Abstract

The management of intra-ocular pressure (IOP) is important for glaucoma treatment. IOP is recognized for showing seasonal fluctuation. Glaucoma patients can be at high risk of dry eye disease (DED). We thus evaluated seasonal variation of IOP with and without DED in glaucoma patients. This study enrolled 4,708 patients, with mean age of 55.2 years, who visited our clinics in Japan from Mar 2015 to Feb 2017. We compared the seasonal variation in IOP (mean ± SD) across spring (March–May), summer (June–August), fall (September–November), and winter (December–February). IOP was highest in winter and lowest in summer, at 14.2/13.7 for non-glaucoma without DED group (n = 2,853, P = 0.001), 14.5/13.6 for non-glaucoma with DED group (n = 1,500, P = 0.000), 14.0/13.0 for glaucoma without DED group (n = 240, P = 0.051), and 15.4/12.4 for glaucoma with DED group (n = 115, P = 0.015). Seasonal variation was largest across the seasons in the glaucoma with DED group. IOP was also inversely correlated with corneal staining score (P = 0.000). In conclusion, the seasonal variation was significant in most of study groups and IOP could tend to be low in summer.

Subject terms: Corneal diseases, Glaucoma

Introduction

Glaucoma is the second leading cause of blindness worldwide1. Elevated intra-ocular pressure (IOP) is the only adaptable risk factor for glaucoma and the progression of visual field loss is strongly related to IOP. The management of glaucoma aims to reduce IOP2,3, which could be influenced by various factors including blood pressure, body posture, and diurnal and seasonal variations4–6. Mean IOPs are reportedly higher in winter and lower in summer in both normal7–9 and glaucoma10,11 subjects, and the magnitude of these fluctuations are larger in patients with glaucoma than in normal subjects. Clinically, it is important to control IOP since a large diurnal fluctuation in IOP is a known risk factor for the progression of glaucoma12. Seasonal and diurnal fluctuations could thus mislead a clinical decision regarding medication and surgery. Although this seasonal pattern was described two decades ago, the phenomenon is not completely characterised8.

Due to the chronic nature of glaucoma, many affected patients experience long-term exposure to commercial pharmaceutical components and preservatives that are known to cause corneal and conjunctival toxicity13–15. Previous studies have shown that up to 40% of glaucoma patients use more than one topical medication16, and benzalkonium chloride (BAK), the most common preservative in anti-glaucoma solutions, has been strongly implicated in inducing and/or exacerbating ocular toxicity such as corneal epithelial cell dysfunction and inflammatory and toxic side effects on the conjunctiva. Consequently, glaucoma-affected patients can be at high risk of also developing the commonly seen dry eye disease (DED)17–19.

DED also exhibits seasonal fluctuations in vulnerability against environmental conditions. DED signs and symptoms tend to vary throughout the year, and particularly with seasonal changes across summer to winter8. These findings corroborate the influential factors including climate, sunlight, temperature, humidity and light. The pathophysiology of DED is complicated since it is multifactorial, and there is dissociation between signs and symptoms in DED20. For instance, immunological, neurological, and psychological comorbidities could enhance the effect of seasonality on DED8.

We thus sought to understand the contribution of DED to seasonal variations in IOP, and herein we evaluated seasonal variation of IOP with and without DED in glaucoma patients.

