Abstract

Double network theory is extended to include guest-host interactions, enabling injectability and cytcompatibility of tough hydrogels. Non-covelent interactions are used as a sacraficial network to toughen covalently crosslinked hydrogels formed from hyaluronic acid. Shear-thinning of supramolecular bonds allows hydrogel injection and rapid self-healing, while gentle reaction conditions permit cell encapsulation with high viability.

Keywords: double network, supramolecular chemistry, biomaterials, tissue engineering

Graphical Abstract

Hydrogels are an invaluable class of materials for biomedical applications, owing to their utility as structural, bioinstructive, and cell-laden implants[1]. Despite their many positive attributes, covalently crosslinked hydrogels are typically brittle, and supramolecular assemblies often exhibit pseudoplastic deformation with low resistance to loading. Thus, each individually fails to recapitulate biological tissues’s resilience toward repeated loading. Addressing these limitations, double network (DN) hydrogels[2], a subset of specifically structured interpenetrating networks that exhibit resistance to mechanical failure, have evolved to produce desirable mechanical properties for biomedical applications[3, 4]. Canonically, the primary network (formed first) is highly crosslinked and brittle to dissipate energy and protect the ductile secondary network from rupture.[5, 6] Remarkably, this mechanism has recently enabled the formation of hydrogels with strengths approaching those of synthetic rubbers and connective tissues[4, 6, 7].

Despite their improved mechanical properties, DNs are susceptible to the Mullins effect[8, 9], a loss of mechanical strength upon loading, due to permanent rupture of covalent bonds. Physical networks, including those based on ionic crosslinking (e.g., polyampholytes[10], alginate[11, 12], and chitin[13]) as well as hydrogen bonding[14], have been introduced to attain recoverable primary networks within DN hydrogels. However, recovery remains poor, requiring long timeframes (>30min) or excessive heating (>50°C) to approach initial properties. Moreover, the processing techniques common to the fabrication of DN hydrogels require lengthy sequential polymerizations where often toxic secondary network components are swollen into the first network[2] or secondary ionic crosslinking is similarly induced[10, 13, 14]. Some efforts have been taken to overcome these limitations and encapsulate viable cells within IPN’s, such as by orthogonal click reactions[15] or multistep photopolymerization[13, 16, 17]; however, such methodologies preclude injection.

To simultaneously address the need for rapid self-healing, injectable delivery, and cytocompatibility, we have established a novel and generalizable methodology for formation of DN hydrogels by tandem supramolecular interactions and secondarily formed covalent crosslinks. Supramolecular guest-host assembly[18, 19] was utilized to develop a rapidly self-healing primary network, where β-cyclodextrin (CD, host) was chosen as the host macrocyle due to its demonstrated biocompatibility, ease of chemical modification[20], and high affinity guest-host complexation (Keq ~ 105 M−1)[21] with adamantane (Ad, guest). Standard anhydrous esterification and amidation reactions (Supplementary Information, Scheme S1) were utilized to couple 1-adamantane acetic acid and aminated CD to hyaluronic acid (HA), used due to its long history of use in biomedical applications and potential for functional modification[22]. Upon mixing of the separate polymer solutions (5.0 wt% overall), a guest-host (GH) hydrogel formed (Figure 1a) that exhibited expected frequency dependent moduli due to the dynamic bond structure (Figure 1b) and yielded at high strain (>75% reduction in G’) with recovery (>95%) within 6 seconds of removal of high strain conditions (Figure 1c). Thus, GH complexation was successfully leveraged in construction of a primary network that formed upon simple mixing, was shear-yielding, and underwent rapid self-healing.

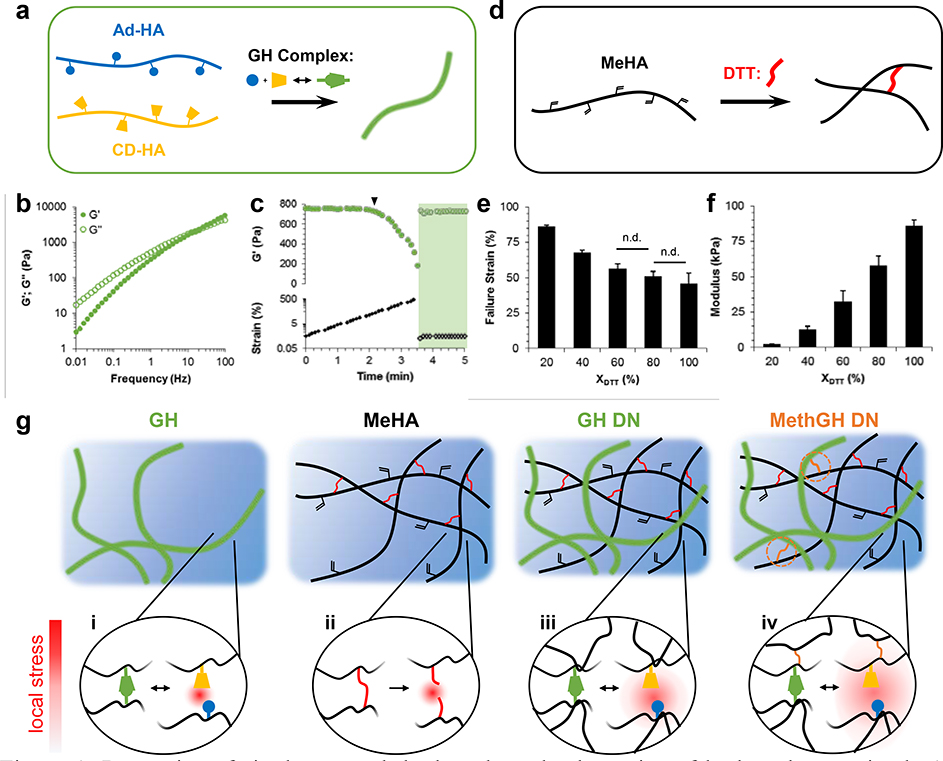

Figure 1.

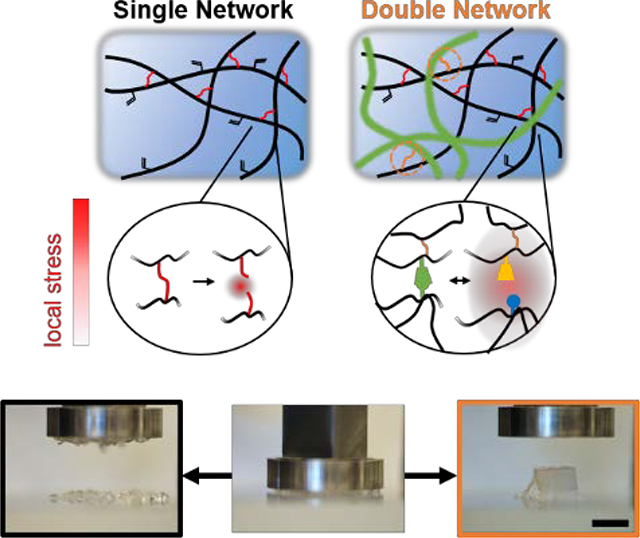

Properties of single network hydrogels and schematics of hydrogels examined. a) Schematic of adamantane (Ad-HA, blue) and β-cyclodextrin (CD-HA, yellow) modified hyaluronic acid crosslinked through guest-host (GH) complexation. b-c) GH hydrogels (5.0 wt%) were examined by frequency sweeps (b; 0.01–100 Hz, 0.5% strain) and strain sweeps (c; 1.0 Hz, 0.5–500% strain) with yield point indicated (▼, 64% strain) and subsequent rapid recovery (shaded; 1.0 Hz, 0.5% strain). d-f) Schematic of Michael addition crosslinking (d) of methacrylated hyaluronic acid (MeHA) by dithiothreitol (DTT, red), where crosslink density was controlled through the thiol:methacrylate ratio (ΧDTT) and altered failure strains (e) and compressive elastic moduli (f). (p < 0.05, except where no difference (n.d.) is indicated). g) Network architectures examined included a guest-host (GH) hydrogel, covalently crosslinked (MeHA) hydrogel, guest-host double network (GH DN), and methacrylated guest-host double network (MethGH DN). Local stress under loading (red) dissipated through reversible GH complex rupture (i) within the primary GH network; increased stress led to covalent bond rupture (ii) within the secondary covalent network, whereas energy dissipation from the GH network reversibly protected the secondary MeHA network from bond rupture within the double networks (iii), a mechanism which was enhanced through network tethering to enable stress transference (iv).

