Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the impact of a Social Branding intervention in bars and nightclubs on smoking behavior.

Design:

Quasi-experimental controlled study.

Setting:

Bars and nightclubs in San Diego and San Francisco (intervention) and Los Angeles (control).

Participants:

“Hipster” young adults (age 18–26) attending bars and nightclubs.

Intervention:

Anti-tobacco messages delivered through monthly anti-tobacco music/social events, opinion leaders, original art, direct mail, promotional activities, and online media.

Measures:

A total of 7240 surveys were collected in 3 cities using randomized time location sampling at baseline (2012–2013) and follow-up (2015–2016); data were analyzed in 2018. The primary outcome was current smoking.

Analysis:

Multivariable logistic regression assessed correlates of smoking, adjusting for covariates including electronic cigarette use; differences between cities were evaluated using location-by-time interactions.

Results:

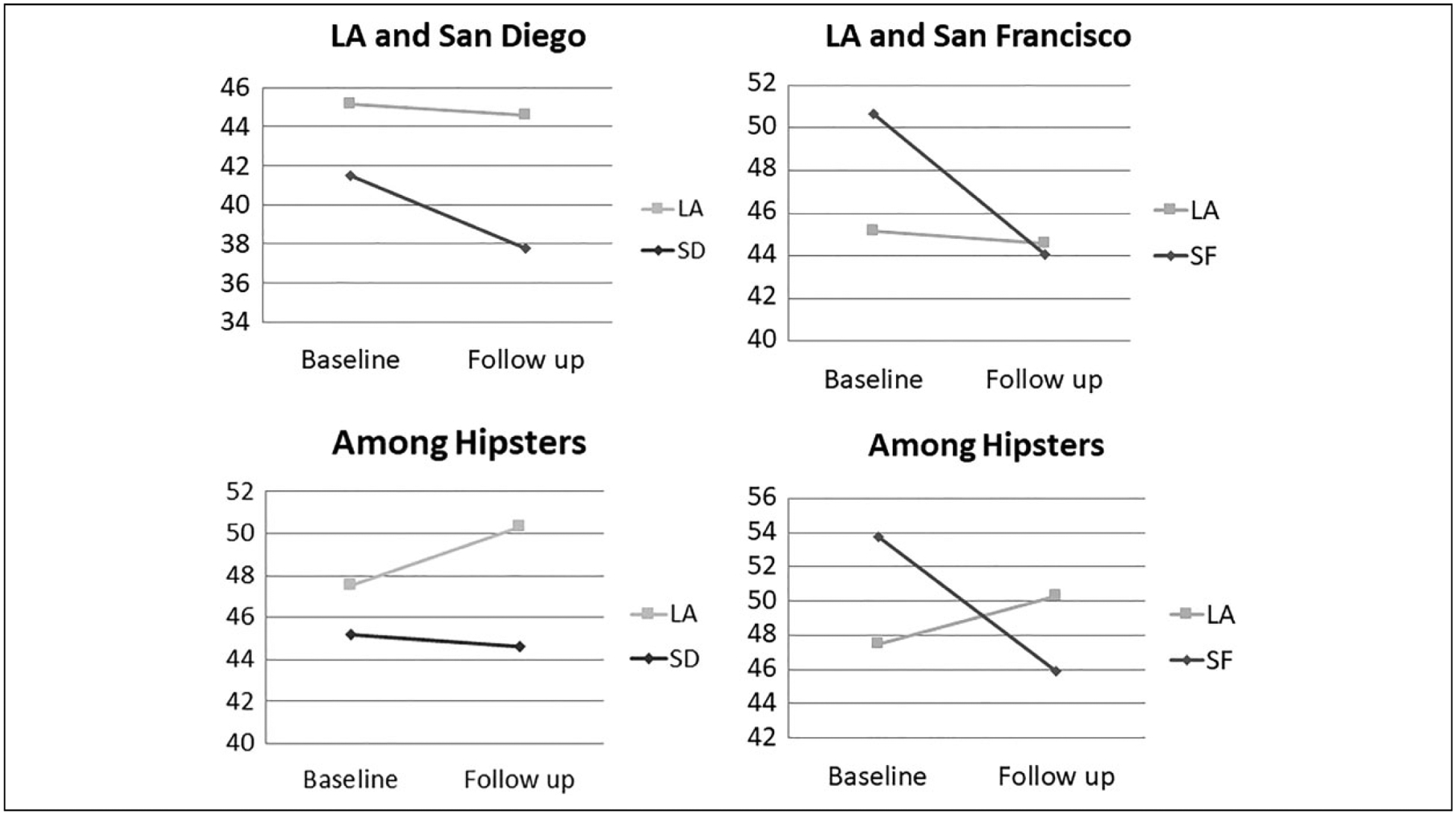

Smoking in San Francisco decreased at a significantly faster rate (51.1%−44.1%) than Los Angeles (45.2%−44.5%) (P = .034). Smoking in San Diego (mean: 39.6%) was significantly lower than Los Angeles (44.8%, P < .001) at both time points with no difference in rate of change. Brand recall was not associated with smoking behavior, but recall was associated with anti-tobacco attitudes that were associated with smoking.

Conclusion:

This is the first controlled study of Social Branding interventions. Intervention implementation was accompanied by decreases in smoking (San Francisco) and sustained lower smoking (San Diego) among young adult bar patrons over 3 years.

Keywords: smoking, young adult, prevention, bars

Purpose

Young adults have high rates of tobacco use,1 and most experimenters either quit or progress to regular smoking during young adulthood.2 Young adult smoking cessation is important, as quitting smoking before the age of 30 avoids most of its long-term health consequences.3–5 Tobacco industry marketing targets young adults6 using sophisticated psychographic targeting to align cigarette brand images with the values of different social groups.7 Young adult bar patrons have high smoking rates,8 and tobacco companies used promotional activities in bars to increase the social acceptability of smoking.9 These promotions also reinforce links between smoking and alcohol consumption, which may enhance nicotine addiction.10 Tobacco companies have also used trendsetters to transmit marketing messages in bars, sometimes without bar patrons’ knowledge.7,11–13

