ABSTRACT

Synaptosomal associated protein of 23 kDa (SNAP23), a plasma membrane-localized soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE), is a ubiquitously expressed protein that is generally involved in fusion of the plasma membrane and secretory or endosomal recycling vesicles during several types of exocytosis. SNAP23 is expressed in phagocytes, such as neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells, and functions in both exocytosis and phagocytosis. This review focuses on the function of SNAP23 in immunoglobulin G Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis by macrophages. SNAP23 and its partner SNAREs mediate fusion of the plasma membrane with intracellular organelles or vesicles to form phagosomes as well as the fusion of phagosomes with endosomes or lysosomes to induce phagosome maturation, characterized by reactive oxygen species production and acidification. During these processes, SNAP23 function is regulated by phosphorylation. In addition, microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3 (LC3)-associated phagocytosis, which tightly promotes or suppresses phagosome maturation depending on the foreign target, requires SNAP23 function. SNAP23 that is enriched on the phagosome membrane during LC3-associated phagocytosis may be phosphorylated or dephosphorylated, thereby enhancing or inhibiting subsequent phagosome maturation, respectively. These findings have increased our understanding of the SNAP23-associated membrane trafficking mechanism in phagocytes, which has important implications for microbial pathogenesis and innate and adaptive immune responses.

Keywords: MAP1LC3A, membrane fusion, phagocytosis, SNAP23 protein, SNARE proteins

Phagocytosis is a form of endocytosis that is largely observed in professional phagocytes, particularly neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells. During phagocytosis, foreign particles larger than 0.5 μm, including bacteria, yeast cells, cellular debris, and other immunoglobulin (Ig) G-opsonized or complement-opsonized targets, are recognized by various cell surface pattern recognition receptors on the phagocytes, and internalized.1, 2 For example, Fc receptors (FcRs) cluster at sites where they contact IgG-opsonized particles; this interaction activates a signaling cascade that induces cytoskeletal reorganization and extensive plasma membrane deformation, ultimately leading to engulfment of the particles. The newly formed phagosomes progressively mature into phagolysosomes by sequential fusion with endocytic compartments and lysosomes. During this process, the microbicidal NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) complex is assembled in early phagosomes to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), and vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) is recruited to the phagosome where it acidifies the phagosomal environment to promote lysosomal hydrolase activity.3,4,5 In some cases, when phagosomal acidification is relatively mild, remnant peptides from the particles can serve as antigens to be presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and/or class II molecules.6, 7 Phagocytosis is, therefore, an important process that contributes to host innate and adaptive immune responses against foreign particles.

Membrane fusion with intracellular vesicles and/or organelles, such as early and late endosomes, is triggered at both the foreign particle-attached site of the plasma membrane and the nascent phagosome.5, 8, 9 Phagosome formation and maturation are complicated processes that involve the fusion and fission of various types of membranes, and the molecular mechanisms are not yet fully understood. The purpose of this review is to highlight the function and regulation of synaptosomal-associated protein 23 kDa (SNAP23), a plasma membrane-localized soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE), in phagosome formation and maturation in macrophages, with a focus on our recent research.10, 11

SNARE PROTEINS INVOLVED IN PHAGOCYTOSIS

Fusion between two membranes, such as a vesicle and a target membrane, is mediated by SNAREs that extend from each membrane. SNARE proteins form complexes that are required for membrane fusion. These complexes contain coiled-coil bundles consisting of four helices, named for their conserved amino acid residues. Three of the helices (Qa-, Qb-, and Qc-SNARE motifs) are extended from one membrane by proteins of the syntaxin (stx) and SNAP25 families that contain a conserved glutamine residue at a central position called the zero layer. The fourth helix (R-SNARE motif) is extended from the opposite membrane by a protein of the vesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP, also called synaptobrevin) family that contains a conserved arginine residue at the same position. Proper assembly of the SNAREs (Qa, Qbc, and R) leads to formation of the SNARE complex, resulting in membrane fusion and cargo delivery, and/or content mixing (Fig. 1).12,13,14

Fig. 1.

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) and the SNARE complex. (A) Schematic representation of the SNARE family based on the central amino acid residue of the SNARE motif and the domain structure. (B) SNARE-mediated membrane fusion of target and vesicle membranes. VAMP, vesicle-associated membrane protein; TM, transmembrane domain.

When foreign particles are recognized by specific receptors on the plasma membrane, the phagosome-forming membrane is thought to originate not only from the invaginated plasma membrane, but also from intracellular vesicles and/or organelles such as endosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Inhibition of phagocytosis by microinjection of tetanus toxin light chain (a potent neurotoxin produced by Clostridium tetani) into macrophages revealed the involvement of SNARE in this process.15 During FcR-mediated phagocytosis, recycling endosome-localized VAMP3 (also called cellubrevin), a target of tetanus toxin light chain, accumulates around incomplete phagosomes that have not closed and is enriched in isolated early phagosomes, indicating that focal exocytosis of VAMP3-related vesicles is required for the onset of phagosome formation.16 VAMP3 also mediates exocytosis of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-containing vesicles at the plasma membrane at the site of phagocytic cup formation with the yeast, Candida albicans.17

