Abstract

Public health approaches to crime and injury prevention are increasingly focused on the physical places and environments where violence is concentrated. In this study, our aim is to explore the association between historic place-based racial discrimination captured in the 1937 Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) map of Philadelphia and present-day violent crime and firearm injuries. The creators of the 1937 HOLC map zoned Philadelphia based in a hierarchical system wherein first-grade and green color zones were used to indicate areas desirable for government-backed mortgage lending and economic development, a second-grade or blue zone for areas that were already developed and stable, a third-grade or yellow zone for areas with evidence of decline and influx of a “low grade population,” and fourth-grade or red zone for areas with dilapidated or informal housing and an “undesirable population” of predominately Black residents. We conducted an empirical spatial analysis of the concentration of firearm assaults and violent crimes in 2013 through 2014 relative to zoning in the 1937 HOLC map. After adjusting for socio-demographic factors at the time the map was created from the 1940 Census, firearm injury rates are highest in historically red-zoned areas of Philadelphia. The relationship between HOLC map zones and general violent crime is not supported after adjusting for historical Census data. This analysis, extends historic perspective to the relationship between emplaced structural racism and violence, and situates the socio-ecological context in which people live at the forefront of this association.

Keywords: violence, firearm injuries, discrimination, racial health disparities, redlining, historic maps, spatial analysis, Philadelphia

Introduction

There are many ways to evaluate the relationship between urban space, race and inequalities in violence. In the US, for example, firearm injury and death among black men is proportionately higher than in any other racial or ethnic group (Kalesan et al. 2014). To imagine that categories of racial and gender identities are sufficient to understand the ‘the problem (Gee & Ford 2011)’of urban violence risks vast oversimplification. From an eco-social approach (Krieger 2012), people are not just the ‘at risk’ or the ‘injured;’ they represent the embodiment of a “multilevel dynamic and co-constituted social and ecological context,” which shapes “health, disease, and well-being within and across historical generations.” (Krieger 2016) In this perspective, if we limited the cause and consequence of urban violence to black men, we may easily conflate the complex processes that concentrate violence within specific urban places with the people who live there (Greenberg & Schneider 1994). In fact, sociologists from the Chicago School have demonstrated that certain city neighborhoods have maintained high rates of crime and violence over decades despite substantial change in the racial and ethnic makeup of the population in those areas (Shaw & McKay, 1942).

Emerging approaches to the reduction of violent crime and violent injuries are increasingly place-based, with focus on the urban environments where violence is endemic. Public health programs like urban greening and building remediation, for example, have been shown to effectively reduce violent crime and improve safety across large and diverse urban populations (Link & Phelan, 1995;Branas, Cheney, MacDonald, Tam,…Ten Have 2011; Branas & Macdonald 2014; Kondo, Keen, Hohl, MacDonald & Branas 2015). Sociologists who study urban violence through a social disorganization perspective similarly emphasize the importance of place in creating the context of crime (Sampson, 2012). And recent criminal justice strategies now consider urban places like block-level violence “hot spots” as an ideal target for law enforcement-based violence prevention (Braga et al. 2010; Koper, Sergeant & Lum 2015).

In this study, our aim is to add a historical dimension to the association between violence and city spaces. In their seminal studies of Chicago, Sampson and colleagues demonstrate how neighborhood crime and disorder are a legacy of the city’s social and economic inequality (Sampson, 2012; Sampson & Morenoff, 2006; Sampson & Sharkey, 2008). Our purpose, here, is to explore how the distribution of urban violence is associated with historical forms of structural racism. We define structural racism as the institutions, ideologies, and processes that operate at a socio-ecological level and which are able to adapt to changing sociopolitical contexts and persist over time (Gee & Ford 2011). We use as an exemplar, the city of Philadelphia, which has been both a mainstay of urban life in the United States (US) and the very setting in which Du Bois first described connections between racism, social inequality, and health (Du Bois 1996).

