Abstract

Background

In the United States, since 2016, at least 28 of 50 state legislatures have passed laws regarding mandatory prescribing limits for opioid medications. One of the earliest state laws (which was passed in Rhode Island in 2016) restricted the maximum morphine milligram equivalents provided in the first postoperative prescription for patients defined as opioid-naïve to 30 morphine milligram equivalents per day, 150 total morphine milligram equivalents, or 20 total doses. While such regulations are increasingly common in the United States, their effects on opioid use after total joint arthroplasty are unclear.

Questions/purposes

(1) Are legislative limitations to opioid prescriptions in Rhode Island associated with decreased opioid use in the immediate (first outpatient prescription postoperatively), 30-day, and 90-day periods after THA and TKA? (2) Is this law associated with similar changes in postoperative opioid use among patients who are opioid-naïve and those who are opioid-tolerant preoperatively?

Methods

Patients undergoing primary THA or TKA between January 1, 2016 and June 28, 2016 (before the law was passed on June 28, 2016) were retrospectively compared with patients undergoing surgery between June 1, 2017 and December 31, 2017 (after the law’s implementation on April 17, 2017). The lapse between the pre-law and post-law periods was designed to avoid confounding from potential voluntary practice changes by physicians after the law was passed but before its mandatory implementation. Demographic and surgical details were extracted from a large multi-specialty orthopaedic group’s surgical billing database using Current Procedural Terminology codes 27130 and 27447. Any patients undergoing revision procedures, same-day bilateral arthroplasties, or a second primary THA or TKA in the 3-month followup period were excluded. Secondary data were confirmed by reviewing individual electronic medical records in the associated hospital system which included three major hospital sites. We evaluated 1125 patients. In accordance with the state’s department of health guidelines, patients were defined as opioid-tolerant if they had filled any prescription for an opioid medication in the 30-day preoperative period. Data on age, gender, and the proportion of patients who were defined as opioid tolerant preoperatively were collected and found to be no different between the pre-law and post-law groups. The state’s prescription drug monitoring program database was used to collect data on prescriptions for all controlled substances filled between 30 days preoperatively and 90 days postoperatively. The primary outcomes were the mean morphine milligram equivalents of the initial outpatient postoperative opioid prescription after discharge and the mean cumulative morphine milligram equivalents at the 30- and 90-day postoperative intervals. Secondary analyses included subgroup analyses by procedure and by preoperative opioid tolerance.

Results

After the law was implemented, the first opioid prescriptions were smaller for patients who were opioid-naïve (mean 156 ± 106 morphine milligram equivalents after the law’s passage versus 451 ± 296 before, mean difference 294 morphine milligram equivalents; p < 0.001) and those who were opioid-tolerant (263 ± 265 morphine milligram equivalents after the law’s passage versus 534 ± 427 before, mean difference 271 morphine milligram equivalents; p < 0.001); however, for cumulative prescriptions in the first 30 days postoperatively, this was only true among patients who were previously opioid-naïve (501 ± 416 morphine milligram equivalents after the law’s passage versus 796 ± 597 before, mean difference 295 morphine milligram equivalents; p < 0.001). Those who were opioid-tolerant did not have a decrease in the cumulative number of 30-day morphine milligram equivalents (1288 ± 1632 morphine milligram equivalents after the law’s passage versus 1398 ± 1274 before, mean difference 110 morphine milligram equivalents; p = 0.066).

Conclusions

The prescription-limiting law was associated with a decline in cumulative opioid prescriptions at 30 days postoperatively filled by patients who were opioid-naïve before total joint arthroplasty. This may substantially impact public health, and these policies should be considered an important tool for healthcare providers, communities, and policymakers who wish to combat the current opioid epidemic. However, given the lack of a discernible effect on cumulative opioids filled from 30 to 90 days postoperatively, further investigations are needed to evaluate more effective policies to prevent prolonged opioid use after total joint arthroplasty, particularly in patients who are opioid-tolerant preoperatively.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Introduction

Opioid misuse has reached epidemic proportions in the United States, with 47,600 opioid-related deaths in 2017 alone [8]. Although an increase in the availability and use of illicit substances including heroin and synthetic fentanyl have contributed greatly to this crisis, 35% of opioid-related overdose deaths continue to involve prescription opioid medications [26]. The dose and duration of opioid treatment provided by medical providers has been associated with an increased risk of opioid abuse and chronic use by patients [6, 27]. Improved opioid stewardship by orthopaedic surgeons is of paramount importance for improving public health and individual patient outcomes after total joint arthroplasty [20].

