Abstract

Background

Ergothioneine (EGT) has a unique antioxidant ability and diverse beneficial effects on human health. But the content of EGT is very low in its natural producing organisms such as Mycobacterium smegmatis and mushrooms. Therefore, it is necessary to highly efficient heterologous production of EGT in food-grade yeasts such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Results

Two EGT biosynthetic genes were cloned from the mushroom Grifola frondosa and successfully heterologously expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118 strain in this study. By optimization of the fermentation conditions of the engineered strain S. cerevisiae EC1118, the 11.80 mg/L of EGT production was obtained. With daily addition of 1% glycerol to the culture medium in the fermentation process, the EGT production of the engineered strain S. cerevisiae EC1118 can reach up to 20.61 mg/L.

Conclusion

A successful EGT de novo biosynthetic system of S. cerevisiae containing only two genes from mushroom Grifola frondosa was developed in this study. This system provides promising prospects for the large scales production of EGT for human health.

Keywords: Ergothioneine, S. cerevisiae cell factory, Grifola frondosa, Heterologous expression

Background

Ergothioneine (EGT) is a derivative of hercynine with a sulfhydryl group attached to the second carbon atom on the imidazole ring and in the form of thione at pH 7. The EGT reduction potential energy is − 60 mV, which is higher than that (− 200 mV to − 320 mV) of other thiol structure antioxidant substances (such as glutathione and cysteine) and can effectively reduce auto-oxidation [1]. The situation showed that part of the product formed by the oxidation of EGT can be recombined back to EGT without a reducing agent, and the by-product contains sulfurous acid, which can be used as another reducing agent to counteract the intracellular oxidation state [2]. According to Cheah et al. [3], EGT accumulates at quite high levels in human tissues and cells, such as bone marrow, liver, kidney, semen, eyes and red blood cells. A group of investigators proposed that EGT may help relieve some of the symptoms associated with Cardiovascular disease [4], Crohn disease [5], and Alzheimer disease [6]. Cheah et al. [7] demonstrated that through oral administration of EGT, biomarkers of inflammation decreased and EGT was consider as a potential inhibitor for inflammation-related DNA halogenation [8]. Furthermore, EGT also reveals protective effect against hyperglycaemia-induced senescence [9] and smoke-induced oxidative damage [10]. Besides, some human cells, such as corneal endothelial [11], dermal fibroblasts [12] and keratinocytes [13] can be protected by EGT from oxidative attack. Additionally, EGT can chelate with Cu1+ [14] or Cu2+ [15] to be inert that prevent DNA and proteins form metal ions damage.

As a matter of fact, EGT cannot be synthesized in plants or animals and can only be synthesized by some bacteria and filamentous fungi, such as Mycobacterium smegmatis [16], Cyanobacteria [17], Neurospora crassa [18], and many mushrooms [19–21]. However, the EGT contents in original hosts are very low (range from 0 to 116 mg/100 g of dry weight in many species counting from Cumming et al. [22]) and the requirement for complex extraction or purification procedures of EGT from original producing organisms, restricting the commercially feasible in EGT production. There is need to develop a highly and efficiently method to increase EGT production, such as overexpressing the heterologous EGT biosynthetic genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Moreover, S. cerevisiae is a safe host (GRAS) which can be used in food additives and cosmetics industries [23].

