In early 2020, the rapid spread of SARS‐CoV‐2 from China to the rest of the world produced a global pandemic affecting over 100 countries. 1 To limit viral transmission and mitigate the disease burden, most countries adopted lockdown measures. The Italian outbreak emerged in the north of the country (Lombardy, Veneto, and Emilia‐Romagna regions) in late February 2020, and later spread to the rest of the peninsula. 2 A nationwide school closure was ordered on 5 March, and students and teachers have been required to switch to distance‐learning programs. Disruption of daily routines and social isolation may have deleterious effects on children's health, especially for those with mental health needs and pre‐existing chronic diseases. 3

Chronic tic disorders (CTD) and Tourette's syndrome (TS) are childhood‐onset neurodevelopmental disorders often associated with neuropsychiatric comorbidities, especially attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). 4 , 5 Children with TS and CTD could be at high risk for lockdown‐related worsening of their conditions.

Patients with TS (n = 58) and CTD (n = 22) were recruited from the Movement Disorders Outpatient Clinic of Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital. Sixteen patients met the diagnostic criteria for ADHD (ADHD+), 18 for OCD (OCD+), and 12 for both (ADHD+‐OCD+). The remaining 34 were classified as the isolated tic disorder subgroup. Other comorbidities encountered included anxiety, oppositional‐defiant disorder, academic difficulties, and explosive outbursts (for details of the study design and the cohort description, see Figure S1 and Table S1 in Supporting information).

Parents and/or children were interviewed with structured telephone questionnaires. The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee and parents gave their informed consent; when directly involved in the interview, children gave their own assent.

Tic severity (according to the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale [YGTSS]), 6 OCD symptoms (according to the Children's Yale–Brown Obsessive–Compulsive Scale [CY‐BOCS]) 7 and new‐onset symptoms were assessed during the fourth and fifth week of nationwide lockdown. Furthermore, we rated the guardian's impression of symptoms’ worsening during the lockdown using a simplified 5‐grade scale from improved or unchanged to extreme worsening (see Appendix S1).

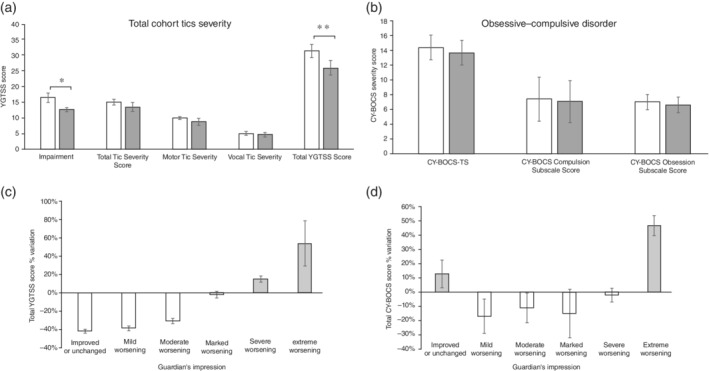

We found a significant reduction of overall YGTSS scores (Fig. 1a) in the entire cohort with no difference among groups, comparing pre‐ and post‐lockdown. Considering the two components of the YGTSS, we found that the overall reduction was significantly due to the YGTSS's Tic‐Related Impairment score (−23.45%), while scores for the Motor and Vocal Tic Severity subscales (number, frequency, intensity, complexity, and interference of tics) were stable or reduced to a lesser extent.

Fig. 1.

(a) ( ) Pre‐lockdown and (

) Pre‐lockdown and ( ) post‐lockdown Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) subscale scores in the total cohort. (b) (

) post‐lockdown Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) subscale scores in the total cohort. (b) ( ) Pre‐lockdown and (

) Pre‐lockdown and ( ) post‐lockdown comparison of CY‐BOCS score. (c) Mean percentage change of YGTSS scores according to the guardian's impression. (d) Mean percentage change of CY‐BOCS‐TS according to the guardian's impression. TS, total score. Error bars indicate standard errors. *P < 0.05 on paired t‐test. **P < 0.01 on paired t‐test.

) post‐lockdown comparison of CY‐BOCS score. (c) Mean percentage change of YGTSS scores according to the guardian's impression. (d) Mean percentage change of CY‐BOCS‐TS according to the guardian's impression. TS, total score. Error bars indicate standard errors. *P < 0.05 on paired t‐test. **P < 0.01 on paired t‐test.

