Abstract

Hairy cell leukemia variant (HCLv), described 30 years ago, was reported to present with high disease burden and less often leukopenia, and later was reported to be resistant to purine analogs. Patients with HCLv were overrepresented among patients with HCL seeking relapsed/refractory trials. To compare clinical and molecular features of classic HCL (HCLc) and HCLv, 85 rearrangements expressing immunoglobulin variable heavy chain were sequenced, taken from 20 patients with HCLv and 62 with HCLc. The gene VH4–34, commonly used in autoimmune disorders, was found in eight patients (40%) with HCLv versus six (10%) with HCLc (p = 0.004). Ninety-three percent of the VH4–34 rearrangements were unmutated, defined as >98% homologous to the germline sequence. Clinical features of VH4–34+ patients that were similar to those with HCLv included higher white blood cell counts at diagnosis (p = 0.002) and lower response (p = 0.00001) and progression-free survival (p = 0.007) after first-line cladribine, and shorter overall survival from diagnosis (p < 0.0001). It was found that VH4–34 was independent from HCLv and a stronger predictor than HCLv in associating with poor prognosis. We conclude that VH4–34+ hairy cell leukemia, which only partly overlaps with HCLv, is associated with poor prognosis after single-agent cladribine. However, cases are observed which respond well to antibody therapy either alone or in combination with purine analog.

Keywords: Immunoglobulin rearrangement, HCL, HCLv, VH4–34, IGHV4–34

Diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia variant

Cawley et al. in 1980 reported a B-cell disorder similar to classic hairy cell leukemia (HCLc) which stained for tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and had ‘hairy’ cytoplasmic projection, but less neutropenia and more circulating malignant cells [1]. In contrast to the excellent outlook for patients with HCLc, particularly after purine analog therapy, patients with hairy cell leukemia variant (HCLv) have a relatively poor response to treatment and also shorter overall survival [2]. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized HCLv as a disease distinct from HCLc. HCLv is defined by: cytohematologic features (leukocytosis, monocytes, prominent nucleoli, blastic/convoluted nuclei, and/or absence of circumferential shaggy contours), variant immunophenotype (absence of CD25, annexin A1, or TRAP), and resistance to conventional HCL therapy [3]. Other HCLc-related markers usually absent in HCLv include CD123, CD24, and HC2. CD103 is usually positive in HCLc and HCLv but can be negative in HCLv [4], although CD103-negative HCL should suggest splenic marginal zone lymphoma/splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes (SMZL or SLVL), particularly if CD11c is negative or dim.

Molecular characterization of classic hairy cell leukemia and hairy cell leukemia variant

As in other B-cell malignancies as well as in normal B-cells, the malignant cells have one or occasionally two rearrangements expressing immunoglobulin heavy chain, taken from one each of several variable (IGHV), diversity (IGHD), and junctional (IGHJ) genes. For even more diversity in IGH sequence, and to bind more avidly to antigen, the IGH sequence may undergo somatic hypermutation. The resulting IGH sequences are monoclonal and unique for each patient. We previously took advantage of this specificity by designing a real-time quantitative polmerase chain reaction (RQ-PCR) assay that used sequence-specific primers and probe [5]. Compared to conventional PCR used to detect minimal residual disease (MRD) in HCL using consensus primers, the RQ-PCR assay was far more sensitive, able to detect a hairy cell diluted in 106 normal cells [5]. We previously reported a study of 24 IGH rearrangements in 20 patients with HCLc and three with HCLv [6], and compared results to 70 rearrangements in 69 patients reported by other investigators. Most patients had significant frequencies of somatic hypermutation (SHM), with a mean homology to germline of 93.9% [6]. The SHMs were analyzed for whether they replaced the amino acid (R) or were silent (S), and whether replacement mutations occurred in the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) more than in framework regions (FRs). Several patients were identified with a low probability of mutations being random (p = 0.001–0.003), hence suggestive of antigen-driven mutation. In that study, two patients were VH4–34+, both unmutated, defined as >98% homology to the germline sequence, and both presented with elevated tumor burden, like HCLv, but only one of the two patients had HCLv based on immunophenotype [6]. Other reports included several VH4–34+ patients with HCL, including two unmutated HCLv cases out of 38 [7], and five HCLc cases out of 83, three of which were unmutated [8]. The following will review a more recently published study associating VH4–34+ HCL with presenting features and prognosis, and will include previously unpublished clinical observations in several of these patients [9].

