Key Points

Question

What factors are associated with burnout/stress in trainee physicians?

Findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 48 studies included 36 266 trainee physicians. The odds ratios for the associations between workplace factors and burnout/stress were found to be higher compared with nonmodifiable and non–work-related factors such as age and grade.

Meaning

The findings of this study highlight the importance of improving training and work environments to possibly prevent burnout among trainee physicians and suggest that implementing multicomponent interventions to target major stressors uncovered in this study could be promising.

Abstract

Importance

Evidence suggests that physicians experience high levels of burnout and stress and that trainee physicians are a particularly high-risk group. Multiple workplace- and non–workplace-related factors have been identified in trainee physicians, but it is unclear which factors are most important in association with burnout and stress. Better understanding of the most critical factors could help inform the development of targeted interventions to reduce burnout and stress.

Objective

To estimate the association between different stressors and burnout/stress among physicians engaged in standard postgraduate training (ie, trainee physicians).

Data Sources

Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews from inception until April 30, 2019. Search terms included trainee, foundation year, registrar, resident, and intern.

Study Selection

Studies that reported associations between stressors and burnout/stress in trainee physicians.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two independent reviewers extracted the data and assessed the quality of the evidence. The main meta-analysis was followed by sensitivity analyses. All analyses were performed using random-effects models, and heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic.

Main Outcome and Measures

The main outcome was the association between burnout/stress and workplace- or non–workplace-related factors reported as odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% CIs.

Results

Forty-eight studies were included in the meta-analysis (n = 36 266, median age, 29 years [range, 24.6-35.7 years]). One study did not specify participants’ sex; of the total population, 18 781 participants (52%) were men. In particular, work demands of a trainee physician were associated with a nearly 3-fold increased odds for burnout/stress (OR, 2.84; 95% CI, 2.26-3.59), followed by concerns about patient care (OR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.58-3.50), poor work environment (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.57-2.70), and poor work-life balance (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.53-2.44). Perceived/reported poor mental or physical health (OR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.76-3.31), female sex (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.20-1.50), financial worries (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.07-1.72), and low self-efficacy (OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.31-3.46) were associated with increased odds for burnout/stress, whereas younger age and a more junior grade were not significantly associated.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this study suggest that the odds ratios for burnout and stress in trainee physicians are higher than those for work-related factors compared with nonmodifiable and non–work-related factors, such as age and grade. These findings support the need for organizational interventions to mitigate burnout in trainee physicians.

This systematic review and meta-analysis examines the factors associated with burnout and stress among physicians receiving standard postgraduate training.

Introduction

Trainee physicians are qualified physicians engaged in postgraduate training.1 There is evidence suggesting that physicians experience high levels of burnout and stress, and trainee physicians are a particularly high-risk group.2,3,4,5 Stress is a state of mental strain resulting from demanding circumstances.6 Burnout consists of 3 components: emotional exhaustion, reduced sense of personal accomplishment, and depersonalization.7,8 High burnout and stress levels have been found in trainee physicians working in the US, Australia, and Canada.9,10,11,12,13 Surveys on trainee physicians suggest that 50% were experiencing burnout symptoms and 80% were experiencing high stress.14 Burnout in trainee physicians can have profound effects on personal well-being, career prospects, and relationships and may jeopardize patient care.14 The well-being of trainee physicians is a benchmark for the sustainability of health care systems.15,16 Better understanding of factors that underpin feelings of stress and burnout in trainee physicians has important implications.

Workplace-related factors, such as workload and work-life conflict, and non–work-related factors have been found to be associated with burnout.13,16,17 However, owing to variations in methods and presentation of results, it is difficult to compare the findings between published studies and explore reasons for inconsistent results. Thus, we have conducted the first systematic review and meta-analysis to identify workplace- and non–workplace-related factors that are associated with burnout/stress in trainee physicians and the relative importance of these factors.

Methods

This review is reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines. MOOSE guidelines were also adopted because PRISMA mainly focuses on intervention studies whereas MOOSE guidelines focus on observational studies.18,19

Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic reviews were searched from inception until April 30, 2019. The search strategy included combinations of 3 key blocks of terms (stress, trainee physicians, and determinants of stress) using a combination of Medical Subject Headings and text words (eTable 1 in the Supplement). We used a wide range of terms for trainee physicians in our search, including trainee, foundation year, registrar, resident, and intern.

Database searches were supplemented by manual searches of reference lists of included articles. No previous systematic reviews were identified in the literature or within PROSPERO. eMethods in the Supplement provides the systematic review protocol.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met the following criteria. Regarding population, qualified physicians who were engaged in standard postgraduate training (ie, trainee physicians) were included. Studies that were based on a mix of trainee physicians and other physicians or health professionals were included if trainee physicians composed at least 70% of the sample.

Workplace-related factors (eg, work demands), non–workplace-related factors (eg, poor health), and demographic characteristics that may be associated with burnout and stress (eg, sex) were analyzed. In particular, studies had to explicitly state that they examined factors associated with burnout/stress (a wide range of terms was used, including determinants, drivers, contributors, drivers, causes, predictor, risk, or associate) in titles, abstracts, or key words (eMethods in the Supplement), and the main outcomes of the study were required to be burnout and stress. Studies using quantitative research designs, such as observational (eg, cohort, cross-sectional, and case-control), were included in the meta-analysis. Studies that took place in any health care setting, including primary and hospital care, were considered eligible.

Studies were excluded if they had not explicitly focused on burnout or stress, such as those exploring the determinants of specific psychiatric condition criteria (eg, depression and generalized anxiety disorder) or did not report investigation of factors associated with burnout or stress. Other exclusion criteria were studies reported as gray literature (research published outside the traditional academic literature), conference abstracts, letters to the editor, and non–peer-reviewed investigations, as well as those not published in the English language. In addition, studies that did not provide data amenable to meta-analysis were excluded.

Data Selection

Searches were exported into EndNote (Clarivate Analytics), and duplicate studies were removed. Study selection involved 2 stages. First, titles and abstracts of the identified studies were screened; subsequently, the full texts of relevant studies were accessed and further screened against the eligibility criteria. The title and abstract screening was undertaken by 1 of us (A.Y.Z.), and full text screening was performed by 2 of us (A.Y.Z. and M.P.). Interrater reliability was high (κ = 0.84). Disagreements were resolved through discussions.