Social Branding utilizes psychographic targeting similar to tailored tobacco marketing to influence the social norms and value systems within groups called “peer crowds.”14–16 Unlike an individual’s peer group of friends, the peer crowd includes a larger group of people who, while personally unknown to the individual, share a common set of values, motivations, activities, personal style, and social communication channels (eg, hipsters, partiers, hip-hop, or country).15,16 Peer crowd affiliation is significantly associated with tobacco use and other risk behaviors.17 Social Branding targets by peer crowd and incorporates commercial branding and promotion strategies to promote a tobacco-free brand that competes with tobacco brands.15,16 The Social Brand is an organizing and unifying force, aligning influencers, events, and media to drive norm and attitude change.15,18,19 Influencers disseminate campaign messaging, adding authenticity to the brand and reaching smokers in a cost-efficient manner.18–20

Social Brands have been developed for bar interventions targeting hipsters in San Diego,15 partiers in Oklahoma City21 and Albuquerque,22 and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young adults in Las Vegas.23 Social Branding anti-tobacco media campaigns for teens include the Food and Drug Administration’s Fresh Empire19 (hip-hop) campaign, and the Virginia Foundation for Healthy Youth’s Down and Dirty18 (country) campaign. Social Branding interventions in bars were associated with decreased smoking in 4 uncontrolled studies, and brand recall and understanding have been associated with greater decreases in smoking.15,21–23 This article presents the first controlled study of a Social Branding intervention. We studied 1 city with an intervention running between 2008 and 2016 (San Diego), 1 city (San Francisco) replicating the intervention between 2013 and 2016, and 1 comparison community (Los Angeles). The primary hypothesis (H1) was that current smoking would decrease in intervention cities compared to the control. Secondary hypotheses were (S1) that among Hipster young adults, decreases in smoking would be greater in intervention cities and that intervention exposure would be associated with (S2) decreased smoking behavior and (S3) decreased social acceptability of smoking and anti-tobacco industry attitudes. Finally, we hypothesized (S4) that similar to prior studies,15,21,24,25 perceived smoking social acceptability and anti-industry attitudes would be associated with smoking.

