Abstract

COVID‐19, the illness caused by SARS‐CoV‐2, has a wide‐ranging clinical spectrum that, in the worst‐case scenario, involves a rapid progression to severe acute respiratory syndrome and death. Epidemiological data show that obesity and diabetes are among the main risk factors associated with high morbidity and mortality. The increased susceptibility to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection documented in obesity‐related metabolic derangements argues for initial defects in defence mechanisms, most likely due to an elevated systemic metabolic inflammation (“metaflammation”). The NLRP3 inflammasome is a master regulator of metaflammation and has a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of either obesity or diabetes. Here, we discuss the most recent findings suggesting contribution of NLRP3 inflammasome to the increase in complications in COVID‐19 patients with diabesity. We also review current pharmacological strategies for COVID‐19, focusing on treatments whose efficacy could be due, at least in part, to interference with the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed issue on The Pharmacology of COVID‐19. To view the other articles in this section visit http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bph.v177.21/issuetoc

Keywords: COVID‐19, diabetes, inflammation, repurposing

Abbreviations

- AnxA1

annexin A1

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- BTK

Bruton's tyrosine kinase

- COVID‐19

coronavirus disease 2019

- FPR2

formyl‐peptide receptor 2

- ICU

intensive care unit

- SARS

severe acute respiratory syndrome

- SARS‐CoV‐2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TLR

toll‐like receptor

1. METAFLAMMATION IN OBESITY‐RELATED METABOLIC DISORDERS AND COVID‐19

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) is a novel member of human betacoronavirus (mutational ssRNA viruses) causing the disease named COVID‐19 (for coronavirus disease 2019), which was recognized as a pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization (WHO). COVID‐19 is a syndrome with a wide clinical spectrum. It can be asymptomatic or, in the majority of cases, cause mild symptoms that are indistinguishable from other respiratory infections, but it may also lead to a rapid progression to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), with respiratory failure and death (Zhou et al., 2020).

The activation of signalling receptors of the innate immune system is the first step of the physiological response to virus infection. However, when excessive, this innate immune system activation may evoke hyperinflammation and tissue damage in patients with severe COVID‐19, making it an important aspect of the pathophysiology of this syndrome (Netea et al., 2020).

Older people are more likely to suffer from the most serious complications of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and this susceptibility is likely to be due to the physiological decrease in the efficacy of the immune system and the simultaneous increase in age‐related inflammatory response (Latz & Duewell, 2018). Moreover, aging and the modern lifestyle typical of Western societies are both associated with an increase in co‐morbidities, such as “diabesity,” the association of obesity and diabetes, which defines a combination of primarily metabolic disorders evoked by impairment of both lipids and sugar metabolism (Potenza et al., 2017; Tschop & DiMarchi, 2012). The close relationship existing between impaired metabolism and immunity in obese‐related metabolic derangements is well documented, and the term “metaflammation” has been coined to indicate a pathophysiological inflammatory response resulting from metabolic alterations and dysfunctions (Hotamisligil, 2017; Mastrocola et al., 2018). An increasing number of studies report that patients with severe obesity or Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) exhibit an increased circulating concentration of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL‐1β, IL‐6, and TNF‐α (C. Huang et al., 2020). The metaflammation induced in response to excessive intake of calories by adipose tissue may subsequently involve other organs, such as skeletal muscle, liver, heart, and lung, leading to metabolic and cardiovascular alterations.

Compared with people of a normal weight, obese individuals have an increased susceptibility to develop chronic diseases and infections (Huttunen & Syrjanen, 2010; Milner & Beck, 2012; Wolowczuk et al., 2008). Patients with T2DM developing COVID‐19 are twice as likely to require ventilation and intensive care unit (ICU) support, and their mortality is threefold higher than in non‐diabetic COVID‐19 patients (W. J. Guan, Ni, et al., 2020; X. Yang et al., 2020). Obesity carries a fivefold increased risk of developing severe pneumonia from COVID‐19 (Cai et al., 2020), and diabesity is a well‐recognized risk factor for severe infections (Almond, Edwards, Barclay, & Johnston, 2013; Huttunen & Syrjanen, 2013), sleep apnoea (Dixon & Peters, 2018), poor immune response, and scant outcomes in patients with respiratory disease (Green & Beck, 2017). According to US data, 37% of 3,615 hospitalized COVID‐19 cases were obese, and the obesity increased the odds of ICU admission (Lighter et al., 2020). In a French study enrolling COVID‐19 patients admitted to the ICU, the requirement for ventilation was increased by sevenfold in patients with a body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2, and this was independent of age and presence of diabetes or hypertension (Simonnet et al., 2020). Direct comparison of odds ratios for the risk of SARS in obese and/or diabetic subjects, in comparison with other lung disorders, such as asthma, pulmonary hypertension, and pneumonia in the same populations, would be useful to understand the specific contribution of SARS‐CoV‐2 for both severity and prevalence of a specific organ injury. Adipocytes express high levels of ACE2, which is the receptor for SARS‐CoV‐2 (Gembardt et al., 2005; Gupte et al., 2008). Similar to infections with either human or simian immunodeficiency virus (HIV/SIV), high virus concentrations in adipose tissue may be secondary to high levels of binding cells (CD4+). Indeed, it is possible that SARS‐CoV‐2 accesses adipose tissue more easily due to the high ACE2 expression, possibly generating a viral “reservoir” in adipose tissue (Wanjalla et al., 2019). So far, most of the experimental findings have evaluated ACE2 gene expression only, whereas its parallelism with protein expression as well as enzyme functionality still needs to be confirmed to clarify the effective role of ACE2 in facilitating SARS‐CoV‐2 localization in adipose tissue.

As widely documented (Huttunen & Syrjanen, 2013; Singh, Gupta, Ghosh, & Misra, 2020), obese people and individuals with T2DM are more likely to develop a dysfunctional immune response that provokes viral infection and fails to eliminate the pathogen. Specific reasons for this are still not understood, even if one reasonable explanation could be an excessive local inflammatory response, often due to an over‐activation of specific inflammatory pathways, including, but not limited to, the NLRP3 inflammasome.

