Abstract

Background:

Left atrioventricular valvar regurgitation (LAVVR) following atrioventricular canal (AVC) repair remains a significant cause of morbidity. Papillary muscle arrangement may be important. The implications of left mural leaflet morphology have not been investigated. We examined anatomic characteristics of the LAVV to determine possible associations with postoperative LAVVR.

Methods:

All patients with biventricular AVC repair at our institution between 1/1/11 and 12/31/16 with necessary imaging were retrospectively reviewed. Papillary muscle structure and novel measures of the left mural leaflet were assessed from preoperative echocardiograms, and degree of LAVVR from the first and last available follow-up echocardiograms. Associations with degree of early and late postoperative LAVVR were assessed with t-tests, ANOVA or Chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests, and multivariable logistic regression.

Results:

Fifty-eight patients (37% of 156) had significant (moderate or severe) early postoperative LAVVR. Thirty (32% of 93) had significant LAVVR after 6 or more months. Fewer patients with closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles had moderate or severe late LAVVR versus those with widely-spaced papillary muscles (17% versus 40%, P=0.019). Controlling for weight at surgery, genetic syndromes and bypass time, widely-spaced papillary muscles increased the odds ratio for late LAVVR to 3.6 (P=0.026). Larger mural leaflet area was also associated with late LAVVR on univariable and multivariable analyses (P=0.019; P=0.023). A third of patients with significant late LAVVR had no significant early postoperative regurgitation.

Conclusions:

Mural leaflet and papillary muscle anatomy are associated with late LAVVR after AVC repair. Late regurgitation can develop in the absence of early LAVVR, suggesting different mechanisms.

Left atrioventricular valve regurgitation (LAVVR) following repair of atrioventricular canal defect (AVC) remains a significant source of morbidity. Although surgical mortality in the current era is low, reintervention rates remain as high as 25% [1]. Younger age and lower weight at repair [2], preoperative [3], and early postoperative LAVVR [2] have been associated with increased risk of postoperative LAVVR, yet the underlying mechanisms remain unknown.