Methods

Intervention and Study Design and Setting

The intervention has been described in detail elsewhere.15 Similar to iconic commercial brands (where Nike stands for American authentic athletic performance), a Social Brand is created for the campaign and positioned with an image that resonates with the core values of the peer crowd target audience and connects authentic peer crowd membership with reasons to be tobacco free. In this case, in formative research, hipsters were found to favor alternative rock music, creativity and self-expression, artistic personal style, and were more engaged with social causes. The hipster anti-tobacco brand, Commune, was launched in an intervention in San Diego in 2008 and Figure 1 includes examples of the logos, flyers and posters from the intervention.15 Extensive formative research supported the Commune brand positioning as “a movement of artists, designers and musicians that take a stand against tobacco corporations and their presence in the art and music scene.” The intervention included several components to deliver anti-tobacco messages, including branded events; influencers delivering anti-tobacco messages through original artwork, in personal profiles, or during live performances; social rewards for nonsmokers; and smoking cessation groups that were created for social leaders. As authentic membership in the Hipster community was important to this peer crowd, the initial events established authenticity in the community prior to the start of anti-tobacco messaging, and local young artists were hired to create the anti-tobacco campaign materials such as posters or t-shirts based on facts that inspired them. The events were promoted using social media, direct mail, and paid advertising. The intervention was associated with a significant decrease in smoking in San Diego over the first 4 years,15 and it continued from 2012 to 2016 for this study. The Commune brand was updated in 2012 for San Francisco. The San Francisco core message and positioning was identical; new local artists and community partners were recruited, and the logo and website were updated to reflect local design aesthetics (Figure 1). While the San Francisco market is larger than San Diego, annual funding was similar, so the intervention emphasized local influencers to cause change. These influencers included artists, musicians, fashion designers, bartenders, and others with strong local hipster networks. Influencers created anti-tobacco art/clothing, working, or performed at Commune events highlighting anti-tobacco messages.

Figure 1.

Examples of commune branded promotional materials and art updated for implementation in San Francisco.

We collected surveys between 2012 and 2016 in the 3 cities using randomized samples of young adults attending Hipster bars. As in prior evaluations, venues, dates, and times were selected randomly using time–location sampling,26,27 which effectively engages hard-to-reach populations. We created a census of popular Hipster bars using focus groups and interviews with key informants in each community (eg, local bartenders, promoters, musicians) and randomly selected venues, dates, and times for data collection. Data collection did not occur during Commune events, but venues that hosted Commune events were included in the census. During the selected date and time, trained personnel approached individuals in the venue who appeared to be under 30 years old for screening; eligible participants were age 18 to 26, lived in the area, had not previously completed a survey, and did not appear to be intoxicated. Participants completed a paper questionnaire that included demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, exposure to Commune, and attitudes about tobacco. Participants gave verbal informed consent and received $5 compensation. The study protocol was approved by the Committee for Human Research (the institutional review board) at the University of California San Francisco.

Consistent with the size of multiple pilot studies, we collected approximately 1200 surveys at “baseline” (2012–2013) in each of the 3 cities (prior to intervention in San Francisco and at year 4 in San Diego) and 1200 surveys at “follow-up” (2015–2016) in each city, reflecting full intervention implementation in San Francisco and sustained implementation in San Diego. Los Angeles was selected as the comparison community with similar young adult demographics and the same smoke-free bar policies. Data were analyzed in 2018.

Measures

Outcome: Current smoking status.

Participants reported the number of days in the past 30 days they used cigarettes. This variable was recoded into 3 categories: nonsmokers (0 days of smoking), nondaily smokers (1–29 days), and daily smokers (30 days), and dichotomizedintosmokers and nonsmokersfor the main analysis.

Demographics.

We created a continuous variable based on date of data collection and date of birth, excluding those outside the 18–26 year age range. Other demographic variables included sex (dichotomized male/female) and education (3 levels: in college/graduated from college/dropped out of college or completed high school or general equivalency diploma). Race was asked differently at baseline and follow-up. At baseline, participants were asked 2 questions, “Are you Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin?” and to select race (African American/Asian/White/Hawaiian or Pacific Islander/American Indian or Alaskan Native/more than one race). At follow-up, the questionnaire was unchanged, but respondents had the option of choosing more than one race. All respondents were recoded into 5 groups (Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic other).

Peer crowd affiliation.

We used the I-Base survey identically to multiple past studies described elsewhere.14,16,17,28 Briefly, participants selected photos of young adults they perceived to be most and least like their friends; photo selections yielded scores for each peer crowd (eg, hipster, partier, hip-hop, young professional, country, homebody), and participants’ main affiliation with a peer crowd was based on the highest score.

Other product use.

Electronic cigarette use was assessed similarly to cigarettes. Participants consuming at least 4 (for women) or 5 (for men) alcoholic shots or drinks within a few hours in the past month were coded dichotomously as binge drinkers.

Brand recall.

Individuals reported if they had heard of “Commune” or “Commune Wednesdays,” had been to a Commune event, or had visited Commune’s Facebook page or website.

Antismoking trends.

Participants were asked, “What are trends in tobacco smoking that you have seen in the past year?” and rated 4 items: “In the places I party, people are smoking tobacco” (reverse coded), “In the places I party, smoking is accepted” (reverse coded), “People I party with are trying tostopsmoking”, and “I can relate to reasons not to smoke cigarettes.” Answers were on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = a lot less, 2 = less, 3 = about the same, 4 = more, 5 = a lot more); we computed the mean across the 4 items. Anti-industry attitudes were calculated as the mean of 3 items used in prior studies,24,25 measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

To address social desirability bias, surveys were collected at randomly selected times and places, not during intervention activities. Data were analyzed and interpreted independent of intervention implementation.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive characteristics were calculated for each city by time point. Multivariable logistic regression assessed correlates of current smoking. Models were tested first unadjusted, and second adjusting for demographic covariates. Since the intervention took place while electronic cigarettes were widely adopted and advertised as smoking cessation aids, we conducted a third set of analyses adding electronic cigarette use to the models. Differences between the intervention and comparison cities on smoking (H1) were evaluated using a location-by-time interaction effect. San Francisco and San Diego were compared to Los Angeles in separate models. As the intervention targeted Hipsters, a secondary analysis repeated models among the Hipster subgroup. Similar to the main analysis, we hypothesized (S1) that among Hipsters, current smoking would decrease in intervention cities more than the control, indicated by a significant location-by-time interaction.

In addition, we ran exploratory regressions to examine associations between brand recall, antismoking trends, anti-industry attitudes, and smoking. We hypothesized (S2) that brand recall would be associated with smoking status. We also ran linear regressions using Commune brand recall as the independent variable and perceived antismoking trends and anti-industry attitudes as outcomes, to test the hypothesis (S3) that Commune brand recall would be significantly associated with these factors. Finally, we ran logistic regressions with perceived antismoking trends and anti-industry attitudes as independent variables and current smoking as the outcome, hypothesizing (S4) that these attitudes would be associated with smoking status. Analyses were completed using SAS software version 9.429 with α set at .05.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In the overall sample (all locations and time points combined), 3025 (44%) participants were smokers (32.6% nondaily and 11.4% daily); the mean age was 23.97 (SD = 1.8); 46.9% (N = 3334) were female. Most had graduated from college (n = 3022, 42.4%) or were currently attending college (n = 2701, 37.9%). The sample was diverse; 38.9% (n = 2781) were non-Hispanic white, 36.7% (n = 2622) were Hispanic, 11.0% (n = 3925) were Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander, 8.3% (n = 594) were non-Hispanic other, and 5.0% (n = 355) were non-Hispanic black; demographics by city and time are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics by Location and Time of Study.a

| Los Angeles | San Diego | San Francisco | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | Baseline (n = 1143) | Follow-Up (n = 1291) | Baseline (n = 1209) | Follow-Up (n = 1193) | Baseline (n = 1211) | Follow-Up (n = 1193) |

| Age, M (SD) | 23.49 (2.07) | 23.53 (2.15) | 24.26 (1.61) | 24.20 (1.72) | 24.04 (1.61) | 24.29 (1.65) |

| Female, n (%) | 537 (47.1%) | 606 (48.6%) | 600 (49.8%) | 535 (43.4%) | 536 (44.6%) | 520 (44.7%) |

| Education, n (%) | ||||||

| Graduated from college | 402 (35.3%) | 431 (34.7%) | 506 (41.9%) | 515 (44.3%) | 569 (47.0%) | 599 (51.3%) |

| In college | 512 (45.0%) | 536 (43.2%) | 453 (37.5%) | 399 (34.3%) | 409 (33.8%) | 392 (33.6%) |

| Drop out of college/HS/GED | 224 (19.7%) | 274 (22.1%) | 248 (20.6%) | 248 (21.4%) | 232 (19.2%) | 177 (15.1%) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Black | 53 (4.6%) | 122 (9.8%) | 36 (3.0%) | 28 (2.4%) | 61 (5.1%) | 55 (45.6%) |

| API | 114 (10.0%) | 109 (8.7%) | 111 (9.2%) | 143 (12.2%) | 165 (13.7%) | 147 (12.5%) |

| Other | 63 (5.5%) | 84 (6.7%) | 92 (7.7%) | 123 (10.5%) | 90 (7.5%) | 142 (12.1%) |

| Hispanic | 536 (47.0%) | 532 (42.6%) | 466 (38.8%) | 520 (44.3%) | 269 (22.3%) | 299 (25.5%) |

| White | 375 (32.9%) | 401 (32.2%) | 497 (41.3%) | 359 (30.6%) | 620 (51.4%) | 529 (45.2%) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||||

| Nondaily (1–29 days) | 368 (33.4%) | 385 (32.5%) | 353 (30.0%) | 317 (27.5%) | 434 (38.1%) | 383 (34.0%) |

| Daily (30 days) | 129 (11.7%) | 143 (12.0%) | 134 (11.4%) | 119 (10.3%) | 147 (12.9%) | 113 (10.0%) |

| Nonsmoker (0 days) | 603 (54.8%) | 658 (55.5%) | 690 (58.6%) | 718 (62.2%) | 557 (48.0%) | 629 (55.0%) |

| E-cigarette user, n (%) | 199 (24.9%) | 305 (26.8%) | 131 (17.3%) | 171 (15.5%) | 84 (12.6%) | 239 (22.4%) |

| Binge alcohol, n (%) | 624 (57.3%) | 777 (68.7%) | 876 (75.3%) | 823 (74.5%) | 889 (78.2%) | 889 (83.2%) |

| Anti-industry, M (SD) | 2.35 (1.20) | 2.63 (1.24) | 2.52 (1.25) | 2.72 (1.27) | 2.47 (1.24) | 2.72 (1.19) |

| Antismoking trends, M (SD) | 3.03 (0.56) | 3.03 (0.57) | 2.94 (0.64) | 3.17 (0.66) | 3.00 (0.58) | 3.21 (0.66) |

Abbreviations: GED, general equivalency diploma; HS, high school; M, mean; SD, standard deviation.

For trend, higher means less smoking.

Electronic cigarette use was more frequent in the Los Angeles sample (25%−27%) and consistently higher than in San Diego (17%−16%). Electronic cigarette use increased in San Francisco between baseline and follow-up (13%−22%). Binge drinking was least frequent in San Diego and most frequent in San Francisco. Anti-industry attitudes increased in all sites, whereas perceived antismoking trends increased in San Diego and San Francisco but not Los Angeles.

Logistic Regression Analysis: Full Sample (H1)

San Francisco compared to Los Angeles.

Current smoking in San Francisco decreased 13.7% and at a faster rate from baseline (51.1%) to follow-up (44.1%) than it did in Los Angeles (baseline = 45.2%, follow-up = 44.5%); the interaction term indicated a significant difference between the 2 cities (β = −.063, P = .034) (Figure 2). Models adjusting for age, sex, education, and race/ethnicity indicated the results were robust (β = −.062, P = .047). In a third model adding electronic cigarette use as a covariate, the interaction remained significant (β = −.81, P = .012). To unpack the location-by-time interaction, we did tests of effect slices. When looking at location within time in the unadjusted and adjusted models, we found a significant effect of location at baseline, with significantly greater smoking in San Francisco compared to Los Angeles (odds ratio [OR] = 1.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.08–1.49; adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.07–1.51); smoking decreased in San Francisco so there was no significant effect of location at follow-up (OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.83–1.16; AOR = 0.99, 95% CI = 0.83–1.18).

Figure 2.

Current smoking prevalence at baseline and follow-up. The smoking rate in San Diego was significantly lower than Los Angeles, but the rate of smoking decline was not significantly different (left); there was a significantly greater rate of decline in smoking in San Francisco compared to Los Angeles (right).

San Diego compared to Los Angeles.

In both the unadjusted and adjusted models, the interaction effect was not statistically significant (Ps > .05; Figure 2). However, in both the unadjusted (β = −.109, P < .001) and adjusted (β = −.116, P < .001) models, there was a significant effect of location suggesting a consistent significant difference between the 2 cities. The mean smoking percentage in San Diego was 39.6% and 44.8% in Los Angeles. When additionally controlling for electronic cigarette use, the effect of location remained significant (β = −.08, P = .012). Therefore, the main hypothesis was supported for San Francisco, but not for San Diego, although smoking remained significantly lower in San Diego than the control (Figure 2).

Logistic Regression Analysis: Hipster Subsample (S1)

San Francisco Compared to Los Angeles.

In the subgroup analysis limited to hipsters, we found that smoking rates decreased in San Francisco between baseline (53.9%) and follow-up (45.9%) compared to Los Angeles (baseline follow-up = 47.5%, follow-up = 50.3%), and the interaction term was significant (β = .11, P = .018; Figure 2). Models adjusting for demographics indicated the results were robust (β = .113, P = .0174). When adding electronic cigarette use as a covariate, the interaction remained significant (β = .166, P = .0041). We did similar tests of effect slices for both the unadjusted and adjusted models; we found there was significantly greater odds of smoking in San Francisco at baseline (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.05–1.59; AOR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.02–1.57), decreasing over time so there was no significant effect of location at follow-up (OR = 0.84, 95% CI = 0.63–1.12; AOR = 0.80, % CI = 0.59–1.10).

San Diego Compared to Los Angeles.

In both unadjusted and adjusted models, the effect of location was significant (β = −.109, P < .001; β = −.116, P < .001), but time and the interaction effect were not statistically significant (Ps > .05). When controlling for electronic cigarette use, the effect of location was still significant (β = −.088, P = .0199).

Therefore, among Hipsters, similar to the findings in the full sample, smoking decreased in San Francisco and remained significantly lower in San Diego. Additionally, in San Francisco, there was a higher baseline rate and a larger decrease in smoking among Hipsters than the full sample.

Testing for Possible Explanatory Variables (S2-S4)

Data from both intervention cities at follow-up were combined to examine potential explanatory variables for the relationship between intervention exposure and smoking behavior. First, we found that brand recall was not related to smoking status (P > .05), so secondary hypothesis S2 was not supported. However, linear regression analysis found that brand recall was related to perceiving antismoking trends (β = −.13, standardized β = −.07, P = .002,), but not to anti-industry attitudes (β = −.039, standardized β = −.01, P = .6786), indicating partial support for secondary hypothesis S3. Logistic regression analysis found that perceived antismoking trends (OR = 0.57, 95% CI = 0.50–0.65) and stronger and anti-industry attitudes (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.64–0.77) were negatively associated with smoking, indicating secondary hypothesis S4 was supported. Perceived antismoking trends were still negatively associated with current smoking when controlling for recall (OR = 0.58, 95% CI = 0.51–0.67), as were anti-industry attitudes (OR = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.63–0.77).

Discussion

This is the first controlled evaluation of Social Branding interventions in bars and nightclubs targeting young adults. We found a significant decrease in smoking in San Francisco but not in the comparison community. We also found that in San Diego, where the intervention had been running for 4 years prior to the controlled study, the smoking rates did not decline at a faster rate, but they remained significantly lower than the comparison community. One explanation for these findings could be that the Commune intervention decreased smoking during its first years of implementation15 and that continuing the intervention sustained lower smoking rates. However, the data are not completely consistent with attributing the observed changes in smoking to the Commune intervention. First, the rates of brand recall and exposure were low, particularly in San Francisco, where rates were lower than in the comparison community and did not increase. Higher recall in Los Angeles may have been affected by a popular local clothing brand also called Commune. In addition, the implementation budget in San Francisco was similar to San Diego, despite its larger population, which might explain lower recall levels. Another explanation for low recall might be that the intervention was designed to act through the social networks of influencers rather than campaign messaging alone, so smoking behavior may have changed despite low brand recall rates. In fact, the San Francisco intervention relied more on local influencers, officially engaging over 200 Hipster influencers with Commune. Unfortunately, standard evaluation models emphasize brand recall, which requires large media budgets. A social network analysis might be useful to capture these effects, but it is cost prohibitive to conduct throughout a large city. Innovations in evaluation are needed to better measure effects of marketing interventions that do not emphasize mass media like Social Branding.