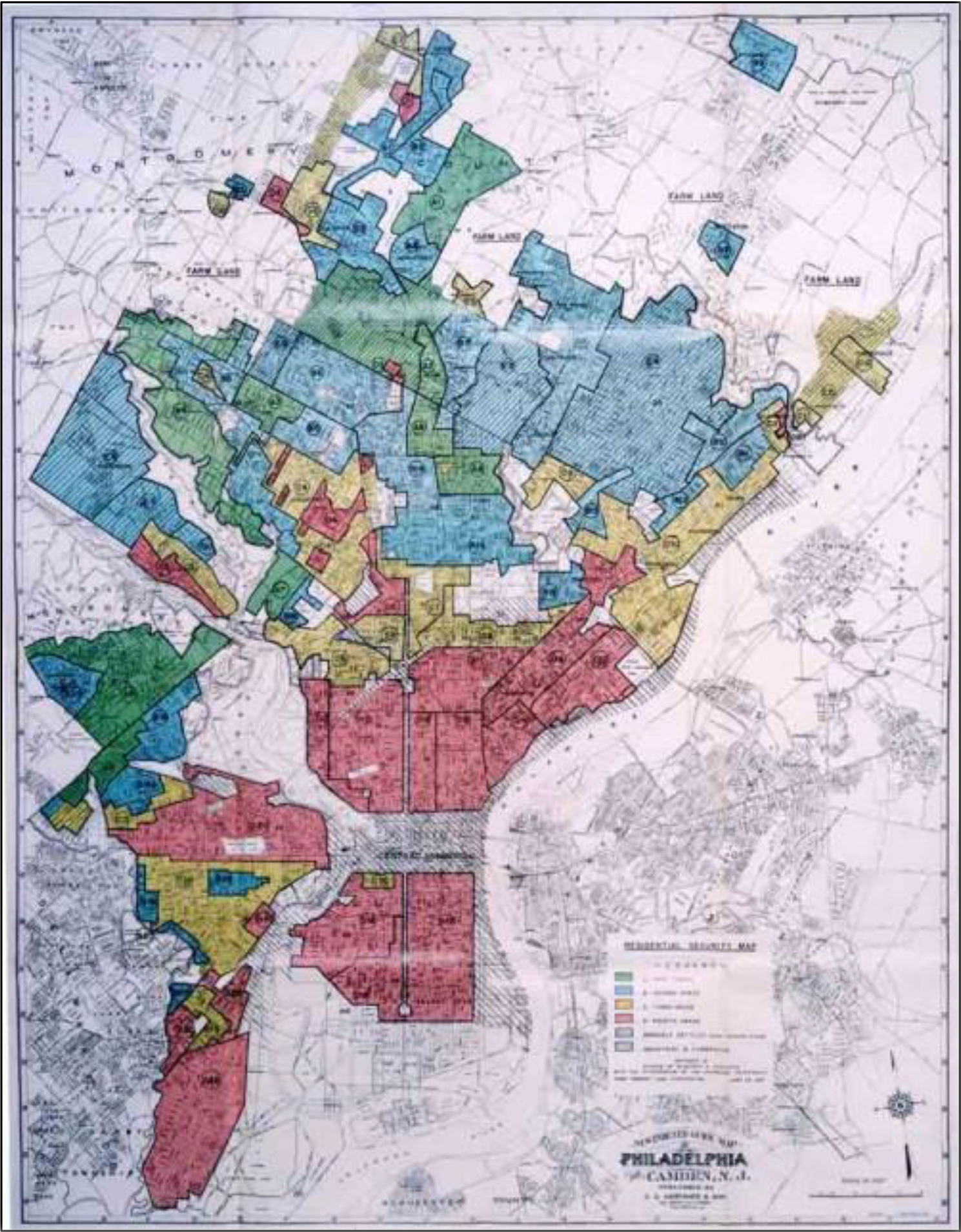

As secondary goal we explore how maps can be used to historicize spatial relationships between violence concentrations and urban space (Pulido 2000). In this study, we use the 1937 Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) map of Philadelphia that was created in the service of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board (FHLBB) (Figure 1). The HOLC was commissioned by the Franklin Roosevelt Administration as part of New Deal in effort to stem the tide of housing foreclosures in wake of the Great Depression (Guttentag & Wachter 1980). The HOLC together with the Federal Housing Association of 1937 became major actors who determined which urban areas were attractive for bank and financial service company investment and which were not (Guttentag & Wachter 1980). In 1935 the HOLC began a city survey program to create residential security maps in 239 cities. These maps were used to indicate the relative likelihood that real estate investments would appreciate over time from the point of view their creators, who were often ‘consultants’ with local financial interests such as lenders, realtors and appraisers (Hillier 2003).

Figure 1.

1937 Home Owners’ Lending Corporation zoning map*

HOLC map-makers in the 1930s assimilated racial and ethnic composition into their assessment of the worthiness of specific urban spaces for government-backed investment and economic development (Hillier 2003; Crossney & Bartelt 2005; Hillier 2005). The FHLBB Division of Research and statistics asked that map-creators grade neighborhoods in a quaternary system. A first-grade or green color zone represented areas assessed to be ideal for investment vis-a-vis affluent home buyers and plentiful space for development. A second-grade or blue zone was assigned to areas deemed well-developed and stable. A third-grade or yellow zone represented areas with evidence of decline and influx of a what was termed a “low grade population,” with a fourth-grade or red zone reserved for areas with dilapidated or informal housing stock and an “undesirable population” of Blacks, immigrants and Jews (Hiller 2005).

The mapping practices that informed the development of HOLC maps (known more commonly as “redlining” for the red-zones on maps), was an explicit form of place-based discrimination (Hillier 2003) intended to shelter government financial investment in the ‘desirability’ of white and higher income geographies. As Wilder describes (2000) in his study of the progressive decline of Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, the HOLC not only shifted financial resources across the city (in this case from North to South Brooklyn), it “drew a line of racial separation across the heart of the borough. (pp. 194).” In effort to sustain the availability of federal resources for neighborhood investments and housing value, white residents of mixed Brooklyn neighborhoods sought homogenous communities where financially “dangerous” Black neighbors were not welcome or pushed out.

In the case of Philadelphia, there is not sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the 1937 HOLC map was extensively used by local mortgage originators leading directly to divestment in minority communities (Hillier 2003; Hillier 2005). The map is, nonetheless, a historic illustration of the racialized hierarchicalization of urban space (Aalbers 2014) in New Deal era Philadelphia. The map’s makers with a “rhetorical role in defining the configurations of power in society,” recorded their interpretation of the racist social forces and ideologies of their time as “manifestations in the visible landscape. (Harley 1988)”