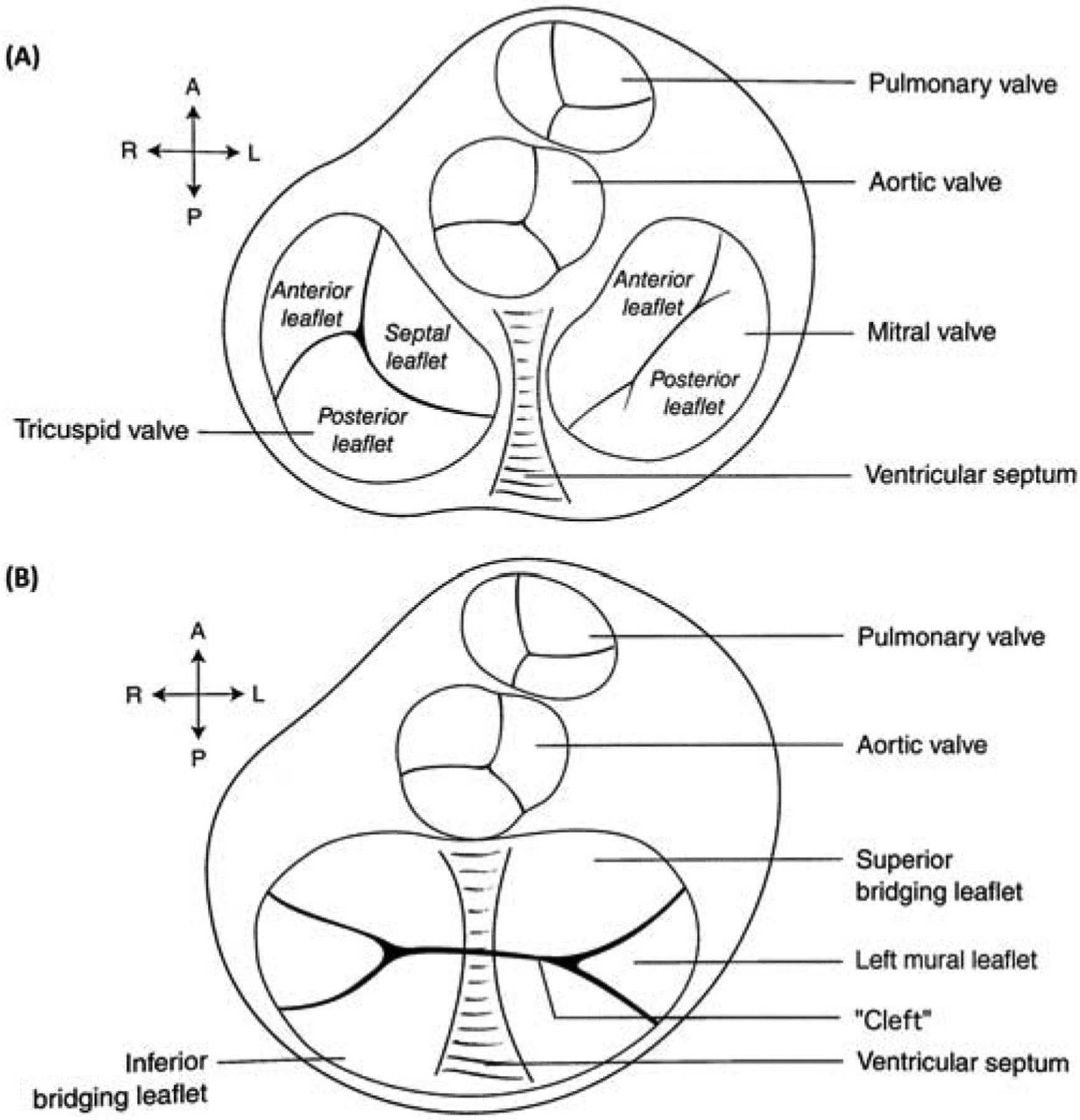

In AVC, the common valve has superior and inferior bridging leaflets that span across both ventricles. A “mural” leaflet completes the trifoliate left atrioventricular valve (LAVV, Figure 1). The papillary muscles in AVC are rotated counter-clockwise in the echocardiographic short axis view compared to normal, as they are positioned where the superior and inferior bridging leaflets meet the mural leaflet [4]. Closely-spaced papillary muscles have been associated with a diminutive left mural leaflet [5].

Figure 1.

(A) Cross-sectional view of the atrioventricular valves in a normal heart. (B) Superior and inferior bridging leaflets with left- and right-sided mural leaflets in atrioventricular canal defect. Diagrams used with permission, from Lai, Mertens, Cohen & Geva. Echocardiography in Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease: From Fetus to Adult. Wiley, 2016.

Recent investigations report that LAVV anomalies are associated with postoperative LAVVR. Prifti et al. noted LAVV malformations in 8 of 10 patients requiring reoperation for LAVVR [6]. Ando et al. reported an odds ratio of 4.97 for developing significant LAVV stenosis or regurgitation in the presence of abnormal papillary muscle anatomy [5]. There is conflicting evidence about the impact of papillary muscle anatomy on LAVVR; one study noted increased risk of postoperative LAVVR with closely spaced papillary muscles [5], while another reported lateral papillary muscle displacement as a factor [7].

We sought to characterize left mural leaflet and papillary muscle morphology in AVC, and to determine if variations in anatomy are risk factors for postoperative LAVVR. We hypothesized that mural leaflet size and papillary muscle architecture, being interrelated, would be associated with postoperative LAVVR severity.

Patients and Methods

This study is a single-center, retrospective review of all patients with complete or transitional AVC who underwent biventricular repair between 1/1/2011 and 12/31/2016 at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Patients were excluded if there was inadequate preoperative imaging, no postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram, dextrocardia (resulting in non-standard echocardiographic views), or major additional congenital heart defects such as double outlet right ventricle. The Institutional Review Board approved the study and waiver of need for patient consent.

Demographic, preoperative, operative, and postoperative information were collected from the surgical database and electronic medical record. Operative notes were reviewed. The earliest preoperative echocardiogram with the necessary images for measurement, and the first complete postoperative transthoracic echocardiogram were reviewed for each patient. If the patient had pulmonary artery banding, an echocardiogram from after the initial surgery was chosen to reflect the degree of valvar insufficiency prior to complete repair. If available, a third transthoracic echocardiogram from six months or more following surgery was also reviewed, either the most recent follow-up, or the last echocardiogram prior to reintervention.

From the preoperative echocardiogram, the type of AVC (complete vs. transitional) was recorded. Previously published measures were utilized to assess ventricular unbalance, including the modified AV valve index (LAVV area/total AV valve area), AV inflow index, and RV-LV inflow angle [8–12]. Pre- and postoperative AVVR was determined to be none/trivial, mild, moderate, or severe, and categorized as left or right AVVR, based on the location and size of the vena contracta and regurgitant jet. Presence or absence of AV valve stenosis was also noted.