If necessary, we contacted authors of relevant articles to request full texts or additional data. An Excel-based extraction form was piloted on 5 randomly selected studies. Data on the following factors were extracted: (1) country, method of recruitment, health care setting, research design, control, and location of the study; (2) sample size, age, sex, specialty, and trainee physician grade of the population; and (3) factors associated with burnout/stress (burnout, stress, and other), types of analysis used, and type of factors identified as outcomes.

We used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to critically appraise the quality of the studies. This scale was designed to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies (eg, case-control),20 but has been adapted for undertaking critical appraisals of cross-sectional studies.21 This modified NOS instrument provides scores from 0 to 10, with studies scoring greater than or equal to 6 classified as high quality. Two of us (A.Y.Z. and M.P.) assessed 20% of the studies, and interrater reliability was high (κ = 0.93). Subsequent articles were assessed by 1 of us (A.Y.Z.).

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome of this review was the association of identified factors with burnout/stress in trainee physicians. We calculated odds ratios (ORs) together with 95% CIs using Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (Biostat).22 Pooled ORs and forest plots were computed using the metaan command in Stata, version 14 (StataCorp).23 We chose to use ORs to pool the results because this measure was most commonly applied in individual studies and because ORs are considered more appropriate for cross-sectional studies.24 In accordance with recommendations,22 across studies reporting multiple measures of the same stressor category (eg, different measures of job demands, such as time on call or long working hours), the median ORs were computed to ensure that each study contributed only 1 estimate to each analysis. The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between studies. An I2 value of 0% to 49% indicated low heterogeneity; 50% to 74%, moderate; and 75% to 100%, high.25

Three sensitivity analyses were performed to examine whether the results were robust by (1) only including highly rated methodologic studies in the analyses (NOS score ≥6), (2) only including studies using measures of burnout, and (3) only including studies using the Maslach Burnout Inventory,7 which is typically viewed as a measure of prolonged stress.

Potential for publication bias was assessed on all pooled outcomes that included 9 or more studies26 by inspecting the symmetry of funnel plots and using the Egger test.27 Funnel plots were constructed using the metafunnel command and the Egger test was computed using the metabias command.28,29 All analyses were performed in Stata, version 14. A 2-tailed P value <.05 was the level of significance.

Results

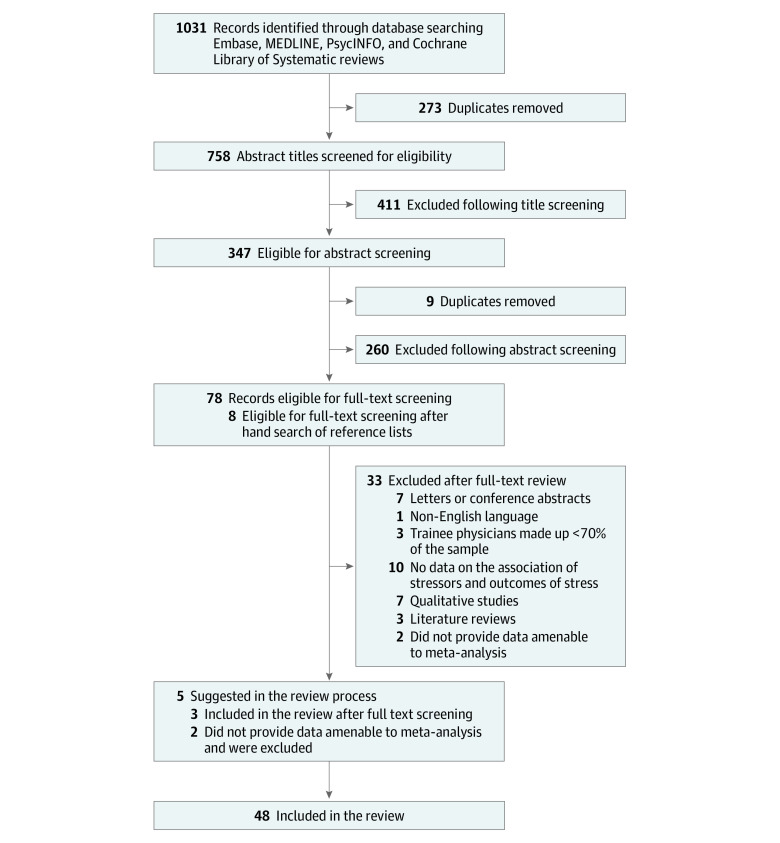

Overall, 1036 records were screened for eligibility. Following full-text screening, 48 studies met the eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Table 1 reports the included studies regarding population size, trainee grade, median age, study setting, location, types of measures used, response rates, and adapted NOS score. Across the 48 studies, a pooled cohort of 36 266 participants was formed.4,10,11,12,13,17,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 The median number of recruited trainee physicians was 203 (range, 58-16 394). One study43 did not specify participants’ sex; of the total cohort, 18 781 participants (52%) were men and 17 315 participants (48%) were women; median age was 29 years (range, 24.6-35.7). Thirty-seven studies11,13,30,31,32,33,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,53,54,57,58,59,61,62,63,64,65,67,68,69,70,71 (77%) used validated measures of burnout/stress. The Maslach Burnout Inventory was the most common measure of burnout (42%). The median response rate for cross-sectional studies was 61% (range, 15%-90%). Twenty-four studies31,33,34,35,37,41,42,43,46,47,48,49,52,53,57,58,60,61,64,65,66,67,68,70 (50%) had an adapted NOS score greater than or equal to 6 (range, 2-8). Eleven factors were identified in this review (Table 2).

Figure 1. Flowchart of Studies Included in the Review.

