Abstract

Background

The Oncotype DX 21-gene Recurrence Score is a genomic-based algorithm that guides adjuvant chemotherapy treatment decisions for women with early-stage, oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive breast cancer. However, there are age-related differences in chemotherapy benefit for women with intermediate Oncotype DX Recurrence Scores that are not well understood. Menstrual cycling in younger women is associated with hormonal fluctuations that might affect the expression of genomic predictive biomarkers and alter Recurrence Scores. Here, we use paired human breast cancer samples to demonstrate that the clinically employed Oncotype DX algorithm is critically affected by patient age.

Methods

RNA was extracted from 25 pairs of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded, invasive ER-positive breast cancer samples that had been collected approximately 2 weeks apart. A 21-gene signature analogous to the Oncotype DX platform was assessed through quantitative real-time PCR, and experimental recurrence scores were calculated using the Oncotype DX algorithm.

Results

There was a significant inverse association between patient age and discordance in the recurrence score. For every 1-year decrease in age, discordance in recurrence scores between paired samples increased by 0.08 units (95% CI − 0.14, − 0.01; p = 0.017). Discordance in recurrence scores for women under the age of 50 was driven primarily by proliferation- and HER2-associated genes.

Conclusion

The Oncotype DX 21-gene Recurrence Score algorithm is critically affected by patient age. These findings emphasise the need for the consideration of patient age, particularly for women younger than 50, in the development and application of genomic-based algorithms for breast cancer care.

Keywords: Premenopausal breast cancer, Predictive biomarkers, Age, Menstrual cycle, Genomics

Introduction

Emerging in the clinic are new assays that utilise gene-expression profiling to provide an intrinsic, molecular portrait of an individual breast cancer. The expression of a panel of biomarkers is quantified in a tumour sample, and these are combined in an algorithm to predict the risk of disease recurrence and treatment response. This genomic approach promises improved treatment decision-making capabilities compared to traditional protein-based methods and is part of a new era of genomic-based precision medicine [1, 2]. Nevertheless, caution in the adoption of algorithms to guide health decisions is required. Bias against under-represented groups can occur if not explicitly accounted for, and utility of the assay may not be directly transferable to patient groups not included in its development [3, 4].

A leading genomic biomarker assay, Oncotype DX, quantifies a panel of 21 genes and combines them into an algorithm to produce a Recurrence Score that predicts the likely benefit of the addition of chemotherapy to endocrine treatment [5–10]. The Oncotype DX assay is recommended in international guidelines to guide adjuvant chemotherapy treatment decisions for women with early-stage, oestrogen receptor (ER)-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer [11–14]. The Oncotype DX assay is available to both premenopausal and postmenopausal women to assist treatment decision-making, and use of the assay results in a net reduction in chemotherapy use [15]. However, Oncotype DX was developed and validated predominantly in postmenopausal women [16], and age-related differences in chemotherapy benefit have been identified [10].

The TAILORx study [10] incorporated data from 9719 women with breast cancer, reporting that for women over the age of 50 years with Recurrence Scores less than 26 (n = 4495), endocrine therapy alone was not inferior to chemo-endocrine therapy in terms of disease-free and overall survival. However, women under the age of 50 with Recurrence Scores between 16 and 25 (n = 2216) still derived some benefit from chemotherapy. When clinical information was integrated with Oncotype DX Recurrence Scores, the prediction of which premenopausal patients would receive a substantial benefit from chemotherapy was not improved [17]. The biological basis of this age-related difference in chemotherapy benefit for women with intermediate Recurrence Scores is not well defined.

In premenopausal women, hormone receptor protein expression fluctuates throughout the menstrual cycle in response to fluctuating concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone and this is associated with downstream changes in the expression of a number of genes which are part of the Oncotype DX signature including PGR, MKI67, CCNB1, BIRC5 and MYBL2 [18–23]. Therefore, changes in gene expression with menstrual cycle stage could affect Oncotype DX Recurrence Scores. Indeed, an in vitro study suggests that the co-treatment of breast cancer cell lines with oestrogen and progesterone increases Oncotype DX Recurrence Scores, compared to oestrogen treatment alone [24].

In this study, we propose that menstrual cycling in premenopausal women affects the Oncotype DX 21-gene algorithm. We conducted a retrospective study on paired human ER-positive breast cancer samples (the biopsy and definitive surgery of the tumour) to investigate how patient age affects variability in a 21-gene experimental recurrence score, analogous to the Oncotype DX Recurrence Score, within the same tumour. If menstrual cycling affects Oncotype DX Recurrence Scores, it is hypothesised there would be increased discordance in recurrence scores between paired samples collected from younger women compared to non-cycling older women.

