Abstract

The negative outcomes of COVID‐19 diseases respiratory distress (ARDS) and the damage to other organs are secondary to a “cytokine storm” and to the attendant oxidative stress. Active hydroxyl forms of vitamin D are anti‐inflammatory, induce antioxidative responses, and stimulate innate immunity against infectious agents. These properties are shared by calcitriol and the CYP11A1‐generated non‐calcemic hydroxyderivatives. They inhibit the production of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, downregulate NF‐κΒ, show inverse agonism on RORγ and counteract oxidative stress through the activation of NRF‐2. Therefore, a direct delivery of hydroxyderivatives of vitamin D deserves consideration in the treatment of COVID‐19 or ARDS of different aetiology. We also recommend treatment of COVID‐19 patients with high‐dose vitamin D since populations most vulnerable to this disease are likely vitamin D deficient and patients are already under supervision in the clinics. We hypothesize that different routes of delivery (oral and parenteral) will have different impact on the final outcome.

Keywords: COVID‐19, cytokine storm, oxidative stress, SARS‐CoV‐2, vitamin D, vitamin D‐hydroxyderivatives

1. BACKGROUND

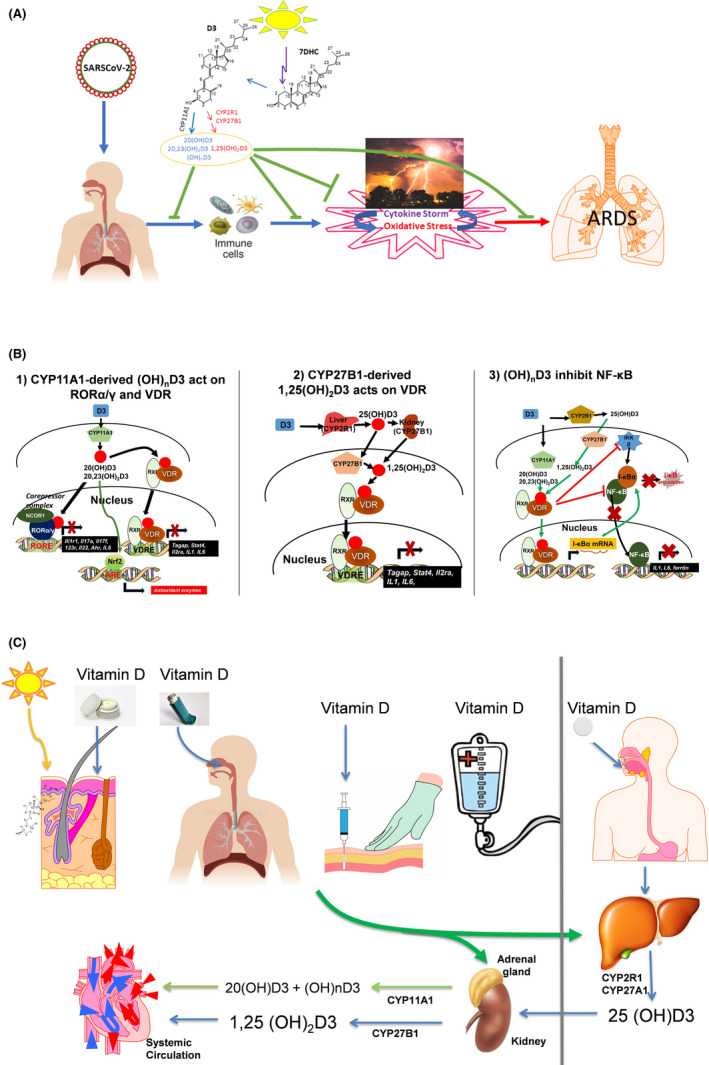

The COVID‐19 is currently the foremost health issue in the world. SARS‐CoV‐2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus) is an enveloped positive strain RNA virus in the family Coronaviridae, which also includes the virus SARS‐CoV‐1 (which was another outbreak in 2002‐2003).[ 1 ] COVID‐19 has a fatality rate up to ~5%, which is several times higher than influenza.[ 2 , 3 ] The leading cause of death in the patients is due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)[ 2 ] induced by pro‐inflammatory responses and oxidative stress Figure 1A.