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies, Populations, and Outcomes Included in the Review.

| Study | Country | Health care setting | Research design | Sample size | Men, % | Mean age, y | Specialties | Working experience | Measure of wellnessa | Categories of stressors identified | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdulghani et al,11 2015 | Saudi Arabia | Hospital and primary care | Cross-sectional | 318 | 60 | 27.9 | Multiple | Residency year 1-4 | 2, Kessler-10 psychological distress instrument | Specialty grade, demographics, poor work-life balance, work demands | 4 |

| Abdulghani et al,30 2014 | Saudi Arabia | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 404 | 63 | Not stated | Multiple | Internship | 2, Kessler-10 psychological distress instrument | Demographics, specialty | 4 |

| Afzal et al,31 2010 | US | Hospital and primary care | Cross-sectional | 134 | 58 | Not stated | Multiple | Residency | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Specialty, demographics, poor work-life balance | 7 |

| Al-Ma'mari et al,32 2016 | Canada | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 47 | 13 | Not stated | Obstetrics and gynecology | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Poor work environment | 5 |

| Antoniou et al,33 2003 | Greece | Public hospital, clinics | Cross-sectional | 355 | 54 | Age range, 25-42 | Not specified | All training grades | 2, Occupational Stress Index | Poor career development, poor work-life balance, poor work environment, personal and self-efficacy, concerns about patient care, work demands, financial worries | 6 |

| Baer et al,34 2017 | US | Public hospital | Cross-sectional | 258 | 21 | 29 | Pediatrics | Residents | 1, 2-item burnout measure validated again Maslach Burnout Inventory | Demographics, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health poor work-life balance, work demands, seniority and grade, poor work environment | 7 |

| Baldwin et al,35 1997 | UK | Hospital | Prospective cohort | 142 | 55 | 25 | Not specified | Senior house officers | 2, General Health Questionnaire | Work demands, concerns about patient care | 6 |

| Bellolio et al,36 2014 | US | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 191 | 53 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 1, 2, Professional Quality of Life Scale which includes measures on burnout | Demographics, specialty, personal and self-efficacy, work demands | 2 |

| Blanchard et al,37 2010 | France | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 204 | 60 | Median, 28 | Oncology and hematology | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Work demands, poor career development, concerns about patient care | 8 |

| Byrne et al,38 2016 | Ireland | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 270 | 39 | Not stated | Multiple | Internship | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Poor career development, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health, poor work-life balance | 5 |

| Cohen and Patten,10 2005 | Canada | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 415 | 47 | 29 | Multiple | Residents | 2, Sources and amount of perceived stress | Poor work-life balance, financial worries, work demands, poor work environment, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | 4 |

| Cooke et al,39 2013 | Australia | Primary care | Cross-sectional | 128 | 33 | >20 | General practice | Registrar level | 1,3, Single-item scale for burnout validated against Maslach Burnout Inventory, professional quality-of-life scale | Concerns about patient care, seniority and grade, poor work environment, demographics, work demands, personal and self-efficacy, poor work-life balance, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | 5 |

| Creed et al,40 2014 | Australia | Hospital and primary care | Cross-sectional | 355 | 32 | 28 | Multiple | <4 y of graduation | 1,2, Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, 4-item academic stress scale | Work demands, financial worries, poor career development | 5 |

| Dyrbye et al,41 2018 | US | Hospital and primary care | Cross-sectional | 3588 | 49 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Specialty, demographics, poor work-life balance, financial worries | 8 |

| Esan et al,42 2014 | Nigeria | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 128 | 73 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Demographics, financial worries, poor work environment, poor career development, work demands | 6 |

| Firth-Cozens,43 1992 | UK | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 170 | Not stated | Not stated | Multiple | Postgraduate year 1 | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Personal and self-efficacy, demographics, poor work environment, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | 6 |

| Firth-Cozens,44 1990 | UK | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 70 | 0 | Not stated | Multiple | Postgraduate year 1 | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Poor work environment, concerns about patient care, poor work-life balance, work demands, poor career development, financial worries | 4 |

| Firth Cozens and Morrison,45 1989 | UK | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 173 | 57 | 24.6 | Multiple | Postgraduate year 1 | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Concerns about patient care, poor work environment, work demands | 4 |

| Galam et al,46 2013 | France | Primary care | Cross-sectional | 169 | 53 | 25.4 | General practice | General practice trainees | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Demographics, work demands, poor work environment, poor work-life balance, poor career development | 6 |

| Galam et al,47 2017 | France | Primary care | Longitudinal | 173 | 31.3 | 26.4 | General practice | General practice trainees | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Personal and self-efficacy | 6 |

| Gouveia et al,48 2017 | Brazil | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 129 | 48 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Concerns about patient care, specialty | 6 |

| Guenette and Smith,49 2017 | US | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 94 | 63 | Not stated | Radiology | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Poor work-life balance, seniority, demographics | 7 |

| Hameed et al,50 2018 | Saudi Arabia | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 181 | 41 | 27.6 | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Seniority, demographics, specialty | 5 |

| Hannan et al,51 2018 | Ireland | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 101 | 44 | 28 | Multiple | Interns | 1,3, Maslach Burnout inventory and General Health Questionnaire | Poor work environment, poor career development, concerns about patient care, financial worries, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health, work demands | 4 |

| Haoka et al,13 2010 | Japan | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 348 | 67 | Men, 26.2; women, 25.6 | Multiple | Residents | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Perceived/reported poor mental or physical health, work demands, poor work-life balance, personal and self-efficacy | 5 |

| Jex et al,52 1991 | US | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 1785 | 70 | 30 | Multiple | Residents | 2, General and work-related psychological strain | Work demands, concerns about patient care, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | 7 |

| Kassam et al,53 2015 | Canada | University of Calgary trainees | Cross-sectional | 317 | 39 | 30.9 | Multiple | Residents | 1,3, Copenhagen Burnout Inventory and work satisfaction | Work demands, personal and self-efficacy, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | 7 |

| Kimo Takayesu et al,542014 | US | Residency program | Cross-sectional | 218 | 59 | Not stated | Emergency medicine | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Poor work environment, personal and self-efficacy | 5 |

| Kshatri et al,55 2017 | India | 3 Hospitals | Cross-sectional | 250 | 68 | 29 | Multiple | Residents | 2, Workplace Stress Scale | Seniority, demographics | 4 |

| Maraolo et al,17 2017 | Europe | Trainee association -microbiology | Cross-sectional | 416 | 38 | 32 | Microbiology | Residents | 1, Own burnout questionnaire | Demographics, poor work environment | 4 |