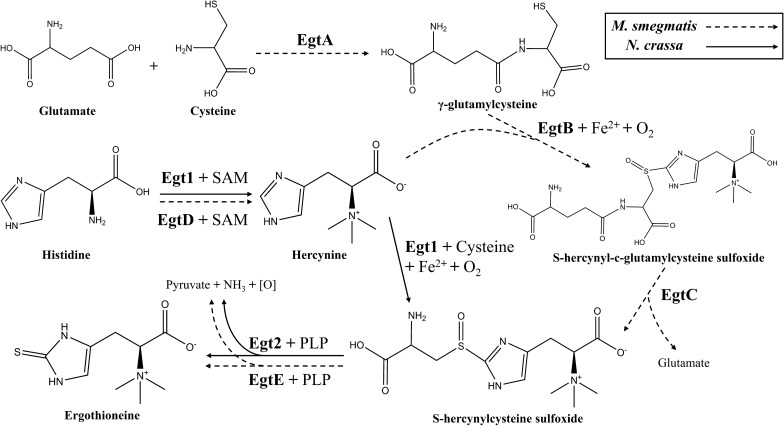

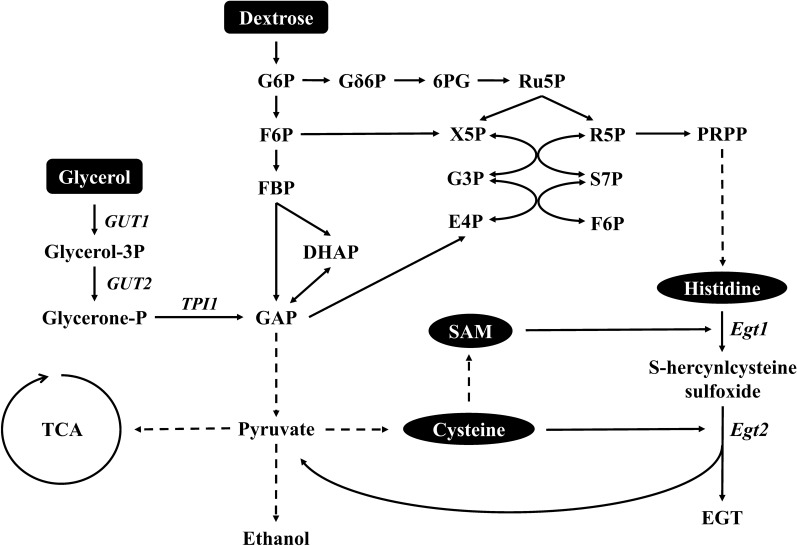

To date, two distinct biosynthetic pathways of EGT have been extensively studied (Fig. 1). One of them was first discovered in M. smegmatis containing the gene cluster egtABCDE [24], also similar in Methylobacterium species [25] and Streptomyces species [26]. On the other side, Hu et al. [27] firstly identified the EGT biosynthetic genes egt1 and egt2 which was homologous to egtBD and egtE respectively in the filamentous fungi N. crassa. Soon after, homologous for the genes egt1 and egt2 were also found in Schizosaccharomyces pombe [28]. Grifola frondosa is a kind of mushrooms that contains a variety of active substances and the contents of EGT are 0.29–1.11 mg/g (dry weight) [19, 20] which are higher than many other species reported. It is worth investigating the function of EGT biosynthetic genes in G. frondosa through heterologous expression system. S. cerevisiae is a eukaryotic expression host providing many kinds of modifications by organelles and is commonly used for natural products biosynthesis [29]. Therefore, heterologous expressing EGT biosynthetic genes from G. frondosa in S. cerevisiae could be a practicable way to produce EGT in large scale.

Fig. 1.

Two different pathways for EGT biosynthesis

In this study, the genes associated with EGT biosynthesis in the genome database of G. frondosa were analysed, and homologous genes were identified. We used RT-PCR to clone these genes and then overexpressed these two genes through pRS42K in S. cerevisiae. The results determined that heterologous overexpression in EGT synthesis only requested two genes from G. frondosa, which was simpler than five genes from Mycobacterium smegmatis [30] and three genes from Flammulina velutipes [31]. Higher EGT content was achieved to 20.61 mg/L by adjusting the carbon source and daily supply of glycerol in 168 h fermentation. Overall, de novo biosynthesis of EGT from glycerol in S. cerevisiae is a cost-effective and scalable strategy in commercial compared to chemosynthesis or extracting from other original organisms producing EGT.

Results

Genes cloned from Grifola frondosa

To clone the EGT biosynthetic genes from G. frondosa, the BLAST tool (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgito) was used to identify the corresponding sequence. Based on the gene sequences of N. crassa egt1 (NCU04343) and egt2 (NCU11365), we predicted that three hypothetical proteins, A0H81_08706 (with the S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM)-dependent methyltransferase domain), A0H81_08707 (with the 5-histidylcysteine sulfoxide synthase domain) and A0H81_07972 (with the pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent cysteine desulfurase domain), were involved in the EGT biosynthetic pathway. The Gfegt1 sequence (Additional file 1: Table S6) cloned by Gfegt1-F and Gfegt1-R was 2580 bp, and its protein consisted of 859 amino acids with a 34% homology to NcEgt1. Similarly, the Gfegt2 sequence (Additional file 1: Table S6) cloned by Gfegt2-F and Gfegt2-R was 1434 bp, and its protein consisted of 477 amino acids with a 33% identity to NcEgt2.