Late endosome- or lysosome-localized VAMP7 (also called tetanus neurotoxin-insensitive VAMP or TI-VAMP) is required for FcR- or complement C3 receptor-mediated phagocytosis. Interestingly, as demonstrated by live-cell imaging experiments in macrophages, VAMP7 recruitment to a phagosome follows VAMP3 recruitment to the same phagosome.18 However, in dendritic cells, VAMP7 and late endosome-localized VAMP8 (also called endobrevin) are negative regulators of the phagocytosis of Escherichia coli.19 Unfortunately, because green fluorescent protein (GFP) is sensitive to the acidic pH of the phagosome, to use E. coli expressing GFP for evaluation of phagocytosis efficiency is problematic. Knockdown of plasma membrane-localized Qa-SNARE stx11 enhances the phagocytosis efficiency of primary human monocytes and macrophages for apoptotic cells and IgG-opsonized red blood cells.20 However, stx11 knockout does not affect phagocytosis in mouse macrophages.21 In addition, ER-localized SNAREs have been implicated in phagosome formation. Consistent with the inclusion of ER-derived membrane in the bottom of forming phagosomes, and the detection of ER-resident proteins via proteomic analyses of isolated phagosomes, ER-SNAREs, such as stx18, D12 (also called p31/Use1), and Sec22b have been detected on phagosomes.22,23,24,25 Overexpression and small interfering (si)RNA-based knockdown of these SNAREs demonstrated that, during FcR-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages, stx18 was involved in phagosome formation and was negatively regulated by Sec22b.22, 23

After internalizing foreign particles, the phagosome continuously fuses with vesicles and/or compartments related to endocytic organelles. The Qa-SNAREs, stx7 and stx13, are localized to late endosomes/lysosomes and recycling endosomes, respectively. They are required at distinct steps for the interaction of phagosomes with either endosomes or lysosomes during FcR-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages.26 On the other hand, VAMP8 may negatively regulate phagosome maturation in dendritic cells because knockdown of VAMP8 enhances the formation of phagolysosomes containing E. coli particles.19

INVOLVEMENT OF SNAP23 IN PHAGOCYTOSIS

Many SNAREs are involved in phagocytosis (Table 1). All SNAREs localize only to intracellular vesicles and/or organelles, but not all specific cognate SNARE partners on the plasma membrane and phagosomes have been determined. SNAP23 and the Qa-SNARE, stx4, are candidate partners of VAMP3 in phagocytosis associated with TNF-α secretion in macrophages.9, 17

Table 1. SNARE proteins that function during phagocytosis.

| SNARE type | SNARE protein | Localization | Function during phagocytosis | Immune cells | References |

| Qa-SNARE | syntaxin7 | LE/LY | phagosome maturation (promote) |

FcγRIIa-transfected COS-1 cells, macrophages |

26 |

| syntaxin11 | PM | phagosome formation (suppress or no involvement) |

macrophages | 20, 21 | |

| syntaxin13 | EE/RE | phagosome maturation (promote) |

FcγRIIa-transfected COS-1 cells, macrophages |

26 | |

| syntaxin18 | ER | phagosome formation (promote) |

macrophages | 22 | |

| Qc-SNARE | D12 (p31) | ER | phagosome formation (promote) |

macrophages | 22 |

| Qbc-SNARE | SNAP23 | PM | phagosome formation and maturation (dependent on phosphorylation) |

macrophages, dendritic cells |

10, 11 |

| R-SNARE | VAMP3 | RE | phagosome formation and maturation (promote) |

macrophages, dendritic cells |

16, 18 |

| VAMP7 | LE/LY | phagosome formation and maturation (promote) |

macrophages | 18 | |

| VAMP8 | LE/LY, RE | phagosome formation (suppress) |

dendritic cells | 19 | |

| Sec22b | ER, ERGIC | phagosome formation (suppress) |

macrophages | 23 |

EE, early endosome; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERGIC, ER-Golgi intermediate compartment; LE, late endosome; LY, lysosome; PM, plasma membrane; RE, recycling endosome.

Structure and general function of SNAP23

SNAP23, a ubiquitously expressed SNARE belonging to the SNAP25 (Qbc-SNARE) family, contains two coiled-coil SNARE motifs linked by a cysteine-rich region.14 Cysteine residues 79, 80, 83, and 87 in the cysteine-rich region are palmitoylated, which contributes to the membrane association of SNAP23 in mast cells.27 This palmitoylation requires a proline residue at position 119, which is similar to the palmitoyl acyltransferase DHHC17 recognition site in SNAP25.27, 28 SNAP23 is predominately expressed in many cells at the plasma membrane, where it mediates exocytosis of secretory vesicles and granules as well as SNAP25 does.29 However, in mast cells, IgE-mediated activation causes re-localization of SNAP23 from the plasma membrane to internal secretory granule membranes for compound exocytosis where the vesicles either fuse with each other in advance of plasma membrane fusion (multivesicular exocytosis) or in a sequential manner (sequential exocytosis).30 In neutrophils, SNAP23 mainly localizes to cytoplasmic granules, such as specific granules and gelatinase-rich tertiary granules, and is involved in membrane fusion between specific granules and phagosomes.31,32,33 In neurons, SNAP23 localizes to postsynaptic spines and regulates the transport of the glutamate NMDA receptor to the cell surface.34 Recently, we found that SNAP23 regulates stimulus-dependent Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 trafficking to the cell surface in macrophages by cooperating with stx11.35