The secondary network was formed through an orthogonal covalent crosslinking reaction. Specifically, methacrylated HA (3.0 wt% Me100HA, Supplementary Information, Scheme 2) was reacted with dithiothreitol (DTT) to form a covalently crosslinked hydrogel under basic conditions (50 mM TEOA, pH 8) via Michael addition between methacrylates and thiols (Figure 1d). Addition crosslinking enabled facile changes in the covalent crosslink density by adjusting the ratio of thiol to methacrylate (ΧDTT), resulting in a network with tunable properties. Failure strains and elastic moduli were achieved ranging from 45.5±0.5 to 86.5±7.6 % and 2.2±0.2 to 85.7±4.5 kPa, respectively (Figure 1e,f). All subsequent analyses utilized ΧDTT = 20%, due to requisite ductility of the secondary network.

The combination of supramolecular and covalent chemistries enabled the engineering and investigation of DN hydrogels with unique and desirable properties (Figure 1g), including injectability and self-healing (due to reversible guest-host crosslinking) and easily tunable properties (due to covalent crosslinking). The guest-host double network (GH DN) was readily formed upon one-pot mixing of the polymer solutions, owing to simultaneous and orthogonal crosslinking mechanisms, with interpenetration of the two networks resulting in stress transference primarily through network entanglement[23]. Since network tethering may enhance overall network properties[24], the polymers were modified (Supporting Information, Scheme S2 and S3) to incorporate methacrylates into the GH network (MethGH DN), enabling coupling of the two interpenetrating networks. Under compressive loading (Figure 2a, Movie 1 in Supporting Information) MeHA hydrogel controls with only covalent crosslinking exhibited dramatic and sudden failure, attributed to unhindered propagation of covalent rupture points[8, 25]; GH DN hydrogels exhibited ductile and unrecoverable failure, attributed to covalent bond rupture and subsequent sliding of entanglement points and GH complexes[9]; MethGH DN hydrogels demonstrated exceptional recovery with only minor and localized defects observed, likely arising from imperfections created during sample preparation. Due to the pseudoplastic behavior of GH single networks, they were not suitable for testing.

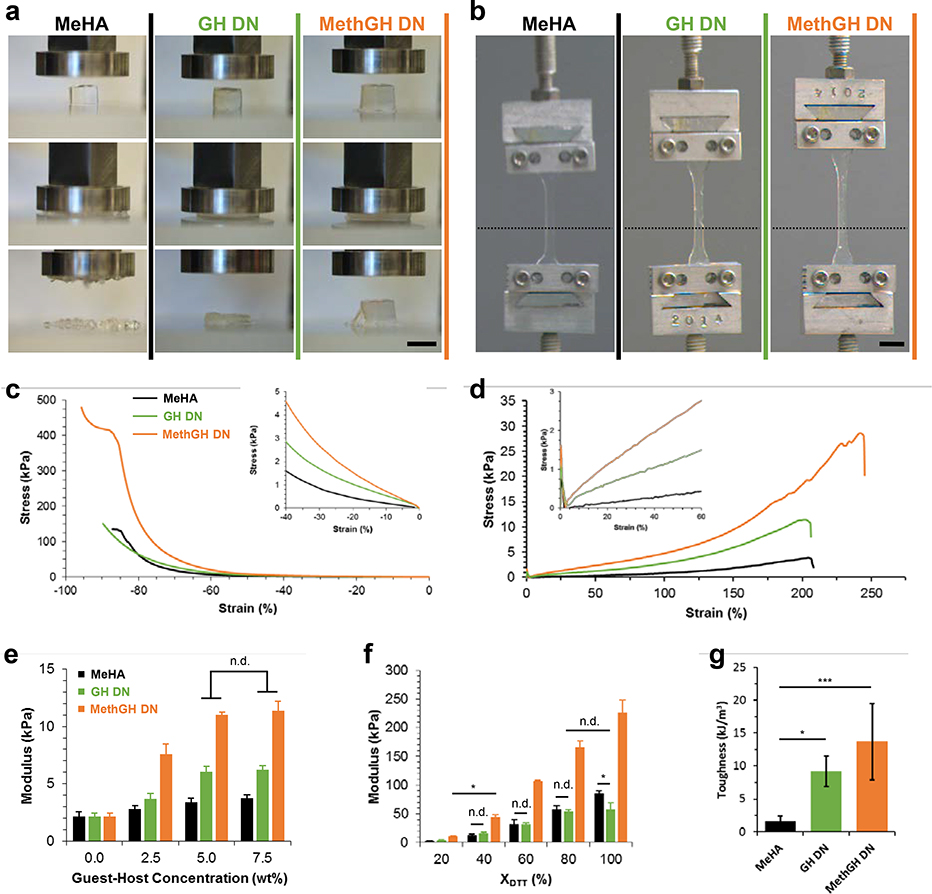

Figure 2.