EGT production in recombinant S. cerevisiae

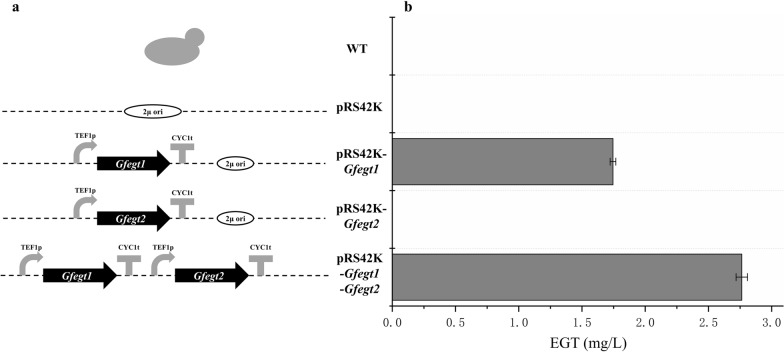

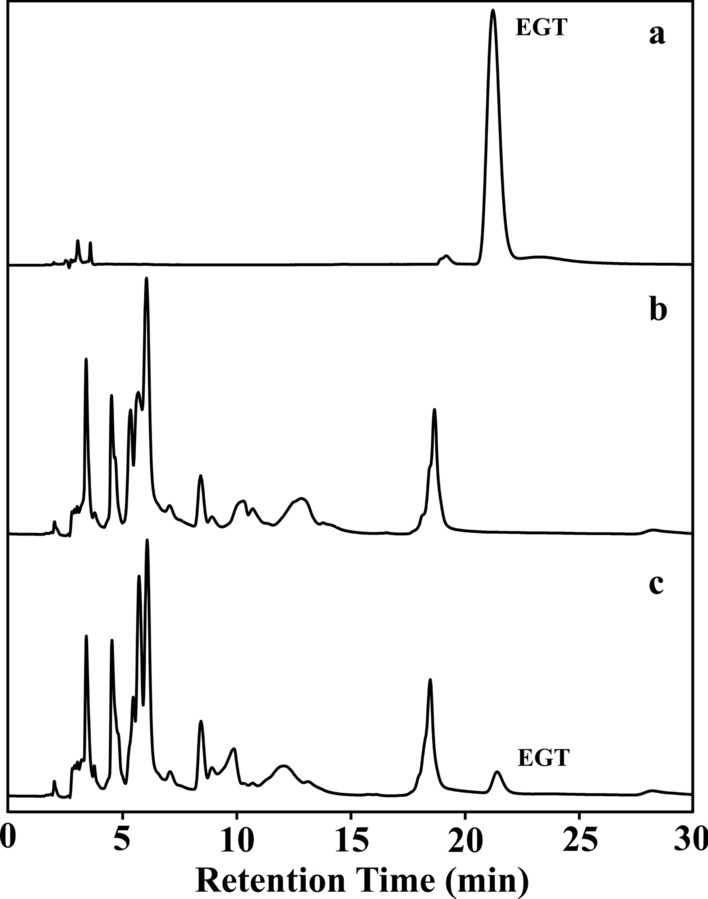

To examine the relative enzyme activity of GfEgt1 and GfEgt2, four recombinant yeasts (Fig. 2a) were constructed with plasmids pRS42K, pRS42K-Gfegt1, pRS42K-Gfegt2, and pRS42K-Gfegt1-Gfegt2, respectively. The EGT content appeared only in cell extraction and cannot be detected in culture medium. The HPLC results (Fig. 3) showed that the retention time of the EGT standards was approximately 21 min, and an extraction sample of strain expressing both GfEgt1 and GfEgt2 proteins displayed a corresponding peak at the same time, while the WT sample peak was absent. In the present study, we found that the strain expressing only GfEgt1 contained 1.74 ± 0.02 mg/L EGT, while no EGT was detected in the strain expressing only GfEgt2 (Fig. 2b; Additional file 1: Table S1). In addition, the strain with pRS42K-Gfegt1-Gfegt2 exhibited the ability to produce up to 2.76 ± 0.04 mg/L EGT which was 57% higher content than the strain expressing only GfEgt1. As a result, we consider that GfEgt1 and GfEgt2 are the key proteins for biosynthesizing EGT in G. frondosa.

Fig. 2.

EGT biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae containing different construction plasmids. a Different construction types of strains. b EGT extraction contents from different types of strains

Fig. 3.

HPLC separation and identification of EGT extracting from cells. a EGT Standards. b S. cerevisiae EC1118. c S. cerevisiae EC1118 carrying plasmid pRS42K-Gfegt1-Gfegt2

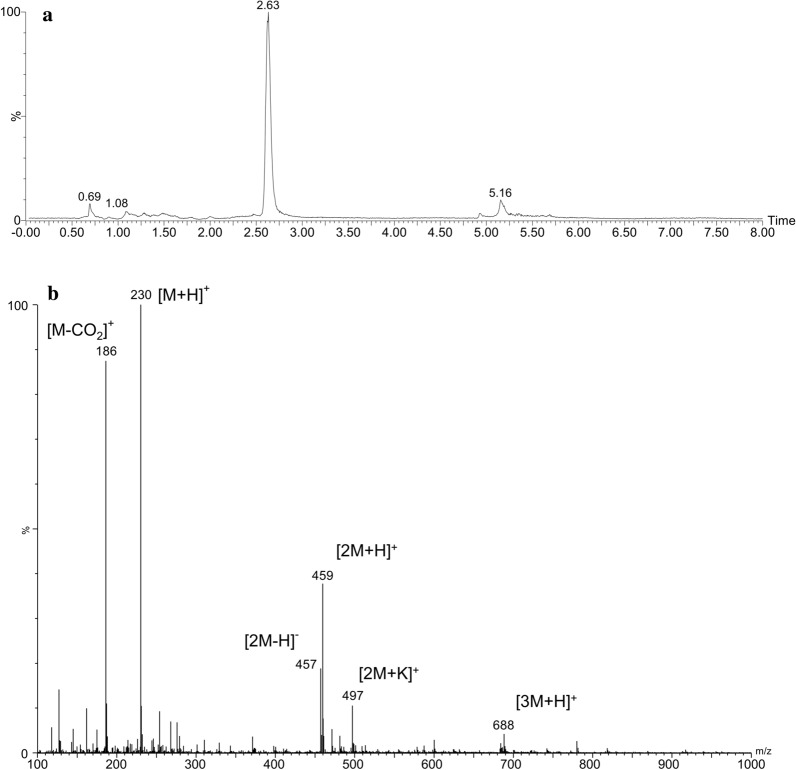

Identification of EGT

The UPLC chromatogram monitored at 262.7 nm and TOF MS ES+-selected ion monitored at m/z 230 confirmed that EGT was eluted at 2.63 min (Fig. 4a). The results of ESI–MS revealed a main molecular ion [M+H]+ of m/z 230.0971, which was consistent with the calculated exact molecular ion mass of 230.0963 (PPM = 3.5). Identification of the fragment ions were as follows: m/z 186 for 2-(2-mercapto-imidazol-5-yl)-N,N,N-trimethylethan-1-aminium (C8H16N3S+), which is the molecule of EGT lacking carboxyl group; m/z 497 for the sodium cluster ion [2M+K]+; and m/z 467, 459 and 688 for the cluster ions [2M−H]−, [2M+H]+ and [3M+H]+, respectively (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

UPLC-ESI–MS analysis of EGT extraction from recombinant strain. a Chromatogram of EGT monitored at 230 m/z. b Electrospray ionization mass spectrum of EGT obtained from extraction

