Abstract

Objective:

Heavy drinking is common among smokers and is associated with especially poor health outcomes. Varenicline may affect mechanisms and clinical outcomes that are relevant for both smoking cessation and alcohol use. The current study examines whether varenicline, relative to nicotine replacement therapy, yields better smoking cessation outcomes among binge drinking smokers.

Method:

Secondary data analyses of a comparative effectiveness randomized controlled trial of three smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (12 weeks of varenicline, nicotine patch, or nicotine patch and lozenge) paired with six counseling sessions were conducted. Adult daily cigarette smokers (N = 1,078, 52% female) reported patterns of alcohol use, cigarette craving, and alcohol-related cigarette craving at baseline and over 4 weeks after quitting. Smoking cessation outcome was 7-day biochemically confirmed point-prevalence abstinence.

Results:

Binge drinkers had higher relapse rates than moderate drinkers at 4-week post-target quit day but not at the end of treatment or long-term follow up (12 and 26 weeks). Varenicline did not yield superior smoking cessation outcomes among binge drinkers, nor did it affect alcohol use early in the quit attempt. Varenicline did produce relatively large reductions in alcohol-related cigarette craving and overall cigarette craving during the first 4 weeks after quitting.

Conclusions:

Varenicline did not yield higher smoking abstinence rates or reduce alcohol use among binge drinkers. Varenicline did reduce alcohol-related cigarette craving but this did not translate to meaningful differences in smoking abstinence. Varenicline’s effects on smoking abstinence do not appear to vary significantly as a function of drinking status.

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death and disease in the United States. Co-use of tobacco and alcohol is very common, and a significant proportion of smokers report frequent heavy or binge drinking (43%–56%; McKee et al., 2007). The consequences of couse include increased risk for poor health outcomes including synergistic carcinogenic effects (for review, see McKee & Weinberger, 2013). The co-occurrence of heavy drinking and smoking heightens relapse risk for either substance; heavy drinkers typically have worse smoking cessation outcomes, and smoking is a risk factor for alcohol use relapse (Cook et al., 2012; Kahler et al., 2014; Leeman et al., 2007, 2008; McKee & Weinberger, 2013). The heightened health risks and poor smoking cessation outcomes produced by conjoint heavy drinking and smoking argue for research that develops especially effective interventions for this population (Yardley et al., 2015).

Alcohol consumption before and after a quit attempt is implicated in smoking cessation failure (Humfleet et al., 1999; Sherman et al., 1996; Smith et al., 1999). For instance, smoking cessation clinical trials have shown that post-quit drinking precipitates smoking relapse (Kahler et al., 2010; Shiffman, 1982; Shiffman et al., 1996), and laboratory studies have shown that alcohol administration acutely increases cigarette craving and decreases resistance to smoke (Dermody & Hendershot, 2017; Verplaetse & McKee, 2017). Alcohol’s effects on cigarette craving may constitute a mechanism via which alcohol use increases smoking relapse risk.

Varenicline has been proposed as a possible targeted treatment for heavy drinking smokers (Roche et al., 2016). Varenicline is a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist (partial α4β2, full α7) that suppresses cigarette craving (West et al., 2008) and increases smoking abstinence (Cahill et al., 2013). Evidence from preclinical, human laboratory, clinical trial, and epidemiological studies suggests that varenicline may also affect mechanisms and outcomes relevant for alcohol use. Human laboratory studies have shown that varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration as well as alcohol-induced smoking among heavy drinking smokers (McKee et al., 2009; Roberts & McKee, 2018; Roberts et al., 2017; but see, Ray et al., 2013). Three Phase 2 randomized controlled trials examining varenicline as a treatment for alcohol use disorder (AUD) have produced somewhat inconsistent results. Specifically, across these studies in comparisons with placebo, varenicline produced both positive (Litten et al., 2013) and negative (de Bejczy et al., 2015) effects on clinical alcohol use outcomes. In one case, benefit was seen only in males (O’Malley et al., 2018). Although smoking cessation was not the target outcome of these trials, there was evidence in one trial that varenicline increased smoking abstinence rates relative to placebo (O’Malley et al., 2018). In a second trial (Litten et al., 2013), the effect of varenicline on alcohol use was greater among smokers who simultaneously reduced their cigarettes per day during treatment (Falk et al., 2015).

Three clinical trials have examined varenicline treatment for smoking in heavy drinking smokers (Fucito et al., 2011; Hurt et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2012). In an initial small pilot investigation (N = 30), Fucito and colleagues (2011) reported that extended pre-quit treatment with varenicline (before quitting: 4 weeks vs. 3 weeks of placebo + 1 week of varenicline) led to a reduction in alcohol craving before the target quit day. There was no active treatment comparison during the smoking cessation phase, because all participants received 4 weeks of active varenicline (43% overall biochemically confirmed smoking cessation at end of treatment). One small placebo-controlled study (N = 33) of smokers with alcohol abuse or dependence according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994), found that 12-week varenicline treatment increased biochemically confirmed smoking cessation rates at end of treatment relative to placebo (44% vs. 6%, respectively) but did not reduce heavy drinking days at the end of treatment (Hurt et al., 2018). Last, a double-blind, placebo-controlled smoking cessation trial (N = 64: Mitchell et al., 2012) of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers found that varenicline reduced the average number of cigarettes smoked per week after the target quit day during Weeks 3–12 of treatment, but point prevalence abstinence data were not reported from this trial. Varenicline also reduced the total number of drinks per week over Weeks 3–11. These studies were essential to demonstrate the safety and tolerability of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers. Yet, the small study samples and resulting lack of power, and a pattern of inconsistent results, do not permit strong inference about the effects of varenicline on smoking cessation among heavy drinkers.

The effort to develop personalized smoking cessation pharmacotherapy for heavy drinking smokers demands that varenicline be compared with other first-line interventions for smoking across a range of alcohol use groups (e.g., moderate, infrequent/nondrinkers). After all, virtually all smokers should be given pharmacotherapy (Fiore et al., 2008), even heavy drinkers; the key question is, which one? Differential associations between medication effects and drinking status variables could reveal, for instance, that varenicline is especially effective relative to nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) in a particular drinking population (e.g., heavy drinkers) but not others (nondrinkers, moderate drinkers). Last, prior research on heavy drinking smokers has not clearly established the effects of varenicline on proximal variables that might mediate its effects on smoking abstinence (e.g., suppression of either alcohol consumption or alcohol-induced craving for cigarettes; Yardley et al., 2015). Clarifying these potential treatment mechanisms could provide insight into the nature of drinking-related risk for smoking cessation failure and afford further refinement of the personalized medicine approach to smoking treatment.