An alternative explanation is that the differences in smoking in San Francisco were due to electronic cigarette use. The time period of the intervention corresponds to aggressive promotion and uptake of electronic cigarettes nationally,30 and we observed a large increase in electronic cigarette use between baseline and follow-up in San Francisco. However, if electronic cigarettes accounted for decreased smoking, we would expect for higher or increasing rates of electronic cigarette use to be associated with less smoking; instead rates of both electronic cigarette use and smoking were higher in Los Angeles than San Diego. To address this issue more directly, we added electronic cigarette use as a covariate in the models and found the interactions and associations did not change, suggesting the effect was not attributable to electronic cigarette use. This finding is consistent with longitudinal studies of young adults showing electronic cigarette use predicts future cigarette smoking31 and greater frequency and quantity of cigarette use.32 While one study reported electronic cigarette use specifically to quit smoking was associated with increased odds of cessation, electronic cigarette use for other reasons was not,33 and young adult bar patrons may be less likely to use electronic cigarettes specifically to quit smoking.

Due to low brand recall, it is difficult to assess the relationship between intervention exposure and smoking behavior. We did not find an association between brand recall and current smoking, although we found that brand recall was related to perceptions of decreased popularity of smoking and increased smoking cessation trends, and these attitudes were also significantly associated with smoking behavior. As shown in the descriptive results (Table 1), these attitudes increased in both intervention cities, but not in the control community. It is possible that Social Branding affects smoking norms, which in turn influence behavior. The Social Brand also frequently included anti-tobacco industry messaging, as local artists frequently chose to incorporate anti-tobacco industry themes into their posters and other intervention communications. Prior research has shown a strong relationship between support for action against the tobacco industry and smoking behavior, as well as intention to quit among smokers.24,25 We found the anti-industry attitudes were related to smoking behavior, but not to brand recall. This effect might be observed if anti-tobacco industry attitudes spread from Commune influencers who were perceived as peers rather than brand ambassadors. Anti-industry attitudes also increased in both the intervention and control communities, suggesting that Commune messaging might benefit from a stronger connection to support for action against the tobacco industry. Longitudinal studies and qualitative research would be helpful to understand potential relationships between Social Branding interventions, messaging, perceptions, and smoking.

Strengths and Limitations

This study adds substantially to prior evaluations of Social Branding, which did not include comparison communities, so we are more confident that the changes observed were not secular effects. All cities were in large urban areas in California, which provided a consistent policy context (such as smoke-free bar policies). While this limits the generalizability of the study, it enhances the validity of comparisons between the intervention and control cities. The use of time location sampling to access a randomized sample of young adult Hipster bar patrons is also a strength, as the study population is more likely to reflect the behavior in the broader population of young adult Hipster bar patrons than a convenience sample linked to intervention activities. The sociodemographic consistency of the randomized samples at baseline and follow-up also suggests that time location sampling yields comparable samples. The study relied on self-reported smoking data without biological validation, although numerous prior studies have demonstrated the reliability of self-reported smoking status. Finally, this intervention focused on cigarette smoking. While we found that electronic cigarette use did not change the results when included in the models as a covariate, the study did not address electronic cigarette and alternative product use as outcomes. As use of alternative tobacco products is increasing, particularly among young adults, there is a need to address these tobacco products in addition to cigarette smoking. However, as most users of multiple tobacco products smoke cigarettes,1 interventions to address cigarette smoking are still relevant.

Conclusions

Social Branding is a feasible and acceptable intervention appealing to high-risk young adults. In cities with the Commune intervention, smoking rates declined or remained lower than in the comparison community, controlling for sociodemographics and electronic cigarette use. Social Branding appears to be an effective strategy to reduce smoking in a high-risk and hard-to-reach population. Future interventions may benefit from increasing brand recall, more strongly motivating action against the tobacco industry, and addressing alternative tobacco product use.

SO WHAT?

Young adults have high rates of smoking but few interventions target this high-risk group.

Social Branding is a novel approach utilizing psychographic targeting and commercial promotional strategies to decrease smoking among high-risk young adult bar patrons.

No controlled evaluations of social branding have been published to date.

This first controlled study of social branding in California found a significant decrease in smoking and a significantly lower rates of smoking in intervention cities compared to a control community.

Social branding interventions in bars and clubs may decrease tobacco use among high-risk young adults.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Cancer Institute grant U01 CA-154240 as part of the State and Community Tobacco Control initiative. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Clinical Trials Registration: This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT01686178.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Jeff Jordan is an employee of Rescue Agency, which implemented the intervention in this study.