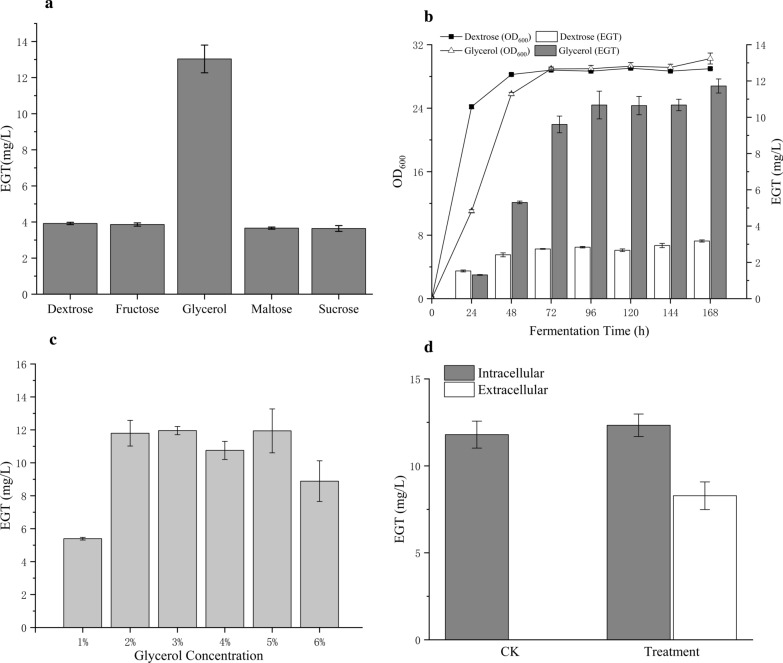

Carbon source of fermentation

Amino acids are the important reaction substances in the biosynthesis of EGT. Histidine is the starting material for the entire synthetic pathway. Cysteine provides sulfur atoms to EGT. Methionine is a precursor of SAM which is a source of methyl reactions. Different carbon sources lead to different amino acid contents and five different carbon sources (dextrose, fructose, glycerol, maltose, and sucrose) were used for the growth and amino acid production of yeasts in our study. We found that the EGT production from glycerol was 3.3-fold higher than that from dextrose (Fig. 5a; Additional file 1: Table S2). Subsequently, we analysed the fermentation conditions of dextrose and glycerol as carbon sources in each fermentation day (Fig. 5b; Additional file 1: Table S4). After activating the strains by YPD, we separated them into different carbon sources to ferment. The yeasts grown on dextrose displayed good vitality, while those grown on glycerol exhibited delayed cellular growth. However, both growths were in a plateau phase on the 3rd day and the EGT in vivo from glycerol exceeded that from dextrose at the 2nd day and reached a high level of approximately 10.68 ± 0.76 (mg/L) at the 4th day.

Fig. 5.

Optimization in EGT biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae with plasmid pRS42K-Gfegt1-Gfegt2. a Comparison of different carbon sources for EGT biosynthesis. b EGT contents and yeasts growth in each fermentation day. c Comparison of different glycerol concentration for EGT biosynthesis. d EGT biosynthesis through adding 1% glycerol in each fermentation day based on YPD medium (Treatment) and only based on YPD medium (CK)

In addition, different concentrations of glycerol were used to ferment the recombinant strain with pRS42K-Gfegt1-Gfegt2 (Fig. 5c; Additional file 1: Table S3). The analysing samples were mixed with intracellular and extracellular production. The results showed that fermentation using 1% glycerol as the only carbon source produced 5.39 ± 0.08 mg/L EGT, while 2–6% glycerol as the carbon source demonstrated a high yield of EGT, which was twofold higher than the former. However, there was no significant difference between the groups using 2% to 6% glycerol as the carbon source for fermentation. The higher concentration resulted in the inhibition of EGT synthesis. Considering the cost-effectiveness in manufacturing, 2% glycerol as the carbon source is a positive choice. Accordingly, the addition of all carbon sources at once was not feasible. We used YPG (2% glycerol) as the fermentation broth and added 1% glycerol each day for 7 days of fermentation. The result showed that the intracellular and extracellular EGT contents of treatment sample were 12.33 ± 0.65 mg/L and 8.28 ± 0.80 mg/L respectively, while EGT could not be detected from the extracellular in control sample. The total EGT content in treatment sample was about 20.61 mg/L (Fig. 5d; Additional file 1: Table S5). This phenomenon indicated that the suitable utilization of glycerol was a continuous progress.

Discussion

In this research, we studied and compared the genomic database of the mushroom G. frondosa using the N. crassa EGT synthase NcEgt1 and NcEgt2 and found that there were three unidentified proteins: the unidentified protein A0H81_08706 with medium homology to the first half of NcEgt1, the unidentified protein A0H81_08707 with medium homology to the latter half of NcEgt1, and the unidentified protein A0H81_07972 with medium homology to NcEgt2. Firstly, we speculated that these three proteins were involved in the EGT synthetic pathway in G. frondosa. Then, the target fragments for these three proteins were cloned. However, the amplified sequence for A0H81_08706 was not a complete ORF because there was one more base at position 937 in the gene sequence, which caused a subsequent frameshift mutation. Thus, The G. frondosa genome was extracted and used as a template to amplify the genes. It was found that this frameshift also existed in the genome, excluding the mutation that occurred in the process of transcription. Since the proteins A0H81_08706 and A0H81_08707 were adjacent, we regarded them as one protein and designed primers to subsequently clone a complete ORF. NcEgt1 from N. crassa possesses two domains which one is the same as EgtD and another is the same as EgtB in bacteria for the EGT synthetic enzymes, corresponding to proteins A0H81_08706 and A0H81_08707, respectively, in G. frondosa. However, the gene cloned from our laboratory strain had just one complete ORF containing two domains. It can be inferred that with the evolution of species and the gradually diversifying in modification function of the protein, the combination of these two enzymes to form only one enzyme contributes to the simplification of the synthesis step. Additionally, the sulfoxide synthase domain of NcEgt1 has been verified [27], but there was no methyltransferase activity research in the methyltransferase domain of NcEgt1. It is worthwhile to investigate whether the methyltransferase domain of GfEgt1 is functional or not in our coming research.

According to the results, with the different combined expression of EGT synthase, there was only GfEgt2 expression without EGT production. On the contrary, in the presence of only the GfEgt1 expression, EGT was produced. These results indicated that S. cerevisiae might have a protein with similar functions as that of Egt2 and lacked an enzyme that functions similarly to Egt1. Using NcEgt1, NcEgt2 and egtB, egtD, egtE as the source alignment, we searched the S. cerevisiae gene and protein database and found no genes or proteins homologous to these proteins. Comparing the two genes, SPBC1604.01 (homologous to NcEgt1) and SPBC660.12c (homologous to NcEgt2), which were related to the biosynthesis of EGT in S. Pombe [28], we found no results of SPBC1604.01, but there was a kynureninase catalysing transamination reaction in S. cerevisiae discovered by aligning it with SPBC660.12c. This enzyme consists part of cysteine desulfurase (SufS) domain and it is possible that its desulfurization function is not found yet. Similar to our results, only heterogenous expression of NcEgt1 in Aspergillus oryzae can also synthesize EGT [32]. Besides, Irani et al. [33] proposed the cleavage of the C-S was a main reaction between S-hercynylcysteine sulfoxide and PLP. It is predictable that two substances can react directly before binding to NcEgt1 or GfEgt1.

The reaction substrates and coenzymes participating in the EGT synthetic pathway can be synthesized by S. cerevisiae in vivo. SAM, the methyl donor for hercynine, was synthesized by S-adenosyl-l-methionine synthetase (EC 2.5.1.6) from methionine. The coenzyme of NcEgt2, PLP, is the active form of vitamin B6, produced from glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway. We used S. cerevisiae to express two EGT synthetases, and the fermentation by basic medium was free from additional enzymatic reaction materials. In our research, we tried to add amino acids to improve the production of EGT, but there was no apparent increase with the addition of cysteine and methionine. Besides, the addition of approximately 10 mM histidine slightly enhanced the EGT content by more than 4–5 mg/L. Considering industrial production applications, only using the basal medium was more economical. Interestingly, we found that the addition of more than 10 mM amino acids would decrease the EGT content, and over 30 mM obviously restrained the yeast growth. We suggest that the metabolism in cells is based on the carbon and nitrogen sources. Any addition of mM levels of foreign substances will change the metabolism pathway [34, 35].

The synthetic pathway of EGT involves multiple amino acid anabolic pathways, and different carbon sources result in different contents of the reaction substrate. Glycerol, when used as a carbon source, showed benefits over dextrose in producing EGT in S. cerevisiae. After glycerol enters yeast cells, it is first phosphorylated by glycerol kinase (encoded by GUT1) to glycerol-3P, followed by the reduction of FAD-dependent glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (encoded by GUT2) to glycerone-P. The other predicting pathways of dissimilation are the decomposition of glycerol by the ‘DHA pathway’ and the ‘GA pathway’ [36]. The ultimate products of these three different dissimilation pathways are only glycerone-P, which is then catalysed by triosephosphate isomerase (encoded by TPI1) to glyceraldehyde-3P (GAP), a precursor of glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Fig. 6). In contrast, if dextrose as a carbon source is assimilated by S. cerevisiae, its dissimilation is constructed by multiple metabolic pathways, which may reduce the synthesis effectiveness of the many important precursor substance in EGT synthesis (Fig. 6). Researches on the cultivation of yeast by glycerol have focused on the growth mechanism. Most wild-type and trial S. cerevisiae are difficult to grow in glycerol that is the carbon source medium [37]. Interestingly, Ho et al. [38] found that when glycerol was used as a carbon source, the strength of the promoters ALD4p and ADH2p associated with ethanol oxidation was reduced by 4 times compared with dextrose, meaning that the ethanol synthetic pathway declined and its upstream pathway obtained more sources. Besides, Strucko et al. [39] indicated that the change in the carbon source leads to the change of genome, in which the TCA cycle was decoupled from oxidative phosphorylation, thereby hampering ethanol utilization. Moreover, the change in TCA provides one NADH per C-mole when metabolized, and NADH may react with pyruvate, the accessory product from the reaction of GfEgt2, promoting the GfEgt2 catalytic rate. Specifically, we focused on cell growth after the recombinant strain was activated with YPD and fermented in glycerol or dextrose and found that yeast from glycerol medium grew slower than that grown from dextrose medium. This phenomenon was similar with diauxic shift, which reveal when fermentation yeasts reach a stationary phase after exhausting dextrose and start using by-products such as glycerol [40] as a carbon source to continue fermentation [41]. Our fermentation strategy utilized this phenomenon earlier and caused the expression of genes to change. For example, genes of energy metabolism, carbohydrate storage, gluconeogenesis, TCA and glyoxal cycles were highly upregulated [39]. When the expression levels of genes in the TCA cycle were upregulated, pyruvate, as the main source of the TCA cycle, was consumed in large quantities, thus promoting the rate of GfEgt2 enzymatic reactions and increasing the production of EGT.