| Ndom and Makanjuola,56 2004 | Nigeria | Teaching hospital | Cross-sectional | 84 | 91 | 33 | Multiple | Residents | 2, List of stressors | Work demands, poor work environment, personal and self-efficacy, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health, demographics | 2 |

| Ochsmann et al57 2011 | Germany | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 792 | 44 | 28.9 | Multiple | All training grades | 3, Recovery Stress Questionnaire | Work demands, poor work environment | 7 |

| Ogundipe et al,58 2014 | Nigeria | Hospital setting | Cross-sectional | 204 | 58 | 33.4 | Multiple | Residents | 1,3, General Health Questionnaire and Maslach Burnout Inventory | Work demands, personal and self-efficacy, demographics, poor work environment | 7 |

| Ogunsemi et al,12 2010 | Nigeria | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 58 | 74 | 35.7 | Multiple | Residents | 2,3, Measured perception and sources of stress and perception of well-being | 3 | |

| Demographics, poor career development, personal and self-efficacy, poor work environment, concerns about patient care, work demands, financial worries, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | |||||||||||

| Okpozo et al,59 2017 | US | 3 Teaching hospitals | Cross-sectional | 203 | 52 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Personal and self-efficacy, poor work environment | 4 |

| Pan et al,60 2017 | Australia | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 540 | 40 | Not stated | Multiple | Postgraduate Year 1-3 | 2, Perception of stress | Work demands, poor career development, personal and self-efficacy, poor work environment, concerns about patient care | 8 |

| Prins et al,61 2010 | Holland | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 2115 | 39 | 31.5 | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Demographics, poor work-life balance, specialty | 8 |

| Saini et al,62 2010 | India | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 721 | 53 | 27.5 | Multiple | Residents | 2,3, Depression Anxiety Stress Scale | Seniority, specialty, work demands, poor career development, personal and self-efficacy | 5 |

| Sochos et al,63 2012 | UK | Hospital and primary care | Cross-sectional | 184 | 40 | 30.6 | Multiple | All training grades | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Personal and self-efficacy, poor work environment, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health | 4 |

| Stucky et al,4 2009 | US | Hospital | Prospective study | 144 | 36 | Interns, 27.9; residents, 29.4 | Pediatric and internal medicine | Interns and residents | 3, Measuring emotional state every 90 min throughout each duty shift | Seniority, demographics, work demands, poor health | 5 |

| Taylor-East et al,64 2013 | Malta | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 117 | 53 | Not stated | Multiple | Foundation years 1 and 2 | 3, General Health Questionnaire | Seniority, demographics, personal and self-efficacy, poor career development | 7 |

| Toral-Villanueva et al,65 2009 | Mexico | Hospital | Cross-sectional survey | 312 | 57 | 28 | Multiple | All training grades | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Concerns about patient care, perceived/reported poor mental or physical health, work demands, seniority | 8 |

| Tyssen et al,662005 | Norway | Hospital | Longitudinal | 371 | 58 | 29 | Multiple | Interns | 2, Modified version of Cooper Job Stress Questionnaire | Demographics, personal and self-efficacy, work demands, poor work environment | 7 |

| Verweij et al,67 2017 | Holland | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 2115 | 39 | 31.5 | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Work demands, personal and self-efficacy, demographics, poor career development | 8 |

| West et al,68 2011 | US | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 16394 | 55.7 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Demographics, financial worries, seniority | 8 |

| Woodside et al,69 2008 | US | Hospital and primary care | Cross-sectional | 155 | 57 | 35 | Family medicine and psychiatry | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Demographics, poor work-life balance, specialty | 4 |

| Zis et al,702015 | Greece | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 116 | 45 | 34.5 | Neurology | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Demographics, work demands, poor work-life balance, poor career development | 7 |

| Zubairi and Noordin,71 2016 | Pakistan | Hospital | Cross-sectional | 110 | 54 | Not stated | Multiple | Residents | 1, Maslach Burnout Inventory | Work demands, poor work environment | 4 |

Code for measure of wellness: 1, burnout (eg, Maslach Burnout Inventory); 2, stress (eg, Kessler-10 psychological distress instrument); and 3, other measures (eg, General Health Questionnaire).

Table 2. Factors Associated With Stress or Burnout Identified in This Review and Meta-analysis.

| Factors associated with burnout/stress | Description of outcomes | No. of studies |

|---|---|---|

| Work-related | ||

| Poor work-life balance | Balance and potential interference between personal and professional life, including leisure time, family responsibilities, and influence of work on personal life | 23 |

| Concerns about patient care | Concerns around mistakes, poor patient outcomes, and suboptimal practices | 9 |

| Work demands | The work duties of trainee physicians, including workload, inefficient tasks, responsibility, job satisfaction, and on-call commitments | 25 |

| Seniority and grade | Level of training | 11 |

| Poor career development | Training opportunities, professional development, and job security | 13 |

| Specialties | Obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, medicine, surgery, psychiatry, and emergency | 10 |

| Poor work environment | Relationships at work, supervision and support, lack of feedback, negative work environment, size of residency program, and organizational constraints | 19 |

| Non-work related | ||

| Financial worries | Perceived poor salary and financial problems and debt | 8 |

| Demographics | Sex, age, cultural background (eg, English as first language, migration, ethnicity, parental relationships) | 16 |

| 10 | ||

| 7 | ||

| Perceived/reported mental or physical poor health | Medical history, including mental health, nutrition, sleep, and lifestyle factors | 8 |

| Personal and self-efficacy | Control, autonomy, confidence, and self-efficacy | 11 |

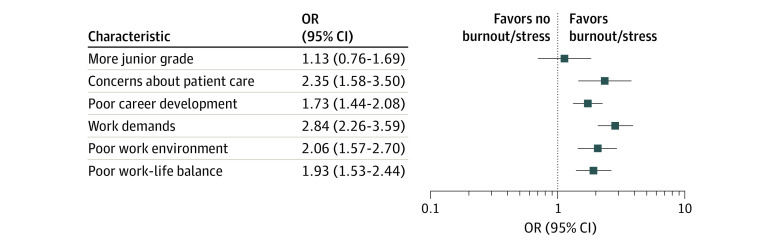

As shown in Figure 2, workplace-related demands were associated with nearly 3-fold increased odds for burnout/stress (OR, 2.84; 95% CI, 2.26-3.59; I2 = 88.8%; P < .001), followed by concerns about patient care (OR, 2.35; 95% CI, 1.58-3.50; I2 = 83.2%; P < .001), poor work environment (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.57-2.70; I2 = 82.8%; P < .010), poor work-life balance (OR, 1.93; 95% CI, 1.53-2.44; I2 = 85.7%; P < .001), and poor career development (OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.44-2.08; I2 = 71.4%; P < .001). Forest plots of individual workplace-related and non–workplace-related factors can be found in eFigure 1 in the Supplement.