Methods

Human breast cancer sample collection

Ethics approval was obtained from The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number Q20170106), and informed consent was obtained from study participants. Paired formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast cancer samples were retrospectively collected from women diagnosed with invasive, ER-positive breast cancer. Patients presenting with benign breast disease or who had received any neoadjuvant therapy were excluded from the study.

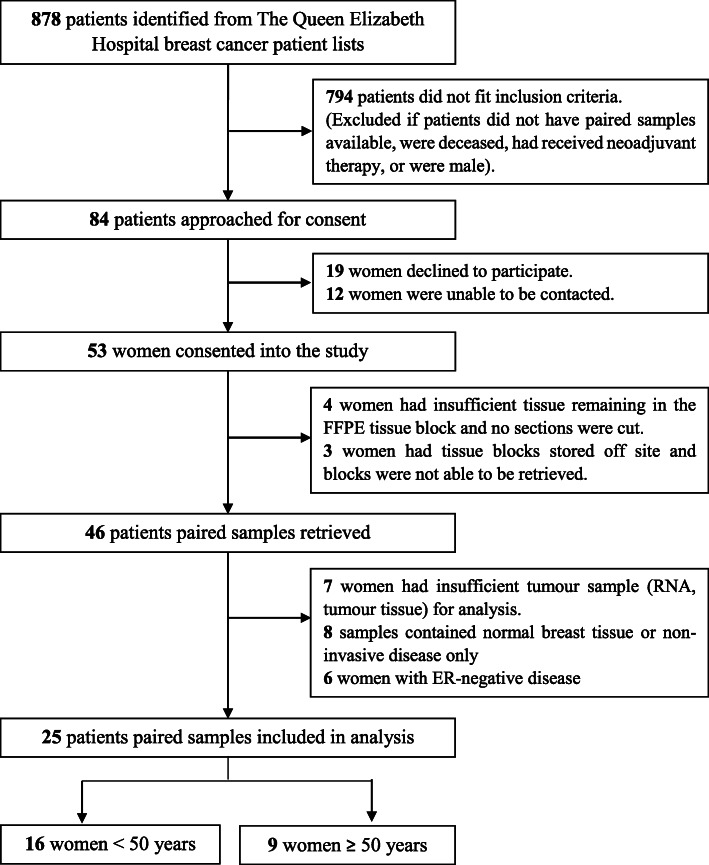

Patients were identified from a list of 878 breast cancer patients who had been referred to The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Oncology Unit between 2000 and 2015. Patients were ineligible if they did not have two samples of the same tumour (i.e. the biopsy and definitive surgery of the tumour) available, were deceased, had received neoadjuvant therapy or were male. Following review for eligibility, consent was obtained and FFPE blocks were retrieved and then assessed by haematoxylin and eosin staining to confirm the presence of invasive breast cancer in each sample. All samples that met these criteria were used in the final analysis, with 25 pairs of breast cancer samples meeting these criteria. The process for identifying and recruiting patients is highlighted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart showing patient recruitment. Potential patients for inclusion in the study were identified from The Queen Elizabeth Hospital breast cancer patient lists. Of the 878 patients initially identified, 25 women were included in the study; 16 women aged under 50 and 9 women aged over 50

Haematoxylin and eosin staining

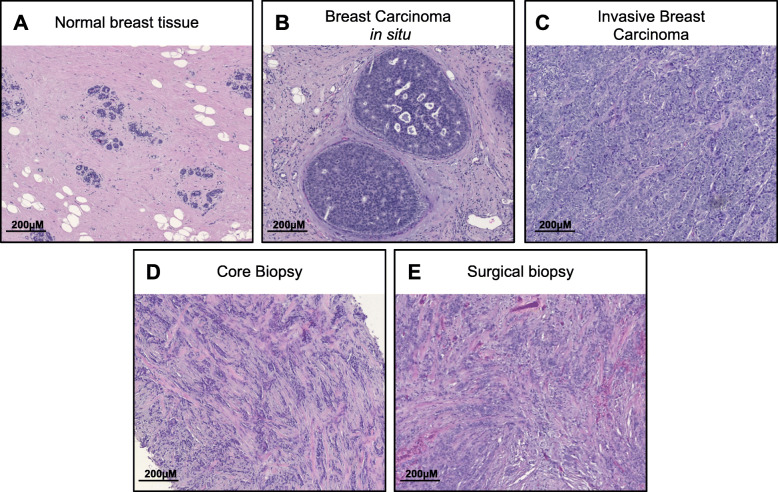

To confirm the presence of invasive breast cancer in the tissue sample, haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed on 5-μM paraffin-embedded sections. Sections were dewaxed in xylene and subsequently passed through 100%, 90%, 70% and 50% ethanol for rehydration. Slides were stained with haematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich) and counterstained with eosin (Sigma-Aldrich), prior to dehydrating and mounting with Entellan mounting medium. H&E-stained FFPE breast cancer samples were assessed by a pathologist to confirm the presence of malignant disease prior to RNA extraction. Examples of haematoxylin- and eosin-stained tissue sections are presented in Fig. 2. Other characteristics of the tumour were obtained from pathological reports completed at the time of diagnosis.

Fig. 2.

Haematoxylin and eosin stains of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections collected from breast cancer patients. FFPE tissue blocks were retrieved from 46 patients, and haematoxylin and eosin stains were performed to confirm the presence of malignant breast disease. Examples of a normal breast tissue, b carcinoma in situ and c invasive carcinoma. Samples that did not contain invasive disease were excluded from analysis. d, e Haematoxylin and eosin stain of a core biopsy and corresponding surgically excised tumour from a patient with a grade 3 invasive ductal carcinoma. Bars represent 200 μM

RNA extraction and complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from 6 × 10 μm thick FFPE breast cancer tissue sections using the PureLink FFPE RNA Isolation kit (Invitrogen). cDNA was reverse transcribed from approximately 250 ng of RNA using SuperScript IV VILO with ezDNase Enzyme (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Custom designed 384-well TaqMan array cards (ThermoFisher) were used to measure gene expression in FFPE breast cancer samples. Primer sequences were designed by ThermoFisher. Array cards were loaded with 100 μL of 1:1 mix of cDNA and TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and run using a QuantStudio12K Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems), as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression of each gene was measured in duplicate.

Calculation of 21-gene experimental recurrence scores

Normalised gene expression measurements were calculated as Δ CT = CT (mean of five reference genes) – CT (gene of interest) + 10. A 1-unit increase in reference-normalised expression measurements reflects a doubling of RNA. Experimental recurrence scores were calculated from reference-normalised gene expression, using the Oncotype DX 21-gene Recurrence Score algorithm, as described below.

To calculate experimental recurrence scores, 21-gene group scores were first calculated using normalised gene expression measurements:

The unscaled experimental recurrence score (RSu) was calculated from the above group scores:

The scaled experimental recurrence score (RS) was then calculated from the unscaled recurrence score:

Results

Patient characteristics

Twenty-five patients with ER-positive, invasive breast cancer were included in the analysis. Hormone receptor status was obtained from pathology reports completed during the routine breast cancer diagnosis. Patient and tumour characteristics are detailed in Table 1. Paired samples were collected from the same tumour at different times; twenty-two women had paired core needle biopsies and corresponding surgical excisions, while three women had paired surgical excisions and corresponding re-excisions with residual disease. Sample 1 was defined as the earlier collected sample, with sample 2 as the corresponding later collected pair. The dates of sample collection were obtained from electronic medical records. Paired samples were collected an average of 18 days apart, and in the absence of any intervention.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Total number | 25 |

| Median age at diagnosis | 48 |

| Years; range | 36–77 |

| Median days between samples | 19 |

| Days; range | 6–42 |

| Tumour type | |

| IDC | 18 (72) |

| ILC | 6 (24) |

| Other | 1 (3) |

| Tumour grade | |

| 1 | 6 (24) |

| 2 | 13 (52) |

| 3 | 5 (20) |

| Unknown | 1 (4) |

| Tumour size | |

| ≤ 10 mm | 2 (8) |

| 11–20 mm | 8 (32) |

| 21–50 mm | 8 (32) |

| > 50 mm | 6 (24) |

| Unknown | 1 (4) |

| Lymph node status | |

| Positive | 13 (52) |

| Negative | 11 (44) |

| Unknown | 1 (4) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |

| Present | 18 (72) |

| Absent | 7 (28) |

Correlation in the 21-gene signature and experimental recurrence scores between paired breast cancer samples

Details of patient menopausal status or menstrual cycle stage at the time of tissue collection are not routinely reported, and this information was not available for this research. An arbitrary age of 50 is often used to define menopausal status in clinical studies [25]. However, as the perimenopausal period occurs over a highly variable time frame, lasts up to 10 years and is characterised by disrupted ovarian hormone secretion and irregular menses, the initial statistical analysis was conducted using age as a continuous variable.