FIGURE 1.

Vitamin D as the solution to the COVID‐19 illness. (A) Hydroxyderivatives of vitamin D3, by inhibition of cytokine storm and oxidative stress, will attenuate ARDS and multiorgan failure induced by COVID‐19. (B) Mechanism of action of canonical and non‐canonical vitamin D‐hydroxyderivatives. Vitamin D signalling in mononuclear cells downregulates inflammatory genes and suppresses oxidative stress. VDR, vitamin D receptor; RXR, retinoid X receptor; ROR, retinoic acid orphan receptor, RORE, ROR response element; ARE, antioxidant response element; VDRE, vitamin D response element; NRF2, transcription factor NF‐E2‐related factor 2. (C) Different routes of vitamin D delivery will impact vitamin D activation pattern

Vitamin D is a fat‐soluble prohormone, which after production in the skin or oral delivery affects important physiological functions in the body including regulation of the innate and adaptive immunity.[ 4 , 5 , 6 ] Vitamin D can be activated through canonical and non‐canonical pathways Figure 1A. In the former, it is metabolized to 25‐hydroxyvitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) by CYP2R1 and CYP27A1 in the liver with further metabolism in the kidney to the biologically active 1,25‐dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3) by CYP27B1.[ 7 , 8 , 9 ] This metabolism also occurs in a variety of organs, including skin and the immune system.[ 7 , 9 ]

An alternative pathway of vitamin D activation by CYP11A1 leads to production of more than 10 metabolites some of which are non‐calcemic even at high doses.[ 8 , 10 , 11 ] These hydroxyderivatives, including 20(OH)D3 and 20,23(OH)2D3, are produced in humans.[ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ] In addition, 20(OH)D3 has been detected in the honey, which defines it as a natural product.[ 16 ] CYP11A1 is expressed not only in adrenals, placenta and gonads but also in immune cells and other peripheral organs.[ 17 ]

Both 1,25(OH)2D3‐ and non‐calcemic CYP11A1‐derived metabolites use various, although partially overlapping, mechanisms in enacting their anti‐inflammatory and antioxidative effects Figure 1B. 1,25(OH)2D3 mediates many of its anti‐inflammatory and anti‐microbial effects through the vitamin D receptor (VDR).[ 6 , 9 ] 1,25(OH)2D3 can also inhibit the mitogen‐activated protein kinase (MAPK) and NF‐kB signalling.[ 4 , 9 ]

The non‐calcemic CYP11A1‐derived vitamin D compounds also have their own methods to fight inflammation Figure 1B. 20(OH)D3, and their downstream hydroxyderivatives act on VDR as biased agonists.[ 11 , 18 , 19 ] They also act as inverse agonists on the retinoic acid‐related orphan receptors, RORα and RORγ, transcription factors with critical roles in several immune cells and immune responses[ 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ] Figure 1B. In addition, CYP11A1‐derived vitamin D3 metabolites and classical 1,25(OH)2D3 can act as agonists on aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR).[ 24 ] Although binding pocket of this receptor can accommodate many different molecules, we believe that secosteroidal signal transduction can be linked to detoxification and antioxidative action[ 11 ] or downregulation of pro‐inflammatory responses.[ 25 ]

