Editor

The ongoing pandemic (COVID-19) effects can be seen as collateral health effects on countries' health care systems1, however, hidden aspects of management such as hospitalization period (HP) and effects on treatment facilities such as the number of hospital and critical care beds (CCBs) have not been duly acknowledged. Therefore, shortfalls of the hospitals under different scenarios like COVID-19 epidemic can be predicted. Most pandemic outcomes unfortunately start from the hospital front lines. In addition, HP is an important factor for health systems which can be effective in estimation of the required mechanical ventilators, supplies and staff1,2. Therefore, we estimated HP of COVID-19 using a systematic review and meta-analysis approach.

A registered systematic review and meta-analysis (CRD42020176951) using the PRISMA guidelines was conducted in the PubMed, Scopus and Web of science Databases. All the published peer-reviewed ducuments (Original research, short survey, and case series) on COVID-19 patients since inception till 18 April 2020, during which HP was reported or calculated (mean/median period with standard deviation (±SD) or 95 per cent CI), were included in our work. The data was quantitatively analyzed using comprehensive meta-analysis software (CMA, version 2.2.064).

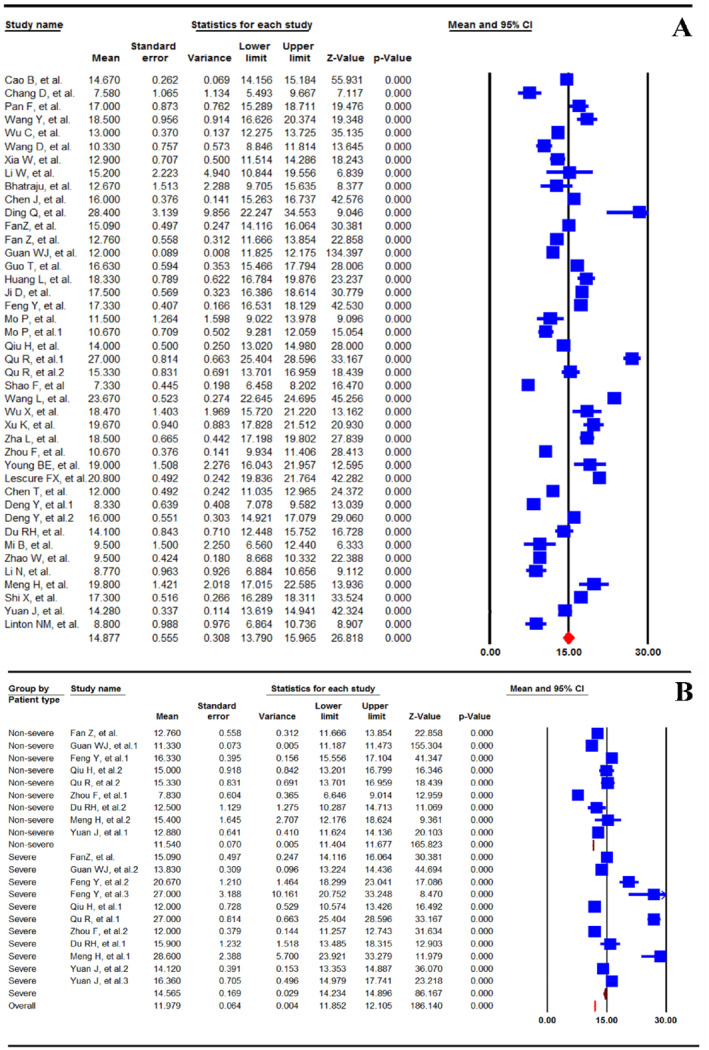

According to our results (Fig 1a), the mean Combined HP (14·88 days (95 per cent CI 13·79-15·96)) is approximately similar to that of reported for Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) (mean: 13-17 days) and longer than of Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) (median 10 days; IQR: 6-15). Although clinical features COVID-19 is not very different SARS, its own clinical parameter studied, and therefore the required treatment facilities, is almost similar to that of MERS. For this reason, and according to review of studies, the lessons learned from SARS and MERS can be based to take the efficient treatment and/or preventive measures in healthcare settings3,4. High hospitalization and case-fatality rates for COVID-19, implies on an emergence to provide sufficient hospital-based supplies. Furthermore, the mean HP was 14·56 days (95 per cent CI 14·23 to 14·90) in severe patient's categories and 11·54 days (95 per cent CI 11·40 to 11·70) in non-severe category (Fig 1b). This result is important for hospital managers and government to prepare financial and hospital resources in intensive care wards2. There is a large gap between need for hospital services and available capacity, especially for inpatient and ICU beds, which may dictate the biggest challenge in time of outbreaks due to difficulty in triaging, allocation, and shortage of both trained staff and high-level care beds2,3. This study develops the current clinical knowledge on COVID-19. Depending on the HP and disease incidence rates, governments and policy makers can consider various programs to prevention and control of this pandemic such as increase financial resources, social distancing, providing personal protective equipment, isolation and quarantine program and hospital equipment5.

Fig. 1.

Random effect model meta-analysis of hospitalization period for COVID-19 patient A) combined value (I2 = 98·18, P < 0·001); B) subgroup value: severe and non-severe (I2 = 97·89, P < 0·002). Mean values show hospitalization period in COVID-19 patients. Lower and upper limit is 95 per cent confidence intervals =95 per cent CI, I-squared: percentage of total variation across studies. For each study, areas of blue Square are proportional to weight, horizontal line shows 95 per cent CI, and red diamonds sign indicate combined effect measures. For each study, brown diamond shows mean subgroup

Supplementary Material

Appendix S1. Supporting Information

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences for their financial support (grant umber 99-01-163) for performing this research. We are willing to make our data, analytic methods, and study materials available to other researchers.

Conflict of interest statements

The authors have disclosed that they do not have any conflicts of interest.

Contributions

VKM, MS, MF and SK conceived of the manuscript; MS, TSHA, SN, MR and VKM contributed to data collection; MS, MF, and VKM contributed to data analysis and interpretation; and MS, SK, MF, TSHA, MR, VKM and SN drafted the document. All authors agree with the contents presented in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Neyshabur University of Medical Sciences, Iran, (grant umber 99-01-163).

References

- 1.COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br J Surg 2020; 10.1002/bjs.11746 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, Schnitzbauer AA, Line PD, Lai PBSet al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg 2020; 10.1002/bjs.11670 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. COVIDSurg Collaborative . Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg 2020; 107: 1097–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McBride KE, Brown KGM, Fisher OM, Steffens D, Yeo DA, Koh CE. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical services: early experiences at a nominated COVID-19 centre. ANZ J Surg 2020; 90: 663–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jessop ZM, Dobbs TD, Ali SR, Combellack E, Clancy R, Ibrahim Net al. Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) for Surgeons during COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Availability, Usage, and Rationing. Br J Surg 2020; 10.1002/bjs.11750 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supporting Information