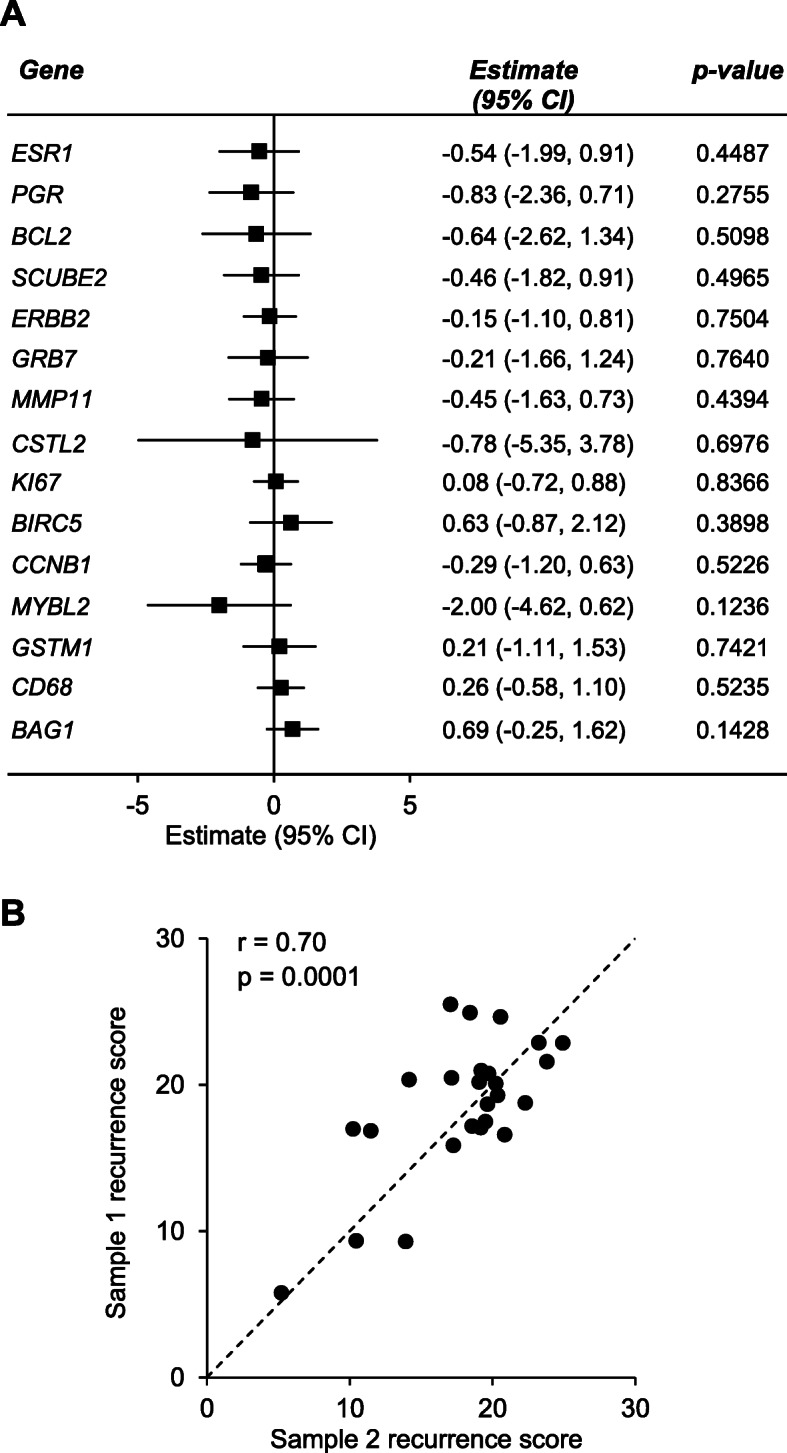

Samples collected from the same breast cancer on different days are anticipated to show some variability in gene expression due to extrinsic factors such as the precise part of the tumour biopsied as well as differences in tumour fixation and processing [26, 27]. This variability is expected to be similar between premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Indeed, we found no significant differences between samples 1 and 2 in the expression of the 21 genes and patient age did not influence the magnitude of change in gene expression between paired samples when assessed using linear mixed-effect models adjusted for repeated measurements (p > 0.05; Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Agreement in the 21-gene signature and experimental recurrence scores between paired breast cancer samples. Paired breast cancer samples were collected from women with invasive, ER-positive breast cancer (n = 25). The 21-gene signature was assessed through real-time PCR. a Forest plot showing concordance in gene expression between sample 1 and sample 2, for the genes which comprise the Oncotype DX 21-gene signature. To determine if gene expression varied significantly between paired samples, statistical significance was assessed using linear mixed-effect models adjusted for multiple comparisons. No data were statistically significant (p > 0.05). b Correlation in experimental recurrence scores between paired samples. Recurrence scores were calculated from reference-normalised gene expression as described in the “Methods” section. Sample 1 corresponds to the first collected sample, presented against its corresponding later collected pair, sample 2. The dashed line represents perfect correlation, where deviation from the line reflects discordance between paired samples. Spearman’s correlations and p values are presented

From this reference-normalised gene expression data, a 21-gene experimental recurrence score was calculated for each sample. This recurrence score is analogous to the Oncotype DX Recurrence Score. The recurrence score of sample 1 significantly correlated with the recurrence score of sample 2 (Spearman’s correlation coefficient r = 0.70, p = 0.0001; Fig. 3b). Together, these findings confirm that variability in gene expression due to extrinsic factors was similar between premenopausal and postmenopausal women and that the two samples that comprise each pair are related in their gene expression signature.

Experimental recurrence scores are more variable in paired samples collected from younger women and are driven by variable expression of Proliferation and HER2 group genes

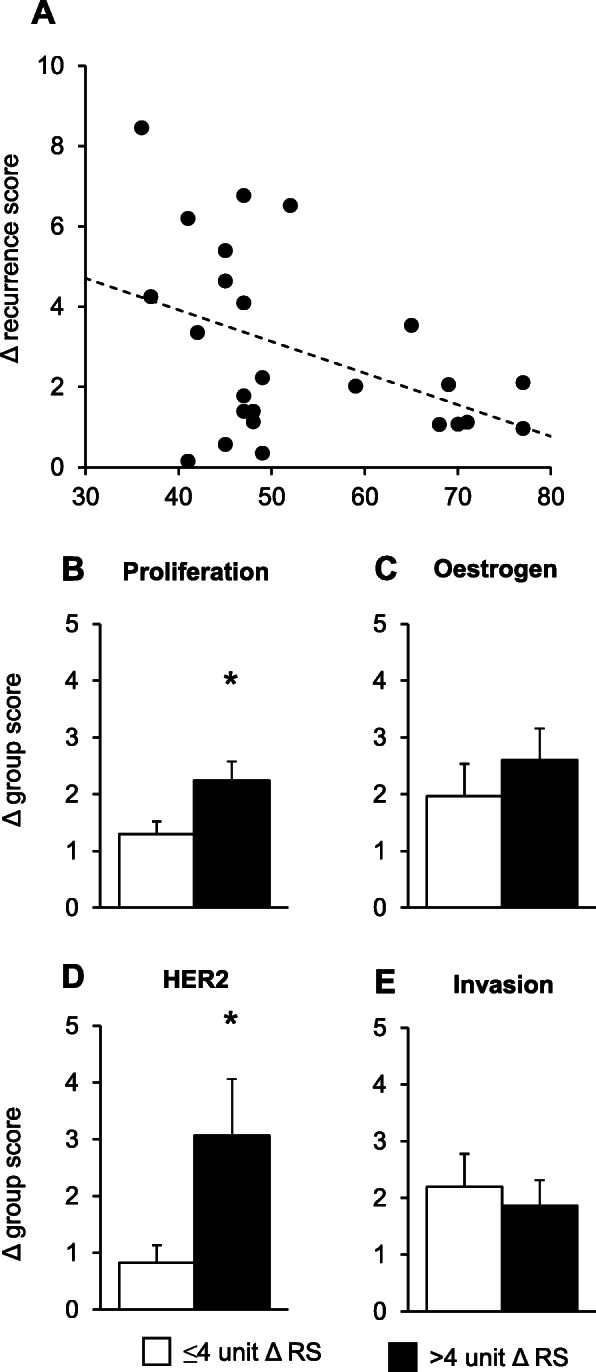

To quantify discordances in recurrence scores between paired breast cancer samples, the absolute difference in recurrence score between sample 1 and sample 2 was calculated. Discordance was analysed with age as a continuous variable. There was a significant inverse association between patient age and discordance in the recurrence score. For every 1-year decrease in age, the difference in recurrence scores between paired samples increased by 0.08 units (95% confidence interval − 0.14, − 0.01; p = 0.017; Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Variability in 21-gene experimental recurrence scores and 21-gene group scores between paired breast cancer samples. a Difference in 21-gene experimental recurrence scores (RS) between paired breast cancer samples by age. Recurrence scores were calculated from reference-normalised gene expression as described in the “Methods” section, and discordances were quantified by calculating the absolute difference in recurrence score between sample 1 and sample 2. Linear regressions were performed to investigate the association between the difference in recurrence score and age as a continuous variable. Data are presented as individual values. b–e Discordance in 21-gene group scores between paired breast cancer samples collected from younger women. For women aged < 50 years old, an arbitrary threshold of 4 units was set to distinguish between paired samples showing small differences in recurrence scores of ≤ 4 units (n = 9) and paired samples showing large differences in recurrence scores of > 4 units (n = 7). The 21-gene group scores were calculated for each tumour, as described in the “Methods” section, and changes in group scores between paired breast cancer samples were compared. The change in the b Proliferation group, c Oestrogen group, d HER2 group and e Invasion group scores between paired breast cancer samples. Results are presented as mean + SEM. Mean discordances were compared using the independent t test. Statistical significance was determined when p ≤ 0.05; an asterisk signifies p ≤ 0.05

The underlying gene expression changes that contribute to the increased discordance in younger women were investigated. For patients under the age of 50 years, paired breast cancer samples with minimal discordances in recurrence scores were separated from paired samples with larger discordances by setting an arbitrary threshold of 4 units. The age of 50 was selected as it is the optimal age-based proxy to distinguish premenopausal women from postmenopausal women when menopausal status is unknown [25].