Dependence of double network properties on structure and composition. a) Differing modes of compressive failure were observed between the hydrogels following compression to 90% strain (unconfined, 0.5 N min−1): brittle (MeHA: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%; left), ductile (GH DN: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% GH, middle), and recoverable (MethGH DN: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% MethGH, right). Scale bar: 5.0 mm. b) Tensile testing of identically composed samples demonstrated a high degree of elasticity, where starting position of the top member is indicated (dotted line). Scale bar: 1.0 cm. c-d) Corresponding compressive (c, 0.5 N min−1) and tensile (d, 5 mm sec−1) stress-strain relationships. e-g) Networks demonstrated tunable properties. e) Compressive elastic moduli with varied supramolecular guest-host density (3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 0–7.5 wt% GH), where MeHA groups contained soluble HA to account for contributions by polymer entanglement. (p < 0.01, within and between groups for both DNs except where no difference (n.d.) is indicated). f) Compressive elastic moduli with varied covalent crosslink density modulated by the ratio of thiol to methacrylate (3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20–100%, 5.0 wt% GH). (p < 0.01, for all comparisons except where indicated: *, p < 0.05; n.d., no difference). g) Tensile toughness for DNs and MeHA controls (*, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.005,).

Compressive stress-strain relationships (Figure 2c) illustrated increased moduli for DNs (inset), as well as substantially increased failure stresses for MethGH DN hydrogels. While properties were investigated at a nominal rate (0.5N min−1), compressive strain rate dependence was observed (Supporting Information, Figure S1) due to stochastic and forcefully induced GH complex yielding[19, 26], indicating shock absorbing capacity reminiscent of many load bearing tissues. Elastic moduli were dependent on polymer concentration of the GH network (Figure 2e). Since no significant improvements were observed with GH polymer concentrations greater than 5.0 wt%, this concentration was used in subsequent analyses. Hydrogel properties were highly tunable through modulation of covalent crosslink density (Figure 2f). MethGH DN moduli exhibited approximately a fivefold and threefold amplification at ΧDTT = 20% and 100%, respectively, far exceeding summation of network properties where the elastic moduli of GH and MethGH single network hydrogels were <1kPa (1.0 Hz, 0.5% strain, where E = 3(G’)). Enhancement of MethGH DN moduli resulted in greater failure stresses and toughness, despite similar failure strains (Supporting Information, Figure S2). Enhanced mechanical properties required an interpenetrating structure, but did not result from entanglement alone, as indicated by controls with purturbed polymer composition (Supporting Information, Figure S3).

Under tensile loading (Figure 2b,d, Movie 2 in Supporting Information) all hydrogels exhibited substantial elastic elongation with high failure strains (>150%, Supporting Information, Figure S4). Elastic moduli increased with GH DN formation and further improved with tethering in the MethGH DN (Figure 2d, Figure S4 in Supporting Information). For both DNs, failure stresses were also significantly improved over MeHA controls. As a result of these changes, both DNs exhibited drastic increases in toughness (Figure 2g, > 8.5 fold increase for MethGH DN).

In addition to enhancing mechanical strength, a distinctive and advantageous feature of supramolecular interactions is their ability to undergo repeated association to endow macrostructural and microstructural (i.e., internal) self-healing (Figure 3). Cut hydrogel fragments exhibited cohesion in aqueous conditions, which was disturbed only for MeHA hydrogels following mechanical agitation (Figure 3a, Movie 3 in Supporting Information). Cohesion likewise occurred between GH DN and MethGH DN hydrogel fragments, due to their identical guest-host composition. Notably, binding occurred rapidly (~1 sec, Movie 4 in Supporting Information), allowing near-immediate resistance to separation by repeated mechanical loading.