LAVV Anatomic Assessment

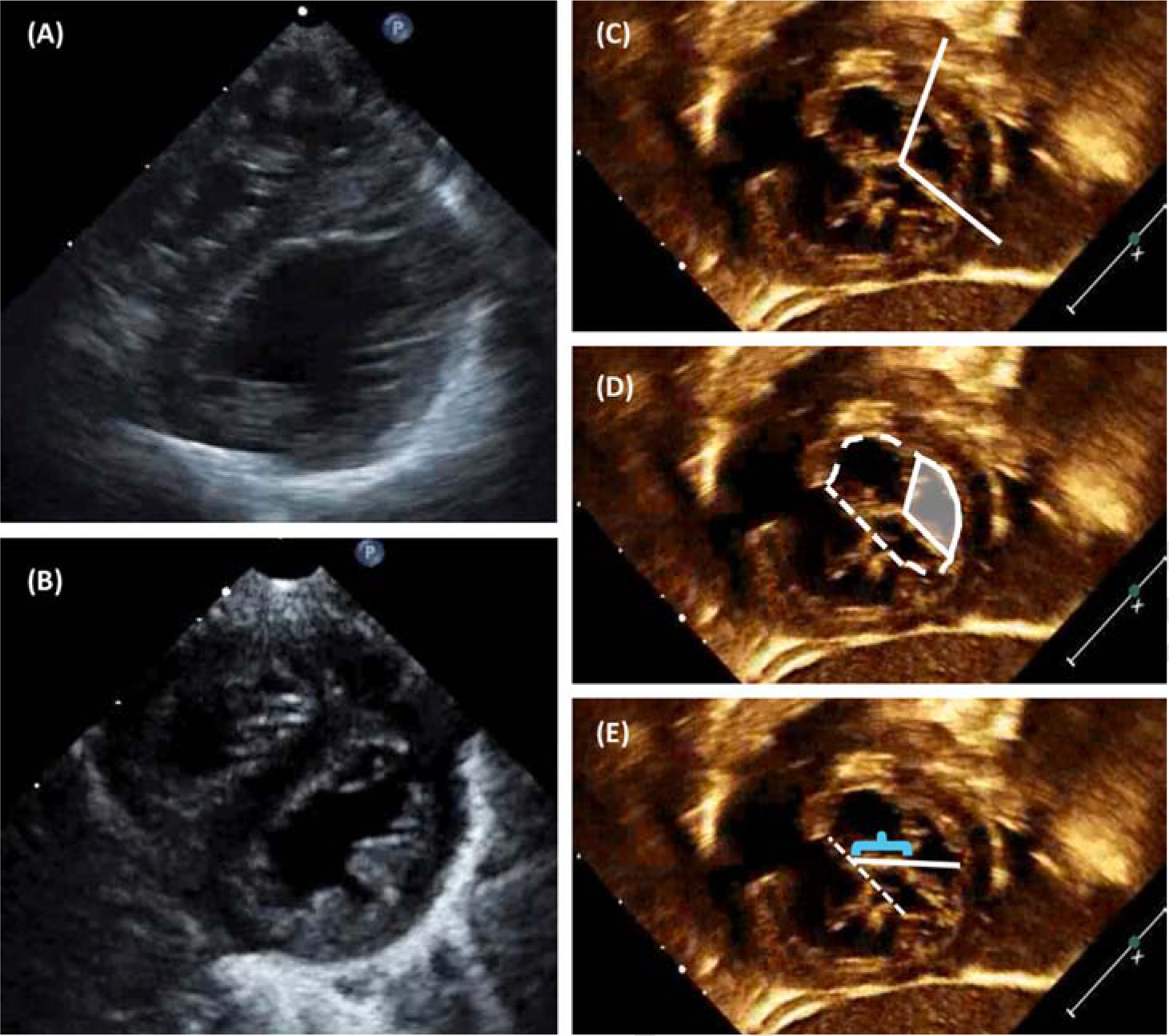

Papillary muscles were assessed from a parasternal short-axis view, and categorized as widely spaced, closely spaced, and/or asymmetric, when there was a dominant papillary muscle. Double-orifice LAVV was also recorded if noted on the echocardiogram or operative report. Papillary muscle characteristics were grouped in two ways. In our primary analysis, two categories were used: widely-spaced (n=110), versus closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles (n=46, Figure 2). Of the four patients with double-orifice LAVV, one had closely-spaced papillary muscles, and three had widely-spaced papillary muscles. In a secondary analysis, all four papillary muscle characteristic groups were compared, and patients who fit multiple descriptors were categorized by their “primary” anomaly. Three patients had closely-spaced and asymmetric papillary muscles, and were classified as asymmetric; one patient had both a double-orifice LAVV and closely spaced papillary muscles, and was categorized as double-orifice.

Figure 2.

Echocardiographic LAVV characteristics: (A) Parasternal long-axis view demonstrating widely-spaced papillary muscles, and (B) closely-spaced papillary muscles, one of which appears dominant. (C) Mural leaflet tip angle. (D) Mural leaflet area (shaded) as a percentage of the overall LAVV area (dashed outline). (E) Cleft length (bracket) as a percentage of the overall LAVV diameter (solid white line).

We developed three preoperative echocardiographic measures to describe left-sided mural leaflet morphology: angle of the leaflet tip, area of the mural leaflet as a proportion of the LAVV area, and length of the cleft as a proportion of the LV internal diameter (Figure 2). One investigator reviewed all echocardiograms and obtained all measurements, and the senior author (MC) reviewed 10% of the studies. Reproducibility of these measures was assessed using intraclass correlations.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics were reported using means/standard deviations or medians/interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Using t-tests/ANOVA/Wilcoxon rank sum tests or Chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests, we analyzed the association between the papillary muscle and mural leaflet characteristics, as well as the associations between these measures and the anatomic AVC characteristics, surgical characteristics, and postsurgical outcomes. Correlations were also computed. The literature suggests the LAVV remodels after surgery [13], which may affect LAVVR. To identify risk factors for long-term LAVVR, we performed a subgroup analysis on patients with postoperative follow-up echocardiograms 6 months or more following surgery. Associations between patient characteristics and early or late postoperative LAVVR were also examined.

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess the relationship between papillary muscle morphology or mural leaflet percentage and early or late LAVVR. Model 1 included widely versus closely-spaced papillary muscles, while Model 2 included mural leaflet area percentage. Both models adjusted for weight at surgery, presence or absence of genetic syndrome, and bypass time, which were chosen based on clinical significance and results of the univariable analyses.

Results

During the study period, 165 patients underwent biventricular repair. Of these, 156 (95%) had sufficient imaging and were included. The median time from surgery to the postoperative echocardiogram was 3 days (IQR: 2 days, 5 days). Median postoperative follow-up time was 1 year (IQR: 15 days, 3.6 years). Ninety-three patients (60%) had echocardiographic follow-up more than six months after surgery and were included in the subanalysis for long-term LAVVR. Median time from surgery to the last available follow-up echocardiogram in this subgroup was 2.3 years (IQR: 0.6 years, 4 years).

