1. INTRODUCTION

Novel coronavirus (SARS‐COV 2) pandemic has affected millions worldwide and the numbers are increasing exponentially. 1 A significant proportion of those affected are healthcare workers. 2 Adequate personnel protective equipment (PPE) are required to care for patients affected by COVID‐19, as it spreads through respiratory secretions and fomites. 3 With the dwindling pool of Healthcare personnel (HCP) and gross shortage of PPE, combating COVID‐19 becomes a challenge. 4

2. NEED FOR TELE‐HEALTHCARE

Approximately 85% of COVID‐19 affected patients have non severe disease and only 5% require intensive care. 5 Thus, many patients can be managed without any active intervention or physical presence of a HCP. Telemedicine helps in making remote clinical decisions and can act as an effective tool in above scenario. 6 , 7 It has been rediscovered as a potential tool to combat the novel coronavirus in many countries including China, USA, and Israel with successful benefits. However, the concept is still budding in developing nations and literature on its utility in an infectious pandemic is sparse.

3. CHALLENGES IN TACKLING COVID‐19 PANDEMIC

At an individual healthcare centre, multiple issues need to be addressed while handling COVID‐19 pandemic. Firstly, usual triaging system at emergency facilities seems inadequate to deal with the surge of cases. Secondly, shortage of PPE would force healthcare workers to work with whatever is available. Thirdly, frontline HCP are at an increased risk of getting infected. Fourthly, stationary used for documentation can act as a potential source of fomite transmission.

Roadblocks are evident in handling COVID‐19 pandemic at national level too. Inappropriate penetration of data to HCP has caused information adulteration and a knowledge gap, mandating need for wider dissemination of standard management guidelines across the country and tele‐health model can help in this aspect. With HCP from various specialities being mobilised for patient care, there exists a significant expertise gap. For instance, expertise to manage patients on mechanical ventilators could be lacking, thus making government efforts to provide ventilators on a large scale futile. Frontline HCP may not feel confident in managing COVID‐19 patients due to lack of training and expertise thereby creating a huge gap in patient care. Lack of public awareness and knowledge on national statistics, home care and self‐care during COVID‐19 pandemic accentuates the information gap at general population level. Utility of telemedicine to fulfill these major gaps appears as a novel solution.

4. PROPOSED TELE‐HEALTHCARE MODEL

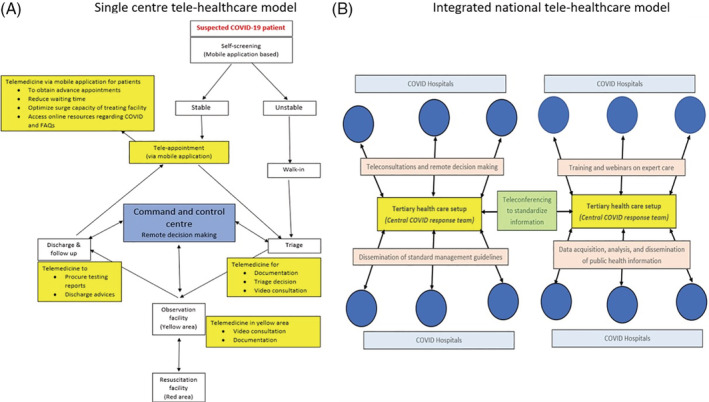

In this article, we discuss a single centre model for tele‐healthcare (Figure 1A) and an integrated model for functioning at national level (Figure 1B). At an individual facility, entry of a suspected COVID‐19 patient is based on self‐screening via mobile based application. Those deemed to be stable can obtain tele‐appointment and reach the facility. If symptoms are inconsistent with infectious disease, they can avoid unnecessary visits and prevent the overcrowding of hospital, thus preventing the surge. They can follow general infection prevention measures as described in the application. Sick patients can directly approach the healthcare facility.

FIGURE 1.

A, Single centre tele‐healthcare model. B, Integrated national tele‐healthcare model. The above illustration is original work of Vishakh C Keri and co‐authors [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

On reaching the hospital, patients will go through a two‐stage triage model which caters for history and examination, respectively. Documentation can be done on a simple mobile application‐based platform, accessed by all HCP of the team which could prove advantageous. Firstly, it aids in real time documentation and maintaining a closed loop of information transfer. Secondly, it eases the decision‐making process for HCP mobilised from differing fields of expertise to combat COVID‐19 as it is a simple checkbox format. Thirdly, since no stationary will be used and examining doctor will not handle the device nor the patient encounters it, risk of fomite transmission is minimised.

If the patient is sick, he is shifted to yellow area. Main responsibility here will be strict monitoring and early identification of clinical deterioration. Video conferencing based remote decision‐making model from a central command centre setup at the facility can be implemented to guide the on‐floor HCP. This reduces the number of on‐floor HCP, thus reducing unnecessary exposure and PPE use. Most importantly it can help in optimal utilisation of HCP from diverse medical background who can be guided on decisions remotely through expert opinions. This model can be replicated and adapted to various emergency response centres across the country.

Telemedicine at individual centres are beneficial, and its utility can be expanded throughout the country to deliver uniform care. Healthcare systems have been stratified into remote Primary Healthcare Centres (PHC) to large tertiary healthcare setups. We visualise a hub and spokes model 8 to deliver telemedicine across the country. In this model (Figure 1B), tertiary care setups are linked to district and primary health care systems. Tertiary care setup with its set of specialist doctors from various fields of General medicine, Infectious diseases, Pulmonary medicine, Critical care and Emergency medicine and others will be available round the clock online in their central COVID response centre. They will provide services including education, training and expert video consults to individual COVID care facilities in their jurisdiction. In addition, doctors at the PHC can freely contact doctors at the tertiary centres from their point of patient care to clarify doubts and feel confident about managing. Specialists can take rounds of patients in PHCs from their central COVID response centres through video conferencing and can even talk to the patients. This increases the confidence of patients on the specialist care they are receiving. It can also help policy makers at the tertiary care level understand ground realities and modify policies timely.

Such a countrywide tele healthcare model for developing countries can make expertise reach remote corners of the country, thus allaying fears, myths and educating the healthcare workers to combat COVID‐19.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors have no competing interests.

Keri VC, R.L B, Sinha TP, Wig N, Bhoi S. Tele‐healthcare to combat COVID‐19 pandemic in developing countries: A proposed single centre and integrated national level model. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2020;35:1617–1619. 10.1002/hpm.3036

REFERENCES

- 1. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports.

- 2. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061‐1069. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS‐CoV‐2 as compared with SARS‐CoV‐1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1564‐1567. 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid‐19 in Italy — ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic's front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1873‐1875. 10.1056/NEJMp2005492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708‐1720. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lurie N, Carr BG. The role of telehealth in the medical response to disasters. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:745‐746. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hollander JE, Carr BG. Virtually perfect? Telemedicine for Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1679‐1681. 10.1056/NEJMp2003539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL. The hub‐and‐spoke organization design: an avenue for serving patients well. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:457. 10.1186/s12913-017-2341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]