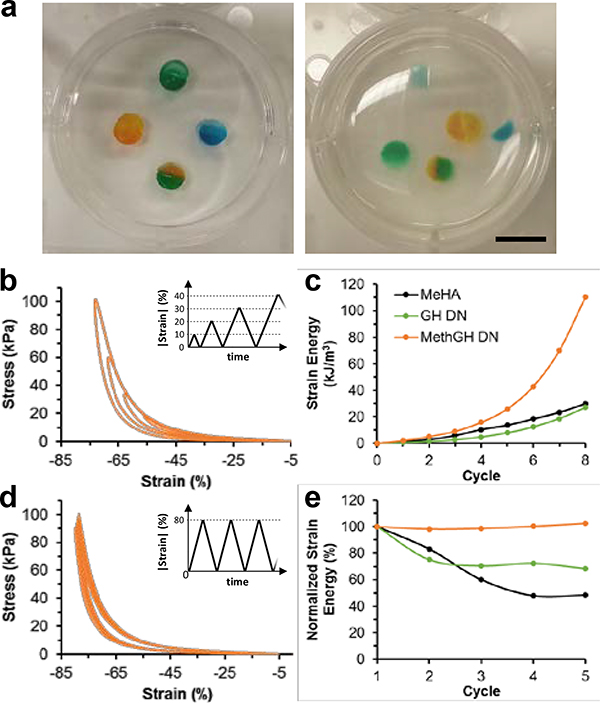

Figure 3.

Supramolecular self-healing at macroscopic and molecular scales. a) Macroscopic images of self-healing between fragments of MeHA (blue, 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%), GH DN (green, 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% GH), and MethGH DN (orange, 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% MethGH) hydrogels before (top) and after (bottom) mechanical agitation, which demonstrated a lack of self-healing between MeHA samples only. Scale bar: 1.0 cm. b-c) Compressive stress-strain profiles (b) for ramped loading (8 cycles at 0.5 N min−1 as shown, inset) of MethGH DN and strain energy of all groups (c). d-e) Compressive stress-strain profiles for repeated loading to 80% strain (5 cycles at 0.5 N min−1 as shown, inset) of MethGH DN (d) and normalized strain energy of all groups (e).

To quantitatively investigate internal self-healing of DNs, repetitive loading was examined. Stress-strain profiles under ramped cyclic compressive strain (20–70%, Figure 3b, Figure S5 in Supporting Information) demonstrated synchronization of the loading curves with no appreciable change in moduli between loading cycles, indicating elastic recovery below critical strains. An appreciable increase in the strain energy (i.e., the energy required to induce deformation) was observed for MethGH DN hydrogels (Figure 3c) with successive cycles. Moreover, the hysteresis energy (i.e., the energy consumed due to internal bond failure[8]) demonstrated a notable increase for MethGH DN hydrogels, relative to MeHA and GH DN groups, indicating energy dissipation due to forcefully induced GH complex failure. With repeated application of 80% maximum strain, Mullins-type softening (i.e., loss of moduli and strain energy) was observed in MeHA and GH DN hydrogels, which was not observed at subcritical (<70%) strains (Figure S6 in Supporting Information) or in MethGH DNs (Figure 3d-e). Thus, MethGH DNs effectively leverage the primary supramolecular network to prevent internal rupture of covalent bonds and maintain their moduli, even without lengthy recovery times that are needed with other types of crosslinking (e.g., ionic DNs)[10, 12, 13]. Taken together, results indicate that supramolecular bonds within DNs immediately self-heal between loading cycles and contribute substantially to energy consumption throughout loading, enabling supramolecular DNs to undergo repetitive loading in rapid succession, such as that which occurs in biological tissues.