Phagosome formation

SNAP23 is a plasma membrane-localized candidate partner for endosomal and ER-localized SNAREs involved in phagosome formation although its specific function has not been determined. To determine the function of SNAP23 in phagocytosis, we established a murine J774 macrophage line that stably expressed SNAP23 N-terminally fused to the fluorescence protein, monomeric Venus: J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells.10 In these cells, mVenus-SNAP23 was expressed at almost twice the level of endogenous SNAP23, and, like endogenous SNAP23, it mainly localized to the plasma membrane. When IgG-opsonized zymosan (a yeast cell wall component) particles were incubated with J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells, mVenus-SNAP23 localized to phagosomes containing zymosan. J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells had greater IgG-opsonized zymosan uptake efficiency than the control cells, whereas siRNA-mediated SNAP23 knockdown decreased uptake. Overexpression of mVenus-SNAP23 also enhanced uptake efficiency for E. coli, which is recognized by TLR4 and CD36,36 and non-opsonized zymosan, which is recognized by TLR2 and Dectin-1 (our unpublished data). These results indicate that SNAP23 functions broadly in phagosome formation in macrophages during general receptor-mediated phagocytosis, not only FcR-mediated phagocytosis. For example, SNAP23 may cooperate with VAMP3-mediated TNF-α release during phagocytosis of C. albicans as a partner SNARE.17

Phagosome maturation

Phagosome maturation comprises several events within phagosomes, such as ROS production by the assembled NOX2 complex, acidification by V-ATPase, hydrolase acquisition, and antigen processing for the generation of MHC class II complexes.3, 37, 38 Phagosome maturation, which is caused by membrane fusion between phagosomes and endosomes or the ER, is regulated by Rab small GTPases, such as Rab5, Rab7, and Rab27a.37, 39 To investigate the role of SNAP23 in phagosome maturation, we added IgG-opsonized latex beads to J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells to promote phagosome formation. Then, we collected phagosomes at different maturation levels over time by centrifugation in discontinuous sucrose gradients. Western blot analyses of the phagosome fractions showed that gp91phox and p22phox (NOX2 complex components), late endosome-/lysosome-localized LAMP-1, and the lysosome-related organelle-localized a3 subunit of V-ATPase were enriched at earlier times in J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells as compared to the control cells. To analyze the phagosomal environment, the cells were treated with LysoTracker™ Red DND-99 dye, a weak base conjugated to a red fluorophore, which accumulates in acidic organelles and can be observed under a microscope. The number of LysoTracker-positive phagosomes was higher in J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells than in control cells, which suggested that J774/mVenus-SNAP23 cells contained more mature phagosomes. We also examined the effect of transfection with SNAP23 siRNA on phagosome–lysosome fusion in J774 cells, in which late endosomes and lysosomes were pre-labeled with rhodamine B-conjugated dextran (RB-dextran). The number of RB-dextran–positive phagosomes produced by the fusion of phagosomes and late endosomes or lysosomes was lower in cells transfected with SNAP23 siRNA than in cells treated with control siRNA. This reduction in RB-dextran–positive phagosomes was prevented by transfection with an siRNA-resistant SNAP23 construct. These results strongly suggest that SNAP23 is involved in phagosome maturation during FcR-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages.10

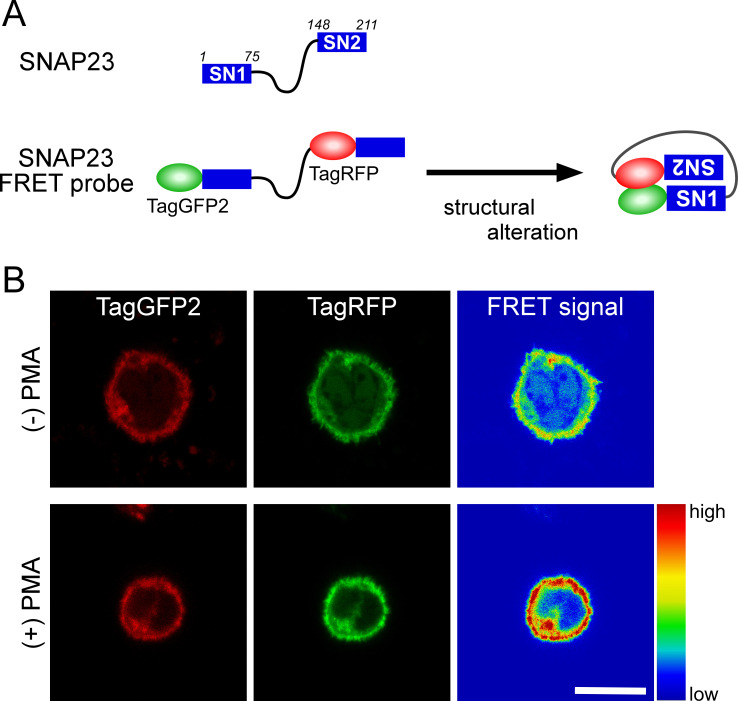

Although SNAP23 localizes to phagosomes and its expression level affects phagosome maturation, it is not clear if SNAP23 functions on phagosomes. Given that SNAP23 should undergo a structural change to form a SNARE complex during membrane fusion, we designed an intramolecular Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) probe for SNAP23.10 SNAP23 contains two SNARE motifs, SN1 (1–75) and SN2 (148–211); the N-terminal regions of these motifs move closer together during SNARE complex formation with adequate SNARE partners.13 On the basis of the previously reported design of a SNAP25 FRET probe,40, 41 we constructed a SNAP23 FRET probe with TagGFP2 donor and TagRFP (red fluorescent) acceptor fluorescence probes at the N-termini of SN1 and SN2, respectively (Fig. 2A). If SNAP23 functioned in membrane fusion during phagosome maturation, it would undergo a structural alteration bringing the folded N-terminal domains of SN1 and SN2 into close proximity within a SNARE complex, thereby enhancing the FRET signal from the probe on the phagosome membrane (Fig. 2A). On phagosomes containing IgG-opsonized zymosan, the enhanced FRET signal from the transiently expressed SNAP23 FRET probe was detected only when Myc-tagged VAMP7 was co-expressed. These results strongly suggested that SNAP23 on phagosomes functions, at least in fusion with late endosomes and/or lysosomes, by cooperating with VAMP7 as a SNARE partner.10

Fig. 2.