The severity levels of obsessive–compulsive symptoms were stable before and during the lockdown (Fig. 1b) in patients with OCD symptoms (OCD+ plus ADHD+OCD+ = 30). Nevertheless, compared to the pre‐lockdown period, an increasing proportion of patients presented rituals involving other persons and checking compulsions (+13.30%). Repeating behaviors were less frequently reported (−13.40%), whereas an increase in the frequency of contamination obsessions was encountered (+26.60%). Surprisingly, this did not coincide with an increase in washing/cleaning compulsions (see Table S2 in Supporting information for a detailed description).

New symptoms during lockdown, particularly anxiety and irregular sleep patterns, were reported in about half of the patients. Sleep disturbances, especially in the subgroups with comorbid ADHD and OCD, affected both sleep length and sleep patterns, with difficulties in falling asleep, higher rate of co‐sleeping, and frequent awakenings. Both of these disturbances can be related to the lack of daily routine 8 and to the co‐occurring anxiety (anxiety‐induced insomnia). 9 Less frequently, previously unnoticed ADHD symptoms, explosive outbursts, or mood deflection were reported. The occurrence of explosive outbursts during school closure raises serious concerns about their management by the guardians because of the prohibition of outdoor activities and the difficulties in dealing with these rage attacks domestically. A new onset of eating disorders (restricted and increased eating habits or avoidant/restrictive food intake) was reported in the ADHD+OCD+ group (Table S3 in Supporting information).

Finally, interestingly, the contribution of tic and OCD severity to parents’ impression was more evident in patients rated with the most severe degrees of worsening (Fig. 1c,d). The mismatch between parental impression and tic and OCD severity measures suggests that lockdown may exert different effects on tics and behavioral symptoms, and that global worsening could be related to other neuropsychiatric comorbidities.

In conclusion, TS and CTD patients experienced a significant reduction of tic severity, mainly due to the decrease in tic‐related impairment, likely reducing the burden of tic in social context (school, playful activities). Nevertheless, prolonged social distancing led to the appearance of novel neuropsychiatric symptoms, especially in children with pre‐existing comorbidities.

Although our study involves some limitations, such as its cross‐sectional nature and its retrospective evaluation of the pre‐lockdown severity of tics and OCD, our data shed light on the need to assess the mental health burden of this unprecedented situation in vulnerable groups of children.

Disclosure statement

Nothing to declare.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Timeline of the study and the cohort description.

Table S1. Main demographic and clinical features of the total cohort and of the subgroups.

Table S2. Obsessions and compulsions before and after the lockdown.

Table S3. New‐onset symptoms during lockdown.

Appendix S1. Supporting information.

References

- 1. Cascella M, Rajnik M, Cuomo A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, evaluation and treatment of coronavirus (COVID‐19). In: StatPearls. StatPearls, Treasure Island, FL, 2020. [Cited 30 April 2020]. Available from URL: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID‐19 and Italy: What next? Lancet 2020; 395: 1225–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brooks SK, Smith LE, Webster RK et al. The impact of unplanned school closure on children's social contact: Rapid evidence review. Euro Surveill. 2020; 25: 2000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cavanna AE. Gilles de la Tourette syndrome as a paradigmatic neuropsychiatric disorder. CNS Spectr. 2018; 23: 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hirschtritt ME, Lee PC, Pauls DL et al. Lifetime prevalence, age of risk, and genetic relationships of comorbid psychiatric disorders in Tourette syndrome. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 325–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leckman JF, Riddle MA, Hardin MT et al. The Yale Global Tic Severity Scale: Initial testing of a clinician‐rated scale of tic severity. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 1989; 28: 566–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bejerot S, Edman G, Anckarsäter H et al. The Brief Obsessive–Compulsive Scale (BOCS): A self‐report scale for OCD and obsessive–compulsive related disorders. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2014; 68: 549–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brazendale K, Beets MW, Weaver RG et al. Understanding differences between summer vs. school obesogenic behaviors of children: The structured days hypothesis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017; 14: 100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020; 395: 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Timeline of the study and the cohort description.

Table S1. Main demographic and clinical features of the total cohort and of the subgroups.

Table S2. Obsessions and compulsions before and after the lockdown.

Table S3. New‐onset symptoms during lockdown.

Appendix S1. Supporting information.