Abstract

The limitations imposed on brain therapy by the blood-brain barrier (BBB) have warranted the development of carriers that can overcome and deliver therapeutic agents into the brain. We strategically designed liposomal nanoparticles encasing plasmid DNA for efficient transfection and translocation across the in vitro BBB model as well as in vivo brain-targeted delivery. Liposomes were surface modified with two ligands, cell-penetrating peptide (PFVYLI or R9F2) for enhanced internalization into cells and transferrin (Tf) ligand for targeting transferrin-receptor expressed on brain capillary endothelial cells. Dual-modified liposomes encapsulating pDNA demonstrated significantly (p<0.05) higher in vitro transfection efficiency compared to single-modified nanoparticles. R9F2Tf-liposomes showed superior ability to cross in vitro BBB and, subsequently, transfect primary neurons. Additionally, these nanoparticles crossed in vivo BBB and reached brain parenchyma of mice (6.6%) without causing tissue damage. Transferrin receptor-targeting with enhanced cell penetration are relevant strategies for efficient brain-targeted delivery of genes.

Keywords: liposome, brain, transferrin, PFVYLI, R9F2

Graphical abstract

Dual-modified liposomes surface modified with cell-penetrating peptides (PFVYLI and R9F2) and transferrin ligand were designed to overcome the blood brain barrier and efficiently deliver a plasmid DNA into the brain of mice. Our results showed the superior ability of R9F2Tf-liposomes to translocate across the in vitro blood brain barrier model and transfect neuronal cells as well as enhanced in vivo brain-targeted delivery properties. Thus, R9F2Tf-liposomes have potential as a carrier for brain-targeted gene delivery.

Background

The use of genes in an attempt to cure diseases or improve the ability of the body to fight diseases has become a promising therapeutic approach with the improvements in gene delivery systems.1 Gene therapy holds the potential for treating a wide range of diseases; however, gene transfer to the central nervous system poses significant challenges. The access of therapeutic agents into the brain is usually limited by the presence of anatomical and biochemical barriers, primarily the blood-brain barrier (BBB).2,3 Hence, the success of gene therapy relies on the development of a safe and effective gene vector that can deliver specific transgene to its target site and ensure its long-term expression.4

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are often incorporated in the design of efficient gene delivery systems because of their inherent ability to penetrate cells. CPPs are a diverse class of peptides that not only cross cellular membranes rapidly and efficiently but also carry cargos into cells without causing significant damage to cellular membranes. They possess several favorable properties such as endosomal escape, resist enzymatic degradation, and show high affinity for specific cell type or intracellular destination.5–7 CPPs were discovered more than 20 years ago, and until now, a variety of sequences have been studied and characterized.8,9

Recently, hydrophobic peptides have received much attention due to their ability to transport cargo into cells with minimal toxicity. The sequence PFVYLI is a known hydrophobic CPP derived from α1-antitrypsin used to deliver fluorescent probes, siRNA, and pro-apoptotic peptide in different cell lines.10,11 Integration of these hydrophobic CPPs to either N- or C-terminus of other cationic CPP can further enhance their cellular uptake and delivery capacity. For instance, the delivery efficiency of cationic R9 peptide was strongly enhanced after conjugation of two phenylalanine (F2) residues to C-terminus.12,13

Despite the shuttling properties of CPPs, these peptides lack cell specificity. Therefore, we designed liposomes either functionalized with PFVYLI (PF) or R9F2 and also conjugated to transferrin (Tf) for receptor targeting. Targeting transferrin receptors (TfR) using a high-affinity ligand facilitates the transport of Tf-conjugated liposomes across the BBB.14–16 As an additional strategy to promote transfection and protect plasmid DNA (pDNA) against enzymatic degradation, pDNA was complexed with chitosan. The electrostatic interaction between the cationic polymer and pDNA form polyplexes spontaneously, which prevents nuclease degradation by steric protection.17,18 We investigated cytotoxicity, cellular uptake, and uptake mechanism of the formulations in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells. The transfection efficiency of the designed gene carrier was first studied in vitro. Furthermore, we investigated the transport of liposomal formulations across the in vitro BBB co-culture model and, subsequently, their ability to transfect primary neuronal cells. Lastly, we assessed the biocompatibility and the ability of the liposomes to translocate across the BBB in vivo and reach brain parenchyma following intravenous injection into wild type mice. The strategy set applied in the development of efficient brain-targeted gene carrier contributes to overcoming the low efficiency of current treatments for brain diseases. The composition of liposomes, PEG incorporation, targeting ligands, and chitosan steric protection of pDNA together favor the active delivery of pDNA by designed liposomal nanoparticles into the nucleus of the brain cells.

Methods

Preparation and characterization of liposomal formulations

CPP and Tf were coupled to 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[succinimidyl(polyethylene glycol)] (DSPE-PEG2000-NHS), separately. CPP-PEG-lipid (4 mol %) was combined with DOPE/DOTAP/Cholesterol (45:45:2 mol %) in chloroform:methanol (2:1, v/v) and dried to form a lipid film, which was hydrated using HEPES buffer (pH 7.4). CPP-liposomes were stirred overnight with Tf-micelles (4 mol %).19 The incorporation of DSPE-PEG2000-Tf into the outer surface of liposomes resulted in CPPTf-liposomes. Plasmid DNA encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) and plasmid DNA encoding β-galactosidase (βgal) were purchased from Aldevron (Fargo, ND, USA). Chitosan-plasmid GFP or chitosan-plasmid β-gal polyplexes prepared at an N/P ratio of 5 was added to the hydration buffer for incorporation into liposomes. Hydrodynamic size and zeta potential were determined by the dynamic light scattering method using Zetasizer Nano ZS 90 (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK) at 25 °C. Morphological examination of liposomes was performed via transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100, JEOL) using 0.1% phosphotungstic acid aqueous solution as a negative stain. Percent of plasmid DNA encapsulated into liposomes was calculated by measuring fluorescent intensity at excitation/emission wavelengths of 354/458 nm using a Spectra Max M5 spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) after staining with Hoechst 33342 dye. The fluorescent intensity obtained following the addition of Triton X-100 was considered as 100%.

DNase protection assay

Liposomal formulations containing 1 μg of pGFP as chitosan-pGFP complexes were incubated for 60 min at 37 °C with 1 unit DNase I. Free pGFP was used as a negative control and pGFP with DNase I was used as a positive control. The reaction was stopped by adding 5 μL of EDTA solution (100 mM). Subsequently, 20 μL of heparin (5 mg/mL) was added and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C to release the pGFP from the complex. The released pGFP samples were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8% w/v) for 80 min at 80 V.20

Cell culture and animals

Primary cultures were obtained from the brain of 1-day-old rats.21 Briefly, meninges and vessels were removed from dissected brains. Brains were minced and incubated with DMEM containing 0.25% trypsin and DNase I (8μg/mL) at 37 °C. Cells were isolated and cultured in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (p/s). Primary neuronal cells were obtained after treatment with 10μM cytosine arabinoside on day 3. Mouse brain endothelial (bEnd.3) cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% p/s. Cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C.

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at North Dakota State University. Male/female Sprague Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories) and C57BL/6 mice (Jackson Laboratory) were housed under controlled temperature, 12 h dark and 12 h light cycles, and free access to food and water. The studies were conducted after 7 days of acclimation.

