Abstract

Background

The profiles of liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19 patients need to be clarified.

Methods

In this retrospective study, consecutive COVID‐19 patients over 60 years old in Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University from January 1 to February 6 were included. Data of demographics, clinical characteristics, comorbidities, laboratory tests, medications and outcomes were collected and analysed. Sequential alterations of serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were monitored.

Results

A total of 330 patients were included and classified into two groups with normal (n = 234) or elevated ALT (n = 96). There were fewer females (40.6% vs 54.7%, P = .020) and more critical cases (30.2% vs 19.2%, P = .026) in patients with elevated ALT compared with the normal group. Higher levels of bacterial infection indices (eg, white blood cell count, neutrophil count, C‐reactive protein and procalcitonin) were observed in the elevated group. Spearman correlation showed that both ALT and AST levels were positively correlated with those indices of bacterial infection. No obvious effects of medications on ALT abnormalities were found. In patients with elevated ALT, most ALT elevations were mild and transient. 59.4% of the patients had ALT concentrations of 41‐100 U/L, while only a few patients (5.2%) had high serum ALT concentrations above 300 U/L. ALT elevations occurred at 13 (10‐17) days and recovered at 28 (18‐35) days from disease onset. For most patients, the elevation of serum ALT levels occurred at 6‐20 days after disease onset and reached their peak values within a similar time frame. The recovery of serum ALT levels to normal frequently occurred at 16‐20 days or 31‐35 days after disease onset.

Conclusions

Liver function abnormalities were observed in 29.1% of elderly people COVID‐19 patients, which were slightly and transient in most cases. Liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19 may be correlated with bacterial infection.

What’s known

Liver function abnormalities were commonly observed in COVID‐19 patients.

ALT levels were found to be higher in severe COVID‐19 patients.

What’s new

Liver function abnormalities were mild and transient in most elderly COVID‐19 patients.

Liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19 may be correlated with bacterial infection.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since December 2019, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) caused by a novel coronavirus infection, 1 which was named severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), has being spreading rapidly around the world. A total of 750 890 patients have been infected and 36 405 have died worldwide as of March 31, 2020. 2 Several complications have been reported in studies of COVID‐19, among which liver function abnormalities were commonly observed. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 The reported incidence of liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19 was 14%‐53%. 7 , 8 However, the detailed characteristics and temporal changes of liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19 have not been reported. This study aims to illustrate the profile of liver function abnormalities in elderly patients with COVID‐19, which might help with clinical practice.

2. PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

2.1. Study design and participants

The patients in this retrospective study came from a case series in a descriptive study recently reported by us, 9 which included consecutive cases of COVID‐19 over 60 years old admitted from January 1 to February 6 in Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University in Wuhan, China. The diagnosis of COVID‐19 was according to the Interim guidance for novel coronavirus pneumonia established by National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China. 10 Patients without measurements of liver function were excluded. The severity of disease were classified into four groups including mild, moderate, severe and critical based on the criteria reported by the WHO‐China Joint Mission on COVID‐19. 11 This study was in accordance with the edicts of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (No. WDRY2020‐K032).

2.2. Procedures

Real‐time PCR was performed to detect the SARS‐CoV‐2 specific nucleic acid for the diagnosis of COVID‐19. Patients’ medical records were carefully reviewed and analysed by three trained physicians. Patient data including demographics, comorbidities, vital signs, medications and laboratory tests were collected. Patients were followed up till April 6 (2 months after the last admission) to collect their outcomes including survival and death. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT, upper limit of normal [ULN] < 40 units/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, ULN < 40 units/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP, ULN < 125 units/L), γ‐glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT, ULN < 60 units/L), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH, ULN < 250 units/L), total bilirubin (TBil, ULN < 23 µmol/L), direct bilirubin (DBil, ULN < 8.0 µmol/L) and albumin (ALB, normal range 40‐55 g/L) were used as indices for liver function, and their normal ranges were based on the test manual and reagent description of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0. Patients were divided into two groups (normal group and elevated group) based on their serum ALT levels during hospital stay. The normality of continuous variables was tested using the Kolmogorov‐Smirnov test. Categorical and continuous variables were summarised as counts (percentage) and median (interquartile range), respectively. Difference between two groups was tested by hypothesis testing using Mann‐Whitney U test or Chi‐squared test. Spearman correlation was used to evaluate the correlations between aminotransferases and other variables. All significance levels were computed for two‐tailed testing and the cutoff of significance was set at P < .05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics, clinical characteristics and laboratory findings