Methods

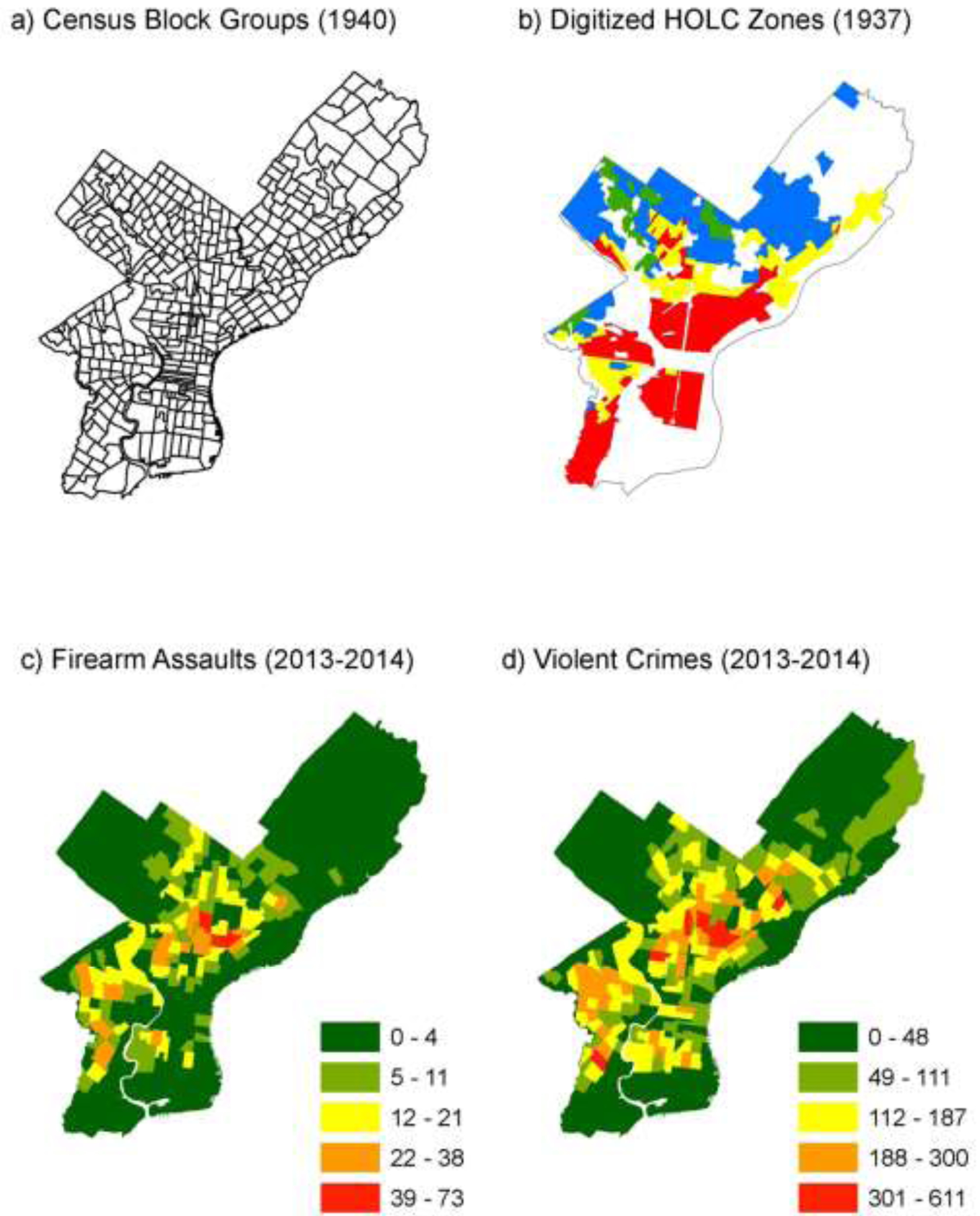

The HOLC map is a spatial representation of place-based racial discrimination in 1930s Philadelphia. We therefore designed an empirical spatial analysis to test the relationship between historically racialized assignments of urban space and the present-day distribution of the city’s violence. Our units of analysis were 1940 Census tracts that have internal centroids located within the present day city limits of Philadelphia (n = 404; Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Geographic characteristics, Philadelphia

1937 HOLC Zones

The main independent variables are the color-coded zones depicted in the 1937 HOLC map (Figure 1). Following the work of Hillier (Hillier, 2003), we imported the map image as a raster layer into ArcMap v.10.3.1 (ESRI 2014), then aligned this layer with Census 2010 blocks. Blocks were assigned to one of five categories (green, blue, yellow, red, or not zoned) in which their center point (internal centroid) was located. Most blocks were wholly contained within a single HOLC zone category, but due to some changes in street layouts over 80 years (e.g. new freeways), there was some minor misalignments between block boundaries and HOLC zone boundaries. Having digitally approximated the boundaries of HOLC zones (Figure 2b), we then assigned Census 2010 blocks to Census 1940 tracts based on the location of their internal centroid. We calculated the proportion of land area in each 1940 Census Tract that comprised each of these designations.

1940 Census Demographics

HOLC assessments were based, at least in part, on the demographic composition of neighborhoods. To account for the possibility that relationships we see between 1937 HOLC zones and present day violence is confounded by the demographic distribution of the city’s population near the time of map creation, we calculated measures of population demographics from the 1940 decennial Census. These data are available from the National Historical Geographic System (Minnesota Population Center, 2016). In theory, demographic data from before 1937 would be preferable for this analysis, because of the possibility that the HOLC maps shaped the urban social landscape, and that 1940 demographic characteristics in fact mediate relationships between HOLC zones and present day violence (Petersen, 2006; Imai, Keele, Tingley, 2010). However, the 1940 Census provided more expansive demographic characteristics than the 1930 Census, and we considered it highly unlikely that the map, even if widely distributed, would have drastically altered the geographic distribution of the city residents over the course of three years.

To be considered a potential confounder of the relationship between 1937 HOLC zones and present day violence, 1940 Census variables must (i) relate to HOLC designations, (ii) affect subsequent land use in ways that could shape geographic distributions of violence (for example, areas that are persistently disadvantaged over decades), and (iii) not lie on the causal path between HOLC zones and violence (Rothman, Greenland, Lash, 2008). Three measures available in the 1940 Census met these criteria: (1) the proportion of the population who were Black, (2) the median value of owner occupied homes (in 1940 $US), and (3) an index of historic ‘concentrated disadvantage,’ described below.

Concentrated Disadvantage

Concentrated disadvantage represents compounded place-based economic disinvestment, social disorganization and political marginalization (Sampson, 2012). Previous research suggests internally consistent indices can be calculated using routinely collected Census variables. These include: the proportion receiving public assistance, the proportion of female-headed households, racial composition (percentage black) and density of children (Sampson et al. 1997). Indices can be calculated using factor analysis or by taking a sum of the variables (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Andreias et al., 2010) to capture the construct of concentrated disadvantage in a single metric.