References

- 1.Kasza KA, Ambrose BK, Conway KP, et al. Tobacco-product use by adults and youths in the United States in 2013 and 2014. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(4):342–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(6):908–916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, Sutherland I. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. Bmj. 2004;328(7455):1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, et al. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(4):341–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381(9861): 133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Using tobacco-industry marketing research to design more effective tobacco-control campaigns. JAMA 2002; 287(22):2983–2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):414–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang N, Ling PM. Impact of alcohol use and bar attendance on smoking and quit attempts among young adult bar patrons. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):e53–e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang N, Ling PM. Reinforcement of smoking and drinking: tobacco marketing strategies linked with alcohol in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1942–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang N, Lee YO, Ling PM. Association between tobacco and alcohol use among young adult bar patrons: a cross-sectional study in three cities. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilpin EA, White VM, Pierce JP. How effective are tobacco industry bar and club marketing efforts in reaching young adults? Tob Control. 2005;14(3):186–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendlin Y, Anderson SJ, Glantz SA. ‘Acceptable rebellion’: marketing hipster aesthetics to sell camel cigarettes in the US. Tob Control. 2010;19(3):213–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz SK, Lavack AM. Tobacco related bar promotions: insights from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002;11(suppl 1): I92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ling PM, Holmes LM, Jordan JW, Lisha NE, Bibbins-Domingo K. Bars, nightclubs, and cancer prevention: new approaches to reduce young adult cigarette smoking. Am J Prev Med. 2017; 53(3S1):S78–S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ling PM, Lee YO, Hong J, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Glantz SA. Social branding to decrease smoking among young adults in bars. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):751–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lisha NE, Jordan JW, Ling PM. Peer crowd affiliation as a segmentation tool for young adult tobacco use. Tob Control. 2016; 25(suppl 1):i83–i89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jordan JW, Stalgaitis CA, Charles J, Madden PA, Radhakrishnan AG, Saggese D. Peer crowd identification and adolescent health behaviors: results from a statewide representative study. Health Educ Behav. 2019;46(1):40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner DE, Fernandez P, Jordan JW, Saggese DJ. Freedom from chew: using social branding to reduce chewing tobacco use among country peer crowd teens. Health Educ Behav. 2019; 46(2):286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker MW, Navarro MA, Hoffman L, Wagner DE, Stalgaitis CA, Jordan JW. The hip hop peer crowd: an opportunity for intervention to reduce tobacco use among at-risk youth. Addict Behav. 2018;82:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran MB, Walker MW, Alexander TN, Jordan JW, Wagner DE. Why peer crowds matter: incorporating youth subcultures and values in health education campaigns. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(3):389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fallin A, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Hong JS, Ling PM. Wreaking “havoc” on smoking: social branding to reach young adult “partiers” in Oklahoma. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(1 suppl 1):S78–S85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalkhoran S, Lisha NE, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Ling PM. Evaluation of bar and nightclub intervention to decrease young adult smoking in New Mexico. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(2):222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fallin A, Neilands TB, Jordan JW, Ling PM. Social branding to decrease lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender young adult smoking. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(8):983–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA. The effect of support for action against the tobacco industry on smoking among young adults. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1449–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ling PM, Neilands TB, Glantz SA. Young adult smoking behavior: a national survey. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36(5): 389–394.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muhib FB, Lin LS, Stueve A, et al. A venue-based method for sampling hard-to-reach populations. Pub Health Rep. 2001;116(1 suppl):216–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Magnani R, Sabin K, Saidel T, Heckathorn D. Review of sampling hard-to-reach and hidden populations for HIV surveillance. Aids. 2005;19:S67–S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee YO, Jordan JW, Djakaria M, Ling PM. Using peer crowds to segment black youth for smoking intervention. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(4):530–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS 9.4; Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Syamlal G, Jamal A, King BA, Mazurek JM. Electronic cigarette use among working adults - United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(22):557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sutfin EL, Reboussin BA, Debinski B, Wagoner KG, Spangler J, Wolfson M. The impact of trying electronic cigarettes on cigarette smoking by college students: a prospective analysis. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(8):e83–e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doran N, Brikmanis K, Petersen A, et al. Does e-cigarette use predict cigarette escalation? A longitudinal study of young adult non-daily smokers. Prev Med. 2017;100:279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantey DS, Cooper MR, Loukas A, Perry CL. E-cigarette use and cigarette smoking cessation among Texas college students. Am J Health Behav. 2017;41(6):750–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]