Abstract

Background and aims

Children with extremely low‐birth weight (ELBW) have a high risk for cognitive, motor, and attention impairments and learning disabilities. Longitudinal follow‐up studies to a later age are needed in order to increase understanding of the changes in neurodevelopmental trajectories in targeting timely intervention. The aims of this study were to investigate cognitive and motor outcomes, attention‐deficit hyperactivity (ADHD) behaviour, school performance, and overall outcomes in a national cohort of ELBW children at preadolescence, and minor neuromotor impairments in a subpopulation of these children and to compare the results with those of full‐term controls. The additional aim was to report the overall outcome in all ELBW infants born at 22 to 26 gestational weeks.

Methods

This longitudinal prospective national cohort study included all surviving ELBW (birth weight <1000 g) children born in Finland in 1996 to 1997. No children were excluded from the study. Perinatal, neonatal, and follow‐up data up to the age of 5 years of these children were registered in the national birth register. According to birth register, the study population included all infants born at the age under 27 gestational weeks. At 11 years of age general cognitive ability was tested with the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, ADHD behavior evaluated with a report from each child's own teacher (ADHD Rating Scale IV), and school performance with a parental questionnaire. An ELBW subpopulation consisting of a cohort representative children from the two university hospitals from two regions (n = 63) and the age‐matched full‐term born controls born in Helsinki university hospital (n = 30) underwent Movement Assessment Battery for Children and Touwen neurological examination comprising developmental coordination disorder (DCD) and minor neurological dysfunction (MND), respectively.

Results

Of 206 ELBW survivors 122 (73% of eligible) children and 30 (100%) full‐term control children participated in assessments. ELBW children had lower full‐scale intellectual quotient than controls (t‐test, 90 vs 112, P < .001), elevated teacher‐ reported inattention scores (median = 4.0 vs 1.0, P = .021, r = .20) and needed more educational support (47% vs 17%, OR 4.5, 95% CI 1.6‐12.4, P = .02). In the subpopulation, the incidences of DCD were 30% in ELBW and 7% in control children (P = .012, OR 6.0 CI 1.3‐27.9), and complex MND 12.5% and 0%, (P = .052; RR 1.1 95% CI 1.04‐1.25), respectively. Of survivors born in 24 to 26 gestational weeks, 29% had normal outcome.

Conclusion

As the majority of the extremely preterm born children had some problems, long‐term follow‐up is warranted to identify those with special needs and to design individual multidisciplinary support programs.

Keywords: attention deficit disorder, developmental problems, very preterm infant

Abbreviations

- ADD

attention deficit disorder

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ADHD

RS ADHD Rating Scale

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CI

confidence interval

- cMND

complex minor neurological dysfunction

- CP

cerebral palsy

- DCD

developmental coordination disorder

- ELBW

extremely low birth weight

- FSIQ

full‐scale intelligence quotient

- GW

gestational week

- IQ

intellectual quotient

- IQR

interquartile range

- IVH

intraventricular haemorrhage

- MABC

movement assessment battery for children

- NEC

necrotising enterocolitis

- ns

not significant

- OR

odds ratio

- PDA

persistent ductus arteriosus

- ROP

retinopathy of prematurity

- RR

risk ratio

- SD

standard deviation

- SGA

small for gestational age

- sMND

simple minor neurological dysfunction

- WISC

the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children

- WPPSI‐R

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence‐Revised

1. INTRODUCTION

In children born extremely preterm (before 28 GW) 1 or with extremely low‐birth weight (ELBW, less than 1000 g), 2 the risk of long‐term neurocognitive problems affecting daily life is high. Deficits in attention and executive functions, neuromotor problems, learning difficulties, behavioural and emotional impairment, deficits in intelligence, and poor growth are frequently reported disabilities. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 It is important to identify these long‐term consequences as they will lead to adverse effects, not only for the child but also for the family and relatives, and moreover for health service providers, school education plans, and society.

Major disabilities are usually diagnosed in early childhood, 4 , 5 but many minor neurodevelopmental impairments may not be detected before school age, when demands of cognitive and motor skills increase. A recent meta‐analysis on studies between the 1990s and 2008, including a follow‐up until 5 or more years, showed that preterm infants had a 0.85 SD lower intelligence quotient (IQ) than full‐term control children in various standardized, validated intelligence tests, including full‐scale, verbal, and performance measures. 1 The cognitive disabilities were as common in 2008 as in 1990s. 1 One reason to similar prevalence of cognitive disability despite considerable development in care can be ascribed to the increasing survival of the most immature infants, especially of those born at 23 and 24 GW. 6 With improvement of perinatal and neonatal care, long‐term follow‐up of new population‐based cohorts are continuously needed.

The incidence of cerebral palsy (CP) is declining in several countries. 7 , 8 However, an increased rate of non‐CP motor impairment was reported in Australia. 3 In school‐aged children born extremely preterm, there are only a few reports on developmental coordination disorder (DCD). 9 In the studies included in a systematic review, 9 the prevalence of DCD measured with the movement assessment battery for children (MABC) varied between 9.5% and 72% in ELBW children compared to 2% to 22% in control children when the total score below the fifth centile was used as cut‐off limit.