In the case of the 1940 Census, very few variables used in conventional measures of concentrated disadvantage were available. However, we considered that some 1940 variables would provide adequate proxies. For our concentrated disadvantage index we calculated the sum of: the proportion of the population aged ≥ 25 years without a high school certificate, the proportion of homes that were renter occupied, the proportion of homes without a radio, the proportion of homes without a mechanical refrigerator, the proportion of homes without central heating, and the proportion of homes with more than one person per room. Measured in terms of Spearman correlation coefficients (Table 1), these variables were mostly moderately (0.4 ≤ ρ < 0.7) or highly correlated (ρ ≥ 0.7); the internal consistency was also high (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.810). We considered other variables for inclusion in the index (e.g. proportion of men aged ≥ 14 years who were unemployed), but these measures were poorly correlated with other measures (ρ < 0.4) and likely had different social meaning in 1940 when compared to the present day. Median home value was moderately correlated with the index of concentrated disadvantage (ρ = −0.443).

Table 1.

Spearman correlation coefficients; 1940 Census tracts Philadelphia (n = 404)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age ≥ 25 years without a High School certificate (%) | 1.000 | |||||

| 2. Tenant occupied dwellings (%) | 0.245 | 1.000 | ||||

| 3. Dwellings without a radio (%) | 0.461 | 0.458 | 1.000 | |||

| 4. Dwellings without a mechanical refrigerator (%) | 0.676 | 0.566 | 0.719 | 1.000 | ||

| 5. Dwellings without central heating (%) | 0.412 | 0.278 | 0.689 | 0.644 | 1.000 | |

| 6. Dwellings with ≥ 1 person per room (%) | 0.648 | 0.460 | 0.667 | 0.825 | 0.612 | 1.000 |

Present-day Violence

Our dependent measures were counts of (i) firearm assaults and (ii) violent crimes that occurred in Philadelphia in 2013–2014 and were recorded by the Philadelphia Police Department (PPD). The PPD routinely collects and maintains these data. We defined firearm assaults as any event in which a person was intentionally injured by a firearm by another person or groups of people, and violent crimes as any homicide, rape, robbery or aggravated assault. Each event is documented by the street address on which it occurred (masked to the city block; e.g. 1000 block of Market St). We geocoded the point locations of all firearm assaults and violent crimes and then calculated counts of these events within the 1940 Census tracts (Figures 2c and 2d).

Statistical Analysis

We constructed Poisson models for counts of firearm assaults (Model 1) and violent crimes (Model 2) within the 1940 Census tracts. We created three different versions of each model. First, we included only the 1937 HOLC categorizations of red, yellow, blue and no zone, reserving green as a reference category. Second, we included only the 1940 Census measures of proportion Black, median home income, and concentrated disadvantage (standardized). Very few residents were recorded as races other than Black or White in 1940 (Table 2), so we reserved the proportion White and other race as a reference category. Third, we included all independent measures (i.e. the HOLC zones and the 1940 Census measures) in a single model. We expected there to be more present day violence in Census tracts with larger present day populations, so all models used present day population as an expectancy variable (similar to an off-set in negative binomial regression). We estimated population size by taking the sum of the populations for all blocks with an internal centroid inside the boundary of each 1940 tract (using American Community Survey 5 year estimates of population size for 2014).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics; 1940 Census tracts, Philadelphia (n = 404)

| Mean | SD | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present Day Characteristics | ||||

| Shootings (2013–2014) | 5.317 | 8.678 | 0 | 73 |

| Violent crimes (2013–2014) | 80.517 | 85.849 | 0 | 611 |

| Population (ACS 5-year estimate 2014) | 3777.238 | 2981.639 | 2 | 16013 |

| HOLC Zone (% of land area) | ||||

| Red | 27.817 | 39.396 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Yellow | 15.127 | 28.864 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Blue | 23.745 | 37.546 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Green (reference) | 4.745 | 17.403 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| No zone | 28.565 | 38.150 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| 1940 Census Variables | ||||

| White and other race (%) | 90.023 | 19.020 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Black (%) | 9.878 | 18.994 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Median house value (1940 $US) | 2686 | 2590 | 0 | 16278 |

| Age ≥ 25 years without a high school certificate (%) | 77.835 | 16.685 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Tenant occupied dwellings (%) | 57.469 | 19.758 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Dwellings without a radio (%) | 5.629 | 11.166 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Dwellings without a mechanical refrigerator (%) | 38.515 | 26.809 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Dwellings without central heating (%) | 12.887 | 20.380 | 0.000 | 100.000 |

| Dwellings with ≥ 1 person per room (%) | 10.908 | 8.692 | 0.000 | 62.500 |

Conventional statistical methods assume that units of analysis are independent of one another, however when data are aggregated within spatial units, nearby units tend to be more alike than distant units (Tobler 1970). To account for this possibility, our Poisson models included a conditional autoregressive random effect, and we used a Bayesian procedure to fit the models to the data (Waller & Gotway 2004). This approach produces a median estimate and a 95% credible interval. Where the credible intervals around the median estimate do not include a value of 1.00, the relationships can be considered well-supported (which is analogous to achieving statistical significance in standard regression analyses) (Lunn, Thomas, Best, & Spiegelhalter 2000).

We conducted several sensitivity analyses to ensure that our results were not due to model specification. First, we tested alternate constructions of the measure of concentrated disadvantage, systematically omitting the component variables and including other candidate measures (e.g. male unemployment rate). Second, we added the natural logarithm of each Census tract’s land area as an independent variable, to account for the possibility that red zoned areas were more densely populated. Third, we recomposed the analyses using 2010 Census tracts as the units of analysis, and replaced the 1940 Census measures with corresponding measures from 2014 (i.e. American Community Survey 5-year estimates of proportion Black, median household income, and concentrated disadvantage). Although we recognized that 2014 characteristics more likely mediated than confounded the relationships between 1937 HOLC zones and present day violent crime, we considered it was important to assess whether altering the year of the demographic measures materially affected the main associations of interest.