Paired breast cancer samples collected from younger women with discordance > 4 units showed greater differences in the expression of Proliferation (p = 0.04; Fig. 4b) and HER2 21-gene group scores (p = 0.03; Fig. 4d), compared to paired samples with discordance ≤ 4 units. The expression of Oestrogen (p = 0.44; Fig. 4c) and Invasion (p = 0.62; Fig. 4e) group scores did not differ significantly between groups. Patient and tumour characteristics were similar between groups, and not likely to contribute to discordance (Table 2). For women over the age of 50, only one sample showed a change in recurrence score greater than 4 units which could not be statistically analysed.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients aged < 50 years with discordances in recurrence scores ≤ 4 units, compared to > 4 units

| Characteristics | ≤ 4 unit change n (%) |

> 4 unit change n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total number | 9 | 7 |

| Median age at diagnosis | 47 | 45 |

| Years; range | 41–49 | 37–47 |

| Median days between samples | 23 | 14 |

| Days; range | 10–42 | 9–29 |

| Tumour type | ||

| IDC | 8 (89) | 5 (72) |

| ILC | 1 (11) | 1 (14) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Tumour grade | ||

| 1 | 3 (33) | 2 (29) |

| 2 | 3 (33) | 2 (29) |

| 3 | 3 (33) | 2 (29) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Tumour size | ||

| ≤ 10 mm | 2 (22) | 0 (0) |

| 11–20 mm | 4 (44) | 2 (29) |

| 21–50 mm | 2 (22) | 2 (29) |

| > 50 mm | 1 (11) | 2 (29) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Lymph node status | ||

| Positive | 2 (22) | 3 (43) |

| Negative | 7 (78) | 3 (43) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||

| Present | 2 (22) | 1 (14) |

| Absent | 7 (78) | 6 (86) |

Discussion

The Oncotype DX 21-gene Recurrence Score assay is used to guide adjuvant chemotherapy treatment decisions for women with early-stage, ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. However, the Recurrence Score algorithm was largely developed and validated for use in postmenopausal women, and whether menstrual cycling in premenopausal women affects the algorithm has been a remarkably underappreciated research question. Our analysis of paired breast cancer samples provides the first evidence that patient age affects concordance in 21-gene experimental recurrence scores between paired samples of the same tumour taken on different days. Discordance is primarily due to differences in the expression of genes associated with proliferation and HER2 signalling. Consequently, Recurrence Scores generated by the Oncotype DX algorithm may be critically affected by patient age and menstrual cycle stage.

As this work was conducted on archived breast cancers, there is no clinical information surrounding the patient’s menstrual histories or menopausal status. Identification of a direct effect of menstrual cycle stage and discordance in Recurrence Score in human breast cancers would require further large-scale prospective trials. However, age-related differences in chemotherapy benefit for women with intermediate Onctoype DX Recurrence Scores have already been demonstrated [10]. Incorporation of menstrual cycle stage into future prospective studies will assist in understanding this age-related difference in chemotherapy benefit.

Increased expression of Proliferation and HER2 group genes were largely responsible for the increased variability in recurrence scores observed between paired samples. The observed variability in younger women could be a factor of menstrual cycling, as previous studies report that tumour proliferation and HER2 gene expression fluctuate during the menstrual cycle, in accordance with concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone. In premenopausal women, the highest proliferative activity of breast epithelium [28] and breast cancer samples [29] is observed during the luteal phase, when circulating concentrations of progesterone peak. Additionally, in vitro and in vivo stimulation with oestrogen and/or progesterone promotes proliferation of breast cancer cells, an effect which can be reversed with anti-estrogenic treatment [30, 31]. The expression of HER2 also fluctuates across the menstrual cycle, with the highest expression during the luteal phase [32]. Likewise, progesterone treatment of breast cancer cell lines increases growth factor receptor signalling and Oncotype DX Recurrence Scores [24]. While it has also been reported that the expression of oestrogen-regulated genes fluctuates across the menstrual cycle [20–23] and that oestrogen and progesterone affect the invasive properties of premenopausal breast cancers [33–35], we did not observe variable expression of Oestrogen or Invasion group genes between paired breast cancer samples collected from younger women.

It is interesting to note that not all young women showed discordance in recurrence scores between paired breast cancer samples. As menstrual histories of women in this study were unknown, it is possible that tissue was collected at times of the cycle when concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone did not differ significantly, or the woman was in a perimenopausal state with anovulatory cycles. As such, the impact of menstrual cycle stage on recurrence score might only be seen when there is a large enough cycle-dependent difference in circulating hormone concentrations to impact gene expression. Furthermore, biological differences between tumours may also explain why discordances in recurrence scores were only observed in a subset of tumours. There is significant heterogeneity within ER-positive breast tumours that may influence responsiveness to ovarian hormones. Paired samples exhibiting large discordances in recurrence scores may be more sensitive to fluctuations in oestrogen and progesterone and more prone to cycle-induced changes. However, the underlying tumour biology that drives this increased susceptibility, and whether it is possible to identify tumours that are more sensitive to fluctuations in oestrogen and progesterone, warrants further investigation.