2. PREMISES

2.1. ARDS and other adverse effects of COVID‐19 are induced by cytokine storm

A leading cause of ARDS is “cytokine storm,” a hyperactive immune response triggered by the viral infection Figure 1A.[ 2 , 26 ] It is initiated when the pattern recognition receptor of the innate immune cells recognizes the pathogen‐associated molecular pattern from a pathogen such as bacteria or virus.[ 26 , 27 ] The immune cells then release all types of cytokines (interferons, interleukins 1, 6 and 17, chemokines, colony‐stimulating factors, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)) leading to hyperinflammation and organ damage.[ 27 , 28 , 29 ] In the lungs, alveolar cells are targeted leading to acute lung injury and subsequently ARDS.[ 27 , 30 ] In severe cases of COVID‐19, other organs and systems are also damaged.[ 2 , 3 ] Thus, it is crucial to find ways to prevent the “cytokine storm” from going out of control. Although different drugs have been suggested to fight the cytokine storm,[ 26 , 27 ] they have mixed results and in certain cases can even worsen the disease.[ 27 ] Thus, there is a great need for alternative therapies.

Oxidative stress is also involved in the development of ARDS through action of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS).[ 31 , 32 , 33 ] The production of ROS and RNS can be triggered by pathogens promoting the secretion of cytokines, which stimulate ROS production thereby producing a positive feedback loop Figure 1A.[ 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 ] Nuclear factor erythroid 2p45‐related factor 2 (NRF‐2) is a transcription factor that plays a role in the detection of excessive ROS and RNS and induction of mechanisms counteracting the oxidative damage.[ 36 ] NRF‐2 loss due to ROS can lead to elevation in pro‐inflammatory cytokine levels and stronger inflammatory responses to stimuli.[ 31 , 36 ]

2.2. Anti‐inflammatory and antioxidative activities of active forms of vitamin D

There is a strong experimental evidence that active forms of vitamin D including the classical 1,25(OH)2D3 and novel CYP11A1‐derived hydroxyderivatives[ 8 , 11 ] exert potent anti‐inflammatory activities including inhibition of IL‐1, IL‐6, IL‐17, TNFα and INFγ production or other pro‐inflammatory pathways (Table S1).[ 11 , 18 , 20 , 37 , 38 ] The mechanism of action includes downregulation of NF‐κΒ involving action on VDR and inverse agonism on RORγ leading to attenuation of Th17 responses Figure 1B.[ 11 , 18 , 20 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] These compounds also induce antioxidative and reparative responses with mechanism of action involving activation of NRF‐2 and p53.[ 11 , 39 , 40 , 41 ]

2.3. Antiviral effects of active forms of vitamin D

Low vitamin D status in winter permits viral epidemics, and vitamin D supplementation could reduce the incidence, severity and risk of viral diseases.[ 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 ] In addition, several reports have found a strong association between vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency and enhanced COVID‐19 severity and mortality[ 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 , 53 ] with the most recent study defining low plasma 25(OH)D3 as an independent risk factor for COVID‐19 infection and hospitalization.[ 54 ] Therefore, we retrospectively analysed microarray data of human epithelial cells treated with 20,23(OH)2D3 and 1,25(OH)2D3.[ 24 ] We found the downregulation of pathways connected with influenza infection and viral RNA transcription, translation, replication, life cycle and of host interactions with influenza factors with 20,23(OH)2D3 expressing higher antiviral potency Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the microarray data deposited at NCBI GEO (GSE117351)

| Antiviral properties of vitamin D3‐hydroxyderivatives | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactome pathway | GSEA for 20,23(OH)2D3 | GSEA for 1,25(OH)2D3 | ||||||

| NES | P‐value | FDR | Direction | NES | P‐value | FDR | Direction | |

| Viral mRNA Translation | −2.818 | .00 | 0.012 | Down | −3.601 | .00 | 0.00 | Down |

| Viral Messenger RNA Synthesis | −2.513 | .00 | 0.013 | Down | −2.405 | .00 | 1.860 | Down |

| Influenza Infection | −3.171 | .00 | 3.907 | Down | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ |

| Influenza Viral RNA Transcription & Replication | −3.206 | .00 | 3.434 | Down | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ |

| Host Interactions with Influenza Factors | −2.249 | .00 | 0.018 | Down | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ |

| HIV Life Cycle | −2.070 | .00 | 0.023 | Down | −2.503 | .00 | 7.788 | Down |

| Late Phase of HIV Life Cycle | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ | −2.658 | .00 | 2.614 | Down |

| Host Interactions with HIV factors | −3.340 | .00 | 1.354 | Down | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ | ¨ |

Abbreviations: NES, Normalized Enriched Score; FDR, False Discovery Rate; (¨), the effect is absent.