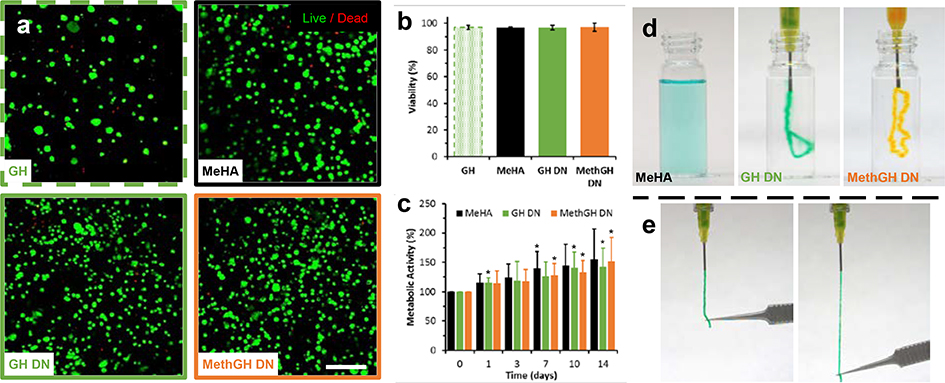

For biomedical applications, the encapsulation or delivery of cells is often desirable; however, these processes remain challenging with many types of crosslinking. Towards this, we developed cytocompatible crosslinking conditions (< 20 min, pH 8.5, 37°C) that supported tandem DN formation (Supporting Information, Figure S7), using a phosphine Michael addition catalyst (TCEP: tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine, 2.5mM). These crosslinking conditions and cell inclusion did not impact hydrogel mechanics (Supporting Information, Figure S8). At 24 hours following hydrogel formation (day 0), all hydrogels exhibited homogenous cell distributions, assessed by confocal microscopy (Figure 4a, Figure S9 in Supporting Information) and high viability (>95%, Figure 4b). Throughout 14 days in culture, metabolic activity (Figure 4c) remained similar between all hydrogel groups (p > 0.67, ANOVA) and increased over time, significant for GH DN beyond 7 days and for MethGH DN beyond 3 days, relative to group baseline. Corresponding temporal examination of hydrogel moduli, swelling, and degradation (Supporting Information, Figure S10) revealed that initial swelling (day 1) had minimal impact on hydrogel moduli. MethGH DN moduli were higher than that of the MeHA and GH DN hydrogels throughout the study and that DN groups edhibited reduced degradation. All hydrogels exhibited a nearly four-fold increase in mass due to swelling by day 1, which was maintained thereafter. Such high water content (> 97%) may reduce mechanical properties relative to conventionally formed DNs with higher polymer fractions; though, this likely helped overcome diffusive limitations that hindered long-term viability in other tough IPN and DN hydrogels[16]. At day 14, high viability (> 98%) and uniform cell distribution was maintained (Supporting Information, Figure S9, Movie 5).

Figure 4.

Cell encapsulation, distribution, and long-term viability. a) Confocal microscopy maximum projections of encapsulated mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs; calcein & ethidium staining) 24 hours after encapsulation within single (GH: 5.0 wt%; MeHA: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%) and double network (GH DN: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% GH; MethGH DN: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% MethGH) hydrogels. Of note, GH hydrogels exhibited a high degree of swelling, which reduced MSC density. Scale bar: 200 μm. b) High viability (> 95%) was observed for all hydrogels 24 hours after encapsulation (day 0), determined via quantification of epifluorescent images, and did not vary between groups (p > 0.95). c) Metabolic activity was similar across groups at all timepoints (p > 0.69) and increased over 14 days of culture (*p < 0.05 relative to baseline, repeated measures ANOVA with post hoc Student’s t-test). GH hydrogels are not included, as they were not maintained in long-term culture. d-e) Macroscopic images of hydrogels following injection into TEOA buffer (d), demonstrating diffusion of MeHA (3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%) prior to crosslinking and rapid supramolecular re-assembly of double network formulations (GH DN: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% GH; MethGH DN: 3.0 wt% Me100HA, ΧDTT = 20%, 5.0 wt% MethGH), which maintained elasticity (e, GH DN) following covalent crosslinking.

In addition to endowing DNs with the ability to withstand repeated loading, rapid self-healing of supramolecular bonds enabled hydrogel injection, which is crucial for minimally invasive delivery in biomedical applications. As demonstrated rheologically (Figure 1c), GH complexation enabled yielding and flow of GH single network hydrogels under application of high strain with subsequent rapid recovery. This unique quality was harnessed to enable injection, where upon injection into aqueous media (TEOA buffer; Figure 4d, Movie 6 in Supporting Information) GH DN and MethGH DN hydrogels exhibited near-instantaneous supramolecular re-assembly following injection, resulting in retention of the interpenetrating MeHA polymer which subsequently crosslinked to form a highly elastic DN (Figure 4e, Movie 7 in Supporting Information). Conversely, MeHA single networks rapidly diffused prior to crosslinking. Translation toward gelation in situ, such as for therapeutic in vivo injection, was evaluated through injection into various tissues post-mortem (Supporting Information, Figure S11). In all cases, including subcutaneous injection in rats, intramyocardial injection in ovine tissue, and filling of cartilaginous defects (Supporting Information, Movie 8), MeHA hydrogels were notably absent from the delivery location as a result of slow crosslinking kinetics; however, DN hydrogels were successfully retained at the injection locations. Moreover, upon mechanical examination of explanted samples, MethGH DNs maintained mechanical properties, including toughness, similar to those of in vitro formed controls. This combination of hydrogel injectability and mechanical toughness is a unique asset enabled by the tandem supramolecular and covalent crosslinking processes.