The current study examines whether varenicline yields superior smoking cessation outcomes relative to NRTs for heavy drinking smokers. We conducted secondary data analyses of a large comparative effectiveness smoking cessation trial (Baker et al., 2016) to examine smoking cessation outcomes as well as possible influences on the cessation process by alcohol use status. First, we examined whether pre–target quit day binge drinking, relative to moderate drinking, decreased smoking abstinence rates at 4, 12 (end of treatment), and 26 weeks. Second, we examined whether varenicline improved smoking abstinence rates relative to NRTs among binge drinkers (vs. moderate drinkers). Third, we examined whether varenicline decreased alcohol use, particularly among binge drinkers, early during a smoking cessation attempt. Last, we examined whether varenicline decreased overall cigarette craving and alcohol-related cigarette craving during the early stages of a smoking cessation attempt.

Method

Participants

This study presents secondary data analysis from a comparative effectiveness trial of three smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (for protocol, see Baker et al., 2016). Participants were drawn from a sample of 1,086 smokers recruited via advertisements and media (n = 917) and from relapsed smokers who previously participated in the Wisconsin Smokers Health Study (n = 169; Piper et al., 2009). Participants who provided baseline information about alcohol consumption were included in the final sample for the current study (N = 1,078).

Eligibility criteria included daily smoking (≥5 cigarettes per day), age 18 or older, desire to quit smoking, not currently participating in smoking cessation treatment, exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) ≥ 4 ppm, no diagnosis of or treatment for psychosis in past 10 years, no moderately severe depression, and medically able to use all three smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (for full eligibility and CONSORT diagram, see Baker et al., 2016). There were no exclusion criteria related to alcohol use. Participants provided written informed consent. This research was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Treatment

Smokers were randomly assigned to varenicline (n = 422), nicotine patch (n = 239), or combination nicotine replacement therapy (C-NRT; nicotine patch + nicotine lozenge, n = 417) in a 12-week open-label smoking cessation trial. To increase statistical power for primary outcomes, varenicline and C-NRT groups were oversampled by design. Pharmacotherapy began on the target quit day for patch and C-NRT and 1 week before the target quit day for varenicline (for dosing and titration schedule, see Baker et al., 2016). All participants were offered six 15- to 20-minute counseling sessions (five in-person, one phone) based on clinical practice guidelines (Fiore et al., 2008).

Assessments

Demographics and smoking variables.

Participants completed baseline assessments of demographics, smoking history, current smoking, and tobacco dependence. Tobacco dependence was assessed with the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD; Fagerström, 2012) and the Brief Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM; Smith et al., 2010). The WISDM includes two subscales: Primary Dependence Motives (PDM) and Secondary Dependence Motives (SDM; Piper et al., 2008). The PDM assess the degree to which people’s smoking is heavy, automatic, out of control, and related to significant craving. The SDM assesses smokers’ auxiliary motives such as smoking to regulate affect (Piper et al., 2008).

Alcohol use history.

Drinker groups were determined by baseline self-report of past-year alcohol use quantity, frequency, and binge drinking frequency. We assessed alcohol use using categories recommended by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Task Force on Recommended Alcohol Questions (NIAAA, 2003). For frequency, we queried, “During the last 12 months, how often did you usually have any kind of drink containing alcohol? By a drink we mean half an ounce of absolute alcohol (e.g., a 12 ounce can or glass of beer or cooler, a 5 ounce glass of wine, or a drink containing 1 shot of liquor).” For quantity, we asked, “During the last 12 months, how many alcoholic drinks did you have on a typical day when you drank alcohol?” For binge drinking among males, we asked, “During the last 12 months, how often did you have 5 or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol within a two-hour period?” For binge drinking among females, we asked, “During the last 12 months, how often did you have 4 or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol within a two-hour period?”

Binge drinkers (n = 289, 27%) were defined as reporting a binge episode at least once per month in the past year. This categorization of binge drinker closely aligns with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration definition of binge drinkers (Curry et al., 2018). Moderate drinkers (n = 418, 38%) were defined as reporting any alcohol use at least once per month, but binge drinking less than once per month in the past year. Nondrinkers and infrequent drinkers were defined as reporting alcohol use less than once per month in the past year (n = 371, 34%).

We divided drinkers into three categories since previous research has shown distinct differences between moderate drinkers and non-/infrequent drinkers (Cook et al., 2012; Kahler et al., 2009) so that combining these two groups could muddy comparisons with binge drinkers. In exploratory analyses, we found that if we compared binge drinkers with a combined non-/infrequent drinker and moderate drinker group, no group differences in smoking outcomes were observed across follow-up. The three-group comparison did yield such differences, suggesting that it more accurately captured differences in drinking status as they related to smoking and alcohol use.

Participants reported alcohol-related problems (past 3 months) via the Short Inventory of Problems–Revised (SIP-2R; Miller et al., 1995). Participants completed a structured clinical interview to provide DSM-IV-Text Revision of lifetime and past-year diagnoses (NCS-R Composite International Diagnostic Interview; Kessler & Ustün, 2004). We focused on past-year and lifetime alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence. Participants also reported baseline past-week alcohol use (7-day Timeline Followback; Sobell & Sobell, 1992).

Ecological momentary assessment (EMA).

EMA was conducted via Interactive Voice Response (IVR) densely surrounding the target quit day. Participants completed three IVR calls daily for 3 weeks (7 days before quitting to 14 days after quitting) and every other day for 2 additional weeks (16–28 days after quitting). We focused on the EMA evening assessment (once/day) of alcohol use quantity and alcohol-related cigarette craving (yes or no) during each day and cigarette craving during the last 15 minutes (single item, scale: 1 = not at all; 7 = extremely). Alcohol-related cigarette craving was assessed with the item, “Since you woke up, has anything happened that made you want to smoke?” (yes or no). A yes response was followed up with the item, “Did you drink alcohol?” (yes or no).

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of the main clinical trial was 7-day biochemically confirmed (via expired CO ≤5 ppm) point-prevalence abstinence at 26 weeks. For secondary analyses, we also evaluated smoking cessation outcomes early (4 weeks) and at the end of treatment (12 weeks).