Blood compatibility study

Blood was freshly harvested from Sprague-Dawley rats into EDTA containing tubes and centrifuged three times at 1500 rpm for 10 min in PBS, pH 7.4, 10 mM CaCl2. Erythrocytes solution containing 1.5 × 107 cells was exposed to negative control (PBS), positive control (Triton X-100 1% v/v) and liposomal formulations (PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes) in different phospholipid concentrations (31.25–1000 μM) for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After incubation, cell suspension was centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed, and absorbance of released hemoglobin was measured using a spectrophotometer at 540 nm. Percent hemolysis was calculated by considering absorbance in the presence of Triton X-100 as 100% hemolysis.

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

Cell viability was evaluated in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells after treatment with liposomal formulations at 100, 200, 400, and 600 nM phospholipid concentration using MTT assay. All cell lines (1×104 cells/well) were plated on 96-well plate 24 h before performing the assay and exposed to liposomal formulations in serum-free media for 4 h. After that, the media was replaced, and cells were further cultured for 48 h. MTT (5 μg/well) was added to each well and incubated for 3 h. Subsequently, MTT solution was removed, and the formazan crystals were solubilized using DMSO. Absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer at 570 nm. The untreated cells were considered as a negative control (100% viability).

Cellular uptake study

bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells (1×105 cells/mL) were exposed to DiI-labeled liposomes (100 nM) for different time intervals. Cells were seeded onto 24-well plate 24 h before uptake analysis. At each time point, cells were rinsed with PBS (pH 7.4), nuclei of cells were stained with Hoechst 33342, and images were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Leica DMi8, IL, USA). Quantitative estimation of liposomal uptake was performed by lysis of cells in 0.5% Triton-X 100, followed by extraction of fluorescent dye in methanol. Fluorescence intensity was measured using a spectrophotometer (excitation wavelength: 553 nm, emission wavelength: 570 nm).

Cellular internalization mechanism

Brain endothelial (bEnd.3), glial, and primary neuronal cells (1×105 cells/mL) were treated with different endocytosis inhibitors such as sodium azide (10 mM), chlorpromazine (10 μg/mL), colchicine (100 μg/mL), and amiloride (50 μg/mL) for 30 min at 37 °C before application of DiI-liposomal formulations (100 nM).20 Following 4 h of the uptake process, fluorescence intensity was measured using a spectrophotometer (excitation/emission wavelength: 553–570 nm).

In vitro transfection efficiency

Cells (bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells) were treated with Lipofectamine 3000 and liposomal formulations (100 nM) containing either pGFP or pβgal complexes (1 μg), in the serum-free medium for 4 h. After that, cells were rinsed with PBS and incubated for 48 h. For pGFP transfection, GFP expression was analyzed using a fluorescence microscope, and quantitative evaluation was performed using FACS analysis (BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) laser excitation wavelength 488 nm, emission detection wavelength using optical filter FL1 533/30 nm.

For β-galactosidase expression, cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.4), and lysed using βgal assay buffer (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). β-galactosidase enzyme activity was quantified using β-galactosidase reagent assay at 420 nm. The total cellular protein level was determined by the micro BCA assay.

Design of in vitro co-culture BBB model

The in vitro BBB model was designed combining bEnd.3 and primary glial cells.22,23 Glial cells (1.5×104 cells/cm2) were seeded on the bottom side of transwell inserts (BD Biosciences, NC, USA) with 0.4 μm pore size and effective growth area of 0.33 cm2 in DMEM with 20% v/v FBS, and incubated overnight. About 1.5×104 cells/cm2 bEnd.3 cells were seeded on the upper side of culture inserts that were placed in 24-well plate (DMEM 20% v/v FBS). The formation of tight junctions was assessed measuring transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER) values using EVOM2 (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). Inserts containing bEnd.3 cells only on the upper side and inserts only with glial cells on the underside were also constructed and maintained similarly.

Transport across in vitro BBB model

The transport of labeled liposomal formulations was measured across the in vitro BBB model according to a modified method.19 Liposomal suspensions (100 nM) were added into inserts, which were placed in 24-well plate containing 0.5 mL PBS with 10% v/v FBS. After 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2, 4, and 8 h, the inserts were transferred to new wells with serum-PBS. Concentrations of fluorescent-labeled liposomes in the upper and the lower compartments were determined using a spectrophotometer (excitation/emission wavelengths: 568/583 nm, respectively). The intactness of the barrier layer was evaluated measuring TEER before and after (8 h) liposome transport across in vitro BBB using EVOM2. The apparent permeability coefficient for each liposomal formulation was calculated using the following equation:

where dQ/dt is the amount of liposomes transported per min (μg/min), A is the surface area of the transwell membrane (cm2), C0 is the initial concentration of liposomes (μg/mL), and 60 is the conversion factor from min to sec. Papp for liposomes was also evaluated across cell-free inserts.

Transfection efficiency in primary neuronal cells after liposome transport across in vitro BBB model

Primary neuronal cells were seeded on 24-well plate. Culture inserts containing the in vitro BBB model were placed in the same well having primary neuronal cells.24 Liposomal suspensions (100 nM) encapsulating pGFP (1 μg) were added to the upper compartment of inserts and incubated for 8 h. After that, the inserts were removed, and the media was replaced for fresh culture media. After 48 h incubation, GFP expression was analyzed using flow cytometer and fluorescence microscopy.

In vivo biodistribution and biocompatibility

Mice were randomly divided into three groups consisted of 6 animals each (3 males and 3 females). Each group was injected with either PBS, fluorescent-labeled R9F2-liposomes, and fluorescent-labeled R9F2Tf-liposomes administered via tail vein (~15.2 μmoles phospholipid/kg body weight). Qualitative evaluation of liposome biodistribution was performed by acquiring ex vivo fluorescent images of animals and organs using near-infrared (NIR) imaging after 24 h of administration. Quantification of liposomes was performed in the brain, liver, kidneys, lungs, heart, spleen, and blood. The organs were collected, rinsed with PBS, weighted, homogenized with PBS (200 μl), and fluorescent dye extracted in chloroform: methanol (2:1, v/v). The fluorescence intensity was measured by spectrophotometer at λex 560 nm and λem 580 nm. The standard curve for the measurement of the dye extracted from each organ was generated by vortexing free dye with the tissue samples from the corresponding organs of control animals (PBS administration). Data were normalized in units of percentage of injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g). The biocompatibility of liposomes was evaluated through histological examination of tissue sections. Tissues were sectioned into 30 μm slices, stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), and analysis of morphological alterations, signs of inflammation, necrosis, or cellular damage was performed.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey multiple comparison post-hoc test (GraphPad Prism 5.01- San Diego, CA, USA). At least four independent experiments were performed, and data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). The difference was considered statistically significant for p<0.05.