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. The majority of the cohort had Trisomy 21. Eighty-four percent had complete AVC. Fourteen percent had significant (moderate or severe) preoperative LAVVR. Median age at operation was 110.5 days (IQR 88, 169.5), at a median weight of 4.75kg (IQR 4.15, 5.65). Our institution favors a two-patch repair and cleft closure when feasible, which were performed in a majority of the cohort. Sixteen patients (10%) underwent LAVV reoperation or replacement. Eleven of 16 reoperations occurred within the first 3 months postoperatively. Four patients required two or more reoperations, and 3 underwent eventual mechanical valve replacement. Two additional patients required non-LAVV reoperations, for subaortic membrane resection, and severe right AV valve regurgitation with residual ventricular septal defect (VSD). Overall mortality during the study period was 4%. Fifty-eight patients (37%) had significant early postoperative LAVVR. In the long-term follow-up subgroup, 30 of 93 patients (32%) had significant LAVVR.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort (N=156).

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 87 | 55.8% |

| No genetic syndrome | 31 | 19.9% |

| Trisomy 21 | 121 | 77.6% |

| Other | 3 | 1.9% |

| Complete AVC | 131 | 84.0% |

| Preoperative LAVVR: moderate/severe | 22 | 14.1% |

| None/PDA/ASD/VSD | 131 | 84.0% |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | 10 | 6.4% |

| Coarctation/arch hypoplasia | 8 | 5.1% |

| Other | 7 | 4.5% |

| Age at operation (median days, IQR) | 110.5 | (88, 169.5) |

| Weight at operation (median kg, IQR) | 4.75 | (4.15, 5.65) |

| Two-patch technique | 115 | 73.7% |

| No cleft closure | 14 | 9.0% |

| Partial | 26 | 16.7% |

| Complete | 116 | 74.4% |

| Bypass time (mean minutes, SD) | 64.56 | (32.08) |

| Cross-clamp time (mean minutes, SD) | 48.02 | (22.61) |

| DHCA: yes | 6 | 3.8% |

| >1 bypass run | 16 | 10.3% |

| Reoperation/valve replacement | 16 | 10.3% |

| Deceased/transplant | 6 | 3.8% |

| Early postop LAVVR: moderate/severe | 58 | 37.2% |

| Late postop LAVVR: moderate/severe (Follow-up cohort N=90) | 30 | 32.3% |

LAVV Anatomy

Papillary muscle configuration was associated with mural leaflet tip angle and mural leaflet area percentage, but not cleft length (Table 2). Closely-spaced and asymmetric papillary muscles were associated with more acute mural leaflet tip angles and smaller leaflet areas. When comparing all four papillary muscle characteristics (widely spaced, closely spaced, asymmetric papillary muscles and double orifice LAVV), asymmetric papillary muscles were associated with the most acute mural leaflet tip angles and smallest mural leaflet areas.

Table 2.

Association between papillary muscle arrangement (in two and four subcategories) and mural leaflet morphology.

| Mural Leaflet Tip Angle | Mural leaflet area % | Cleft length % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | Mean | SD | p | |

| Widely spaced | 110 | 100.74 | 20.15 | 0.021 | 28.98 | 7.48 | 0.003 | 43.37 | 8.07 | 0.500 |

| Closely | 46 | 90.68 | 25.70 | 24.08 | 9.67 | 44.41 | 10.19 | |||

| Widely spaced | 107 | 100.7 | 20.34 | 0.040 | 28.97 | 7.48 | 0.015 | 43.39 | 8.18 | 0.757 |

| Closely spaced | 24 | 93.85 | 28.89 | 24.5 | 7.78 | 45.46 | 9.03 | |||

| Asymmetric | 21 | 86.37 | 22.02 | 23.91 | 11.77 | 43.17 | 11.71 | |||

| Double orifice | 4 | 101.65 | 11.89 | 26.38 | 6.53 | 43.31 | 2.33 | |||

Demographic and Anatomic Associations

There were no associations between the papillary muscle or mural leaflet characteristics and patient sex, genetic syndrome, or additional cardiac defects. The only significant anatomic association with papillary muscle structure was RV/LV inflow angle (Table 3).

Table 3.

Demographic and anatomic characteristics by papillary muscle configuration and mural leaflet measures. CC, correlation coefficient.

| Widely Spaced | Close/Asymmetric | Mural Leaflet Tip Angle | Mural leaflet area % | Cleft length % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) or mean (SD) | N (%) or mean (SD) | p | Mean (SD) or CC | p | Mean (SD) or CC | p | Mean (SD) or CC | p | |

| Transitional | 25 | 21 (19.1) | 4 (8.7) | 0.106 | 95.6 (19.4) | 0.600 | 28.8 (6.2) | 0.423 | 39.5 (7.6) | 0.009 |

| Complete | 131 | 89 (80.9) | 42 (91.3) | 98.2 (22.9) | 27.3 (8.8) | 44.5 (8.7) | ||||

| Unbalanced to the RV | 14 | 7 (6.4) | 7 (15.2) | 0.198 | 82.8 (27.7) | 0.030 | 20.9 (11.2) | 0.001 | 43.4 (13.2) | 0.801 |