Analysis plan

We analyzed dichotomous and continuous outcomes in a series of generalized and general linear models (GLMs, binomial logit), respectively, with between-subjects factors for alcohol use history and treatment. For smoking cessation outcomes, we dummy coded alcohol use history using moderate drinkers as the reference group, as previous research has demonstrated worse outcomes for both binge and non-/ infrequent drinkers (Cook et al., 2012; Kahler et al., 2009). For alcohol-related outcomes, we coded alcohol use history with orthogonal contrasts to examine drinkers (the means of both moderate and binge) versus non-/infrequent drinkers and binge versus moderate drinkers to evaluate the effects of regular exposure (vs. no/minimal) to any alcohol in addition to specific effects of intermittent heavy episodic use (i.e., bingeing). For treatment we examined varenicline versus other (mean patch and C-NRT) and included the orthogonal contrast of patch versus C-NRT. For exploratory follow-up analyses we further evaluated the effects of varenicline versus patch, to examine outcomes of varenicline compared with the standard control treatment condition. To examine treatment effects specifically among binge drinkers (as opposed to the differential effects between drinker groups), we conducted follow-up analyses with binge drinkers only. For planned orthogonal contrasts, we used centered and unit-weighted between-subjects regressors. We report odds ratios (ORs) for dichotomous outcomes and raw GLM parameter estimates (b) for continuous outcomes to document effect sizes. We used the standard p < .05 criteria for determining that results from all tests are significantly different from those expected if the null hypothesis were correct. We accomplished data analysis with R version 3.5 (R Development Core Team, 2018) within RStudio (RStudio Team, 2018).

Smoking cessation outcomes were CO-confirmed (<5 ppm) 7-day self-reported point prevalence (smoking = 0; abstinent = 1) at 4, 12, and 26 weeks. Participants who did not provide outcome information were assumed to be smoking (i.e., missing = smoking). We used IVR responses to quantify alcohol use outcomes and alcohol-related craving during the first 4 weeks following the target quit day. We defined alcohol-related cigarette craving both dichotomously (incidence: none = 0; any alcohol-related cigarette craving over the 4-week period = 1) and continuously (frequency: total number of days reported alcohol-related cravings). For comparison and to determine effect specificity, we evaluated average cigarette craving (not alcohol-related) via IVR during 4 weeks after the target quit day. We conducted sensitivity analyses in which we quantified alcohol use outcomes with multiple measures to evaluate convergence and robustness across quantification approaches; these include percentage of heavy drinking days, percentage any drinking days, mean drinks per day, and mean drinks per drinking day.

Results

Group characteristics

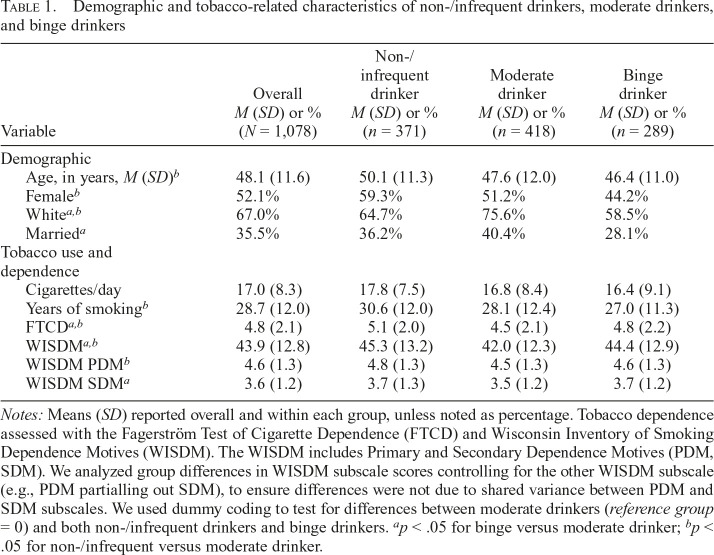

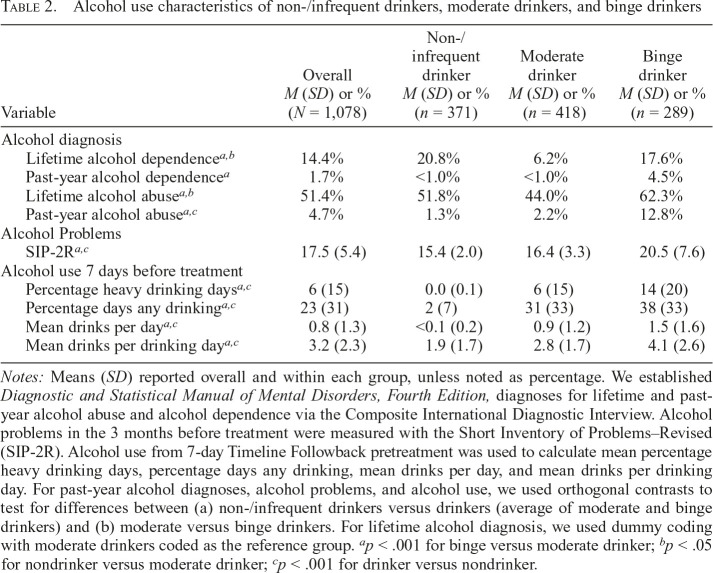

Participant demographics and tobacco use characteristics are displayed in Table 1. FTCD and WISDM tobacco dependence measures were higher for both non-/infrequent and binge drinkers than for moderate drinkers. Relative to moderate drinkers, non-/infrequent drinkers reported higher WISDM-PDM (partialling out WISDM-SDM), whereas binge drinkers reported higher WISDM-SDM (partialling out WISDM-PDM). The alcohol use groups were defined by past-year alcohol use to reflect more stable patterns of drinking. We also examined drinking during 1-week pretreatment (7-day Timeline Followback, see Table 2) as a validity check to confirm that the past-year–based groupings were consistent with alcohol use patterns in the week immediately before treatment. Relative to non-/infrequent drinkers, drinkers (combined moderate or binge drinkers) reported a higher percentage of drinking days, heavy drinking days, mean number of drinks per day, and mean number of drinks per drinking day. Likewise, binge drinkers reported greater alcohol use on these indicators than moderate drinkers. Furthermore, alcohol-related problems (SIP-2R) and past-year DSM-IV alcohol abuse were higher among drinkers than non-/infrequent drinkers, and higher among binge than moderate drinkers. However, lifetime diagnoses of alcohol dependence and abuse were higher among both non-/infrequent drinkers and binge drinkers relative to moderate drinkers, suggesting that a substantial portion of current nondrinkers were in sustained remission.

Table 1.

Demographic and tobacco-related characteristics of non-/infrequent drinkers, moderate drinkers, and binge drinkers

| Variable | Overall M (SD) or % (N = 1,078) | Non-/ infrequent drinker M (SD) or % (n = 371) | Moderate drinker M (SD) or % (n = 418) | Binge drinker M (SD) or % (n = 289) |

| Demographic | ||||

| Age, in years, M (SD)b | 48.1 (11.6) | 50.1 (11.3) | 47.6 (12.0) | 46.4 (11.0) |

| Femaleb | 52.1% | 59.3% | 51.2% | 44.2% |

| Whitea,b | 67.0% | 64.7% | 75.6% | 58.5% |

| Marrieda | 35.5% | 36.2% | 40.4% | 28.1% |

| Tobacco use and dependence | ||||

| Cigarettes/day | 17.0 (8.3) | 17.8 (7.5) | 16.8 (8.4) | 16.4 (9.1) |

| Years of smokingb | 28.7 (12.0) | 30.6 (12.0) | 28.1 (12.4) | 27.0 (11.3) |

| FTCDa,b | 4.8 (2.1) | 5.1 (2.0) | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.8 (2.2) |

| WISDMa,b | 43.9 (12.8) | 45.3 (13.2) | 42.0 (12.3) | 44.4 (12.9) |

| WISDM PDMb | 4.6 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.3) | 4.5 (1.3) | 4.6 (1.3) |

| WISDM SDMa | 3.6 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.2) | 3.7 (1.2) |

Notes: Means (SD) reported overall and within each group, unless noted as percentage. Tobacco dependence assessed with the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) and Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM). The WISDM includes Primary and Secondary Dependence Motives (PDM, SDM). We analyzed group differences in WISDM subscale scores controlling for the other WISDM subscale (e.g., PDM partialling out SDM), to ensure differences were not due to shared variance between PDM and SDM subscales. We used dummy coding to test for differences between moderate drinkers (reference group = 0) and both non-/infrequent drinkers and binge drinkers.

p < .05 for binge versus moderate drinker;

p < .05 for non-/infrequent versus moderate drinker.

Table 2.

Alcohol use characteristics of non-/infrequent drinkers, moderate drinkers, and binge drinkers

| Variable | Overall M (SD) or % (N = 1,078) | Non-/ infrequent drinker M (SD) or % (n = 371) | Moderate drinker M (SD) or % (n = 418) | Binge drinker M (SD) or % (n = 289) |

| Alcohol diagnosis | ||||

| Lifetime alcohol dependencea,b | 14.4% | 20.8% | 6.2% | 17.6% |

| Past-year alcohol dependencea | 1.7% | <1.0% | <1.0% | 4.5% |

| Lifetime alcohol abusea,b | 51.4% | 51.8% | 44.0% | 62.3% |

| Past-year alcohol abusea,c | 4.7% | 1.3% | 2.2% | 12.8% |

| Alcohol Problems | ||||

| SIP-2Ra,c | 17.5 (5.4) | 15.4 (2.0) | 16.4 (3.3) | 20.5 (7.6) |

| Alcohol use 7 days before treatment | ||||

| Percentage heavy drinking daysa,c | 6.(15) | 0.0 (0.1) | 6.(15) | 14.(20) |

| Percentage days any drinkinga,c | 23.(31) | 2.(7) | 31.(33) | 38.(33) |

| Mean drinks per daya,c | 0.8 (1.3) | <0.1 (0.2) | 0.9 (1.2) | 1.5 (1.6) |

| Mean drinks per drinking daya,c | 3.2 (2.3) | 1.9 (1.7) | 2.8 (1.7) | 4.1 (2.6) |

Notes: Means (SD) reported overall and within each group, unless noted as percentage. We established Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, diagnoses for lifetime and past-year alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence via the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Alcohol problems in the 3 months before treatment were measured with the Short Inventory of Problems–Revised (SIP-2R). Alcohol use from 7-day Timeline Followback pretreatment was used to calculate mean percentage heavy drinking days, percentage days any drinking, mean drinks per day, and mean drinks per drinking day. For past-year alcohol diagnoses, alcohol problems, and alcohol use, we used orthogonal contrasts to test for differences between (a) non-/infrequent drinkers versus drinkers (average of moderate and binge drinkers) and (b) moderate versus binge drinkers. For lifetime alcohol diagnosis, we used dummy coding with moderate drinkers coded as the reference group.

p < .001 for binge versus moderate drinker;

p < .05 for nondrinker versus moderate drinker;

p < .001 for drinker versus nondrinker.

Smoking cessation outcomes

Alcohol use history.

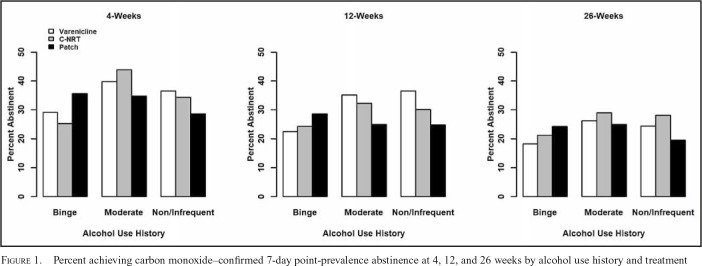

There was a significant main effect of alcohol use history for 4-week abstinence, p = .011 (Supplemental Table S1). (Supplemental material appears as an online-only addendum to this article on the journal’s website.) Contrasts indicate that smoking cessation rates were significantly lower for binge drinkers (29.4%) than for moderate drinkers (40.2%), OR = 1.53, 95% CI [1.10, 2.13], p = .011, but there was not a significant difference between non-/infrequent drinkers (34.0%) and moderate drinkers, OR = 1.31, 95% CI [0.97, 1.79], p = .082. However, although the pattern was descriptively consistent across the time, the effects of alcohol use history on smoking cessation were not statistically significant at 12 weeks, p = .078, or 26 weeks, p = .155. Neither contrast (vs. moderate drinkers) was statistically significant at either 12 or 26 weeks.