Variable heavy gene usage in classic hairy cell leukemia versus hairy cell leukemia variant

To determine VH usage of the expressed VDJ rearrangement in the patients with HCL, total RNA was prepared from HCL cells using either PAXgene tubes if the HCL clone was prominent relative to normal B-cells, or CD11c-sorted HCL cells that were obtained from heparinized blood by Ficoll centrifugation [9]. A total of 22 rearrangements were analyzed from 20 patients with HCLv and 63 from 62 with HCLc. A total of 30 different VH genes were cloned. In HCLc, the most common VH genes were VH3–23 (n = 13, 21%), VH4–34 (n = 6, 10%), and VH3–30 (n = 5, 8%). In HCLv, the most common VH genes were VH4–34 (n = 8, 36%), and then VH4–39 and VH4–61 (each n = 2, 9%). Thus, while VH4–34 was the second most commonly used gene in HCLc, the largest usage difference between HCLc and HCLv was with VH4–34 (p = 0.007).

Degree of homology to germline VH in classic hairy cell leukemia versus hairy cell leukemia variant

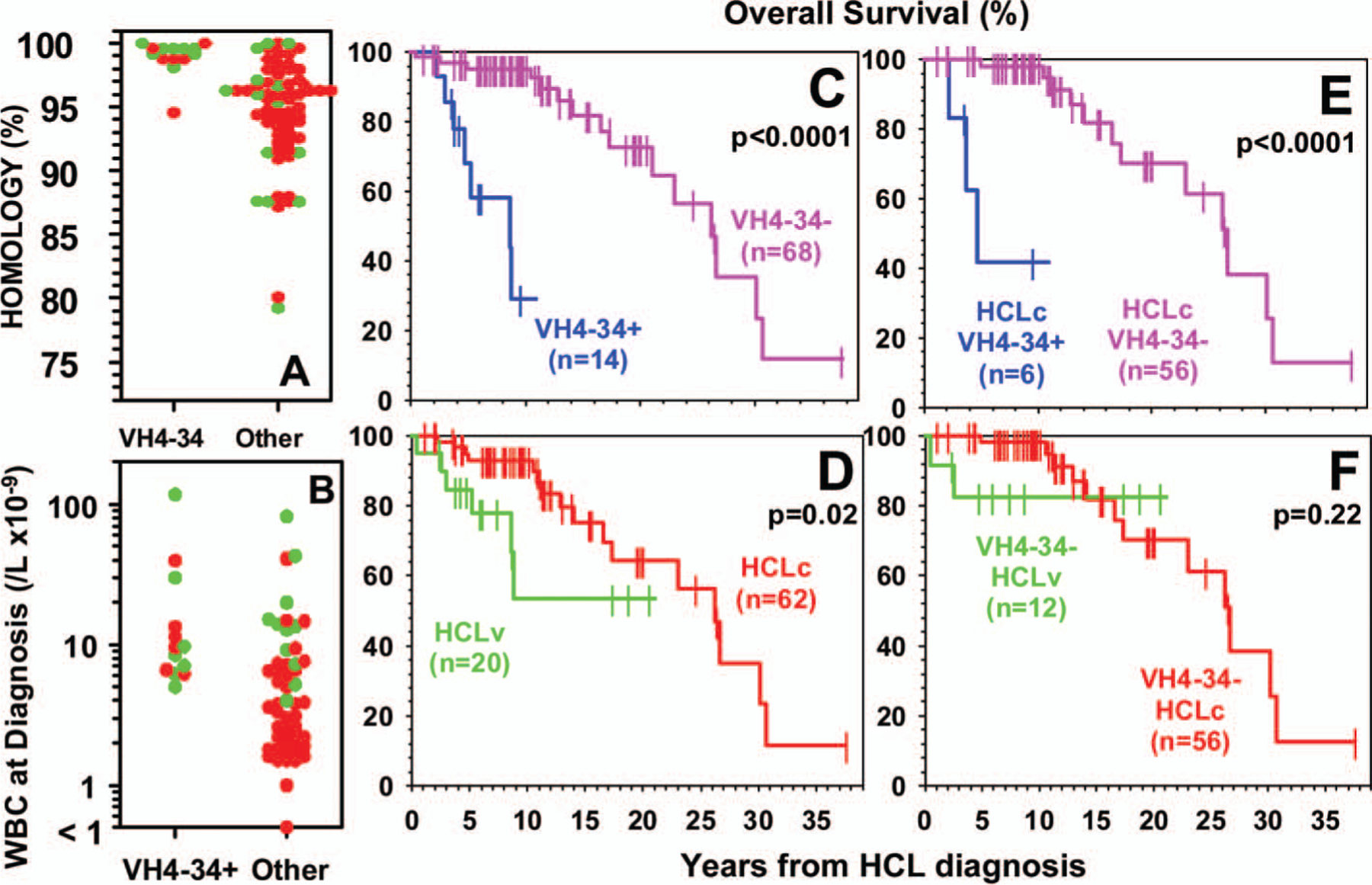

To determine whether the mutation frequency differed by HCLc vs. HCLv, or by VH gene usage, the cloned sequences were compared to the closest germline sequence on the ImMunoGeneTics (IMGT) database [9]. As shown in Figure 1(A), 13 (93%) out of 14 VH4–34+ rearrangements were unmutated, compared to 11 (15%) out of 71 of the others (p = 4 × 10−8). The median homology to germline was 99.4% vs. 95.6% for VH4–34 positive vs. negative rearrangements, and the homologies were significantly different by rank order (Wilcoxon) analysis (p < 0.0001). As can be seen in Figure 1(A), there was no difference in homology between HCLv and HCLc (median 97.6% vs. 95.9%, respectively, p = 0.12), or in frequency of unmutated sequences. Thus, VH4–34+ HCL rearrangements had high homology to the germline sequence unrelated to whether HCLv or HCLc.

Figure 1.

(A) Homology to germline sequence for HCLv (green) or HCLc (red) rearrangements based on VH4–34 status. (B) White blood cell counts at diagnosis for patients with HCLv (green) or HCLc (red) based on VH4–34 status. (C–F) Overall survival in patients with respect to VH4–34 status and variant phenotype. (C, D) Data for all 82 patients with respect to VH4–34 (C) or variant (D) status, (E) data for only patients with HCLc, (F) data for only VH4–34-negative patients.

