Abstract

In the fall of 2014, Health Quality Ontario1 released A Primary Care Performance Measurement Framework for Ontario. Recognizing the large number of recommended measures and the limited availability of data related to those measures, the Steering Committee for the Primary Care Performance Measurement (PCPM) initiative established a prioritization process to select two subsets of high-value performance measures – one at the system level and one at the practice level. This article describes the prioritization process and its results and outlines the initiatives that have been undertaken to date to implement the PCPM framework and to advance primary care performance measurement and reporting in Ontario. Establishing a framework for primary care measurement and prioritizing system- and practice-level measures are essential steps toward system improvement. Our experience suggests that the process of implementing a performance measurement system is inevitably non-linear and incremental.

Abstract

À l'automne 2014, Qualité des services de santé Ontario1 publiait le Cadre de mesure du rendement des soins primaires en Ontario. Conscient du nombre important de mesures recommandées et de la disponibilité limitée des données associées à ces mesures, le comité directeur pour la mesure du rendement des soins primaires (MRSP) a mis au point un processus de priorisation afin de sélectionner deux sous-ensembles de mesures de la performance à forte valeur ajoutée – le premier au niveau du système, l'autre au niveau des cabinets. Cet article décrit le processus de priorisation et ses résultats, puis souligne les initiatives qui ont été entreprises à ce jour pour mettre en œuvre le cadre de MRSP et pour favoriser, en Ontario, la mesure du rendement et la publication de rapports en ce sens. La mise au point d'un cadre de mesure du rendement des soins primaires et la priorisation de telles mesures au niveau du système et des cabinets sont des étapes essentielles pour l'amélioration du système. Notre expérience suggère que le processus de mise en œuvre d'un système de mesure de la performance est inévitablement non linéaire et incrémentiel.

Introduction

In the fall of 2014, Health Quality Ontario2 released A Primary Care Performance Measurement Framework for Ontario (Health Quality Ontario 2014).The performance measurement framework had been developed by a steering committee representing 20 stakeholder organizations encompassing patients, family caregivers, healthcare providers, data holders, researchers, managers, policy makers and funders. The Steering Committee, supported by measures selection and technical working groups, identified 179 candidate system-level measures and 112 candidate practice-level measures across nine domains (access, patient-centredness, safety, effectiveness, efficiency, integration, focus on population health and appropriate resources, with equity as a cross-cutting domain) that were deemed valuable to have available on a regular basis to inform policy development, service planning, management and quality improvement.3 A total of 92 candidate measures are common to both subsets. Details of the Primary Care Performance Measurement (PCPM) framework are described elsewhere (Haj-Ali and Hutchison 2017).

Recognizing the large number of recommended measures and the limited availability of data related to those measures, particularly at the practice level, the Steering Committee identified the need to undertake a prioritization process to select two subsets of high-value performance measures – one at the system level and one at the practice level – for which data are already available or could be made available in the short to medium term.

This report describes the process and its results and outlines the initiatives that have been undertaken to date to implement the PCPM framework and to advance primary care performance measurement and reporting in Ontario.

Methods

The system- and practice-level prioritization processes were conducted separately but in parallel and were guided by the PCPM Steering Committee. The Health Quality Ontario staff supported both processes, which engaged expert working groups that included primary care providers, policy makers, managers, researchers and patient representatives. Working group members were chosen to reflect different primary care organizational models and knowledge of health system issues and priorities, the PCPM framework, measures and relevant data sources and existing data and measurement capacity. The system-level working group consisted of 12 representatives of primary care stakeholder organizations (e.g., Ontario College of Family Physicians, Nurse Practitioners' Association of Ontario), healthcare decision-makers (Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Local Health Integration Networks), organizations with data collection and analysis expertise (e.g., Canadian Institute for Health Information [CIHI], Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences) and patients. The practice-level working group comprised 10 representatives of primary care provider organizations. The two expert panels used slightly different prioritization processes to reflect the focus on system or practice, but both applied pre-defined selection criteria and prioritized measures through consensus building. The criteria assessed importance, actionability, validity, data availability and alignment with other initiatives. The PCPM Steering Committee reviewed and approved the final subsets of system- and practice-level measures.