Analysis of an intramolecular FRET probe of synaptosomal-associated protein of 23 kDa (SNAP23). (A) Schematic representation of SNAP23 and its FRET probe. The predicted conformation of the SNAP23-based FRET construct upon structural alteration by forming adequate SNARE complexes during phagocytosis. (B) FRET imaging analyses using J774 cells transiently expressing the SNAP23 probe. TagGFP and TagRFP images were captured on a confocal microscope using excitation-emission wavelengths of 488‒522 and 561‒632 nm, respectively. FRET ratio signals were determined on a pixel-by-pixel basis by division of the TagRFP images by the TagGFP2 images, and are shown as pseudo-color images. High FRET ratios were observed in the presence of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) at a final concentration of 100 ng/mL. Bar, 10 μm.

REGULATORY MECHANISM OF SNAP23 IN PHAGOCYTOSIS

Like SNAP25, SNAP23 generally mediates the exocytosis of secretory vesicles upon phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of SNAP23 occurs at Ser23/Thr24 and Ser161 in human thrombin-activated platelets, and at Ser95 and Ser120 within the linker domain in rat mast cells.42,43,44 In mouse mast cells stimulated via the high-affinity IgE receptor, phosphorylation of SNAP23 at Ser95 and Ser120 is mediated by IκB kinase 2 (IKK2) and induces degranulation.44 IKK2 is also required for the function of activated platelets and the regulation of platelet exocytosis via SNAP23 phosphorylation at Ser95.45 Although, in many cases, SNAP23 phosphorylation promotes exocytosis by augmenting SNARE complex assembly, Ca2+-dependent exocytosis in rat astrocytes is suppressed by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), an activator of protein kinase C, which is another candidate kinase for SNAP23 phosphorylation.46 Our data suggest that the function of SNAP23 in phagosome formation and maturation is regulated by a protein modification, presumably phosphorylation. As SNAP23 Ser95, which is positioned in the linker close to the palmitoylated cysteines, is conserved between humans and rodents, we investigated the role of phosphorylation at this site in phagocytosis.11

Effect of SNAP23 phosphorylation at Ser95 on phagocytosis

To elucidate the role of the phosphorylation of SNAP23 at Ser95 in phagocytosis, we established J774 macrophages that stably expressed mVenus-tagged SNAP23 proteins with either a nonphosphorylatable S95A mutant or a phosphomimetic S95D mutant at levels similar to those of the wild-type protein.11 J774 cells overexpressing mVenus-SNAP23-S95D displayed lower phagocytosis efficiency for IgG-opsonized zymosan than the control mVenus-expressing cells. In contrast, cells overexpressing mVenus-SNAP23-wild type and mVenus-SNAP23-S95A had similarly higher efficiencies than the control cells. mVenus-SNAP23-S95D cells also had lower fusion efficiency for phagosomes containing IgG-opsonized zymosan and late endosomes, or lysosomes labeled with RB-dextran than cells expressing mVenus-SNAP23-wild type or mVenus-SNAP23-S95A.

PMA treatment of macrophages induces phosphorylation of SNAP23 at Ser95 in macrophages and reduces their phagocytosis efficiency for IgG-opsonized zymosan. In the presence of PMA, we observed an enhanced FRET signal from the SNAP23-wild type FRET probe on the plasma membrane (Fig. 2B), but not from the SNAP23-S95A probe. Interestingly, the SNAP23-S95D probe had constitutively high FRET signal intensity, independent of PMA treatment. This enhanced FRET signal may result from the formation of a compact structure of SNAP23-S95D interacting with a factor on the membrane. Thus, the compactly formed SNAP23-S95D mutant may inhibit proper SNARE complex formation with other SNARE proteins involved in phagocytosis. These results indicate that SNAP23 phosphorylated at Ser95 suppresses phagosome formation and maturation during FcR-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages.11

Phosphorylated SNAP23 regulates phagosome maturation

We next investigated which kinase was responsible for the phosphorylation of SNAP23 at Ser95 during phagocytosis. Because IKK2 phosphorylates SNAP23 at Ser95 to enhance secretion in mast cells and platelets, and to initiate the recruitment of MHC class I components to the phagosome from the endocytic recycling compartment in dendritic cells,47 we performed FRET analysis to assess whether IKK2 was involved in the phosphorylation of SNAP23 in macrophages. The FRET signal from the SNAP23-wild type probe on the plasma membrane was not enhanced by co-expression of Myc-IKK2, whereas the signal from the probe on the phagosome containing IgG-opsonized zymosan was enhanced. This enhancement was inhibited in the presence of SC-514, a specific inhibitor of IKK2, and was not detected on phagosomes in J774 cells co-expressing the SNAP23-S95A probe and Myc-IKK2, indicating that Myc-IKK2 phosphorylates Ser95 and induces structural changes in phagosome-associated SNAP23. Consistent with the results of overexpressing mVenus-SNAP23-S95D, overexpression of Myc-IKK2 inhibited phagosome–lysosome fusion, as indicated by suppression of RB-dextran accumulation in phagosomes from the late endosomes/lysosomes.11