2. THE NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME AND ITS ROLE IN VIRAL INFECTION

The NLRP3 inflammasome is a large, multimeric protein complex assembled within the cell upon the recognition of unique molecular patterns by a germline‐encoded pattern recognition receptor (Y. Yang, Wang, Kouadir, Song, & Shi, 2019). Among the pattern recognition receptors known to form inflammasomes, NLRP3 belongs to the family containing both a nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain (NOD) and proteins containing a leucine‐rich repeat sequence. NLRP3 is expressed in several cell types, as innate immunity, endothelial, haematopoietic, lung epithelial, kidney, and cardiac cells (Ratajczak & Kucia, 2020). We and others have previously demonstrated that NLRP3 inflammasome over‐activation contributes to the pathogenesis of cardio‐metabolic disorders (Mastrocola, Collino, et al., 2016; O'Riordan et al., 2019; Y. Wang et al., 2020; Zuurbier et al., 2019), whereas NLRP3 deficiency results in reduced systemic inflammation, along with a decreased immune cell activation and improved insulin resistance (Grant & Dixit, 2013; Vandanmagsar et al., 2011). The NLRP3 inflammasome is also a crucial player in immune defence of the host against many pathogens, including viruses (Z. Xu et al., 2020; Zhao & Zhao, 2020). Once activated, its amino‐terminal pyrin domain is able to recruit the downstream adaptor protein apoptosis‐associated speck‐like protein containing a caspase‐recruitment domain (ASC). In addition, the amino‐terminal pyrin domain triggers the assembly of the scaffold complex important to recruit the inflammasome effector, pro‐caspase‐1, which becomes activated. Active form of caspase‐1 cleaves both pro‐IL‐1β and pro‐IL‐18 into their biologically active forms (Dinarello, 2009). Caspase‐1 can also activate an additional substrate, the gasdermin D, which mediates pyroptosis by creating pore channels in cell membranes. Pyroptosis is a lytic form of necrosis used by the innate immune system to disrupt pathogen replication and intracellular accumulation, due to the formation of pore‐induced intracellular traps (Jorgensen, Zhang, Krantz, & Miao, 2016). Despite its role in facilitating pathogen clearance, inflammasome activation can also be detrimental to the host by enhancing viral dissemination (Lupfer, Malik, & Kanneganti, 2015). To date, it is still unclear whether SARS‐CoV‐2 activates the NLRP3 inflammasome (Yap, Moriyama, & Iwasaki, 2020), but this is likely, as SARS‐CoV also activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by modulating either ion channel activity or ASC ubiquitination. Moreover, after binding to SARS‐CoV, ACE2 is internalized, leading to high cytosolic levels of angiotensin II, which is known to act as an activator of the NLRP3 inflammasome in lung, kidney cells, and cardiomyocytes (Deshotels, Xia, Sriramula, Lazartigues, & Filipeanu, 2014; S. Wang et al., 2008). In particular, activation of the ACE2/Ang(1–7) axis leads to inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasomes, associated with the down‐regulation of angiotensin II‐induced mir‐21 (Sun et al., 2017). It is possible that a similar pathway may be activated by SARS‐CoV‐2. In addition, given that caspase‐1 affects expression of several innate immunity genes and viral replication (Bauer et al., 2012), the NLRP3 inflammasome may alter cellular physiology and homeostasis also modulating gene expression, leading to altered innate antiviral defence pathways and affecting, therefore, host responsiveness to pathogens like SARS‐CoV‐2.

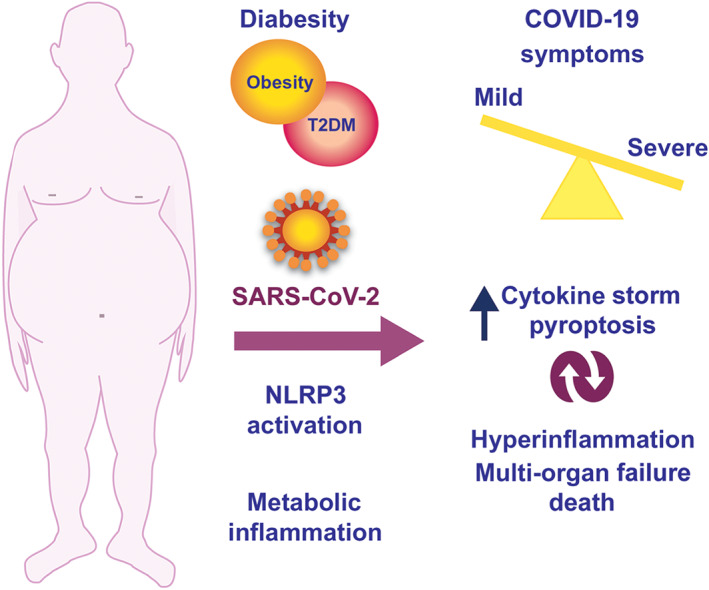

Diabesity is a high‐risk factor for both influenza infections and hospitalization for respiratory illness during seasonal influenza (Karlsson, Sheridan, & Beck, 2010; Kwong, Campitelli, & Rosella, 2011). Thus, we may speculate that the chronic over‐activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, due to metabolic impairments, may contribute to alterations in the innate immune response to viral infection, making it more permissive and severe (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The figure illustrates the relationship between diabesity—the association of obesity and diabetes—and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection response. Diabesity increases the susceptibility to exacerbation of COVID‐19 throughout an excessive metabolic inflammatory response that is regulated, at least in part, by the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. The NLRP3 inflammasome is also a master regulator of the cytokine storm and pyroptosis, both evoked by SARS‐CoV‐2 infection

3. THE NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME AND ITS INVOLVEMENT IN THE CYTOKINE STORM

The activation of both innate and adaptive immunity after recognition of viral antigens produces a large amount of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines even in moderate cases of COVID‐19. In some patients, this activation is excessive, leading to a “cytokine storm,” which in turn causes severe lung injury, multiple organ failure, and, eventually, death (Sarzi‐Puttini et al., 2020; Z. Xu et al., 2020). The mechanisms by which SARS‐CoV‐2 subverts the body's innate antiviral cytokine responses are yet to be elucidated. Nevertheless, most recent research on SARS‐CoV suggests that pyroptosis may have a pivotal role. Pyroptosis is a form of programmed cell death in a highly inflammatory state, that is commonly observed with cytopathic viruses (Fink & Cookson, 2005). As mentioned before, the NLRP3 inflammasome regulates pyroptosis by gasdermin D‐mediated membrane rupture along with spontaneous release of cytosolic contents into the extracellular spaces. The activation of pyroptosis in alveolar macrophages and in recruited monocyte‐derived macrophages by SARS‐CoV‐2 aggravates pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). The release of alarmins, including viral particles, ATP, ROS, and cytokines, chemokines, and LDH, elicits an immediate reaction from surrounding immune cells, inducing a pyroptotic chain reaction. Different studies have reported elevated levels of LDH, a cytosolic enzyme that is measured for monitoring pyroptosis (Rayamajhi, Zhang, & Miao, 2013), in patients with the severe form of the disease and worse outcomes (Lippi, Mattiuzzi, Bovo, & Plebani, 2020). In keeping with this and other observations, we can suggest the NLRP3 inflammasome‐mediated pyroptosis as one of the key mechanisms involved in COVID‐19 (Figure 1). Consequently, a further exacerbation of symptoms may derive from the pyroptosis‐induced release of viral RNA and antigens that, by reaching the circulation, may generate immune complex and depositions in other target organs, initiating severe inflammatory cascades. Hence, in addition to local damage, the cytokine storm also has ripple effects across the body, evoking organ damage and multi‐organ failure (Ruan, Yang, Wang, Jiang, & Song, 2020).

4. NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME AND RESOLUTION OF INFLAMMATION

Resolution of inflammation is an active process triggered by the onset of inflammation itself (Perretti & D'Acquisto, 2009). The main actors of this process consist of specialized pro‐resolving mediators (SPMs), whose list is constantly updated and includes annexin A1 (AnxA1), formyl‐peptide receptor 2 (FPR2), and lipoxin A4 (Brancaleone et al., 2013; Dufton et al., 2010; Norling, Dalli, Flower, Serhan, & Perretti, 2012; Serhan, Chiang, & Dalli, 2015). Very recently, AnxA1 has been reported to be involved in the regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome function (Galvao et al., 2020), independently from the binding to its cognate receptor FPR2 (Galvao et al., 2020). Indeed, lower levels of AnxA1 are associated with an increased activation of NLRP3, thus raising IL‐1β release (Kelley, Jeltema, Duan, & He, 2019). In addition, AnxA1 is also known to trigger resolution pathway by engaging FPR2 (Brancaleone et al., 2011; Machado et al., 2020; Perretti & D'Acquisto, 2009), and the AnxA1/FPR2 signalling axis has been identified to control and limit viral infection (Alessi, Cenac, Si‐Tahar, & Riteau, 2017; Lopategi et al., 2019). Therefore, impairment of this axis could unbalance the immune response to infections, thus generating an ineffective response, which in turn could lead to increased cytokine storm and exacerbation of COVID‐19 symptoms.

5. DOES NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME ACTIVATION DRIVE THE EXACERBATION OF INFLAMMATION AND DISEASE PATHOLOGY IN OBESE/DIABETIC PATIENTS WITH COVID‐19?

The specific reasons for the higher susceptibility of obese and diabetic patients to SARS‐CoV2 are unclear, but chronic exposure to a low‐grade NLRP3 inflammasome‐dependent inflammatory response may well be a key driver. Diet‐induced alterations in the gut microbiome and related increased gut leakiness of bacterial wall LPSs (endotoxins) are known to promote activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes by toll‐like receptor (TLR) pathways. This event is followed by the accumulation of IL‐1 family cytokines, which modulate the function of the insulin‐producing pancreatic beta cells (Tack, Stienstra, Joosten, & Netea, 2012). We and others have demonstrated that over‐activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome is involved not only in the pathogenesis of diabesity but also in the exacerbation of related cardiovascular injuries, including myocardial infarction, and this process is associated with an increase in the local inflammatory response. At the same time, a decrease in the efficiency of endogenous protective responses occurs (Mastrocola, Collino, et al., 2016; Y. Xu et al., 2013). NLRP3 inflammasome activation is involved in endothelial lysosome membrane permeabilization, cathepsin B release, and impaired glycocalyx thickness (Ikonomidis et al., 2019), thus further contributing to the enhanced susceptibility to cardiovascular injury. Similarly, the diabesity‐related basal activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade, leading to increase in either gastrointestinal or vascular permeability, may contribute to exacerbate SARS‐CoV‐2 systemic diffusion and enhance the intricate mechanisms of intracellular crosstalk operational in the pathogenesis of COVID‐19.

6. THE NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME AND PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENTS FOR COVID‐19

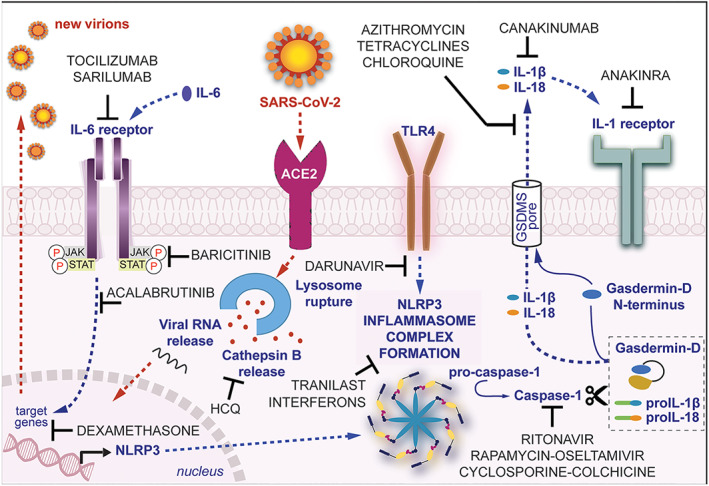

To date, there are no specific medications available to treat COVID‐19. Clinical trials are in process on several drugs, mainly based on the drug repurposing approach to redevelop a compound/drug for the use in a different disease (COVID‐19) other than that of its original use. This review summarizes recent documentations on clinically approved drugs, repurposed to counteract COVID‐19 infection, whose potential efficacy can be due, at least in part, to interference with the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade, at different levels (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

An illustration of plausible NLRP3 inflammasome‐related mechanisms targeted by clinically approved drugs, repurposed to manage COVID‐19. Following SARS‐CoV‐2 interaction with ACE2 receptors, NLRP3 inflammasome is up‐regulated to induce immune response against the virus. Overall, the over‐activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes amplifies the innate immune response and contributes to cell death by pyroptosis and virus propagation. HCQ, hydroxychloroquine

We systematically searched the PubMed and Google Scholar databases, clinicaltrials.gov, chictr.org.cn/searchprojen.aspx, and https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu until June 25, 2020, to prepare this section of the narrative review on the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in drugs repurposed in COVID‐19. We also accessed the full text of the relevant cross‐references from the search results.

6.1. Agents inhibiting activation of components of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex

To date, no specific and selective compounds which inhibit the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome are clinically available. Nonetheless, several drugs have been proposed to exert their beneficial effects, at least in part, by interfering with the activity of the NLRP3 inflammasome, although detailed mechanistic information on the mode of inhibition is lacking for many of these molecules (Mangan et al., 2018). One of the best characterized compounds used for exploring NLRP3 biology and drug ability is MCC950, which binds to NLRP3 and affects a key step in its activation (Coll et al., 2015). We recently also characterized the pharmacological profile of a newly synthesized NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, named INF4E, which directly targets the NLRP3 inflammasome and inhibits the ATPase activity of NLRP3 required for its activation (Mastrocola, Penna, et al., 2016).

6.1.1. Interferons

Among the drugs under investigation for the treatment of COVID‐19, interferons (IFNs) are those whose effects observed may be, at least in part, the result of altering activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway. Clinical trials are investigating the effects of IFNs either in combination with lopinavir/ritonavir (Chinese Clinical Trial Registry identifier: ChiCTR2000029387) or lopinavir/ritonavir/ribavirin (NCT04276688 and EudraCT database identifier: 2020‐001023‐14).

Selective interactions between type‐I IFNs and NLRP3 inflammasomes have been documented. For instance, both type‐I IFNs and IFN‐γ evoke higher expression of inducible NOS, increasing levels of endogenous NO, which inhibits NLRP3 oligomerization by means of direct S‐nitrosylation of the NLRP3 protein, avoiding full inflammasome organization (Mishra et al., 2013). Another mechanism resides in the ability of type‐I IFN to decrease the NLRP3 inflammasome activation via the transcription factor STAT1, that induces caspase‐1 to process the IL‐1β precursor (Kopitar‐Jerala, 2017).