System-level prioritization

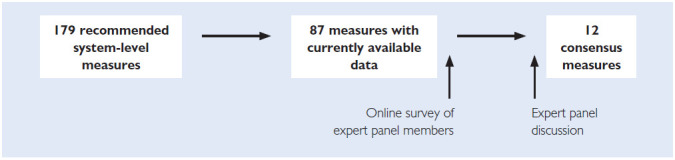

For the system-level prioritization, the panel was asked to prioritize the 87 candidate system-level PCPM measures for which data were currently available. The initial prioritization was limited to measures for which data were available to ensure that immediate measurement was possible. The process (Figure 1) included an independent online survey to rate measures against the selection criteria and in-person meetings to achieve consensus on the final set of recommended system-level measures. The panel focused on the validity, relevance and actionability of the measures to key audiences: patients, caregivers, primary care providers and decision-makers. To further aid the consensus process, the panel also considered alignment with other primary care measurement initiatives. The final set of system-level measures encompassed the eight domains of the PCPM framework. In addition, the panel recommended stratifications that should be included to measure performance across the ninth cross-cutting equity domain.

Figure 1.

System-level prioritization

Practice-level prioritization

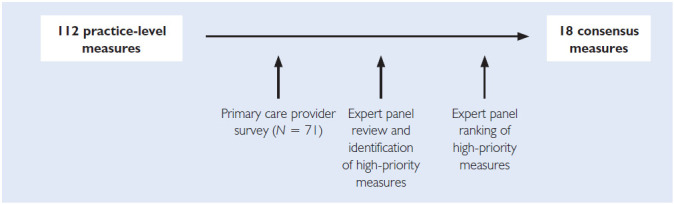

We enlisted front-line primary care providers to select (via an online survey) measures from the full list of 112 candidate measures. This approach differed from that of the system-level prioritization in that all measures were considered for prioritization, without restriction to measures for which data were available. The panel decided against restriction, given the limited availability of practice-level data (at the time, data were available for only 17 of 112 candidate practice-level measures).

The process we used for the practice-level prioritization is depicted in Figure 2. We surveyed approximately 400 providers, including MyPractice: Primary Care report (Health Quality Ontario 2020) users and attendees at a primary care forum convened jointly by Health Quality Ontario and the Ontario College of Family Physicians. A total of 71 providers completed the survey. The results informed the expert panel's discussion and identification of high-priority practice-level measures. Based on the review and discussion of the survey results, the panel ranked the measures in each domain. In an effort to balance measures across the framework, the panel recommended measures ranked high in each domain to the PCPM Steering Committee for practice-level prioritization.

Figure 2.

Practice-level prioritization

Results

The system-level prioritization working group selected 12 system measures across eight domains of the PCPM framework, all of which were measurable with available provincial data. The practice-level prioritization working group selected 18 measures, 11 of which currently do not have a consistent data source, although some may be collected by individual practices through electronic medical records (EMRs) or practice surveys. Seven of the measures were common to system- and practice-level measurement; all seven are available at the system level, and five are currently available at the practice level. In addition, the practice-level working group recommended the development of two practice-level safety measures, one related to polypharmacy among older adults and another related to up-to-date allergy status recorded in patient records. Table 1 lists the measures selected, by domain, for the system and practice levels.

Table 1.

Number and current availability of measures by domain

| Domain | System-level measures | Practice-level measures | Shared measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selected | Available | Selected | Available | Selected | Available | |

| Access | 4* | 4* | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Integration | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Efficiency | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Effectiveness | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Focus on population health | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Safety | 1 | 1 | 0** | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patient-centredness | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Appropriate resources | 1* | 1* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Equity | Cross-cutting domain | Cross-cutting domain | Cross-cutting domain | |||

| Total | 12 | 11 | 18 | 7 | 7 | 5 |

One system-level access measure was cross-referenced to the domain of appropriate resources.

Two new measures not included in the current framework (polypharmacy among older persons and up-to-date recording of allergy status) were recommended for development.

The system-level working group recommended that all selected measures should be assessed from an equity perspective. In particular, the group identified attachment rate, colorectal cancer screening and diabetes complications as measures that vary significantly by sociodemographic characteristics. The practice-level working group discussed the role of population demographic measures at the practice level and recommended that such measures be included in future specifications for EMR systems to enable equity measurement at the practice level.

The full report of the prioritization process, Primary Care Performance Measurement: Priority Measures for System and Practice Levels, including the rationale, existing or potential data source and technical specifications for each measure, is available at http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/system-performance/priority-measures-system-practice-primary-care-performance-measurement-ontario-en.pdf.

Appendix 1 describes the selected measures (available online at here.

System-level data gaps

The system-level working group identified data gaps (aspects of primary care performance for which either data sources or specific data are not currently available) in a number of measurement areas. To address the immediate need for comprehensive primary care measurement, one of the measure selection criteria was currently available measures and data. However, as new data sources become available, the selected measures will need to be reviewed at regular intervals to ensure that primary care performance measurement continues to evolve and grow. System-level primary care measurement gaps that were identified as most in need of data advocacy efforts include the following:

mental health;

provider-reported measures;

comprehensiveness of care;

health promotion including tobacco smoking, obesity, injury prevention and immunization;

maternal health; and

family and caregiver information.

Practice-level data gaps

Given the limited availability of data at the practice level, the practice-level prioritization was not restricted to measures with available data. Of the measures selected at the practice level, seven are currently available. Data advocacy and development of measures are needed for the remaining 11 prioritized measures. In addition, the practice-level working group identified possible measures interpretation issues or data gaps for a number of measurement areas. Practice-level primary care measurement gaps identified as most in need of data advocacy efforts include the following:

safety;

mental health;

EMR specifications to capture and report more practice-level measures; and

aligning measures that speak to the clinician's day-to-day pressure points with other, ongoing best-practice or improvement-advocacy campaigns (e.g., Choosing Wisely Canada).

Application of the PCPM framework

Following the release of the prioritization report, Health Quality Ontario began implementing the PCPM framework by embedding the recommended and currently available system- and practice-level measures in its yearly health system performance report, Measuring Up, in the MyPractice: Primary Care report, and in priority indicators for quality improvement plans submitted annually by Community Health Centres (CHCs) and Family Health Teams (FHTs).

In line with the PCPM Steering Committee recommendations, and informed by the identified set of system-level measures, Health Quality Ontario has publicly reported on primary care performance using an online reporting platform and released two specialized reports – Quality in Primary Care: Setting a Foundation for Monitoring and Reporting in Ontario (Health Quality Ontario 2015b) and Connecting the Dots for Patients: Family Doctors' Views on Coordinating Patient Care in Ontario's Health System (Health Quality Ontario 2016).

In 2017, the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario noted in a chapter on CHCs in its annual report that the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care had informed the Auditor General's office that “this [PCPM] framework serves as the foundational component of provincial efforts to collect data and measure performance for primary care providers, including CHCs, and that it has prioritized the measures and adopted a subset of recommended measures – 18 of the 112 practice-level measures and 12 of the 179 system-level measures. (Office of the Auditor General of Ontario 2017: 207).

Health Quality Ontario publicly reports on primary care performance in two forms: its annual health system performance report, Measuring Up, and its online reporting of primary care performance (available at https://www.hqontario.ca/System-Performance/Primary-Care-Performance). In 2018, Measuring Up reported on six of the 12 prioritized PCPM system-level measures (Health Quality Ontario 2018a). None of the prioritized measures was included in the re-oriented 2019 report, but three new measures focused on primary care were added: satisfaction with waiting times to see a primary care provider, e-mailing a primary care provider with a medical question and primary care physician work stress (Health Quality Ontario 2019a). These changes reflected an effort to reduce the number of measures reported in response to feedback and the changing health delivery and policy landscape. Health Quality Ontario currently reports nine of the 12 prioritized system-level measures online. Ontario's quarterly Health Care Experience Survey (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care 2019) collects data on four system-level priority measures. The survey provides results at the district and provincial levels and, for consenting respondents, is linkable to health administrative data. Selective results are publicly reported through reports such as Measuring Up.

In partnership with ICES (formerly the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences), Health Quality Ontario makes practice-level performance data derived from health administrative data available to individual physicians, FHTs and CHCs through its MyPractice report (Health Quality Ontario 2020). The report tracks changes over time and presents district and provincial averages for comparison. The reports are available through voluntary sign-up to any primary care physician, FHT or CHC. They include all seven of the currently available practice-level priority measures. In response to the escalation of opioid overdoses and deaths in recent years, four measures related to opioid prescribing that were not identified as priorities in the 2015 prioritization process have been added to the MyPractice reports.

Ivers et al. (2018) used a selection of PCPM framework measures derived from administrative data in a Health Quality Ontario project designed to engage patients in selecting measures for a primary care audit and feedback intervention.

Through a process that engaged key stakeholders and technical experts, Health Quality Ontario developed a primary care patient experience survey designed for administration following an office visit (Health Quality Ontario 2015c). Health Quality Ontario makes the survey available for use by primary care practices and organizations but does not administer the survey or analyze the results. The questionnaire includes four of the 18 practice-level priority measures.

The Government of Ontario (through Health Quality Ontario) requires FHTs, CHCs, Aboriginal health access centres and nurse practitioner-led clinics to submit annual quality improvement plans and to report on their quality improvement results. Of the five priority quality measures identified for 2019/2020, three are PCPM practice-level priority measures (Health Quality Ontario 2019b).

Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance

Health Quality Ontario sunsetted the PCPM Steering Committee following the completion of the prioritization process and assigned responsibility for advancing primary care performance measurement to its Primary Care Quality Advisory Committee. In June 2017, Health Quality Ontario convened a roundtable of primary care partners and experts “to discuss the future of primary care audit and feedback (practice reporting) in Ontario, and opportunities for developing a shared vision and commitment towards aligned and/or integrated practice reports and other supports” (Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance 2019: 3). Meeting participants agreed to form a time-limited alliance to collaborate on improving primary care measurement and reporting in the province to support primary care clinicians' quality improvement efforts. The Alliance defined its purpose as “improv[ing] patient care and outcomes through increased alignment of reporting efforts across partner organizations, as well as improved provider experience, uptake and use of reports for quality improvement” (Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance 2019: 5)

Alliance membership included senior representation from the following performance report-producer and performance report-consumer organizations: Association of Family Health Teams of Ontario, Alliance for Healthier Communities, Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network, Cancer Care Ontario, Electronic Medical Record Administrative Data Linked Database, Health Quality Ontario, OntarioMD, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, CIHI, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, Primary Care LHIN Leadership, Nurse Practitioners' Association of Ontario, Ontario College of Family Physicians and Ontario Medical Association Section on General and Family Practice.

The Alliance reviewed seven reports targeting primary care clinicians for which its members were responsible and identified overlapping target audiences and purpose. “Overlap in purpose included improving data quality, team-level performance, population health, cancer screening and chronic disease management, and supporting accountability reporting and operational management. There is also a high degree of overlap – but not necessarily complete alignment in technical specifications and definitions – in many of the reported indicators” (Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance 2019: 4). Three of the reports drew on EMR data, and four are derived from health administrative data.

The Alliance released its report in February 2019. The report included a key recommendation to move from seven to two reports, noting that “family physicians, nurse practitioners and interprofessional teams feel overwhelmed by the number of reports and indicators” (Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance 2019: 6). Near-term tasks identified in the report included the following:

"Develop[ing] a coordinated communication plan with regard to reporting and quality improvement …"

"Implement[ing] a collaborative approach for clinical engagement …"

"Develop[ing] a joint proposal for a cost-efficient provincial patient experience measurement approach that is meaningful to practices and patients/clients, with a mechanism for timely feedback to practices and clinicians."

Medium-term tasks include the following:

"Develop[ing] and launching an integrated reporting format and platform …"

"Develop[ing] a plan for allowing practices and clinicians to select measures from a suite of indicators that reflect their needs …"

"Gain[ing] consensus on an approach to peer comparison …"

Identified longer term tasks include the following:

"Plann[ing] and deliver[ing] integrated real-time EMR reports."

The report's final recommendation was to establish a partnered working group to implement its recommendations.

Health Quality Ontario assigned responsibility for implementing the recommendations of the Alliance to the Primary Care Quality Advisory Committee. The committee's revised terms of reference state that the committee “shall provide advice on the implementation and uptake of strategies to strengthen the quality of primary care practice … A key component of the committee is to advance the recommendations from the Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance” (Health Quality Ontario 2018b: 2). Committee membership includes Health Quality Ontario's Primary Care Clinical Lead (Chair) and senior leadership, primary care clinical leaders, measurement and data systems experts, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and public health representatives and patients and family caregivers.

Discussion

Alignment with Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicators

In 2012, CIHI released its Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicator Update Report (CIHI 2012). From the 105 indicators identified in the original 2006 report, the update identified two priority subsets “for measuring and improving PHC [primary health care] in Canada” – one intended to meet the needs of policy makers and one intended to meet the needs of primary healthcare providers – based on “broad stakeholder consultations.” Only five of CIHI's 19 priority indicators for policy makers align with the PCPM system-level priority measures, and seven of 30 priority indicators for providers align with the PCPM practice-level priority measures. Interestingly, the Chair and one other member of the PCPM Steering Committee and a member of the Technical Working Group were three of the 12 members of the Advisory Panel for the CIHI indicator update project.

Primary care performance measurement in other provinces and territories

Canadian provinces and territories have all addressed primary care performance measurement to some extent, some minimally and others substantially. For example, Nova Scotia, Northwest Territories and Yukon have reported on primary care performance at the system level. Nova Scotia conducts and publicly reports on a patient experience survey that includes primary care content (Nova Scotia Health Authority 2019a). In 2019, the Nova Scotia Health Authority released Current State Assessment of the Primary Health Care System in Nova Scotia, which reported baseline data for 28 indicators selected by key stakeholders “through a multi-voting process” (Nova Scotia Health Authority 2019b). In 2014, the Yukon Government developed a health and social services performance measurement framework and reported on 14 of the 20 selected measures, several of which were relevant to primary care (Yukon Government Health and Social Services 2014). In 2015, Northwest Territories Health and Social Services developed a performance measurement framework (Northwest Territories Health and Social Services 2015a) and released reports in 2015 and 2016 on the 30 selected measures, five of which addressed primary care performance (Northwest Territories Health and Social Services 2015b, 2016). The Northwest Territories 2017 to 2018 report adopted a new framework, retained 16 of the original measures, dropped 14 and added 35 new measures (Government of Northwest Territories 2018).

Alberta makes primary care performance data available at both the practice and system levels. Beginning in 2016, the Health Quality Council of Alberta (HQCA) developed a primary care patient experience survey that was initially administered in self-selected primary care clinics (Health Quality Council of Alberta 2019a). In 2019, the survey was conducted province-wide, and in March 2019, data from the patient experience survey (eight measures) were added to the HQCA's Focus on Primary Healthcare website (Health Quality Council of Alberta 2019b), complementing seven measures of clinical care and care delivery derived from administrative data. The clinical measures are reported at the provincial, regional and primary care network levels; patient experience measures are reported only at the provincial level.

The Saskatchewan Health Quality Council (HQC) has developed two primary healthcare patient surveys: a short five-question version and a long 11-question version. The HQC supports health regions to administer and analyze the surveys with a “Getting Started Toolkit” and a Microsoft Excel tool “that generates graphs based on the survey data entered” (Saskatchewan Health Quality Council 2017: 5).

The Health Data Coalition (HDC) in British Columbia (BC) is a physician-led not-for-profit organization funded by the General Practice Services Committee, a partnership of the Government of BC and Doctors of BC (Health Data Coalition 2019). The HDC provides primary care physicians who use one of four EMRs and enroll with the HDC with no-charge access to approximately 250 EMR-based clinical measures for their patient population. Enrolled physicians can share and compare their data with other physicians in their clinic, Division of General Practice, Health Authority and province-wide. The Government of BC, Doctors of BC and the province's health authorities have partnered to develop the Measurement System for Physician Quality Improvement “to identify continuous quality improvement opportunities for individual physicians and value for money to the system” by providing physicians, health system managers and policy makers with relevant quality measures data (Doctors of BC 2019: 2). Initial development is focused on primary care and surgical care.

Although some primary care performance measures are consistent among the various provincial/territorial initiatives and with Ontario's PCPM priority measures, the degree of alignment is at most modest.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Engagement and momentum

The implementation of a provincial system of primary care performance measurement is inevitably non-linear, incremental and protracted. It requires the engagement and re-engagement over time of a large and changing cast of players. Ontario has maintained stakeholder engagement and momentum over a period of more than seven years, first during the PCPM initiative, followed by the Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance and, currently, the Primary Care Quality Advisory Committee. Without the ongoing leadership, facilitation and staff support provided by Health Quality Ontario, the process would likely have faltered. Our sense is that continued stakeholder engagement reflects a sense of being heard and having influence and confidence that current efforts will lead to important benefits for the constituencies represented by the stakeholder organizations.

The influence of framing, context and participants

The marked variation in provincial/territorial primary care performance measurement frameworks and indicators and their limited alignment with CIHI's Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicators suggest that factors such as the identified objectives and terms of reference for a performance measurement initiative, the health policy environment in which it occurs and who participates in the process substantially influence the outcome. Processes for the development of a performance measurement framework and the selection of performance measures that on the surface seem similar can produce quite different results.

Infrastructure

Ontario continues to have limited sources of primary care performance data, mainly health administrative and patient experience data. Practice-level performance measures (including peer group comparisons) derived from EMR data are available, but only to a relatively small subset of practices, due largely to a lack of sustainable infrastructure. Patient experience data are available through the Health Care Experience Survey, but only at the district and provincial levels. The net result is that most of what is important is not available. The problem is particularly acute for practice-level performance measures. To move beyond this dilemma, Ontario needs to develop and support infrastructure that would equip clinicians and practice managers with clinical and patient experience data for their practice population that is timely, supports planning and quality improvement and allows comparison with peer practices. This requires developing a mechanism to pool and analyze EMR data from across the province and to conduct a recurring provincial survey of patient experience that would provide patient-reported measures of performance at the practice level. The need for such a survey was highlighted in the report of the Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance (2019). Development and ongoing support of the needed infrastructure would require a substantial public investment.

The situation in other provinces and territories appears similar, although BC's Health Data Alliance appears to be a sustainable model that has the potential to make EMR-based performance measures available to any primary care provider who wishes to enrol.

Coordination across performance measurement and reporting initiatives

The work of the Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance demonstrates the effective use of a collaborative approach to problem identification and response, in particular the problem of multiple, overlapping performance reporting directed toward primary care clinicians. In its report, the Alliance mapped out an approach and secured a commitment from key stakeholders to address the issue. Although the goal of a common access point for all practice-level performance feedback and a consolidated report containing “information that is actionable and proven to support change” has not been achieved, a process has been established to move toward that goal.

Breadth of primary care performance measurement

Given the limits of existing data collection and analysis infrastructure and that data are currently available for only 13% of the practice-level measures and 41% of the system-level measures that were identified through the PCPM initiative as useful to measure on a regular basis to inform planning, policy and practice, the Steering Committee decided to undertake the prioritization process described earlier. However, as noted in the Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance report, ultimately clinicians and practices need to be able to “select measures from a suite of indicators that reflect their needs …” (Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance 2019: 6).

Interprovincial/territorial alignment of performance measures

The lack of alignment between CIHI's Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicators, Ontario's priority primary care performance measures and those identified in other provincial frameworks suggests that agreement among the provinces and territories on a common set of primary care performance measures is unlikely to be achieved absent a shared federal/provincial/territorial commitment to that objective based on recognition of the value of national primary care performance reporting and interprovincial comparisons of primary care performance.

Conclusion

Establishing and implementing a framework and coordinated system for primary care measurement and reporting are challenging and inevitably protracted tasks. Although the PCPM framework and prioritized measures are Ontario specific, our methods, stakeholder engagement processes and lessons learned are potentially transferable to other provinces.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Jonathan Lam for his support of the prioritization work and review of the revised manuscript.

The Methods section and the Results section to the end of the Data Gaps subsection are an edited and expanded version of these sections from the 2015 Health Quality Ontario report, Primary Care Performance Measurement: Priority Measures for System and Practice Levels. Three co-authors of the present article participated in the preparation of that report.

As of December 2019, Ontario Health (Quality), part of Ontario Health

As of December 2019, Ontario Health (Quality), part of Ontario Health

Since then, Ontario Health (Quality) has adopted the Institute of Medicine's six domains of quality (safe, effective, patient-centred, efficient, timely, equitable) through the Quality Matters Framework (Health Quality Ontario 2015a).

Contributor Information

Brian Hutchison, Professor Emeritus, Departments of Family Medicine and Health Research Methods, Evidence and Impact and the Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON.

Wissam Haj-Ali, PhD Candidate, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON.

Gail Dobell, Director, Performance Measurement, Ontario Health (Quality), Toronto, ON.

Naira Yeritsyan, Acting Manager, Performance Measurement, Ontario Health (Quality), Toronto, ON.

Naushaba Degani, Director, Quality Improvement, Canadian Mental Health Association, Ontario Division, Toronto, ON.

Sharon Gushue, Senior Methodologist, Evaluation, Ontario Health (Quality), Toronto, ON.

References

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). 2012. Pan-Canadian Primary Health Care Indicator Update Report. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?locale=en&pf=PFC2000>.

- Doctors of BC. 2019, March. MSPQI – Creating Quality Improvement Measurements that Empower Physicians. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.doctorsofbc.ca/news/mspqi-creating-quality-improvement-measurements-empower-physicians>.

- Government of Northwest Territories. 2018, October. Annual Report 2017-2018: NWT Health and Social Services System Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/hss/files/resources/hss-annual-report-2017-18.pdf>.

- Haj-Ali W., Hutchison B.. 2017. Establishing a Primary Care Performance Measurement Framework for Ontario. Healthcare Policy 12(3): 66–79. 10.12927/hcpol.2017.25026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Data Coalition. 2019. About Us: Our Story. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://hdcbc.ca/about-us/>.

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. 2019a, March. Primary Care Patient Experience Survey – Physician Report Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqca.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Dr.-Sample-Physician-Report-Final-JB.pdf>.

- Health Quality Council of Alberta. 2019b, March. New Primary Care Patient Experience Information on FOCUS on Primary Healthcare Website. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqca.ca/news/2019/03/hqca-adds-new-primary-care-patient-experience-info-to-focus-on-primary-healthcare-website/>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2014. A Primary Care Performance Measurement Framework for Ontario: Report of the Steering Committee for the Ontario Primary Care Performance Measurement Initiative: Phase One Retrieved February 29, 2020. <http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/documents/pr/pc-performance-measurement-report-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2015a. Quality Matters: Realizing Excellent Care for All Retrieved February 29, 2020. <http://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/health-quality/realizing-excellent-care-for-all-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2015b. Quality in Primary Care: Setting a Foundation for Monitoring and Reporting in Ontario Retrieved January 30, 2020. <http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/Documents/pr/theme-report-quality-in-primary-care-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2015c. Patient Experience Survey Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/primary-care/primary-care-patient-experience-survey-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2016. Connecting the Dots for Patients: Family Doctors' Views on Coordinating Patient Care in Ontario's Health System Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/system-performance/connecting-the-dots-report-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2018a. Measuring Up 2018: A Yearly Report on How Ontario's Health System is Performing Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/pr/measuring-up-2018-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2018b. Primary Care Quality Advisory Committee Terms of Reference [unpublished]. Author.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2019a. Measuring Up 2019: A Yearly Report on How Ontario's Health System is Performing Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://hqontario.ca/Portals/0/Documents/pr/measuring-up-2019-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2019b, November 20. Re: Annual Priorities for the 2020/21 Quality Improvement Plans [annual memo]. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/qip/annual-memo-2020-2021-en.pdf>.

- Health Quality Ontario. 2020. MyPractice: Primary Care: A Tailored Report for Quality Care. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqontario.ca/Quality-Improvement/Practice-Reports/Primary-Care>.

- Ivers N.M., Maybee A. and Ontario Healthcare Implementation Laboratory Team. 2018. Engaging Patients to Select Measures for a Primary Care Audit and Feedback Initiative. CMAJ 190(Suppl 1): S42–S43. 10.1503/cmaj.180334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. 2015a, May. NWT Health and Social Services: Performance Measurement Framework Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/hss/files/performance-measurement-framework.pdf>.

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. 2015b, May. Public Performance Measures Report 2015: NWT Health and Social Services System Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/hss/files/nwt-hss-public-performance-measures-report-2015.pdf>.

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services. 2016, October. Public Performance Measures Report 2016: NWT Health and Social Services System. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hss.gov.nt.ca/sites/hss/files/resources/public-performance-measures-report-2016.pdf>.

- Nova Scotia Health Authority. 2019a, January. Patient Experience Survey Results 2017–18 Retrieved February 28, 2020. <https://www.nshealth.ca/sites/nshealth.ca/files/patient_experience_survey_results_2017-18.pdf>.

- Nova Scotia Health Authority. 2019b. Current State Assessment of the Primary Health Care System in Nova Scotia-Executive Summary Retrieved January 30, 2020. <http://www.nshealth.ca/sites/nshealth.ca/files/current-state-assessment-primary-health-care-system-nova-scotia-executive-summary.pdf>.

- Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. 2017. Community Health Centres. In Annual Report 2017 Volume 1 of 2 (pp. 180–223). Retrieved September 5, 2018. <http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en17/2017AR_v1_en_web.pdf>.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. 2019. The Health Care Experience Survey. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/healthcareexperiencesurvey.aspx>.

- Ontario Primary Care Reporting Alliance. 2019, February. Strategy Recommendations Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://www.hqontario.ca/Portals/0/documents/qi/primary-care/ontario-primary-care-reporting-alliance-strategy-en.pdf>.

- Saskatchewan Health Quality Council. 2017. Health System Performance: Measuring the Patient Experience. Retrieved January 30, 2020. <https://hqc.sk.ca/health-system-performance/measuring-the-patient-experience>.

- Yukon Government Health and Social Services. 2014, December. HSS Performance Measure Framework 2014–2019 Retrieved January 30, 2020. <http://www.hss.gov.yk.ca/pdf/hssperformansmeasure2014-2019.pdf>.