Clinical factors prior to treatment in classic hairy cell leukemia and hairy cell leukemia variant, with respect to VH4–34 status

Since leukopenia at presentation is common with HCLc but less so with HCLv [1,2], blood counts at presentation were analyzed for all patients where relevant information was available. As shown in Figure 1(B), absence of leukopenia, defined as a white blood cell count of ≥5 × 109/L, was more common in VH4–34+ than -negative patients (93% vs. 40%, p = 0.0006), and also more common in HCLv than in HCLc (83% vs. 40%, p = 0.002). These significant differences were still observed when patients with HCLv were subtracted from the comparison of VH4–34+ and VH4–34-negative cases (100% vs. 32%, p = 0.002). As shown in Figure 1(B), by rank order analysis, presenting white blood cell counts were higher for VH4–34+ versus -negative patients (median 9.0 vs. 3.8 ×109/L, p = 0.002). Although the same was true of HCLv vs. HCLc (median 11.3 vs. 3.5 × 109/L, p < 0.0001), among just patients with classic disease, VH4–34 positivity correlated independently with presenting white blood cell count (p = 0.003). Moreover, absence of leukopenia was more common in HCLv than HCLc even after VH4–34+ cases were subtracted (80% vs. 32%, p = 0.01), indicating that HCLv and VH4–34 correlated independently with lack of leukopenia. Median neutrophils (2.23 vs. 0.82 × 109/L, p = 0.004) and platelets (105 vs. 68 × 109/L, p = 0.014) were also higher at presentation in VH4–34+ than in other patients with HCL, although differences became non-significant once HCLv cases were subtracted [9]. In contrast, higher median neutrophil (5.52 vs. 0.71 × 109/L, p = 0.0001) and platelet (136 vs. 61 × 109/L, p = 0.004) counts at presentation were observed in HCLv compared to HCLc even after VH4–34 cases were subtracted. Thus, VH4–34 positivity was independently associated with higher white blood cells at presentation but not higher neutrophils or platelets, suggesting that VH4–34+ patients have the misfortune of higher malignant cells in the blood without higher normal blood cells.