Results

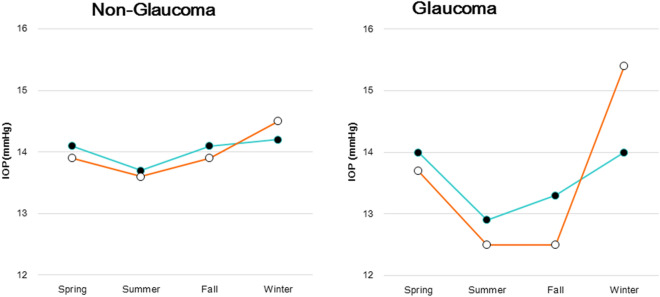

Table 1 details the 4,708 consecutive patients enrolled in this study, with 1,692 males and a mean age of 55.2 years. The patient ophthalmological results are also listed in Table 1. Prostaglandin analogues (PG) are a first-line medication that was prescribed for 80.5% of non-DED cases and 73.3% for DED cases in this study. The averaged numbers of glaucoma medications being administered in this study cohort were 1.4 ± 0.6 for those with DED and 1.4 ± 0.6 for non-DED group. There was no difference in the severity of glaucoma between non-DED and DED groups. IOP was highest in winter and lowest in summer in all groups (Fig. 1). The IOP (mmHg, mean ± SD) levels in winter/summer and the resulting seasonal variation (winter-summer) were 14.2 ± 3.1/13.7 ± 3.0 and 0.5 for the non-glaucoma non-DED group (P = 0.001) compared to 14.5 ± 3.2/13.6 ± 3.1 and 0.9 for the non-glaucoma with DED group (P = 0.000), and 14.0 ± 3.3/13.0 ± 3.1 and 1.0 for the glaucoma non-DED group (P = 0.051) compared to 15.4 ± 6.2/12.4 ± 2.7 and 3.0 for the glaucoma with DED group (P = 0.015).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and ophthalmological parameters.

| Non-glaucoma | Glaucoma | P value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-DED (n = 2,853) |

DED (n = 1,500) |

Non-DED (n = 240) |

DED (n = 115) |

||

| #(spring/summer/fall/winter) | 608/819/838/588 | 377/402/426/295 | 56/82/62/60 | 23/30/28/34 | |

| Age (year) | 54.9 ± 18.6 | 53.3 ± 17.6 | 65.5 ± 13.7 | 63.2 ± 14.8 | n.s |

| % male | 42.3 | 19.6 | 56.3 | 37.1 | < 0.001* |

| Refractive errors (diopter) | − 2.35 ± 3.14 | − 2.49 ± 3.20 | − 2.63 ± 3.52 | − 3.12 ± 3.94 | n.s |

| Mean IOP (mmHg) | 14.0 ± 3.00 | 13.9 ± 3.1 | 13.5 ± 3.3 | 13.6 ± 4.4 | n.s |

| Glaucoma parameters | |||||

| MD (dB) | – | – | − 5.11 ± 5.21 | − 5.04 ± 6.06 | n.s |

| Cupping (%) | – | – | 72.0 ± 17.9 | 73.3 ± 16.8 | n.s |

| GCC (μm) | – | – | 85.7 ± 19.5 | 87.3 ± 21.4 | n.s |

| Frequency of instillation | – | – | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | n.s |

| #of medication | – | – | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | n.s |

| Glaucoma medication (%) | |||||

| PG | – | – | 80.5 | 73.3 | n.s |

| Beta blocker | – | – | 8.4 | 21.6 | < 0.001 |

| Fix (PG/beta blocker) | – | – | 10.3 | 8.6 | n.s |

| Fix (beta blocker/CAI) | – | – | 12.3 | 14.8 | n.s |

| CAI | – | – | 9.6 | 11.2 | n.s |

| Others | – | – | 13.8 | 11.3 | n.s |

| DED parameters | |||||

| Corneal staining score | 0.21 ± 0.49 | 0.54 ± 0.74 | 0.37 ± 0.63 | 0.73 ± 0.82 | < 0.001 |

| BUT (s) | 5.40 ± 1.49 | 2.72 ± 1.02 | 5.07 ± 1.65 | 2.73 ± 1.07 | < 0.001 |

DED, dry eye disease; IOP, intra-ocular pressure; MD, mean deviation; GCC, thickness of ganglion cell complex; PG, prostaglandin analogue solution; Fix, fixed combination; CAI, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors BUT, tear break-up time; SPK, superficial punctate keratitis.

*P < 0.05, Non-DED versus DED with glaucoma, unpaired t test, or chi squared test as appropriate.

Figure 1.

Seasonal change in mean IOP for patients with and without DED. The non-glaucoma group showed small seasonal amplitudes in both the DED (open symbol) and non-DED (closed symbol) groups (left panel). Glaucoma patients showed apparently large seasonal amplitudes in both groups, but especially in the DED group (right panel). The amplitude of seasonal variation was significantly larger in glaucoma patients with DED than in those without DE (P = 0.002, two-factor mixed design with repeated measures on one factor) and the non-glaucoma group with DED (P = 0.020). IOP; intra-ocular pressure, DED; dry eye disease.