There is the potential to tailor gene expression-based assays for use in premenopausal women. Incorporation of menstrual cycle stage with the Oncotype DX algorithm could provide an opportunity to improve the accuracy of the predictive benefit of chemotherapy for premenopausal women with intermediate Recurrence Scores. Alternatively, refinement of the Oncotype DX algorithm through alteration of the weighting of Proliferation and HER2 group scores could form the basis of an improved assay for premenopausal women.

Conclusions

Discordance in 21-gene experimental recurrence scores between paired breast cancer samples is inversely related to patient age and suggests that recurrence scores may be critically affected by the menstrual cycle stage at the time of tissue collection. Consequently, the use of the Oncotype DX algorithm to inform decision-making in premenopausal breast cancer patients could potentially lead to suboptimal or unnecessary treatments. Currently, there is a pressing need for consideration of patient age in the application of gene expression-based precision medicine for breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Jozef Gecz of the University of Adelaide for valuable suggestions on the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ACTB

Actin beta

- BAG1

BCL2-associated athanogene

- BCL2

B cell CLL/lymphoma 2

- BIRC5

Baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 5 (survivin)

- CCNB1

Cyclin B1

- CD68

CD68 molecule

- cDNA

Complementary DNA (cDNA)

- CSTL2

Cathepsin L2

- ER

Oestrogen receptor

- ERBB2

Erb-B2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2

- ESR1

Oestrogen receptor gene

- FFPE

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded

- GADPH

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GRB7

Growth factor receptor-bound protein 7

- GSTM1

Glutathione S-transferase mu 1

- GUSB

Glucuronidase beta

- HER2

Human epidermal growth factor receptor

- MKI67

Marker of proliferation Ki-67

- MMP11

Matrix metallopeptidase 11 (stromelysin 3)

- MYBL2

Myb proto-oncogene like 2

- PGR

Progesterone receptor gene

- RPLP0

Ribosomal protein lateral stalk subunit P0

- RS

21-gene recurrence score

- SCUBE2

Signal peptide, cub domain and Egf-like domain-containing 2

- STK15

Aurora kinase A

- TFRC

Transferrin receptor

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the study was conducted by SMB, PD, ART, TJP and WVI. Analysis and interpretation of data was conducted by SMB and WVI. The draft of the manuscript was written by SMB, with all authors providing intellectual input into the final manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Hospital Research Foundation and The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Haem/Onc Scheme A. WVI is The Hospital Research Foundation Associate Professor of Breast Cancer Research. SMB and JW are PhD candidates at the University of Adelaide and funded through Divisional and Australian Postgraduate Awards respectively. PD, SE and WVI are University of Adelaide employees. WR, DW, ART and TJP are SA Health employees.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was obtained from The Queen Elizabeth Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number Q20170106), and informed consent was obtained from study participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Low SK, Zembutsu H, Nakamura Y. Breast cancer: the translation of big genomic data to cancer precision medicine. Cancer Sci. 2018;109(3):497–506. doi: 10.1111/cas.13463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siow ZR, De Boer RH, Lindeman GJ, Mann GB. Spotlight on the utility of the Oncotype DX((R)) breast cancer assay. Int J Women's Health. 2018;10:89–100. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S124520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter SM, Rogers W, Win KT, Frazer H, Richards B, Houssami N. The ethical, legal and social implications of using artificial intelligence systems in breast cancer care. Breast. 2020;49:25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2019.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittelstadt BD, Floridi L. The ethics of big data: current and foreseeable issues in biomedical contexts. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016;22(2):303–341. doi: 10.1007/s11948-015-9652-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(27):2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, Pritchard KI, Albain KS, Hayes DF, et al. Prospective validation of a 21-gene expression assay in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2005–2014. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1510764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paik S, Tang G, Shak S, Kim C, Baker J, Kim W, et al. Gene expression and benefit of chemotherapy in women with node-negative, estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(23):3726–3734. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.7985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albain KS, Barlow WE, Shak S, Hortobagyi GN, Livingston RB, Yeh IT, et al. Prognostic and predictive value of the 21-gene recurrence score assay in postmenopausal women with node-positive, oestrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer on chemotherapy: a retrospective analysis of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70314-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparano JA, Paik S. Development of the 21-gene assay and its application in clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(5):721–728. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, Pritchard KI, Albain KS, Hayes DF, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Guided by a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(2):111–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Coates AS, Winer EP, Goldhirsch A, Gelber RD, Gnant M, Piccart-Gebhart M, et al. Tailoring therapies--improving the management of early breast cancer: St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2015. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(8):1533–1546. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris LN, Ismaila N, McShane LM, Andre F, Collyar DE, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1134–1150. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Senkus E, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rutgers E, et al. Primary breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(Suppl 5):v8–30. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NCCN. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology 2017 [V3:[Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast.pdf.

