peptide sequence.

In this paper, a model similar to the grouped amino acid model, k-spaced amino acid group pair (CKSAAGP), was used to compute the frequency of amino acid group pairs separated by an arbitrary number (k) of amino acid residues.

This paper also used the grouped dipeptide composition model (GDPC), which can be regarded as a combination of GAAC and DPC.

In addition, this paper used the grouped tripeptide composition model (GTPC), which can be regarded as a combination of GAAC and TPC.

Feature Selection

Feature selection is the procedure of picking out a subset from the relevant features applied in machine learning model building (Zou et al., 2016; Qiao et al., 2018; Cheng, 2019; Yang et al., 2019; Zhang M. et al., 2019; Li F. et al., 2020). The dimension of features will be decreased after feature selection, thus this procedure is named dimension reduction as well. MRMD2.0 was mainly used in this paper to reduce the feature dimensions. Each feature was given a numerical value by MRMD2.0 (the larger the number, the feature’s recognition ability will be more obvious). MRMD2.0 sorted the features in order on the basis of the ranking value. Next, the first feature with the highest value was examined for its performance. The second feature was added to examine the capability of the new feature subset. This procedure continued till examining total features. Eventually, some parameters in disparate dimensions were acquired, including F-score, accuracy, etc.

Classifier

Support Vector Machine

A support vector machine (SVM) was used for prediction in this study. SVM has been widely applied in the proteome prediction (Jiang et al., 2013; Wei et al., 2016, 2018; Ding et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2017; Qu et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017, 2018; Guo and Xu, 2018; Xu et al., 2018a, b; Zhang et al., 2018a; Chao et al., 2019; Chen Z. et al., 2019; Fang et al., 2019; Hong Z. et al., 2019; Liu and Li, 2019; Yu and Gao, 2019; Zeng et al., 2019b; Dao et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020), transcriptome (Chen X. et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2017) and genome (Zeng et al., 2017; Song et al., 2018; Deng et al., 2019b; Hong Z. et al., 2019). Therefore, support vector machine is a pretty useful classifier. libSVM was adopted in this paper to optimize the prediction results of SVM utilizing grid method to correct parameters g and c.

Random Forest

Random forest (rf) has been extensively applied as a classifier in chemoinformatics (Zeng et al., 2019b,2020a,b; Song et al., 2020) and bioinformatics (Zhang J. et al., 2016; Guo and Xu, 2018; Deng et al., 2019a; Liu et al., 2019a; Lv H. et al., 2019; Lv Z. et al., 2019; Lv et al., 2020; Ru et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Rf was applied in this paper.

LibD3C

At the same time, this paper used the LibD3C classifier (Lin et al., 2014) for prediction to examine the performance of the model. The classifier adopts the strategy of selective integration, based on the hybrid integrated pruning model on the basis of k-means clustering and functional selection cycle framework and sequential search, by training multiple classifiers and selecting a group of accurate and diversified classifiers to solve the problem.

Prediction Result Estimate

It is extremely critical to quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of the method because the benchmark data set is non-balanced data. This paper used Mathew correlation coefficient (Mcc), specificity (Sp),sensitivity (Sn), total accuracy (Acc) and the F-score value (F-score) phase to evaluate the performance of the model (Li et al., 2015, 2017; Wei et al., 2017; Chu et al., 2019; Ding et al., 2019; Gong et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2019; Shan et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2019; Yu and Gao, 2019; Zeng et al., 2019a,2020b; Zhang et al., 2019b; Liu X. et al., 2020; Wang H. et al., 2020).

where TP stands for the quantity of anticancer peptides correctly predicted, FP stands for the quantity of non-anticancer peptides predicted as anticancer peptides, TN stands for the correctly predicted quantity of non-anticancer peptides, and FN stands for the quantity of anticancer peptides predicted as non-anticancer peptides. P represents the accuracy, indicating the proportion of the total number of predicted positive cases; R is the recall rate, indicating the number of correct cases identified and accounting for the total number of cases in this category.