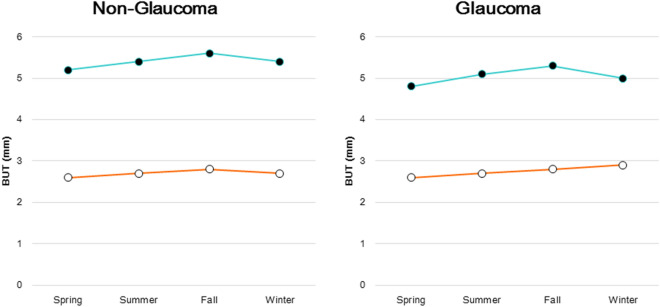

We conducted a two-way ANOVA for seasonal variation of IOP and found no significant difference between the non-glaucoma and non-DED group and the other three groups, and between the glaucoma and non-DED group and the other three groups (Table 2). The results of a one-way ANOVA indicated a significant seasonal variation in three groups. Regarding seasonal change of corneal staining score, the non-glaucoma group showed small seasonal amplitude changes with and without DED in both glaucoma groups, with the highest and lowest scores in fall and summer, respectively (Fig. 2). The glaucoma group showed apparently large seasonal amplitudes in both DED groups, with the peak of dry eye in summer and no dry eye in fall. Seasonal changes in BUT exhibited no obvious seasonal amplitude in any of the four groups (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

The results of analysis of variance (ANOVA).

| IOP (mmHg) | Seasons | Two-way ANOVA versus no glaucoma, non-DED | Two-way ANOVA versus Glaucoma, non-DED | One way ANOVA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | ||||

| No glaucoma, non-DED | 14.1 ± 2.9 | 13.7 ± 3.0 | 14.1 ± 2.9 | 14.2 ± 3.1 |

Season: F = 1.555, P = 0.362 Glaucoma: F = 9.741, P = 0.052 |

F = 11.972 P < 0.001 | |

| No glaucoma, DED | 13.9 ± 3.0 | 13.6 ± 3.1 | 13.9 ± 3.1 | 14.5 ± 3.1 |

Season: F = 0.703, P = 0.611 DED: F = 2.684, P = 0.200 |

Season: F = 0.720, P = 0.603 Glaucoma × DED: F = 4.246, P = 0.131 |

F = 4.470 P = 0.004 |

| Glaucoma, non-DED | 14.0 ± 3.7 | 13.0 ± 3.1 | 13.2 ± 3.2 | 13.0 ± 3.3 |

Season: F = 1.759, P = 0.327 Glaucoma: F = 0.069, P = 0.809 |

F = 1.781 P = 0.151 | |

| Glaucoma, DED | 13.7 ± 4.2 | 12.4 ± 2.7 | 14.1 ± 5.1 | 15.4 ± 6.2 |

Season: F = 1.930, P = 0.301 Glaucoma × DED: F = 0.058, P = 0.825 |

Season: F = 0.885, P = 0.538 DED: F = 0.774, P = 0.443 |

F = 3.465 P = 0.019 |

IOP, intra-ocular pressure; DED, dry eye disease.

Figure 2.

Seasonal change in SPK (superficial punctate keratitis) score for patients with and without DED. The non-glaucoma group showed small seasonal amplitudes in both the DED (open symbol) and non-DED (closed symbol) groups, with peaks in the fall and the lowest levels in summer (left panel). Glaucoma patients showed apparently large seasonal amplitudes in both groups, with the peak in summer for those with DED and in fall for those without DED (right panel). DED; dry eye disease.

Figure 3.

Seasonal change in BUT for patients with and without DED. There was no obvious seasonal amplitude observed in the non-glaucoma (left panel) or glaucoma group (right panel), with DED (open symbol) and without DED (closed symbol). BUT; tear break up time, DED; dry eye disease.

The regression analysis of 2,311 patients examined in both summer and winter identified seasonality (P < 0.0001) as the factor most strongly correlated with IOP, compared with presence of DED and glaucoma, corneal staining score, frequency of glaucoma eye drop instillation, and number of medications (Table 3). It is notable that severe SPK (high corneal staining score) tended to occur with low IOP (P = 0.050). Multiple regression analysis revealed that age and seasonality most affected IOP in summer and winter (Table 4).