The opioid prescribing rate peaked from 2010 to 2012 and has been gradually declining since, which may reflect increasing caution among healthcare providers [26]. However, opioid use after orthopaedic surgery continues to be unacceptably high [1, 5]. Public health interventions including widespread use of prescription drug monitoring programs, have shown limited evidence of efficacy [21]. In June 2016, to combat the opioid crisis, the state of Rhode Island passed the Rhode Island Uniform Controlled Substances Act [2]. Aspects of this law, which places strict limits on prescribers and pharmacies, were implemented in 2017. These regulations mandate that opioid prescriptions for individuals defined as opioid-naïve may not exceed 30 morphine milligram equivalents per day, 150 total morphine milligram equivalents, or 20 total doses [24]. This law has been associated with decreased opioid use in the early period after lumbar spine surgery [23]; however, to our knowledge, the effect of such a law on patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty has never been evaluated. Although there is some overlap, patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery and those electing to undergo total joint arthroplasty are distinct clinical populations with differing etiologies of pain, medical comorbidities, and levels of resiliency.

We therefore asked: (1) Are legislative limitations to opioid prescriptions in Rhode Island associated with decreased opioid use in the immediate (first outpatient prescription postoperatively), 30-day, and 90-day periods after THA and TKA? (2) Is this law associated with similar changes in postoperative opioid use among patients who are opioid-naïve and those who are opioid-tolerant preoperatively?

Patients and Methods

Approval was obtained from the institutional review boards of our hospital system and state Department of Health. We retrospectively reviewed the records of all patients undergoing primary THA or TKA in the designated pre-law and post-law periods (pre-law: January 1, 2016 to June 28, 2016; post-law: June 1, 2017 to December 31, 2017). A substantial time lapse between the pre-law and post-law periods was necessary to accurately define the cohorts. Although the law was passed on June 28, 2016, it was not officially implemented until April 17, 2017. Because some physicians may have adjusted their prescribing practices after passage of the law but before its implementation in anticipation of the required changes, this time period was excluded. The study periods were defined so that all patients in the pre-law cohort underwent their procedures before the law was passed, and all patients in the post-law cohort underwent their procedures after the mandatory implementation date. All patients undergoing primary TKA or THA with a large multi-specialty orthopaedic group in Rhode Island during the study period were eligible for study inclusion. Those undergoing revision procedures, more than one arthroplasty procedure simultaneously, or a second arthroplasty during the 30-day preoperative or 90-day follow-up periods were excluded. Procedures were identified through internal billing records. Current Procedural Terminology codes 27130 and 27447 were used to initially identify procedures. We reviewed the records of all hospitals in the system to confirm the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment. The specific surgical technique, perioperative pain control strategies, and preoperative and postoperative clinical pathways were chosen at the discretion of the treating surgeon.

A total of 1407 patients (625 with THA and 782 with TKA) undergoing surgery during the specified time periods were identified. Of these, 1125 patients (489 with THA and 636 with TKA) met the study’s inclusion criteria and had complete prescription data available for analysis. Five-hundred fifty-five patients underwent surgery during the pre-law period and 570 underwent surgery during the post-law period.

Patients in both groups were not different regarding age, gender, and preoperative opioid tolerance (Table 1). The post-law group had a slightly higher proportion of patients with preoperative benzodiazepine exposure (10.9%) than the pre-law group did (7.2%; p = 0.032).

Table 1.

Patient demographics

For each patient, Rhode Island’s prescription drug monitoring program database was used to review all prescriptions for controlled substances filled between 30 and 90 days postoperatively. All oral formulations of codeine, hydrocodone, morphine, oxycodone, and tramadol were collected and converted to their equivalent morphine milligram equivalents. Additionally, preoperative benzodiazepine use was recorded and included prescriptions of alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, quazepam, temazepam, and triazolam. In accordance with the Rhode Island Department of Health regulations [24], opioid tolerance was defined as any opioid prescription filled in the 30-day preoperative period. Conversely, patients were considered opioid-naïve if they had not filled any opioid prescriptions within 30 days of surgery. The number of opioid prescriptions and the cumulative morphine milligram equivalents for all prescriptions filled in the first 90 days postoperatively were recorded. Prescription data beyond 90 days were not evaluated to prevent bias from medications filled for unrelated indications.

Statistical testing was performed on continuous variables using a t-test and Mann-Whitney U test, as required based on normality testing. Before data were collected and analyzed, statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. A post-hoc power analysis was performed for the primary outcome (cumulative 30-day postoperative morphine milligram equivalents). Using an alpha of 0.05 and beta of 0.80, sample size estimates included 136 patients per cohort, or 272 total patients. Stata 15.0 computational software (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) was used to conduct all statistical tests. Microsoft Excel version 16.11.1 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) was used to collect and visualize data.

Results

Overall Reductions in Opioid Use After Implementation of the Prescription-limiting Law

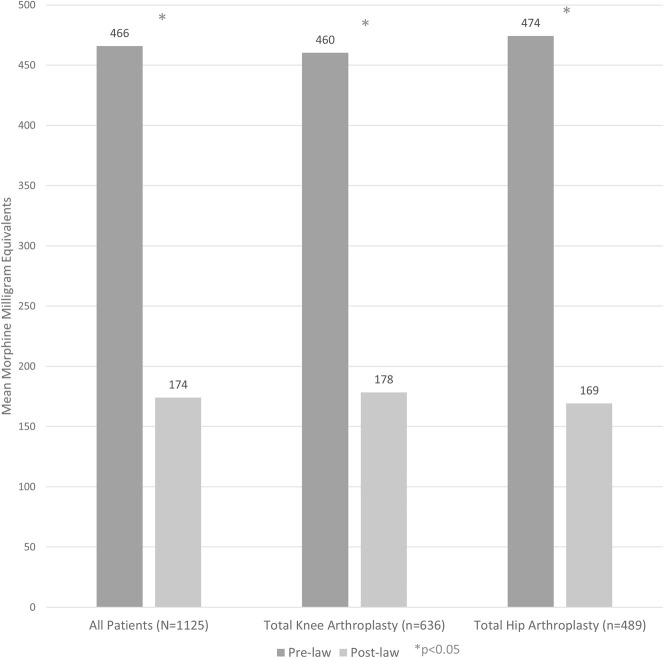

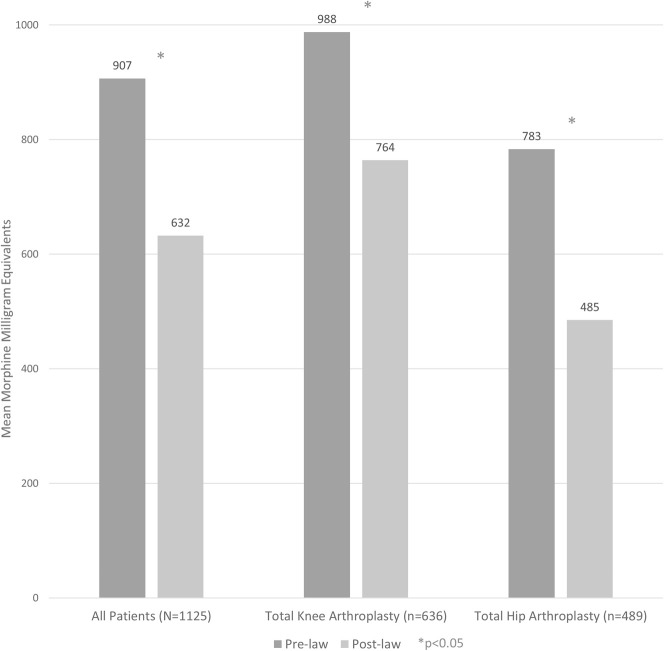

Among all patients analyzed (n = 1125), those who underwent surgery after the law was implemented received fewer morphine milligram equivalents at the time of hospital discharge than did those who underwent surgery before the law was passed (174 ± 150 morphine milligram equivalents versus 466 ± 325 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 292 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 262 to 321 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) (Table 2) (Fig. 1). The same was also true when examining cumulative postoperative opioid prescriptions 30 days postoperatively (632 ± 819 morphine milligram equivalents versus 907 ± 800 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 275 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 180 to 369 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) but not 30 to 90 days postoperatively (270 ± 46 morphine milligram equivalents versus 279 ± 34 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 9 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, -104 to 123 morphine milligram equivalents]; p = 0.192) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Pre-law versus post-law postoperative opioid prescriptions, stratified by procedure performed

Fig. 1.

After implementation of the prescription-limiting law, patients who underwent THA and TKA received fewer morphine milligram equivalents in their first postoperative opioid prescription than did those undergoing surgery before the law was passed.

Fig. 2.

The mean cumulative morphine milligram equivalents filled in the first 30 days after surgery was lower in the post-law cohort than in the pre-law group, regardless of procedure (TKA or THA).

The results were no different after stratification by procedure (TKA versus THA). Specifically, among patients undergoing TKA (n = 636), post-law patients received fewer initial morphine milligram equivalents than pre-law patients did (178 ± 158 morphine milligram equivalents versus 460 ± 305 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 282 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 243 to 320 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) and cumulative 30-day morphine milligram equivalents (764 ± 904 morphine milligram equivalents versus 988 ± 775 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 224 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 93 to 355 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) but not cumulative 30- to 90-day morphine milligram equivalents (342 ± 1340 morphine milligram equivalents versus 304 ± 729 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 37 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, -128.56 to 202.99 morphine milligram equivalents]; p = 0.391).

Likewise, among patients undergoing THA (n = 489), post-law patients received fewer initial morphine milligram equivalents than pre-law patients did (169 ± 140 morphine milligram equivalents versus 474 ± 352 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 305 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 259 to 351 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) and cumulative 30-day morphine milligram equivalents (485 ± 684 morphine milligram equivalents versus 783 ± 825 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 298 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 164 to 432 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001), but by 30 to 90 days after surgery, post-law patients were no different than their pre-law counterparts (189 ± 770 morphine milligram equivalents versus 240 ± 922 morphine milligram equivalents, mean difference 51 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, -99 to 201 morphine milligram equivalents]; p = 0.854). A small post-law increase in the absolute number of opioid prescriptions filled in the first 30 days postoperatively was observed among all patients (2.2 ± 1.3 prescriptions versus 1.9 ± 1.3 prescriptions, mean difference 0.3 prescriptions [95% CI, 0.1 to 0.4 prescriptions]; p < 0.001), among those undergoing TKA (2.6 ± 1.4 prescriptions versus 2.2 ± 1.4 prescriptions, mean difference 0.4 prescriptions [95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6 prescriptions]; p < 0.001), and among those undergoing THA (1.8 ± 1.1 prescriptions versus 1.5 ± 1.1 prescriptions, mean difference 0.3 prescriptions [95% CI, 0.1 to 0.5 prescriptions]; p = 0.007) (Table 2).

Differences Between Patients Based on Prior Opioid Exposure

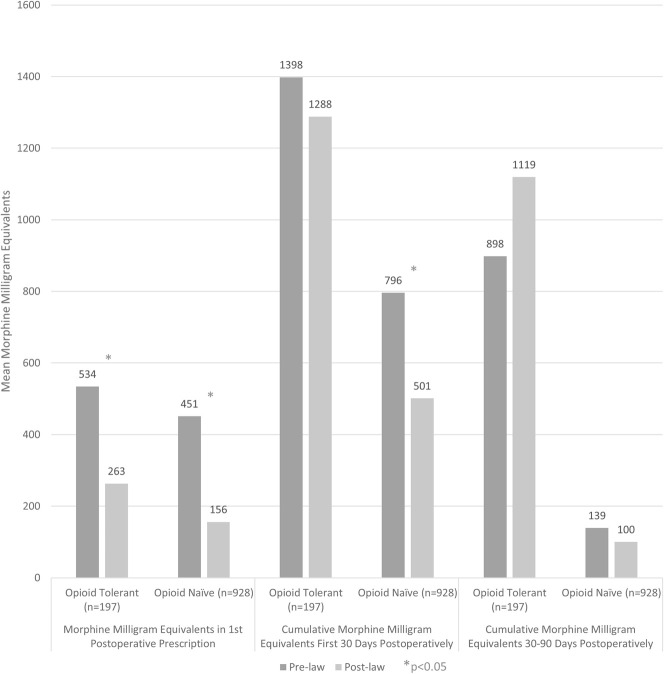

After the law was implemented, the first opioid prescriptions were smaller for patients who were opioid-naïve (156 ± 106 morphine milligram equivalents after the law was passed versus 451 ± 296 morphine milligram equivalents before, mean difference 294 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 266 to 323 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) and for those who were opioid-tolerant (263 ± 265 morphine milligram equivalents after the law’s passage versus 534 ± 427 morphine milligram equivalents before, mean difference 271 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 179 to 371 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001) (Table 3) (Fig. 3). However, for cumulative prescriptions 30 days postoperatively, this was only found among patients who were previously opioid-naïve (501 ± 416 morphine milligram equivalents after passage of the law versus 796 ± 597 before, mean difference 294 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, 229 to 361 morphine milligram equivalents]; p < 0.001). Those who were opioid-tolerant, in contrast, did not have a post-law decrease in morphine milligram equivalents prescribed during this time period (1288 ± 1632 morphine milligram equivalents after the law was passed versus 1398 ± 1274 morphine milligram equivalents before, mean difference 110 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, -300 to 520 morphine milligram equivalents]; p = 0.066). By 90 days after surgery, no post-law reduction in cumulative morphine milligram equivalents was observed, either in patients defined as opioid-naïve (100 ± 354 morphine milligram equivalents after passage of the law versus 139 ± 424 morphine milligram equivalents before, mean difference 40 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, -11 to 90 morphine milligram equivalents]; p = 0.176) or those defined as opioid-tolerant (1119 ± 2440 morphine milligram equivalents after the law was passed versus 898 ± 1524 morphine milligram equivalents before, mean difference -221 morphine milligram equivalents [95% CI, -788 to 347 morphine milligram equivalents]; p = 0.967).

Table 3.

Pre-law versus post-law postoperative opioid prescriptions, stratified by preoperative opioid status

Fig. 3.

Although the law was associated with smaller initial opioid prescriptions in all patients after surgery, only opioid-naïve patients had a decrease in cumulative morphine milligram equivalents at 30 days. There was no association between this opioid-limiting law and changes in cumulative morphine milligram equivalents prescribed more than 30 days after surgery, regardless of preoperative opioid exposure.

Discussion

Over one million total joint arthroplasties are performed yearly in the United States, with continued growth expected for the foreseeable future [11, 17]. While routinely prescribed to control pain after THA and TKA, prescription opioid medications have been associated with poorer postoperative clinical outcomes and contribute to an ongoing opioid epidemic in the United States [3, 7, 12, 18, 19, 25, 28]. Since 2016, to address the opioid crisis, at least 28 states have passed regulations on mandatory opioid prescription dose limits. However, the impact of this law on early and late prescribing practices after total joint arthroplasty was previously unknown. This investigation noted a reduction in initial and 30-day postoperative morphine milligram equivalents filled by patients undergoing THA and TKA after implementation of the Rhode Island Uniform Controlled Substances Act [2]. In addition, despite specific legislative exemptions for patients defined as opioid-tolerant, those exposed to opioids preoperatively nevertheless experienced a similar decline in initial morphine milligram equivalents filled after the regulations were implemented.

There are several potential limitations to this analysis. This law was passed during a period of national media attention and increasing awareness among providers, patients, legislators, and society about the potential negative effects of opioids. There is evidence of a preexisting downward trend in prescription opioid use after a peak in 2010 to 2012 [26]. Furthermore, a substantial period (11 months) passed between the pre-law and post-law study periods. This was inherent to the study design and secondary to a 9.5-month delay between the passage and implementation of the law as well as a 1.5-month post-implementation delay in data collection designed to allow time for prescribers and pharmacies to adjust practices accordingly. Nevertheless, other simultaneous interventions including education programs and hospital and practice-based guidelines may have been implemented during this time and may serve as confounding variables. Because this was a retrospective study, we cannot fully control for such confounding variables and are only able to evaluate for association, not causation. Thus, the observed reduction in postoperative opioid use could have been caused by the law in question, national trends, confounding variables, or most likely a combination of these factors.

During our secondary analysis after stratification by preoperative opioid exposure, we defined patients as opioid-tolerant if they had filled any opioid prescription in the 30-day preoperative period. Patients who had not were considered opioid-naïve. Although “opioid-exposed” may be a more accurate term for this group, “opioid-tolerant” was nonetheless used to reflect the regulatory language, similar to prior research in the field [24]. A substantial amount of variation in preoperative opioid exposure in terms of both dosage and duration existed at baseline among patients. Although strict dichotomization results in a loss of granularity and nuance in a clearly complex field, it also allows us to more clearly answer our primary research question regarding any association between the law and opioid use among opioid-naïve and opioid-tolerant populations.

The Rhode Island prescription drug monitoring program records all information on controlled substances from outpatient pharmacies in Rhode Island and the surrounding states; however, it does not include prescription information from inpatient stays or rehabilitation units and nursing homes. Our inability to truly understand opioid prescription patterns during inpatient stays prevents us from controlling for potential confounders, including variable early inpatient pain control in the early postoperative period. Furthermore, opioid use among those who undergo rehabilitation and/or nursing home care after total joint arthroplasty may differ from the opioid use of patients discharged home. Additionally, although granular information of prescriptions filled at pharmacies is given, the proportion of pills patents truly consume is unknown. A knowledge of true consumption patterns in addition to pharmacy dispensing records may help further elucidate individual patient opioid-related risk as well as the risk of diversion of unused pills for non-medical use.

This study was performed in Rhode Island, a unique northeastern state that is geographically small, densely populated, and moderately diverse. Although Rhode Island has no large cities, it also has no true rural areas. Although this state was an excellent study location in terms of data capture, location may have affected the generalizability of our findings. Specifically, large metropolitan areas and rural areas may be affected in different ways by this law. Furthermore, the specifics of opioid-limiting laws may vary by state in material ways. Although a number of states have passed similar laws, no two laws are identical. Even small variations in legislation, implementation, and/or funding may have profound impacts on the outcomes after such regulations are passed. For example, in Rhode Island, prescribers can prescribe opioid medications electronically, making secondary refills of prescriptions convenient for patients and providers. In locations where only paper opioid prescriptions are accepted, prescribers may be hesitant to prescribe small initial doses in anticipation of required refills. This may be especially problematic in rural or dense urban areas, where access to healthcare services can be difficult.

Finally, approximately 20% of initially identified patients were either excluded after meeting predefined exclusion criteria or had incomplete data available. A number of patients could not be located in the prescription drug monitoring database. Patients with hyphenated names and those who had changed names were particularly difficult to locate. Patients who have never filled a prescription for a controlled substance of any kind may not have been entered in the database. Furthermore, although database entry is mandatory, the database relies on accurate reporting by dispensing pharmacies. Our results may be at risk of selection bias if the populations missing from the prescription drug monitoring database differed systematically between the pre-law and post-law study periods.

Patients undergoing surgery after implementation of the law received fewer total morphine milligram equivalents in the first prescription and within the first 30 postoperative days than did patients undergoing surgery before the law was passed. However, after the first 30 postoperative days, no difference in the total morphine milligram equivalents filled was detected between cohorts. To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty before and after these regulations. A prior evaluation of the effect of this law on patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery by our study group similarly noted a decrease in initial and 30-day but not 30- to 90-day opioid use after lumbar discectomy, isolated lumbar decompression, and posterior lumbar fusion [23]. The current findings complement and expand on this prior work, providing evidence of decreased early postoperative opioid use in patients undergoing THA and TKA. However, as previously noted in a population of patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery, we found no evidence of any post-law changes in opioid use patterns more than 30 days after total joint arthroplasty. These findings suggest that this law is unlikely to be effective in decreasing prolonged and/or chronic opioid use after orthopaedic surgery. Nonetheless, the substantial decrease in cumulative opioids filled in the 30-day postoperative period observed after implementation of this law in both patient populations may result in a decreased risk of opioid diversion.

A large amount of unused medication after orthopaedic surgery has been cited as a major risk for both abuse and diversion of opioids for non-medical use; a recent single-institution review of 1199 orthopaedic procedures by Sabatino et al. [25] noted that more than 43,000 opioid pills were prescribed but unused during a 1-year study period. Furthermore, only 41% of patients reported appropriate disposal of their unused opioids. A recently published trial by Hannon et al. [12] randomized 161 patients who underwent total joint arthroplasty to receive either 30 or 90 pills of 5 mg immediate-release oxycodone. At 30 days after surgery, patients who were prescribed 30 pills had a median of 15 unused pills, and those prescribed 90 pills had a median of 73 unused pills. The authors concluded that initially prescribing fewer oxycodone pills was associated with a reduction in unused opioid pills without associated changes in pain scores or patient-reported outcomes. Thus, a policy associated with substantially fewer opioid prescriptions in the early period after total joint arthroplasty has potential positive public health implications in terms of fewer leftover pills available for diversion. Future research should evaluate the association between this law and changes in postoperative pain control, patient satisfaction, health-related quality of life measures, emergency department use, unplanned readmissions, and complications. Furthermore, the potential for any unintended consequences such as increased illicit use of opioids among patients with poor postoperative pain control should be investigated.

After implementation of the law, patients defined as opioid-naïve and those considered opioid-tolerant received fewer morphine milligram equivalents in the first prescription; however, only those who were opioid-naïve received fewer cumulative 30-day postoperative opioids in this period. Preoperative opioid exposure is a well-known risk factor for prolonged opioid use after total joint arthroplasty [4, 9, 13–15, 20, 22]. Thus, the lack of an association between the law and cumulative 30-day opioids after total joint arthroplasty among those defined as opioid-tolerant was unsurprising. In contrast to those defined as opioid-naïve, those filling any opioid prescription within 30 days preoperatively were specifically exempted from the new law. Despite this clear exception, those who were opioid-tolerant nevertheless received fewer morphine milligram equivalents in the initial postoperative prescription after the law was implemented. These findings may reflect an increasing use of standardized protocols and clinical pathways for improving quality in joint arthroplasty centers [10, 16, 29, 30]. Specifically, while the law in question mandates opioid-prescription limits only for those defined as opioid-naïve, providers may nevertheless be adjusting their initial prescribing protocols generally, independent of preoperative opioid exposure. Regardless, by 30 days postoperatively, patients who were opioid-tolerant appeared to rebound, requiring similar cumulative 30-day opioid doses as their pre-law counterparts despite starting with smaller initial prescriptions.

The results of this study provide early evidence that a targeted law limiting postoperative prescriptions may be associated with decreased early opioid prescriptions after THA and TKA. Early postoperative reductions in opioids filled may diminish the pool of unused medication available for diversion and thus positively impact public health. Nevertheless, no association between this law and opioid prescriptions more than 30 days after surgery was seen in any patients. Additionally, no association with decreased cumulative opioids filled was seen beyond the first outpatient prescription among patients exposed to opioids preoperatively. Therefore, future research should investigate more-effective policies to prevent prolonged opioid use after total joint arthroplasty, particularly in patients who were opioid-tolerant before surgery.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Lifespan Corporation, and the Rhode Island Department of Health for providing institutional support for this important project.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that neither he, nor any member of his or her immediate family, has funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

One or more authors has received funding outside the submitted work. EK reports receiving royalties from Integra Medical. AHD reports receiving grants and personal fees from Orthofix, personal fees from Stryker, personal fees from EOS, personal fees from Spineart, and royalties from Springer.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his institution approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

This work was performed at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

References

- 1.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Opioid use, misuse, and abuse in orthopaedic practice. Available at: https://www.aaos.org/uploadedfiles/preproduction/about/opinion_statements/advistmt/1045 opioid use, misuse, and abuse in practice.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2018.

- 2.Archambault S, Lombardi F, Prata E, McCaffrey M, Metts H. Chapter 21-28 Uniform Controlled Substances Act. Available at: http://webserver.rilin.state.ri.us/Statutes/TITLE21/21-28/INDEX.HTM. Accessed March 29, 2019.

- 3.Bedard NA, DeMik DE, Dowdle SB, Owens JM, Liu SS, Callaghan JJ. Preoperative opioid use and its association with early revision of total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3520-3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedard NA, Pugely AJ, Westermann RW, Duchman KR, Glass NA, Callaghan JJ. Opioid use after total knee arthroplasty: trends and risk factors for prolonged use. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2390-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bicket M, White E, Wu C, Pronovost P, Yaster M, Alexander G. (232) Prescription opioid oversupply following orthopedic surgery: a prospective cohort study. J Pain. 2017;18:S34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, Yorkgitis B, Bicket M, Homer M, Fox KP, Knecht DB, McMahill-Walraven CN, Palmer N, Kohane I. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cancienne JM, Patel KJ, Browne JA, Werner BC. Narcotic use and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: drug overdose death data. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed September 23, 2018.

- 9.Cryar KA, Hereford T, Edwards PK, Siegel E, Barnes CL, Mears SC. Preoperative smoking and narcotic, benzodiazepine, and tramadol use are risk factors for narcotic use after hip and knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2774-2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis TA, Hammoud H, Dela Merced P, Nooli NP, Ghoddoussi F, Kong J, Krishnan SH. Multimodal clinical pathway with adductor canal block decreases hospital length of stay, improves pain control, and reduces opioid consumption in total knee arthroplasty patients: a retrospective review. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:2440-2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fingar KR, Stocks C, Weiss AJ, Steiner CA. Most frequent operating room procedures performed in U.S. hospitals, 2003-2012. Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb186-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed April 6, 2019. [PubMed]

- 12.Hannon CP, Calkins TE, Li J, Culvern C, Darrith B, Nam D, Gerlinger TL, Buvanendran A, Della Valle CJ. The James A. Rand Young Investigator’s Award: large opioid prescriptions are unnecessary after total joint arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.01.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hereford TE, Cryar KA, Edwards PK, Siegel ER, Barnes CL, Mears SC. Patients with hip or knee arthritis underreport narcotic usage. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3113-3117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez NM, Parry JA, Mabry TM, Taunton MJ. Patients at risk: preoperative opioid use affects opioid prescribing, refills, and outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:S142-S146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hernandez NM, Parry JA, Taunton MJ. Patients at Risk: Large opioid prescriptions after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2395-2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holte AJ, Carender CN, Noiseux NO, Otero JE, Brown TS. Restrictive opioid prescribing protocols following total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty are safe and effective. J Arthroplasty. 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2019.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurtz S. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2007;89:780-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manalo JP, Castillo T, Hennessy D, Peng Y, Schurko B, Kwon Y-M. Preoperative opioid medication use negatively affect health related quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2018;25:946-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Namba RS, Inacio MCS, Pratt NL, Graves SE, Roughead EE, Paxton EW. Persistent opioid use following total knee arthroplasty: a signal for close surveillance. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:331-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namba RS, Paxton EW, Inacio MC. Opioid prescribers to total joint arthroplasty patients before and after surgery: the majority are not orthopedists. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3118-3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med . 2011;12:747-754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Politzer CS, Kildow BJ, Goltz DE, Green CL, Bolognesi MP, Seyler TM. Trends in opioid utilization before and after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:S147-S153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reid DB, Shah KN, Ruddell JH, Shapiro B, Akelman E, Robertson AP, Palumbo MA, Daniels AH. Effect of narcotic prescription limiting legislation on opioid utilization following lumbar spine surgery. Spine J . 2018;19:717-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Island Department of Health Rhode. 216-RICR-20-20-4. Available at: https://risos-apa-production-public.s3.amazonaws.com/DOH/REG_9702_20180806190700.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2018.

- 25.Sabatino MJ, Kunkel ST, Ramkumar DB, Keeney BJ, Jevsevar DS. Excess opioid medication and variation in prescribing patterns following common orthopaedic procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:180-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2019;67:1419-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah A, Hayes CJ, Martin BC. Factors influencing long-term opioid use among opioid naive patients: an examination of initial prescription characteristics and pain etiologies. J Pain. 2017;18:1374-1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SR, Bido J, Collins JE, Yang H, Katz JN, Losina E. Impact of preoperative opioid use on total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am . 2017;99:803-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stambough JB, Nunley RM, Curry MC, Steger-May K, Clohisy JC. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:521-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiser MC, Kim KY, Anoushiravani AA, Iorio R, Davidovitch RI. Outpatient total hip arthroplasty has minimal short-term complications with the use of institutional protocols. J Arthroplasty. 2018;33:3502-3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]