Fig. 6.

Metabolic pathways involved in EGT biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae

Conclusion

Our research cloned EGT synthetic genes from the mushroom G. frondosa and explored the possibility of expressing these genes on S. cerevisiae. The results revealed that both of them had a predicted enzyme activity, and we regarded glycerol as a suitable carbon source to produce EGT up to approximately 20.61 mg/L after 168 h optimized fermentation. There were only two genes we chose to construct for the EGT biosynthesis strain, which were more simplified than the five genes reported [30]. The empirical findings in this study provide a S. cerevisiae cell factory in producing EGT and a new understanding of EGT biosynthesis in mushroom field.

Materials and methods

Strains and plasmids

The mushroom G. frondosa was obtained from Beijing Lucky Mushroom Garden (China) and provided a source of cloning the EGT biosynthetic genes. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae EC1118 strain is a commercial wine yeast strain that was isolated, studied and selected from Champagne fermentations and then produced and commercialized by Lallemand (Ontario, Canada). Escherichia coli DH5a (Takara, Japan) was used for cloning host. The cloning vector was pMD18T (Takara, Japan) with ampicillin resistance, and the expression vectors were constructed based on the pRS42K shuttle vector with geneticin resistance, which was presented by Professor Christof Taxis and Professor Michael Knop from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory [42].

Cloning Gfegt1 and Gfegt2

The mushroom G. frondosa was cultured at 25 °C with 150 rpm shaking in PDB (20% potato, 2% dextrose, 0.15% MgSO4·7H2O, and 0.3% KH2PO4). Once the jar was fully colonized by the fungus ball, mycelia were collected from the liquid culture by filtering. For the extraction of fungal RNA, the mycelia were disrupted by grinding in liquid nitrogen, and then total RNA was extracted from the powder using TRNzol reagent (Tiangen, China). The TransScript Kit (TransGen, China) was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA from total RNA of G. frondosa. The Kod-Fx enzyme (Toyobo, Japan) was used for the accurate PCR amplification of DNA. The cloned DNA sequences were named Gfegt1 and Gfegt2. The entire Gfegt1 open reading frame (ORF) was amplified with the forward primer, Gfegt1-F, 5′-atgtcgaccctccaggatttcttc-3′ and the reverse primer, Gfegt1-R, 5′-ttacacatcatacgcaatccgagcg-3′. The entire Gfegt2 ORF was amplified with the forward primer, Gfegt2-F, 5′-atgacggccatagatctaggtgc-3′ and the reverse primer, Gfegt2-R, 5′-ctaattacgcttctctgcgagaagg-3′. The PCR products were purified, and an A base was added at the end of the 3′ fragment. Then, the pMD18T plasmid was connected and translated into E. coli DH5α for sequencing and preservation.

Construction of recombinant S. cerevisiae EC1118

pRS42K was the basis of the expression vector. pRS42K was double digested with SalI and EcoRI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and recombined with the promotor TEF1p, terminator CYC1t, Gfegt1, and Gfegt2 by using the ClonExpress Ultra One Step Cloning Kit (Vazyme, China). The plasmids pRS42K (control), pRS42K-Gfegt1 (contain Gfegt1), pRS42K-Gfegt2 (contain Gfegt2), and pRS42K-Gfegt1-Gfegt2 (contain Gfegt1 and Gfegt2) (Fig. 2a) were transformed to S. cerevisiae EC1118 by the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method [43]. The growth of recombinant strains was tested on YPD plates (2% peptone, 2% dextrose, and 1% yeast extract) with the addition of 200 mg/L G418. The Kod-Fx enzyme (Toyobo, Japan) was used for the PCR analysis.

Fermentation methods

Recombinant S. cerevisiae EC1118 was activated by YPD broths with 200 mg/L G418 and cultured overnight at 30 °C and 200 rpm. These cells were washed with ddH2O and then adjusted to OD600 = 2.0. The strains were inoculated (1% v/v) into a new fermentation medium without antibiotics for subsequent multiple fermentations. Different carbon source fermentations used YPX (Y for 1% yeast extract, P for 2% peptone, and X for 2% dextrose, 2% fructose, 2% glycerol, 2% maltose, or 2% sucrose). Different concentrations (1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, 5%, and 6%) of glycerol fermentation used YPG (Y for 1% yeast extract, P for 2% peptone, and G for glycerol). Daily supply of 1% glycerol sample means directly adding 1% glycerol (based on YPG volume) into YPG medium in each fermentation day and the control sample means only ferment in YPG (Y for 1% yeast extract, P for 2% peptone, and G for 2% glycerol) without any addition.

After fermentation, the content was centrifuged at 3000×g for 5 min at 25 °C to separate the culture and yeast, and then the yeast was incubated with 1 ml 50% ethanol at 50 °C for 30 min. The supernatant from the culture and cell extraction from the yeast incubation were collected and filtered through a 0.22 µm filter and then analysed by HPLC.

HPLC analysis of ergothioneine

HPLC analyses of the above supernatants were performed on a Shimadzu LC-2030 HPLC system (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with an Ultimate® HILIC Amphion II column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm; Welch, China) with a matching guard column. For the EGT detection, 20 μL samples were separated with 20% water/80% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min at 30 °C. EGT was detected at 254 nm at a peak retention time of approximately 21.0 min.