Results and Discussion

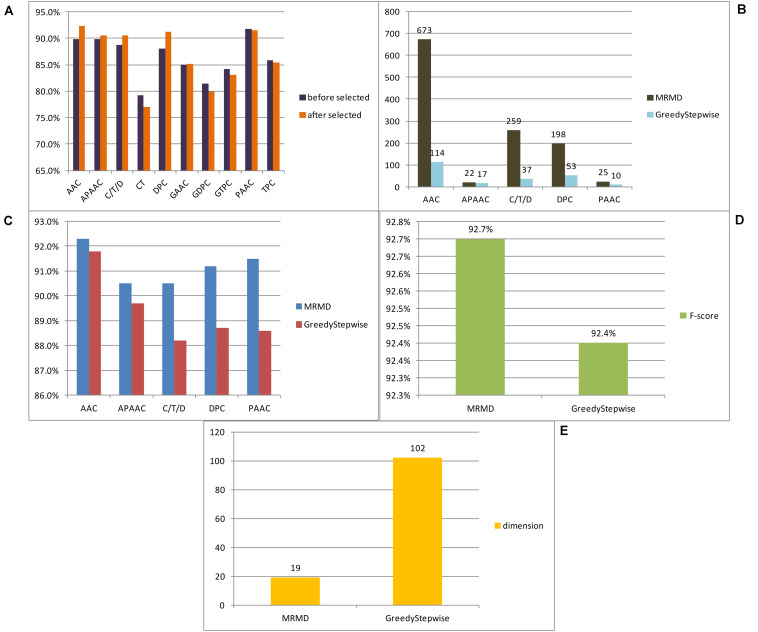

In this paper, a total of 12 feature extraction methods were used. Because the number of dimensions of the amino acid composition model was only 20, it is of little significance to reduce the dimensionality of the amino acid composition model alone, and the k-spaced amino acid pair composition model is an extension of this method. The principles of the two models were similar, and so the two models were merged and expressed uniformly by AAC. Similarly, the grouped amino acid composition model and the k-spaced amino acid group pair model were merged and expressed uniformly by GAAC. To compare the advantages and disadvantages of different feature extraction methods for anticancer peptide sequences, each model obtained by each method was examined by 10-fold cross-validation utilizing the random forest classifier, and then 10-fold cross-validation was carried out for each method after dimensional reduction through MRMD2.0. Figure 2A lists the F-score of each feature extraction method before and after feature selection. In this paper, according to the verification results, it is believed that the effects of the CT, GAAC, GDC, GTC, and TC methods were not ideal, so the above model was not considered in the follow-up study. To compare the advantages and disadvantages of different feature selection methods, the greedy algorithm and MRMD2.0 were used to select each feature model. Figure 2B lists the dimensions of each feature model after two kinds of software selection, and Figure 2C lists the F-score of each feature model after two kinds of software selection. For the feature selection method of anticancer peptide, after synthesizing the situation of all types of model selection, MRMD2.0 was better than the greedy algorithm in terms of the capability index of the selected model; As for the dimensions of the selected model, the greedy algorithm was more efficient than MRMD2.0. However, the greedy algorithm cannot further reduce the dimensions of the selected feature model, but MRMD2.0 can still further reduce it.

FIGURE 2.

The results of different experiments. (A) According to the results, this paper thought that the CT, GAAC, GDPC, GTPC, and TPC are not ideal. (B) According to the results, this paper thought that the greedy algorithm was more efficient than MRMD2.0. (C) According to the results, this paper thought that the greedy algorithm is worse than MRMD2.0 in the performance index of the selected model. (D) After several dimension reductions, the results showed that the MRMD2.0 was better than the greedy algorithm index of the selected model. (E) After several dimension reductions, the results showed that the dimension of model of the greedy algorithm is about five times that of the MRMD2.0. The results showed that as for the dimensions of the selected model, the greedy algorithm was more efficient than MRMD2.0. However, the greedy algorithm cannot further reduce the dimensions of the selected feature model, but MRMD2.0 can still further reduce it.

The feature subset of each method was merged and reduced to get a 102D feature model after selected by the greedy algorithm. The F-score value was 0.924 after random forest 10-fold cross-validation. At this time, it was impossible to use the greedy algorithm to further reduce the dimensions of the model.