Supramolecular interactions, including ionic[10, 12, 13, 27], and hydrogen bonding[14, 28], and engineered binary associations[29], are essential in the development of tough materials. Yet, these methods have failed to deliver hydrogels that rapidly self-heal to enable sequential repetitive loading. We have harnessed the rapid association of supramolecular macrocycles to enable near-immediate internal self-healing of DN hydrogels, where concurrent and substantial amplification of the hydrogel toughness and elastic moduli were simultaneously achieved through tethering of the single networks to enable stress transfer during loading. In contrast to conventional DN formation, hydrogels were composed of orthogonal supramolecular and covalent bonding schemes, which enabled single step (one-pot) preparation without detriment to encapsulated cells and enabled maintenance of high cell viability in culture — features not observed in other DNs. Autonomy of the reactions, in combination with shear-yielding behavior of the supramolecular bonds, enabled injectability with in situ DN formation. Due to their unique load-bearing, injectable, and cytocompatible properties, hybrid supramolecular-covalent DNs are promising materials scaffolds for biomedical applications.

Experimental Section

Material synthesis

Hyaluronic acid (HA) with 25% (Me25HA) or 100% (Me100HA) of disaccharides modified by methacrylates was prepared by reaction with methacrylic anhydride. HA and Me25HA were both separately modified by Ad or aminated β-CD via anhydrous esterification and amidation, respectively, by modification of our previously reported protocols.[30] All final gel precursors were purified by extensive dialysis, recovered by lyophilization, and modifications determined by 1H NMR (Bruker, DMX 360 MHz). Further details of synthesis and hydrogel formation are are provided in the Supporting Information.

Mechanical testing

GH hydrogels were examined by oscillatory rheology (TA Instruments, AR2000) via frequency sweeps (0.01–100 Hz, 0.5% strain) and strain sweeps (1.0 Hz, 0.5–500% strain); covalent crosslinking was observed via time sweeps (1.0 Hz, 0.5% strain). Compressive properties were examined by dynamic mechanical analysis (TA Instruments, Q800, 0.5 N min−1), including compresive moduli, failure strain, failure stress, toughness, and hysteresis. Ultimate tensile properties were similarly explored (Instron, 5848, 10 N load cell, 5.0 mm sec−1). Detailed description of testing parameters and conditions is provided in the Supporting Information.

Cell viability

Hydrogels were prepared as described using supplemented Media 199 (Gibco). Live/dead staining (Molecular Probes) was assessed at 24 hours (day 0) and day 14, with viability reported as the percentage of cells with positive calcein staining. Representative images were obtained by confocal. To assess metabolic activity, Alamar blue (Fisher; 1:10 dilution with growth media, 4 hr incubation) was serially assessed by fluorescence quantification (Tecan, Infinite M200, λabs/em=530/590 nm), which was normalized to baseline for each sample. Detailed encapsulation and imaging protocols are provided in the Supporting Information.