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of Each Work-Related Factor and Its Association With Burnout/Stress.

Each line represents 1 factor. Weights are from random-effects model. OR indicates odds ratio.

There was no association between higher rates of burnout/stress and seniority within trainee physicians (OR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.76-1.69; I2 = 87.7%; P < .001). Studies were based on a range of different specialties, but there was no standard comparator specialty among the included studies; therefore, evaluating associations between burnout and specialties was challenging. The pooled estimate across 4 studies31,56,61,69 indicated that psychiatry was associated with a statistically significant higher level of burnout/stress (OR, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.1-1.8; I2 = 22.8%; P = .27) compared with family medicine and surgery (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

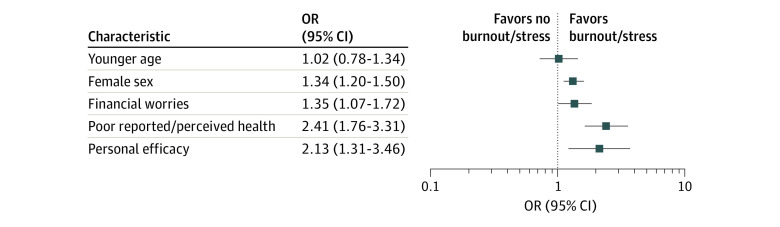

Findings on non–work-related factors showed an association with increased odds for burnout/stress for perceived/reported poor mental or physical health (OR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.76-3.31; I2 = 70.1%; P = .001), low personal and self-efficacy (OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.31-3.46; I2 = 93.6%; P < .001), financial worries (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 1.07-1.72; I2 = 62.7%; P = .009), and female sex (OR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.20-1.50; I2 = 41.7%; P = .05) (Figure 3). Younger age (OR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.78-1.34; I2 = 59.6%; P = .008) was not associated with burnout/stress. Owing to the heterogeneous data for culture and background, which included measures such as migration,64 spoken language,31 upbringing,43 ethnicity,34 and whether trainees were accustomed to US culture,69 it was not possible to pool data; thus, the ORs of each study are presented in a forest plot (eFigure 1B in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Meta-analysis of Each Non–Work-Related Factor and Its Association With Burnout/Stress.

Each line represents 1 factor. Weights are from random-effects model. OR indicates odds ratio.

Pooled ORs for most outcomes in the 3 sensitivity analyses (studies based only on burnout and Maslach Burnout Inventory measures; studies with ≥6 scorings on the adapted NOS) did not differ significantly from the pooled ORs reported in the main analyses (eTable 2 in the Supplement). However, no association was found with personal and self-efficacy when only burnout and Maslach Burnout Inventory measures were included.

The Egger test was undertaken for the pooled ORs of poor career development, female sex, more junior training level, concerns about patient care, work demands, poor work environment, and poor work-life balance. No evidence for publication bias was obtained for all pooled outcomes except work demands. The pooled OR between work demands and burnout/stress may be influenced by publication bias (regression intercept, 2.95; SE, 0.96; P = .006). Individual funnel plots can be found in eFigure 3 in the Supplement.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 48 studies across 36 266 trainee physicians examined a range of factors associated with burnout and stress. The reviewed evidence suggests that trainee physicians reporting negative workplace conditions, such as dysfunctional work environment, excessive work demands, and concerns about patient care, were 2 times more likely to report burnout/stress. We also found evidence that some non–work-related factors may be associated with burnout/stress in trainee physicians, but most of these appear to be less important than workplace factors and less robust based on our sensitivity analyses.

Two previous literature reviews have focused on burnout and explored the association between contributing factors and burnout in trainee physicians.16,72 These were not systematic reviews, but identified high work demands, poor work-life balance, poor control, and poor work environments as potential contributors.15,41

In our study, we undertook meta-analysis, enabling the quantifications and comparisons of these links and allowing for exploration of key sources of heterogeneity among the studies. We chose to focus on all trainee physicians engaged in postgraduate training to understand the factors associated with burnout/stress in trainee physicians as a group, as previous reviews have focused on residents. Including physicians only at residency grade may not take into account different nomenclature used in different countries, as well as other trainee physician grades (eg, interns).

Control and personality have been implicated in previous literature reviews,16,72 and our study found an association between personal and self-efficacy and burnout/stress in the overall analyses. However, this association was less robust after sensitivity analyses were performed. This weaker association could be due to differences in assessments, but these factors could also be affected by support and coping, which could moderate the association.72 Further high-quality studies are required to explore this factor in more detail.

Our results support the need for organizational interventions, which is in line with previous reviews.73 Most studies that evaluated interventions to reduce burnout have focused on physician-directed interventions, such as mindfulness and building self-confidence.73 Studies that have tested organizational interventions tend to focus mostly on modifying shift patterns and workload,73 but few studies have incorporated interventions that try to address multiple organizational factors, including improved teamwork, workflow, and organizational restructuring,73,74,75 which may be more useful in reducing burnout. Our findings suggest a need to shift to research agendas that target the organizational environment, improving working relationships among physicians and other health care professionals, as well as promoting work-life balance to mitigate burnout in trainee physicians. Although organizational interventions are generally considered costly and time-consuming, they may still be efficient and cost-effective owing to increased retention of physicians and improved quality of patient care.76,77

Among specialties, psychiatry was found to be associated with particularly high risk for burnout/stress. There might also be additional high-risk specialties that we could not detect owing to the high heterogeneity and lack of consistency in the comparator groups (surgery, internal medicine, family medicine, psychiatry, and emergency medicine) used across studies. Moreover, burnout is prevalent across all specialties, which makes it difficult to identify significant differences at the specialty level.5,14 Burnout symptoms have been found to differ among different specialties, which could indicate that there are some systematic differences in working conditions that are associated with burnout between different specialties.15 In obstetrics and gynecology, high litigation levels and workforce retention78 have been factors associated with burnout; however, only 3 studies in our review investigated this specialty. Regarding psychiatry, it has been suggested that over one-third of psychiatry trainees met the criteria for severe burnout, and reasons for leaving included job stress, unsuitability, and concerns about lack of evidence-based treatments.79,80

Female trainee physicians showed an association with burnout/stress that is consistent with previous research.15 This association could be due to higher work-life interference, especially among women with younger children.15,81 Moreover, there have been reports that workplace sexual harassment and sex-based discrimination can contribute to burnout.82 Based on our findings, further research is warranted to develop appropriate interventions to mitigate burnout/stress in these higher-risk groups (eg, women and psychiatry trainees).