Table 3.

Regression analysis of IOP and various parameters.

| Dependent valuables | IOP | SPK | BUT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | − 0.271 (< 0.0001*) | − 0.052 (0.011*) | 0.013 (0.513) |

| SexA | − 0.004 (0.846) | − 0.171 (< 0.0001*) | 0.255 (< 0.0001*) |

| SeasonalityB | 0.096 (< 0.0001*) | 0.034 (0.096) | 0.023 (0.244) |

| Glaucoma | 0.006 (0.787) | 0.115 (< 0.0001*) | − 0.050 (0.014*) |

| Frequency of instillation | − 0.010 (0.616) | 0.145 (< 0.0001*) | − 0.038 (0.064) |

| # of medication | 0.010 (0.615) | 0.149 (< 0.0001*) | − 0.053 (0.010*) |

| MD | 0.054 (0.244) | – | – |

| Cupping | 0.014 (0.691) | – | – |

| GCC | 0.056 (0.089) | – | – |

| DED | 0.001 (0.949) | 0.226 (< 0.0001*) | – |

| SPK | − 0.041 (0.050) | – | − 0.223 (< 0.0001*) |

| BUT | 0.020 (0.352) | − 0.231 (< 0.0001*) | – |

Data show β values, with P–values in parentheses. *P < 0.05, AMale = 1, female = 0, BSummer = 0, Winter = 1, all are adjusted for age and gender.

IOP, intra-ocular pressure; GCC, ganglion cell complex; MD, mean deviation; DED, dry eye disease; BUT, tear break-up time; SPK, superficial punctate keratitis.

Table 4.

Multiple regression analysis with IOP.

| Age (year) | − 0.262 (< 0.0001*) |

| SexA | − 0.008 (0.712) |

| SeasonalityB | 0.096 (< 0.0001*) |

| DED | 0.0001 (0.996) |

| Glaucoma | 0.003 (0.870) |

Data show β values, with P-values in parentheses. *P < 0.05, AMale = 1, female = 0, BSummer = 0, Winter = 1, all are adjusted for age and gender.

IOP, intra-ocular pressure; DED, dry eye disease.

Discussion

Our results are compatible with previous studies of a seasonal fluctuation in IOP21,22 wherein IOP was higher during the winter than the summer by 0.5 mmHg for non-glaucoma patients without DED and by 1.0 mmHg for glaucoma patients without DED. Glaucoma medications might not contribute to this fluctuation since they tend to instead reduce the magnitude of diurnal fluctuations23,24. The advantage of the present study lies in the data being obtained from individual cases in a sufficiently large population covering all age groups without overlapping for 2 years. The status of DED varies across seasons if repeatedly examined so that this study design seems to work well to adequately classify the participants into groups with and without DED. We accordingly examined each patient once to immediately correlate IOP with DED, and future studies should be carried out in a standard method with repeated examinations on the same patients to adequately analyze seasonal variation.

We speculate a potential mechanism of seasonal fluctuations in IOP driven by three factors. The first is an autonomous nervous system (ANS) as conventionally hypothesized25,26 accounting for high IOP in winter. The second is SPK induced by BAK27, and the third is corneal thinning. The ANS regulates many systemic functions including body temperature, heart rate, and ocular function in the form of pupil diameter, accommodation, and IOP28.

Primary open-angle glaucoma is characterized by a large diurnal IOP change compared to controls and is typically induced by ANS dysregulation25,26. Koga and Tanihara suggested that ANS and/or cathecholamic tone could influence the IOP via vascular tone in blood pressure29. Furthermore, the high prevalence of comorbidity with abnormal ANS in DED patients might amplify the seasonal fluctuation in IOP30.

The severity of SPK was marginally correlated with IOP being lowest in summer, suggesting that increased drug permeability might enhance the pressure reduction effect. Tight junctions in the superficial cells of corneal epithelium are damaged by BAK contained in glaucoma medications31, which causes the junctions to degrade. As a consequence, the normal barrier function of the cornea suffers32. After exposure to BAK, the conjunctival epithelium can also directly undergo apoptosis. The corneal permeability generally corresponds to the concentration of BAK33 and also depends on the property of other ingredients34. However, the direct correlation between corneal permeability and actual pressure reduction effect has not been determined and some experimental results are contradictory with respect to SPK facilitating the intra-ocular penetration of anti-glaucoma solutions35. Thirdly, apparently low IOP in summer might be caused by corneal thinning36. The central corneal thickness decreases in DED37 and contributes to low IOP in summer, since measured IOP might be lower than the actual value. Ophthalmologists should be also aware that perimetric results could thus be overestimated in summer38 because the sensitivities in summer were 0.2 dB below those of winter/spring.

The limitations of our study include the regional and systemic background of participants, because both DED and IOP are closely associated with climate, temperature, humidity, ambient light, and various systemic parameters that should have been fully evaluated and adjusted for analysis. IOP shows normal diurnal variation and should therefore also be measured at a fixed schedule. We used a cross-sectional design, whereby each eye was tested only once, limiting the statistical power. A more powerful study design would involve measuring IOP in the same cohorts of glaucoma and non-glaucoma patients multiple times across the four seasons, so that the actual seasonal variation can be quantified and compared between groups. Our present study partially addressed such a limitation by including a large sample size. Diagnosis of glaucoma mostly depended on the clinical decision of each participating ophthalmologist rather than following strict diagnostic criteria, although classification of DED was clearly based on appropriate criteria and we were able to achieve reasonable results. Lastly, participants with ocular hypertension without medication would have better served as controls.

In conclusion, the seasonal variation was significant in most of study groups and IOP could tend to be low in summer. Possible explanations include ANS dysfunction, corneal thinning, and corneal change caused by DED and anti-glaucoma medication. We recommend noting to patients that IOP might be lowest in summer and highest in winter especially in patients with DED. We examined each patient once to correlate IOP with a timely onset of DED; however, standard practice also demands repeated examinations using the same patients to properly analyze seasonal variation.

Methods

Study participants and Institutional Review Board approval

We conducted a cross-sectional, case-control study in Komoro Kosei General Hospital (Nagano, Japan), Shinseikai Toyama Hospital (Toyama, Japan), Tsukuba Central Hospital (Ibaraki, Japan), Jiyugaoka Ekimae Eye Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), Todoroki Eye Clinic (Tokyo, Japan), and Takahashi-Hisashi Eye Clinic (Akita, Japan). We consecutively recruited participants visiting these eye clinics from March 2015 to February 2017. Exclusion criteria were visual impairment (< 20/25 in either eye), any ocular surgery within the last three months, or age under 20 years.

The latitude in the Tokyo area on mainland Japan is 35.68° North and day length varies by 4–6 h over the year according to averages for 1981–2010 reported by the Japan Meteorological Agency. Japan is characterized by four distinct seasons with marked variations in temperature, humidity, and daylight time. Generally, Japan is hot and humid in summer and cold and dry in winter. The Japan Meteorological Agency reported average temperatures and humidity from 5.2 °C and 52% in winter to 25.0 °C and 77% in summer in the Tokyo area in the years 1981–2010.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Keio University School of Medicine, Komoro Kosei General Hospital, Tsukuba Central Hospital, and Jiyugaoka Ekimae Eye Clinic and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Ophthalmological examinations

All cases were diagnosed as bilateral open-angle glaucoma or normal-tension glaucoma under slit lamp biomicroscopy. Glaucoma were diagnosed through routine examinations and a visual field test (Humphrey Visual Field Analyzer 30-2 standard program; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), measuring the thickness of ganglion cell complexes using optical coherent tomography (OCT; RC3000R) (Nidek, Gamagori, Japan and Cirrus® HD-OCT (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany)). Diagnostic criteria for glaucoma comprised glaucomatous visual field loss in the Glaucoma Hemifield Test, an ophthalmoscopic neurofiber layer defect, a cup/disc ratio > 0.6, or elevated IOP (> 21 mmHg) requiring topical medication for more than six months. Patients were excluded if they had retinal pathology, retinal surgery, photocoagulation affecting the visual field or coexisting cataract with significant lens opacity disturbing the optical axis that accounted for subjective visual disturbance or decreased visual function. Topical glaucoma medication included Xalatan® (Pfizer, Tokyo, Japan), Tapros® (Santen Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan), Travatanz® (Alcon Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan), Lumigan® (Senjyu Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan). Xalacom® (Pfizer), Tapcom® (Santen Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd), Duotrav® (Alcon Laboratories), Aifagan (Senjyu Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.), Detantol® (Santen Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.), Nipradinol® (Kowa), Mikelan® LA (Otsuka), and 0.5% Timoptol® XE (MSD).

DED was diagnosed according to the criteria of the Asia Dry Eye Society39: presence of DED-related symptom(s) and a tear break-up time (BUT) shorter or equal to 5 s. We also conducted the Schirmer test40, and measured maximum blinking interval (≤ 9 s) and superficial punctate keratoepitheliopathy (staining score ≥ 3).

Ophthalmological examinations

BUT was measured using a wetted fluorescein filter paper (Ayumi Pharmaceutical Co Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) applied at the lower lid margin. To ensure adequate mixing of the fluorescein dye with the tear film, subjects were instructed to blink three times. The interval between the third blink and appearance of the first dark spot in the cornea was measured three consecutive times using a stopwatch. For this study, we considered the means of the three measurements as the BUT. We scored the ocular surface in three sections (nasal conjunctiva, cornea, and temporal conjunctiva) on a scale of 0–3 for severity. Overall epithelial damage was graded on a scale of 0–941.

Statistical analysis

Participants were assigned to one of four groups based on the presence of glaucoma and/or DED. The season on the date of each patient’s visit was classified as follows: spring from March to May, summer from June to August, fall from September to November, and winter from December to February. The effect of season on IOP was assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the interaction was assessed using a two-way ANOVA. Regression analysis was performed to explore which parameters most affect seasonal difference in IOP. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as percentages where appropriate. All analyses were performed using StatFlexR (Atech, Osaka, Japan), with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Inter-Biotech (https://www.inter-biotech.com) with the English language editing of this manuscript.

Author contributions

M.K. collected and analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. M.K. and M.A. designed the study. M.K., M.A., K.Y., K.N., M.K., M.U. and K.T. reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Manami Kuze and Masahiko Ayaki.

Contributor Information

Manami Kuze, Email: manakuze@yahoo.co.jp.

Masahiko Ayaki, Email: mayaki@olive.ocn.ne.jp.

Kazuno Negishi, Email: kazunonegishi@keio.jp.

