Editor

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has swept the globe, seriously threatening the public health. We read with great interest the researches which focused on the abdominal pain and pancreatic injury caused by COVID-191,2. In our clinical experience, a large number of patients who confirmed as COVID-19 present gastrointestinal symptoms along with or before respiratory symptoms, which are more difficult to recognize.

We comprehensively reviewed studies on gastrointestinal symptoms of COVID-19 patients from Dec 1, 2019 to April 20, 2020. A total of 25 210 patients were included. The median age (IQR) was 45·2(36·6-55·7) years. 43·4% of the patients were male. Seventy-five (81%) studies were from China, eighteen (19%) studies were from other countries. Among the studies in China, twenty-nine (39%) were from Hubei Province. The number of studies on adult, pregnant women and pediatric patients were 72, 7, and 14, respectively.

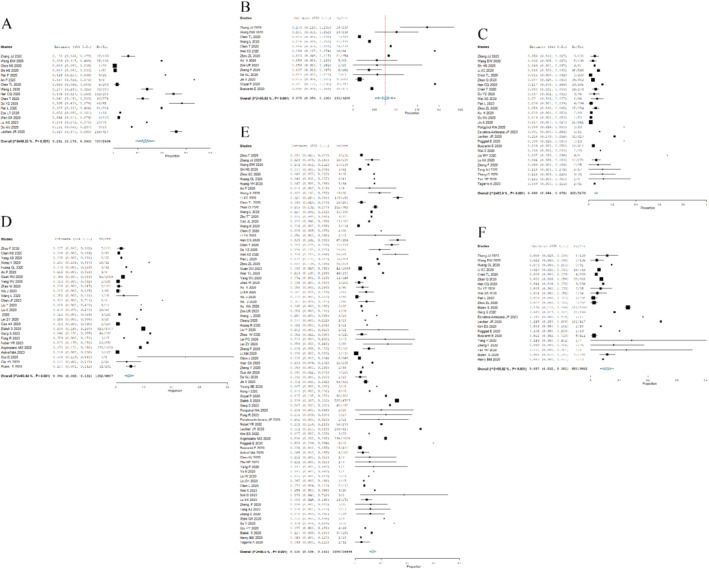

The incidence of all gastrointestinal symptoms was 18·6% (95% CI: 15·7%-21·6%). As shown in Fig. 1, anorexia (26·1%, 95% CI: 17·6%-34·5%) and diarrhea (13·5%, 95% CI: 10·8%-16·1%) were the most common gastrointestinal symptoms, followed by nausea and vomiting (9·4%, 95%CI: 5·8%-13·1%), nausea (7·5%, 95% CI: 5·0%-10·0%), vomiting (6·0%, 95% CI: 4·4%-7·6%). Abdominal pain was relatively rare (5·7%, 95% CI: 3·2%-8·1%). In China, the incidence of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea was significantly higher in patients within Hubei Province than outside Hubei. And the incidence of diarrhea and abdominal pain was significantly lower in patients from China than from other countries. Abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting were more prevalent in pediatric patients than adults but there was no significant statistical difference. The incidence of diarrhea was higher in adults than in pediatric patients and pregnant women, but there was no significant difference.

Fig. 1.

The forest plots of the incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms

A: Anorexia; B: Nausea; C: Vomiting; D: Nausea and vomiting; E: Diarrhea; F: Abdominal pain.

All Gastrointestinal symptoms correlate with a more severe disease course and a larger proportion of intensive care unit (ICU) admission. The pooled prevalence of all gastrointestinal symptoms was higher in COVID-19 patients with severe disease than with non-severe disease (24·41% versus 16·31%, P < 0·001). The proportion of ICU admission in patients with and without all gastrointestinal symptoms was 9·81% and 6·70%, respectively, and there was a significant difference (P = 0·008). Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms had a smaller proportion of mechanical ventilation and death. Female and elderly patients were easier to suffer from gastrointestinal injury.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor is a critical cell receptor for SARS-CoV-2 to invade the host cells. SARS-CoV-2 directly invades the digestive tract through binding with ACE2 receptors in glandular cells of gastric, duodenal and rectal epithelial cells, as well as in enterocytes of small intestinal3. Moreover, after infected with SARS-CoV-2, the“gut-lung” axis and the interaction between intestinal microbiota and pro-inflammatory cytokines may also lead to the injury of the gastrointestinal tract4. However, most patients were treated with antibiotics (abidol, ribavirin) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), so drug-associated gastrointestinal symptoms should be distinguished5.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common clinical manifestations of COVID-19. When accessing surgical patients, clinicians should inquiry on whether patients complain about any gastrointestinal discomfort in detail, identify COVID-19 in time, and reduce the risk of infection during surgery.

Acknowledgement

We also offer supplementary figures and tables in supplementary materials.

Ethics approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Originality

Any republication of the data will not constitute redundant publication, will not breach copyright, and will reference the original publication.

References

- 1. Mukherjee R, Smith A, Sutton R. Covid-19-related pancreatic injury. Br J Surg 2020; 107: e190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saeed U, Sellevoll HB, Young VS, Sandbaek G, Glomsaker T, Mala T. Covid-19 may present with acute abdominal pain. Br J Surg 2020; 107: e186–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, Liu Y, Li X, Shan H. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 1831–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhang D, Li S, Wang N, Tan H, Zhang Z, Feng Y. The cross-talk between gut microbiota and lungs in common lung diseases. Front Microbiol 2020; 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00301 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Han C, Duan C, Zhang S, Spiegel B, Shi H, Wang Wet al. Digestive symptoms in COVID-19 patients with mild disease severity: clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115: 916–923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]