Results

In total, there were 2,148 firearm assaults and 32,529 violent crimes in Philadelphia between 2013 and 2014. Of the 135.9 square miles that covered the 404 included 1940 Census tracts, 4.1% of land was categorized as grade-A or a green zone, 21.1% was categorized blue, 12.4% was categorized yellow, 19.8% was categorized red, and 42.6% was not graded or included in the 1937 HOLC evaluation. Census tract characteristics are presented in Table 2.

Model 1 evaluates firearm violence in relationship to the 1937 HOLC map categorizations. In Model 1a, firearm violence is around 13 times higher in tracts that were exclusively categorized within a red zone in 1937 compared to tracts exclusively categorized as within a green zone (IRR =13.1, 95% CI: 3.8, 47.4). Tracts categorized as yellow had more than 8-fold greater incidence (IRR = 8.8, 95% CI: 2.6, 30.5) of firearm violence, and tracts categorized as blue had 4-fold greater incidence (IRR = 4.2, 95% CI: 1.4, 14.1). After adjusting for 1940 Census measures these effects were attenuated (Model 1c), but parameter estimates remained strongly supported and progressive, or what might be considered, dose-responsive. Census tracts within historical red zones were associated with an 8-fold greater incidence of firearm violence (IRR = 8.7, 95% CI: 2.2, 36.3), yellow zones were associated with a 7-fold increase (IRR = 7.0, 95% CI: 1.9, 28.8), and blue zones were associated with a 4-fold increase (IRR = 3.9, 95% CI: 1.2, 14.2). Results of the sensitivity analyses were substantively similar to the results of the main effects models here and for all subsequent analyses.

Model 2 assesses the relationships for all types of violent crimes and the 1937 HOLC map categorizations. In unadjusted analyses, when compared to green zones, red zones (IRR = 5.5, 95% CI: 2.5, 14.3), yellow zones (IRR = 4.2, 95% CI: 1.7, 10.4), and blue zones (IRR = 2.7, 95% CI: 1.2, 6.5) were associated with higher incidence of violent crimes. In Model 2c, after adjusting for 1940 Census measures these relationships were no longer supported. However, tracts that were not zoned in 1937 had 4.5 times more violent crimes than green-zoned tracts (IRR = 4.5, 95% CI: 1.6, 17.3) and tracts with more concentrated disadvantage in 1940 are associated with more violent crimes (IRR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.1, 1.7).

Discussion

When we look at the 1937 HOLC Map in relationship to contemporary violence and firearm assaults, we find that the same places that were imagined to be areas unworthy of economic investment by virtue of the races, ethnicities, and religions of their residents are more likely to be the places where violence and violent injury are most common almost a century later. Even after adjusting for the socio-demographic factors that contributed to unfavorable historical assessment of these geographic areas, firearm injuries, which are arguably the most dangerous, threatening and infectious consequences of violence (Rowhani-Rahbar et al. 2015) appear to occur most frequently in with historically red-zoned areas of the 1937 HOLC map. The association between the HOLC map zone and overall violent crimes is also noteworthy: in comparison to green or first-grade zones all other mapped zones have significantly and a nearly progressive increased likelihood of present day violent crime incidence; this association, however, was explained by demographic characteristics at the time the maps were produced.

This single ecological analysis does not prove the insidious confluence of historical structural racism and racialized concentration of violence exposure in urban space. It does, however, add historical dimension to previous studies of urban violence that have demonstrated how racial disparities in violent injury victimization and perpetration are as much an issue of place as they are of people (Branas, Jacoby, Andreyeva 2017). The HOLC maps of the 1930s reflect historical perceptions of the quality of built environment, residents’ races and ethnicities, and relative economic power. These same factors remain among the most important predictors of violence and violent injuries in today’s urban landscapes (Krivo et al. 2009, Branas et al. 2011, Culyba et al. 2016). Blacks and Latinos are most likely to reside in disadvantaged urban communities and live their lives with exposure to, if not direct experience of, the physical, social and psychological consequences of violent crime and violent injuries (Krivo et al. 2009). We recently demonstrated that black residents of Philadelphia have approximately 5-fold increased risk of being assaulted with a firearm compared to white residents, and that excess risk is independent of the median household income of the Census tract in which people live (Beard et al., 2017).

The relationship between dangerous urban space and specific categories of city residents can be understood as a product of intergenerational social and economic exclusion. These exclusions, once purposeful and overt, have become less visible and indeed, illegal, under policies like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968. A prevailing theory maintains that while difficult to see without a historic perspective, place-based discrimination is enacted through racialized stigma whereby for, “neighborhoods and people labeled as hazardous, deleterious influences remain an inescapable generational dilemma (Woods, Shaw-Ridley & Woods 2014).” The perception or designation of areas as disreputable or disordered, may set in motion long-term processes that reinforce stigmatized areas and contribute to the legacies of inequality (Sampson 2012). Representations of urban space like the HOLC Maps have social meaning and create cascading feedback loops by encouraging people to move out of degraded areas whenever possible, leading to further stigmatization and future increases in concentrated disadvantage. Sampson (2012) contended that “collective (or intersubjectively shared) perceptions form a context that constrains individual perceptions and social behavior” (p.131). This logic partially explains why the disinvested neighborhoods are now heavily policed. Skogan (1990), found that high rates of crime and violence were associated with higher rates of neighborhood dissatisfaction, fear and intentions to move out. Sampson and colleagues (Morenoff & Sampson 1997; Sampson 1986) also observed that increases in homicide and robbery rates was associated with (white) population decline and increase in racially segregated poverty. When those with the means of residential mobility moved out, not surprisingly, crime and violence “hot spots” emerged and then became the target of intensive policing. Massey (1990) argues that segregation, forged through the housing market, is a key element to the concentration of urban poverty and the intensification of social and economic deprivation among Black city residents. In 2010, Philadelphia was one of 21 US cities with the highest Black populations to live within extreme relative segregation in the context of the city (Massey 2015). The isolation of black city residents can have profound negative consequences for individuals and communities by creating barriers to the services of mainstream institutions and access to the formal labor market (Shihadeh and Flynn, 1996). Segregation also has well-established associations with health conditions including violent injuries and deaths (Williams & Collins 2011; Crowder & Krysan 2016; Sampson & Winter 2016). Sampson, Morenoff and Raudenbush (2005) tested a suite of hypotheses on the etiologies of racial disparities in violence in the city of Chicago. Self-reported violence perpetration was 85% higher in Black respondents and 10% lower in Latino respondents, when compared to White respondents. After contextualizing these data with individual, family, and neighborhood factors, racial and ethnic differences were almost entirely explained by family structure, immigration history and neighborhood social context. Racial segregation in unequal neighborhood environments, therefore, may be understood as an essential and modifiable condition that explains racial differences in violence perpetration and victimization. Segregation in Philadelphia may have not been caused by a map, but the processes through which racialized steering in housing availability developed across the urban landscape is embedded well within it.