During phagosome maturation, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), a key cytokine in the induction of the tumoricidal M1 phenotype, enhances ROS production and suppresses phagosomal acidification.48, 49 To clarify the role of phosphorylated SNAP23 in phagosome maturation under physiological conditions, we performed FRET analysis with SNAP23 probes in IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages. In IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages, we observed an enhanced FRET signal from the SNAP23-wild type probe on the phagosome during FcR-mediated phagocytosis, but not from the SNAP23-S95A probe. This enhancement was inhibited in the presence of SC-514. Furthermore, stimulation with IFN-γ suppressed the fusion efficiency between phagosomes and late endosomes/lysosomes, which was rescued in the presence of SC-514. These results strongly suggest that SNAP23 on phagosomes in IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages is phosphorylated at Ser95 by IKK2, resulting in the suppression of phagosome maturation.11

These early studies focused on canonical phagocytosis. We later explored the role of SNAP23 in phagocytosis associated with microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3 (LC3) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Function and regulation of synaptosomal-associated protein of 23 kDa (SNAP23) in canonical phagocytosis and LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP). During Fc receptor (FcR)-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages, phagosome formation and maturation are promoted by SNAP23, but suppressed by SNAP23 phosphorylation at Ser95. Membrane occupation and recognition nexus repeat-containing-2 (MORN2) enhances the recruitment of SNAP23 to the formed phagosome containing foreign particles and subsequent LAP. SNAP23 promotes phagosomal reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by assembling NOX2 components. Phagosomal ROS induce the recruitment of LC3 to phagosomes (LAPosome formation). LC3-II may maintain SNAP23 on the phagosomes to enhance or suppress the fusion of LAPosomes with endocytic compartments. Precisely, enriched SNAP23 may be able to tightly regulate LAPosome maturation by its phosphorylation status depending on foreign particles. IKK2, IκB kinase 2.

ROLE OF SNAP23 IN LC3-ASSOCIATED PHAGOCYTOSIS MEDIATED BY MEMBRANE OCCUPATION AND RECOGNITION NEXUS REPEAT-CONTAINING-2 (MORN2)

LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP): a noncanonical autophagy

LAP is a type of phagocytosis that involves phagosomes decorated with LC3. LAP is activated by various pattern recognition receptors, such as TLRs, Dectin-1, T-cell immunoglobulin- and mucin-domain-containing 4 (TIM4), and FcRs, and promotes the bactericidal activity and subsequent maturation of phagosomes.50 In some cases, LAP suppresses phagosome maturation and enhances the recruitment of MHC class II molecules to phagosomes, thereby promoting the presentation of target-derived peptides.6, 7 In contrast to canonical autophagy, LAP utilizes phagosomes with a single lipid bilayer and does not require ULK1 and/or ULK2, FIP200, ATG13, or ATG101, which are essential for canonical autophagy, although it uses other common autophagy-related proteins.51, 52 Phagosomal recruitment of phosphatidylethanolamine-conjugated LC3 (LC3-II) requires ROS production by the NOX2 complex; however, ROS production is dispensable for canonical autophagy.53 Therefore, LAP is considered a non-canonical form of autophagy. LAP has been the subject of several recent reviews.54,55,56 However, the regulatory mechanism underlying its function has not been fully elucidated.

The function of mammalian MORN2 in LAP

Mammalian MORN2 consists of 79 amino acid residues containing two MORN motifs; it is involved in the elimination of bacteria, such as Legionella pneumophila, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, through the enhancement of LAP efficiency in macrophages.57 In addition, J774 cells overexpressing mVenus-MORN2 (J774/mVenus-MORN2) produce LC3-II and form LAP phagosomes (LAPosomes) upon engulfment of E. coli and non-opsonized zymosan, respectively. The efficiency of LAPosome formation is significantly lower in the presence of the NOX2-selective inhibitor, diphenyleneiodonium in J774/mVenus-MORN2 cells. Interestingly, the efficiency of fusion between the phagosome, or LAPosome, and late endosomes/lysosomes in J774/mVenus-MORN2 cells is lower than that in control J774/mVenus cells, and this suppression is restored by diphenyleneiodonium. These results suggest that MORN2-mediated LAP is sensitive to ROS production and negatively regulates the maturation of phagosomes containing non-opsonized targets.58