Among the 330 included patients, elevated ALT levels during hospitalisation were found in 96 (29.1%) cases and they were classified into the elevated group, while the rest 234 cases with normal ALT levels were categorised into the normal group. As described in Table 1, there were significantly fewer females (40.6% vs 54.7%, P = .020) and more critical cases (30.2% vs 19.2%, P = .026) in the elevated group compared with the normal group. No significant difference in age, incidences of common comorbidities and days from onset to admission was found between the two groups. The mortality in the elevated group was not significantly different from that in the normal group. In addition, no evident difference in vital signs on admission including heart rate, blood pressure and respiration rate was observed between the two groups. The highest body temperatures during the whole cause of disease were compared between the two groups and no difference was found, either.

TABLE 1.

Demographics, clinical characteristics and vital signs in patients with normal or elevated alanine aminotransferase

| Variables | Alanine aminotransferase | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 234) | Elevated (n = 96) | ||

| Age, y, median (IQR) | 69 (65‐77) | 69 (64‐76) | .355 |

| Female gender | 128 (54.7) | 39 (40.6) | .020 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 101 (43.3) | 35 (36.5) | .418 |

| Coronary artery disease | 28 (12) | 18 (18.8) | .226 |

| Heart failure | 6 (2.6) | 3 (3.1) | .783 |

| Diabetes | 41 (17.6) | 12 (12.5) | .423 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 10 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) | .507 |

| Chronic liver disease | 2 (0.9) | 2 (2.1) | .537 |

| Malignancy | 14 (6) | 1 (1) | .118 |

| Disease onset to admission, days, median (IQR) | 10 (7‐13) | 11 (8‐15) | .071 |

| Severity of disease | |||

| Moderate | 78 (33.3) | 20 (20.8) | .026 |

| Severe | 111 (47.4) | 47 (49) | |

| Critical | 45 (19.2) | 29 (30.2) | |

| Deaths | 42 (17.9) | 23 (24) | .213 |

| Temperature a , ℃, median (IQR) | 38.4 (37.8‐38.9) | 38.5 (37.8‐39) | .699 |

| Heart rate, bpm, median (IQR) | 82 (76‐91) | 83 (78‐90) | .746 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | 130 (120‐142) | 130 (118‐141) | .504 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg, median (IQR) | 76 (70‐83) | 76 (66‐84) | .811 |

| Respiration rate, breaths per min, median (IQR) | 20 (18‐21) | 20 (18‐22) | .318 |

Continuous variables were expressed as median (IQR) and categorical variables were expressed as count (percentage).

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

The highest body temperature during the whole cause of disease.

Table 2 shows laboratory findings on admission in the normal group and elevated group. The levels of serum ALT and AST on admission were both significantly increased in the elevated group (ALT, 56 [35‐88] vs 22 [15‐30] U/L, P < .001; AST, 48 [39‐77] vs 26 [21‐35] U/L, P < .001), compared with the normal group. Significantly increased white blood cell and neutrophil counts, accompanied by significantly higher levels of serum C‐reactive protein and procalcitonin, were also observed in the elevated group, in comparison to the normal group. No significant difference in lymphocyte count, interleukin‐6 and biomarkers for kidney injury or cardiac injury was found between the two groups.

TABLE 2.