Injection

Hydrogels were prepared using supplemented Media 199. Ex vivo injections were performed subcutaneously (rat, 300 μL ea.) and intramyocardially (ovine left ventricle, 200 μL ea.). Articular cartilage defects (bovine tibia, 5 mm) were filled by injection of hydrogels, contacted with the meniscus throughout crosslinking, and subsequently washed. All were incubated (37°C, 2 hrs) prior to excision and/or imaging. For subcutaneous injection, samples were collected (n ≥ 4, 4 mm diameter) and subjected to compressive analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with post hoc Tukey HSD to compare between groups unless otherwise stated. In all cases, significance was determined at P ≤ 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank B. Cosgrove and the Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders for technical assistance in tensile testing and procurement of cartilaginous tissue used, as well as A. Gaffey for procurement of animals used in post-mortem subcutaneous injection studies. This work was financially supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB008722, P30 AR050950) and the American Heart Association through a Predoctoral Fellowship (CBR) and Established Investigator Award (JAB).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- [1].Seliktar D, Science. 2012, 336, 1124; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tibbitt MW, Rodell CB, Burdick JA, Anseth KS, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015, 112, 14444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gong JP, Katsuyama Y, Kurokawa T, Osada Y, Adv. Mater 2003, 15, 1155. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Yasuda K, Gong JP, Katsuyama Y, Nakayama A, Tanabe Y, Kondo E, Ueno M, Osada Y, Biomaterials. 2005, 26, 4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Haque MA, Kurokawa T, Gong JP, Polymer. 2012, 53, 1805; [Google Scholar]; Costa AM, Mano JF, Eur. Polym. J 2015, 72, 344. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Brown HR, Macromolecules. 2007, 40, 3815. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gong JP, Soft Matter. 2010, 6, 2583. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Nonoyama T, Gong JP, Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine. 2015, 229, 853; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fung Y.-c., Biomechanics: mechanical properties of living tissues, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Webber RE, Creton C, Brown HR, Gong JP, Macromolecules. 2007, 40, 2919. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Diani J, Fayolle B, Gilormini P, Eur. Polym. J 2009, 45, 601. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sun TL, Kurokawa T, Kuroda S, Ihsan AB, Akasaki T, Sato K, Haque MA, Nakajima T, Gong JP, Nat. Mater 2013, 12, 932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Darnell MC, Sun J-Y, Mehta M, Johnson C, Arany PR, Suo Z, Mooney DJ, Biomaterials. 2013, 34, 8042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sun JY, Zhao XH, Illeperuma WRK, Chaudhuri O, Oh KH, Mooney DJ, Vlassak JJ, Suo ZG, Nature. 2012, 489, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Costa AM, Mano JF, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 15673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Guo M, Pitet LM, Wyss HM, Vos M, Dankers PY, Meijer E, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 6969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Truong VX, Ablett MP, Richardson SM, Hoyland JA, Dove AP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shin H, Olsen BD, Khademhosseini A, Biomaterials. 2012, 33, 3143; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fan C, Liao L, Zhang C, Liu L, Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2013, 1, 4251; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rennerfeldt DA, Renth AN, Talata Z, Gehrke SH, Detamore MS, Biomaterials. 2013, 34, 8241; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Brigham MD, Bick A, Lo E, Bendali A, Burdick JA, Khademhosseini A, Tissue Eng., Part A 2008, 15, 1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].DeKosky BJ, Dormer NH, Ingavle GC, Roatch CH, Lomakin J, Detamore MS, Gehrke SH, Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods. 2010, 16, 1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Appel EA, del Barrio J, Loh XJ, Scherman OA, Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 6195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rodell CB, Mealy JE, Burdick JA, Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Szejtli J, Chem. Rev 1998, 98, 1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Rekharsky MV, Inoue Y, Chem. Rev 1998, 98, 1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Highley CB, Prestwich GD, Burdick JA, Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 2016, 40, 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huang M, Furukawa H, Tanaka Y, Nakajima T, Osada Y, Gong JP, Macromolecules. 2007, 40, 6658. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shams Es-haghi S, Leonov A, Weiss R, Macromolecules. 2014, 47, 4769. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Nakajima T, Kurokawa T, Ahmed S, Wu W.-l., Gong JP, Soft Matter. 2013, 9, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Seiffert S, Sprakel J, Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Henderson KJ, Zhou TC, Otim KJ, Shull KR, Macromolecules. 2010, 43, 6193. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Monemian S, Korley LT, Macromolecules. 2015, 48, 7146. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Li C, Rowland MJ, Shao Y, Cao T, Chen C, Jia H, Zhou X, Yang Z, Scherman OA, Liu D, Adv. Mater 2015, 27, 3298; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tan M, Cui Y, Zhu A, Han H, Guo M, Jiang M, Polym. Chem 2015, 6, 7543; [Google Scholar]; Nakahata M, Takashima Y, Harada A, Macromol. Rapid Commun 2016, 37, 86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Rodell CB, Kaminski AL, Burdick JA, Biomacromolecules. 2013, 14, 4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.