Results

Characterization of liposomal formulations

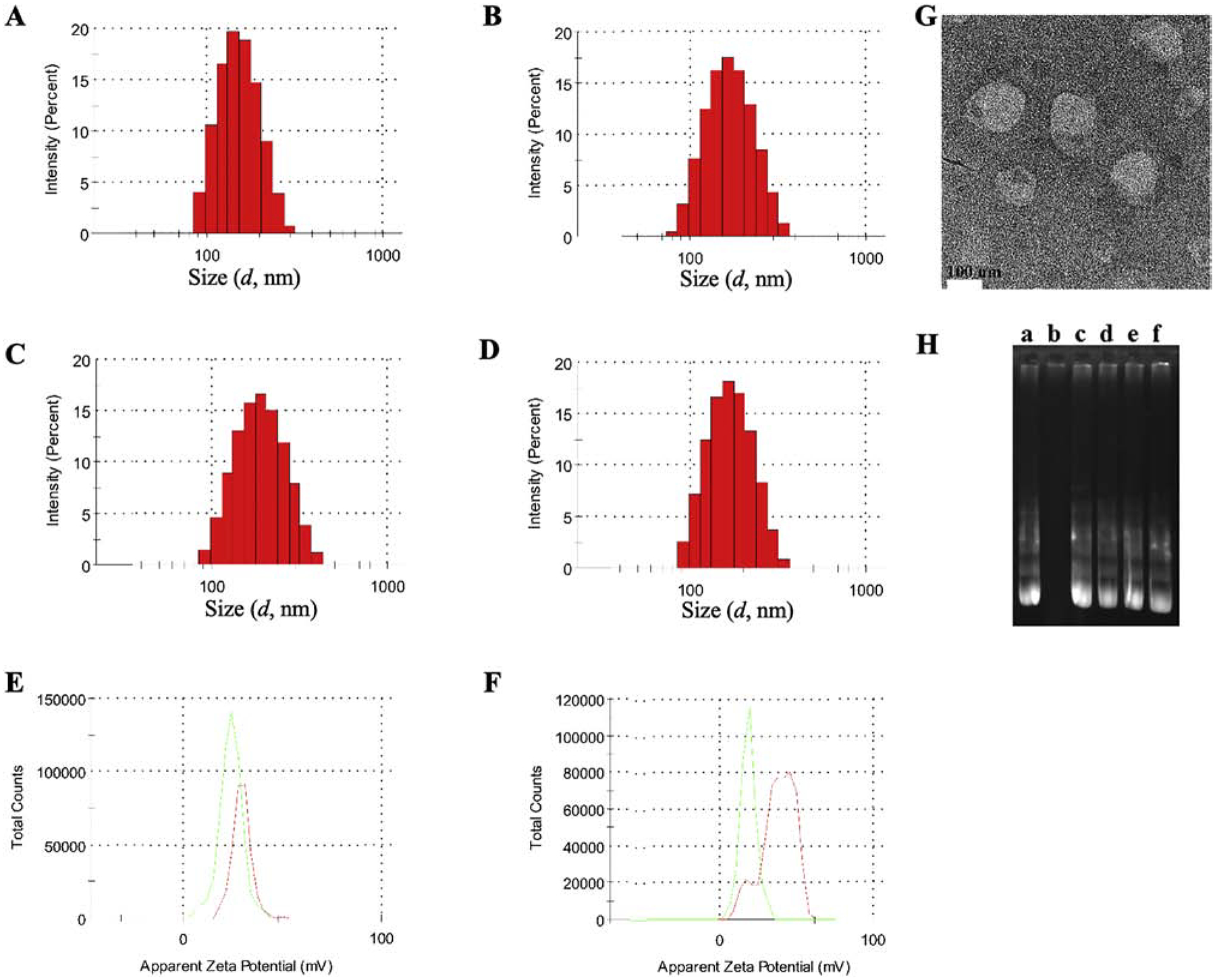

R9F2-lip and PF-liposomes were prepared via a two-step process, while the dual-modified R9F2Tf- and PFTf-liposomes were prepared via a three-step process: (1) preparation of a lipid film by evaporating chloroform: methanol solution of DOPE/DOTAP/Cholesterol/CPP-DSPE-PEG; (2) formation of R9F2-lip and PF-liposomes by hydrating the lipid film with HEPES buffer followed by ultrasound treatment; (3) formation of R9F2Tf-lip and PFTf-liposomes after the overnight stirring of Tf-micelles with R9F2-lip and PF-liposomes, respectively. Details of hydrodynamic size distribution and zeta potential characterization by the dynamic light scattering are present in Figure 1A–F. Smaller particle size was observed for PF-lip and PFTf-liposomes compared to R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes. The average particle size of PF-liposomes and PFTf-liposomes containing pDNA were 155.9±1.2 nm and 159.7±3.3 nm, and the zeta potentials were 31.4±0.5 mV and 27.3±2.1 mV, respectively. While the average size distribution of R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes containing pDNA were 164.2±2.3 nm and 168.7±2.1 nm, and the zeta potentials were 30.4±0.9 mV and 25.0±1.2 mV, respectively. The TEM micrograph (Figure 1G) revealed that our liposomal formulations surface modified with Tf and R9F2 have spherical morphology. The encapsulation of pDNA into liposomal formulations was not negatively affected by different plasmid DNA. High encapsulation efficiencies of plasmid DNAs were obtained for all liposomal formulations, which were above 80% (Table S1).

Figure 1.

Hydrodynamic size distribution of (A) PF-lip, (B) PFTf-lip, (C) R9F2-lip and (D) R9F2Tf-lip, determined by DLS. Zeta potential of (E) PF-lip (red) and PFTf-lip (green) and (F) R9F2-lip (red) and R9F2Tf-lip (green). (G) TEM image of R9F2Tf-liposomes encapsulating chitosan-pDNA complexes (Scale 100 nm). (H) Protection of plasmid GFP encapsulated into liposomal formulations against DNase I digestion. Lane a = free pGFP, lane b-f = pGFP, PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-lip, respectively + DNase I.

DNase protection assay

Gene delivery systems can provide significant protection of the entrapped gene molecule against enzymatic degradation. As represented in Figure 1H, the pDNA bands from the liposomal formulations + DNase I treated groups (lane c-f, Figure 1H) were similar to the band in the untreated group (lane a, Figure 1H). The absence of band at lane b confirms the vulnerability of free pDNA to enzymatic degradation. The results suggested that the polyplexes (pDNA-chitosan) in the liposomal formulations were sufficiently protected from DNase degradation.