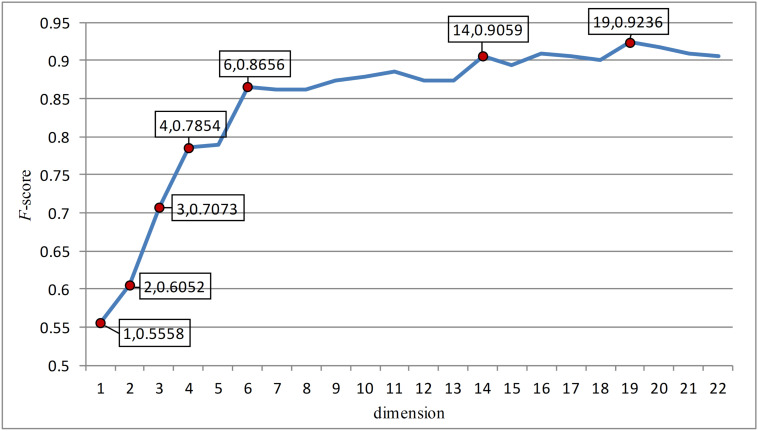

After merging the selected feature model by MRMD2.0, the model dimension number was 1177. This paper continued to use MRMD2.0 to reduce the dimension of the model to get a 767-dimensional feature model which was still too high. After continuing to reduce the dimensionality of the model again to obtain 633 dimensional features, the result was still not ideal. In this paper, the dimensionality reduction was carried out 6 times. For each dimensionality reduction, a line chart of F-score was drawn changing with the dimension according to the obtained indicators. The feature points were separated with large changes in the line to form a new model for verification, and the results were not ideal. After 8 times of dimensionality reduction, a 19-dimensional feature model was obtained. At this time, it was no longer possible to use MRMD2.0 for dimensionality reduction. Figures 2D,E list the feature model F-score and dimensions separated by the two methods, respectively. By comparison, MRMD2.0 was found to be better than the greedy algorithm.

The 19-dimensional model was tested by random forest, support vector machine (parameters c and g are 8192.0 and 0.00048828125, respectively) and LibD3C, respectively. Table 1 listed the prediction results of three types of classifiers. The results indicated that the performance of the 19-dimensional model separated in this paper is stable. Table 1 also lists the prediction results of others based on the same data set. Compared with Hajisharifi et al.’s and Xu et al.’s models, the model in this paper performs better in all prediction indicators. Although it is slightly inferior to Chen et al. in the prediction results, the number of dimensions of their model was 126, while the number of dimensions of this paper is 19, which is obviously lower than that in the previous study. By evaluating the performance of the model and comparing it with the previous work, this paper believed that the 19-dimensional model proposed in this paper can be used to predict the anticancer peptide conveniently, quickly and accurately.

TABLE 1.

Comparing the performance of different methods.

| Methods | Sn | Sp | Acc | MCC | F-score | Dimension |

| iACP | 88.40% | 99.02% | 94.77% | 89.30% | 126 | |

| Hajisharifi et al. | 85.18% | 92.68% | 89.70% | 78.40% | ||

| SAP | 86.23% | 95.63% | 91.86% | 83.01% | 89.47% | 400 |

| Our method(RF) | 86.20% | 97.10% | 92.73% | 84.90% | 92.70% | 19 |

| Our method(LibD3C) | 85.50% | 96.60% | 92.15% | 83.70% | 92.10% | 19 |

| Our method(SVM) | 87.70% | 96.10% | 92.73% | 84.80% | 92.70% | 19 |

In this paper, the feature points with large slopes in the last reduced-dimension line chart (Figure 3) were separated to form a 7-dimensional model, which was verified by support vector machine with an accuracy of 90.41%. This possibly imply that these seven-dimensional features are important features to distinguish anticancer peptides. These 7-dimensional features are GL.gap4, hydrophobicity_PRAM900101.Tr2332, polarizability.2.residue0, Pc1.C, Xc1.K, Pc2.Hydrophobicity.8, and secondarystruct.1.residue0. These features may suggest that for anticancer peptides, the composition and content of glycine, leucine, cysteine and lysine as well as their secondary structure, polarization and hydrophobicity are important indicators different from other non-anticancer peptides.

FIGURE 3.

The figure was the change of F-score with dimension according to the last dimension reduction. The red dots in the figure were the feature points with great changes in this paper. And these points were separated to form a new feature model and verified. After verification, these seven red dots are the most important seven features.

Conclusion

In this paper, a low-dimensional feature model with better performance was obtained through feature extraction and continuous feature selection over many iterations. The features were further isolated, and a few features that might distinguish anticancer peptides were identified. It is hoped that the results of this paper can be used in the artificial design and prediction of anticancer peptides.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

QWL and SW conceived and designed the research. QWL and WZ performed the machine learning experiments. QWL, DW, and QYL analyzed the data. QWL and WZ wrote the manuscript. QYL and SW coordinated the study and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript used iFeature online tool to extract features, used random forest classifier through Weka platform, and used MRMD2.0 to reduce dimensions. Yuwei Jiang and Dongyuan Yu contributed to the language editing of this article. Yuwei Jiang and Dongyuan Yu are from Tianjin Normal University and Northeast Agricultural University, respectively.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2020.00892/full#supplementary-material