While 1,25(OH)2D3 has the limitation imposed by the toxicity that includes hypercalcemia,[ 7 , 9 ] CYP11A1‐derived 20(OH)D3, 20(OH)D2 and 20,23(OH)2D3 are not toxic and non‐calcemic at very high doses (3‐60 µg/kg) at which 1,25(OH)2D3 and 25(OH)D3 are calcemic.[ 24 , 55 , 56 , 57 , 58 ]

3. HYPOTHESIS

The hyperinduction of pro‐inflammatory cytokines production (cytokine storm), further magnified by oxidative stress induced by the viral infection or cytokines themselves, acting reciprocally in self‐amplifying circuitry, gradually damage/destroy the affected organs leading to death in the severe cases of COVID‐19 infection Figure 1A. A solution to the problem fulfilling above premises are active forms of vitamin D including the classical 1,25(OH)2D3 and 25(OH)D3 (precursors to 1,25(OH)2D3)[ 5 , 7 , 9 , 45 , 59 , 60 ] and novel CYP11A1‐derived hydroxyderivatives including 20(OH)D3 and 20,23(OH)2D3.[ 8 , 11 , 61 ] The former are FDA approved and can immediately be used in the clinic, while the latter are still not approved yet although they fulfil the definition of natural products. They would both terminate “cytokine storm” and oxidative stress with possible antiviral activity to rescue the patient from the death path Figure 1. Their preferable routes of delivery are listed in Figure 1C to reach immediately the most affected organs. In this context, active hydroxy forms of vitamin D2 should also be considered.[ 9 , 24 , 62 , 63 ]

As relates to the vitamin D precursor, it is reasonable to propose that patients are admitted with COVID‐19 infection to receive as soon as possible 200 000 IU of vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 followed by 4000‐10 000 IU/day, if justifiable.[ 45 , 64 ] Vitamin D3 at 200 000 IU orally has been used to attenuate inflammatory responses induced by the sunburn.[ 65 ] It must be noted that application of 250 000‐500 000 IU of vitamin D was reported be safe in critically ill patients and was associated with decreased hospital length of stay and improved ability of the blood to carry oxygen (reviewed in [ 66, 67 ]

4. RELEVANCE AND PERSPECTIVE

Different routes of delivery of vitamin D precursor can have a profound effect on the final panel of circulating in the body vitamin D derivatives Figure 1C. Vitamin D delivered orally during the passage through the liver is hydroxylated to 25(OH)D,[ 7 ] which is not recognized by CYP11A that only acts on its precursor, vitamin D itself.[ 68 ] This likely results in 30 times lower concentration of 20(OH)D3 in serum in comparison with 25(OH)D3.[ 14 ] However, its levels are higher than that of 25(OH)D3 in the epidermis, a peripheral site of vitamin D3 activation.[ 14 ] Therefore, adequate systemic (adrenal gland) or local (immune system) production of CYP11A1‐derived vitamin D hydroxyderivatives would require parenteral delivery of vitamin D. These routes of vitamin D precursor delivery could include sublingual tablets, intra‐muscular, subcutaneous or intravenous injections as well as its aerosolized form of delivery to the lung Figure 1C. As relates CYP11A1‐derived products, these would be predominantly generated in the adrenal gland for systemic purposes. However, they can also be generated in peripheral organs expressing CYP11A1 including skin and immune system.[ 17 , 69 ]

Since vitamin D is readily available, easy to use and relatively nontoxic, it can represent an immediate solution to the problems at relatively high doses, since populations most vulnerable to negative outcome of COVID‐19 disease are likely vitamin D deficient and the patients are already under supervision in the hospital environment and are monitored for adverse effects. Vitamin D toxicity is typically not observed until extremely high doses of vitamin D in the range of 50,000‐100,000 IUs are used daily for several months or years.[ 70 ] Doses up to 500 000 IUs have been routinely given to nursing home patients twice a year in Scandinavian countries to reduce risk for fracture without any evidence of vitamin D intoxication including hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia and soft tissue calcification.[ 70 ]

In addition, we believe that routes of delivery are likely to impact the final outcome, because bypassing liver vitamin D3 will also be accessible to CYP11A1 for metabolism in organs expressing this enzyme.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Michael F. Holick is on the Speakers Bureau for Abbott, former consultant for Quest diagnostics, and a consultant Ontometrics Inc. Other authors declare no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

RMS, CR and ATS designed figures and concept and wrote the paper. JS performed bioinformatics analysis and prepared Table 1 and Table S1. MFH, MA and AMJ wrote the paper.

Supporting information

Table S1. Comparison of the inhibition of inflammatory gene expression in epidermal keratinocytes by 20,23(OH)2D3 with 1,25(OH)2D3 based on retrospective analysis of microarray data deposited at the NCBI GEO (GSE117351). The values represent relative fold change in the gene expression

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Writing of this letter was in part supported by the NIH grants 1R01AR073004 and R01AR071189 to ATS and VA merit 1I01BX004293‐01A1 to ATS and R21 AI152047‐01A1 to CR and ATS.

Slominski RM, Stefan J, Athar M, et al. COVID‐19 and Vitamin D: A lesson from the skin. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29:885–890. 10.1111/exd.14170

Contributor Information

Chander Raman, Email: chanderraman@uabmc.edu.