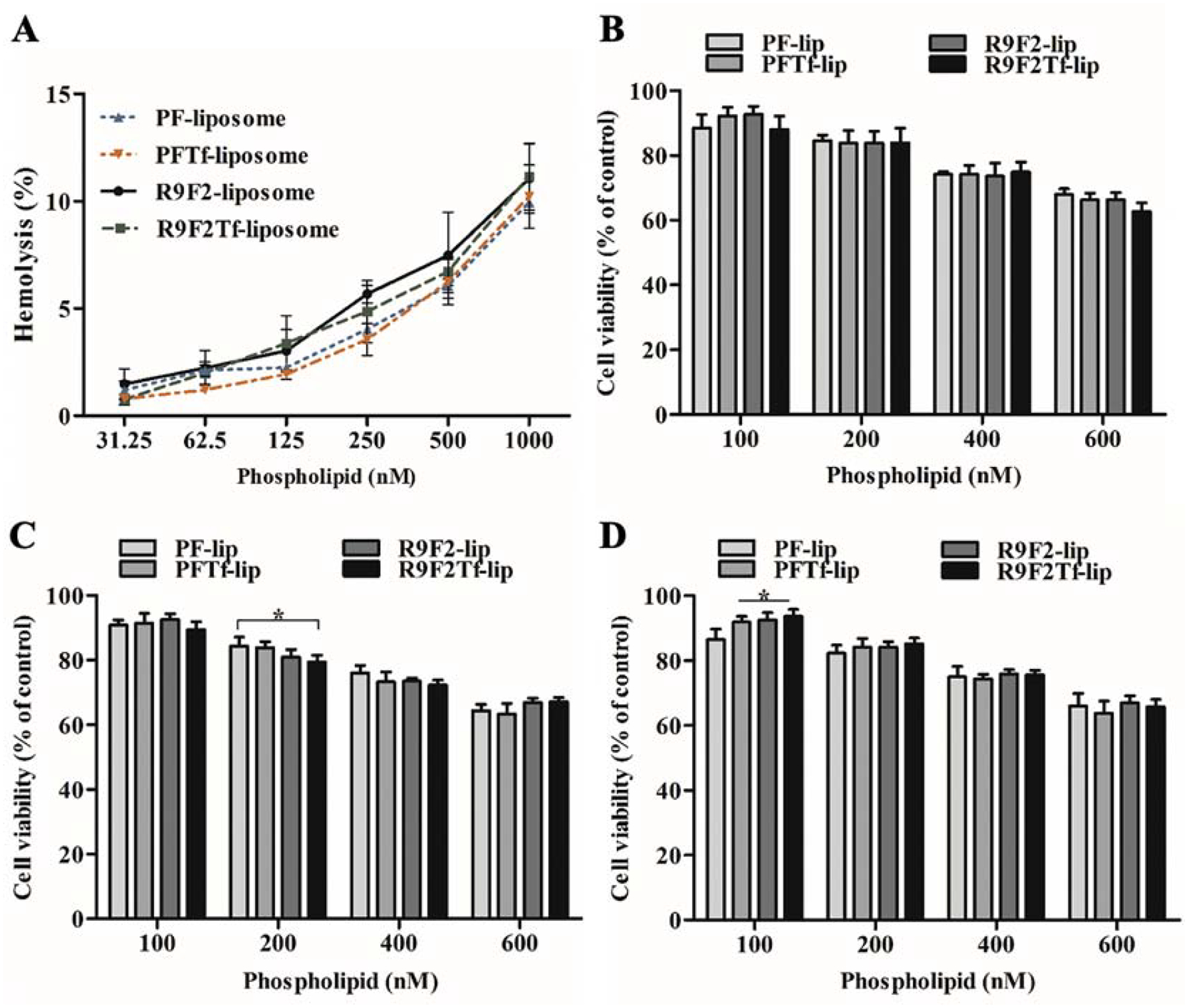

Blood compatibility study

Liposomal formulations caused approximately 1% hemolysis at 31.25 nM phospholipid concentration, as shown in Figure 2A. The hemolysis percentage increased gradually with the increase in phospholipid concentration, reaching the average of 10.6% hemolysis at 1000 nM.

Figure 2.

(A) Hemolytic activity of PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes (31.25–1000 nM phospholipid concentration) in rat erythrocytes after 1 h incubation at 37 °C. Percent hemolysis of 1% v/v Triton X-100 was considered 100% hemolysis. Viability of bEnd.3 (B), glial (C) and primary neuronal cells (D) after incubation with PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes at different phospholipid concentrations (100, 200, 400 and 600 nM) for 4 h at 37 °C. Viability of untreated cells were used as control and considered 100%. All data are represented as mean ± SD (n=5). Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) are shown as (*).

In vitro cytotoxicity assay

The in vitro cytotoxicity of PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip, and R9F2Tf-liposomes was detected in bEnd.3 (Figure 2B), glial (Figure 2C), and primary neuronal cells (Figure 2D) after 4 h incubation using MTT assay. The cell viability decreased as liposomal concentration increased. At 100 nM phospholipid concentration, over 90% of the cells were viable. While at 600 nM phospholipid concentration, approximately 65% of the cells were viable. There were no significant differences between the formulations, indicating they had uniformly low cytotoxicity at 100 nM phospholipid concentration. Therefore, 100 nM concentration was chosen for the following experiments.

