Central Illustration

Key Words: acute coronary syndrome, complication, public health, STEMI

The current severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic has resulted in a unique global challenge for health care delivery, both in terms of the clinical sequelae of viral infection (coronavirus disease-2019 [COVID-19]) and the unintended consequences related to over-taxed health care systems. The virus enters cells by binding to the angiotensin-converting enzyme-2 receptor, which is abundantly present in the lung, heart, and vascular endothelial cells (1). This entry mechanism likely contributes to the clinical presentation of COVID-19 that includes pneumonia, hypoxemia, myocardial cell damage, cardiac dysfunction, and thrombosis, among others. The specific mechanism(s) of cardiac injury may include viral myocarditis, microthrombosis of small arterioles, cytokine-mediated plaque erosion or rupture, right-heart failure from acute respiratory distress syndrome, and oxygen supply-demand mismatch related to fever, tachycardia, and hypotension (1,2). Elevation in serum troponin reflects cardiomyocyte injury (direct or indirect), which occurs in 12% to 28% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients and predicts a 5- to 10-fold increased risk of in-hospital death (3). Thus, cardiac involvement in COVID-19 is both common and predictive of worse outcomes in affected patients.

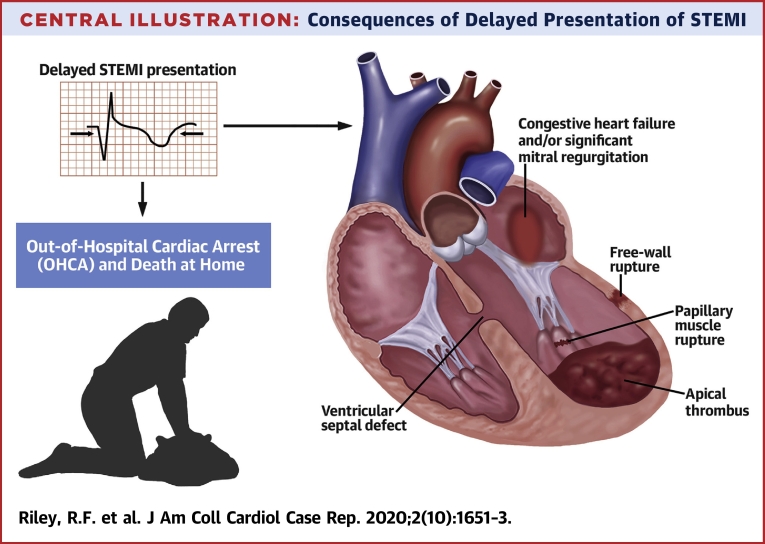

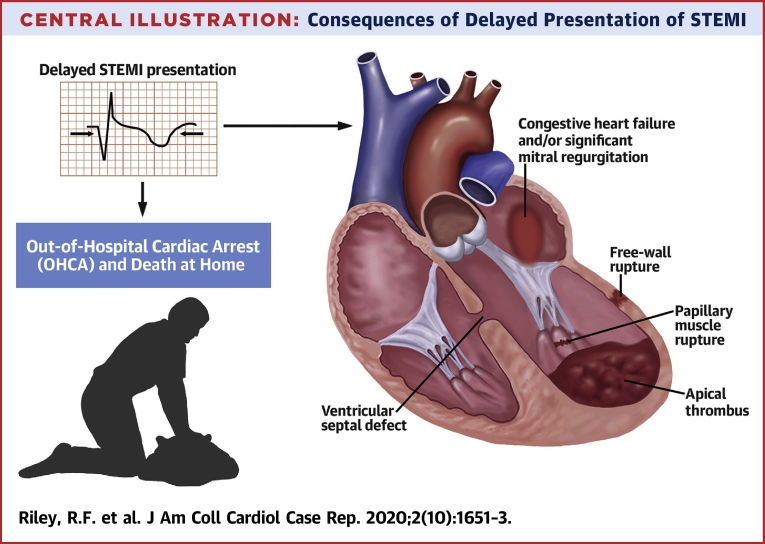

In an effort to preserve resources, including personal protective equipment, hospital beds, and respiratory ventilators, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended deferral of elective cardiac procedures including coronary angiography and revascularization using either percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (4). As hospitals filled with COVID-19 patients, fear grew among both care providers and the public regarding potential exposure to COVID-19, and many patients avoided going to hospitals or clinics (5). Additionally, hospitals adopted extremely limited visitation policies, often excluding family members of patients who were undergoing urgent or emergency procedures or who were in critical condition, which worsened public perception of health care facilities as COVID-19 “hotspots.” However, coincident with the rise in COVID-19 hospital admissions was an abrupt 30% to 40% decline in hospital visits for cardiovascular emergencies including STEMI, stroke, heart failure, and aortic dissection, in both Europe and the United States, despite the fact that patients with cardiovascular disease were at higher risk of complications related to COVID-19, including thrombotic events (6,7). At a time when pandemic-related environmental and psychosocial stressors might have prompted an increased incidence of STEMI, this paradoxical decrease in STEMI presentation was associated with significant increases in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and of death at home, compared to a similar time period in 2019, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (8,9). Furthermore, door-to-balloon and transfer in (door-to-door-to-balloon) STEMI times for primary PCI were also prolonged due to extensive safety precautions required to protect physicians and hospital staff and limit infectious exposure (10,11). Concern over COVID-19 cardiac involvement “masquerading” as STEMI with ST-segment elevation in the absence of obstructive coronary disease in up to 50% of cases caused additional ambiguity in diagnosis for patients presenting with STEMI and created impediments to timely care delivery (12, 13, 14, 15). Even for those STEMI patients who presented for medical attention, the lack of accurate diagnostic COVID-19 testing coupled with concern by clinicians for infectious exposure prompted calls for thrombolytic therapy (“no touch approach”) even in PCI-capable centers, despite established data that primary PCI reduced mortality associated with STEMI compared to thrombolytic therapy and current societal guidelines supporting primary PCI as the standard of care for STEMI (10,16). Thus, both the delayed and the diminished presentations of STEMI have been associated with an increased incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and death at home, many of which were likely STEMIs occurring at home. Additionally, there appears to have been an increase in mechanical complications of late-presenting STEMI (ventricular septal defect, free wall rupture, papillary muscle rupture, left ventricular thrombus, congestive heart failure, and cardiogenic shock), as shown in the Central Illustration (7,12, 13).