In the current national ELBW cohort born in Finland 1996 to 1997, perinatal and follow‐up data up to 5 years of age have been collected in a research register and published. 10 , 11 , 12 The aims of this study were to assess cognitive and neuromotor outcome, attention‐deficit hyperactivity (ADHD) features, and school progression in survivors of the population‐based cohort of ELBW children at age 11 years, and to compare these results with those of same‐aged children born healthy at term. In addition, a subpopulation consisting of a cohort representative children from the two university hospitals was assessed in more detail. By including all infants, both those who are stillborn and those who are born alive, we aimed to report the pregnancy outcome for an extreme preterm birth in terms of survival and long‐term neurocognitive outcome.

2. SUBJECTS AND METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The study population consisted of all surviving ELBW children with a birth weight less than 1000 g and a gestational age of at least 22 completed weeks born in Finland during a 2‐year study period (January 1st, 1996 to December 31st, 1997). The birth weight‐based criterion was chosen to be able to compare with other similar studies 13 and to enable inclusion of all extremely preterm infants with a gestational age less than 27 GW, including also stillbirths. 10

A subpopulation investigated in more detail consisted of surviving children in two regions, the Helsinki University Hospital (n = 90) from where one third of the national cohort came, and Oulu University Hospital (n = 31), the Northernmost hospital in the country.

2.1.1. Control group

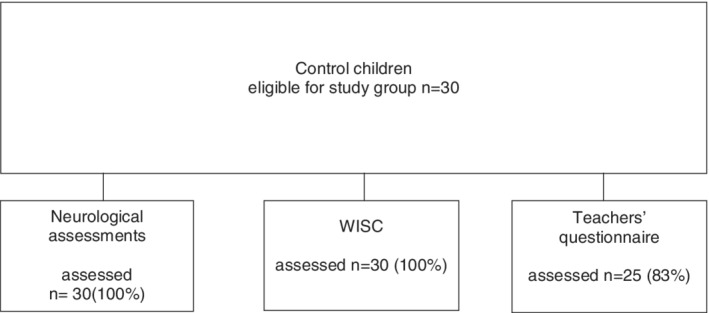

The control group consisted of randomly selected children from Population Information System of Finland participating in standardization of the neurodevelopmental test NEPSY II. These children were invited by letter to the present study by two of the researchers. In addition, control children were invited by letter from a local elementary school in Helsinki, and children of personnel of Helsinki University Hospital (Figure 2). The control children were born full‐term with a birth weight more than 2500 g, with no need for neonatal care, age‐matched with study children at the age of 11 years, and all living in the capital area. The controls were not matched by sex. No compensation was given to the families.

Figure 2.

Control children participating in the study

2.1.2. Data collection procedures, methods, and definitions

Perinatal and neonatal data were obtained for all ELBW children from maternity hospitals by a questionnaire and were cross‐linked with the Finnish National Birth Register. The methods and definitions of earlier follow‐up assessments have been described in detail in previous publications. 10 , 11 , 12 The definitions for gestational age, intrauterine growth restriction, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotising enterocolitis, intraventricular haemorrhage, retinopathy of prematurity, and septicaemia, are defined in previous publications of this cohort. 10 , 11 , 12 The use of supplementary oxygen was recorded at the age corresponding to 36 GWs.

Severe visual impairment was defined as visual acuity of less than 20/200, hearing impairment as a need for hearing aid, and CP was defined as a permanent nonprogressive central motor dysfunction affecting muscle tone, posture, and movement. 14 Data on CP and severe visual impairment at the age of 1.5 and 5 years were obtained from hospitals responsible for follow‐up, the national discharge register, and the national visual impairment register. All data were registered in the national ELBW infant register, a part of the national birth register in National Institute for Welfare and Health.

An invitation letter was sent to all families, including a questionnaire concerning their child's school achievement, informed consent forms for the parents and the child to participate in the study, and to give permission for the study nurse/assistant to phone them in case that they and their child would not participate in the study. In phone call, the study assistant collected information of reasons why some families did not want to participate in the study.

Cognitive performance was assessed using the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children ‐ third edition (WISC‐III). 15 WISC‐IV had not been standardized and in use for Finnish population. Based on the full‐scale intelligence quotient (FSIQ), cognitive impairment was divided into severe (below 55), moderate (ranging from 55 to 69), and mild (ranging from 70 to 85).

School behavior was assessed with the teacher‐completed ADHD Rating Scale IV (ADHD RS‐IV 16 ) which each child gave to his/her own class teacher who send it to the research assistant. ADHD RS‐IV includes 18 items of hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention. The total score and summary scores for hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention of ELBW children were compared with those of control children. Information of school performance and the need for special education in reading, writing, or mathematics, for special class teaching or for postponed school start was obtained from parents.

Overall outcome was graded as (a) severely impaired, if the child had either severe CP, blindness, deafness, FSIQ ≤70, a combination of these, or any CP and severe problems with vision or school attendance; (b) moderately impaired, if the child had none of the above mentioned impairments but FSIQ was between 70 and 84; and (c) normal, if FSIQ was 85 or above.

Motor and neurological assessments of the subpopulation and controls were performed at Helsinki and Oulu University Hospitals by three child neurologists and one neonatologist. The MABC, the first edition, was chosen as MABC2 was not in use in Finland at the time a follow‐up was carried out. MABC is composed of three parts: manual dexterity, ball skills, and static and dynamic balance. 17 It was used to grade motor impairment as DCD (total score below the 5th percentile) and as probable DCD (total score at 5th to 15th percentiles).

The age‐specific qualitative Touwen Neurological Examination focuses on the domains of posture and muscle tone, reflexes, coordination and balance, fine manipulative ability, cranial nerve function, and involuntary and associative movements. 18 The children were classified as having a simple minor neurological dysfunction (sMND; one or two dysfunctional domains), or a complex MND (cMND; three or more dysfunctional domains).

2.1.3. Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were made by IBM SPSS Statistic program (version 22 and 25). Pearson chi‐square test/Fisher's exact test (for comparison of background information between participating and nonparticipating children and between the subpopulation and other ELBW children in the study group, proportions of normal WIPPSI‐scores, school and neuromotor outcome between the study and the control group), Mann Whitney U test (for ADHD rating scale and comparison of WIPPS‐R‐scores at the age of 5 years between participating and nonparticipating children and between the subpopulation and other ELBW children in the study group), and Student's t‐test (for comparison of WISC‐III scores between study group and the controls) were used in analyses. P‐values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Effect sizes (Cohen's d and r) were interpreted as small (d < 0.50, r < .10), medium (d < 0.80, r < .30), or large (d ≥ 0.80, r ≥ .50).

2.1.4. Ethics

The study was approved by the research ethics committees of the Hospital for Children and Adolescents and the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Helsinki University Hospital, by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, and by the Data Protection Ombudsman. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents and children before assessments.

3. RESULTS

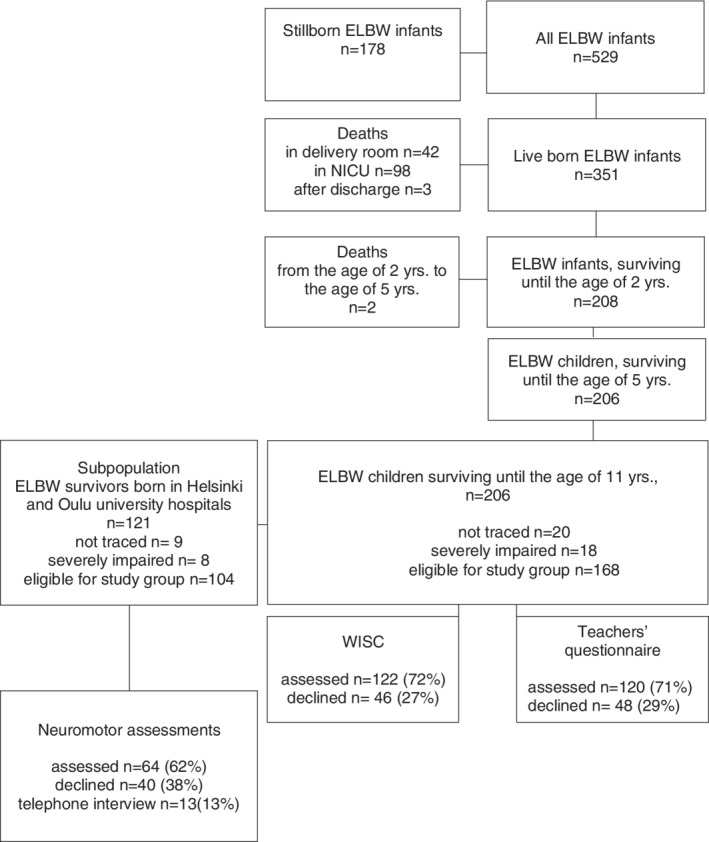

Of the entire ELBW study population (N = 529), 351 (66%) were born alive and 206 (59%) survived until 11 years of age (Figure 1). For this follow‐up, a total of 20 children (10% of survivors) were lost to follow‐up, five of them being nonresidents. Eighteen children (9% of the survivors) with severe cognitive impairment could not be assessed and were excluded from the analysis. Of the remaining 168 children eligible for the study, 104 (62%) participated in all parts of the investigation, 43 (26%) in most parts, 13 (8%) were interviewed by phone, and 8 (5%) families refused to participate. The numbers of children attending in each part of the study are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Extremely low birth weight born children participating in each part of the study

A subpopulation investigated in more detail consisted of surviving children in two regions, the Helsinki University Hospital (n = 90) and Oulu University Hospital (n = 31; Figure 1). The comparison of the subpopulation with the rest of the cohort showed that it is representative of the whole ELBW cohort. In the subpopulation, nine families (7%) were lost to follow‐up and eight children (7%) were severely impaired. Of the 104 children eligible for the study, 63 children (61%) participated in the neuromotor examination. Of the remaining 41 children 3 did not attend the study at all, the rest participated in other parts of the study.

The median age at the assessment was 11.3 (range from 10.6 to 13.9, IQR 8.3) years in the study group and 11.8 (range from 10.7 to 13.8, IQR 9.8) years in the control group.

No differences were found in the perinatal data of those who participated at the age of 11 years and those who did not, neither between the subpopulation and the rest of the ELBW children (Tables 1 and 2). Children, whose severe disability prevented them from being assessed, were excluded from the analysis (n = 18). The verbal IQ and FSIQ in Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence‐Revised at 5 years of age was higher in the 11‐year participants than in nonparticipants (Table 1). The performance IQ, but not FSIQ, of the subpopulation was significantly higher than those of the rest ELBW children (Table 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of background information between participating and nonparticipating children

| Children participating n = 122 a | Children not participating n = 66 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal steroid treatment (%) | 80 | 83 | .702 |

| Born in tertiary hospital (%) | 88 | 93 | .376 |

| Maternal age (years) | 31.9 | 31.0 | .367 |

| Maternal university education (%) | 15 | 10 | .393 |

| Mean gestational age (weeks) | 27.3 | 27.6 | .441 |

| Mean birth weight (g) | 802 | 815 | .584 |

| SGA b (%) | 50 | 59 | .353 |

| Male gender (%) | 44 | 46 | .749 |

| Multiple birth infants (%) | 25 | 29 | .597 |

| 5‐minute Apgar scores <4 (%) | 7 | 7 | .936 |

| RDS c (%) | 69 | 63 | .432 |

| NEC d (%) | 5 | 5 | .982 |

| Septicaemia (blood culture positive) (%; %) | 28 | 22 | .433 |

| PDA (surgically treated) e (%) | 8 | 7 | .833 |

| IVH f (grades III‐IV; %) | 6 | 5 | .787 |

| Supplementary oxygen at age of 36 GWs (%) | 38 | 27 | .183 |

| ROP g (stages III‐V; %) | 10 | 5 | .293 |

| WPPSI‐R h at the age of 5 years (Full‐Scale IQ) | 98.7 (n = 110) | 89.7 (n = 35) | .026 |

| WPPSI‐R at the age of 5 years (Verbal IQ) | 96.1 (n = 112) | 90.5 (n = 35) | .027 |

| WPPSI‐R at the age of 5 years (Performance IQ) | 96.2(n = 111) | 92.9 (n = 36) | .364 |

| Cerebral palsy at the age of 5 years (%) | 11 (n = 121) | 6 (n = 60) | .352 |

| Head circumference at the age of 5 years (SD) | −1.1 (n = 95) | −1.1 (n = 31) | .987 |

Note: Severely impaired children are (n = 18) excluded. Chi‐square statistic is used in analyses.

Number includes also those partly participating in the study. Data of neonatal characteristics was obtained for all children. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of children studied.

SGA, small for gestational age.

RDS, respiratory distress syndrome.

NEC, necrotising enterocolitis.

PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus.

IVH, Intraventricular haemorrhage.

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

WPPSI‐R, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Revised.

Table 2.

Comparison of background information between the subpopulation and other ELBW children in the study group

| Subpopulation of ELBW study group n = 63 | ELBW children except the severely disabled and those who belong to subgroup n = 125 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antenatal steroid treatment (%) | 79 | 82 | .713 |

| Born in tertiary hospital (%) | 90 | 88 | .611 |

| Maternal age (years) | 31.8 | 31.7 | .938 |

| Maternal university education (%) | 14.1 | 18.3 | .494 |

| Mean gestational age (weeks) | 27.4 | 27.3 | .876 |

| Mean birth weight (g) | 815 | 800 | .483 |

| SGA a (%) | 54 | 51 | .720 |

| Male gender (%) | 52 | 40 | .107 |

| Multiple birth infants (%) | 19 | 30 | .120 |

| 5‐minute Apgar scores <4 (%) | 8 | 7 | 1.000 |

| RDS b (%) | 67 | 69 | .767 |

| NEC c (%) | 8 | 3 | .165 |

| Septicaemia (blood culture positive; %) | 32 | 24 | .275 |

| PDA (surgically treated) d (%) | 6 | 9 | .548 |

| IVH e (grades III‐IV; %) | 5 | 6 | .754 |

| Supplementary oxygen at age of 36 GWs (%) | 35 | 36 | .884 |

| ROP f (stages III‐V; %) | 11 | 8 | .483 |

| WPPSI‐R g at the age of 5 years (Full‐Scale IQ) | 101 (n = 62) | 97 (n = 78) | .143 |

| WPPSI‐R at the age of 5 years (Verbal IQ) | 103 (n = 62) | 102 (n = 78) | .848 |

| WPPSI‐R at the age of 5 years (Performance IQ) | 100 (n = 62) | 93 (n = 80) | .007 |

| Cerebral palsy at the age of 5 years (%) | 6 (n = 63) | 12 (n = 117) | .219 |

| Head circumference at the age of 5 years (SD) | −1.2 (n = 42) | −1.1 (n = 69) | .638 |

SGA, small for gestational age.