UPLC-ESI–MS analysis of ergothioneine

Mass spectrometry detection was performed by a High Definition Mass Spectrometer (Synapt G2-Si, Waters, USA). The chromatographic analysis was performed in an ACQUITY UPLC System (Waters). An aliquot of 1 μL of sample solution was injected into an ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters) at 35 °C, and the flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. The optimal mobile phase consisted of a linear gradient system of (A) acetonitrile and (B) water, 0–4.0 min, 80% A; 4.0–4.5 min, 80–60% A; 4.5–7.0 min, 60% A; 7.0–7.2 min, 60–80% A; and 7.2–10.0 min, 80% A. The optimized analysis conditions were as follows: source temperature. 120 °C; desolvation gas temperature, 350 °C; cone gas flow, 40 L/h; desolvation gas flow, 1000 L/h; and capillary voltage, 2.3 kV.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- EGT

Ergothioneine

- GRAS

Generally recognized as safe

- ORF

Open reading frame

- SAM

S-adenosyl-l-methionine

- PLP

Pyridoxal phosphate

- TCA

Tricarboxylic acid

Authors’ contributions

YHY, LQG, and JFL designed the experiments; YHY, HLL and HYL performed the experiments; YHY analyzed data and wrote the manuscript; HYP contributed to edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Realm R&D Program of Guangdong Province (Grant Nos. 2018B020205003, 2018B020205001) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 31772373, 31572178).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the additional file.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Li-Qiong Guo, Email: guolq@scau.edu.cn.

Jun-Fang Lin, Email: linjf@scau.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12934-020-01421-1.

References

- 1.Hartman PE. [32] Ergothioneine as antioxidant. In: Methods in enzymology, vol. 186. Academic Press; 1990. p. 310–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Song H, Hu W, Naowarojna N, Her AS, Wang S, Desai R, Qin L, Chen X, Liu P. Mechanistic studies of a novel C-S lyase in ergothioneine biosynthesis: the involvement of a sulfenic acid intermediate. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11870. doi: 10.1038/srep11870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheah IK, Halliwell B. Ergothioneine; antioxidant potential, physiological function and role in disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822(5):784–793. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith E, Ottosson F, Hellstrand S, Ericson U, Orho-Melander M, Fernandez C, Melander O. Ergothioneine is associated with reduced mortality and decreased risk of cardiovascular disease. Heart. 2020;106(9):691–697. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-315485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai Y, Xue J, Liu CW, Gao B, Chi L, Tu P, Lu K, Ru H. Serum metabolomics identifies altered bioenergetics, signaling cascades in parallel with exposome markers in Crohn’s disease. Molecules. 2019;24(3):449. doi: 10.3390/molecules24030449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheah IK, Feng L, Tang RMY, Lim KHC, Halliwell B. Ergothioneine levels in an elderly population decrease with age and incidence of cognitive decline; a risk factor for neurodegeneration? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478(1):162–167. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheah IK, Tang RM, Yew TS, Lim KH, Halliwell B. Administration of pure ergothioneine to healthy human subjects: uptake, metabolism, and effects on biomarkers of oxidative damage and inflammation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2017;26(5):193–206. doi: 10.1089/ars.2016.6778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asahi T, Wu X, Shimoda H, Hisaka S, Harada E, Kanno T, Nakamura Y, Kato Y, Osawa T. A mushroom-derived amino acid, ergothioneine, is a potential inhibitor of inflammation-related DNA halogenation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2016;80(2):313–317. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2015.1083396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Onofrio N, Servillo L, Giovane A, Casale R, Vitiello M, Marfella R, Paolisso G, Balestrieri ML. Ergothioneine oxidation in the protection against high-glucose induced endothelial senescence: involvement of SIRT1 and SIRT6. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;96:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nickel S, Selo M, Clerkin C, Talbot B, Walsh J, Nakamichi N, Kato Y, Reynolds P, Lewis J, Ehrhardt C. Ergothioneine protects lung epithelial cells from tobacco smoke-induced oxidative damage in vitro and in vivo. In: D96 Damaging Effects Of Inhaled Particulates. American Thoracic Society; 2016. p. A7514.