We found that workplace-related factors, such as poor work environment, excessive work demands, and poor work-life balance, were statistically significantly associated with burnout/stress. Poor work-life balance has been found to affect physicians in general15 (ie, not just trainee physicians), but other contributing factors present during training, such as postgraduate training requirements conflicting with personal life, could further affect work-life balance. One aspect of work environment mentioned by Prins et al83 was support and satisfying work relationships. Lack of senior support and feedback have been associated with physician burnout, whereas residents with mutually beneficial supervision were found to have lower levels of burnout,84 which suggests that support may have a buffering effect on burnout.85 In addition to the supervisor and trainee physician relationship, coherent team structures may also protect against burnout.86 It is likely that workplace-related and non–workplace-related factors interact and dynamically influence each other, which in turn suggests the need for multicomponent interventions focusing on individuals as well as organizations.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis exploring factors associated with burnout/stress in trainee physicians. Undertaking meta-analysis enabled comparisons to be made between workplace- and non–workplace-related factors associated with burnout/stress and examination of the consistencies of the associations. In addition, this review was performed and reported according to the PRISMA and MOOSE guidelines.18,19

There are limitations to the study. A wide range of factors associated with burnout/stress were included in this review, some of which had to be pooled in the same category (eg, work demands). We accounted for large heterogeneity by applying random-effects models to adjust for study-level variations. Another possible solution could be to apply subgroup and meta-regression analyses, but such analyses are not advisable when the pooled associations are based on a relatively small number of studies (eg, <20/outcome). Furthermore, owing to the intrinsic limitation of the study design, it is not possible to identify a specific joint model to investigate combined contributions across factors. We suggest that future empirical studies be conducted to examine the joint contribution of the core factors that we found to be associated with burnout.

An eligibility criterion to ensure feasibility of this review was that studies explicitly stated that they examined factors associated with burnout/stress. Although we searched multiple bibliographic databases and screened the references of the eligible studies, studies that did not state that factors associated with burnout/stress (eg, in titles, abstracts, or key words) were investigated may have not been captured by our searches. We excluded gray literature because unpublished studies are generally of lower quality and are more difficult to combine than peer-reviewed articles.87 We also excluded non-English language articles, although our search did not identify any eligible studies excluded solely based on language.

It could be argued that meta-analysis is inappropriate in the context of high levels of method and statistical heterogeneity and it may have been more appropriate to summarize the results as a narrative review. However, meta-analysis enabled us to compare results across studies, examine the consistency of associations, and present the results in a way that facilitates interpretation compared with lengthy narratives.88 In addition, most of the studies included in our review were cross-sectional and hence we are not able to establish direct links between contributing factors and burnout/stress. Large, prospective investigations are needed to rigorously examine contributors to burnout/stress in trainee physicians over time.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that burnout/stress in trainee physicians is predominantly associated with workplace-related factors, such as work demands and poor work environment, rather than nonmodifiable and non–workplace-related factors. Multilevel organizational interventions targeting poor work environment and work demands have the potential to mitigate burnout and stress in trainee physicians.

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Comparison of Pooled Outcome Sizes of Main Analyses and Sensitivity Analyses

eFigure 1. Forest Plots of Association Between Burnout and Different Factors

eFigure 2. Meta-analysis of Each Individual Specialty and Its Association With Burnout/Stress

eFigure 3. Funnel Plots

eMethods. Systematic Review Protocol

eReferences

References

- 1.The British Medical Association Doctors' titles: explained. 2017. Accessed July 21, 2019. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/international-doctors/life-and-work-in-the-uk/toolkit-for-doctors-new-to-the-uk/doctors-titles-explained

- 2.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peisah C, Latif E, Wilhelm K, Williams B. Secrets to psychological success: why older doctors might have lower psychological distress and burnout than younger doctors. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13(2):300-307. doi: 10.1080/13607860802459831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stucky ER, Dresselhaus TR, Dollarhide A, et al. Intern to attending: assessing stress among physicians. Acad Med. 2009;84(2):251-257. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181938aad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among US medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general US population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeBlanc VR. The effects of acute stress on performance: implications for health professions education. Acad Med. 2009;84(10)(suppl):S25-S33. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b37b8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP, Schaufeli WB, Schwab RL. Maslach Burnout Inventory Consulting Psychologists Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol. 2001;52(1):397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markwell AL, Wainer Z. The health and wellbeing of junior doctors: insights from a national survey. Med J Aust. 2009;191(8):441-444. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen JS, Patten S. Well-being in residency training: a survey examining resident physician satisfaction both within and outside of residency training and mental health in Alberta. BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdulghani HM, Al-Harbi MM, Irshad M. Stress and its association with working efficiency of junior doctors during three postgraduate residency training programs. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:3023-3029. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S92408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogunsemi OO, Alebiosu OC, Shorunmu OT. A survey of perceived stress, intimidation, harassment and well-being of resident doctors in a Nigerian Teaching Hospital. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13(2):183-186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haoka T, Sasahara S, Tomotsune Y, Yoshino S, Maeno T, Matsuzaki I. The effect of stress-related factors on mental health status among resident doctors in Japan. Med Educ. 2010;44(8):826-834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03725.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Health Education England Junior doctor morale: Understanding best practice working environments. 2017. Accessed July 21, 2019. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Junior%20Doctors'%20Morale%20-%20understanding%20best%20practice%20working%20environments_0.pdf

- 15.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ, van der Heijden FM, van de Wiel HB, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Burnout in medical residents: a review. Med Educ. 2007;41(8):788-800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maraolo AE, Ong DSY, Cortez J, et al. ; Trainee Association of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) . Personal life and working conditions of trainees and young specialists in clinical microbiology and infectious diseases in Europe: a questionnaire survey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36(7):1287-1295. doi: 10.1007/s10096-017-2937-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008-2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2014. Accessed July 21, 2019. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 21.Hygum K, Starup-Linde J, Harsløf T, Vestergaard P, Langdahl BL. Mechanisms in endocrinology: diabetes mellitus, a state of low bone turnover—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2017;176(3):R137-R157. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kontopantelis E, Reeves D. metaan: Random-effects meta-analysis. Stata J. 2010;10(3):395. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1001000307 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG 9.2 Types of data and effect measures. 2011. In: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 5.1.0. Accessed July 21, 2019. https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_2_types_of_data_and_effect_measures.htm

- 25.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta-analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1119-1129. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00242-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterne JA, Harbord RM. Funnel plots in meta-analysis. Stata J. 2004;4:127-141. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0400400204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harbord RM, Harris RJ, Sterne JA. Updated tests for small-study effects in meta-analyses. Stata J. 2009;9(2):197. doi: 10.1177/1536867X0900900202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abdulghani HM, Irshad M, Al Zunitan MA, et al. Prevalence of stress in junior doctors during their internship training: a cross-sectional study of three Saudi medical colleges’ hospitals. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2014;10:1879-1886. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S68039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Afzal KI, Khan FM, Mulla Z, Akins R, Ledger E, Giordano FL. Primary language and cultural background as factors in resident burnout in medical specialties: a study in a bilingual US city. South Med J. 2010;103(7):607-615. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e20cad [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Ma’mari NO, Naimi AI, Tulandi T. Prevalence and predictors of burnout among obstetrics and gynecology residents in Canada. Gynecol Surg. 2016;13(4):323-327. doi: 10.1007/s10397-016-0955-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Antoniou A-SG, Davidson MJ, Cooper CL. Occupational stress, job satisfaction and health state in male and female junior hospital doctors in Greece. J Manag Psychol. 2003;18(6):592-621. doi: 10.1108/02683940310494403 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baer TE, Feraco AM, Tuysuzoglu Sagalowsky S, Williams D, Litman HJ, Vinci RJ. Pediatric resident burnout and attitudes toward patients. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20162163. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baldwin PJ, Dodd M, Wrate RW. Young doctors’ health—I: how do working conditions affect attitudes, health and performance? Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(1):35-40. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00306-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellolio MF, Cabrera D, Sadosty AT, et al. Compassion fatigue is similar in emergency medicine residents compared to other medical and surgical specialties. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(6):629-635. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.5.21624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanchard P, Truchot D, Albiges-Sauvin L, et al. Prevalence and causes of burnout amongst oncology residents: a comprehensive nationwide cross-sectional study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46(15):2708-2715. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrne D, Buttrey S, Carberry C, Lydon S, O’Connor P. Is there a risk profile for the vulnerable junior doctor? Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185(3):603-609. doi: 10.1007/s11845-015-1316-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooke GP, Doust JA, Steele MC. A survey of resilience, burnout, and tolerance of uncertainty in Australian general practice registrars. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:2. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Creed PA, Rogers ME, Praskova A, Searle J. Career calling as a personal resource moderator between environmental demands and burnout in Australian junior doctors. J Career Dev. 2014;41(6):547-561. doi: 10.1177/0894845313520493 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114-1130. Retracted in: JAMA. 2019;321(12):1220-1221. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.12615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Esan O, Adeoye A, Onakoya P, et al. Features of residency training and psychological distress among residents in a Nigerian teaching hospital. S Afr J Psychiatr. 2014;20(2):46. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v20i2.426 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Firth-Cozens J. The role of early family experiences in the perception of organizational stress: fusing clinical and organizational perspectives. J Occup Organ Psychol. 1992;65(1):61-75. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1992.tb00484.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Firth-Cozens J. Source of stress in women junior house officers. BMJ. 1990;301(6743):89-91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6743.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Firth-Cozens J, Morrison LA. Sources of Stress and Ways of Coping in Junior House Officers. Stress Med. 1989;5(2):121-126. doi: 10.1002/smi.2460050210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Galam E, Komly V, Le Tourneur A, Jund J. Burnout among French GPs in training: a cross-sectional study. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(608):e217-e224. doi: 10.3399/bjgp13X664270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galam E, Vauloup Soupault C, Bunge L, Buffel du Vaure C, Boujut E, Jaury P. ‘Intern life’: a longitudinal study of burnout, empathy, and coping strategies used by French GPs in training. BJGP Open. 2017;1(2):X100773. Published online June 14, 2017. doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen17X100773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gouveia PADC, Ribeiro MHC, Aschoff CAM, Gomes DP, Silva NAFD, Cavalcanti HAF. Factors associated with burnout syndrome in medical residents of a university hospital. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2017;63(6):504-511. doi: 10.1590/1806-9282.63.06.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guenette JP, Smith SE. Burnout: prevalence and associated factors among radiology residents in New England with comparison against United States resident physicians in other specialties. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;209(1):136-141. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hameed TK, Masuadi E, Al Asmary NA, Al-Anzi FG, Al Dubayee MS. A study of resident duty hours and burnout in a sample of Saudi residents. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):180. doi: 10.1186/s12909-018-1300-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hannan E, Breslin N, Doherty E, McGreal M, Moneley D, Offiah G. Burnout and stress amongst interns in Irish hospitals: contributing factors and potential solutions. Ir J Med Sci. 2018;187(2):301-307. doi: 10.1007/s11845-017-1688-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jex SM, Hughes P, Storr C, Baldwin DC Jr, Conard S, Sheehan DV. Behavioral consequences of job-related stress among resident physicians: the mediating role of psychological strain. Psychol Rep. 1991;69(1):339-349. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1991.69.1.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kassam A, Horton J, Shoimer I, Patten S. Predictors of well-being in resident physicians: a descriptive and psychometric study. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):70-74. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00022.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimo Takayesu J, Ramoska EA, Clark TR, et al. Factors associated with burnout during emergency medicine residency. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(9):1031-1035. doi: 10.1111/acem.12464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kshatri J, Das S, Kar P, Agarwal S, Tripathy R. Stress among clinical resident doctors of odisha: a multi-centric mixed methodology study. Indian J Public Health Res Dev. 2017;8(4):122. doi: 10.5958/0976-5506.2017.00325.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ndom RJ, Makanjuola AB. Perceived stress factors among resident doctors in a Nigerian teaching hospital. West Afr J Med. 2004;23(3):232-235. doi: 10.4314/wajm.v23i3.28128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ochsmann E, Lang J, Drexler H, Schmid K. Stress and recovery in junior doctors. Postgrad Med J. 2011;87(1031):579-584. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2010.103515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ogundipe OA, Olagunju AT, Lasebikan VO, Coker AO. Burnout among doctors in residency training in a tertiary hospital. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;10:27-32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okpozo AZ, Gong T, Ennis MC, Adenuga B. Investigating the impact of ethical leadership on aspects of burnout. Leadersh Organ Dev J. 2017;38(8):1128-1143. doi: 10.1108/LODJ-09-2016-0224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pan TY, Fan HS, Owen CA. The work environment of junior doctors: their perspectives and coping strategies. Postgrad Med J. 2017;93(1101):414-419. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2016-134362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. Burnout and engagement among resident doctors in the Netherlands: a national study. Med Educ. 2010;44(3):236-247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03590.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Saini NK, Agrawal S, Bhasin SK, Bhatia MS, Sharma AK. Prevalence of stress among resident doctors working in medical colleges of Delhi. Indian J Public Health. 2010;54(4):219-223. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.77266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sochos A, Bowers A, Kinman G. Work stressors, social support, and burnout in junior doctors: exploring direct and indirect pathways. J Employ Couns. 2012;49(2):62-73. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1920.2012.00007.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Taylor-East R, Grech A, Gatt C. The mental health of newly graduated doctors in Malta. Psychiatr Danub. 2013;25(suppl 2):S250-S255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toral-Villanueva R, Aguilar-Madrid G, Juárez-Pérez CA. Burnout and patient care in junior doctors in Mexico City. Occup Med (Lond). 2009;59(1):8-13. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tyssen R, Vaglum P, Grønvold NT, Ekeberg Ø. The relative importance of individual and organizational factors for the prevention of job stress during internship: a nationwide and prospective study. Med Teach. 2005;27(8):726-731. doi: 10.1080/01421590500314561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verweij H, van der Heijden FMMA, van Hooff MLM, et al. The contribution of work characteristics, home characteristics and gender to burnout in medical residents. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22(4):803-818. doi: 10.1007/s10459-016-9710-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.West CP, Shanafelt TD, Kolars JC. Quality of life, burnout, educational debt, and medical knowledge among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2011;306(9):952-960. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Woodside JR, Miller MN, Floyd MR, McGowen KR, Pfortmiller DT. Observations on burnout in family medicine and psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):13-19. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zis P, Artemiadis AK, Lykouri M, et al. Residency training: Determinants of burnout of neurology trainees in Attica, Greece. Neurology. 2015;85(11):e81-e84. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zubairi AJ, Noordin S. Factors associated with burnout among residents in a developing country. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2016;6:60-63. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.01.090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132-149. doi: 10.1111/medu.12927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Bower P, et al. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):195-205. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Shanafelt T. Physician-organization collaboration reduces physician burnout and promotes engagement: the Mayo Clinic experience. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61(2):105-127. doi: 10.1097/00115514-201603000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, et al. A cluster randomized trial of interventions to improve work conditions and clinician burnout in primary care: results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105-1111. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, et al. Association between physician burnout and patient safety, professionalism, and patient satisfaction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317-1330. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 77.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714-1721. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bourne T, Shah H, Falconieri N, et al. Burnout, well-being and defensive medical practice among obstetricians and gynaecologists in the UK: cross-sectional survey study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e030968. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lambert TW, Turner G, Fazel S, Goldacre MJ. Reasons why some UK medical graduates who initially choose psychiatry do not pursue it as a long-term career. Psychol Med. 2006;36(5):679-684. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705007038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jovanović N, Podlesek A, Volpe U, et al. Burnout syndrome among psychiatric trainees in 22 countries: Risk increased by long working hours, lack of supervision, and psychiatry not being first career choice. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;32:34-41. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Langballe EM, Innstrand ST, Aasland OG, Falkum E. The predictive value of individual factors, work-related factors, and work-home interaction on burnout in female and male physicians: a longitudinal study. Stress Health. 2011;27(1):73-87. doi: 10.1002/smi.1321 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives. Published May 2019. Accessed July 17, 2020. https://nam.edu/gender-based-differences-in-burnout-issues-faced-by-women-physicians/

- 83.Prins JT, Hoekstra-Weebers JE, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, et al. The role of social support in burnout among Dutch medical residents. Psychol Health Med. 2007;12(1):1-6. doi: 10.1080/13548500600782214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Dillingh GS, van de Wiel HB, van der Heijden FM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. The relationship between reciprocity and burnout in Dutch medical residents. Med Educ. 2008;42(7):721-728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03041.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dahlin M, Fjell J, Runeson B. Factors at medical school and work related to exhaustion among physicians in their first postgraduate year. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64(6):402-408. doi: 10.3109/08039481003759219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Willard-Grace R, Hessler D, Rogers E, Dubé K, Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Team structure and culture are associated with lower burnout in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):229-238. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McAuley L, Pham B, Tugwell P, Moher D. Does the inclusion of grey literature influence estimates of intervention effectiveness reported in meta-analyses? Lancet. 2000;356(9237):1228-1231. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02786-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Panagioti M, Stokes J, Esmail A, et al. Multimorbidity and patient safety incidents in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Search Strategy

eTable 2. Comparison of Pooled Outcome Sizes of Main Analyses and Sensitivity Analyses

eFigure 1. Forest Plots of Association Between Burnout and Different Factors

eFigure 2. Meta-analysis of Each Individual Specialty and Its Association With Burnout/Stress

eFigure 3. Funnel Plots

eMethods. Systematic Review Protocol

eReferences