| Balanced | 133 | 96 (87.3) | 37 (79.6) | 99.2 (21.4) | 27.9 (7.9) | 43.8 (8.4) | ||||

| Unbalanced to the LV | 9 | 7 (6.4) | 2 (4.4) | 100.0 (19.8) | 33.1 (5.4) | 41.9 (5.4) | ||||

| RV/LV inflow angle | 91.4 (18.0) | 85.1 (17.4) | 0.049 | 0.144 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.662 | 0.098 | 0.225 | |

| Preop LAVVR: none/mild | 134 | 93 (84.6) | 41 (89.1) | 0.453 | 98.2 (22.9) | 0.604 | 27.2 (8.7) | 0.136 | 44.4 (8.7) | 0.011 |

| Preop LAVVR: mod/severe | 22 | 17 (15.4) | 5 (10.9) | 95.5 (18.4) | 29.4 (5.7) | 39.3 (7.4) | ||||

The mural leaflet measures were all normally distributed, each with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.86 or greater. Smaller mural leaflet tip angle and leaflet area were both significantly associated with RV-dominant unbalanced AVC, implying a narrower and more pointed mural leaflet when the left ventricle is hypoplastic. Cleft length percentage remained around 40% regardless of ventricular balance. Shorter cleft lengths were associated with transitional AV canal defect. Shorter cleft length was also associated with preoperative, but not postoperative LAVVR. There were no associations with RV/LV inflow angle.

Surgical Characteristics and Post-Surgical Outcomes

No significant associations between papillary muscle configuration and early postoperative LAVVR were found; however, 17% of patients with closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles had moderate or greater long-term LAVVR, compared to 40% of those with widely-spaced papillary muscles (Table 4). Smaller mural leaflet area was also associated with less severe long-term LAVVR. Age at surgery was inversely associated with mural leaflet angle and area.

Table 4.

Surgical characteristics and post-surgical outcomes. CC, correlation coefficient.

| Widely Spaced | Closely Spaced/Asymmetric | Mural Leaflet Tip Angle | Mural Leaflet Area % | Cleft Length % | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) or Median (IQR) | N (%) or Median (IQR) | p | Mean (SD) or CC | p | Mean (SD) or CC | p | Mean (SD) or CC | p | |

| Age at surgery | 110.0 (88, 157) | 114 (84,191) | 0.702 | −0.176 | 0.028 | −0.176 | 0.028 | 0.0004 | 0.996 | |

| Weight at surgery | 4.8 (4.1, 5.4) | 4.7 (4.2, 6.3) | 0.620 | −0.130 | 0.104 | −0.095 | 0.239 | 0.013 | 0.869 | |

| Two-patch | 115 | 80 (73.4) | 35 (76.1) | 0.726 | 97.4 (21.9) | 0.892 | 27.6 (8.7) | 0.838 | 44.1 (8.7) | 0.283 |

| Single patch/Nunn | 40 | 29 (26.6) | 11 (23.9) | 98 (23.7) | 27.3 (7.7) | 42.3 (8.8) | ||||

| No surgical cleft closure | 14 | 9 (8.2) | 5 (10.9) | 0.218 | 89.9 (33.3) | 0.300 | 22.8 (10.8) | 0.052 | 47.1 (9.7) | 0.180 |

| Partial | 26 | 15 (13.6) | 11 (23.9) | 96.6 (25.1) | 26.5 (9.9) | 45 (9.2) | ||||

| Complete | 116 | 86 (78.2) | 30 (65.2) | 99 (20) | 28.3 (7.6) | 43 (8.5) | ||||

| No LAVV reintervention | 140 | 98 (73.4) | 42 (91.3) | 0.678 | 98.1 (22.4) | 0.615 | 27.7 (8.3) | 0.483 | 44.0 (8.6) | 0.206 |

| Reoperation/replacement | 16 | 12 (10.9) | 4 (8.7) | 95.1 (22.1) | 26.1 (9.1) | 41.1 (9.4) | ||||

| Alive | 150 | 107 (97.3) | 43 (93.5) | 0.361 | 98.1 (22.6) | 0.352 | 27.7 (8.5) | 0.188 | 43.6 (8.8) | 0.379 |

| Deceased/transplant | 6 | 3 (2.7) | 3 (6.5) | 89.4 (10.5) | 23.1 (5.4) | 46.8 (5.9) | ||||

| Early LAVVR: none/mild | 98 | 68 (61.8) | 30 (65.2) | 0.689 | 96.8 (22.2) | 0.475 | 26.8 (8.1) | 0.176 | 44.6 (8.4) | 0.150 |

| Early LAVVR: mod/severe | 58 | 42 (38.2) | 16 (34.8) | 99.4 (22.7) | 28.7 (8.9) | 42.4 (9.1) | ||||

| Late LAVVR: none/mild | 63 | 38 (60.3) | 25 (83.3) | 0.026 | 94.9 (25.8) | 0.122 | 26.6 (8.7) | 0.019 | 45.1 (8.7) | 0.162 |

| Late LAVVR: mod/severe | 30 | 25 (39.7) | 5 (16.7) | 103.4 (10.5) | 30.0 (7.4) | 42.4 (8.3) | ||||

When comparing four categories of papillary muscle morphology, asymmetric and double orifice LAVV were associated with the most acute RV/LV inflow angles, and cleft closure was least likely in double orifice LAVV (Supplemental Table). There were no associations with long-term LAVVR.