RDS, respiratory distress syndrome.

NEC, necrotising enterocolitis.

PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus.

IVH, Intraventricular haemorrhage.

ROP, retinopathy of prematurity.

WPPSI‐R, Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence – Revised.

3.1. Cognition

In WISC‐III, the mean FSIQ of 122 ELBW children was significantly lower (90 ± 20) than that of the control children (112 ± 14; t[148] = 6.6, P < .001, d = 1.1). The performance IQ in the study group was 85 ± 23 vs 110 ± 14 in controls (t[150] = 5.7, P < .001, d = 1.2), and the verbal IQ was 96 ± 21 vs 115 ± 22, respectively, (t[148] = 4,3, P < .001, d = 0.9). Of the assessed ELBW children, 24 (20%) had mild, 17 (14%) moderate, and 4 (3%) severe cognitive impairment. All control children had FSIQ of 85 or higher and thus were classified as normal. Altogether, 62% of the ELBW children (n = 76) had FSIQ within the normal range, a significant difference (P < .001 RR 1.6, 95%CI 1.4‐1.8), however, compared to the control children.

3.2. School data

Information on school achievement was available for 155 children in the ELBW group and all control children. Seventy‐four (47%) ELBW children and 5 (17%) control children received support in their school attendance (P = .002 OR 4.5, 95%CI 1.6‐12.4). A total of 35 (23%) in the ELBW group in comparison to none in the control group (P = .004, RR 1.3, 95% CI 1.2‐1.4) attended special needs education for children with learning impairment. For 30 (19%) ELBW children and for one (3%) control child the beginning of school attendance had been postponed for 1 year (P = .032, OR 6.9, 95 %CI 0.9‐52.7). Additionally, 26 (17%) vs 2 (7%) children, respectively, received part‐time support for reading and writing (P = .262, OR 2.8 95 %CI 0.63‐12.49), and 22 (14%) vs 2 (7%) needed other targeted assistance for their studies (P = .378, OR 2.3 95 %CI 0.52‐10.42).

The ADHD RS‐IV results showed that teachers reported higher inattention scores in ELBW children (median = 4.0, IQR = 7.0.) than in control children (median = 1.0, IQR = 2.5), U = 1745.00, z = 2.3, P = .021, r = .20). However, there were no group differences in the hyperactivity/impulsivity score (median = .0, IQR = 1.0 vs median = 1.0, IQR = 3.5; U = 1241.00, z = −1.1, P = .267, r = −.09) or the total score of ADHD RS‐IV (median = 5.0, IQR = 8.0 vs median = 2.0, IQR = 4.0; U = 1575.00, z = 1.4, P = .159, r = .12).

3.3. Overall outcome

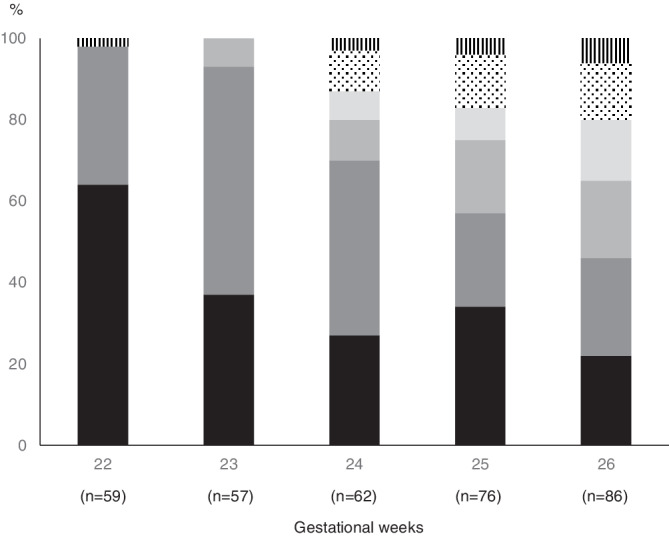

Of all births in GW 22 (n = 59) and GW 23 (n = 57), no child had a normal cognitive development at 11 years of age. From GW 24 (n = 62) on, the rate of stillbirths decreased and the number of children with normal neurocognitive development increased with increasing GA (Figure 3). One third of those born at the age of 24 to 26 GWs had no severe hearing or visual impairment or CP, and had normal cognitive outcome or were attending normal school without any support, and 53% of those born at the age of 27 to 30 GWs were classified as normal according to the same criteria.

Figure 3.