References

- Chao L., Wei L., Zou Q. (2019). SecProMTB: a SVM-based classifier for secretory proteins of mycobacterium tuberculosis with imbalanced data set. Proteomics 19:e1900007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Zhang Q., Ma Q., Yu B. (2019). LightGBM-PPI: predicting protein-protein interactions through LightGBM with multi-information fusion. Chemometr. Intellig. Lab. Syst. 191 54–64. 10.1016/j.chemolab.2019.06.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Zhao P., Li F., Marquez-Lago T., Leier A., Revote J., et al. (2019). iLearn: an integrated platform and meta-learner for feature engineering, machine learning analysis and modeling of DNA, RNA and protein sequence data. Briefings Bioinform. 21 1047–1057. 10.1093/bib/bbz041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Ding H., Feng P., Lin H., Chou K.-C. (2016). iACP: a sequence-based tool for identifying anticancer peptides. Oncotarget 7:7815. 10.18632/oncotarget.7815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Pérez-Jiménez M. J., Valencia-Cabrera L., Wang B., Zeng X. (2016). Computing with viruses. Theoret. Computer Sci. 623 146–159. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z., Zhao P., Li F., Leier A., Marquez-Lago T. T., Wang Y., et al. (2018). iFeature: a Python package and web server for features extraction and selection from protein and peptide sequences. Bioinform. J. 34 2499–2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L. (2019). Computational and biological methods for gene therapy. Curr. Gene Ther. 19 210–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Jiang Y., Ju H., Sun J., Peng J., Zhou M., et al. (2018). InfAcrOnt: calculating cross-ontology term similarities using information flow by a random walk. BMC Genomics 19(Suppl. 1):919. 10.1186/s12864-017-4338-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Yang H., Zhao H., Pei X., Shi H., Sun J., et al. (2019a). MetSigDis: a manually curated resource for the metabolic signatures of diseases. Brief Bioinform. 20 203–209. 10.1093/bib/bbx103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Zhao H., Wang P., Zhou W., Luo M., Li T., et al. (2019b). Computational methods for identifying similar diseases. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 18 590–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou K.-C. (2001). Prediction of protein cellular attributes using pseudo-amino acid composition. Proteins 43 246–255. 10.1002/prot.1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu Y., Kaushik A. C., Wang X., Wang W., Zhang Y., Shan X., et al. (2019). DTI-CDF: a cascade deep forest model towards the prediction of drug-target interactions based on hybrid features. Brief Bioinform. 2019:bbz152. 10.1093/bib/bbz152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao F. Y., Lv H., Zulfiqar H., Yang H., Su W., Gao H., et al. (2020). A computational platform to identify origins of replication sites in eukaryotes. Brief Bioinform. 2020:bbaa017. 10.1093/bib/bbaa017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Li W., Zhang J. (2019a). “LDAH2V: Exploring meta-paths across multiple networks for lncRNA-disease association prediction,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, Piscataway, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L., Wang J., Zhang J. (2019b). Predicting gene ontology function of human micrornas by integrating multiple networks. Front. Genet. 10:3 10.3389/fmicb.2018.0003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Tang J., Guo F. (2017). Identification of drug-target interactions via multiple information integration. Inform. Sci. 418–419 546–560. 10.1016/j.ins.2017.08.045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y., Tang J., Guo F. (2019). Identification of drug-side effect association via multiple information integration with centered kernel alignment. Neurocomputing 325 211–224. 10.1016/j.neucom.2018.10.028 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubchak I., Muchnik I., Holbrook S. R., Kim S. H. (1995). Prediction of protein folding class using global description of amino acid sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92 8700–8704. 10.1073/pnas.92.19.8700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang T., Zhang Z., Sun R., Zhu L., He J., Huang B., et al. (2019). RNAm5CPred: prediction of RNA 5-methylcytosine sites based on three different kinds of nucleotide composition. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 18 739–747. 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. M. (2019). Gene therapy on the road. Curr. Gene Ther. 19:6. 10.2174/1566523219999190426144513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y., Niu Y., Zhang W., Li X. (2019). A network embedding-based multiple information integration method for the MiRNA-disease association prediction. BMC Bioinform. 