MORN2 enhances SNAP23 recruitment to phagosomes

Because SNAP23 regulates ROS production via NOX2 complex formation on both the plasma membrane and phagosomes,10 we investigated if SNAP23 was involved in MORN2-mediated LAP in macrophages.58 Knockdown of SNAP23 in J774/mVenus-MORN2 cells lowered the efficiency of LAPosome formation. In addition, overexpression of SNAP23 in J774/mVenus-MORN2 cells enhanced LAPosome formation efficiency, but this enhancement was suppressed in the presence of diphenyleneiodonium. Because SNAP23 is responsible for ROS production within the phagosome,10 its localization to the phagosome could be increased during MORN2-mediated LAP. Therefore, we compared immunofluorescent anti-Myc antibody signals around the phagosome in J774 cells expressing control Myc-SNAP23/mVenus and Myc-SNAP23/mVenus-MORN2. As expected, phagosomes with high Myc signals were more abundant in J774/Myc-SNAP23/mVenus-MORN2 cells. Interestingly, this enhancement was not changed by the presence of diphenyleneiodonium. This indicated that the enhanced recruitment of SNAP23 to the phagosome preceded ROS production. Indeed, phagosomal ROS production was higher in J774/Myc-SNAP23/mVenus-MORN2 cells than in control cells. Immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that Myc-SNAP23 interacted with mVenus-MORN2. These results suggest that, in the case of non-opsonized targets, MORN2 interacts with SNAP23 to enhance recruitment to phagosomes, resulting in enhanced ROS production and LC3 localization (Fig. 3).58

CONCLUSION

Depending on the foreign particle and its specific receptor, phagocytosis is caused by many cellular alterations, such as cytoskeletal rearrangement, membrane deformation, and metabolism of phosphoinositides. We focused on the underlying regulatory mechanisms of membrane trafficking, especially SNARE protein SNAP23-mediated trafficking. SNAP23 is a central SNARE indispensable for phagocytosis. In particular, SNAP23 helps form the phagosome engulfing the target and is also involved in subsequent phagosome maturation.10 The SNARE complex with SNAP23 is likely assembled via a series of reactions that are regulated, at least in part, by the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of SNAP23. Phagosome formation and maturation during FcR-mediated phagocytosis are suppressed or delayed in macrophages overexpressing a phosphomimetic SNAP23 mutant11; however, engulfment of other targets, such as E. coli and non-opsonized zymosan, are better in these cells (our unpublished data). If IgG-opsonized and non-opsonized targets (which are more dangerous for the host) are present in the same environment, phosphorylated SNAP23 may be able to preferentially engulf the latter by suppressing FcR-mediated phagocytosis. Phosphorylation of SNAP23 by IKK2 in IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages contributes to the delayed fusion of phagosomes containing IgG-opsonized targets with late endosomes or lysosomes, presumably leading to the upregulation of antigen processing for MHC class I and/or II.11 In dendritic cells, TLR4 signaling during phagocytosis causes phosphorylation of SNAP23 at Ser95 and enhances phagosome fusion with the endocytic recycling compartment, which is a source of MHC class I molecules.47 In the near future, it will be important to rigorously study the phosphorylation of not only SNAP23, but also its partner SNAREs, and to identify the enzymes involved in phosphorylation and dephosphorylation.

Because LAP is generally a low-efficiency mode of phagocytosis, based on the total number of phagosomes formed,50, 53 the macrophage line overexpressing MORN2, which enhances the efficiency of LAPosome formation approximately three-fold, is a useful tool to understand the regulatory mechanism of LAP. Using this cell line, we found that the recruitment of SNAP23 to phagosomes was enhanced during LAP, leading to the enhanced ROS production essential for phagosomal localization of LC3-II.58 The interaction between the palmitoyl group of SNAP23 and the phosphatidylethanolamine of LC3-II may stabilize the membrane localization of both the molecules. The enrichment of phosphorylated or dephosphorylated SNAP23 on the phagosome may be advantageous for tightly controlled regulation of phagosome maturation. This hypothesis may explain differences in the progression of phagosome maturation based on the nature of the foreign target during LAP (Fig. 3). At present, both when and how SNAP23 is regulated by MORN2 and the relationship between SNAP23 and LC3-II in macrophages are unknown. In the future, clarifying the regulation of SNAP23 phosphorylation during phagocytosis and the detailed regulatory mechanism of SNAP23 by MORN2 will greatly contribute to the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases caused.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments: We thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for their help with English language editing.