Laboratory findings in patients with normal or elevated alanine aminotransferase

| Variables | Alanine aminotransferase | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 234) | Elevated (n = 96) | ||

| White blood cells, ×109/L, median (IQR) | 5.6 (4.2‐7.9) | 6.6 (4.8‐9.3) | .007 |

| Neutrophils, ×109/L, median (IQR) | 3.9 (2.6‐6.4) | 4.9 (3.7‐7.7) | .005 |

| Lymphocytes, ×109/L, median (IQR) | 0.92 (0.61‐1.34) | 0.86 (0.54‐1.17) | .175 |

| Monocytes, ×109/L, median (IQR) | 0.42 (0.27‐0.57) | 0.43 (0.28‐0.66) | .428 |

| Eosinophils, ×109/L, median (IQR) | 0.01 (0‐0.04) | 0.01 (0‐0.03) | .230 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L, median (IQR) | 120 (109‐129) | 122 (110‐133) | .056 |

| Platelet, ×109/L, median (IQR) | 202 (153‐252) | 209 (148‐280) | .465 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L, median (IQR) | 22 (15‐30) | 56 (35‐88) | <.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L, median (IQR) | 26 (21‐35) | 48 (39‐77) | <.001 |

| Urea, mmol/L, median (IQR) | 5.3 (3.9‐8.1) | 5.8 (4.7‐7.9) | .107 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L, median (IQR) | 60 (50‐74) | 62 (51‐80) | .506 |

| Hypersensitive troponin I, ng/mL, median (IQR) | 0.009 (0.006‐0.029) | 0.011 (0.006‐0.038) | .476 |

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL, median (IQR) | 286 (109‐690) | 266 (142‐800) | .714 |

| C‐reactive protein, mg/L, median (IQR) | 47 (15‐86) | 61 (28‐104) | .013 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL, median (IQR) | 0.07 (0.04‐0.16) | 0.09 (0.06‐0.23) | .003 |

The variables were expressed as median (IQR). IQR, interquartile range; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐B‐type natriuretic peptide.

3.2. Correlations between aminotransferases and indices of bacterial infection

Spearman correlation was used to analyse the relationship between aminotransferases and indices of bacterial infection on admission (Table S1). Both serum ALT and AST were positively correlated with indices for bacterial infection including white blood cell count, neutrophil count, C‐reactive protein and procalcitonin. Specifically, serum ALT concentration was positively correlated with neutrophil count (r = .219, P < .001) and procalcitonin (r = .168, P = .003). And similar correlations with neutrophil count (r = .165, P = .003) and procalcitonin (r = .372, P < .001) were also found for serum AST concentration.

3.3. Treatments and abnormal liver function

Medications prescribed during hospital stay in patients with normal and elevated ALT levels were compared in Table 3. Compared with patients with normal ALT levels, the medications used in patients with elevated ALT levels were not significantly different, such as antivirals, antibiotics, immunomodulatory drugs and traditional Chinese medicine.

TABLE 3.

Medications in patients with normal or elevated alanine aminotransferase

| Variables | Alanine aminotransferase | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (n = 234) | Elevated (n = 96) | ||

| Oseltamivir | 111 (47.4) | 37 (38.5) | .140 |

| Arbidol | 191 (81.6) | 74 (77.1) | .346 |

| Lopinavir/Ritonavir | 7 (3) | 5 (5.2) | .329 |

| Ribavirin | 97 (41.5) | 43 (44.8) | .577 |

| Ganciclovir | 49 (20.9) | 14 (14.6) | .182 |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 53 (22.6) | 25 (26) | .510 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 140 (59.8) | 57 (59.4) | .939 |