Andrzej T. Slominski, Email: aslominski@uabmc.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Coronaviridae Study Group of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses , Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 536.32123347 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehta P., McAuley D. F., Brown M., Sanchez E., Tattersall R. S., Manson J. J., Across Speciality Collaboration H. L. H., Lancet 2020, 395, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang C., Shi L., Wang F. S., Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5(5), 428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abhimanyu C. A. K., Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2017, 16, 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wacker M., Holick M. F., Dermatoendocrinol. 2013, 5, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dankers W., Colin E. M., van Hamburg J. P., Lubberts E., Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Holick M. F., Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007, 357, 266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tuckey R. C., Cheng C. Y. S., Slominski A. T., J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 186, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bikle D. D., J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvz038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Li W., Yi A. K., Postlethwaite A., Tuckey R. C.. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2014, 144(Pt A), 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Slominski A. T., Chaiprasongsuk A., Janjetovic Z., Kim T. K., Stefan J., Slominski R. M., Hanumanthu V. S., Raman C., Qayyum S., Song Y., Song Y., Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2020, 78, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Shehabi H. Z., Semak I., Tang E. K., Nguyen M. N., Benson H. A., Korik E., Janjetovic Z., Chen J., Yates C. R., FASEB J. 2012, 26, 3901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Shehabi H. Z., Tang E. K., Benson H. A., Semak I., Lin Z., Yates C. R., Wang J., Li W., Tuckey R. C., Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2014, 383, 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Li W., Postlethwaite A., Tieu E. W., Tang E. K., Tuckey R. C., Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Li W., Tuckey R. C., Classical and non‐classical metabolic transformation of vitamin D in dermal fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2016, 25, 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim T. K., Atigadda V., Brzeminski P., Fabisiak A., Tang E. K., Tuckey R. C., Slominski A. T., Molecules 2020, 25(11). 10.3390/molecules25112583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Slominski R. M., Tuckey R. C., Manna P. R., Jetten A. M., Postlethwaite A., Raman C., Slominski A. T., Genes Immun. 2020, 21, 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lin Z., Marepally S. R., Goh E. S. Y., Cheng C. Y., Janjetovic Z., Kim T. K., Miller D. D., Postlethwaite A. E., Slominski A. T., Tuckey R. C., Peluso‐Iltis C.. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kim T. K., Wang J., Janjetovic Z., Chen J., Tuckey R. C., Nguyen M. N., Tang E. K., Miller D., Li W., Slominski A. T., Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012, 361, 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Takeda Y., Janjetovic Z., Brożyna A. A., Skobowiat C., Wang J., Postlethwaite A., Li W., Tuckey R. C., Jetten A. M., FASEB J. 2014, 28, 2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jetten A. M., Cook D. N., Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2020, 60, 371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Hobrath J. V., Oak A. S., Tang E. K., Tieu E. W., Li W., Tuckey R. C., Jetten A. M., J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 173, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jetten A. M., Takeda Y., Slominski A., Kang H. S., Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 8, 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Janjetovic Z., Brożyna A. A., Żmijewski M. A., Xu H., Sutter T. R., Tuckey R. C., Jetten A. M., Crossman D. K., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. 10.3390/ijms19103072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gutierrez‐Vazquez C., Quintana F. J., Immunity 2018, 48, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liu Q., Zhou Y. H., Yang Z. Q., Cell Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tisoncik J. R., Korth M. J., Simmons C. P., Farrar J., Martin T. R., Katze M. G., Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 76, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pugin J., Ricou B., Steinberg K. P., Suter P. M., Martin T. R., Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1996, 153(6 Pt 1), 1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen G., Wu D., Guo W., Cao Y., Huang D., Wang H., Wang T., Zhang X., Chen H., Yu H., Zhang X., J. Clin. Invest. 2020, 130(5), 2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuiken T., Fouchier R. A., Schutten M., Rimmelzwaan G. F., G. Van Amerongen , D. Van Riel , Laman J. D., T. De Jong , G. Van Doornum , Lim W., Ling A. E., Lancet 2003, 362, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schieber M., Chandel N. S., Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ye S., Lowther S., Stambas J., J. Virol. 2015, 89, 2672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vlahos R., Stambas J., Bozinovski S., Broughton B. R., Drummond G. R., Selemidis S., PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1001271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. To E. E., Vlahos R., Luong R., Halls M. L., Reading P. C., King P. T., Chan C., Drummond G. R., Sobey C. G., Broughton B. R., Starkey M. R., Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Imai Y., Kuba K., Neely G. G., Yaghubian‐Malhami R., Perkmann T., G. van Loo , Ermolaeva M., Veldhuizen R., Leung Y. C., Wang H., Liu H., Cell 2008, 133, 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lee C., Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2018, 2018, 6208067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Janjetovic Z., Tuckey R. C., Nguyen M. N., Thorpe E. M. Jr, Slominski A. T., J. Cell Physiol. 