Risk Factors for Postoperative LAVVR

No significant associations were found between early- or late postoperative LAVVR and sex, AVC type, surgical weight, repair type, or degree of cleft closure. Patients with Trisomy 21 were overrepresented in the group with no significant early LAVVR (Table V). Longer bypass time, deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, and repeat bypass runs were associated with early, but not late, postoperative LAVVR.

Table 5.

Associations between patient characteristics and early versus late LAVVR (> 6 months).

| Early postoperative LAVVR | Late postoperative LAVVR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None/mild (N=98) N (%) or median (IQR) |

Moderate/severe (N=58) N (%) or median (IQR) |

p | None/mild (N=63) N (%) or median (IQR) |

Moderate/severe (N=30) N (%) or median (IQR) |

p | |

| None | 11 (11%) | 20 (35%) | 0.001 | 12 (19%) | 7 (23%) | 0.632 |

| Trisomy 21 | 85 (87%) | 36 (62%) | 51 (81%) | 23 (77%) | ||

| Other | 1 (1%) | 2 (4%) | - | - | - | |

| Bypass time | 59.6 (25, 152) | 73 (27, 166) | 0.022 | 59.02 (25, 166) | 69.23 (27, 152) | 0.127 |

| Cross-clamp time | 45.9 (19, 116) | 51.6 (22, 134) | 0.153 | 44.89 (19, 115) | 50.93 (21, 116) | 0.196 |

| Use of circulatory arrest | 0 (0%) | 6 (10%) | 0.002 | 2 (3%) | 1 (3%) | 1.000 |

| >1 bypass run | 5 (5%) | 11 (19%) | 0.006 | 2 (3%) | 3 (10%) | 0.324 |

| No reoperation | 96 (98%) | 44 (76%) | <0.001 | 62 (98%) | 25 (83%) | 0.006 |

| LAVV Reoperation | 2 (2%) | 14 (24%) | 1 (2%) | 5 (17%) | ||

| Preoperative LAVVR: None/mild | 88 (90%) | 46 (79%) | 0.069 | 57 (90%) | 24 (80%) | 0.159 |

| Preoperative LAVVR: Mod/severe | 10 (10%) | 12 (21%) | 6 (10%) | 6 (20%) | ||

| None/mild early postoperative LAVVR | 50 (79%) | 10 (33%) | <0.001 | |||

| Mod/severe early postoperative LAVVR | 13 (21%) | 20 (67%) | ||||

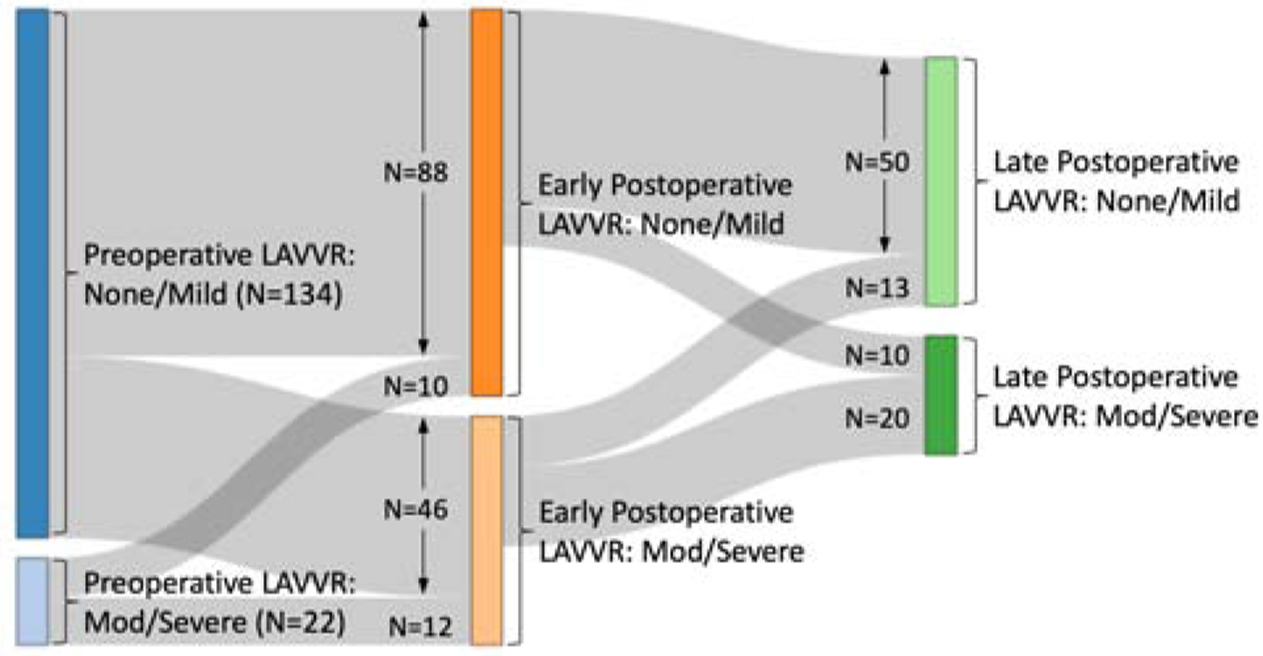

Of those with significant early postoperative LAVVR, 24% required reintervention, compared to 2% in those with mild or less early LAVVR (Table 5). Of those with significant late LAVVR, 17% underwent reintervention during the study period. Early postoperative LAVVR was associated with significant late LAVVR, although a third of patients who had significant late LAVVR had mild or less early LAVVR (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Diagram depicting pre- and postoperative LAVVR over time in the study cohort.

