Key Message.

We propose a swift transition to an e‐health approach during the COVID‐19 pandemic, in order to provide preeminent treatment for patients with bipolar disorder. Guidelines regarding use of internet‐based programs, self‐monitoring platforms, and daily routine adjustments are offered. All recommendations are evidence‐based and offer safe directions for mental health professionals.

Learning Points

Transition to an online approach is needed in this moment of pandemic; closely monitoring of the circadian rhythm and sleep hours is crucial for mood stability in BD patients, and can be made via online platforms.

Flexibility and availability from mental health workers is key, we recommend more frequent clinical evaluations and check‐ups, all made via videoconferencing.

This unique moment may offer opportunity for self‐awareness and insight for both patients and mental health workers.

In the past few months, many lives have been impacted by the new COVID‐19 pandemic, which generated a need for social isolation and quarantine, impacting personal freedom, financial stability, and mental health. During this period, it is expected that many people will experience higher levels of anxiety and depression. Individuals with pre‐existing anxiety disorders (AD) and other psychiatric conditions are more vulnerable to the negative psychological consequences of pandemics. Individuals with bipolar disorder (BD) are at increased risk of developing AD, with roughly half of this population exhibiting it during the course of illness. 1 Recently published guidelines focus mainly on general mental health issues, whereas our clinical care review aims to provide specific guidelines for BD treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. All mental health approaches cited in this article are based on scientific evidence.

Although we recognize certain resistance in adopting internet‐based strategies, a rapid transition to e‐health is a crucial and preferred action for continuous treatment for people with BD diagnosis. 2 In terms of psychotherapy, an online approach using videoconference, is the best solution in order to maintain social distance, also allowing for an increase in treatment intensity when necessary, providing positive outcomes regarding general anxiety and mood disorders. In contrast, we do not advise an online approach for psychiatric emergencies, such as suicide attempts and ideation; both of which should be carefully assessed and dealt with in a personalized matter.

Regarding the psychological impact of online support groups mediated by mental health professionals, evidence points to a positive impact on the participants, providing them with a validating and empowering environment. Thus, the use of online support groups may allow BD patients to share coping strategies, while also providing encouragement during the COVID‐19 crisis, creating a supportive environment. Conversely, the steep increase in online exposure may lead to a higher frequency and intensity of social media use, which poses risks for developing depression and social anxiety.

We advise health care professionals to educate patients about the potential negative effects of social media overuse as opposed to a well‐balanced use, which can offer opportunities to promote a positive support system and social interactions. Another important issue for consideration is how to deal with the constant flow of news concerning the pandemic. We believe that providing patients with good quality information regarding common psychological reactions, such as elevated levels of stress and anxiety, during the actual circumstances is advised. However, we do not encourage BD patients to overexpose themselves to media news, as it may have a negative collateral effect.

Besides pharmacological and online psychotherapy interventions, BD patients may benefit from other adjunctive treatments and psychoeducation components, that have been already indicated as standard psychosocial treatment for BD, however, they should be reinforced at this moment. It is well‐known that sleep and circadian rhythm abnormalities in BD are associated with higher risks of mood episode recurrence as well as depressive symptoms. 3 This matter becomes especially critical during times of pandemic, since there is a higher disposition for unstructured days and a lack of routine, which might lead to an increased exposure to evening blue light due to online meeting and internet usage, associated with sleep and circadian rhythm abnormalities in BD patients. Nonetheless, this issue can be mitigated with the use of blue‐blocking glasses or adjustment to electronic light setting configuration. 3 Although blue light exposure may affect circadian rhythm, it is not the only cause of a possible disruption. In this sense, recent evidence indicates that the use of mindfulness‐based interventions, daily physical activity, and attention to diet should be implemented. 4 Therefore, we advise health workers to inquire, educate, and monitor stressors such as sleep, eating habits, activities, subsyndromic mood changes, and routine maintenance. Additionally, the use of electronic self‐ monitoring platforms, is recommended, since they can be monitored by the clinician in order to allow for effective responses from patients and adaptations over time, aiding in preventing the recurrence of mood episodes. 5 The following platforms and apps are easily accessible and evidence‐based and can be used with patients during the pandemic: Mindstrong App; Smiling Mind App; Downdog App; Headspace App; E‐mood Tracker Platform and Monsenso Platform.

Furthermore, BD has a high rate of comorbidity with substance abuse. With the necessity of quarantine and social isolation, self‐medication and alcohol abuse may become an escalating issue across all populations, which requires that this be given special attention by professionals specifically given vulnerabilities presented by BD patients.