- 11.Kim EC, Toyono T, Berlinicke CA, Zack DJ, Jurkunas U, Usui T, Jun AS. Screening and characterization of drugs that protect corneal endothelial cells against unfolded protein response and oxidative stress. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017;58(2):892–900. doi: 10.1167/iovs.16-20147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hseu YC, Vudhya Gowrisankar Y, Chen XZ, Yang YC, Yang HL. The antiaging activity of ergothioneine in uva-irradiated human dermal fibroblasts via the inhibition of the AP-1 pathway and the activation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidant genes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:2576823. doi: 10.1155/2020/2576823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hseu YC, Lo HW, Korivi M, Tsai YC, Tang MJ, Yang HL. Dermato-protective properties of ergothioneine through induction of Nrf2/ARE-mediated antioxidant genes in UVA-irradiated Human keratinocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;86:102–117. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rai RK, Chalana A, Karri R, Das R, Kumar B, Roy G. Role of hydrogen bonding by thiones in protecting biomolecules from copper(I)-mediated oxidative damage. Inorg Chem. 2019;58(10):6628–6638. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b03212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu BZ, Mao L, Fan RM, Zhu JG, Zhang YN, Wang J, Kalyanaraman B, Frei B. Ergothioneine prevents copper-induced oxidative damage to DNA and protein by forming a redox-inactive ergothioneine-copper complex. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24(1):30–34. doi: 10.1021/tx100214t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genghof DS, Van Damme O. Biosynthesis of ergothioneine from endogenous hercynine in Mycobacterium smegmatis. J Bacteriol. 1968;95(2):340–344. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.2.340-344.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfeiffer C, Bauer T, Surek B, Schomig E, Grundemann D. Cyanobacteria produce high levels of ergothioneine. Food Chem. 2011;129(4):1766–1769. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Genghof DS. Biosynthesis of ergothioneine and hercynine by fungi and Actinomycetales. J Bacteriol. 1970;103(2):475–478. doi: 10.1128/jb.103.2.475-478.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S-Y, Ho K-J, Hsieh Y-J, Wang L-T, Mau J-L. Contents of lovastatin, γ-aminobutyric acid and ergothioneine in mushroom fruiting bodies and mycelia. Lwt. 2012;47(2):274–278. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalaras MD, Richie JP, Calcagnotto A, Beelman RB. Mushrooms: a rich source of the antioxidants ergothioneine and glutathione. Food Chem. 2017;233:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.04.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dubost NJ, Beelman RB, Peterson D, Royse DJ. Identification and quantification of ergothioneine in cultivated mushrooms by liquid chromatography-mass spectroscopy. Int J Med Mushrooms. 2006;8(3):215–222. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cumming BM, Chinta KC, Reddy VP, Steyn AJC. Role of ergothioneine in microbial physiology and pathogenesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2018;28(6):431–444. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Guan NZ, Li JH, Shin HD, Du GC, Chen J. Development of GRAS strains for nutraceutical production using systems and synthetic biology approaches: advances and prospects. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2017;37(2):139–150. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2015.1121461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seebeck FP. In vitro reconstitution of mycobacterial ergothioneine biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132(19):6632–6633. doi: 10.1021/ja101721e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alamgir KM, Masuda S, Fujitani Y, Fukuda F, Tani A. Production of ergothioneine by Methylobacterium species. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1185. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima S, Satoh Y, Yanashima K, Matsui T, Dairi T. Ergothioneine protects Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) from oxidative stresses. J Biosci Bioeng. 2015;120(3):294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2015.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu W, Song H, Sae Her A, Bak DW, Naowarojna N, Elliott SJ, Qin L, Chen X, Liu P. Bioinformatic and biochemical characterizations of C–S bond formation and cleavage enzymes in the fungus Neurospora crassa ergothioneine biosynthetic pathway. Org Lett. 2014;16(20):5382–5385. doi: 10.1021/ol502596z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pluskal T, Ueno M, Yanagida M. Genetic and metabolomic dissection of the ergothioneine and selenoneine biosynthetic pathway in the fission yeast, S. pombe, and construction of an overproduction system. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e97774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krivoruchko A, Nielsen J. Production of natural products through metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2015;35:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osawa R, Kamide T, Satoh Y, Kawano Y, Ohtsu I, Dairi T. Heterologous and high production of ergothioneine in Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(5):1191–1196. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b04924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X, Lin S, Lin J, Wang Y, Lin J-F, Guo L. The biosynthetic pathway of ergothioneine in culinary-medicinal winter mushroom, Flammulina velutipes (Agaricomycetes) Int J Med Mushrooms. 2020;22(2):171–81. doi: 10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.2020033826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takusagawa S, Satoh Y, Ohtsu I, Dairi T. Ergothioneine production with Aspergillus oryzae. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2019;83(1):181–184. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2018.1527210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Irani S, Naowarojna N, Tang Y, Kathuria KR, Wang S, Dhembi A, Lee N, Yan W, Lyu H, Costello CE, et al. Snapshots of C–S cleavage in Egt2 reveals substrate specificity and reaction mechanism. Cell Chem Biol. 2018;25(5):519–529.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2018.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ljungdahl PO, Daignan-Fornier B. Regulation of amino acid, nucleotide, and phosphate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2012;190(3):885–929. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.133306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hinnebusch AG. Mechanisms of gene regulation in the general control of amino acid biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52(2):248–273. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.2.248-273.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klein M, Swinnen S, Thevelein JM, Nevoigt E. Glycerol metabolism and transport in yeast and fungi: established knowledge and ambiguities. Environ Microbiol. 2017;19(3):878–893. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swinnen S, Klein M, Carrillo M, McInnes J, Nguyen HTT, Nevoigt E. Re-evaluation of glycerol utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: characterization of an isolate that grows on glycerol without supporting supplements. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2013;6(1):157. doi: 10.1186/1754-6834-6-157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ho PW, Klein M, Futschik M, Nevoigt E. Glycerol positive promoters for tailored metabolic engineering of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018;18(3):foy019. doi: 10.1093/femsyr/foy019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strucko T, Zirngibl K, Pereira F, Kafkia E, Mohamed ET, Rettel M, Stein F, Feist AM, Jouhten P, Patil KR, Forster J. Laboratory evolution reveals regulatory and metabolic trade-offs of glycerol utilization in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Metab Eng. 2018;47:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang ZX, Zhuge J, Fang H, Prior BA. Glycerol production by microbial fermentation: a review. Biotechnol Adv. 2001;19(3):201–223. doi: 10.1016/s0734-9750(01)00060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Puig S, Pérez-Ortín JE. Stress response and expression patterns in wine fermentations of yeast genes induced at the diauxic shift. Yeast. 2000;16(2):139–148. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(20000130)16:2<139::AID-YEA512>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taxis C, Knop M. System of centromeric, episomal, and integrative vectors based on drug resistance markers for Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechniques. 2006;40(1):73–78. doi: 10.2144/000112040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gietz RD, Schiestl RH. Large-scale high-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protocols. 2007;2(1):38–41. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and the additional file.