Smoking cessation results remained similar when we used a more stringent criterion for categorizing binge drinkers defined as reporting binge drinking at least one day per week. This definition is similar to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration definition of heavy drinker as someone who engages in binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month. Specifically, there remained a significant main effect of alcohol use history on smoking cessation at 4 weeks, p = .007, driven by a significant difference between weekly binge (25.5%) versus moderate (38.7%) drinkers, OR = 1.82, 95% CI [1.21, 2.79], p = .005. To evaluate the robustness of these results, we further examined whether smoking cessation rates showed similar patterns among participants with past-year DSM-IV alcohol abuse diagnosis. Consistent with the pattern of results when defined by past-year binge drinking, we found a significant main effect of past-year DSM-IV alcohol abuse on smoking cessation at 4 weeks, p = .042, but not at 12 or 26 weeks (ps > .05). Smoking cessation rates at 4 weeks were lower among participants with a diagnosis of alcohol abuse in the past year (21.6%) than no alcohol abuse (35.7%), OR = 0.49, 95% CI [0.24, 0.94], p = .042. Essentially, with these sensitivity analyses we obtained the same pattern of results with these different measures of alcohol use or diagnoses.

Treatment effects.

As previously reported, there was not a significant main effect of treatment condition on 4-, 12-, or 26-week point-prevalence abstinence (Baker et al., 2016). Further, alcohol use history and treatment condition did not interact significantly at any time point (Figure 1), suggesting that treatments were not differentially effective overall as a function of baseline alcohol use (ps > .28). Exploratory analyses showed that gender did not significantly moderate the relations between treatment and alcohol group with abstinence at any time point. Given our focus on varenicline as a potential targeted treatment for binge drinking smokers, we examined the varenicline group with the combined patch and C-NRT groups contrast by alcohol use history interactions. There was not a significant interaction at any time point between varenicline versus combined patch and C-NRT and the contrast of either the non-/infrequent drinker or binge drinker groups with the moderate drinker group (ps > .05). Furthermore, among binge drinkers (dummy coded, binge drinker = 0), we did not observe differential treatment effects of varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT groups) at any time point (ps > .05). Post hoc exploratory analyses were conducted to determine whether varenicline would exert relatively stronger effects amongst binge drinkers when it is compared with the patch-only condition. Results revealed the same pattern of effects as were obtained with the combined comparison group (patch and C-NRT).

Figure 1.

Percent achieving carbon monoxide–confirmed 7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 4, 12, and 26 weeks by alcohol use history and treatment

Alcohol use outcomes

Treatment effects.

There was neither a significant main effect of treatment nor an interaction between treatment and alcohol use history at 4 weeks after quitting on percentage of heavy drinking days, percentage any drinking days, mean drinks per day, or mean drinks per drinking day (ps > .05). We conducted focused follow-up analysis of treatment effects on alcohol use outcomes amongst binge drinkers only (dummy coded, binge drinker = 0). Among binge drinkers, there was no significant effect of varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT) on these four alcohol use indicators (ps > .05).

We conducted follow-up analyses to examine if sex (contrast coded male = +0.5, female = -0.5) interacted with alcohol use history or treatment for any alcohol use outcome. There was not a significant interaction between sex and treatment or sex and treatment and alcohol use history on percentage heavy drinking days, percentage any drinking days, or mean drinks per drinking day. There was a significant interaction with sex and treatment and alcohol use history on mean drinks per drinking day, F(4, 548) = 2.44, p = .046. However, follow-up tests of two- or three-way interactions with sex and specific contrasts of treatment and alcohol use history did not yield any significant interactions on mean drinks per day, suggesting that the overall three-way interaction was not driven by particularly robust effects.

Alcohol-related cigarette craving

Alcohol use history.

There was a significant main effect of alcohol use history on the incidence of alcohol-related cigarette craving, p < .001. Contrasts indicate that alcohol-related cigarette craving was reported by significantly more drinkers (41.2%) than non-/infrequent drinkers (20.8%), OR = 2.73, 95% CI [1.83, 4.13], p < .001, and by more binge drinkers (46.9%) than moderate drinkers (37.1%), OR = 1.60, 95% CI [1.04, 2.47], p = .033. There was also a significant main effect of alcohol use history on the frequency of alcohol-related cigarette craving, F(2, 1069) = 10.91, p < .001. Contrasts indicate that alcohol-related cigarette craving was reported more frequently by drinkers than nondrinkers, b = 0.30, t(1068) = 4.55, p < .001, but there was no difference between binge versus moderate drinkers, b = 0.06, t(1068) = 0.80, p = .422.

To evaluate the specificity to alcohol-related craving, we analyzed overall mean cigarette craving (not alcohol related) during the 4 weeks after quit day. There was not a significant main effect of alcohol use history on mean craving in the unadjusted model, nor when adjusted for 1-week pre-quit craving (ps >.3).

Treatment effects.

Treatment exerted no significant overall main effects on the incidence, χ2(2, 604) = 4.85, p = .088, or frequency, F(2, 1069) = 2.29, p = .101, of alcohol-related cigarette craving. However, exploratory contrasts reveal that there was a significant effect of varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT) on the incidence of alcohol-related cigarette craving, OR = 0.63, 95% CI [0.43, 0.92], p = .019. Contrasts indicate that alcohol-related cigarette craving was reported by significantly fewer smokers using varenicline (28.4%) than patch (37.0%) and C-NRT (37.1%). Similarly, there was a significant effect of varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT) on the frequency of alcohol-related cigarette craving, b = 0.15, t(1068) = 2.50, p = .015, indicating that such craving was reported less often by smokers using varenicline. However, these effects did not differ as a function of alcohol use history as varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT) did not interact significantly with either the drinker versus the non-/infrequent drinker contrast or the binge versus moderate drinker contrast (ps > .05).

We conducted follow-up tests adjusting for post-quit craving (not alcohol induced) on the effect of varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT) on the incidence and frequency of alcohol-induced cigarette craving. Consistent with unadjusted models, the effect of varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT) remained significant for both the incidence, OR = 0.65, 95% CI [0.44, 0.95], p = .026, and frequency, b = 0.14, t(977) = 2.13, p = .033, of alcohol-induced cigarette craving. This suggests that varenicline reduces alcohol-induced cigarette craving over and above its general effects on cigarette craving.