The 1937 HOLC map is a snapshot of a phenomenon that is both ecologic and sociologic. Hall writes that “to envisage the city as (a backdrop to life), is to misapprehend the way in which lived experience always unfolds in reciprocal engagement with…the urban landscape (Hall 2008).” The use of a historic map provides a long-view into the eco-social reciprocity we see in today’s Philadelphia. This is important lest we imagine that there are ahistorical, unmediated and natural differences between the people who live in urban ecologies that flourish and foster healthy conditions, and others, just a few miles, blocks, or houses away, who live in places considered dangerous and pathologic. And though untraditional in its approach to violence epidemiology, this kind of exploration is supported by work done by other to evaluate racialized urban eco-social relationships using maps. More than half a century ago, in the classic sociologic study urban racial dynamic in Chicago, Black Metropolis depicted a synergistic connection among seemingly disparate dimensions sof place-based disadvantage (Drake & Cayton 1945). More recently, oral histories, maps and news media that remarked on social controls within Philadelphia’s mid-20th century public park system, have been used to illustrate the historical roots of fear of parks which has led to exclusion, particularly among Black women, from the benefit of these spaces (Brownlow 2006).

This study, while novel, must be interpreted within the context of its limitations. It is well established that firearm violence and violent crime occur more frequently in places where the proportion of racial and ethnic minority residents are highest and social disadvantages like poverty and lower average educational attainment are spatially concentrated (Sampson & Wilson 1995; Messner, Baum & Rosenfeld 2004; Sampson & Morenoff 2005; Beard et al. 2017). Some neighborhoods of Philadelphia may have been changed significantly since the 1930s. However, place-based population changes in Philadelphia are not as rapid as in many other cities with developing economies; gentrification in the Philadelphia is associated with a relatively slow pace of resident displacement due to high vacancy rates, and less advantaged residents, when displaced, typically move to similar less advantaged neighborhoods (Ding, Hwang, & Divringi 2016). It is also possible that Philadelphia’s neighborhood conditions are what might be considered, ‘temporally autocorrelated’ within many areas of the city (places with lower income continue to have lower income over time), even from 1937 and 2014. In that context, the current study is limited to simple assessment of correlations between HOLC zones and present day violence and crime. We were able to adjust for some basic demographic characteristics assessed around the time the map was created (e.g. concentrated disadvantage), and found that these explained the relationships between HOLC zones and present day violent crime but not firearm assaults. One possible explanation is that places that were disadvantaged eighty years ago may also be disadvantaged now, and violence is a symptom (and perhaps also a cause) of this entrenched deprivation.

The 1937 HOLC map reflected some of the many factors that shaped the development of redlining and racial segregation in Philadelphia (Hillier 2003: Hillier 2005). A thorough investigation of the dynamic inter-relationships over time that lead to such findings (e.g. between the racial and ethnic composition of resident populations, HOLC zones, mortgage lending practices, neighborhood socio-economic conditions, and crime and violence) are well beyond the scope of this paper; however our results suggest this will be an important area for further research. Such studies should consider the possibility that present day demographic characteristics mediate and/or moderate relationships between HOLC zones and present day crime and violence (Petersen et al. 2006; Imai et al. 2010). Recent studies of contemporary racial bias in mortgage lending have been linked to disparities in conditions like breast cancer, and it is likely that actual mortgage lending data will yield the best estimates of the causative relationship between contemporary urban disinvestment and place-based disadvantages (Beyer et al. 2016). The 1937 map also did not categorize all areas of the city of Philadelphia and when compared to its present demography, information on several now-populated city spaces were not developed or residential in the 1930s. Finally, in our analyses we controlled for factors that are not in and of themselves empiric realities but rather are defined by the context of their historical moment. We recognize that categories of race, ethnicity and definitions of poverty, concentrated disadvantage are social constructions that could never really ‘adjust’ for the complex eco-social milieu in which violent interactions take place. Nonetheless, we believe that this unconventional application of spatial analysis brings to light the way in which the representation of racially discriminatory thought illustrated within a historical map reflects back the violence and racialized social problems of Philadelphia today.

Conclusion

There is opportunity to critically evaluate the history inherent in maps and other representations of structural racism to conceptualize public health approaches to violent places that integrate the life course of the city itself. This kind of approach to injury prevention would extend the temporal frame through which we understand the associations between exposures and outcomes across generations and keep the ecological context in which people live at the forefront. Place-based innovations in public health and violence prevention may benefit from consideration of historic context, and focused attention on the urban spaces that retain, most deeply, the scars of a racist past.

Table 3.

Bayesian conditional autoregressive Poisson models for counts of firearm assaults; 1940 Census tracts, Philadelphia (n = 404)

| Model 1a | Model 1b | Model 1c | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | (95% | CI) | IRR | (95% | CI) | IRR | (95% | CI) | |||

| HOLC Zone | |||||||||||

| Green (reference) | |||||||||||

| Blue (100% increase) | 4.212 | 1.386 | 14.055 | 3.904 | 1.179 | 14.239 | |||||

| Yellow (100% increase) | 8.820 | 2.614 | 30.569 | 7.092 | 1.908 | 28.760 | |||||

| Red (100% increase) | 13.144 | 3.773 | 47.371 | 8.732 | 2.241 | 36.343 | |||||

| No Zone (100% increase) | 10.990 | 3.267 | 38.513 | 7.323 | 1.870 | 30.114 | |||||

| 1940 Census Variables | |||||||||||

| Black (10% increase) | 1.016 | 0.924 | 1.118 | 1.016 | 0.924 | 1.117 | |||||

| House value ($1,000 increase) | 0.918 | 0.841 | 0.997 | 0.946 | 0.865 | 1.036 | |||||

| Concentrated Disadvantage (z-score) | 1.387 | 1.018 | 1.884 | 1.253 | 0.913 | 1.730 | |||||

| Proportion variance explained by spatial random effect | 1.000 | 0.986 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.985 | 1.000 | 0.999 | 0.980 | 1.000 | ||

Nb. Bolding denotes credible intervals do not include the null value of 1.000, providing evidence of an association

Table 4.

Bayesian conditional autoregressive Poisson models for counts of violent crimes 2013–2014; 1940 Census tracts, Philadelphia (n = 404)

| Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 2c | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | (95% | CI) | IRR | (95% | CI) | IRR | (95% | CI) | |||

| HOLC Zone | |||||||||||

| Green (reference) | |||||||||||

| Blue (100% increase) | 2.711 | 1.282 | 6.534 | 1.863 | 0.718 | 6.639 | |||||

| Yellow (100% increase) | 4.225 | 1.683 | 10.392 | 2.415 | 0.800 | 8.882 | |||||

| Red (100% increase) | 5.518 | 2.466 | 14.325 | 2.571 | 0.913 | 11.001 | |||||

| No Zone (100% increase) | 10.665 | 4.568 | 26.128 | 4.531 | 1.565 | 17.288 | |||||

| 1940 Census Variables | |||||||||||

| White and Other Race (reference) | |||||||||||

| Black (10% increase) | 0.981 | 0.902 | 1.069 | 0.995 | 0.916 | 1.079 | |||||

| House value ($1,000 increase) | 0.906 | 0.852 | 0.955 | 0.946 | 0.888 | 1.001 | |||||

| Concentrated Disadvantage (z-score) | 1.451 | 1.199 | 1.774 | 1.354 | 1.124 | 1.656 | |||||

| Proportion variance explained by spatial random effect | 0.925 | 0.766 | 0.999 | 0.960 | 0.859 | 0.998 | 0.959 | 0.842 | 0.997 | ||

Nb. Bolding denotes credible intervals do not include the null value of 1.000, providing evidence of an association

References

- AALBERS MB, 2014. Do maps make geography? Part 1: Redlining, planned shrinkage, and the places of decline. ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies, vol. 13, pp. 525–556. [Google Scholar]

- ANDREIAS L, BORAWSKI E, SCHLUCHTER M, TAYLOR HG, KLEIN N, HACK M, 2010. Neighborhood influences on the academic achievement of extremely low birth weight children. J. Pediatr. Psychol. vol 35, pp. 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEARD J, MORRISON CM, JACOBY SF, DONG B, SMITH R, SIMS C, WEIBE D, 2017. Quantifying disparities in urban firearm violence by race and place in Philadelphia, PA: A Cartographic Study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BEYER KM, ZHOU Y, MATTHEWS K, BEMANIAN A, LAUD PW and NATTINGER AB, 2016. New spatially continuous indices of redlining and racial bias in mortgage lending: links to survival after breast cancer diagnosis and implications for health disparities research. Health & Place, 20160509, May 9, vol. 40, pp. 34–43 DOI S1353-8292(16)30047-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAGA AA, PAPACHRISTOS AV and HUREAU DM, 2010. The Concentration and Stability of Gun Violence at Micro Places in Boston, 1980–2008. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 33. [Google Scholar]

- BRANAS CC, CHENEY RA, MACDONALD JM, TAM VW, JACKSON TD, and TEN HAVE TR, 2011. A difference-in-differences analysis of health, safety, and greening vacant urban space. Am J Epidemiol, vol. 194, no.11, pp. 1296–1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRANAS CC and MACDONALD JM, 2014. A simple strategy to transform health, all over the place. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice: JPHMP, Mar-Apr, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 157–159 ISSN 1550–5022; 1078–4659. DOI 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000051 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRANAS C, JACOBY SF, ANDREYEVA E, 2017. Firearm violence as a disease- “hot people” or “hot spots”? JAMA Internal Medicine, DOI: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.8273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWNLOW A, 2006. An archaeology of fear and environmental change in Philadelphia. Geoforum, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 227–245. [Google Scholar]

- CROSNEY & BARTLET, 2005 Crossney KB and Bartelt DW, 2005. The legacy of the home owners’ loan corporation. Housing Policy Debate, 16(3–4), pp.547–574. [Google Scholar]

- CROWDER K and KRYSAN M, 2016. Moving Beyond the Big Three: A Call for New Approaches to Studying Racial Residential Segregation. City and Community, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 18–22. DOI 10.1111/cico.12148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CULYBA AJ, JACOBY SF, RICHMOND TS, FEIN JA, HOHL BC, and BRANAS CC, 2016. Modifiable neighborhood features associated with adolescent homicide. JAMA Pediatr vol. 170, no. 5, pp. 473–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DING L, HWANG J, DIVRINGI E, 2016. Gentrification and residential mobility in Philadelphia, Regional Science and Urban Economics, vol. 61, pp. 38–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRAKE SC, 1945. Black metropolis; a study of Negro life in a northern city. New York, Harcourt, Brace and Co. [Google Scholar]

- DU BOIS WEB, 1996. The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI, 2014. ArcGIS Desktop: Release 10.3 Redlands, CA: Environmental Systems Research Institute. [Google Scholar]