This work was supported financially in part, by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (#22570189 and #20K06641 to K.H.) and Young Scientists and Early-Career Scientists grants (#25860218 and #19K16519, respectively, to C.S.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science as well as by a grant from the Takeda Science Foundation to C.S.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jutras I,Desjardins M. Phagocytosis: at the crossroads of innate and adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:511-27. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.102755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underhill DM,Goodridge HS. Information processing during phagocytosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:492-502. 10.1038/nri3244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freeman SA,Grinstein S. Phagocytosis: receptors, signal integration, and the cytoskeleton. Immunol Rev. 2014;262:193-215. 10.1111/imr.12212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haas A. The phagosome: compartment with a license to kill. Traffic. 2007;8:311-30. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00531.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swanson JA. Shaping cups into phagosomes and macropinosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:639-49. 10.1038/nrm2447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J,Becker C,Lowell CA,Underhill DM. Dectin-1-triggered recruitment of light chain 3 protein to phagosomes facilitates major histocompatibility complex class II presentation of fungal-derived antigens. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:34149-56. 10.1074/jbc.M112.382812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romao S,Gasser N,Becker AC,Guhl B,Bajagic M,Vanoaica D,et al. Autophagy proteins stabilize pathogen-containing phagosomes for prolonged MHC II antigen processing. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:757-66. 10.1083/jcb.201308173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egami Y. Molecular imaging analysis of Rab GTPases in the regulation of phagocytosis and macropinocytosis. Anat Sci Int. 2016;91:35-42. 10.1007/s12565-015-0313-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stow JL,Manderson AP,Murray RZ SNAREing immunity: the role of SNAREs in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:919-29. 10.1038/nri1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sakurai C,Hashimoto H,Nakanishi H,Arai S,Wada Y,Sun-Wada GH,et al. SNAP-23 regulates phagosome formation and maturation in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:4849-63. 10.1091/mbc.e12-01-0069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sakurai C,Itakura M,Kinoshita D,Arai S,Hashimoto H,Wada I,et al. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 at Ser95 causes a structural alteration and negatively regulates Fc receptor–mediated phagosome formation and maturation in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2018;29:1753-62. 10.1091/mbc.E17-08-0523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fasshauer D,Sutton RB,Brunger AT,Jahn R. Conserved structural features of the synaptic fusion complex: SNARE proteins reclassified as Q- and R-SNAREs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15781-6. 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutton RB,Fasshauer D,Jahn R,Brunger AT. Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 Å resolution. Nature. 1998;395:347-53. 10.1038/26412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahn R,Scheller RH SNAREs— engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631-43. 10.1038/nrm2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hackam DJ,Rotstein OD,Sjolin C,Schreiber AD,Trimble WS,Grinstein S. v-SNARE-dependent secretion is required for phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11691-6. 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bajno L,Peng XR,Schreiber AD,Moore HP,Trimble WS,Grinstein S. Focal exocytosis of VAMP3-containing vesicles at sites of phagosome formation. J Cell Biol. 2000;149:697-706. 10.1083/jcb.149.3.697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray RZ,Kay JG,Sangermani DG,Stow JL. A role for the phagosome in cytokine secretion. Science. 2005;310:1492-5. 10.1126/science.1120225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V,Fraisier V,Raposo G,Hurbain I,Sibarita JB,Chavrier P,et al. TI-VAMP/VAMP7 is required for optimal phagocytosis of opsonised particles in macrophages. EMBO J. 2004;23:4166-76. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho YHS,Cai DT,Wang CC,Huang D,Wong SH. Vesicle-associated membrane protein-8/endobrevin negatively regulates phagocytosis of bacteria in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:3148-57. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S,Ma D,Wang X,Celkan T,Nordenskjld M,Henter JI,et al. Syntaxin-11 is expressed in primary human monocytesmacrophages and acts as a negative regulator of macrophage engulfment of apoptotic cells and IgG-opsonized target cells. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:469-79. 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.D’Orlando O,Zhao F,Kasper B,Orinska Z,Müller J,Hermans-Borgmeyer I,et al. Syntaxin 11 is required for NK and CD8 + T-cell cytotoxicity and neutrophil degranulation. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:194-208. 10.1002/eji.201142343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatsuzawa K,Tamura T,Hashimoto H,Hashimoto H,Yokoya S,Miura M,et al. Involvement of syntaxin 18, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized SNARE protein, in ER-mediated phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3964-77. 10.1091/mbc.e05-12-1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hatsuzawa K,Hashimoto H,Hashimoto H,Arai S,Tamura T,Higa-Nishiyama A,et al. Sec22b is a negative regulator of phagocytosis in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4435-43. 10.1091/mbc.e09-03-0241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cebrian I,Visentin G,Blanchard N,Jouve M,Bobard A,Moita C,et al. Sec22b regulates phagosomal maturation and antigen crosspresentation by dendritic cells. Cell. 2011;147:1355-68. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Campbell-Valois FX,Trost M,Chemali M,Dill BD,Laplante A,Duclos S,et al. Quantitative proteomics reveals that only a subset of the endoplasmic reticulum contributes to the phagosome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111.016378. 10.1074/mcp.M111.016378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Collins RF,Schreiber AD,Grinstein S,Trimble WS. Syntaxins 13 and 7 function at distinct steps during phagocytosis. J Immunol. 2002;169:3250-6. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.6.3250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Agarwal V,Naskar P,Agasti S,Khurana GK,Vishwakarma P,Lynn AM,et al. The cysteine-rich domain of synaptosomal-associated protein of 23 kDa (SNAP-23) regulates its membrane association and regulated exocytosis from mast cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2019;1866:1618-33. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2019.06.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greaves J,Prescott GR,Fukata Y,Fukata M,Salaun C,Chamberlain LH. The hydrophobic cysteine-rich domain of SNAP25 couples with downstream residues to mediate membrane interactions and recognition by DHHC palmitoyl transferases. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1845-54. 10.1091/mbc.e08-09-0944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kádková A,Radecke J,Sørensen JB. The SNAP-25 Protein Family. Neuroscience. 2019;420:50-71. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2018.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein O,Roded A,Zur N,Azouz NP,Pasternak O,Hirschberg K,et al. Rab5 is critical for SNAP23 regulated granule-granule fusion during compound exocytosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15315. 10.1038/s41598-017-15047-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martín-Martín B,Nabokina SM,Blasi J,Lazo PA,Mollinedo F. Involvement of SNAP-23 and syntaxin 6 in human neutrophil exocytosis. Blood. 2000;96:2574-83. 10.1182/blood.V96.7.2574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mollinedo F,Calafat J,Janssen H,Martín-Martín B,Canchado J,Nabokina SM,et al. Combinatorial SNARE complexes modulate the secretion of cytoplasmic granules in human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2006;177:2831-41. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uriarte SM,Rane MJ,Luerman GC,Barati MT,Ward RA,Nauseef WM,et al. Granule exocytosis contributes to priming and activation of the human neutrophil respiratory burst. J Immunol. 2011;187:391-400. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suh YH,Terashima A,Petralia RS,Wenthold RJ,Isaac JTR,Roche KW,et al. A neuronal role for SNAP-23 in postsynaptic glutamate receptor trafficking. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:338-43. 10.1038/nn.2488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinoshita D,Sakurai C,Morita M,Tsunematsu M,Hori N,Hatsuzawa K. Syntaxin 11 regulates the stimulus-dependent transport of Toll-like receptor 4 to the plasma membrane by cooperating with SNAP-23 in macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2019;30:1085-97. 10.1091/mbc.E18-10-0653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morita M,Sawaki K,Kinoshita D,Sakurai C,Hori N,Hatsuzawa K. Quantitative analysis of phagosome formation and maturation using an Escherichia coli probe expressing a tandem fluorescent protein. J Biochem. 2017;162:309-16. 10.1093/jb/mvx034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mantegazza AR,Magalhaes JG,Amigorena S,Marks MS. Presentation of phagocytosed antigens by MHC class I and II. Traffic. 2013;14:135-52. 10.1111/tra.12026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pauwels AM,Trost M,Beyaert R,Hoffmann E. Patterns, Receptors, and Signals: Regulation of Phagosome Maturation. Trends Immunol. 2017;38:407-22. 10.1016/j.it.2017.03.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seto S,Tsujimura K,Koide Y. Rab GTPases regulating phagosome maturation are differentially recruited to mycobacterial phagosomes. Traffic. 2011;12:407-20. 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01165.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L,Bittner MA,Axelrod D,Holz RW. The structural and functional implications of linked SNARE motifs in SNAP25. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3944-55. 10.1091/mbc.e08-04-0344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takahashi N,Hatakeyama H,Okado H,Noguchi J,Ohno M,Kasai H SNARE conformational changes that prepare vesicles for exocytosis. Cell Metab. 2010;12:19-29. 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Polgár J,Lane WS,Chung SH,Houng AK,Reed GL. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 in activated human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44369-76. 10.1074/jbc.M307864200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hepp R,Puri N,Hohenstein AC,Crawford GL,Whiteheart SW,Roche PA. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 regulates exocytosis from mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6610-20. 10.1074/jbc.M412126200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki K,Verma IM. Phosphorylation of SNAP-23 by IkappaB kinase 2 regulates mast cell degranulation. Cell. 2008;134:485-95. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karim ZA,Zhang J,Banerjee M,Chicka MC,Al Hawas R,Hamilton TR,et al. IκB kinase phosphorylation of SNAP-23 controls platelet secretion. Blood. 2013;121:4567-74. 10.1182/blood-2012-11-470468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yasuda K,Itakura M,Aoyagi K,Sugaya T,Nagata E,Ihara H,et al. PKC-dependent inhibition of CA2+-dependent exocytosis from astrocytes. Glia. 2011;59:143-51. 10.1002/glia.21083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nair-Gupta P,Baccarini A,Tung N,Seyffer F,Florey O,Huang Y,et al. TLR signals induce phagosomal MHC-I delivery from the endosomal recycling compartment to allow cross-presentation. Cell. 2014;158:506-21. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Trost M,English L,Lemieux S,Courcelles M,Desjardins M,Thibault P. The phagosomal proteome in interferon-gamma-activated macrophages. Immunity. 2009;30:143-54. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Canton J,Khezri R,Glogauer M,Grinstein S. Contrasting phagosome pH regulation and maturation in human M1 and M2 macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25:3330-41. 10.1091/mbc.e14-05-0967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanjuan MA,Dillon CP,Tait SWG,Moshiach S,Dorsey F,Connell S,et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450:1253-7. 10.1038/nature06421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez J,Almendinger J,Oberst A,Ness R,Dillon CP,Fitzgerald P,et al. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha (LC3)-associated phagocytosis is required for the efficient clearance of dead cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17396-401. 10.1073/pnas.1113421108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 52.Martinez J,Malireddi RKS,Lu Q,Cunha LD,Pelletier S,Gingras S,et al. Molecular characterization of LC3-associated phagocytosis reveals distinct roles for Rubicon, NOX2 and autophagy proteins. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:893-906. 10.1038/ncb3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 53.Huang J,Canadien V,Lam GY,Steinberg BE,Dinauer MC,Magalhaes MAO,et al. Activation of antibacterial autophagy by NADPH oxidases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6226-31. 10.1073/pnas.0811045106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez J. LAP it up, fuzz ball: a short history of LC3-associated phagocytosis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;55:54-61. 10.1016/j.coi.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Heckmann BL,Green DR Correction: LC3-associated phagocytosis at a glance (). J Cell Sci. 2019;132. 10.1242/jcs.222984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Upadhyay S,Philips JA LC3-associated phagocytosis: host defense and microbial response. Curr Opin Immunol. 2019;60:81-90. 10.1016/j.coi.2019.04.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abnave P,Mottola G,Gimenez G,Boucherit N,Trouplin V,Torre C,et al. Screening in planarians identifies MORN2 as a key component in LC3-associated phagocytosis and resistance to bacterial infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:338-50. 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morita M,Kajiye M,Sakurai C,Kubo S,Takahashi M,Kinoshita D,et al. Characterization of MORN2 stability and regulatory function in LC3-associated phagocytosis in macrophages. Biol Open. 2020;9;bio051029. 10.1242/bio.051029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]