The overall outcome at the age of 11 years in extremely low‐birth weight infants born in Finland in 1996 to 1997

3.4. Neuromotor outcome

In the subpopulation, in the MABC‐test, 18 of 60 (30%) ELBW and 2 of 30 (7%) control children had DCD (P = .012, OR 6.0, 95% CI 1.3‐27.9), and 33 (55%) and 9 (30%), respectively, had probable DCD (P = .025, OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.1‐7.2).

In the Touwen examination, 8 of 64 (12.5%) ELBW children but none of the control children (n = 30) had cMND (P = .052; RR 1.1 95% CI 1.04‐1.25), and sMND was found in 25 (39%) ELBW children and in 7 (23%) control children (P = .134; OR 2.1 95% CI 0.79‐5.63).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we assessed the long‐term outcome of a national birth cohort with a birth weight less than 1000 g. One third of ELBW preadolescents had below average full‐scale IQ, and compared to the age matched controls, they had greater incidences of neuromotor dysfunction, more teacher reported inattention problems and they needed more educational support at school in accordance of earlier research. 1 , 2 , 5 None of the deliveries in GW 22 or 23 was compatible with a fully normal neurocognitive development at preadolescent age. From 24 GW on, the rate of outcome without any observed impairments increased, being 29% in surviving children born at 24 to 26 GWs.

The high mortality and disability rate in 22 and 23 GW children may be explained by the perinatal and neonatal care. In the 1990s, proactive care of pregnancies less than 24 GW was not considered clinical routine in Nordic countries. After the millennium shift, a more proactive care was applied for these very immature births. 6 As shown in the Swedish EXPRESS‐study including a national cohort of all births below 26 GW in 2004‐2007 with a proactive approach in majority of deliveries and newborn infants, the rate of stillbirth and 1‐year mortality were considerably lower than in comparable studies. 6 Despite the high survival rate, the disability rate at 6.5‐years of age was similar to other national studies, with no disabilities in 36% and mild in 30%. 19 Our findings in GW 24 to 26 are in line with that, showing that there is a need to thoroughly assess ELBW infants at preschool and school age to identify aberrations in development.

As expected, the ELBW children showed more impairment in cognitive functions and needed more educational support at school than children in the control group. 1 The incidence of postponed school attendance (starting school a year later) in the Finnish population is approximately 2%, 20 and approximately 7% of comprehensive school pupils need special education, 21 both incidences being similar as in our control group. Although country‐specific differences in school systems are noteworthy and, therefore, comparison of school performance between studies is difficult, poor academic achievement seems to be common in preterm born children. 22 In our study, small group size may explain why differences in need for support in reading and writing between the ELBW and control group were not statistically significant.

In our study, ELBW children had elevated scores for inattention, reported by teachers, while scores related to hyperactive or impulsive behavior were similar to those of the controls. Parents seem to underestimate the problems of their ELBW child. 23 Likewise, a Swedish study showed that teachers and parents poorly recognize intellectual problems in preterm born children. 24 This might deteriorate the child's performance at school and complicate the planning of rehabilitation. Bullying at school is more directed to ELBW children than to their peers and is associated with occurrence of impairments such as intellectual problems, functional limitations, ADHD, having few friends, and poor friend connection. 25 , 26 Bullying causes many psychosomatic problems, 27 which may increase pre‐existing school problems and the challenge of teaching and teachers. 28

At the age of 11 years, neuromotor problems were common in the surviving ELBW children. One third of our cohort had a DCD. It is within the wide variation of DCD rate observed in the few other studies which have used the MABC test as a diagnostic measure in school aged children. 9 In a Swedish study, especially teenage ELBW boys performed significantly poorer than their peers on the MABC test. 29 As we did not include DCD questionnaires as supplementary information of daily functioning, we used a strict MABC cut‐off criterion below the fifth centile consistent with DCD in order to be certain that we have identified correctly the children with DCD, and to be able to compare DCD rates with other studies.

In a Dutch study on full‐term children, 30 the incidences of sMND and cMND at the age of 9 years were as high as in the ELBW subpopulation in our study. However, it is unclear if the quality and significance of minor aberrations in motor functions, their duration, and consequences on everyday life are different in preterm and full‐term children. In preterm children impairments in motor performance tend to be permanent rather than transient. 31

As common in long‐term follow‐up studies, one limitation in our study was that we did not achieve complete data for all children. We used several ways to obtain data about the whole study cohort. Most of those children not assessed at all (15%) were from families that could not be traced. Parents of 13 (8%) children were interviewed by phone, because the children themselves declined to participate. Of the original study survivors, for 77% some assessment data were obtained, which is a similar rate to that observed in other recent population‐based studies. 29 , 32 In a systematic review including 20 studies with a follow‐up duration between 18 and 24 months, higher loss to follow‐up was associated with higher rates of neurodevelopmental impairment in assessed children. 33 The authors suggested that the parents of the healthiest children were not interested in assessments, as the families were not worried about their child's health or development. 33 On the other hand, families with disabled children may be less interested in additional developmental assessments for research purposes. In this study, the children lost to follow‐up had a lower 5‐years IQ than participants did. However, there were several reasons identified for the nonparticipation such as not traced, child declining, parents' work duties, and long distances. Thus, the nonassessed group was heterogeneous and, in our opinion, unlikely to cause a systematic bias.

Another limitation is the small control group. This group, however, consisted of randomly selected full‐term Finnish children presenting as preadolescents with normal school performance in the capital area. However, no control child was enrolled from the northern part of Finland, where one quarter of the subpopulation were living. In detailed analysis of results in Pisa tests, an internationally standardized student assessment, geographical differences have not been statistically significant in different parts of Finland or between urban and rural areas. 34 In addition, socioeconomical differences in Finland had little effect in learning for example in literacy. The effect was smaller than that in the most OECD countries. 34 For practical reasons, neurologic examinations were performed only in two university hospital areas with similar characteristics in the children as in the entire cohort.

5. CONCLUSION

Our study shows that children born preterm have, in addition to major disabilities, minor impairments in multiple developmental domains. Minor neurodevelopmental problems, for example, symptoms of inattention, are difficult to detect without thorough assessments. For both health care providers and the school organization, the challenge is to identify the children with minor neurodevelopmental problems early enough to provide adequate educational and psychosocial support. As only about one third of the surviving ELBW infants in this study and also in the Swedish cohort one decade later, 6 was considered fully normally developing, a long‐term follow‐up is necessary for all extremely immaturely born children to enable adequate support before additional learning, behavioural, emotional, and social problems arise.

FUNDING

This study has been supported by grants from Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation and Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa (to VF). These financial supports have been used for the researcher grants to enable the researchers to work full‐time for some months.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they do not have conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Concept and design: All authors.

Conceptualization: Viena Tommiska, Päivi Kleemola, Liisa Klenberg, Aulikki Lano, Liisa Lehtonen, Tuija Löppönen, Päivi Olsen, Outi Tammela, Vineta Fellman

Data Aquisation and Curation: Viena Tommiska, Päivi Kleemola, Liisa Klenberg, Aulikki Lano, Liisa Lehtonen, Tuija Löppönen, Päivi Olsen, Outi Tammela, Vineta Fellman

Formal Analysis: Viena Tommiska, Päivi Kleemola, Aulikki Lano

Funding Acquisition: Vineta Fellman

Methodology: Viena Tommiska, Liisa Klenberg, Aulikki Lano, Vineta Fellman

Supervision: Vienta Fellman

Writing ‐ Original Draft Preparation: Viena Tommiska, Liisa Klenberg, Aulikki Lano, Vineta Fellman

Writing ‐ Review & Editing: Viena Tommiska, Päivi Kleemola, Liisa Klenberg, Aulikki Lano, Liisa Lehtonen, Tuija Löppönen, Päivi Olsen, Outi Tammela, Vineta Fellman

Viena Tommiska, Vineta Fellman and Päivi Kleemola had full access to all of the data in the study and takes complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

Viena Tommiska affirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express our sincere gratitude to late professor Marit Korkman for her significant contribution in initiation and implementation of this study.

Tommiska V, Lano A, Kleemola P, et al. Analysis of neurodevelopmental outcomes of preadolescents born with extremely low weight revealed impairments in multiple developmental domains despite absence of cognitive impairment. Health Sci Rep. 2020;3:e180 10.1002/hsr2.180

Funding information Signe and Ane Gyllenberg Foundation and Medicinska Understödsföreningen Liv och Hälsa (to VF).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