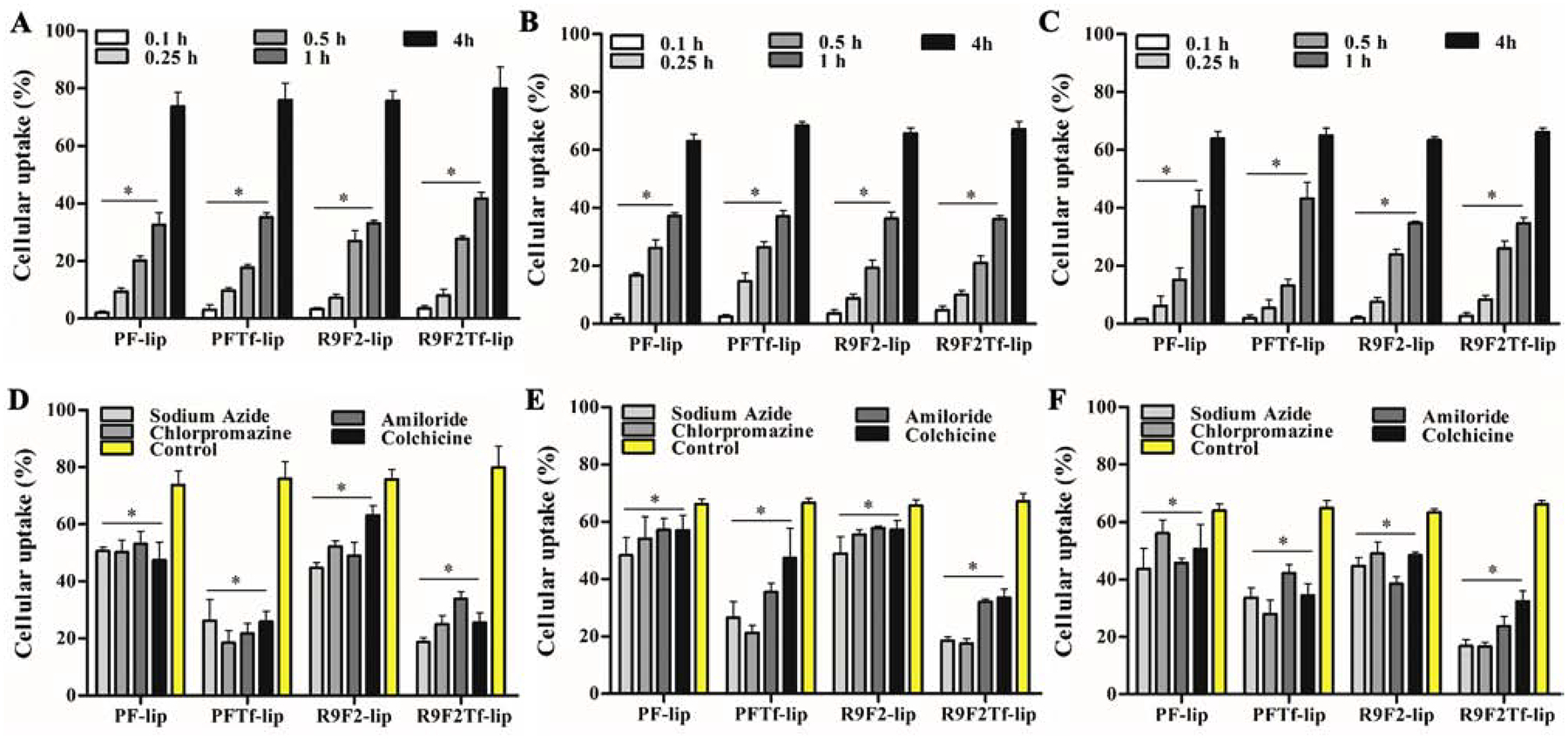

Liposome internalization into cells

The uptake of liposomal formulations in bEnd.3 (Figure 3A), glial (Figure 3B), and primary neuronal cells (Figure 3C) significantly increased with prolongation of incubation time. At 4 h, the average uptake of liposomal formulations was approximately 76.3%, 65.8%, and 64.5% in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells, respectively. There is increasing evidence to suggest some CPPs can directly diffuse across the cell membrane, thus an energy-independent process as shown in Figure 3D (bEnd.3 cells), 3E (glial cells), and 3F (primary neuronal cells), and also demonstrated by fluorescence microscopy (bEnd.3, Figure S1A; glial, Figure S1B; and primary neuronal cells, Figure S1C). Depletion of intracellular ATP caused by sodium azide pre-incubation resulted in significant (p<0.05) reduction in uptake of PF-liposomes (reduction of 31%, 27%, and 31% uptake in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells, respectively) and R9F2-liposomes (reduction of 40%, 25%, and 29% uptake in bEnd.3, glial and primary neuronal cells, respectively). Similarly, a significant (p<0.05) inhibition was observed on dual-functionalized liposomes uptake, PFTf-liposomes (reduction of 75%, 60%, and 49% uptake in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells, respectively) and R9F2Tf-liposomes (reduction of 70%, 72%, and 74% uptake in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells, respectively), as compared with untreated cells. ATP dependence of PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes uptake suggested that endocytosis is the primary mechanism of uptake for these liposomes.

Figure 3.

Percent uptake of PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes in (A) bEnd.3, (B) glial and (C) primary neuronal cells after 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1 and 4 h of incubation. Percent uptake of PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes after 4 h of incubation in (D) bEnd.3, (E) glial and (F) primary neuronal cells pretreated with endocytosis inhibitors (sodium azide, chlorpromazine, amiloride and colchicine). Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=5).

When the same cell lines were pre-incubated with chlorpromazine, the percent uptake of PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes was reduced by ~70%, which indicates the involvement of clathrin-mediated endocytosis on uptake of dual-functionalized liposomes. Inhibition of macropinocytosis by amiloride reduced significantly (p<0.05) the cellular uptake of liposomal formulations, especially of PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes. Pretreatment of cells with colchicine resulted in a significant (p<0.05) decrease in cellular internalization of PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes. Colchicine treatment has been reported to block the endocytosis pathway based on lipid raft/caveolae via depolymerization of microtubules.25

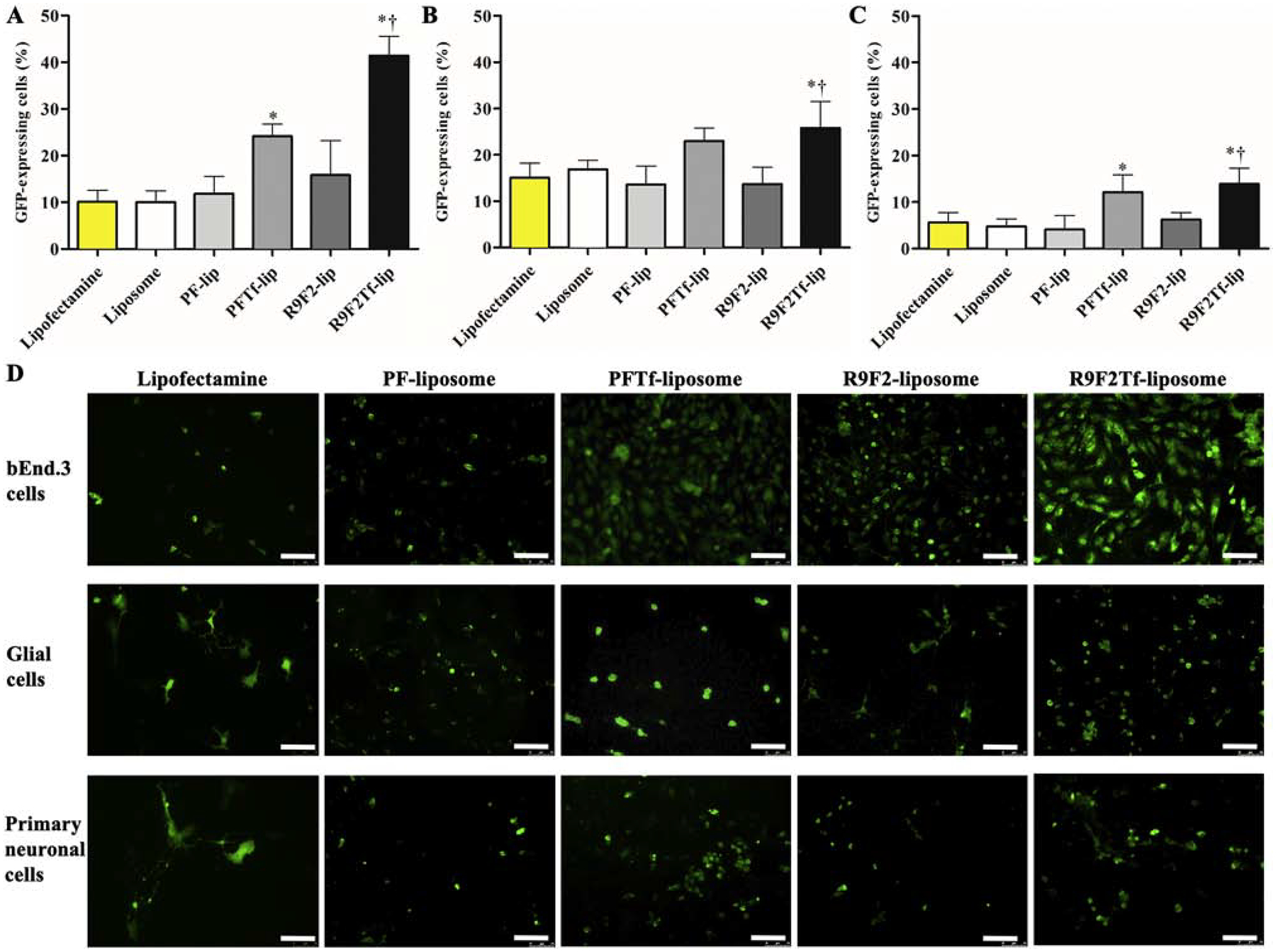

In vitro transfection

Transfection efficiencies of liposomal formulations were compared to commercially available cationic transfection reagent Lipofectamine 3000. Liposomes with dual modification induced significantly higher GFP expression as compared to liposomes with single modification, liposome without surface modification, and Lipofectamine 3000/pGFP, in bEnd.3 (Figure 4A), glial (Figure 4B), and primary neuronal cells (Figure 4C). Additionally, R9F2Tf-liposomes showed superior ability to induce GFP expression in bEnd.3 (41.4% versus 24.1% for PFTf-lip), glial (25.8% versus 22.9% for PFTf-lip), and primary neuronal cells (13.9% versus 12.0% for PFTf-lip), Figure 4D.

Figure 4.