| Cephalosporins | 103 (44) | 41 (42.7) | .828 |

| Carbopenem | 29 (12.4) | 18 (18.8) | .133 |

| Interferon | 50 (21.4) | 25 (26) | .357 |

| Gluococorticoids | 121 (51.7) | 56 (58.3) | .273 |

| Thymalfasin | 70 (29.9) | 38 (39.6) | .089 |

| Globulin | 139 (59.4) | 59 (61.5) | .729 |

| Albumin | 62 (26.5) | 31 (32.3) | .288 |

| Traditional Chinese medicine | 190 (81.2) | 75 (78.1) | .524 |

3.4. Profiles of abnormal liver function

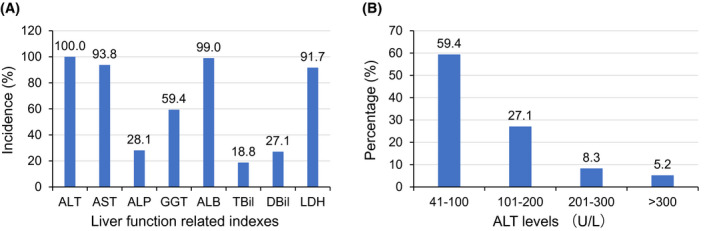

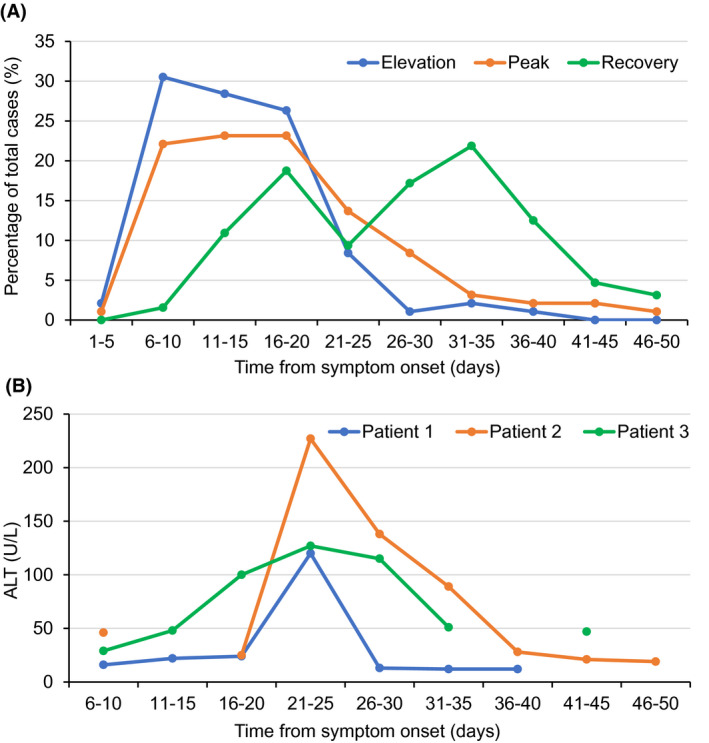

Among the 96 patients with elevated ALT, the increases of AST (93.8%), LDH (91.7%) and GGT (59.4%) during hospital stay were common (Figure 1). Hypoalbuminemia was observed in 99% of these patients. For most of the patients (59.4%), the serum ALT concentrations were 41‐100 U/L, only a few patients (5.2%) had high serum ALT concentrations above 300 U/L. The temporal characteristics of serum ALT changes were shown in Figure 2. The interval from disease onset to serum ALT elevations was 13 (10‐17) days and recovery of serum ALT levels occurred at 28 (18‐35) days from disease onset. For most of the patients, the elevation of serum ALT levels occurred at 6‐20 days after disease onset and reached their peak values within a similar time frame (Figure 2, Plot A). From 26 days after disease onset, elevations of serum ALT levels became rare. The recovery of serum ALT levels to normal range frequently occurred at 16‐20 days or 31‐35 days after disease onset. As illustrated in Plot B of Figure 2, typically the serum AST concentrations increased rapidly to their maximum and then, recovered to normal levels, with a shape of inverted “V.” And the elevation of serum ALT levels persisted for a median of 12 days (IQR 7‐17 days).

FIGURE 1.

Abnormalities in liver function related indexes. The incidences of elevated AST, ALP, GGT, TBil, DBil, LDH and decreased ALB were summarised as percentage of total cases with elevated ALT in panel A. The percentage of different ALT levels was shown in panel B. ALB, albumin; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; DBil, direct bilirubin; GGT, γ‐glutamyl transpeptidase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TBil, total bilirubin

FIGURE 2.