REFERENCES

- 1. Twilhaar ES, Wade RM, de Kieviet JF, van Goudoever JB, van Elburg RM, Oosterlaan J. Cognitive outcomes of children born extremely or very preterm since the 1990s and associated risk factors: a meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(4):361‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lundequist A, Böhm B, Lagercrantz H, Forssberg H, Smedler AC. Cognitive outcome varies in adolescents born preterm, depending on gestational age, intrauterine growth and neonatal complications. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(3):292‐299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spittle AJ, Cameron K, Doyle LW, Cheong JL, Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group . Motor impairment trends in extremely preterm children: 1991‐2005. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fjørtoft T, Grunewaldt KH, Løhaugen GC, Mørkved S, Skranes J, Evensen KA. Assessment of motor behaviour in high‐risk‐infants at 3 months predicts motor and cognitive outcomes in 10 years old children. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(10):787‐793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grunewaldt KH, Fjørtoft T, Bjuland KJ, et al. Follow‐up at age 10 years in ELBW children—functional outcome, brain morphology and results from motor assessments in infancy. Early Hum Dev. 2014;90(10):571‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. EXPRESS Group , Fellman V, Hellström‐Westas L, et al. One‐year survival of extremely preterm infants after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA. 2009;301:2225‐2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van Haastert IC, Groenendaal F, Uiterwaal CS, et al. Decreasing incidence and severity of cerebral palsy in prematurely born children. J Pediatr. 2011;159(1):86‐91.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kono Y, Yonemoto N, Nakanishi H, et al. Changes in survival and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants born at <25 weeks' gestation: a retrospective observational study in tertiary centres in Japan. BMJ Paediatrics Open. 2018;2:e000211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Edwards J, Berube M, Erlandson K, et al. Developmental coordination disorder in school‐aged children born very preterm and/or at very low birth weight: a systematic review. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2011;32(9):678‐687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tommiska V, Heinonen K, Ikonen S, et al. A national short‐term follow‐up study of extremely low birth weight infants born in Finland in 1996‐1997. Pediatrics. 2001;107:e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tommiska V, Heinonen K, Kero P, et al. A national 2‐year follow‐up study of extremely low birth weight infants born in 1996–1997. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003;88:F29‐F35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mikkola K, Riihela N, Tommiska V, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age of a national cohort of extremely low birth weight infants who were born in 1996–1997. Pediatrics. 2005;116:1391‐1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hutchinson EA, De Luca CR, Doyle LW, Roberts G. Anderson PJ and for the Victorian infant collaborative study group. School‐age outcomes of extremely preterm or extremely low birth weight children. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):e1053‐e1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Novak I, Morgan C, Adde L, Blackman J, Boyd RN, Brunstrom‐Hernandez J. Early, accurate diagnosis and early intervention in cerebral palsy: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):897‐907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 3rd ed. Psykologien Kustannus Oy: Helsinki, Finland; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jämsä S, Klenberg L, Lahti‐Nuuttila P, Hokkanen L. ADHD:n oireiden arviointi opettajan täyttämän kyselylomakkeen avulla [Teacher‐completed ratings of symptoms in the diagnostic evaluation of ADHD]. Psykologia. 2015;50(04):324‐341. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Henderson SE, Sugden DA. Movement Assessment Battery for Children. Kent, United Kingdom: The Psychological Corporation / Harcourt Brace Jovaninovic; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Touwen BCL. Examination of the child with minor neurological dysfunction Clinics in Developmental Medicine. London, UK: SIMP/Heinemann; 1979:71. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Serenius F, Ewald U, Farooqi A, et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely preterm infants 6.5 years after active perinatal care in Sweden. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(10):954‐963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. https://www.stat.fi/til/pop/2019/pop_2019_2019‐11‐14_tau_002_fi.html (Liitetaulukko 2. Oppivelvollisuusikäisistä muualla kuin peruskoulussa 1990–2019).

- 21. https://tilastokeskus.fi/til/erop/2013/erop_2013_2014‐06‐12_tie_001_fi.html (Erityistä tukea saaneiden osuus pieneni).

- 22. Litt JS, Taylor HG, Marcevigius S, Schluchter M, Andreias L, Hack M. Academic achievement of adolescents born with extremely low birthweight. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:1240‐1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koivisto A, Klenberg L, Tommiska V, et al. Finnish ELBW cohort study group (FinELBW). Parents tend to underestimate cognitive deficits in 10‐ to 13‐year‐olds born with an extremely low birth weight. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(11):1182‐1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stjernqvist K, Svenningsen NW. Ten‐year follow‐up of children born before 29 gestational weeks: health, cognitive development, behaviour and school achievement. Acta Paediatr. 1999;88:557‐562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yau G, Schluchter M, Taylor HG, et al. Bullying of extremely low birth weight children: associated risk factors during adolescence. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(5):333‐338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wolke D, Baumann N, Strauss V, Johnson S, Marlow N. Bullying of preterm children and emotional problems at school age: cross‐culturally invariant effects. J Pediatr. 2015;166(6):1417‐1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gianluca G, Pozzoli T. Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta‐analysis. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):720‐729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ladd GW, Ettekal I, Kochenderfer‐Ladd B. Peer victimization trajectories from kindergarten through high school: differential pathways for Children's school engagement and achievement? J Educ Psychol. 2017;109(6):826‐841. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gäddlin PO, Finnström O, Wang C, Leijon I. A fifteen‐year follow‐up of neurological conditions in VLBW children without overt disability: relation to gender, neonatal risk factors, and end stage MRI findings. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(5):343‐349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kikkert HK, De Jong C, Hadders‐Algra M. Minor neurological dysfunction and IQ in 9‐year‐old children born at term. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(4):e16‐e25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Husby IM, Skranes J, Olsen A, Brubakk AM, Evensen KA. Motor skills at 23 years of age in young adults born preterm with very low birth weight. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89(9):747‐754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Azria E, Kayem G, Langer B, et al. Neonatal mortality and long‐term outcome of infants born between 27 and 32 weeks of gestational age in breech presentation: the EPIPAGE cohort study. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guillén U, DeMauro S, Ma L, et al. Relationship between attrition and neurodevelopmental impairment rates in extremely preterm infants at 18 to 24 months. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(2):178‐184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Välijärvi J, Linnakylä P, eds. Tulevaisuuden osaajat. PISA 2000 Suomessa. Jyväskylä: Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos, OECD, and Opetushallitus; 2002. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.