In vitro transfection efficiency of Lipofectamine 3000, Liposome (without surface modification), PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes encapsulating 1 μg chitosan-pGFP complexes in (A) bEnd.3, (B) glial and (C) primary neuronal cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4). Statistically significant (p<0.05) differences are shown as (*) with Lipofectamine 3000 and Liposome (without surface modification), and (†) with R9F2-liposomes. D) Fluorescence microscopy images of GFP expression in bEnd.3, glial and primary neuronal cells treated with PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes encapsulating 1μg chitosan-pGFP complexes. Scale bar, 100 μm.

The transfection efficiencies of liposomal formulations were also evaluated using the pβgal reporter gene. R9F2Tf-liposomes encapsulating pβgal showed a significantly higher ability to induce protein expression in bEnd.3 (Figure S2A), glial (Figure S2B), and primary neuronal cells (Figure S2C). R9F2Tf-liposomes increased 2.7-fold, 3.4-fold, and 2.6-fold βgal activity in bEnd.3, glial, and primary neuronal cells, respectively, when compared to βgal activity induced by PFTf-liposomes.

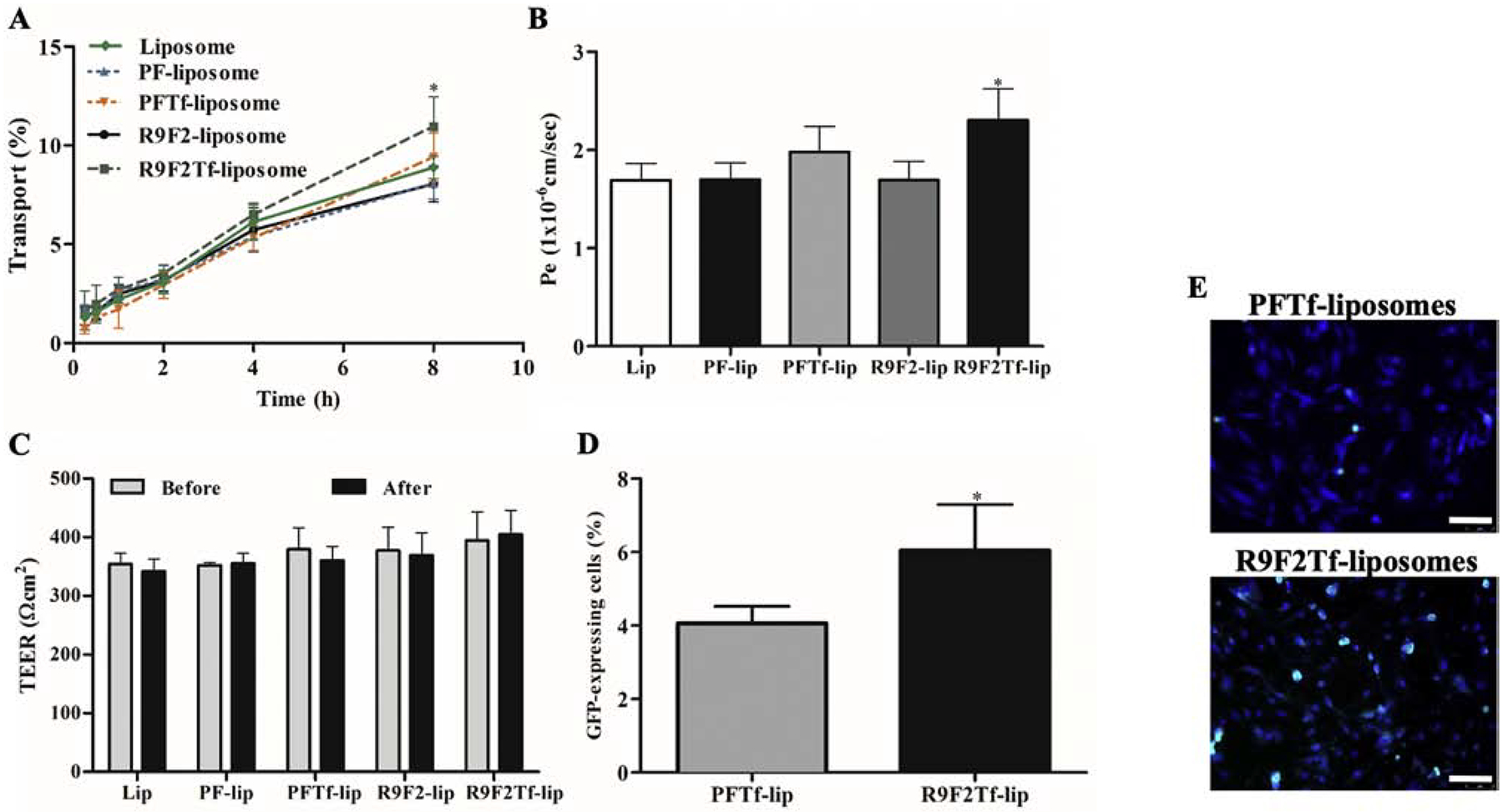

Transport of liposomal formulations across in vitro BBB model, endothelial cell permeability and TEER

An in vitro BBB model established by the co-culture of bEnd.3 and glial cells was designed to evaluate the ability of liposomal formulations to overcome the barrier layer. Liposomes gradually crossed the designed in vitro BBB model over a period of 8 h. The dual modified liposomes showed a higher ability to overcome that barrier compared to single modified liposomes, shown in Figure 5A. Notably, R9F2Tf-liposomes demonstrated approximately 11% translocation across the barrier layer, which was significantly higher as compared to liposomes without surface modification (8.8%), PFTf-lip (9.4%), PF-lip (8%) and R9F2-liposomes (8%). As a consequence, significantly (p<0.05) higher endothelial cell permeability of R9F2Tf-liposomes was also observed (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

A) Percent transport of Liposome (without surface modification), PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes across in vitro BBB model over a period of 8 h. Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference are shown as (*) with PF-lip, PFTf-lip and R9F2-liposomes. B) Endothelial cell permeability (Pe, expressed as 1×10−6 cm/sec) coefficient for Liposome (without surface modification), PF-lip, PFTf-lip, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes. Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference is shown as (*) with PF- and R9F2-liposomes. C) Transendothelial electrical resistance (TEER, expressed as Ωcm2) of in vitro BBB model before and after 8 h of incubation with liposomal formulations. No significant difference among the TEER of the liposomal formulations before and after liposome transport. D) In vitro transfection efficiency of PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes encapsulating 1 μg chitosan-pGFP complexes in primary neuronal cells after crossing the in vitro BBB model. All data are expressed as mean ± SD (n=4). Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference is shown as (*) with PFTf-liposomes. E) Fluorescence microscopy images of GFP expression in primary neuronal cells treated with PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes encapsulating 1μg chitosan-pGFP complexes after transport of liposomes across in vitro BBB model. Scale bar, 100 μm.

The integrity of the in vitro barrier was assessed by TEER measurements before and after 8 h incubation of liposomal formulations in the co-culture insert. TEER values before and after the transport experiment were not significantly (p<0.05) different for all formulations (Figure 5C), indicating no damage to the in vitro BBB.

Transfection efficiency in primary neuronal cells after transport of liposomes across in vitro BBB model

In order to evaluate the ability of liposomal formulations to transfect cells following translocation across the in vitro BBB model, PFTf-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes containing pDNA were added into co-cultured inserts placed in plates containing primary neuronal cells. PFTf-liposomes and R9F2Tf-liposomes were chosen for this study due to their superior ability to transfect the cells directly and to cross the in vitro BBB model as compared to the other liposomal formulations. R9F2Tf-liposomes showed significantly higher ability to transfect primary neuronal cells as compared to PFTf-liposomes. PFTf-liposomes showed 4%, while R9F2Tf-liposomes demonstrated 9.2% GFP expression in primary neuronal cells (Figure 5D). The expression of GFP by primary neuronal cells after treatment with liposomal formulations containing plasmid DNA encoding GFP was shown in Figure 5E.

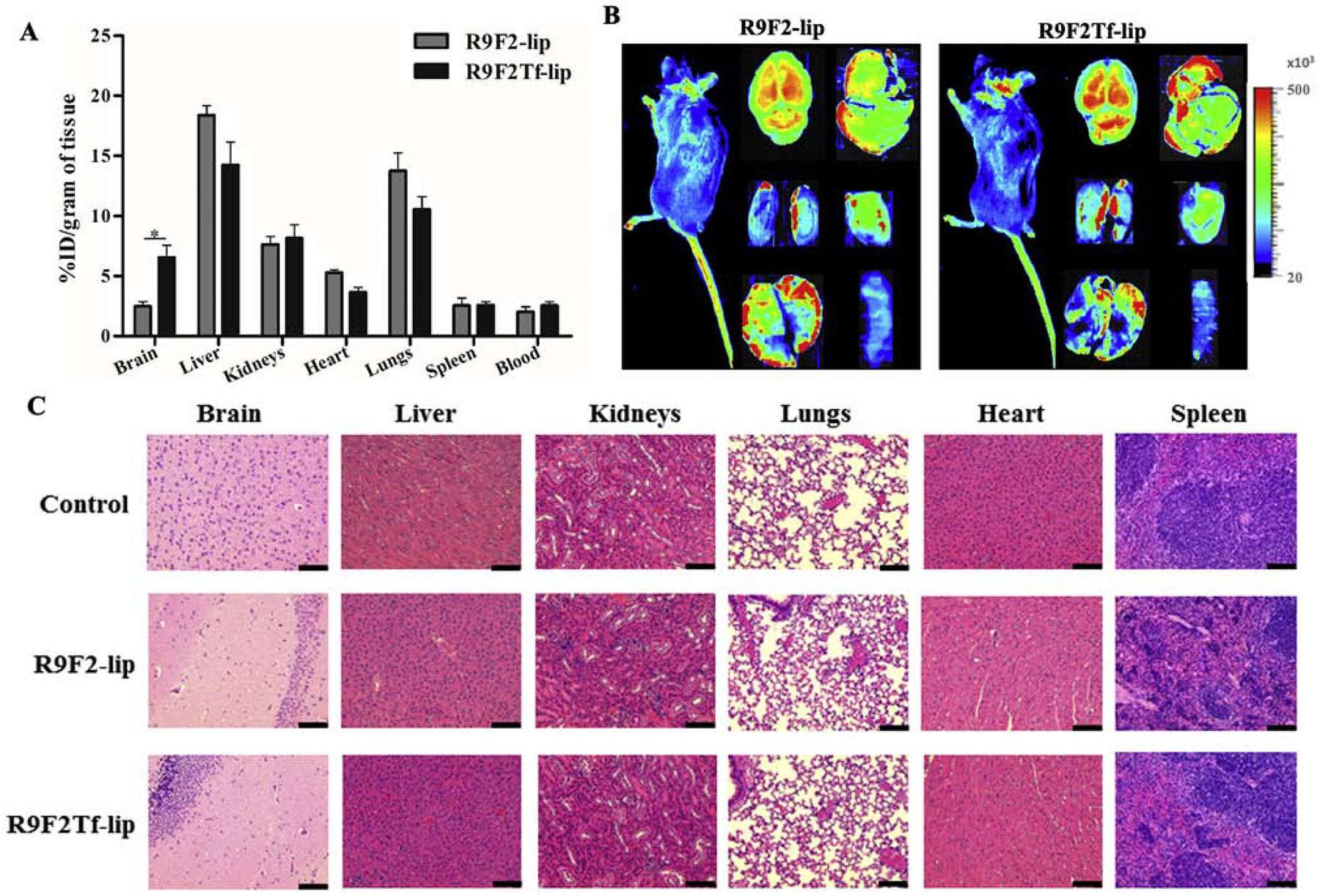

In vivo biodistribution and biocompatibility

Based on the in vitro transfection efficiency and transport across in vitro BBB model results, R9F2Tf-modified liposomes were chosen for in vivo studies and compared to R9F2-liposomes. The accumulation of liposomal formulations in different organs (brain, liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, spleen, and blood) was determined after 24 h of liposome administration. The quantitative characterization showed a significantly higher accumulation of R9F2Tf-liposomes (6.6%) in the brain as compared to R9F2-liposomes (2.5%) (Figure 6A and B). The amount quantified of the tested formulations in the other organs were not significantly different. Histological evaluation of tissue sections did not show any signs of tissue damage, inflammation, necrosis, or even change in cell morphology (Figure 6C). The tissue samples from animals administered with PBS were used as control.

Figure 6.

In vivo biodistribution of R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes (~15.2 μM phospholipid/kg body weight) in C57BL/6 mice after 24 h of intravenous administration. (A) Quantification of fluorescently labeled-liposomes was performed in brain, liver, kidneys, heart, lungs and spleen (n=6). Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistically significant (p<0.05) difference is shown as (*). (B) Near-Infrared (NIR) imaging of relative fluorescence intensity of mice, brain, liver, kidneys, heart, lungs and spleen from C57BL/6 mice 24 h after administration of R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes. (C) Histological analysis through H&E staining of organ sections of C57BL/6 mice subjected to various liposomal formulations treatment. Representative sections of brain, liver, kidneys, heart, lungs and spleen of mice treated with PBS, R9F2-lip and R9F2Tf-liposomes. The tissue sections from mice administered with PBS were used as controls. Scale bar, 100 μm.

Discussion

Although the number of publications exploring the potential of nanoparticles as brain-targeted drug delivery is increasing, it is still important to explore new approaches for the treatment of CNS diseases due to the limitations of the existing formulations and delivery strategies.26 This study focused on the development and characterization of the brain targeted stealth-delivery systems as an efficient gene carrier technology. Liposomes were surface modified with Tf and CPP to enhance their transport across the BBB via a receptor and adsorptive mediated transcytosis.27

Studies of cellular internalization of liposomes encasing pDNA have significant importance in providing a mechanistic insight on cellular processing and, consequently, define the functionalities needed for an optimized gene carrier.28 The cationic character of liposomes probably facilitated the internalization, in a time-dependent manner, through electrostatic interaction to the negatively charged cellular membrane.29 The internalization of liposomal carriers has been reported to occur preferentially via endocytosis pathways and dependent on several factors such as physicochemical properties (particle size, surface charge, surface moieties, for instance) and the cell line.29

Previous studies performed with CPP-conjugated liposomes and Tf-CPP conjugated liposomes have shown that various cellular uptake mechanisms drove cellular internalization, but with specific extent for each formulation and cell type.10,16,30,31 Using fluorescent-labeled liposomes, we showed that endocytosis-mediated mechanisms predominated when conjugating Tf to CPP-liposome, with clathrin-mediated endocytosis exerting significant contribution. The observed difference in the mechanisms of internalization between CPP-liposomes and CPP-Tf-liposomes suggests that interaction of Tf to TfR has a vital role in the energy-dependent liposome internalization. However, Tf-TfR as a brain target system can be a saturable process. Concomitant presence of Tf and CPPs on liposome surface propitiated liposome uptake through multisite binding and electrostatic attraction binding and, consequently, maintaining a high rate of uptake even in case of TfR saturation.