Temporal changes of serum ALT levels. Plot A shows the temporal distribution of serum ALT changes. The new cases of elevated ALT and recovered ALT were shown in blue and green lines, respectively. The orange line shows the cases that reach the highest concentration of serum ALT. Plot B shows typical temporal changes of serum ALT concentrations in three patients. ALT, alanine aminotransferase

4. DISCUSSION

The present study illustrates the profiles of liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19. Elevated serum ALT levels were observed in 29.1% of elderly people COVID‐19 patients in this study. There were fewer females and more critical cases in patients with elevated ALT compared with those with normal ALT levels. Higher levels of bacterial infection indices such as neutrophil count and procalcitonin were observed in the elevated group and both ALT and AST levels were positively correlated with those indices. In most cases ALT elevations were mild and transient, with ALT elevation at 13 (10‐17) days and recovery at 28 (18‐35) days after disease onset.

Liver function abnormalities were commonly observed in COVID‐19. 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 The reported incidence of liver function damage in COVID‐19 was 14%‐52% in previous studies. 7 , 8 Since ALT is the most representative index of liver injury, it was used as the basis for grouping in the present study. In the present study, 96 (29.1%) of the 330 elderly COVID‐19 patients had serum ALT elevation. There were more critical cases and more males in patients with elevated ALT. Consistent with our findings, ALT levels were found to be higher in COVID‐19 patients who needed ICU care, 6 , 12 and liver function damage was more prevalent in male gender. 13 A lower incidence of liver dysfunction (3.75%) was reported in a study focusing on the imported cases of COVID‐19 in Jiangsu province of China, 14 in which the included patients were relatively younger (median age 46.1 years) and milder (96.3% of the cases were mild or moderate) compared with the present study. Moreover, other indices related to abnormal liver function, including decreased ALB, elevated AST, LDH and GGT, were also frequently observed in patients with elevated ALT.

There are several possible mechanisms related to liver dysfunctions in COVID‐19. COVID‐19 is caused by infection of SARS‐CoV‐2, which is a new human‐infecting betacoronavirus that binds to the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor to invade human target cells, similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus. 1 , 15 Liver injury was also reported in patients with SARS. 16 , 17 Single cell sequencing revealed that ACE2 was mainly expressed in cholangiocytes, while scarcely expressed in hepatocytes, 13 suggesting that the virus might directly bind to ACE2 positive cholangiocytes, thus cause the liver function abnormalities. Alterations of systemic inflammation and immunity were also supposed to be responsible for the liver dysfunction in COVID‐19. 8 , 13 Lymphopenia occurred within the first 2 weeks of illness in SARS patients. 18 Likewise, in severe cases with Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which was induced by another coronavirus (MERS‐CoV), serum levels of cytokine and chemokine also elevated in the early 2 weeks. 19 In the present study, most of the ALT elevations were begin within 1‐3 weeks after symptoms onset. These temporal correlations may indicate a possible involvement of immune disorders and inflammation in the damage of liver function. However, the detail mechanisms need to be further investigated. Hypoxemia may also be a cause of liver damage. 20 Hypoxemia induced by pneumonia is one of the main features of COVID‐19, the degree of hypoxemia is used as the clinical classification criterion for COVID‐19 patients. In the present study, there were more severe cases in patients with elevated ALT, indicating the possible influence of hypoxemia on liver damage. In addition, bacterial infection may play a role in liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19. The cytokines, reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide released by Kupffer cells, which help to clear the bacteria and endotoxins invading into the portal vein system, might cause injury of the hepatocytes. And cytokines produced by neutrophils could induce further hepatocyte damages. 21 In the present study, indices of bacterial infection were significant higher in the patients with elevated ALT, including the counts of white blood cells and neutrophils, serum C‐reactive protein and procalcitonin levels. And significant positive correlations were found between those indices and aminotransferases. These results suggested a close relationship between bacterial infection and liver function abnormalities. Furthermore, medications such as antivirals or antibiotics may cause damage to liver function. However, no significant difference in medications was found between patients with normal and elevated ALT levels in the present study. It should be noted that there was a high proportion of male genders in patients with elevated ALT, which may be related to the gender differences in ACE2 expression or lifestyles such as smoking. However, more research is needed to elucidate this phenomenon.