Response to treatment and outcome with respect to VH4–34 status

To determine whether VH4–34 status was associated with clinical outcomes, the response to first-line cladribine was assessed when possible, and survival data from diagnosis were obtained on all 82 patients. Failure of first-line cladribine was much more frequent overall than expected due to the skewed patient population examined, since patients were mainly seeking relapsed/refractory trials. Among just patients with HCLc, the overall response rate (ORR) was much lower for VH4–34+ than -negative patients (33% vs. 90%, p = 0.006). Among VH4–34-negative patients, ORR was lower with HCLv than with HCLc (50% vs. 90%, p = 0.02), indicating that VH4–34 and HCLv were independently related to lack of response. With respect to overall survival from diagnosis, Figures 1(C) and 1(D) indicate that either VH4–34 (p < 0.0001) or HCLv (p = 0.02) correlates with poor outcome. As shown in Figure 1 (E), among patients with HCLc, overall survival (OS) from diagnosis was much shorter for VH4–34+ than -negative patients (4.7 vs. 26.64 years, p < 0.0001). However, as shown in Figure 1(F), among VH4–34-negative patients, HCLv was not associated with significantly shorter survival compared to HCLc (21.05 vs. 17.33 years, p = 0.22). Thus, VH4–34 positivity correlates with poor overall survival in HCL, and the lower survival attributed to HCLv may in part be due to the abundance of VH4–34+ patients within the HCLv population.

Possible mechanisms for poor prognosis with VH4–34+ hairy cell leukemia

VH4–34 is expressed in a variety of other hematologic malignancies, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) where it was reported in 159 (8%) of 1967 rearrangements. It was second most common after VH1–69 [10]. However, in CLL, only 33 (21%) out of the 159 VH4–34 rearrangements were unmutated, very different from 13 out of 14 patients with HCL (p = 9 × 10−8). VH4–34 is also used by 5–10% of normal B-cells [11] and B-cells mediating autoimmune disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, cold agglutinin disease, and multiple sclerosis. It is possible that VH4–34-expressing B-cells can evade checkpoints that might normally keep normal B-cells from either recognizing self-antigens, or becoming malignant. It is notable that multiple myeloma is almost never VH4–34+, possibly because transformation to this malignancy occurs late in the timeline of B-cell differentiation, and before that point, VH4–34+ B-cells might undergo clonal deletion or anergy [12].

Effective treatment for VH4–34+ hairy cell leukemia and hairy cell leukemia variant

In our series, unmutated VH4–34+ HCL was associated with failure of initial cladribine therapy in all cases, when given as a single agent. However, several case reports document that rituximab alone can induce complete remission (CR) in HCLv. As shown in Table I, we have also observed frequent complete remissions in patients treated with monoclonal antibody (mAb)-based therapy, including BL22 [13,14] and also the combination of rituximab and cladribine (CDAR) [15]. We believe it is potentially valuable to determine the molecular status of patients with HCL, and also to develop new therapies for patients who have recognized poor-prognosis variants.

Table I.

Complete remission (or clearing of bone marrow biopsy with resolutions of blood counts) achieved by immunotherapy with or without chemotherapy for HCLv or VH4–34+ HCL.

| Patient ID | VH | Diagnosis | Treatment* | Open clinical trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL14 | VH4–31 | HCLv | BL22 | 07-C-0130 |

| BL18 | VH4–34 | HCLv | BL22 | 07-C-0130 |

| BL26 | VH4–34 | HCLv | BL22 | 07-C-0130 |

| BH32 | VH4–34 | HCLc | BL22 | 07-C-0130 |

| RG01 | Unknown | HCLv | CDAR | 09-C-0005 |

| RG02 | Unknown | HCLv | CDAR | 09-C-0005 |

| RG04 | VH4–34 | HCLv | CDAR | 09-C-0005 |

HA22, also called CAT-8015 or moxetumomab pasudotox, is a higher-affinity version of BL22 which is now undergoing testing for HCL, protocol 07-C-0130.

HCLv, hairy cell leukemia variant; HCLc, classic hairy cell leukemia; CDAR, cladribine + rituximab.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute, Intramural Program. A portion of this research was originally published in Blood by Arons et al. (see ref 9).

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at www.informahealthcare.com/lal.

References

- 1.Cawley JC, Burns GF, Hayhoe FG. A chronic lymphoproliferative disorder with distinctive features: a distinct variant of hairy-cell leukaemia. Leuk Res 1980;4:547–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matutes E, Wotherspoon A, Brito-Babapulle V, Catovsky D. The natural history and clinico-pathological features of the variant form of hairy cell leukemia. Leukemia 2001;15:184–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. , editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Lyon: IARC; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matutes E, Wotherspoon A, Catovsky D. The variant form of hairy-cell leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 2003;16: 41–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arons E, Margulies I, Sorbara L, et al. Minimal residual disease in hairy cell leukemia patients assessed by clone-specific polymerase chain reaction. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:2804–2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arons E, Sunshine J, Suntum T, Kreitman RJ. Somatic hypermutation and VH gene usage in hairy cell leukemia. Br J Haematol 2006;133:504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin-Jimenez P, Garcia-Sanz R, Gonzalez D, et al. Molecular characterization of complete and incomplete immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements in hairy cell leukemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 2007;7:573–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Forconi F, Sozzi E, Rossi D, et al. Selective influences in the expressed immunoglobulin heavy and light chain gene repertoire in hairy cell leukemia. Haematologica 2008;93: 697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arons E, Suntum T, Stetler-Stevenson M, Kreitman RJ. VH4–34+ hairy cell leukemia, a new variant with poor prognosis despite standard therapy. Blood 2009;114:4687–4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray F, Darzentas N, Hadzidimitriou A, et al. Stereotyped patterns of somatic hypermutation in subsets of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: implications for the role of antigen selection in leukemogenesis. Blood 2008;111:1524–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brezinschek HP, Foster SJ, Brezinschek RI, Dorner T, Domiati-Saad R, Lipsky PE. Analysis of the human VH gene repertoire. Differential effects of selection and somatic hypermutation on human peripheral CD5(+)/IgM+ and CD5(−)/IgM+ B cells. J Clin Invest 1997;99:2488–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rettig MB, Vescio RA, Cao J, et al. VH gene usage in multiple myeloma: complete absence of the VH4.21 (VH4–34) gene. Blood 1996;87:2846–2852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kreitman RJ, Wilson WH, Bergeron K, et al. Efficacy of the anti-CD22 recombinant immunotoxin BL22 in chemotherapy-resistant hairy-cell leukemia. N Engl J Med 2001;345: 241–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreitman RJ, Stetler-Stevenson M, Margulies I, et al. Phase II trial of recombinant immunotoxin RFB4(dsFv)-PE38 (BL22) in patients with hairy cell leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 2983–2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravandi F, Jorgensen JL, O’Brien SM, et al. Eradication of minimal residual disease in hairy cell leukemia. Blood 2006;107:4658–4662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]