In this delicate moment, increased flexibility and availability for scheduling sessions is advised for health care professionals, since patients will possibly present new demands, and in order to offer support and attentiveness regarding the patients’ mood fluctuations, episodes recurrence as well as other arising demands. We also anticipate the possibility of BD patients developing Post Traumatic Stress Disorder at a higher rate than the general population, as a collateral effect of the quarantine, as well as financial and personal losses related to the pandemic, reiterating the need for extreme focus on preventive measures.

Nevertheless, the COVID‐19 pandemic provides the entire community with challenges regarding previous preconceptions and models of work. Without distractions from our busy daily lives, this new experience can shed light on new insights and higher self‐awareness for patients as well as for health care workers. We must use this silver lining as a potential for self‐discovery, nurturing tolerance for new feelings and exercising patience toward ourselves and the surrounding community. Health care professionals from different areas, such as nurses; psychologists and doctors, may unite to reinforce the prescription of these psychological therapies, reviewing psychoeducation and reinforcing healthy living behaviors for BD, given the potential negative impact of physical distance on the prognosis and pathophysiology of the disorder. Ultimately, BD patients may benefit from this opportunity by being more aware of how slight shifts in their routines can have different effects in their moods and general stability (see Supplementary Material).

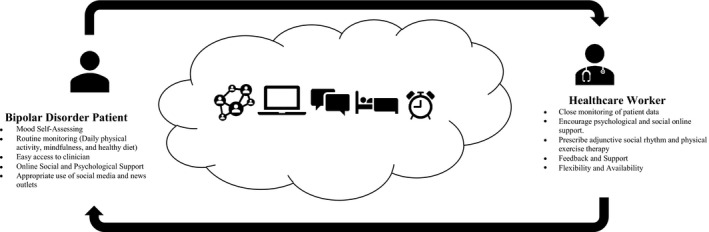

Finally, we reiterate the importance of health care workers striving to interact with patients in new and more flexible ways, in order to provide best possible care, considering specific needs that might arise to each patient during this unique and sensitive time. Special attention regarding the bond between BD patients and mental health professionals is of importance, considering a need for empathy with each individual and its necessities Matters regarding adherence to routine, mood self‐assessing, online social and psychological support, easy access to clinician and appropriate use of social media and news outlets should also be considered (see Figure 1). More importantly, mental health professionals are encouraged to provide patients with more flexible hours and availability, as well as to encourage adherence to the aforementioned adjunctive therapies, psychoeducational orientation and reinforcement of healthy living behaviors in order to prevent episode recurrence and minimize the possible psychological negative effects offered by the COVID‐19 pandemic (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Psychological and adjunctive therapies guidelines for BD treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic

AUTHORSHIP CONTRIBUTIONS

Luisa de Siqueira Rotenberg contributed to the conception, design, and drafting of the work and critically revised it for important intellectual content. Tatiana Cohab Khafif contributed to the conception, design, and drafting of the work and critically revised it for important intellectual content. Camila Nascimento contributed to the conception, design, and drafting of the work and critically revised it for important intellectual content. Rodrigo Dias contributed to the drafting and critically revised it for important intellectual content. Beny Lafer supervised the conception, design, and drafting of the work and critically revised it for important intellectual content.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Rodrigo Silva Dias is co‐founder and owner of DM Healthcare and Depression Innovation Advisory Board (Sanofi‐Aventis Brasil) since November 2019. All other authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Luisa de Siqueira Rotenberg was supported by CAPES Scholarship 88887.475730/2020‐00 during the preparation of this manuscript. CAPES Scholarship had no role in writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Tatiana CohabKhafif was supported by CAPES Scholarship 88887.461435/2019‐00 during the preparation of this manuscript. CAPES Scholarship had no role in writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Camila Nascimento was supported by FAPESP Scholarship 2017/07089‐8 the preparation of this manuscript. FAPESP Scholarship had no role in writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Rodrigo Silva Diashas no disclosures. BenyLafer was supported by FAPESP grant 17/07089‐8 during the preparation of this manuscript. FAPESP had no role in writing the manuscript or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1. Pavlova B, Perlis RH, Alda M, Uher R. Lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in people with bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(8):710‐717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912‐920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gottlieb JF, Benedetti F, Geoffroy PA, et al. The chronotherapeutic treatment of bipolar disorders: a systematic review and practice recommendations from the ISBD Task Force on Chronotherapy and Chronobiology. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(8):741‐773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(2):97‐170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Faurholt‐Jepsen M, Munkholm K, Frost M, Bardram JE, Kessing LV. Electronic self‐monitoring of mood using IT platforms in adult patients with bipolar disorder: a systematic review of the validity and evidence. BMC psychiatry. 2016;16(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material