2010, 223, 36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Janjetovic Z., Zmijewski M. A., Tuckey R. C., DeLeon D. A., Nguyen M. N., Pfeffer L. M., Slominski A. T., PLoS One 2009, 4, e5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chaiprasongsuk A., Janjetovic Z., Kim T. K., Tuckey R. C., Li W., Raman C., Panich U., Slominski A. T., Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 155, 87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chaiprasongsuk A., Janjetovic Z., Kim T. K., Jarrett S. G., D'Orazio J. A., Holick M. F., Tang E. K., Tuckey R. C., Panich U., Li W., Slominski A. T., Redox Biol. 2019, 24, 101206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Slominski A. T., Janjetovic Z., Kim T. K., Wasilewski P., Rosas S., Hanna S., Sayre R. M., Dowdy J. C., Li W., Tuckey R. C., J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 148, 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Teymoori‐Rad M., Shokri F., Salimi V., Marashi S. M., Rev. Med. Virol. 2019, 29, e2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Huang F., Zhang C., Liu Q., Zhao Y., Zhang Y., Qin Y., Li X., Li C., Zhou C., Jin N., Jiang C., PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jakovac H., Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grant W. B., Lahore H., McDonnell S. L., Baggerly C. A., French C. B., Aliano J. L., Bhattoa H. P., Nutrients. 2020, 12(4). 10.3390/nu12040988 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng R. Z., Med Drug Discov. 2020, 5, 100028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. D'Avolio A., Avataneo V., Manca A., Cusato J., A. De Nicolò , Lucchini R., Keller F., Cantù M., Nutrients. 2020, 12(5). 10.3390/nu12051359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hastie C. E., Mackay D. F., Ho F., Celis‐Morales C. A., Katikireddi S. V., Niedzwiedz C. L., Jani B. D., Welsh P., Mair F. S., Gray S. R., O'Donnell C. A., Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ilie P. C., Stefanescu S., Smith L., Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32(7), 1195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jakovac H., Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 318, E589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Marik P. E., Kory P., Varon J., Med. Drug Discov. 2020. 10.1016/j.medidd.2020.100041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCartney D. M., Byrne D. G., Ir. Med. J. 2020, 113, 58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Panarese A., Shahini E., Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 51, 993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Merzon E., Tworowski D., Gorohovski A., et al. FEBS J. n/a. 10.1111/febs.15495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Slominski A. T., Janjetovic Z., Fuller B. E., Zmijewski M. A., Tuckey R. C., Nguyen M. N., Sweatman T., Li W., Zjawiony J., Miller D., Chen T. C., PLoS One 2010, 5, e9907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wang J., Slominski A., Tuckey R. C., Janjetovic Z., Kulkarni A., Chen J., Postlethwaite A. E., Miller D., Li W., Anticancer Res. 2012, 32, 739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Slominski A., Janjetovic Z., Tuckey R. C., Nguyen M. N., Bhattacharya K. G., Wang J., Li W., Jiao Y., Gu W., Brown M., Postlethwaite A. E., J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chen J., Wang J., Kim T. K., Tieu E. W., Tang E. K., Lin Z., Kovacic D., Miller D. D., Postlethwaite A., Tuckey R. C., Slominski A. T., Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 2153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Slominski A. T., Kim T. K., Janjetovic Z., Tuckey R. C., Bieniek R., Yue J., Li W., Chen J., Nguyen M. N., Tang E. K., Miller D., Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2011, 300, C526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shirvani A., Kalajian T. A., Song A., Holick M. F., Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Slominski A. T., Li W., Kim T. K., Semak I., Wang J., Zjawiony J. K., Tuckey R. C., J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2015, 151, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Holick M. F., J. Cell Biochem. 2003, 88, 296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Slominski A., Semak I., Wortsman J., Zjawiony J., Li W., Zbytek B., Tuckey R. C., FEBS J. 2006, 273, 2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Holick M. F., Binkley N. C., Bischoff‐Ferrari H. A., Gordon C. M., Hanley D. A., Heaney R. P., Murad M. H., Weaver C. M., J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Scott J. F., Das L. M., Ahsanuddin S., Qiu Y., Binko A. M., Traylor Z. P., Debanne S. M., Cooper K. D., Boxer R., Lu K. Q., J. Invest. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ebadi M., Montano‐Loza A. J., Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74(6), 856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Grant W. B., Baggerly C. A., Lahore H., Nutrients. 2020;12(6). 10.3390/nu12061620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Slominski A., Semak I., Zjawiony J., Wortsman J., Li W., Szczesniewski A., Tuckey R. C., FEBS J. 2005, 272, 4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Slominski A., Zjawiony J., Wortsman J., Semak I., Stewart J., Pisarchik A., Sweatman T., Marcos J., Dunbar C., Tuckey R., Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Holick M. F., Vitamin D., Mayo Clin. Proc. 2015, 90, 561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Comparison of the inhibition of inflammatory gene expression in epidermal keratinocytes by 20,23(OH)2D3 with 1,25(OH)2D3 based on retrospective analysis of microarray data deposited at the NCBI GEO (GSE117351). The values represent relative fold change in the gene expression