20:468. 10.1186/s12859-019-3063-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo M., Xu Y. (2018). Single-cell transcriptome analysis using SINCERA pipeline Transcriptome. Data Analy. 1751 209–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajisharifi Z., Piryaiee M., Mohammad Beigi M., Behbahani M., Mohabatkar H. (2014). Predicting anticancer peptides with Chou’s pseudo amino acid composition and investigating their mutagenicity via Ames test. J. Theor. Biol. 341 34–40. 10.1016/j.jtbi.2013.08.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J., Luo Y., Zhang Y., Ying J., Xue W., Xie T., et al. (2019). Protein functional annotation of simultaneously improved stability, accuracy and false discovery rate achieved by a sequence-based deep learning. Brief Bioinform. 21 1437–1447. 10.1093/bib/bbz081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z., Zeng X., Wei L., Liu X. J. B. (2019). Identifying enhancer-promoter interactions with neural network based on pre-trained DNA vectors and attention mechanism. Bioinformatics 36 1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Q., Chen Y., Liu L., Tao D., Li X. (2020). On combining biclustering mining and adaboost for breast tumor classification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 32 728–738. 10.1109/TKDE.2019.2891622 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C. Z., Zuo Y., Zou Q. (2018). O-GlcNAcPRED-II: an integrated classification algorithm for identifying O-GlcNAcylation sites based on fuzzy undersampling and a K-means PCA oversampling technique. Bioinformatics 34 2029–2036. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q. H., Wang G. H., Jin S. L., Li Y., Wang Y. D. (2013). Predicting human microRNA-disease associations based on support vector machine. Intern. J. Data Min. Bioinform. 8 282–293. 10.1504/ijdmb.2013.056078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Tang J., Yang Q., Li S., Cui X., Li Y., et al. (2017). NOREVA: normalization and evaluation of MS-based metabolomics data. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 W162–W170. 10.1093/nar/gkx449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F., Zhou Y., Zhang X., Tang J., Yang Q., Zhang Y., et al. (2020). SSizer: determining the sample sufficiency for comparative biological study. J. Mol. Biol. 432:3411. 10.1016/j.jmb.2020.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. H., Li X. X., Hong J. J., Wang Y. X., Fu J. B., Yang H., et al. (2020). Clinical trials, progression-speed differentiating features and swiftness rule of the innovative targets of first-in-class drugs. Brief Bioinform. 21 649–662. 10.1093/bib/bby130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Yu J., Lian B., Sun H., Li J., Zhang M., et al. (2015). Identifying prognostic features by bottom-up approach and correlating to drug repositioning. PLoS One 10:e0118672. 10.1371/journal.pone.0118672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C., Changlu Q., He Z., Tongze F., Xue Z. (2019). gutMDisorder: a comprehensive database for dysbiosis of the gut microbiota in disorders and interventions. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 D554–D560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y.-D., Jiang Z.-R. (2019). MoABank: an integrated database for drug mode of action knowledge. Curr. Bioinform. 14 446–449. 10.2174/1574893614666190416151344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Z. J., Li D. P., Wang X. R., Li L. S., Zou Q. (2018). Cancer diagnosis through isomir expression with machine learning method. Curr. Bioinform. 13 57–63. 10.2174/1574893611666160609081155 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C., Chen W., Qiu C., Wu Y., Krishnan S., Zou Q. (2014). LibD3C: ensemble classifiers with a clustering and dynamic selection strategy. Neurocomputing 123 424–435. 10.1016/j.neucom.2013.08.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Liang Z. Y., Tang H., Chen W. (2017). Identifying sigma70 promoters with novel pseudo nucleotide composition. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 16 1316–1321. 10.1109/TCBB.2017.2666141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Li X., Guo H., Ji F., Ye L., Ma X., et al. (2019). Identification of bone metastasis-associated genes of gastric cancer by genome-wide transcriptional profiling. Curr. Bioinform. 14 62–69. 10.2174/1574893612666171121154017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Chen S., Yan K., Weng F. (2019a). iRO-PsekGCC: identify DNA replication origins based on pseudo k-tuple GC composition. Front. Genet. 10:842 10.3389/fmicb.2018.0842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Gao X., Zhang H. (2019b). BioSeq-Analysis2.0: an updated platform for analyzing DNA, RNA, and protein sequences at sequence level and residue level based on machine learning approaches. Nucleic Acids Res. 47:e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Li K. (2019). iPromoter-2L2.0: identifying promoters and their types by combining smoothing cutting window algorithm and sequence-based features. Mol. Ther.Nucleic Acids 18 80–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Luo L. B., Cheng Z. Z., Sun J. J., Guan J. H., Zheng J., et al. (2018). Group-sparse modeling drug-kinase networks for predicting combinatorial drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Curr. Bioinform. 13 437–443. 10.2174/1574893613666180118104250 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S., Liu C., Deng L. (2018). Machine learning approaches for protein-protein interaction hot spot prediction: progress and comparative assessment. Molecules 23:2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang W., Zou B., Wang J., Deng Y., Deng L. (2020). DrugCombDB: a comprehensive database of drug combinations toward the discovery of combinatorial therapy. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 D871–D881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Hong Z., Liu J., Lin Y., Rodríguez-Patón A., Zou Q., et al. (2020). Computational methods for identifying the critical nodes in biological networks. Briefings Bioinform. 21 486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Meng X., Xu Q., Flower D. R., Li T. (2006). Quantitative prediction of mouse class I MHC peptide binding affinity using support vector machine regression (SVR) models. BMC Bioinform. 7:182. 10.1186/1471-2105-7-182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Dao F.-Y., Zhang D., Guan Z.-X., Yang H., Su W., et al. (2020). iDNA-MS: an integrated computational tool for detecting DNA modification sites in multiple genomes. iScience 23:100991. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.100991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Zhang Z. M., Li S. H., Tan J. X., Chen W., Lin H. (2019). Evaluation of different computational methods on 5-methylcytosine sites identification. Briefings Bioinform. 21 982–995. 10.1093/bib/bbz048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Z., Jin S., Ding H., Zou Q. (2019). A random forest sub-Golgi protein classifier optimized via dipeptide and amino acid composition features. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7:215. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munir A., Malik S. I., Malik K. A. (2019). Proteome mining for the identification of putative drug targets for human pathogen clostridium tetani. Curr. Bioinform. 14 532–540. 10.2174/1574893613666181114095736 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan A., Isgor S. B., Sengul G., Isgor Y. G. (2019). Benchmarking classification models for cell viability on novel cancer image datasets. Curr. Bioinform. 14 108–114. 10.2174/1574893614666181120093740 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y., Xiong Y., Gao H., Zhu X., Chen P. (2018). Protein-protein interface hot spots prediction based on a hybrid feature selection strategy. BMC Bioinform. 19:14. 10.1186/s12859-018-2009-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu K., Han K., Wu S., Wang G., Wei L. (2017). Identification of DNA-binding proteins using mixed feature representation methods. Molecules 22:1602. 10.3390/molecules22101602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru X., Wang L., Li L., Ding H., Ye X., Zou Q. (2020). Exploration of the correlation between GPCRs and drugs based on a learning to rank algorithm. Comput. Biol. Med. 119:103660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ru X. Q., Li L. H., Zou Q. (2019). Incorporating Distance-based top-n-gram and random forest to identify electron transport proteins. J. Proteome Res. 18 2931–2939. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan X., Wang X., Li C. D., Chu Y., Zhang Y., Xiong Y., et al. (2019). Prediction of CYP450 enzyme-substrate selectivity based on the network-based label space division method. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 59 4577–4586. 10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Zhang J., Luo X., Zhu W., Yu K., Chen K., et al. (2007). Predicting protein-protein interactions based only on sequences information. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 4337–4341. 10.1073/pnas.0607879104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B., Li K., Orellana-Martín D., Valencia-Cabrera L., Pérez-Jiménez M. J. (2020). Cell-like P systems with evolutional symport/antiport rules and membrane creation. Inform. Comput. 2020:104542. [Google Scholar]

- Song T., Rodríguez-Patón A., Zheng P., Zeng X. (2018). Spiking neural P systems with colored spikes. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 10 1106–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava N., Mishra B. N., Srivastava P. (2019). In-silico identification of drug lead molecule against pesticide exposed-neurodevelopmental disorders through network-based computational model approach. Curr. Bioinform. 14 460–467. 10.2174/1574893613666181112130346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Zhang W., Chen Y., Ma Q., Wei J., Liu Q. (2016). Identifying anti-cancer drug response related genes using an integrative analysis of transcriptomic and genomic variations with cell line-based drug perturbations. Oncotarget 7:9404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Deng Z.-H., Nie J.-Y., Tang J. (2019). Rotate: knowledge graph embedding by relational rotation in complex space. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv:1902.10197v1 [Google Scholar]

- Tan J. X., Li S. H., Zhang Z. M., Chen C. X., Chen W., Tang H., et al. (2019). Identification of hormone binding proteins based on machine learning methods. Math. Biosci. Eng. 16 2466–2480. 10.3934/mbe.2019123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Fu J., Wang Y., Li B., Li Y., Yang Q., et al. (2020). ANPELA: analysis and performance assessment of the label-free quantification workflow for metaproteomic studies. Brief Bioinform. 21 621–636. 10.1093/bib/bby127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J., Fu J., Wang Y., Luo Y., Yang Q., Li B., et al. (2019). Simultaneous improvement in the precision, accuracy, and robustness of label-free proteome quantification by optimizing data manipulation chains. Mol. Cell Proteom. 18 1683–1699. 10.1074/mcp.RA118.001169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y., Liu D., Wang Z., Wen T., Deng L. (2017). A boosting approach for prediction of protein-RNA binding residues. BMC Bioinform. 18:465 10.1186/s12859-018-2009-465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagi A., Kapoor P., Kumar R., Chaudhary K., Gautam A., Raghava G. P. (2013). In silico models for designing and discovering novel anticancer peptides. Sci. Rep. 3:2984. 10.1038/srep02984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Ding Y., Tang J., Guo F. (2020). Identification of membrane protein types via multivariate information fusion with Hilbert-Schmidt Independence criterion. Neurocomputing 383 257–269. 10.1016/j.neucom.2019.11.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang H., Wang X., Chang H. (2020). Predicting drug-target interactions via FM-DNN learning. Curr. Bioinform. 15 68–76. 10.2174/1574893614666190227160538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Zhang S., Li F., Zhou Y., Zhang Y., Wang Z., et al. (2020). Therapeutic target database 2020: enriched resource for facilitating research and early development of targeted therapeutics. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 D1031–D1041. 10.1093/nar/gkz981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Yu B., Ma A., Chen C., Liu B., Ma Q. (2018). Protein-protein interaction sites prediction by ensemble random forests with synthetic minority oversampling technique. Bioinformatics 35 2395–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Ding Y., Guo F., Wei L., Tang J. (2017). Improved detection of DNA-binding proteins via compression technology on PSSM information. PLoS One 12:185587. 10.1371/journal.pone.0185587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu K., Ma Q., Tan Y., Du W., Lv Y., et al. (2019). Pancreatic cancer biomarker detection by two support vector strategies for recursive feature elimination. Biomark. Med. 13 105–121. 10.2217/bmm-2018-0273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Wan S., Guo J., Wong K. K. (2017). A novel hierarchical selective ensemble classifier with bioinformatics application. Artif. Intellig. Med. 83 82–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Zhou C., Chen H., Song J., Su R. (2018). ACPred-FL: a sequence-based predictor based on effective feature representation to improve the prediction of anti-cancer peptides. Bioinformatics 34 4007–4016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Zhou C., Su R., Zou Q. (2019). PEPred-Suite: improved and robust prediction of therapeutic peptides using adaptive feature representation learning. Bioinformatics 35 4272–4280. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei L., Zou Q., Liao M., Lu H., Zhao Y. (2016). A novel machine learning method for cytokine-receptor interaction prediction. Combinat. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 19 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox R. (1961). Adaptive control processes—A guided tour, by richard bellman, princeton university press, princeton, New Jersey, 1961, 255 pp., $6.50. Naval Res. Logist. Q. 8:314 10.1002/nav.3800080314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Y., Wang Q., Yang J., Zhu X., Wei D. Q. (2018). PredT4SE-Stack: prediction of bacterial Type IV secreted effectors from protein sequences using a stacked ensemble method. Front. Microbiol. 9:2571. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Liang G., Liao C., Chen G.-D., Chang C.-C. (2018a). An efficient classifier for alzheimer’s disease genes identification. Molecules 23:3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Liang G., Wang L., Liao C. (2018b). A novel hybrid sequence-based model for identifying anticancer peptides. Genes 9:158. 10.3390/genes9030158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Zhao W., Olson S. D., Prabhakara K. S., Zhou X. (2018). Alternative splicing links histone modifications to stem cell fate decision. Genome Biol. 19 1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Liang G., Liao C., Chen G.-D., Chang C.-C. (2019). k-Skip-n-Gram-RF: a random forest based method for Alzheimer’s disease protein identification. Front. Genet. 