Characteristics of liver dysfunction caused by coronavirus infection have been reported in several studies. ALT elevation in SARS patients occurred during the first 2 weeks after disease onset, 16 , 22 and started to recover after 2 weeks. 22 Most of the liver injuries in SARS patients were mild or moderate. 7 , 16 Increases of ALT, AST and LDH were also noted in patients with MERS. 23 In a transgenic mouse model of human dipeptidyl peptidase‐4, the receptor of MERS‐CoV, mild to moderate liver damage was observed on day 5 after infection with MERS‐CoV. 24 In the present study, we showed that most of the ALT abnormalities in elderly COVID‐19 patients were mild and transient, too. In 96 patients with abnormal liver function, 59.6% were mild (1‐2.5 times the ULN, 41‐100 units/L), while only 12.8% were beyond five times the ULN (200 units/L). Considering the temporal changes of ALT levels, the elevation of ALT mostly occurred within 3 weeks from disease onset and recovered within about 5 weeks.

4.1. Limitations

Several limitations should be noted for this study. As a retrospective study, the indices for liver functions were not determined with a fixed time interval. In addition, the medications taken before admission such as antivirals were difficult to retrieve, which might contribute to the liver function abnormalities on admission.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Liver function abnormalities were observed in 29.1% of elderly people COVID‐19 patients, which were slightly and transient in most cases. Liver function abnormalities in COVID‐19 may be correlated with bacterial infection.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by Grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81570450, 81900455).

Yu X, He W, Wang L, et al. Profiles of liver function abnormalities in elderly patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e13632. 10.1111/ijcp.13632

Xiaomei Yu and Wenbo He have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Lang Wang, Email: wlang81@126.com.

Hong Jiang, Email: hong-jiang@whu.edu.cn.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565‐574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Situation Report‐71; 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20200331‐sitrep‐71‐covid‐19.pdf?sfvrsn=4360e92b_8. Accessed March 21, 2020.

- 3. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708‐1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single‐centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475‐481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xu L, Liu J, Lu M, Yang D, Zheng X. Liver injury during highly pathogenic human coronavirus infections. Liver Int. 2020;40:998‐1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang C, Shi L, Wang FS. Liver injury in COVID‐19: management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:428‐430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang L, He W, Yu X, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4‐week follow‐up. J Infect. 2020;80:639‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Health Commision of the People's Republic of China . Interim guidance for novel coronavirus pneumonia (Trial Implementation of Sixth Edition). http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 11. World Health Organization . Report of the WHO‐China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019. https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/who‐china‐joint‐mission‐on‐covid‐19‐final‐report. Accessed March 5, 2020.

- 12. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xie H, Zhao J, Lian N, Lin S, Xie Q, Zhuo H. Clinical characteristics of Non‐ICU hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and liver injury: a retrospective study. Liver Int. 2020;40:1321‐1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wu J, Liu J, Zhao X, et al. Clinical characteristics of imported cases of COVID‐19 in Jiangsu Province: a multicenter descriptive study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:706‐712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheng H, Wang Y, Wang GQ. Organ‐protective effect of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 and its effect on the prognosis of COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020;92:726‐730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu KL, Lu SN, Changchien CS, et al. Sequential changes of serum aminotransferase levels in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;71:125‐128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang Z, Xu M, Yi JQ, Jia WD. Clinical characteristics and mechanism of liver damage in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2005;4:60‐63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu M. SARS Immunity and vaccination. Cell Mol Immunol. 2004;1:193‐198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim ES, Choe PG, Park WB, et al. Clinical progression and cytokine profiles of middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1717‐1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ebert EC. Hypoxic liver injury. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1232‐1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Woznica EA, Inglot M, Woznica RK, Lysenko L. Liver dysfunction in sepsis. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2018;27:547‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cui HJ, Tong XL, Li P, et al. Serum hepatic enzyme manifestations in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: retrospective analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1652‐1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Assiri A, Al‐Tawfiq JA, Al‐Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752‐761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao G, Jiang Y, Qiu H, et al. Multi‐organ damage in human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 transgenic mice infected with middle east respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0145561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1