- GEE GC and FORD CL, 2011. Structural Racism and Health Inequities: Old Issues, New Directions. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, vol. 8, pp. 115–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREENBERG M and SCHNEIDER D, 1994. Violence in American cities: young black males is the answer, but what was the question?. Social Science & Medicine, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUTTENTAG GM and WACHTER SM, 1980. Redling and Public Policy. New York: New York University. [Google Scholar]

- HALL T, 2008. Hurt and the city: Landscapes of urban violence. Social Anthropology, vol.16, pp. 63–76. [Google Scholar]

- HARLEY JB, 1988. Maps, knowledge, and power from Cosgrove D and Daniels S, eds. The Iconography of Landscape. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 277–312. [Google Scholar]

- HILLIER AE, 2003. Redlining and the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation. Journal of Urban History, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 394. [Google Scholar]

- HILLIER AE, 2005. Residential Security Maps and Neighborhood Appraisals. Social Science History. vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 207–233. [Google Scholar]

- KALESAN B, VASAN S, MOBILY ME, VILLARREAL MD, HLAVACEK P, TEPERMAN S, FAGAN JA and GALEA S, 2014. State-specific, racial and ethnic heterogeneity in trends of firearm-related fatality rates in the USA from 2000 to 2010. BMJ open, vol. 4, no. 9, pp. e005628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONDO MC, KEENE D, HOHL BC, MACDONALD JM, and BRANAS CC, 2015. A difference-in-differences study of the effects of a new abandoned building remediation strategy on safety. PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOPER CS, SERGEANT JE, and LUM C, 2015. Institutionalizing place-based approaches: Opening ‘cases’ on gun crime hot spots. Policing, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 243–254. doi: 10.1093/police/pav023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- KRIEGER N, 2016. Living and Dying at the Crossroads: Racism, Embodiment, and Why Theory Is Essential for a Public Health of Consequence. American Journal of Public Health, vol. 106, no. 5, pp. 832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRIEGER N, 2012. Methods for the Scientific Study of Discrimination and Health: An Ecosocial Approach. American Journal of Public Health, vol. 102, no. 5, pp. 936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRIVO LJ, PETERSON RD and KUHL DC, 2009. Segregation, racial structure, and neighborhood violent crime. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 114, no. 6, pp. 1765–1802. DOI 10.1086/597285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMAI K,., TINGLEY D, 2010. A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological methods. Vol 15, pp. 309–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVENTHAL T, BROOKS-GUNN J, 2000. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol. Bull 126,309–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASSEY DS, 1990. American Aparteid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. American Journal of Sociology, vol. 96, pp. 329–357. [Google Scholar]

- MASSEY DS, 2015. The Legacy of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Sociological Forum, vol. 30, no. S1, pp. 571–588. DOI 10.1111/socf.12178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MESSNER S, BAUMER E, and ROSENFELD R, 2004. Dimensions of social capital and rates of criminal homicide. American Sociological Review, vol. 69, pp. 882–903. [Google Scholar]

- MINNESOTA POPULATION CENTER, 2016. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 11.0 Minneapolis: University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- MORENOFF J and SAMPSON R, 1997. Violent crime and the spatial dynamics of neighborhood transition: Chicago, 1970–1990. Social Forces, vol. 76, pp. 31–64. [Google Scholar]

- LUNN DJ, THOMAS A, BEST N and SPIEGELHALTER D, 2000. WinBUGS - A Bayesian modelling framework: Concepts, structure, and extensibility. Statistics and Computing, vol. 10, pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar]

- PETERSEN ML, SINISI SE, VAN DER LAAN MJ, 2006. Estimation of direct causal effects. Epidemiology, vol. 17, pp. 276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PULIDO L, 2000. Rethinking environmental racism: White privilege and urban development in Southern California. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 90, no. 1, pp. 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- ROTHMAN K, GREENLAND S, and LASH TL, 2008. Modern Epidemiology, 3rd Edition Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- ROWHANI-RAHBAR A, ZATZICK D, WANG J, MILLS BM, SIMONETTI JA, FAN MD and RIVARA FP, 2015. Firearm-related hospitalization and risk for subsequent violent injury, death, or crime perpetration: A cohort study violent injury, death, or crime perpetration after firearm-related hospitalization. Annals of Internal Medicine, vol. 162, no. 7, pp. 492–500 DOI 10.7326/M14-2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPSON RJ 1986. The contribution of homicide to the decline of American cities. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, vol. 62, pp. 562–569. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPSON RJ and WILSON WJ, 1995. Toward a theory of race, crime, and urban inequality In Hagan J and Peterson R eds, Crime and Inequality. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- SAMPSON RJ, RAUDENBUSH SW and EARLS F, 1997. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, vol. 277, no. 5328, pp. 918–924. DOI 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPSON RJ, MORENOFF JD, and RAUDENBUSH SW, 2005. Social anatomy of racial and ethnic disparities in violence. American Journal of Public Health, vol. 95, no. 2, pp, 224–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMPSON RJ and WINTER AS, 2016. The racial ecology of lead poisoning: Toxic inequality in Chicago neighborhoods, 1995–2013. Du Bois Review, online, DOI: . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- SKOGAN WG 1990. Disorder and decline: Crime and the spiral of decay in American cities. New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- TOBLER W, 1970. A computer movie simulating urban growth in the Detroit region, Economic Geography, vol. 46, pp. 234–40. [Google Scholar]

- WALLER LA and GOTWAY, 2004. Applied Spatial Statistics for Public Health Data. New Jersey: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- WILDER CS, 2000. Vulnerable people, undesirable places A covenant with color: race and social power in Brooklyn. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS and COLLINS, 2001. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports, vol. 116, no.5, pp. 404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOODS LL, SHAW-RIDLEY M and WOODS CA, 2014. Can health equity coexist with housing inequalities? A contemporary issue in historical context. Health Promotion Practice, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 476–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]