10:33. 10.3389/fgene.2019.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wang Y., Luo J., Zhao W., Zhou X. (2017). Deep learning of the splicing (epi)genetic code reveals a novel candidate mechanism linking histone modifications to ESC fate decision. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 12100–12112. 10.1093/nar/gkx870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan K., Fang X., Xu Y., Liu B. (2019). Protein fold recognition based on multi-view modeling. Bioinformatics 35 2982–2990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Li B., Tang J., Cui X., Wang Y., Li X., et al. (2019). Consistent gene signature of schizophrenia identified by a novel feature selection strategy from comprehensive sets of transcriptomic data. Brief Bioinform. 21 1058–1068. 10.1093/bib/bbz049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Li F., Xia W., Zhou Y., et al. (2020). NOREVA: enhanced normalization and evaluation of time-course and multi-class metabolomic data. Nucleic Acids Res. 48 W436–W448. 10.1093/nar/gkaa258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Sun W., Li F., Hong J., Li X., Zhou Y., et al. (2020). VARIDT 1.0: variability of drug transporter database. Nucleic Acids Res 48 D1042–D1050. 10.1093/nar/gkz779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Gao L. (2019). Human pathway-based disease network. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 16 1240–1249. 10.1109/TCBB.2017.2774802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Xu F., Gao L. (2020). Predict new therapeutic drugs for hepatocellular carcinoma based on gene mutation and expression. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:8. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W., Wang F., Ma Y., Liang X. C., Chen P. (2019). Dysfunctional mechanism of liver cancer mediated by transcription factor and non-coding RNA. Curr. Bioinform. 14 100–107. 10.2174/1574893614666181119121916 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Wang W., Deng G., Bing J., Zou Q. (2019a). Prediction of potential disease-associated MicroRNAs by using neural networks. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 16 566–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Zhu S., Liu X., Zhou Y., Nussinov R., Cheng F. (2019b). deepDR: a network-based deep learning approach to in silico drug repositioning. Bioinformatics 35 5191–5198. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Liao Y., Liu Y., Zou Q. (2017). Prediction and validation of disease genes using hetesim scores. IEEE/ACM Trans. Comput. Biol. Bioinform. 14 687–695. 10.1109/tcbb.2016.2520947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Zhu S., Hou Y., Zhang P., Li L., Li J., et al. (2020a). Network-based prediction of drug-target interactions using an arbitrary-order proximity embedded deep forest. Bioinformatics 36 2805–2812. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X., Zhu S., Lu W., Liu Z., Huang J., Zhou Y., et al. (2020b). Target identification among known drugs by deep learning from heterogeneous networks. Chem. Sci. 11 1775–1797. 10.1039/C9SC04336E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Ju Y., Lu H., Xuan P., Zou Q. (2016). Accurate identification of cancerlectins through hybrid machine learning technology. Int. J. Genom. 2016:7604641. 10.1155/2016/7604641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M., Li F., Marquez-Lago T. T., Leier A., Fan C., Kwoh C. K., et al. (2019). MULTiPly: a novel multi-layer predictor for discovering general and specific types of promoters. Bioinformatics 35 2957–2965. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Jing K., Huang F., Chen Y., Li B., Li J., et al. (2019a). SFLLN: a sparse feature learning ensemble method with linear neighborhood regularization for predicting drug-drug interactions. Inform. Sci. 497 189–201. 10.1016/j.ins.2019.05.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Li Z., Guo W., Yang W., Huang F. (2019b). “A fast linear neighborhood similarity-based network link inference method to predict microRNA-disease associations,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform, Piscataway, NJ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Kou C., Wang S., Zhang Y. (2019). Genome-wide differential-based analysis of the relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression in cancer. Curr. Bioinform. 14 783–792. 10.2174/1574893614666190424160046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Chen Y., Li D., Yue X. (2018a). Manifold regularized matrix factorization for drug-drug interaction prediction. J. Biomed. Inform. 88 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W., Yue X., Tang G., Wu W., Huang F., Zhang X. (2018b). SFPEL-LPI: sequence-based feature projection ensemble learning for predicting LncRNA-protein interactions. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14:e1006616. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1006616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. M., Tan J. X., Wang F., Dao F. Y., Zhang Z. Y., Lin H. (2020). Early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma using machine learning method. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:254. 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. Y., Qin Z., Zhu Y. H., He Z. Y., Xu T. (2019). Current RNA-based therapeutics in clinical trials. Curr. Gene Ther. 19 172–196. 10.2174/1566523219666190719100526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Q., Chen L., Huang T., Zhang Z., Xu Y. (2017). Machine learning and graph analytics in computational biomedicine. Artif. Intell. Med. 83:1. 10.1016/j.artmed.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Q., Wan S., Ju Y., Tang J., Zeng X. (2016). Pretata: predicting TATA binding proteins with novel features and dimensionality reduction strategy. BMC Syst. Biol. 10:114 10.1186/s12859-018-2009-114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.