No patients had severe LAVV stenosis or required reintervention for stenosis.

Multivariable Models

In multivariable analyses (Table 6), controlling for weight at surgery, genetic syndromes and bypass time, papillary muscle morphology (Model 1) and mural leaflet area percentage (Model 2) were not associated with early LAVVR. However, the presence of widely spaced papillary muscles increased the odds ratio for late LAVVR to 3.6 (Model 1, p=0.026). In Model 2, each percentage increase in mural leaflet area was associated with an increased odds ratio of 1.07 for late LAVVR (p=0.023).

Table 6.

Multivariable models. Both models include weight at surgery, presence or absence of genetic syndrome, and bypass time.

| Early LAVVR | Late LAVVR | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |

| Model 2, mural leaflet area | 1.03 | 0.988–1.074 | 0.167 | 1.074 | 1.010–1.142 | 0.023 |

Comment

The persistent challenge of achieving durable LAVV competence after AVC repair may be rooted in the anatomic diversity of the valvar and subvalvar architecture. The left mural leaflet has not been well characterized in the literature. We sought to describe left mural leaflet morphology and papillary muscle arrangement in AVC by standard two-dimensional echocardiography, and investigate them as risk factors for early or late postoperative LAVVR.

We found that papillary muscle morphology and mural leaflet characteristics are closely associated with each other and various anatomic factors. RV/LV inflow angles are more acute in patients with closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles. While RV/LV angle has been suggested as a proxy for VSD size [14], the difference between groups in our study did not reach the acuity previously shown to predict severe postoperative LAVVR (≤59˚) [11].

Mural leaflet morphology was not uniform across AVC subtypes. In RV-dominant unbalanced AVC, mural leaflets were smaller and more acute. Accordingly, there was an inverse relationship between age at surgery and mural leaflet area and angle, as patients with right-dominant AVC would be more likely to require arch repair and PA band placement, delaying complete repair. Patients with smaller mural leaflet area were less likely to undergo cleft closure (routinely performed during AVC repair at our institution), likely because the surgeon sought to avoid LAVV stenosis. Given the previously demonstrated association between cleft closure and decreased LAVVR [15], we expected smaller mural leaflet area to be associated with postoperative LAVVR. However, there was no association with early LAVVR. In fact, smaller mural leaflet was associated with decreased prevalence of significant long-term LAVVR. This counterintuitive finding may be because the two-dimensional area, measured when the valve is closed, does not capture the coapting surface and thus cannot differentiate between mural leaflets with more versus less robust coaptation.

Smaller mural leaflet measures were associated with closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles. Consequently, it was not surprising that fewer patients with closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles had significant long-term LAVVR compared to those with widely-spaced papillary muscles in both univariable and multivariable analyses. Papillary muscles are difficult to characterize in a quantifiable way on standard two-dimensional preoperative echocardiograms, and so we had hoped the mural leaflet measures would serve as proxies. However, the difference in mural leaflet size of 3.4% between groups was not clinically applicable. Therefore, papillary muscle structure, rather than leaflet morphology, may be the more meaningful anatomic risk factor for late LAVVR.

Others have evaluated left AV valve morphology in the setting of AVC. Ando et al. found valvar malformations such as papillary muscle abnormalities with a hypoplastic mural leaflet, and double-orifice LAVV, increased the risk of postoperative LAVVR [5]. In contrast, Takahashi et al. noted that severity of postoperative LAVVR was related to lateral displacement of the anterolateral papillary muscle, or more widely-spaced papillary muscles [7]. Our findings are consistent with the Takahashi study.

A study of postmortem AVC specimens by Kanani et al. suggests an explanation. They surmised that there must be a lateral component to the contractile forces of the papillary muscles in AVC such that the superior and inferior bridging leaflets are pulled away from each other with each heartbeat. Over the long term, these stress forces from the subvalvar apparatus may lead to separation of even initially competent, surgically-joined superior and inferior bridging leaflets [16]. Closely-spaced papillary muscles, however, may exert less lateral force on the cleft and achieve more durable competence.

In our cohort, two-thirds of patients who required reintervention for LAVVR underwent surgery within 80 days. Indicators of increased surgical complexity such as longer bypass time, use of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, and additional bypass runs were associated with early, but not late, postoperative LAVVR. There is no standardized practice for reinstituting bypass at our institution, allowing each surgeon to balance feasibility of further repair and the risk of stenosis in each patient. One third of patients with significant long-term LAVVR had mild or less LAVVR in the immediate postoperative period (Figure 3). Papillary morphology is associated with late but not early LAVVR, thus suggesting that the mechanisms of late postoperative LAVVR differ from early postoperative LAVVR. Annular remodeling [13], ventricular remodeling, and cumulative stress forces [16] have been proposed as contributors to late LAVVR. Our study suggests closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles may be a protective anatomic factor in the long term.

Our study did not reveal any new demographic risk factors for significant early or long-term postoperative LAVVR. Significant early postoperative LAVVR was associated with increased significant long-term LAVVR, as has been previously reported [2].