6.1.2. Antiviral agents

The administration of the protease inhibitor ritonavir in association with lopinavir has been tested for the treatment of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19 pneumonia (Cao et al., 2020), and there are several ongoing clinical trials in China (NCT04255017, NCT04261907, NCT04286503, and NCT04295551), Hong Kong (NCT04276688), Republic of Korea (NCT04307693), and Europe (NCT04315948 and NCT04328285). The protease inhibitor darunavir is under investigation as an alternative drug to lopinavir/ritonavir treatment in COVID‐19 (NCT04252274 and ChiCTR2000029541). Other two clinical trials (NCT04261270 and NCT04303299) have been proposed to evaluate oseltamivir, a neuraminidase inhibitor approved for the treatment of influenza, alone or in combination with ritonavir or favipiravir, darunavir, and chloroquine. Interestingly, the three antiviral drugs here mentioned interfere with NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Ritonavir has been demonstrated to inhibit caspase‐1 activation leading to reduced cleavage of pro‐IL‐18 (Weichold et al., 1999), whereas darunavir limits the expression of key regulators of NLRP3 inflammasome complex formation, TLR4 and NF‐κB (Zhang et al., 2018). In contrast, oseltamivir had no effect on the expression of NLRP3 and IL‐1β, however, when administered in combination with sirolimus, it drastically improves the ability of sirolimus to repress NLRP3 inflammasome activation and NLRP3 inflammasome‐mediated secretion of IL‐1β in lung epithelial cells infected with influenza virus (Jia et al., 2018).

6.1.3. Azithromycin

Few clinical trials are recruiting patients with COVID‐19 to test the efficacy of the known macrolide antibiotic azithromycin alone (NCT04332107, NCT04381962, NCT04369365, and NCT04371107) or in combination with hydroxychloroquine (NCT04339816 and NCT04336332).

The beneficial effects of azithromycin against LPS‐induced pulmonary neutrophilia have been documented to involve NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition (Bosnar et al., 2011; Gualdoni et al., 2015), which is also involved in mediating tetracycline beneficial effects in experimental models of diabetic retinopathy and ischaemic stroke (W. Chen, Zhao, et al., 2017; Lu, Xiao, & Luo, 2016).

6.1.4. Immunosuppressants

Three clinical trials are recruiting COVID‐19 patients to test the efficacy of the immunosuppressant sirolimus (NCT04341675, NCT04371640, and NCT04374903), whereas no clinical study on the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine in COVID‐19 has been recorded, although it has been suggested as a potential treatment for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (Cure, Kucuk, & Cumhur Cure, 2020). Both these immunosuppressants can interfere with NLRP3 inflammasome. Sirolimus inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages through autophagy induction (Ko, Yoon, Lee, & Oh, 2017), whereas cyclosporine targets cyclophilin D to prevent the opening of the mitochondria permeability transition pore, which is involved in NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Iyer et al., 2013).

Another well‐known NLRP3 inhibitor included in several clinical protocols for COVID‐19 patients is the classical anti‐mitotic drug colchicine, with at least 10 ongoing clinical trials (NCT04328480, NCT04322682, 2020‐001841‐38, NCT04392141, 2020‐001511‐25, NCT04322565, NCT04375202, NCT04360980, 2020‐001603‐16, and NCT04363437) and 3 others ready to start (NCT04367168, NCT04355143, and NCT04326790). Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how colchicine can suppress NLRP3 inflammasome activation. First, colchicine can inhibit the expression of pyrin gene, preventing the assembly of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex (Nidorf, Eikelboom, & Thompson, 2014). Second, colchicine inhibits activation of caspase‐1 and mature IL‐1β (Otani et al., 2016). Third, colchicine inhibits P2X7 receptor‐induced pore formation, a key step in NLRP3 inflammasome activation following ATP exposure (Marques‐da‐Silva, Chaves, Castro, Coutinho‐Silva, & Guimaraes, 2011).

6.1.5. Tranilast

Tranilast, an analogue of a tryptophan metabolite, which has been used in allergic disorders such as bronchial asthma, has been recently suggested for repurposing in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia (ChiCTR2000030002). As convincingly demonstrated (Y. Huang et al., 2018), tranilast targets NLRP3 or NLRP3–ASC interaction to block the assembly of NLRP3 inflammasome, thus exerting significant beneficial effects in experimental models of inflammation‐associated diseases.

6.2. Agents inhibiting expression of components of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex

Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation can be achieved by limiting the expression of the main component of the inflammasome complex, although this approach is not specific and is likely to produce many off‐target effects.

6.2.1. JAK and Bruton's TK inhibitors

Low MW compounds with immunomodulatory properties, already proposed for COVID‐19 infection and with documented modulatory activity on expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components, are the JAK inhibitor baricitinib and the Bruton's TK (BTK) inhibitor acalabrutinib. A study on baricitinib has already been concluded with interesting results (NCT04358614), and others are recruiting patients for both the treatments (baricitinib: NCT04320277 and NCT04390464; acalabrutinib: NCT04346199 and NCT04380688). Experimental evidence for key roles of the JAK and BTK cascades in modulating expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome and diabesity pathogenesis has been published (Collotta et al., 2020; Furuya et al., 2018; Purvis et al., 2020).

Up to now, six clinical trials (NCT04347980, NCT04325061, NCT04395105, NCT04344730, NCT04360876, and NCT04327401) reported on clinicaltrials.gov are recruiting patients to test the efficacy of the corticosteroid dexamethasone, whose beneficial effects in airway inflammation have been recently demonstrated to involve lung inhibition of the activity of NLRP3 inflammasome and the release of IL‐1β and IL‐18 (M. Guan, Ma, et al., 2020).

6.2.2. Antimalarial agents

Chloroquine and its analogue hydroxychloroquine, two well‐known antimalarial drugs, have been proposed for severe COVID‐19 treatment, with more than 70 clinical trials registered on clinicaltrials.gov. Several studies have demonstrated the anti‐inflammatory activity of chloroquine mainly due to significant inhibition of cytokine release, including IL‐1β, from monocytes and macrophages (Hong et al., 2004). Recently, a direct role for chloroquine in inhibiting the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome components has been demonstrated (X. Chen, Wang, et al., 2017). Besides, hydroxychloroquine exerts its anti‐inflammatory effect by inhibiting cathepsin‐mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation (Tang et al., 2018). As recently reported (Lucchesi et al., 2020), the pleiotropic effects of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine on NLRP3 inflammasome expression and activation may significantly contribute to the ability of these antimalarial drugs to accelerate the recovery of patients with SARS‐CoV‐2‐induced ARDS.

6.3. Agents inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome‐mediated effector mechanisms

Blocking downstream signalling molecules, such as IL‐1β, may provide a means to regulate NLRP3 inflammasome activation. However, the efficacy of this approach is limited because NLRP3 induces a variety of pro‐inflammatory mediators in addition to IL‐1β, and conversely, the risk of immune suppression would be higher because IL‐1β is produced by a variety of non‐NLRP3 inflammasome‐dependent pathways in response to a variety of stimuli.