- 15.Augustovski F, Soto N, Caporale J, Gonzalez L, Gibbons L, Ciapponi A. Decision-making impact on adjuvant chemotherapy allocation in early node-negative breast cancer with a 21-gene assay: systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;152(3):611–625. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernhardt SM, Dasari P, Walsh D, Townsend AR, Price TJ, Ingman WV. Hormonal modulation of breast cancer gene expression: implications for intrinsic subtyping in premenopausal women. Front Oncol. 2016;6:241. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Ravdin PM, Makower DF, Pritchard KI, Albain KS, et al. Clinical and genomic risk to guide the use of adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(25):2395–2405. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atalay C, Kanlioz M, Altinok M. Menstrual cycle and hormone receptor status in breast cancer patients. Neoplasma. 2002;49(4):278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pujol P, Daures JP, Thezenas S, Guilleux F, Rouanet P, Grenier J. Changing estrogen and progesterone receptor patterns in breast carcinoma during the menstrual cycle and menopause. Cancer. 1998;83(4):698–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haynes BP, Viale G, Galimberti V, Rotmensz N, Gibelli B, A'Hern R, et al. Expression of key oestrogen-regulated genes differs substantially across the menstrual cycle in oestrogen receptor-positive primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138(1):157–165. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2426-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hosoda M, Yamamoto M, Nakano K, Hatanaka KC, Takakuwa E, Hatanaka Y, et al. Differential expression of progesterone receptor, FOXA1, GATA3, and p53 between pre- and postmenopausal women with estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;144(2):249–261. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2867-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haynes BP, Ginsburg O, Gao Q, Folkerd E, Afentakis M, Buus R, et al. Menstrual cycle associated changes in hormone-related gene expression in oestrogen receptor positive breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019;5:42. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0138-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes BP, Viale G, Galimberti V, Rotmensz N, Gibelli B, Smith IE, et al. Differences in expression of proliferation-associated genes and RANKL across the menstrual cycle in estrogen receptor-positive primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;148(2):327–335. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-3181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Need EF, Selth LA, Trotta AP, Leach DA, Giorgio L, O'Loughlin MA, et al. The unique transcriptional response produced by concurrent estrogen and progesterone treatment in breast cancer cells results in upregulation of growth factor pathways and switching from a luminal a to a basal-like subtype. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:791. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1819-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morabia A, Flandre P. Misclassification bias related to definition of menopausal status in case-control studies of breast cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21(2):222–228. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller BM, Brase JC, Haufe F, Weber KE, Budzies J, Petry C, et al. Comparison of the RNA-based EndoPredict multigene test between core biopsies and corresponding surgical breast cancer sections. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65(7):660–662. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Lee EH, Park HY, Kim WW, Lee RK, Chae YS, et al. Efficacy of an RNA-based multigene assay with core needle biopsy samples for risk evaluation in hormone-positive early breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):388. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5608-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navarrete MA, Maier CM, Falzoni R, Quadros LG, Lima GR, Baracat EC, et al. Assessment of the proliferative, apoptotic and cellular renovation indices of the human mammary epithelium during the follicular and luteal phases of the menstrual cycle. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7(3):R306–R313. doi: 10.1186/bcr994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Horimoto Y, Arakawa A, Tanabe M, Kuroda K, Matsuoka J, Igari F, et al. Menstrual cycle could affect Ki67 expression in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer patients. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68(10):825–829. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rochefort H, Augereau P, Briozzo P, Capony F, Cavailles V, Freiss G, et al. Structure, function, regulation and clinical significance of the 52K pro-cathepsin D secreted by breast cancer cells. Biochimie. 1988;70(7):943–949. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(88)90236-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brisken C. Progesterone signalling in breast cancer: a neglected hormone coming into the limelight. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(6):385–396. doi: 10.1038/nrc3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gompel A, Martin A, Simon P, Schoevaert D, Plu-Bureau G, Hugol D, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and c-erbB-2 expression in normal breast tissue during the menstrual cycle. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;38(2):227–235. doi: 10.1007/BF01806677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garvin S, Dabrosin C. Tamoxifen inhibits secretion of vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer in vivo. Cancer Res. 2003;63(24):8742–8748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garvin S, Nilsson UW, Huss FR, Kratz G, Dabrosin C. Estradiol increases VEGF in human breast studied by whole-tissue culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;325(2):245–251. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heer K, Kumar H, Speirs V, Greenman J, Drew PJ, Fox JN, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor in premenopausal women--indicator of the best time for breast cancer surgery? Br J Cancer. 1998;78(9):1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.