This is one of few studies to examine papillary morphology, and the first to assess the role of left mural leaflet morphology in both short-term and long-term LAVVR after AVC repair. Limitations of this study include its retrospective, single-center design. Follow-up echocardiograms six months or more following surgery were available in 60% of the study cohort due to proximity of surgical date to the end of our study period and follow-up care outside our institution. Our surgical approach favors a two-patch technique with cleft closure when possible, and thus we cannot comment on other surgical techniques. Some centers have suggested that a modified single-patch technique may decrease the risk of LAVV reintervention [17], however a Pediatric Health Network multicenter observational study found that LAVVR outcomes did not differ by repair type [2]. There were no instances of significant LAVV stenosis in our cohort, which suggests a surgical preference for leaving regurgitation when there is concern about LAVV size. As a result, we could not evaluate the relationship between our papillary and mural leaflet measures and postoperative LAVV stenosis. Due to the limitations of standard two-dimensional echocardiography, the mechanism of postoperative LAVVR could not be accurately assessed. Lastly, this study did not evaluate the impact of LAVV morphology in single ventricle palliation.

In summary, closely-spaced or asymmetric papillary muscles may be a protective anatomic factor in AVC surgery as they are associated with decreased significant long-term postoperative LAVVR. Our findings support disparate risk factors for long-term versus immediate postoperative LAVVR. Mild early postoperative LAVVR does not preclude development of significant late LAVVR, which underscores the importance of continued postoperative follow-up. Future study of papillary muscle architecture in AVC with advanced imaging methods is needed to elucidate the role of the papillary muscles in long-term postoperative LAVVR.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Meeting Presentation: Portions of this study were presented at the American Society of Echocardiography Scientific Sessions, Nashville, TN, June 22–26, 2018.

References

- [1].Alsoufi B, Al-Halees Z, Khouqeer F, Canver CC, Siblini G, Saad E, et al. Results of left atrioventricular valve reoperations following previous repair of atrioventricular septal defects. J Card Surg 2010;25:74–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Atz AM, Hawkins JA, Lu M, Cohen MS, Colan SD, Jaggers J, et al. Surgical management of complete atrioventricular septal defect: Associations with surgical technique, age, and trisomy 21. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011;141:1371–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Ten Harkel ADJ, Cromme-Dijkhuis AH, Heinerman BCC, Hop WC, Bogers AJJC. Development of left atrioventricular valve regurgitation after correction of atrioventricular septal defect. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:607–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Adachi I, Uemura H, McCarthy KP, Ho SY. Surgical anatomy of atrioventricular septal defect. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2008;16:497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ando M, Takahashi Y. Variations of Atrioventricular Septal Defects Predisposing to Regurgitation and Stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:614–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Prifti E, Bonacchi M, Baboci A, Giunti G, Krakulli K, Vanini V. Surgical outcome of reoperation due to left atrioventricular valve regurgitation after previous correction of complete atrioventricular septal defect. J Card Surg 2013;28:756–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Takahashi K, MacKie AS, Thompson R, Al-Naami G, Inage A, Rebeyka IM, et al. Quantitative real-time three-dimensional echocardiography provides new insight into the mechanisms of mitral valve regurgitation post-repair of atrioventricular septal defect. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2012;25:1231–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cohen MS, Jegatheeswaran A, Baffa JM, Gremmels DB, Overman DM, Caldarone CA, et al. Echocardiographic features defining right dominant unbalanced atrioventricular septal defect: A multiinstitutional congenital heart surgeons’ society study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:508–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cohen MS, Spray TL. Surgical management of unbalanced atrioventricular canal defect. Pediatr Card Surg Annu 2005;8:135–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Cohen MS, Jacobs ML, Weinberg PM, Rychik J. Morphometric analysis of unbalanced common atrioventricular canal using two-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;28:1017–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Bharucha T, Sivaprakasam MC, Haw MP, Anderson RH, Vettukattil JJ. The Angle of the Components of the Common Atrioventricular Valve Predicts the Outcome of Surgical Correction in Patients With Atrioventricular Septal Defect and Common Atrioventricular Junction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2008;21:1099–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Szwast AL, Marino BS, Rychik J, Gaynor JW, Spray TL, Cohen MS. Usefulness of left ventricular inflow index to predict successful biventricular repair in right-dominant unbalanced atrioventricular canal. Am J Cardiol 2011;107:103–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kaza E, Marx GR, Kaza AK, Colan SD, Loyola H, Perrin DP, et al. Changes in left atrioventricular valve geometry after surgical repair of complete atrioventricular canal. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;143:1117–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jegatheeswaran A, Pizarro C, Caldarone CA, Cohen MS, Baffa JM, Gremmels DB, et al. Echocardiographic definition and surgical decision-making in unbalanced atrioventricular septal defect: A congenital heart surgeons’ society multiinstitutional study. Circulation 2010;122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Boening A, Scheewe J, Heine K, Hedderich J, Regensburger D, Kramer H-H, et al. Long-term results after surgical correction of atrioventricular septal defects. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg 2002;22:167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kanani M, Elliott M, Cook A, Juraszek A, Devine W, Anderson RH. Late incompetence of the left atrioventricular valve after repair of atrioventricular septal defects: The morphologic perspective. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:640–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Backer CL, Stewart RD, Mavroudis C. What Is the Best Technique for Repair of Complete Atrioventricular Canal? Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;19:249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.