Central Illustration.

Consequences of Delayed Presentation of STEMI

STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

This issue of JACC: Case Reports focuses on the impact of delayed presentation of STEMI during the COVID era and the ensuing mechanical complications. Alsidawi et al. (17) present cases of delayed STEMI presentation due to patient reluctance to seek medical attention that manifested as subacute coronary occlusions and concurrent ventricular septal defects. Albierto and Seresini et al. (18) present a case of delayed anterolateral STEMI resulting in a ventricular free-wall rupture that required emergent surgical repair. Moroni et al. (19) present a series of patients with delayed presentation for STEMI associated with cardiogenic shock on presentation. Kunkel and Anwaruddin (20) describe a patient with delayed presentation of inferior STEMI that resulted in papillary muscle rupture and severe mitral regurgitation which required emergency surgical intervention. Yousefzai and Bhimaraj (21) present a patient who was misdiagnosed with presumed COVID-19 infection but who actually had an acute coronary syndrome. Unfortunately, the delay in diagnosis had significant consequences.

Thus, COVID-19 has directly and indirectly impacted the care of patients with cardiovascular emergencies. Ambiguity in diagnosis, delay or lack of myocardial reperfusion, and regression from primary PCI as the treatment of choice for STEMI to thrombolysis despite current clinical practice guideline recommendations have taken STEMI care backward in time by decades (10). Therefore, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions recently launched “The Seconds Still Count: Cardiovascular Disease Doesn’t Stop for COVID-19” campaign (22). We need strong support from current professional societal guidelines and a concerted public education campaign to bring the care of STEMI patients “Back to the Future.”

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the JACC: Case Reportsauthor instructions page.

References

- 1.Atri D., Siddiqi H.K., Lang J., Nauffal V., Morrow D., Bohula E. COVID-19 for the cardiologist: a current review of the virology, clinical epidemiology, cardiac and other clinical manifestations and potential therapeutic strategies. J Am Coll Cardiol Basic Trans Science. 2020;5:518–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried J.A., Ramasubbu K., Bhatt R. The variety of cardiovascular presentations of COVID-19. Circulation. 2020;141:1930–1936. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M. Cardiovascular Implications of Fatal Outcomes of Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Surgeons Joint Statement: Roadmap for Resuming Elective Surgery after COVID-19 Pandemic. https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/roadmap-elective-surgery Available at:

- 5.De Filippo I., D’Ascenzo F., Angelini F. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during COVID-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. N Eng J Med. 2020;383:88–89. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzler B., Siostrzonek P., Binder R.K. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852–1853. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia S., Albaghdadi M.S., Meraj P.M. Reduction in ST-segment elevation cardiac catheterization laboratory activations in the United States during COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2871–2872. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldi E., Sechi G.M., Mare C. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. N Eng J Med. 2020;383:496–498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong L.E., Hawkins J.E., Langness S., Murrell K.L., Iris P., Sammann A. Where are all the patients? Addressing covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care. N Engl J Med. 2020 [E-pub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahmud E., Dauerman H.L., Welt F.G.P. Management of acute myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Apr 21 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.039. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Welt F.G.P., Shah P.B., Aronow H.D. Catheterization laboratory considerations during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: from ACC’s Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2372–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon M.D., McNulty E.J., Rana J.S. The covid-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020 May 19 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt A.S., Moscone A., McElrath E.E. Fewer hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:280–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bangalore S., Sharma A., Slotwiner A. ST-segment elevation in patients with covid-19-A case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2478–2480. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stefanini G.G., Montorfano M., Trabattoni D. ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients with COVID-19: clinical and angiographic outcomes. Circulation. 2020;141:2113–2116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.047525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bainey K.R., Bates E.R., Armstrong P.W. ST-segment–elevation myocardial infarction care and COVID-19. The value proposition of fibrinolytic therapy and the pharmacoinvasive strategy. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:e006834. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.120.006834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alsidawi S., Campbell A., Tamene A., Garcia S. Ventricular septal rupture complicating delayed acute myocardial infarction presentation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1595–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Albiero R., Seresini G. Subacute left ventricular free wall rupture after delayed STEMI presentation during COVID-19 pandemic: a case report. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1603–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moroni F., Gramegna M., Ajello S., Baldetti L., Vilca L.M. Collateral damage: medical care avoidance behavior among patients with acute coronary syndrome during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1620–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunkel K.J., Anwaruddin S. Papillary muscle rupture due to delayed STEMI presentation in a patient self-isolating for presumed COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1633–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yousefzai R., Bhimaraj A. Misdiagnosis in the COVID era: when zebras are everywhere, don’t forget the horses. J Am Coll Cardiol Case Rep. 2020;2:1614–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions Cardiovascular Disease Doesn't Stop for COVID-19. SCAI, Washington, DC. http://secondscount.org/heart-resources/covid-19-facts#.XwTN9ihKg2w Available at: