Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has caused the greatest worldwide pandemic since the 1918 flu. The consequences of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) are devastating and represent the current major public health issue across the globe. At the onset, SARS-CoV-2 primarily attacks the respiratory system as it represents the main point of entry in the host, but it also can affect multiple organs. Although most of the patients do not present symptoms or are mildly symptomatic, some people infected with SARS-CoV-2 that experience more severe multiorgan dysfunction. The severity of COVID-19 is typically combined with a set of comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and/or advanced age that seriously exacerbates the consequences of the infection. Also, SARS-CoV-2 can cause gastrointestinal symptoms, such as vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal pain during the early phases of the disease. Intestinal dysfunction induces changes in intestinal microbes, and an increase in inflammatory cytokines. Thus, diagnosing gastrointestinal symptoms that precede respiratory problems during COVID-19 may be necessary for improved early detection and treatment. Uncovering the composition of the microbiota and its metabolic products in the context of COVID-19 can help determine novel biomarkers of the disease and help identify new therapeutic targets. Elucidating changes to the microbiome as reliable biomarkers in the context of COVID-19 represent an overlooked piece of the disease puzzle and requires further investigation.

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ACE2, Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II; CNS, central nervous system; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; CPR, C-reactive protein; H1N1, influenza A virus; IL, Interleukin; MERS, Middle East respiratory syndrome; PRS, proteomic risk score; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SCFA, short-chain fatty acids; RAS, renin-angiotensin system; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; RT-PCR, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction; TMPRSS2, transmembrane serine protease 2; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor alpha

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), also called 2019-nCoV, arose in the province of Wuhan (China) in December 2019. SARS-CoV-2 causes severe respiratory disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1 On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization determined that the outbreak of a novel coronavirus had reached pandemic levels. As of August 12, 2020, there are over 20 million confirmed cases worldwide, with more than 740,000 associated global deaths, according to Johns Hopkins University.2 Over the last 9 months, the global population has been facing problems that impact both world health and global socioeconomics.3 COVID-19 has been, and continues to be, the focus of concern in a society threatened by the most destructive pandemic since the 1918 flu. Transmission, symptoms, vaccines, and treatments for COVID-19 continue to be investigated, hiding too many unknowns. The immediate strategy to curb the spread of this virus has been to recommend that people carry out a “social vaccination,” which involves restricting social gatherings, minimizing public appearances, telecommuting, implementing social distancing, or wear masks as much as possible. This is based on the high transmission ability of the SARS-CoV-2 via large respiratory droplets4 and by airborne routes.5 Unlike other viruses in the coronavirus family, SARS-CoV-2 infects people who then have little or no symptoms.6 Despite all this, asymptomatic COVID-19 positive individuals can spread the virus.7 This silent transmission capacity is the main reason this virus continues to transmit and infect the global population in an accelerated and uncontrollable way, in spite of best efforts to control and curb spread. Asymptomatic people manage to eliminate the virus without developing typical COVID-19 symptoms, and this suggests to us that the immune system is relevant and may have the key to beat the coronavirus. COVID-19 affects not only the respiratory and cardiovascular systems but also to the central nervous system (CNS) and gastrointestinal system.8 The objective of this review article is to examine whether the SARS-CoV-2 infection linked to gastrointestinal changes, may be linked to specific phases of COVID-19 associated to inflammation. We will also explore the studies on microbiome profiling intestinal immune system in the patients with COVID-19. This review will provide insights for microbiota modification therapy in the early stages of COVID-19, beyond antiviral and anti-inflammatory approaches. New therapeutic interventions might be possible through the restoration of the gut microbiome of individuals infected by SARS-CoV-2 to mitigate systemic inflammation, intestinal damage, and limit the effects caused in the CNS through the brain-gut axis.

Early and Late Stage of the Infection of SARS-CoV-2

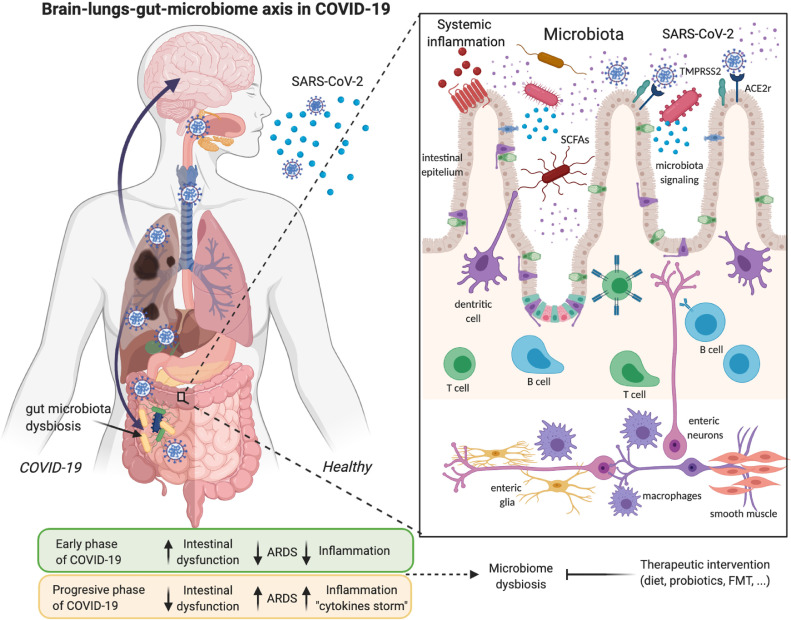

A multitude of epidemiological studies describe different phases in the development of COVID-19. The early or viral phase, shortly after infection, marked by a high viral load and a reduced inflammatory activity, with hardly any symptoms, and which is also associated with gastrointestinal illness (Fig 1 ). Besides, patients with COVID-19 who had the highest viral load levels at the beginning of the infection and subsequently decreased over time could explain the rapid spread of the disease.9 , 10 During the progressive or late phase of infection, COVID-19 positive individuals develop most severe symptoms like respiratory problems and fever. Immune cells like neutrophils, infiltrating monocytes, and macrophages produce inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species. Also, respiratory manifestations such as cough, sputum production and shortness of breath remain the most common symptoms, following fever or pneumonia.11 , 12 In a study with 102 COVID-19 patients, serum level of cytokines as interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10 were indicators of disease severity, showing that high levels of proinflammatory cytokine storm were associated with more severe disease development.13 Some patients with COVID-19 had severe complications, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, cardiovascular conditions, multiple organ dysfunction syndromes, or septic shock. These complications are related to the release of cytokines and hyperinflammation or “cytokine storm syndrome”14 (Fig. 1). A person is more infectious in the initial phase when the symptomatology of the disease does not manifest itself with respiratory symptoms, and however, the pre-symptomatic transmission may play an important role.7 Nevertheless, detecting SARS-CoV-2 infection in those without fever and/or respiratory symptoms is difficult because SARS-CoV-2 tests are not usually performed in infected people without these symptoms.

Fig 1.

Illustrative model of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its association with the lung-gut-brain axis and microbiome dysbiosis. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II (ACE2) and transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) are expressed multiple human host tissues, including the esophagus, lungs, liver, kidneys, brain, colon, or small intestine epithelium. SARS-CoV-2 activates intestinal ACE2 receptors, induces inflammation (enteritis), and, ultimately, diarrhea. These tissues are the targets of SARS-CoV-2, which goes through an early phase of infection where a high viral load induces intestinal problems. At the same time, the microbiome dysbiosis takes place by altering the T and B cells of the intestinal immune system, as well as the activation of the enteric system that sends inflammatory signals to the circulatory current or other organs, including the brain. In the second phase of COVID-19 or a continuous phase where acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) appears, the intestinal symptoms decrease, but the inflammation from the cytokines storm increases considerably. Created with Biorender.com

In summary, a subset of the symptoms associated with COVID-19 during the initial phase are intestinal complications, such as vomiting or diarrhea. Detecting these symptoms might not only lead to slowdown in transmission but also open the door to novel treatments that could reduce the severity of COVID-19. More studies are necessary to interpret the phases of the disease correctly, and especially if the viral load detected is considered infectious, and how it is related to respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 Patients With Digestive Symptoms and Intestinal Inflammation

COVID-19 is an emerging infection that causes great concern about respiratory manifestations. Furthermore, diarrhea and other gastrointestinal symptoms are frequently observed in patients with COVID-19,15 however the significance remains undetermined. A viral infection causes an alteration of intestinal permeability, resulting in enterocyte dysfunction.16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 When we investigate what happened with another coronavirus, we found that diarrhea was a frequent symptom in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) patients, occurring in 40%.23 Intestinal problems were also associated with the severity of the infection. Patients with diarrhea had an increased need for respiratory assistance and intensive care. SARS-CoV was also identified in ileal and terminal colonic biopsies.23 Regarding Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), several studies showed the presence of diarrhea between 14% and 50% of known cases.24, 25, 26 However, a less severe prognosis of the disease was observed in MERS patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.

The first results linking intestinal problems with COVID-19 were obtained from patients in Wuhan, China. Two hundred four patients with COVID-19 presented at three hospitals indicate that the majority of COVID-19 patients had typical respiratory symptoms. However, many patients infected with the coronavirus complained of digestive symptoms, such as diarrhea.27 There is no evidence on the efficacy of antidiarrheal drugs, but adequate rehydration and potassium monitoring were performed as in all COVID-19 patients. Thus, diarrhea should generate awareness of a possible SARS-CoV-2 infection and should be investigated to reach an early diagnosis of COVID-19. This factor should be considered when suspecting whether the patients are infected, instead of waiting for respiratory symptoms to appear, which would give us an earlier diagnosis. Patients with COVID-19, specifically those with digestive symptoms, remained a long time from onset to hospital admission and a worse clinical outcome, compared to patients who did not suffer from these symptoms.27 Likewise, patients with digestive symptoms had an average time of 9 days from the onset of symptoms until admission, while patients with respiratory symptoms had an admission time of 7.3 days.27 This may indicate that those with digestive symptoms waited longer to be diagnosed in the hospital, as they did not suspect they were SARS-CoV-2 positive in the absence of respiratory symptoms. Authors also state that patients with digestive symptoms presented clinical manifestations such as anorexia, diarrhea, vomiting, or abdominal pain. As the severity of the disease increased, gastrointestinal symptoms became more pronounced, but especially the high percentage, 83%, of patients admitted with symptoms of anorexia.27 One study indicated that COVID-19 patients experienced gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea (24.2%), anorexia (17.9%), and nausea (17.9%).21 However, the underlying pathophysiology gastrointestinal is not well understood. Another study analyzed 73 hospitalized patients, and some of them showed mild initial gastrointestinal symptoms, such as diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which preceded the characteristic fever, and respiratory problems such as dry cough. Diarrhea was reported in 26 patients, and the fecal test remained positive until 12 days after the disease onset; in 17 patients (23.3%), the stool test was still positive despite negative respiratory tests.28 In another study of 206 patients with low severity of COVID-19, including 48 presenting digestive symptoms alone, showed that patients with gastrointestinal symptoms had a longer duration between symptom onset and viral clearance and fecal virus-positive than those with respiratory symptoms.29 A systematic meta-analysis showed results from clinical studies with an incidence rate of diarrhea from as low as 2% and up to 50% of the positive cases.30 How is this disparity in the data possible? More clinical studies are required to elucidate the percentage of COVID-19 patients who develop intestinal symptoms and if these depend on other factors such as age, gender or other comorbidities.

Gastrointestinal symptoms are accompanied by inflammation or intestinal damage. There is a loss of intestinal barrier integrity and gut microbes that can activate innate and adaptive immune cells to release proinflammatory cytokines into the circulatory system, leading to systemic inflammation. Some intestinal signaling pathways can regulate inflammation through dendritic cells (Fig 1). Immunomodulation of the innate host immunity through the activation of epithelial receptors could represent a novel therapeutic target to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 in the early stage of the infection.31 The viral load of coronavirus appeared in the feces of 54% of the infected patients.32 An interaction between viral shedding of SARS-CoV-2 in stool has been reported, but its association with infection was yet to be determined. Identifying fecal coronavirus RNA may also lead researchers to ask new questions, is there transmission of the coronavirus found in fecal samples? What these researchers found is the presence of the coronavirus in the stool, but there is controversial studies about if viral load was infectious nor examples of transmission. Previously, a study involving 191 patients with COVID-19 reported that the median duration of viral shedding was 20 days in survivors (range, 8–37 days). Cultivable SARS-CoV-2 was detected in stool or urine specimens for longer than 4 weeks in three convalescent patients (29–36 days), suggesting that it may remain viable.33 Contradictorily, high SARS-CoV-2 titres detectable in the first week of illness with an early peak observed at symptom onset to day 5 of disease.9 , 34, 35, 36 Although SARS-CoV-2 RNA shedding can be prolonged, the duration of a viable virus is relatively short-lived.37

The presence of SARS-CoV-2 (including the virus with infectious capacity) in the feces of asymptomatic individuals implies that COVID-19 could be transmitted through the fecal route.38 SARS-CoV-2 shedding in stool samples is detectable over a longer period than in nasopharyngeal swabs. Donors for fecal microbiota transplant for SARS-CoV-2 must be strict and validated to prevent the potential risk of transmission.39 The results show that the elevated levels of fecal calprotectin in patients with COVID-19 add to the growing evidence that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes an inflammatory response in the intestine.40 Calprotectin concentrations were significantly higher in COVID-19 patients who had suffered from diarrhea and with more elevated serum IL-6 levels. In the diagnosis and especially in the follow-up of COVID-19-related diarrhea, the calprotectin measurement could play a potential role in monitoring the disease. Also, diarrhea may be secondary to virus-induced inflammation, which in turn is due to the entry of inflammatory cells into the intestinal mucosa, including neutrophils and lymphocytes, and thus disruption of the gut microbiota. Viral SARS-CoV-2 particles were detected in feces during the second phase of COVID-19, accompanied by a decrease in the peak of inflammation. Therefore, COVID-19-related inflammatory diarrhea was associated with reduced levels of fecal SARS-CoV-2 RNA.28 However, intestinal damage can manifest after respiratory symptoms, as reported in a clinical case, there may be a pathogenic role of SARS-CoV-2 on the gastrointestinal system.41 In Zheijiang (China), it was detected that half of the COVID-19 patients tested positive for reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in their feces, and intestinal microbial dysbiosis was also identified. Viral strains were isolated from feces, indicating potential infectiousness of feces.42 , 43 Another analysis conducted from 17 studies in China, United States, and Singapore had also detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in fecal specimens of patients at an average of 43%. This percentage is according to their clinical forecast, intestinal problems, or with more severe disease.44

Furthermore, the fecal test for SARS-CoV-2 RNA also bears a potential implication for physicians to decide the subsequent isolation strategies for those with positive fecal samples. The possibility of the fecal-oral route of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 should be investigated. All candidates for fecal microbiota transplantation and healthy donors should be screened for the virus.45 One could consider studies on the gut microbiome and its therapeutic role in transplanting feces in healthy donors to critically ill COVID-19 patients. Still, precautions should be taken because infectious SARS-CoV-2 particles are known to have been found in COVID-19 positive feces. The use of fecal transplants could be one of the immediate solutions in critically ill patients with a weakened immune system.

SARS-CoV-2 Interaction With Intestinal ACE2 Receptors

SARS-CoV-2 enters cells primarily through binding of protein S to Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme II (ACE2) receptors to infected cells.46 The central role of ACE2 in the cleavage of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a peptide involved in vascular homeostasis, vasomotor tone, and blood pressure regulation.47, 48, 49, 50 ACE2 receptors are expressed in various human cells susceptible to viral infection, including epithelial cells in the lungs, small intestine and colon, tubular cells of the kidney, neuronal and glial cells in the brain, enterocytes, vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and cardiomyocytes.51, 52, 53, 54 A recent study has reported on the expression pattern of ACE2 across more than 150 different cell types corresponding to all major human tissues and organs based on rigorous immunohistochemical analysis.55 SARS-CoV-2 also uses the receptors for transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMRPSS2), an enzyme that is also expressed in the small intestinal epithelial cells30 to entry to the infected cells (Fig 1). The SARS-CoV-2 activity could cause ACE2 modifications in the gut that increase susceptibility to intestinal inflammation and diarrhea. A high co-expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 was detected in enterocytes, and the esophagus and lungs.46 The co-expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 transcripts was highest in the small intestine, with 20% expressed in enterocytes and 5% in colon cells, as demonstrated by a single-cell RNA sequencing study in the gastrointestinal tract.56 ACE2 is not only playing an essential role in intestinal inflammation but also have a significant impact on the composition of the intestinal microbiota.57 ACE2 knockout mice have been shown to have decreased expression of antimicrobial peptides and exhibited altered intestinal microbial composition, which is restored by the administration of tryptophan.58 Likewise, it is known that there is a connection of transport of ACE2 amino acid with microbial ecology in the gut during SARS-CoV-2 infection.59 In another recent study using gnotobiotic (germ-free) rats was observed a decrease in ACE2 expression in the colon, that contributed to the pathology during COVID-19.60 There are numerous studies that have shown that by regulating the renin-angiotensin system (RAS), which includes ACE2, one can modulate systemic inflammation.61 Angiotensin II receptor blockers are widely used compounds that are therapeutically effective in cardiovascular disorders, renal disease, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes.61 Under normal healthy conditions, homeostasis of RAS-ACE2 occurs,62 while a perturbation to this system is observed in cardiovascular disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus.63, 64, 65 A reduction of ACE2 is associated with hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular problems, which represent the significant comorbidities of COVID-19.66 SARS-CoV-2 may potentially further upregulate RAS in cardiovascular patients and deplete ACE2. Downregulation of ACE2 levels in tissues has been linked to viral replication efficiency and pathogenicity,67 leading to the imbalance of positive and negative regulation of RAS. RAS-ACE2 imbalance in COVID-19 may greatly exacerbate tissue inflammation and may contribute to more adverse COVID-19 outcomes in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease and other comorbidities. ACE2 receptors may represent a target for COVID-19 treatments68 in patients with cardiovascular risk burden susceptible to conditions that worsen asymmetries in RAS/ACE2. However, suppression of ACE2-protective roles due to ACE2 depletion upon SARS-CoV-2 infection is very likely to uphold the poor outcomes observed in COVID-19 patients, especially in those with preexisting conditions. ACE2 also displays non-RAS-related roles linked with neutral amino acids transport and gut homeostasis. ACE2 has been implicated in the intestinal epithelium regulation of gut microbiota composition and function.69 In summary, ACE2 imbalance is likely a key player for the poor outcomes in the COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbidities and addresses a possible link for gut microbiota dysbiosis in this interplay.

The Effects of COVID-19 on the Gut Microbiome

Primary inflammatory stimuli trigger the release of microbial products and cytokines, which can cause microbial dysbiosis that can induce an inflammatory environment, releasing intestinal cytokines into the circulatory system, increasing the systemic inflammation of COVID-19. Taken together, a combined inflammation can potentially initiate an immune reaction that can create even more harm than the virus itself. It is necessary to know the host cytokine pathways and microbiota interactions with cytokine responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection to develop novel treatment approaches. It is essential to investigate how intestinal bacteria interact in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Among COVID-19 patients, an increase of a blood proteomic risk score (PRS) was associated with a risk of becoming a clinically severe infection. A recent study has shown more than 20 proteins in blood-related to the severity of COVID-19.70 These proteins included immune factors that are elevated during systemic inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP). Correlations between PRS and the intestinal microbiome might be associated with the severity of COVID-19. This new analysis would allow us to predict if the patient would develop more severe symptoms in the next days or weeks after the infection. Ruminococcus gnavus was identified in COVID-19 patients and positively correlated with inflammatory markers, while Clostridia was negatively correlated.70 Another small study of 15 patients hospitalized in Hong Kong has served to establish a gut microbiome profile in association with COVID-19 severity and changes in fecal shedding of SARS-CoV-2.71 Through the application of in-depth shotgun metagenomics analysis, the authors investigated longitudinal changes of the gut microbiome in COVID-19. The abundance of Coprobacillus, Clostridium ramosum, and Clostridium hathewayi correlated with COVID-19 severity, and it was observed an inverse correlation between the abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii (an anti-inflammatory bacterium). During the hospitalization time, were detected in COVID-19 patients; Bacteroides dorei, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides massiliensis, and Bacteroides ovatus, which downregulate the expression of ACE2 in the murine gut, correlating inversely with SARS-CoV-2 load in fecal samples.71 This study opens the doors to possible interventions for gut microbiota in hospitalized patients to reduce the severity of COVID-19. Another study of just 10 patients showed that the gut bacteria was associated with fecal SARS-CoV-2 load. The gut microbiome remained substantially different in hospitalized patients from that of healthy controls. A total of 14 bacterial species were identified to be significantly associated with the fecal viral load of SARS-CoV-2 across all fecal samples.72 This does not indicate that the gut microbiome is affected for long periods after recovery, and future therapeutic interventions would be necessary.

SARS-CoV-2 was detected in feces of 15 hospitalized patients with COVID-19, and the viral transcriptional activity was analyzed to determine the infectivity range associated with the gut microbiome. Fecal samples with a signature of high SARS-CoV-2 infectivity had higher abundances of bacterial species Collinsella aerofaciens, Collinsella tanakaei, Streptococcus infantis, and Morganella morganii. In contrast, fecal samples with a signature of low-to no SARS-CoV-2 infectivity had higher abundances of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) producing bacteria, Parabacteroides merdae, Bacteroides stercoris, Alistipes onderdonkii, and Lachnospiraceae bacterium. 73 However, live SARS-CoV-2 was not isolated from the feces COVID-19 patients. Another study of 30 COVID-19 patients showed a significantly reduced bacterial diversity, and a higher relative abundance.74 They compared these results with 25 influenza A virus subtype H1N1 patients who showed lower bacteria diversity compared with COVID-19 patients. Specific microbial signatures were identified in COVID-19 patients, which could help identify biomarkers that differentiate them from influenza A patients when there is a coinfection.72 Despite this, the phases of the disease were not established in this study.

Furthermore, in another study with 62 COVID-19 patients was found a reduced alpha diversity in microbes.75 The metatranscriptional analysis revealed that there were 36 differentially genes associated with immune pathways and cytokine signaling related to the diagnosis and severity of COVID-19, such as interferon-gamma signaling.74 Despite reporting interesting patterns, the studies mentioned above are not without limitations. The bioinformatics analysis employed in these studies does not guarantee species-level nor strain-level bacterial identification. Furthermore, no longitudinal analysis has been performed with the same patients to determine if these bacteria change after recovery from COVID-19. More studies that prospectively include infected but asymptomatic subjects, positive for SARS-CoV-2 but with different symptoms, would be necessary to establish a correlation with microbial markers or their products. Monitoring early in the disease, during early onset of COVID-19 and over the long-term will help to delineate the role of changes in the microbiome will be critically important to elucidating this connection further. Another major limitation is the small number of patients, and the absence of information about microbial changes in the context of COVID-19 that define broad groups of the population stratified by geography, ethnicity, gender, and/or age. To date, there are no metabolomics, or metaproteomic studies exploring the products of these bacteria and their function. By identifying microbial metabolites associated with COVID-19, we can understand what components these bacteria produce during COVID-19 that help us understand the influence of the communication pathways of the microbiota-gut-periphery axis relevant to the association between SARS-CoV-2 and hyperinflammation. Moreover, more studies investigating the correlation between SARS-CoV-2 and gut inflammation are necessary, including histopathology and molecular diagnostic assessments.

Comorbidities as Risk Factors for COVID-19 Associated With Loss of Microbial Diversity

SARS-CoV-2 can infect people of all ages, but older adults and people with preexisting medical conditions appear to be more vulnerable to becoming seriously ill.76 There are many hypotheses as to why this occurs. Still, one of the factors could be the loss of microbial diversity associated with aging and, with it, higher susceptibility to inflammation. Comorbidities play an essential role in determining the risk of severe complications and death after COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 comorbidities and risk factors include asthma, hypertension, smoking, male gender, or Alzheimer's disease or dementia.77 Changes in gut microbiota have been previously linked to all of these comorbidities, and this dysregulation could also be associated with changes in the immune system and the susceptibility to suffer more severe consequences of COVID-19 and gender-related differences in vulnerability to complications of COVID-19. Our microbiome changes as we age, which favors less diversity and a more significant inflammatory state. COVID-19 appears to be more dangerous in older people, men, and with comorbidities.78 The gut microbiota evolves during human life.79 The infant microbiota shows reduced diversity and will remain unstable for the first few years of experience until it becomes an adult-like microbiota.80 The gut microbiota within an individual is considered stable throughout adult life.81 In the elderly, gut microbiota diversity decreases, and dysbiosis increases and is associated with cognitive deficits, depression, and inflammatory markers.82 A change that is found repeatedly in the microbiota of the elderly is the decrease in the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes.81 , 83, 84, 85 Decreased bacterial diversity, as well as lower levels in specific bacterial groups, have also been observed in very elderly.84 , 86 , 87 At the genus and species level, the findings vary significantly between studies, although Bacteroides, Clostridium, and Lactobacillus appear recurrently altered in elderly individuals. Tragically, a high rate of COVID-19 fatalities is associated with groups of people over 80 years old.88 The causes may be the inability to overcome the infection, the weakness of the immune system, and the reduced microbiome diversity, causing the coronavirus to strongly attack this group of the population, causing a higher mortality rate. Another recent study has found significant associations between dietary patterns and measures of gut microbial composition in older men,89 the group of the population with the highest mortality rate from COVID-19.

Obesity is also associated with changes in the intestinal flora90 , 91 and is another risk factor in the severity of COVID-1992, 93, 94; therefore, another comorbidity in adults95 and children.96 In the United States, at least 25% of patients who die from COVID-19 have obesity, which is similar to the reported rates of cardiovascular disease in the same high-risk group (21%).97 It is necessary to study the relationship between obesity and the severity of the COVID-19 disease. Adipose tissue can serve as a reservoir for the spread of SARS-CoV-2, virus clearance, and systemic immune activation.98 Adipocytes in obese patients express higher levels of ACE2,99 and a reduction or elimination of already inflamed adipose tissue can reduce systemic viral spread, viral entry, and prolongation.100 In obese individuals, a marked dysregulation of myeloid and lymphoid responses within adipose tissue, is associated with dysregulation of cytokine profiles. Obese patients also have heightened levels of proinflammatory adipokines, leukotrienes, chemerin, among others, which may exacerbate their risk for cytokine storm syndrome and death.101 Alterations in the immune system result in changes in the intestinal flora, and coronavirus infection also induces bacterial changes that may alter the gut-brain axis. The intestinal flora plays a critical role in the regulation of neurological functions such as depression or anxiety.102 Surely the results of these studies allow us to know what the role of intestinal flora is in COVID-19 and its relationship with neurological problems at long term.103, 104, 105

Furthermore, diabetes is another disease associated with increased severity of symptoms and complications of COVID-19, and this can be attributed to systemic inflammation and gut-metabolite dysfunction.106 Individuals suffering from cardiovascular disease who become infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at increased risk of developing a worse prognosis of COVID-19 and also develop cardiovascular complications, including myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, stroke, or heart feature or myocardial suppression.107 Cardiovascular disease is accompanied by an imbalance of gut microbiota and a decreased microbiome diversity.108, 109, 110 Hypertension is likely to be influenced by diet, lifestyle factors, and microbiome.111 Notably, an increase in SCFA was previously associated with decreased blood pressure and improved arterial compliance.112

Changes in the Gut Microbiota Composition Through Diet to Deal With COVID-19

The impact of dietary patterns on susceptibility to and severity of infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus has been largely ignored to date. The commensal microbiome forms a dynamic environment that can be altered and cause dysbiosis from virus infection but can be positively modulated by diet components and probiotic treatments.113, 114, 115 Several studies show than an optimal immune response depends on proper diet and nutrition to control SARS-CoV-2 infection.71 , 116 In general, malnutrition can compromise the immune response, therefore affecting the vulnerability of the response to COVID-19. Consideration of the dietary and nutritional components, the factors during viral infection, can serve to strengthen the immune system for the prevention of infections, and a meaningful and balanced basis for an immune response is an adequate and balanced diet. Intake of a sufficient amount of protein is crucial for the production of antibodies. Also, a low level of vitamin A or zinc has been associated with an increased risk of infection. Branched-chain amino acids can maintain the hairy morphology of the intestines and increase intestinal immunoglobulin levels, thereby improving the intestinal barrier.117, 118, 119 Therefore, high-quality proteins are an essential component of an anti-inflammatory diet. Nutritional dietary components known to exert anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties include omega-3 fatty acids with high anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity, including vitamin C, vitamin E, and phytochemicals such as carotenoids and polyphenols that are widely present in plant-based foods.120, 121, 122, 123 Undoubtedly, omega-3 fatty acids appear to have the most potent anti-inflammatory capability. Several of these components can interact with cellular signaling components related to anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. An optimal state of proper nutrients to be capable reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, thus strengthening the immune system to protect us from the severity of COVID-19.124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129

There is much evidence linking vitamin D levels in the immune response to infection and the severity of COVID-19 reactions, as well as mortality. A study of older men with pre-existing conditions and below-normal vitamin D levels was associated with 13 times more likely to die of COVID-19. An adjustment in Vitamin D levels in the intake would also strengthen the immune system.130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136 Plant-based fiber has prebiotic effects such as promoting the growth of bacteria that are associated with health benefits, such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus spp. Moreover, reduce potential pathogens such as Clostridium spp. Adequate fiber intake has been shown to decrease the relative risk of mortality from infectious and respiratory diseases by 20%–40% and was associated with a lower risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.137 Intake of whole grains is also a more favorable intestinal microbiome composition, which reduces intestinal and systemic inflammation, and has been associated with a decrease in CRP, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). The fiber found in foods such as fruits, vegetables, or legumes has been associated with anti-inflammatory properties through fermentation by gut microbiota and the consequent formation of beneficial metabolic compounds. The metabolic subproducts produced by these bacteria, SCFA, together with acetate, propionate, butyrate, have anti-inflammatory properties (Fig 1). SCFAs bind to receptors on immune cells, suppress the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, increase the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and antioxidant enzymes.138, 139, 140 SCFAs also enhance the effector activity of CD8+ T cells by stimulating cellular metabolism (Fig 1).141

Gut microbiota-based approaches to reduced severity of the COVID-19

We must gain more knowledge in understanding the pathogenesis associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection and its effect on the gut microbiota. Healthy gut microbiota is rich in Bifidobacterium spp., Faecalibacterium spp., Ruminococcus spp. And Prevotella spp.142 That has been associated with low systemic inflammation. Probiotics are live microorganisms or beneficial bacteria that are used as a benefit for the health of the host, modulating the composition and function of the intestinal microbiota. The use of prebiotics and probiotics to regulate the balance of the intestinal flora could be an effective treatment to reduce the risk of bacterial and viral infections.143 It would also be useful to investigate the effect of high-fiber diets and/or probiotics on the outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Design treatments for COVID-19 would be based on the administration of both probiotics and prebiotics, or nutrients that would replace the absent bacteria, thus preventing the risk of systemi infection. As it was described above, COVID-19 patients with intestinal microbial dysbiosis were detected in a study in Zheijiang (China), suggesting that a supportive nutritional therapy should be applied to these patients.42 , 43 China's National Health Commission recommended the use of probiotics for the treatment of patients with severe COVID-19 to preserve intestinal balance and to prevent secondary bacterial infections.144 The impact of probiotics should also be investigated in COVID-19, as some may help by interacting with the intestinal microbiota and modulating the immune system. It remains to be determined whether the detected changes in the bacterial flora may be indicative of the patient's susceptibility to the progression of the more severe disease or could even be modified to reverse the infection. Gut microbiota could represent a new therapeutic target and that probiotics could have a role in the management of COVID-19 patients. However, there is currently no evidence that can associate the efficacy of the use of probiotics in reducing symptoms or time of hospitalization. With an adequate probiotic cocktail, the inflammatory response resulting from SARS-CoV-2 infection could be significantly reduced, and we would reduce its severity. Despite this, not all probiotics have the same effect in each person, and the interaction of the administered bacterial microbes with the resistance should also be analyzed to have under control a harmonious interaction between both. Although we do not know if we are infected or if our intestinal flora has changed after infection, we should consider switching to an anti-inflammatory diet as preventive measures. Therapeutics with defined microbes will offer greater confidence in the power of the treatments, as well as risk mitigation for improved patients. Possible considerations for using the gut microbiome in COVID-19 as a diagnosis or therapeutic tool have not yet been explored.

Concluding Remarks

Despite hundreds of scientific publications and all the efforts in COVID-19 research over the past eight months, we still have many questions about the disease and effective treatment strategies. The vast number symptom-free transmitters of COVID-19, so-called silent, pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic individuals, makes this pandemic challenging to control. Therefore, identifying the symptoms and the different phases of the infection is a complicated but necessary task to slow expansion before the arrival of effective vaccines. Paying attention to intestinal symptoms and modifying or engineering intestinal microbes or their metabolic products in response to COVID-19, may represent useful therapeutic alternatives. If we uncover the mechanisms of entry of the coronavirus into the intestinal tract, and especially when we better understand disease progression, we will be able to design new treatments-based targeting gut microbiota that may be able to alleviate or reverse the results of the COVID-19. In our search for an immediate solution to the dysregulation of the immune system of COVID-19 patients, it would be to understand the characteristics of immunity associated with changes with the intestinal flora. In conclusion, analyzing the gut microbiome in the context of COVID-19, and exploring its modulation through diet, prebiotics, probiotics, or fecal transplants warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by an R21NS106640 (SV) grant from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), and Houston Methodist Research Institute. I would also like to thank all the members of the COVID-19 International Research Team (www.cov-irt.org) for their suggestions and support during the elaboration of this work. The author has read the journal's authorship agreement.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has read the journal's policy on disclosure of potential conflicts of interest and have none to declare.

References

- 1.Cao Y., Cai K., Xiong L. Coronavirus disease 2019: a new severe acute respiratory syndrome from Wuhan in China. Acta Virol. 2020;64:245–250. doi: 10.4149/av_2020_201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lwin M.O., Lu J., Sheldenkar A., et al. Global sentiments surrounding the COVID-19 Pandemic on Twitter: analysis of Twitter trends. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e19447. doi: 10.2196/19447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bajaj A., Purohit H.J. Understanding SARS-CoV-2: genetic diversity, transmission and cure in human. Indian J Microbiol. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12088-020-00869-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morawska L., Milton D.K. It is time to address airborne transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J., Huang J., Xiang D. Large SARS-CoV-2 outbreak caused by asymptomatic traveler. China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020:29. doi: 10.3201/eid2609.201798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavezzo E., Franchin E., Ciavarella C., et al. Suppression of a SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in the Italian municipality of Vo'. Nature. 2020;584:425–429. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2488-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baig A.M., Sanders E.C. Potential neuroinvasive pathways of SARS-CoV-2: Deciphering the spectrum of neurological deficit seen in coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) J Med Virol. 2020;3 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He X., Lau E.H.Y., Wu P., et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:672–675. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y., Yan L.M., Wan L., et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:656–657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30232-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azkur A.K., Akdis M., Azkur D., et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy. 2020;75:1564–1581. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokolowska M., Lukasik Z., Agache I., et al. Immunology of COVID-19: mechanisms, clinical outcome, diagnostics and perspectives - a report of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI) Allergy. 2020 doi: 10.1111/all.14462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Han H., Ma Q., Li C., et al. Profiling serum cytokines in COVID-19 patients reveals IL-6 and IL-10 are disease severity predictors. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:1123–1130. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1770129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catanzaro M., Fagiani F., Racchi M., Corsini E., Govoni S., Lanni C. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:84. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cipriano M., Ruberti E., Giacalone A. Gastrointestinal infection could be new focus for coronavirus diagnosis. Cureus. 2020;12:e7422. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chakraborty S., Basu A. The COVID-19 pandemic: catching up with the cataclysm. F1000 Faculty. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24963.1. Rev-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parasa S., Desai M., Thoguluva Chandrasekar V., et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and fecal viral shedding in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kopel J., Perisetti A., Gajendran M., Boregowda U., Goyal H. Clinical insights into the gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:1932–1939. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06362-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong L.J., Zhou M.Y., He X.Q., Wu Y., Xie X.L. The role of human coronavirus infection in pediatric acute gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:645–649. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000002752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li R.L., Chu S.G., Luo Y., Huang Z.H., Hao Y., Fan C.H. Atypical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:1265–1270. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i7.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin L., Jiang X., Zhang Z., et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020;69:997–1001. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin X., Lian J.S., Hu J.H., et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020;69:1002–1009. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leung W.K., To K.F., Chan P.K., et al. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus infection. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1011–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assiri A., Al-Tawfiq J.A., Al-Rabeeah A.A., et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho S.Y., Kang J.M., Ha Y.E., et al. MERS-CoV outbreak following a single patient exposure in an emergency room in South Korea: an epidemiological outbreak study. Lancet. 2016;388:994–1001. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30623-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garbati M.A., Fagbo S.F., Fang V.J., et al. A Comparative study of clinical presentation and risk factors for adverse outcome in patients hospitalised with acute respiratory disease due to MERS coronavirus or other causes. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan L., Mu M., Yang P., et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: a descriptive, cross-sectional, multicenter study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:766–773. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao F., Sun J., Xu Y., et al. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 in feces of patient with severe COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1920–1922. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han C., Duan C., Zhang S., et al. Digestive symptoms in COVID-19 patients with mild disease severity: clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing, and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:916–923. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Amico F., Baumgart D.C., Danese S., Peyrin-Biroulet L. Diarrhea during COVID-19 infection: pathogenesis, epidemiology, prevention, and management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:1663–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Golonka R.M., Saha P., Yeoh B.S., et al. Harnessing innate immunity to eliminate SARS-CoV-2 and ameliorate COVID-19 disease. Physiol Genomics. 2020;52:217–221. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00033.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie C., Jiang L., Huang G., et al. Comparison of different samples for 2019 novel coronavirus detection by nucleic acid amplification tests. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu D., Zhang Z., Jin L., et al. Persistent shedding of viable SARS-CoV in urine and stool of SARS patients during the convalescent phase. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24:165–171. doi: 10.1007/s10096-005-1299-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han M.S., Seong M.W., Kim N., et al. Viral RNA load in mildly symptomatic and asymptomatic children with COVID-19. Seoul. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim E.S., Chin B.S., Kang C.K., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection: a preliminary report of the first 28 patients from the Korean Cohort Study on COVID-19. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e142. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cevik M, Tate M, Lloyd O, Maraolo AE, Schafers J, Ho A. SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1 and MERS-CoV viral load dynamics, duration of viral shedding and infectiousness: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Sun X., Wang T., Cai D., et al. Cytokine storm intervention in the early stages of COVID-19 pneumonia. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020;53:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilcox M.H., McGovern B.H., Hecht G.A. The efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: current understanding and gap analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7 doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa114. ofaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazza S., Sorce A., Peyvandi F., Vecchi M., Caprioli F. A fatal case of COVID-19 pneumonia occurring in a patient with severe acute ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2020;69:1148–1149. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meini S., Zini C., Passaleva M.T., et al. Pneumatosis intestinalis in COVID-19. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2020;7 doi: 10.1136/bmjgast-2020-000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu K., Cai H., Shen Y., et al. [Management of COVID-19: the Zhejiang experience] Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49:147–157. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu K., Cai H., Shen Y., et al. [Management of corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19): the Zhejiang experience] Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2020;49:0. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2020.02.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong M.C., Huang J., Lai C., Ng R., Chan F.K.L., Chan P.K.S. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in fecal specimens of patients with confirmed COVID-19: a meta-analysis. J Infect. 2020;81:e31–e38. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ianiro G., Mullish B.H., Kelly C.R., et al. Screening of faecal microbiota transplant donors during the COVID-19 outbreak: suggestions for urgent updates from an international expert panel. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:430–432. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30082-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mirabito Colafella K.M., Bovee D.M., Danser A.H.J. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and its therapeutic targets. Exp Eye Res. 2019;186 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2019.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mendoza-Torres E., Oyarzun A., Mondaca-Ruff D., et al. ACE2 and vasoactive peptides: novel players in cardiovascular/renal remodeling and hypertension. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;9:217–237. doi: 10.1177/1753944715597623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calo L.A., Schiavo S., Davis P.A., et al. ACE2 and angiotensin 1-7 are increased in a human model of cardiovascular hyporeactivity: pathophysiological implications. J Nephrol. 2010;23:472–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuba K., Imai Y., Penninger J.M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in lung diseases. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:271–276. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fandriks L. The angiotensin II type 2 receptor and the gastrointestinal tract. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2010;11:43–48. doi: 10.1177/1470320309347788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fandriks L. The renin-angiotensin system and the gastrointestinal mucosa. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;201:157–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feng Q., Liu D., Lu Y., Liu Z. The Interplay of renin-angiotensin system and toll-like receptor 4 in the inflammation of diabetic nephropathy. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6193407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garg M., Angus P.W., Burrell L.M., Herath C., Gibson P.R., Lubel J.S. Review article: the pathophysiological roles of the renin-angiotensin system in the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:414–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04971.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hikmet F., Mear L., Edvinsson A., Micke P., Uhlen M., Lindskog C. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16:e9610. doi: 10.15252/msb.20209610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee J.J., Kopetz S., Vilar E., Shen J.P., Chen K., Maitra A. Relative abundance of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the enterocytes of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Genes (Basel) 2020;11:645. doi: 10.3390/genes11060645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cole-Jeffrey C.T., Liu M., Katovich M.J., Raizada M.K., Shenoy V. ACE2 and microbiota: emerging targets for cardiopulmonary disease therapy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2015;66:540–550. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hashimoto T., Perlot T., Rehman A., et al. ACE2 links amino acid malnutrition to microbial ecology and intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2012;487:477–481. doi: 10.1038/nature11228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen L., Li X., Chen M., Feng Y., Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116:1097–1100. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang T., Chakraborty S., Saha P., et al. Gnotobiotic rats reveal that gut microbiota regulates colonic mRNA of Ace2, the receptor for SARS-CoV-2 infectivity. Hypertension. 2020;76:e1–e3. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.15360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villapol S., Saavedra J.M. Neuroprotective effects of angiotensin receptor blockers. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:289–299. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tikellis C., Thomas M.C. Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) is a key modulator of the renin angiotensin system in health and disease. Int J Pept. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/256294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tikellis C., Brown R., Head G.A., Cooper M.E., Thomas M.C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 mediates hyperfiltration associated with diabetes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F773–F780. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00264.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tikellis C., Bernardi S., Burns W.C. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a key modulator of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiovascular and renal disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2011;20:62–68. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328341164a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garg M., Royce S.G., Tikellis C., et al. Imbalance of the renin-angiotensin system may contribute to inflammation and fibrosis in IBD: a novel therapeutic target? Gut. 2020;69:841–851. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-318512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magrone T., Magrone M., Jirillo E. Focus on receptors for coronaviruses with special reference to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 as a potential drug target - a perspective. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2020;20:807–811. doi: 10.2174/1871530320666200427112902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dijkman R., Jebbink M.F., Deijs M., et al. Replication-dependent downregulation of cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 protein expression by human coronavirus NL63. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:1924–1929. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043919-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Saavedra J.M. Angiotensin receptor blockers and COVID-19. Pharmacol Res. 2020;156 doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Perlot T., Penninger J.M. ACE2 - from the renin-angiotensin system to gut microbiota and malnutrition. Microbes Infect. 2013;15:866–873. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gou W F.Y., Yue L., Chen G.-D., et al. Gut microbiota may underlie the predisposition of healthy individuals to COVID-19. medRxiv. 2020 preprint. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zuo T., Zhan H., Zhang F., et al. Alterations in Fecal Fungal Microbiome of Patients With COVID-19 During Time of Hospitalization until Discharge. Gastroenterology. 2020;26 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.048. S0016-5085(20)34852-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo Y.R., Cao Q.D., Hong Z.S., et al. The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak - an update on the status. Mil Med Res. 2020;7:11. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zuo T., Liu Q., Zhang F., et al. Depicting SARS-CoV-2 faecal viral activity in association with gut microbiota composition in patients with COVID-19. Gut. 2020;20 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322294. gutjnl-2020-322294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gu S., Chen Y., Wu Z., et al. Alterations of the gut microbiota in patients with COVID-19 or H1N1 Influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;4 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa709. ciaa709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang H., Ai J.W., Yang W., et al. Metatranscriptomic characterization of COVID-19 identified a host transcriptional classifier associated with immune signaling. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;28 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa663. ciaa663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Esteve A., Permanyer I., Boertien D., Vaupel J.W. National age and coresidence patterns shape COVID-19 vulnerability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:16118–16120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008764117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Darbani B. The expression and polymorphism of entry machinery for COVID-19 in human: juxtaposing population groups, gender, and different tissues. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:3433. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17103433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fuchs B.B., Tharmalingam N., Mylonakis E. Vulnerability of long-term care facility residents to Clostridium difficile infection due to microbiome disruptions. Future Microbiol. 2018;13:1537–1547. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2018-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Romano-Keeler J., Moore D.J., Wang C., et al. Early life establishment of site-specific microbial communities in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2014;5:192–201. doi: 10.4161/gmic.28442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yatsunenko T., Rey F.E., Manary M.J., et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486:222–227. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Claesson M.J., Cusack S., O'Sullivan O., et al. Composition, variability, and temporal stability of the intestinal microbiota of the elderly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4586–4591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000097107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wiley N.C., Dinan T.G., Ross R.P., Stanton C., Clarke G., Cryan J.F. The microbiota-gut-brain axis as a key regulator of neural function and the stress response: Implications for human and animal health. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:3225–3246. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mariat D., Firmesse O., Levenez F., et al. The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zwielehner J., Liszt K., Handschur M., Lassl C., Lapin A., Haslberger A.G. Combined PCR-DGGE fingerprinting and quantitative-PCR indicates shifts in fecal population sizes and diversity of Bacteroides, bifidobacteria and Clostridium cluster IV in institutionalized elderly. Exp Gerontol. 2009;44:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Makivuokko H., Tiihonen K., Tynkkynen S., Paulin L., Rautonen N. The effect of age and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on human intestinal microbiota composition. Br J Nutr. 2010;103:227–234. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hopkins M.J., Macfarlane G.T. Changes in predominant bacterial populations in human faeces with age and with Clostridium difficile infection. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:448–454. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-5-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Woodmansey E.J., McMurdo M.E., Macfarlane G.T., Macfarlane S. Comparison of compositions and metabolic activities of fecal microbiotas in young adults and in antibiotic-treated and non-antibiotic-treated elderly subjects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:6113–6122. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.10.6113-6122.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Porcheddu R., Serra C., Kelvin D., Kelvin N., Rubino S. Similarity in Case Fatality Rates (CFR) of COVID-19/SARS-COV-2 in Italy and China. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14:125–128. doi: 10.3855/jidc.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shikany J.M., Demmer R.T., Johnson A.J., et al. Association of dietary patterns with the gut microbiota in older, community-dwelling men. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;110:1003–1014. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqz174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sanz Y., Moya-Perez A., Microbiota inflammation and obesity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;817:291–317. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0897-4_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sanmiguel C., Gupta A., Mayer E.A. Gut microbiome and obesity: a plausible explanation for obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4:250–261. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Briand-Mesange F., Trudel S., Salles J., Ausseil J., Salles J.P., Chap H. Silver Spring; Obesity: 2020. Possible Role of Adipose Tissue and Endocannabinoid System in COVID-19 Pathogenesis: Can Rimonabant Return? [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Michalakis K., Ilias I. SARS-CoV-2 infection and obesity: common inflammatory and metabolic aspects. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:469–471. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kassir R. Risk of COVID-19 for patients with obesity. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13034. doi: 10.1111/obr.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gupta R., Misra A. Contentious issues and evolving concepts in the clinical presentation and management of patients with COVID-19 infectionwith reference to use of therapeutic and other drugs used in Co-morbid diseases (Hypertension, diabetes etc) Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nogueira-de-Almeida C.A., Ciampo L.A.D., Ferraz I.S., Ciampo I., Contini A.A., Ued F.D.V. COVID-19 and obesity in childhood and adolescence: A clinical review. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de Lucena T.M.C., da Silva Santos A.F., de Lima B.R., de Albuquerque Borborema M.E., de Azevedo Silva J. Mechanism of inflammatory response in associated comorbidities in COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:597–600. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Malavazos A.E., Corsi Romanelli M.M., Bandera F., Iacobellis G. Targeting the Adipose Tissue in COVID-19. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1178–1179. doi: 10.1002/oby.22844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Tan M., He F.J., MacGregor G.A. Obesity and covid-19: the role of the food industry. BMJ. 2020;369:m2237. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ryan P.M., Caplice N.M. Is adipose tissue a reservoir for viral spread, immune activation, and cytokine amplification in Coronavirus disease 2019? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28:1191–1194. doi: 10.1002/oby.22843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mancuso P. The role of adipokines in chronic inflammation. Immunotargets Ther. 2016;5:47–56. doi: 10.2147/ITT.S73223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fung T.C., Olson C.A., Hsiao E.Y. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:145–155. doi: 10.1038/nn.4476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lei Z., Cao H., Jie Y., et al. A cross-sectional comparison of epidemiological and clinical features of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Wuhan and outside Wuhan. China. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rogers J.P., Chesney E., Oliver D., et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:611–627. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30203-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Serrano-Castro P.J., Estivill-Torrus G., Cabezudo-Garcia P., et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases: a delayed pandemic? Neurologia. 2020;35:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2020.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Heintz-Buschart A., May P., Laczny C.C., et al. Integrated multi-omics of the human gut microbiome in a case study of familial type 1 diabetes. Nat Microbiol. 2016;2:16180. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Teuwen L.A., Geldhof V., Pasut A., Carmeliet P. COVID-19: the vasculature unleashed. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:389–391. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0343-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Anselmi G., Gagliardi L., Egidi G., et al. Gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases: a critical review. Cardiol Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1097/CRD.0000000000000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Jayachandran M., Chung S.S.M., Xu B. A critical review on diet-induced microbiota changes and cardiovascular diseases. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019:1–12. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1666792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Novakovic M., Rout A., Kingsley T., et al. Role of gut microbiota in cardiovascular diseases. World J Cardiol. 2020;12:110–122. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v12.i4.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Louca P., Menni C., Padmanabhan S. Genomic determinants of hypertension with a focus on metabolomics and the gut microbiome. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:473–481. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpaa022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chen L., He F.J., Dong Y., et al. Modest sodium reduction increases circulating short-chain fatty acids in untreated hypertensives: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Hypertension. 2020;76:73–79. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.120.14800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ashuro A.A., Lobie T.A., Ye D.Q., et al. Review on the alteration of gut microbiota: the role of HIV Infection and old age. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2020;36:556–565. doi: 10.1089/aid.2019.0282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Illiano P., Brambilla R., Parolini C. The mutual interplay of gut microbiota, diet and human disease. FEBS J. 2020;287:833–855. doi: 10.1111/febs.15217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sirisinha S. The potential impact of gut microbiota on your health: current status and future challenges. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2016;34:249–264. doi: 10.12932/AP0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zuo T., Zhang F., Lui G.C.Y., et al. Alterations in gut microbiota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterology. 2020;20 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.048. S0016-5085(20)34701-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Elmadfa I., Meyer A.L. The Role of the Status of Selected Micronutrients in Shaping the Immune Function. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2019;19:1100–1115. doi: 10.2174/1871530319666190529101816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schofield C., Ashworth A. Severe malnutrition in children: high case-fatality rates can be reduced. Afr Health. 1997;19:17–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Giorgi P.L., Catassi C., Guerrieri A. [Zinc and chronic enteropathies] Pediatr Med Chir. 1984;6:625–636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Allison D.J., Beaudry K.M., Thomas A.M., Josse A.R., Ditor D.S. Changes in nutrient intake and inflammation following an anti-inflammatory diet in spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2019;42:768–777. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2018.1519996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tucker K.L. Vegetarian diets and bone status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(Suppl 1):329S–335S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.071621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.McAfee A.J., McSorley E.M., Cuskelly G.J., et al. Red meat consumption: an overview of the risks and benefits. Meat Sci. 2010;84:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Keysser G. [Are there effective dietary recommendations for patients with rheumatoid arthritis?] Z Rheumatol. 2001;60:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s003930170094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Zabetakis I., Lordan R., Norton C., Tsoupras A. COVID-19: the inflammation link and the role of nutrition in potential mitigation. Nutrients. 2020;12:1466. doi: 10.3390/nu12051466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.San K.M.M., Fahmida U., Wijaksono F., Lin H., Zaw K.K., Htet M.K. Chronic low grade inflammation measured by dietary inflammatory index and its association with obesity among school teachers in Yangon, Myanmar. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2018;27:92–98. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.042017.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Owczarek D., Rodacki T., Domagala-Rodacka R., Cibor D., Mach T. Diet and nutritional factors in inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:895–905. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i3.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Santillo V.M., Lowe F.C. Role of vitamins, minerals and supplements in the prevention and management of prostate cancer. Int Braz J Urol. 2006;32:3–14. doi: 10.1590/s1677-55382006000100002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Tucker G. Nutritional enhancement of plants. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14:221–225. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(03)00031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.White-O'Connor B., Sobal J. Nutrient intake and obesity in a multidisciplinary assessment of osteoarthritis. Clin Ther. 1986;9(Suppl B):30–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Quesada-Gomez J.M., Castillo M.E., Bouillon R. Vitamin D Receptor stimulation to reduce Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) in patients with Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 infections: Revised Ms SBMB 2020_166. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ribeiro H., Santana K.V.S., Oliver S.L., et al. Does Vitamin D play a role in the management of Covid-19 in Brazil? Rev Saude Publica. 2020;54:53. doi: 10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054002545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Aygun H. Vitamin D can prevent COVID-19 infection-induced multiple organ damage. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2020;393:1157–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00210-020-01911-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Mitchell F. Vitamin-D and COVID-19: do deficient risk a poorer outcome? Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:570. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30183-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hastie C.E., Mackay D.F., Ho F., et al. Vitamin D concentrations and COVID-19 infection in UK Biobank. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:561–565. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Hemila H., Chalker E. Vitamin C as a possible therapy for COVID-19. Infect Chemother. 2020;52:222–223. doi: 10.3947/ic.2020.52.2.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Molloy E.J., Murphy N. Vitamin D, Covid-19 and Children. Ir Med J. 2020;113:64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Baud D., Dimopoulou Agri V., Gibson G.R., Reid G., Giannoni E. Using probiotics to flatten the curve of coronavirus disease COVID-2019 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:186. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Lombardi V.C., De Meirleir K.L., Subramanian K., et al. Nutritional modulation of the intestinal microbiota; future opportunities for the prevention and treatment of neuroimmune and neuroinflammatory disease. J Nutr Biochem. 2018;61:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Mohajeri M.H., Brummer R.J.M., Rastall R.A., et al. The role of the microbiome for human health: from basic science to clinical applications. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s00394-018-1703-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Patterson E., Cryan J.F., Fitzgerald G.F., Ross R.P., Dinan T.G., Stanton C. Gut microbiota, the pharmabiotics they produce and host health. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73:477–489. doi: 10.1017/S0029665114001426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Trompette A., Gollwitzer E.S., Pattaroni C., Lopez-Mejia I.C., Riva E., Pernot J., et al. Dietary fiber confers protection against flu by shaping Ly6c(-) patrolling monocyte hematopoiesis and CD8(+) T cell metabolism. Immunity. 2018;48:992–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.022. e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Hills R.D., Jr., Pontefract B.A., Mishcon H.R., Black C.A., Sutton S.C., Theberge C.R. Gut microbiome: profound implications for diet and disease. Nutrients. 2019;11:1613. doi: 10.3390/nu11071613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Conte L., Toraldo D.M. Targeting the gut-lung microbiota axis by means of a high-fibre diet and probiotics may have anti-inflammatory effects in COVID-19 infection. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2020;14 doi: 10.1177/1753466620937170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Gao Q.Y., Chen Y.X., Fang J.Y. 2019 Novel coronavirus infection and gastrointestinal tract. J Dig Dis. 2020;21:125–126. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]