To evaluate the specificity to alcohol-related craving we analyzed overall mean cigarette craving (not alcohol related). There was a significant main effect of treatment on overall craving, F(2, 978) = 7.87, p < .001. Contrasts indicate that mean craving was lower among smokers using varenicline (vs. combined patch and C-NRT), b = 0.33, t(978) = 3.09, p = .002, and lower among smokers using C-NRT (vs. patch), b = 0.41, t(978) = 3.02, p = .003. The varenicline effect appears to be driven primarily by a significant difference compared to patch, b = 0.53, t(978) = 3.94, p < .001. However, the treatment effects (overall and specific contrasts) did not differ as a function of alcohol use history (ps > .05). In the model adjusted for pre-quit craving, there is not a significant effect of varenicline (vs. combined patch-NRT/C-NRT), b = 0.17, t(950) = 1.79, p = .073. However, there remains a significant contrast of C-NRT versus patch, b = 0.39, t(950) = 3.31, p < .001, and varenicline versus patch, b = 0.36, t(950) = 3.07, p = .022.

Discussion

Consistent with prior research (Cook et al., 2012), binge drinkers relapsed at higher rates early (at 4 weeks) in their smoking cessation attempts than did moderate drinkers, but this effect was not statistically significant at 12 and 26 weeks. Contrary to expectations, varenicline did not yield superior smoking cessation outcomes relative to NRTs among binge drinkers. This pattern of results was consistent across several sensitivity analyses using different indices of risky drinking including monthly and weekly binge drinking and past-year DSM-IV alcohol abuse diagnosis, increasing confidence in the robustness of this finding. In addition, varenicline (vs. NRTs) did not decrease alcohol use early in the quit attempt. However, varenicline did reduce both overall cigarette craving and alcohol-related cigarette craving (vs. patch), although this effect did not vary reliably with drinking history.

The current study was motivated by increasing interest in the field that varenicline may be a promising, targeted smoking cessation treatment for heavy drinking smokers (Fucito et al., 2011; Hurt et al., 2018; Roche et al., 2016). However, varenicline (vs. patch) did not produce significantly better smoking cessation outcomes for monthly binge drinkers in the current sample. Prior studies on this topic had various limitations including relatively small sample sizes, use of a treatment duration control condition, and a primary focus on alcohol-related outcomes (Fucito et al., 2011; Hurt et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2012). These trials have demonstrated the initial safety and acceptability of varenicline in smokers who drink heavily. However, our failure to detect differential smoking cessation outcomes for binge drinkers in a much larger sample relative to two active NRT comparisons does not support the value of alcohol use variables in a treatment assignment algorithm for varenicline.

Varenicline (vs. patch) reduced the incidence of alcohol-related cigarette craving as well as the intensity of cigarette craving in general in the current study. The latter finding suggests that the effects on alcohol-related craving may have less to do with alcohol-targeted action (e.g., via impaired executive function, cross cue conditioning). Rather it may be more parsimonious to conclude that varenicline is simply very effective at reducing craving. The ecological validity of these results is enhanced by real-world measurement via EMA; however, the phrasing and timing (once daily) of the assessment items do not permit definitive causal inference regarding whether participants reported cigarette craving in response to drinking versus drinking in response to cigarette craving. Thus, although the EMA data demonstrate an association between alcohol use and craving, the lack of temporal specificity does not permit inference of a causal association between drinking and craving. Evidence from human laboratory studies with heavy drinking smokers, which permit stronger causal inferences than these EMA data, have demonstrated that the effects of varenicline (vs. placebo) on cigarette craving are similar before and after alcohol administration in controlled settings (Roberts et al., 2018; also see Ray et al., 2014).

Furthermore, the effect of varenicline on alcohol-related craving was not selective for binge drinkers in the current study. Most importantly, although varenicline did influence real-world daily reports of cigarette craving, including alcohol-related cigarette craving, this did not translate into superior clinical outcomes (i.e., smoking cessation). However, it is the case that varenicline’s suppression of alcohol-related craving remained significant even when its effects on craving in general were statistically controlled, suggesting that it may especially affect alcohol-related motivational states (although this could be due to third variables associated with alcohol use, such as cigarette availability). Although craving consistently shows a meaningful relation with smoking relapse, it is only one of many putative pathways through which interventions may lead to improved cessation outcomes.

Similarly, varenicline did not affect alcohol use patterns early in a smoking cessation attempt overall or specifically among binge drinking smokers. This is possibly not surprising, as participants were not selected in this smoking cessation trial on the basis of a desire or goal to reduce their drinking; although smokers were counseled to moderate their alcohol use in the service of their smoking cessation goals. Previous research suggests that varenicline’s effects on alcohol use are likely modest at best, in both smoking cessation clinical trials (Fucito et al., 2011; Hurt et al., 2018; Mitchell et al., 2012) and AUD treatment clinical trials (de Bejczy et al., 2015; Litten et al., 2013; O’Malley et al., 2018).

Limitations and future directions

These were post hoc, secondary, non-preregistered analyses; therefore, warranted concerns include increased experiment-wise error and capitalizing on fortuitous associations (Nosek et al., 2018). Of course, the results of this research are largely negative. Also, this comparative effectiveness trial does not permit comparison to a placebo or no-treatment control condition. The nicotine patch has been found to reduce subjective intoxication to alcohol (McKee et al., 2008), so it is important to recognize that varenicline is being compared in these analyses with a treatment that itself may have significant alcohol-related effects. However, the current study was designed to address the question of if one type of pharmacotherapy is more beneficial (varenicline vs. NRT) rather than if pharmacotherapy may be beneficial (vs. placebo) for binge drinking smokers.

Smokers in the parent clinical trial (Baker et al., 2016) were not specifically selected for heavy drinking. However, even without targeted recruitment of heavy drinking smokers, a sizable portion of participants reported regular binge drinking. Different results might have been obtained if risk were categorized by AUD diagnosis or other risky drinking criteria (e.g., NIAAA hazardous drinking criteria, WHO risk levels; Falk et al., 2019; O’Malley et al., 2018; Witkiewitz et al., 2017). However, this study comprised too few participants who met DSM-IV criteria for current alcohol dependence to allow such analyses. As such, the results of the current analyses may not generalize to smokers with AUD. There remain a multitude of competing classification systems and definitions of heavy drinking across professional organizations and federal agencies; future efforts should continue to aim to identify and harmonize the optimal categorization to inform both research and clinical practice (Curry et al., 2018).

The EMA assessment was intended to evaluate the influence of alcohol use on eliciting cigarette craving but does not permit definitive causal inferences due to lack of temporal sequencing of drinking and cigarette craving. Although EMA findings are consistent with the possibility of reflecting alcohol-induced craving, it is also possible that they instead reflect drinking in response to cigarette craving or co-occurring alcohol use and cigarette craving within the same days. Future research with more focused EMA items and denser sampling of intensive longitudinal real-world assessments is needed to clarify the temporal ordering (and possible causal associations) of alcohol use and cigarette craving.

The analyses presented in this article were conducted using data from a parent randomized clinical trial in which varenicline did not produce a statistically significant effect on smoking abstinence at follow-up relative to the nicotine patch (Baker et al., 2016). This null finding is at variance with a considerable body of other research (Cahill et al., 2013; Fiore et al., 2008). Different results might have been obtained if varenicline had been more effective in the parent trial; however, even in the absence of a significant effect of varenicline (vs. patch and C-NRT) on smoking abstinence, it is possible that varenicline might have been especially effective in certain subgroups. Last, the parent trial was adequately powered to detect treatment main effects but there was less power to test moderation effects. As such, only large moderator effects were likely to be detected.

Conclusions

Binge drinking smokers relapsed at higher rates early in their smoking cessation attempt than did moderate drinkers, but this difference decayed over time. This highlights the early phase of smoking cessation as a particularly high relapse risk period for binge drinkers (Cook et al., 2012). Varenicline did not lead to differential smoking cessation outcomes for binge drinkers relative to other drinking categories, nor did it affect alcohol use early in the quit attempt. Varenicline reduced both overall cigarette craving and alcohol-related cigarette craving (vs. NRT), although these effects were not selective to binge drinkers. Thus, the results of the current study do not suggest that varenicline is an especially effective smoking cessation treatment for smokers with more risky alcohol use patterns. Confidence in these null results is enhanced by the large sample size and consistency of results using multiple definitions of heavy drinking. Of course, these results do not mean that varenicline should not be used with smokers who drink heavily; they merely mean that varenicline’s benefits are not moderated by patterns of binge drinking. Future research might examine whether varenicline exerts differential effects when smokers are stratified on different drinking status variables (e.g., presence vs. absence of AUD) or combined with other targeted pharmacotherapy (e.g., varenicline and naltrexone; see Ray et al., 2014; Roberts et al., 2018).

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant 5R01HL109031 and National Cancer Institute Grant K05CA139871 to the University of Wisconsin Center for Tobacco Research and Intervention. JTK and ALJ are supported by Advanced Fellowships from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. JWC is also supported by Merit Review Award 101CX00056 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. The funding bodies had no part in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors have received no direct or indirect funding from, nor do they have a connection with, the tobacco, alcohol, pharmaceutical or gaming industries or anybody substantially funded by one of these organizations. All authors report no conflict of interest. Clinical Trials Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01553084; https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01553084

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baker T. B., Piper M. E., Stein J. H., Smith S. S., Bolt D. M., Fraser D. L., Fiore M. C. Effects of nicotine patch vs varenicline vs combination nicotine replacement therapy on smoking cessation at 26 weeks: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315:371–379. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.19284. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.19284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill K., Stevens S., Perera R., Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: An overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;5:CD009329. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook J. W., Fucito L. M., Piasecki T. M., Piper M. E., Schlam T. R., Berg K. M., Baker T. B. Relations of alcohol consumption with smoking cessation milestones and tobacco dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:1075–1085. doi: 10.1037/a0029931. doi:10.1037/a0029931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S. J., Krist A. H., Owens D. K., Barry M. J., Caughey A. B., Davidson K. W., Wong J. B. the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;320:1899–1909. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.16789. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.16789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bejczy A., Löf E., Walther L., Guterstam J., Hammarberg A., Asanovska G., Söderpalm B. Varenicline for treatment of alcohol dependence: A randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2015;39:2189–2199. doi: 10.1111/acer.12854. doi:10.1111/acer.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody S. S., Hendershot C. S. A critical review of the effects of nicotine and alcohol coadministration in human laboratory studies. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41:473–486. doi: 10.1111/acer.13321. doi:10.1111/acer.13321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K. Determinants of tobacco use and renaming the FTND to the Fagerström Test for Cigarette Dependence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2012;14:75–78. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr137. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D. E., Castle I.-J. P., Ryan M., Fertig J., Litten R. Z. Moderators of varenicline treatment effects in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial for alcohol dependence: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2015;9:296–303. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000133. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk D. E., O’Malley S. S., Witkiewitz K., Anton R. F., Litten R. Z., Slater M., Fertig J. & the Alcohol Clinical Trials Initiative (ACTIVE) Workgroup. Evaluation of drinking risk levels as outcomes in alcohol pharmacotherapy trials: A secondary analysis of 3 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:374–381. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3079. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C., Jaen C. R., Baker T. B., Bailey W. C., Benowitz N. L., Curry S. J.et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update—Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fucito L. M., Toll B. A., Wu R., Romano D. M., Tek E., O’Malley S. S. A preliminary investigation of varenicline for heavy drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2011;215:655–663. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2160-9. doi:10.1007/s00213-010-2160-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet G., Muñoz R., Sees K., Reus V., Hall S. History of alcohol or drug problems, current use of alcohol or marijuana, and success in quitting smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00057-4. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt R. T., Ebbert J. O., Croghan I. T., Schroeder D. R., Hurt R. D., Hays J. T. Varenicline for tobacco-dependence treatment in alcohol-dependent smokers: A randomized controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2018;184:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.017. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C. W., Borland R., Hyland A., McKee S. A., Thompson M. E., Cummings K. M. Alcohol consumption and quitting smoking in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;100:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.006. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C. W., Metrik J., Spillane N. S., Day A., Leventhal A. M., McKee S. A., Rohsenow D. J. Acute effects of low and high dose alcohol on smoking lapse behavior in a laboratory analogue task. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:4649–4657. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3613-3. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3613-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler C. W., Spillane N. S., Metrik J. Alcohol use and initial smoking lapses among heavy drinkers in smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:781–785. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq083. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Ustün T. B. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. doi:10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman R. F., Huffman C. J., O’Malley S. S. Alcohol history and smoking cessation in nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion sustained release and varenicline trials: A review. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2007;42:196–206. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agm022. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agm022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman R. F., McKee S. A., Toll B. A., Krishnan-Sarin S., Cooney J. L., Makuch R. W., O’Malley S. S. Risk factors for treatment failure in smokers: Relationship to alcohol use and to lifetime history of an alcohol use disorder. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1793–1809. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443742. doi:10.1080/14622200802443742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten R. Z., Ryan M. L., Fertig J. B., Falk D. E., Johnson B., Dunn K. E., Stout R. & the NCIG (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Clinical Investigations Group) Study Group. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy of varenicline tartrate for alcohol dependence. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2013;7:277–286. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829623f4. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829623f4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee S. A., Falba T., O’Malley S. S., Sindelar J., O’Connor P. G. Smoking status as a clinical indicator for alcohol misuse in US adults. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167:716–721. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.716. doi:10.1001/archinte.167.7.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee S. A., Harrison E. L. R., O’Malley S. S., Krishnan-Sarin S., Shi J., Tetrault J. M., Balchunas E. Varenicline reduces alcohol self-administration in heavy-drinking smokers. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:185–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee S. A., O’Malley S. S., Shi J., Mase T., Krishnan-Sarin S. Effect of transdermal nicotine replacement on alcohol responses and alcohol self-administration. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:189–200. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0952-3. doi:10.1007/s00213-007-0952-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee S. A., Weinberger A. H. How can we use our knowledge of alcohol-tobacco interactions to reduce alcohol use? Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013;9:649–674. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185549. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W., Tonigan J., Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse (Project MATCH Monograph Series) (NIH Publication No. 95-3911) Vol. 4. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. M., Teague C. H., Kayser A. S., Bartlett S. E., Fields H. L. Varenicline decreases alcohol consumption in heavy-drinking smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2012;223:299–306. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2717-x. doi:10.1007/s00213-012-2717-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Recommended alcohol questions. 2003 Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions.

- Nosek B. A., Ebersole C. R., DeHaven A. C., Mellor D. T. The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2018;115:2600–2606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708274114. doi:10.1073/pnas.1708274114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley S. S., Zweben A., Fucito L. M., Wu R., Piepmeier M. E., Ockert D. M., Gueorguieva R. Effect of varenicline combined with medical management on alcohol use disorder with comorbid cigarette smoking: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:129–138. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3544. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper M. E., Bolt D. M., Kim S.-Y., Japuntich S. J., Smith S. S., Niederdeppe J., Baker T. B. Refining the tobacco dependence phenotype using the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:747–761. doi: 10.1037/a0013298. doi:10.1037/a0013298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper M. E., Smith S. S., Schlam T. R., Fiore M. C., Jorenby D. E., Fraser D., Baker T. B. A randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:1253–1262. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.142. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2018. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Ray L. A., Courtney K. E., Ghahremani D. G., Miotto K., Brody A., London E. D. Varenicline, low dose naltrexone, and their combination for heavy-drinking smokers: Human laboratory findings. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:3843–3853. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3519-0. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3519-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray L. A., Lunny K., Bujarski S., Moallem N., Krull J. L., Miotto K. The effects of varenicline on stress-induced and cue-induced craving for cigarettes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.015. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W., Harrison E. L. R., McKee S. A. Effects of varenicline on alcohol cue reactivity in heavy drinkers. Psychopharmacology. 2017;234:2737–2745. doi: 10.1007/s00213-017-4667-9. doi:10.1007/s00213-017-4667-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W., McKee S. A. Effects of varenicline on cognitive performance in heavy drinkers: Dose-response effects and associations with drinking outcomes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2018;26:49–57. doi: 10.1037/pha0000161. doi:10.1037/pha0000161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts W., Shi J. M., Tetrault J. M., McKee S. A. Effects of varenicline alone and in combination with low-dose naltrexone on alcohol-primed smoking in heavy-drinking tobacco users: A preliminary laboratory study. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2018;12:227–233. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000392. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche D. J. O., Ray L. A., Yardley M. M., King A. C. Current insights into the mechanisms and development of treatments for heavy drinking cigarette smokers. Current Addiction Reports. 2016;3:125–137. doi: 10.1007/s40429-016-0081-3. doi:10.1007/s40429-016-0081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RStudio Team. RStudio. Integrated development environment for R. RStudio, Inc.; Boston, MA: RStudio; 2018. Retrieved from http://www.rstudio.org. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. E., Wang M. M., Nguyen B. Predictors of success in a smoking cessation clinic. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1996;11:702–704. doi: 10.1007/BF02600163. doi:10.1007/BF02600163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Relapse following smoking cessation: A situational analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:71–86. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.1.71. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.50.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S., Paty J. A., Gnys M., Kassel J. A., Hickcox M. First lapses to smoking: Within-subjects analysis of real-time reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:366–379. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.366. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. M., Kraemer H. C., Miller N. H., DeBusk R. F., Taylor C. B. In-hospital smoking cessation programs: Who responds, who doesn’t? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:19–27. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.1.19. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.67.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith S. S., Piper M. E., Bolt D. M., Fiore M. C., Wetter D. W., Cinciripini P. M., Baker T. B. Development of the Brief Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:489–499. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq032. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntq032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell L. C., Sobell M. B. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R. Z., Allen J. P., editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biochemical methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Verplaetse T. L., McKee S. A. An overview of alcohol and tobacco/nicotine interactions in the human laboratory. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2017;43:186–196. doi: 10.1080/00952990.2016.1189927. doi:10.1080/00952990.2016.1189927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West R., Baker C. L., Cappelleri J. C., Bushmakin A. G. Effect of varenicline and bupropion SR on craving, nicotine withdrawal symptoms, and rewarding effects of smoking during a quit attempt. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1041-3. doi:10.1007/s00213-007-1041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K., Hallgren K. A., Kranzler H. R., Mann K. F., Hasin D. S., Falk D. E., Anton R. F. Clinical validation of reduced alcohol consumption after treatment for alcohol dependence using the World Health Organization risk drinking levels. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41:179–186. doi: 10.1111/acer.13272. doi:10.1111/acer.13272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley M. M., Mirbaba M. M., Ray L. A. Pharmacological options for smoking cessation in heavy-drinking smokers. CNS Drugs. 2015;29:833–845. doi: 10.1007/s40263-015-0284-5. doi:10.1007/s40263-015-0284-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]