References

- 1.Rosnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bull. World Health Organ. 2004;82:844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leske MC, et al. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: the early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch. Ophthalmol. (Chicago, Ill:1960) 2003;12:48–56. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kass MA, et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. (Chicago, Ill: 1960) 2002;120:701–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buguet A, Py P, Romanet JP. 24-Hour (nyctohemeral) and sleep-related variations of intraocular pressure in healthy white individuals. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1994;117:342–347. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu JH, et al. Nocturnal elevation of intraocular pressure in young adults. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:2707–2712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee TE, Yoo C, Kim YY. Effects of different sleeping postures on intraocular pressure and ocular perfusion pressure in healthy young subjects. Ophthalmology. 2013;120:1565–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitazawa Y, Horie T. Diurnal variation of intraocular pressure in primary open-angle glaucoma. JAMA Ophthalmol. 1975;79:557–566. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(75)90792-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumenthal M, Blumenthal R, Peritz E, Best M. Seasonal variation in intraocular pressure. JAMA Ophthalmol. 1970;69:608–610. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(70)91628-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brody S, Erb C, Veit R, Rau H. Intraocular pressure changes: the influence of psychological stress and the Valsalva maneuver. Biol. Psychol. 1999;51:43–57. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0511(99)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohta H, Uji Y, Hattori Y, Sugimoto M, Higuchi K. Seasonal variation of intraocular pressure after trabeculotomy. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;96:1148–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henmi T, Yamabayashi S, Furuta H, Hosoda M, Fujimori K. Seasonal variation in intraocular pressure. Nippon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi. 1994;98:782–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asrani S, et al. Large diurnal fluctuations in intraocular pressure are an independent risk factor in patients with glaucoma. J. Glaucoma. 2000;9:134–142. doi: 10.1097/00061198-200004000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guenoun JM, et al. In vitro study of inflammatory potential and toxicity profile of latanoprost, travoprost, and bimatoprost in conjunctiva-derived epithelial cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:2444–2450. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cha SH, et al. Corneal epithelial cellular dysfunction from benzalkonium chloride (BAC) in vitro. Clin Exp. Ophthalmol. 2004;32:180–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2004.00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisella PJ, et al. Conjunctival proinflammatory and proapoptotic effects of latanoprost and preserved and unpreserved timolol: an ex vivo and in vitro study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004;45:1360–1368. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kass MA, et al. The ocular hypertension treatment study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hikichi T, et al. Prevalence of dry eye in Japanese eye centers. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1995;233:555–558. doi: 10.1007/BF00404705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baudouin C, et al. Preservatives in eyedrops: the good, the bad and the ugly. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2010;29:312–334. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li C, et al. Research on the stability of a rabbit dry eye model induced by topical application of the preservative benzalkonium chloride. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:1–9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan BD, et al. Correlations between commonly used objective signs and symptoms for the diagnosis of dry eye disease: clinical implications. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92:161–166. doi: 10.1111/aos.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qureshi IA, et al. Seasonal and diurnal variations of ocular pressure in ocular hypertensive subjects in Pakistan. Singap. Med. J. 1999;40:345–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng J, et al. Seasonal changes of 24-hour intraocular pressure rhythm in healthy Shanghai population. Medicine. 2016;95:e4453. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larsson LI, et al. The effect of latanoprost on circadian intraocular pressure. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2002;47:S90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00296-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orzalesi N, et al. Effect of timolol, latanoprost, and dorzolamide on circadian IOP in glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000;41:2566–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark CV, Mapstone R. Autonomic neuropathy in ocular hypertension. Lancet. 1985;2:185–187. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91500-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mapstone R, Clark CV. The prevalence of autonomic neuropathy in glaucoma. Trans. Ophthalmol. Soc. UK. 1985;104:265–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasmussen CA, Kaufman PL, Kiland JA. Benzalkonium chloride and glaucoma. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;30:163–169. doi: 10.1089/jop.2013.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergmanson JP. Neural control of Intraocular pressure. Am. J. Optom. 1982;59:94–98. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198201000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koga T, Tanihara H. Seasonal variant of intraocular pressure in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Jpn. J. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2001;55:1519–1522. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lambiase A, et al. Alterations of tear neuromediators in dry eye disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:981–986. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uematsu M, et al. Acute corneal epithelial change after instillation of BAC evaluated using a newly developed in vivo cornea. Ophthalmic Res. 2007;39:308–314. doi: 10.1159/000109986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson G, Ren H, Laurent J. Corneal epithelial fluorescein staining. J. Am. Optom. 1995;66:435–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda M, et al. Cytotoxic effect of generic versions of latanoprost ophthalmic solution on corneal epithelial cells and ocular pharmacokinetics of ophthalmic solutions in rabbits. Igaku Yakugaku. 2012;68:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baudouin C, et al. Flow cytometry in impression cytology specimens: a new method for evaluation of conjunctival inflammation. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1997;38:1458–1464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burstein NL. Preservative alteration of corneal permeability in humans and rabbits. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1984;25:1453–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brandt JD, et al. Ocular hypertension treatment study (OHTS) group. Central corneal thickness and measured IOP response to topical ocular hypotensive medication in the Ocular Hypertension Treatment study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2004;138:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ali NM, Hamied FM, Farhood QK. Corneal thickness in dry eyes in an Iraqi population. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017;11:435–440. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S119343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montolio FG, Wesselink C, Gordijn M, Jansonius NM. Factors that influence standard automated perimetry test results in glaucoma: test reliability, technician experience, time of day and season. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2012;53:7010–7017. doi: 10.1167/iovs.12-10268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsubota K, et al. Asia dry eye society. New perspectives on dry eye definition and diagnosis: a consensus report by the Asia dry eye society. Ocul. Surf. 2017;15:65–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schirmer O. Studien zur physiologie und pathologie der tranenabsonderung und tranenabfuhr. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 1903;56:197–291. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uchino M, et al. Prevalence of dry eye disease and its risk factors in visual display terminal users: the Osaka study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013;156:759–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]