6.3.1. Anti‐IL‐1 agents

There are at least eight clinical trials on pharmacological strategies specifically aimed to target the main product of NLRP3 inflammasome activation, the cytokine IL‐1β. They include studies on the human anti‐IL‐1β monoclonal antibody canakinumab (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT04362813, NCT04365153, and NCT04348448) and the recombinant non‐glycosylated human IL‐1 receptor antagonist anakinra (NCT04324021, NCT04330638, NCT0432402, NCT04357366, and NCT04339712). Besides, several other clinical trials are evaluating the effects of drugs targeting IL‐6, whose serum concentrations are drastically increased in patients with NLRP3 inflammasome‐mediated condition (Abbate et al., 2020). A crosstalk mechanism linking IL‐1β to IL‐6 has been documented. IL‐1β induces IL‐6 gene transcription via a PI3K / Akt‐dependent pathways (Cahill & Rogers, 2008), and, at the same time, blockade of IL‐6 signalling blunts the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome (Powell et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2018). Thus, drugs able to interfere with IL‐6 receptor activation may inhibit NLRP3‐dependent IL‐1β release, and, in a similar way, anti‐IL‐1β strategies significantly reduce IL‐6 release, with an effective control of the cytokine storm. Several clinical trials have been approved to test the efficacy of sarilumab (NCT04315298 and NCT04327388, EudraCT identifier: 2020‐001162‐12 and 2020‐001390‐76) and tocilizumab (ChinaXiv identifier: 202003.00026 and 20000.30894), two humanized monoclonal antibodies against the IL‐6 receptor, thus confirming that targeting cellular machineries leading to cytokine overproduction, such as the NLRP3 inflammasome, holds promise for COVID‐19 therapy.

7. CONCLUSIONS

Both infection and individual dysfunctional immune response elicited by SARS‐CoV‐2 have been reported to contribute to COVID‐19 pathogenesis. Thus, it is more than a speculation that controlling the inflammatory response may be as important as targeting the virus. The evidence here reported suggest a potential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome pathway as a crosstalk mechanism involved in both cellular events. Indeed, pharmacological targeting of NLRP3 inflammasome could be a feasible approach to counteract the pathology at multiple levels, ranging from the interference with viral infection to the reassessment of unbalanced immune responses. In addition, patients with exacerbated disease might reveal an impaired resolution process, which could again reflect on NLRP3 hyper‐activation contributing to the “cytokine storm.” Interestingly, some of the pharmacological strategies under investigation for COVID‐19 therapy include drugs able to directly disrupt the NLRP3 inflammasome cascade or to affect the transcriptional activity of factors involved in the synthesis of the main components of the NLRP3 inflammasome complex. Further studies are needed to better elucidate the pathophysiological involvement of NLRP3 inflammasome in this specific context and to prove the efficacy and safety of related pharmacological strategies. Overall, the findings here reviewed underlie intriguing perspectives within the intricate mechanisms involved in the COVID‐19 pathogenesis, and, thus, they may contribute to raise hope for discovering new strategies to battle one of the major pandemics of our modern times.

7.1. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (http://www.guidetopharmacology.org) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 (Alexander, Christopoulos et al., 2019; Alexander, Fabbro et al., 2019a, b; Alexander, Kelly et al., 2019; Alexander, Mathie et al., 2019).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Bertocchi I, Foglietta F, Collotta D, et al. The hidden role of NLRP3 inflammasome in obesity‐related COVID‐19 exacerbations: Lessons for drug repurposing. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177:4921–4930. 10.1111/bph.15229

REFERENCES

- Abbate, A. , Toldo, S. , Marchetti, C. , Kron, J. , Van Tassell, B. W. , & Dinarello, C. A. (2020). Interleukin‐1 and the inflammasome as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular disease. Circulation Research, 126, 1260–1280. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.315937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi, M. C. , Cenac, N. , Si‐Tahar, M. , & Riteau, B. (2017). FPR2: A novel promising target for the treatment of influenza. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, 1719 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Christopoulos, A. , Davenport, A. P. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , … CGTP Collaborators . (2019). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein‐coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S21–S141. 10.1111/bph.14748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , … CGTP Collaborators . (2019a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Catalytic receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S247–S296. 10.1111/bph.14751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Fabbro, D. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , … CGTP Collaborators . (2019b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Enzymes. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S297–S396. 10.1111/bph.14752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Kelly, E. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , Faccenda, E. , … CGTP Collaborators . (2019). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Other Protein Targets. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S1–S20. 10.1111/bph.14747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, S. P. H. , Mathie, A. , Peters, J. A. , Veale, E. L. , Striessnig, J. , Kelly, E. , … CGTP Collaborators . (2019). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: Ion channels. British Journal of Pharmacology, 176, S142–S228. 10.1111/bph.14749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond, M. H. , Edwards, M. R. , Barclay, W. S. , & Johnston, S. L. (2013). Obesity and susceptibility to severe outcomes following respiratory viral infection. Thorax, 68, 684–686. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R. N. , Brighton, L. E. , Mueller, L. , Xiang, Z. , Rager, J. E. , Fry, R. C. , … Jaspers, I. (2012). Influenza enhances caspase‐1 in bronchial epithelial cells from asthmatic volunteers and is associated with pathogenesis. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 130(958–967), e914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosnar, M. , Cuzic, S. , Bosnjak, B. , Nujic, K. , Ergovic, G. , Marjanovic, N. , … Haber, V. E. (2011). Azithromycin inhibits macrophage interleukin‐1β production through inhibition of activator protein‐1 in lipopolysaccharide‐induced murine pulmonary neutrophilia. International Immunopharmacology, 11, 424–434. 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaleone, V. , Dalli, J. , Bena, S. , Flower, R. J. , Cirino, G. , & Perretti, M. (2011). Evidence for an anti‐inflammatory loop centered on polymorphonuclear leukocyte formyl peptide receptor 2/lipoxin A4 receptor and operative in the inflamed microvasculature. Journal of Immunology, 186, 4905–4914. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaleone, V. , Gobbetti, T. , Cenac, N. , le Faouder, P. , Colom, B. , Flower, R. J. , … Perretti, M. (2013). A vasculo‐protective circuit centered on lipoxin A4 and aspirin‐triggered 15‐epi‐lipoxin A4 operative in murine microcirculation. Blood, 122, 608–617. 10.1182/blood-2013-04-496661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, C. M. , & Rogers, J. T. (2008). Interleukin (IL) 1β induction of IL‐6 is mediated by a novel phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase‐dependent AKT/IκB kinase α pathway targeting activator protein‐1. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283, 25900–25912. 10.1074/jbc.M707692200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Q. , Chen, F. , Wang, T. , Luo, F. , Liu, X. , Wu, Q. , … Xu, L. (2020). Obesity and COVID‐19 severity in a designated hospital in Shenzhen, China. Diabetes Care, 43, 1392–1398. 10.2337/dc20-0576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, B. , Wang, Y. , Wen, D. , Liu, W. , Wang, J. , Fan, G. , … Wang, C. (2020). A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid‐19. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1787–1799. 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W. , Zhao, M. , Zhao, S. , Lu, Q. , Ni, L. , Zou, C. , … Qiu, Q. (2017). Activation of the TXNIP/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway contributes to inflammation in diabetic retinopathy: A novel inhibitory effect of minocycline. Inflammation Research, 66, 157–166. 10.1007/s00011-016-1002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Wang, N. , Zhu, Y. , Lu, Y. , Liu, X. , & Zheng, J. (2017). The antimalarial chloroquine suppresses LPS‐induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation and confers protection against murine endotoxic shock. Mediators of Inflammation, 2017, 6543237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coll, R. C. , Robertson, A. A. , Chae, J. J. , Higgins, S. C. , Muñoz‐Planillo, R. , Inserra, M. C. , … Croker, D. E. (2015). A small‐molecule inhibitor of the NLRP3 inflammasome for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. Nature Medicine, 21, 248–255. 10.1038/nm.3806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collotta, D. , Hull, W. , Mastrocola, R. , Chiazza, F. , Cento, A. S. , Murphy, C. , … Thiemermann, C. (2020). Baricitinib counteracts metaflammation, thus protecting against diet‐induced metabolic abnormalities in mice. Mol Metab, 39, 101009 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.101009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cure, E. , Kucuk, A. , & Cumhur Cure, M. (2020). Cyclosporine therapy in cytokine storm due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Rheumatology International, 40, 1177–1179. 10.1007/s00296-020-04603-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshotels, M. R. , Xia, H. , Sriramula, S. , Lazartigues, E. , & Filipeanu, C. M. (2014). Angiotensin II mediates angiotensin converting enzyme type 2 internalization and degradation through an angiotensin II type I receptor‐dependent mechanism. Hypertension, 64, 1368–1375. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello, C. A. (2009). Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin‐1 family. Annual Review of Immunology, 27, 519–550. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, A. E. , & Peters, U. (2018). The effect of obesity on lung function. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine, 12, 755–767. 10.1080/17476348.2018.1506331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufton, N. , Hannon, R. , Brancaleone, V. , Dalli, J. , Patel, H. B. , Gray, M. , … Flower, R. J. (2010). Anti‐inflammatory role of the murine formyl‐peptide receptor 2: Ligand‐specific effects on leukocyte responses and experimental inflammation. Journal of Immunology, 184, 2611–2619. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink, S. L. , & Cookson, B. T. (2005). Apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necrosis: Mechanistic description of dead and dying eukaryotic cells. Infection and Immunity, 73, 1907–1916. 10.1128/IAI.73.4.1907-1916.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuya, M. Y. , Asano, T. , Sumichika, Y. , Sato, S. , Kobayashi, H. , Watanabe, H. , … Migita, K. (2018). Tofacitinib inhibits granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor‐induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation in human neutrophils. Arthritis Research & Therapy, 20, 196 10.1186/s13075-018-1685-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvao, I. , de Carvalho, R. V. H. , Vago, J. P. , Silva, A. L. N. , Carvalho, T. G. , Antunes, M. M. , … Teixeira, M. M. (2020). The role of annexin A1 in the modulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunology, 160, 78–89. 10.1111/imm.13184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gembardt, F. , Sterner‐Kock, A. , Imboden, H. , Spalteholz, M. , Reibitz, F. , Schultheiss, H. P. , … Walther, T. (2005). Organ‐specific distribution of ACE2 mRNA and correlating peptidase activity in rodents. Peptides, 26, 1270–1277. 10.1016/j.peptides.2005.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, R. W. , & Dixit, V. D. (2013). Mechanisms of disease: Inflammasome activation and the development of type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Immunology, 4, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, W. D. , & Beck, M. A. (2017). Obesity impairs the adaptive immune response to influenza virus. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 14, S406–S409. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201706-447AW [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualdoni, G. A. , Lingscheid, T. , Schmetterer, K. G. , Hennig, A. , Steinberger, P. , & Zlabinger, G. J. (2015). Azithromycin inhibits IL‐1 secretion and non‐canonical inflammasome activation. Scientific Reports, 5, 12016 10.1038/srep12016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, M. , Ma, H. , Fan, X. , Chen, X. , Miao, M. , & Wu, H. (2020). Dexamethasone alleviate allergic airway inflammation in mice by inhibiting the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. International Immunopharmacology, 78, 106017 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.106017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, W. J. , Ni, Z. Y. , Hu, Y. , Liang, W. H. , Ou, C. Q. , He, J. X. , … China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid‐19 . (2020). Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1708–1720. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupte, M. , Boustany‐Kari, C. M. , Bharadwaj, K. , Police, S. , Thatcher, S. , Gong, M. C. , … Cassis, L. A. (2008). ACE2 is expressed in mouse adipocytes and regulated by a high‐fat diet. American Journal of Physiology Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 295, R781–R788. 10.1152/ajpregu.00183.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z. , Jiang, Z. , Liangxi, W. , Guofu, D. , Ping, L. , Yongling, L. , … Minghai, W. (2004). Chloroquine protects mice from challenge with CpG ODN and LPS by decreasing proinflammatory cytokine release. International Immunopharmacology, 4, 223–234. 10.1016/j.intimp.2003.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil, G. S. (2017). Inflammation, metaflammation and immunometabolic disorders. Nature, 542, 177–185. 10.1038/nature21363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. , Wang, Y. , Li, X. , Ren, L. , Zhao, J. , Hu, Y. , … Cao, B. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet, 395, 497–506. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. , Jiang, H. , Chen, Y. , Wang, X. , Yang, Y. , Tao, J. , … Zhou, R. (2018). Tranilast directly targets NLRP3 to treat inflammasome‐driven diseases. EMBO Molecular Medicine, 10 10.15252/emmm.201708689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen, R. , & Syrjanen, J. (2010). Obesity and the outcome of infection. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 10, 442–443. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70103-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen, R. , & Syrjanen, J. (2013). Obesity and the risk and outcome of infection. International Journal of Obesity, 37, 333–340. 10.1038/ijo.2012.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikonomidis, I. , Pavlidis, G. , Katsimbri, P. , Andreadou, I. , Triantafyllidi, H. , Tsoumani, M. , … Iliodromitis, E. (2019). Differential effects of inhibition of interleukin 1 and 6 on myocardial, coronary and vascular function. Clinical Research in Cardiology, 108, 1093–1101. 10.1007/s00392-019-01443-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer, S. S. , He, Q. , Janczy, J. R. , Elliott, E. I. , Zhong, Z. , Olivier, A. K. , … Sutterwala, F. S. (2013). Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity, 39, 311–323. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X. , Liu, B. , Bao, L. , Lv, Q. , Li, F. , Li, H. , … Wang, C. (2018). Delayed oseltamivir plus sirolimus treatment attenuates H1N1 virus‐induced severe lung injury correlated with repressed NLRP3 inflammasome activation and inflammatory cell infiltration. PLoS Pathogens, 14, e1007428 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen, I. , Zhang, Y. , Krantz, B. A. , & Miao, E. A. (2016). Pyroptosis triggers pore‐induced intracellular traps (PITs) that capture bacteria and lead to their clearance by efferocytosis. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 213, 2113–2128. 10.1084/jem.20151613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson, E. A. , Sheridan, P. A. , & Beck, M. A. (2010). Diet‐induced obesity impairs the T cell memory response to influenza virus infection. Journal of Immunology, 184, 3127–3133. 10.4049/jimmunol.0903220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, N. , Jeltema, D. , Duan, Y. , & He, Y. (2019). The NLRP3 inflammasome: An overview of mechanisms of activation and regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20 10.3390/ijms20133328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko, J. H. , Yoon, S. O. , Lee, H. J. , & Oh, J. Y. (2017). Rapamycin regulates macrophage activation by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome‐p38 MAPK‐NFκB pathways in autophagy‐ and p62‐dependent manners. Oncotarget, 8, 40817–40831. 10.18632/oncotarget.17256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopitar‐Jerala, N. (2017). The role of interferons in inflammation and inflammasome activation. Frontiers in Immunology, 8, 873 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong, J. C. , Campitelli, M. A. , & Rosella, L. C. (2011). Obesity and respiratory hospitalizations during influenza seasons in Ontario, Canada: A cohort study. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 53, 413–421. 10.1093/cid/cir442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latz, E. , & Duewell, P. (2018). NLRP3 inflammasome activation in inflammaging. Seminars in Immunology, 40, 61–73. 10.1016/j.smim.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lighter, J. , Phillips, M. , Hochman, S. , Sterling, S. , Johnson, D. , Francois, F. , & Stachel, A. (2020). Obesity in patients younger than 60 years is a risk factor for Covid‐19 hospital admission. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 71, 896–897. 10.1093/cid/ciaa415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi, G. , Mattiuzzi, C. , Bovo, C. , & Plebani, M. (2020). Current laboratory diagnostics of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Acta Biomed, 91, 137–145. 10.23750/abm.v91i2.9548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopategi, A. , Flores‐Costa, R. , Rius, B. , Lopez‐Vicario, C. , Alcaraz‐Quiles, J. , Titos, E. , & Clària, J. (2019). Frontline Science: Specialized proresolving lipid mediators inhibit the priming and activation of the macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome. Journal of Leukocyte Biology, 105, 25–36. 10.1002/JLB.3HI0517-206RR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y. , Xiao, G. , & Luo, W. (2016). Minocycline suppresses NLRP3 inflammasome activation in experimental ischemic stroke. Neuroimmunomodulation, 23, 230–238. 10.1159/000452172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchesi, A. , Silimbani, P. , Musuraca, G. , Cerchione, C. , Martinelli, G. , Di Carlo, P. , & Napolitano, M. (2020). Clinical and biological data on the use of hydroxychloroquine against SARS‐CoV‐2 could support the role of the NLRP3 inflammasome in the pathogenesis of respiratory disease. Journal of Medical Virology.. 10.1002/jmv.26217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupfer, C. , Malik, A. , & Kanneganti, T. D. (2015). Inflammasome control of viral infection. Current Opinion in Virology, 12, 38–46. 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, M. G. , Tavares, L. P. , Souza, G. V. S. , Queiroz‐Junior, C. M. , Ascencao, F. R. , Lopes, M. E. , … Teixeira, M. M. (2020). The Annexin A1/FPR2 pathway controls the inflammatory response and bacterial dissemination in experimental pneumococcal pneumonia. The FASEB Journal, 34, 2749–2764. 10.1096/fj.201902172R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangan, M. S. J. , Olhava, E. J. , Roush, W. R. , Seidel, H. M. , Glick, G. D. , & Latz, E. (2018). Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 17, 688 10.1038/nrd.2018.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques‐da‐Silva, C. , Chaves, M. M. , Castro, N. G. , Coutinho‐Silva, R. , & Guimaraes, M. Z. (2011). Colchicine inhibits cationic dye uptake induced by ATP in P2X2 and P2X7 receptor‐expressing cells: Implications for its therapeutic action. British Journal of Pharmacology, 163, 912–926. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01254.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrocola, R. , Aragno, M. , Alloatti, G. , Collino, M. , Penna, C. , & Pagliaro, P. (2018). Metaflammation: Tissue‐specific alterations of the NLRP3 inflammasome platform in metabolic syndrome. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 25, 1294–1310. 10.2174/0929867324666170407123522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrocola, R. , Collino, M. , Penna, C. , Nigro, D. , Chiazza, F. , Fracasso, V. , … Aragno, M. (2016). Maladaptive modulations of NLRP3 inflammasome and cardioprotective pathways are involved in diet‐induced exacerbation of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016, 3480637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrocola, R. , Penna, C. , Tullio, F. , Femminò, S. , Nigro, D. , Chiazza, F. , … Bertinaria, M. (2016). Pharmacological inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by activation of RISK and mitochondrial pathways. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016, 5271251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner, J. J. , & Beck, M. A. (2012). The impact of obesity on the immune response to infection. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 71, 298–306. 10.1017/S0029665112000158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, B. B. , Rathinam, V. A. , Martens, G. W. , Martinot, A. J. , Kornfeld, H. , Fitzgerald, K. A. , & Sassetti, C. M. (2013). Nitric oxide controls the immunopathology of tuberculosis by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome‐dependent processing of IL‐1β. Nature Immunology, 14, 52–60. 10.1038/ni.2474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netea, M. G. , Giamarellos‐Bourboulis, E. J. , Dominguez‐Andres, J. , Curtis, N. , van Crevel, R. , van de Veerdonk, F. L. , & Bonten, M. (2020). Trained immunity: A tool for reducing susceptibility to and the severity of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Cell, 181, 969–977. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nidorf, S. M. , Eikelboom, J. W. , & Thompson, P. L. (2014). Targeting cholesterol crystal‐induced inflammation for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 19, 45–52. 10.1177/1074248413499972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norling, L. V. , Dalli, J. , Flower, R. J. , Serhan, C. N. , & Perretti, M. (2012). Resolvin D1 limits polymorphonuclear leukocyte recruitment to inflammatory loci: Receptor‐dependent actions. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 32, 1970–1978. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.249508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Riordan, C. E. , Purvis, G. S. D. , Collotta, D. , Chiazza, F. , Wissuwa, B. , Al Zoubi, S. , … Thiemermann, C. (2019). Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibition attenuates the cardiac dysfunction caused by cecal ligation and puncture in mice. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 2129 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Otani, K. , Watanabe, T. , Shimada, S. , Takeda, S. , Itani, S. , Higashimori, A. , … Arakawa, T. (2016). Colchicine prevents NSAID‐induced small intestinal injury by inhibiting activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Scientific Reports, 6, 32587 10.1038/srep32587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perretti, M. , & D'Acquisto, F. (2009). Annexin A1 and glucocorticoids as effectors of the resolution of inflammation. Nature Reviews. Immunology, 9, 62–70. 10.1038/nri2470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza, M. A. , Nacci, C. , De Salvia, M. A. , Sgarra, L. , Collino, M. , & Montagnani, M. (2017). Targeting endothelial metaflammation to counteract diabesity cardiovascular risk: Current and perspective therapeutic options. Pharmacological Research, 120, 226–241. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell, N. , Lo, J. W. , Biancheri, P. , Vossenkamper, A. , Pantazi, E. , Walker, A. W. , … Canavan, J. B. (2015). Interleukin 6 increases production of cytokines by colonic innate lymphoid cells in mice and patients with chronic intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology, 149(456–467), e415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, G. S. D. , Collino, M. , Aranda‐Tavio, H. , Chiazza, F. , O'Riordan, C. E. , Zeboudj, L. , … Thiemermann, C. (2020). Inhibition of Bruton's tyrosine kinase regulates macrophage NF‐κB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in metabolic inflammation. British Journal of Pharmacology. 10.1111/bph.15182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak, M. Z. , & Kucia, M. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and overactivation of Nlrp3 inflammasome as a trigger of cytokine “storm” and risk factor for damage of hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia, 34, 1726–1729. 10.1038/s41375-020-0887-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayamajhi, M. , Zhang, Y. , & Miao, E. A. (2013). Detection of pyroptosis by measuring released lactate dehydrogenase activity. Methods in Molecular Biology, 1040, 85–90. 10.1007/978-1-62703-523-1_7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Q. , Yang, K. , Wang, W. , Jiang, L. , & Song, J. (2020). Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID‐19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Medicine, 46(5), 846–848. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarzi‐Puttini, P. , Giorgi, V. , Sirotti, S. , Marotto, D. , Ardizzone, S. , Rizzardini, G. , … Galli, M. (2020). COVID‐19, cytokines and immunosuppression: What can we learn from severe acute respiratory syndrome? Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 38, 337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan, C. N. , Chiang, N. , & Dalli, J. (2015). The resolution code of acute inflammation: Novel pro‐resolving lipid mediators in resolution. Seminars in Immunology, 27, 200–215. 10.1016/j.smim.2015.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonnet, A. , Chetboun, M. , Poissy, J. , Raverdy, V. , Noulette, J. , Duhamel, A. , … LICORN and the Lille COVID‐19 and Obesity study group . (2020). Lille Intensive Care COVID‐19 and Obesity study group. High prevalence of obesity in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus‐2 (SARS‐CoV‐2) requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. Obesity (Silver Spring). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A. K. , Gupta, R. , Ghosh, A. , & Misra, A. (2020). Diabetes in COVID‐19: Prevalence, pathophysiology, prognosis and practical considerations. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research and Reviews, 14, 303–310. 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N. N. , Yu, C. H. , Pan, M. X. , Zhang, Y. , Zheng, B. J. , Yang, Q. J. , … Meng, Y. (2017). Mir‐21 mediates the inhibitory effect of Ang(1–7) on AngII‐induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation by targeting Spry1 in lung fibroblasts. Scientific Reports, 7, 14369 10.1038/s41598-017-13305-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tack, C. J. , Stienstra, R. , Joosten, L. A. , & Netea, M. G. (2012). Inflammation links excess fat to insulin resistance: The role of the interleukin‐1 family. Immunological Reviews, 249, 239–252. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01145.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, T. T. , Lv, L. L. , Pan, M. M. , Wen, Y. , Wang, B. , Li, Z. L. , … Liu, B. C. (2018). Hydroxychloroquine attenuates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting cathepsin mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Death & Disease, 9, 351 10.1038/s41419-018-0378-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschop, M. H. , & DiMarchi, R. D. (2012). Outstanding Scientific Achievement Award Lecture 2011: Defeating diabesity: The case for personalized combinatorial therapies. Diabetes, 61, 1309–1314. 10.2337/db12-0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandanmagsar, B. , Youm, Y. H. , Ravussin, A. , Galgani, J. E. , Stadler, K. , Mynatt, R. L. , … Dixit, V. D. (2011). The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity‐induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nature Medicine, 17, 179–188. 10.1038/nm.2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S. , Guo, F. , Liu, K. , Wang, H. , Rao, S. , Yang, P. , & Jiang, C. (2008). Endocytosis of the receptor‐binding domain of SARS‐CoV spike protein together with virus receptor ACE2. Virus Research, 136, 8–15. 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. , Liu, X. , Shi, H. , Yu, Y. , Yu, Y. , Li, M. , & Chen, R. (2020). NLRP3 inflammasome, an immune‐inflammatory target in pathogenesis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Clinical and Translational Medicine, 10, 91–106. 10.1002/ctm2.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanjalla, C. N. , McDonnell, W. J. , Barnett, L. , Simmons, J. D. , Furch, B. D. , Lima, M. C. , … Ram, R. (2019). Adipose tissue in persons with HIV is enriched for CD4+ T effector memory and T effector memory RA+ cells, which show higher CD69 expression and CD57, CX3CR1, GPR56 co‐expression with increasing glucose intolerance. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 408 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichold, F. F. , Bryant, J. L. , Pati, S. , Barabitskaya, O. , Gallo, R. C. , & Reitz, M. S. Jr. (1999). HIV‐1 protease inhibitor ritonavir modulates susceptibility to apoptosis of uninfected T cells. Journal of Human Virology, 2, 261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolowczuk, I. , Verwaerde, C. , Viltart, O. , Delanoye, A. , Delacre, M. , Pot, B. , & Grangette, C. (2008). Feeding our immune system: Impact on metabolism. Clinical & Developmental Immunology, 2008, 639803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R. , Liu, X. , Yin, J. , Wu, H. , Cai, X. , Wang, N. , … Wang, F. (2018). IL‐6 receptor blockade ameliorates diabetic nephropathy via inhibiting inflammasome in mice. Metabolism, 83, 18–24. 10.1016/j.metabol.2018.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y. , Ma, L. L. , Zhou, C. , Zhang, F. J. , Kong, F. J. , Wang, W. N. , … Wang, J. A. (2013). Hypercholesterolemic myocardium is vulnerable to ischemia‐reperfusion injury and refractory to sevoflurane‐induced protection. PLoS ONE, 8, e76652 10.1371/journal.pone.0076652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. , Shi, L. , Wang, Y. , Zhang, J. , Huang, L. , Zhang, C. , … Wang, F. S. (2020). Pathological findings of COVID‐19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8, 420–422. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. , Yu, Y. , Xu, J. , Shu, H. , Xia, J. , Liu, H. , … Wang, Y. (2020). Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single‐centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8, 475–481. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y. , Wang, H. , Kouadir, M. , Song, H. , & Shi, F. (2019). Recent advances in the mechanisms of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and its inhibitors. Cell Death & Disease, 10, 128 10.1038/s41419-019-1413-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap, J. K. Y. , Moriyama, M. , & Iwasaki, A. (2020). Inflammasomes and pyroptosis as therapeutic targets for COVID‐19. Journal of Immunology, 205, 307–312. 10.4049/jimmunol.2000513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. , Zhang, G. , Ren, Y. , Lan, T. , Li, D. , Tian, J. , & Jiang, W. (2018). Darunavir alleviates irinotecan‐induced intestinal toxicity in vivo . European Journal of Pharmacology, 834, 288–294. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, C. , & Zhao, W. (2020). NLRP3 inflammasome—A key player in antiviral responses. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 211 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F. , Yu, T. , Du, R. , Fan, G. , Liu, Y. , Liu, Z. , … Guan, L. (2020). Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet, 395, 1054–1062. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuurbier, C. , Abbate, A. , Cabrera‐Fuentes, H. , Cohen, M. , Collino, M. , De Kleijn, D. , … Davidson, S. M. (2019). Innate immunity as a target for acute cardioprotection. Cardiovascular Research, 115, 1131–1142. 10.1093/cvr/cvy304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]