Following the uptake studies, we observed the superior ability of R9F2Tf-liposomes loaded pDNA to transfect all cell lines tested, which was also superior as compared to the reported transfection efficiency of Tf-liposomes in the same cell lines.32 Transfection efficiency can be influenced by many factors, including the properties of the gene carrier, nature of plasmid DNA, cellular mechanisms of uptake, endosomal escape, intracellular delivery routes as well as cell type.33,34 Therefore, our results suggest the effect of liposome surface modification on transfection, and the role of physicochemical properties of PF and R9F2 on this process. Some studies have reported that arginine-rich CPP such as nona-arginine (R9) peptides eventually escape from endosome through endosome acidification and/or changes in lipid composition of endosomes upon maturation.35–37 Increase in the hydrophobicity by conjugating two phenylalanines to R9 C-terminus have shown to enhance the interaction with the cell membrane and, consequently improved uptake of the cargo.13 Likely, R9F2Tf-liposomes would be endocytosed into clathrin-coated vesicles, then sorted into early endosomes that mature into late endosomes and lysosomes, where R9F2 would promote lipid fusion between liposomes and lysosomal membrane through electrostatic interaction. Following the formation of the fusion pore, liposome cargo would be released into the cytoplasm. The presence of DOPE has shown to contribute to the endosomal escape of arginine-rich liposomes due to its fusogenic properties.38,39 The ability of nona-arginine (R9) peptides to escape from endosomes and transport the pDNA complex to the nucleus may have positively contributed to transfection efficiency of R9F2-liposomes in glial cells and primary neurons differently as compared to PFTf-liposomes. The investigation of differential transfection efficiency of liposomal formulations in different cell lines will be include in our future studies. Successful cellular transfection not only relies on the internalization of DNA into cells and subsequent transcription, but also on a number of intracellular events that allow the DNA to move from the cytoplasm into the nucleus before transcription initiation.40,41 Besides endosomal escape, the transport of pDNA complexes to the nucleus mediated by motor proteins can significantly impact gene transfection. Dynein motor protein may interact with greater affinity with R9F2Tf-liposomes and move the complex in the microtubule towards the nucleus as compared to the single-modified liposomes leading to higher transfection of R9F2Tf-liposomes.

Consistently, R9F2Tf-liposomes showed higher transport across the in vitro BBB model, and subsequently, transfected primary neuronal cells. As expected, the low cytotoxicity of liposomal formulations at 100 nM did not cause membrane disruption to the in vitro BBB layer. The established in vitro BBB co-culture model has been recognized as a good model for screening of formulations with better brain penetration due to the high correlation demonstrated with the permeability of in vivo BBB.22,23 Our findings indicate that both Tf and R9F2 modifications on the gene-loaded liposomes play a major role in the transport of the dual-modified liposomes across the BBB model. The receptor-mediated transport of liposomes by Tf had the cooperation of R9F2 to enhance the transcytosis. The amount of liposomes transported across the in vitro layer was comparatively higher than the values observed in studies, which also evaluated the translocation of modified-liposomes across in vitro BBB.16,23,42 Therefore, the results suggested that R9F2Tf-liposomes would hold a great potential to cross in vivo BBB, deliver the pDNA into the brain cells, and promote the transfection.

The biodistribution studies confirmed the ability of R9F2Tf-liposomes to translocate the BBB and reach brain parenchyma. Despite the detection in other tissues, especially in the liver and lungs, the qualitative and quantitative evaluation proved the enhanced brain-targeting delivery of dual-modified liposomes. As suggested by Cabezόn et al.,43 internalized liposomal nanoparticles can undergo at least two different courses. They can be sorted into the endosomal cycle and be degraded by lysosomal enzymes. Also, they can be transcytosed across brain capillary endothelial cells and released in the brain parenchyma, which demonstrates the ability of the nanoparticles to escape the endosomes. We believe that, together with Tf, R9F2 facilitate liposomes interaction with endothelial cell membrane resulting in nanoparticle internalization. Additionally, the CPP would promote endosomal escape and the release of cargo into the brain parenchyma. It is important to note that some groups working with transferrin-receptor targeted liposomes have observed lower levels of nanoparticle in the brain parenchyma in vivo after i.v. injection15,44,45 as compared to R9F2Tf-liposomes levels. These results show that the design of dual-modified liposomes for brain-targeted and enhanced cellular internalization properties can be a strategic approach for the development of gene delivery systems capable of translocation across the BBB and delivery of pDNA to brain cells.

We designed dual-mediated liposome CPPTf-liposomes by conjugating Tf and CPP moieties to liposomes via DSPE-PEG for brain-targeted gene delivery. A time-dependent internalization of nanoparticles into cells occurred through multiple mechanisms. Caveolae and clathrin-mediated endocytosis played an important role as the main pathways involved in the ability of liposomes to overcome in vitro and in vivo BBB. The physicochemical properties of R9F2 assisted R9F2Tf-liposomes in the enhanced in vitro transfection and superior ability to translocate in vitro and in vivo BBB, which reflected in the significant quantification of the dual-functionalized liposomes in the brain of mice. Transferrin receptor targeting with enhanced cellular internalization has demonstrated to be a robust strategy in the design of gene delivery systems with brain-targeted properties. Additional studies are needed to describe the extension of the therapeutic potential of these formulations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

B.S.R. is doctoral fellowship from The Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil) with a scholarship for B.S.R (Full Doctorate Fellowship (GDE): 221327/2014-2).

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (Grant R01AG051574).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ibraheem D, Elaissari A, Fessi H. Gene therapy and DNA delivery systems. Int J Pharm 2014; 459: 70–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pandey PK, Sharma AK, Gupta U. Blood brain barrier: An overview on strategies in drug delivery, realistic in vitro modeling and in vivo live tracking. Tissue Barriers 2016; 4: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furtado D, Björnmalm M, Ayton S, et al. Overcoming the Blood-Brain Barrier: The Role of Nanomaterials in Treating Neurological Diseases. Adv Mater; 30 Epub ahead of print 2018. DOI: 10.1002/adma.201801362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley M, Vermerris W. Recent Advances in Nanomaterials for Gene Delivery—A Review. Nanomaterials 2017; 7: 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guidotti G, Brambilla L, Rossi D. Cell-Penetrating Peptides: From Basic Research to Clinics. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2017; 38: 406–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copolovici DM, Langel K, Eriste E, et al. Cell-penetrating peptides: Design, synthesis, and applications. ACS Nano 2014; 8: 1972–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milletti F. Cell-penetrating peptides: Classes, origin, and current landscape. Drug Discov Today 2012; 17: 850–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green M, Loewenstein PM. Autonomous functional domains of chemically synthesized human immunodeficiency virus tat trans-activator protein. Cell 1988; 55: 1179–1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell 1988; 55: 1189–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai D, Gao W, He B, et al. Hydrophobic penetrating peptide PFVYLI-modified stealth liposomes for doxorubicin delivery in breast cancer therapy. Biomaterials 2014; 35: 2283–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Q, Wang J, Zhang H, et al. The anticancer efficacy of paclitaxel liposomes modified with low-toxicity hydrophobic cell-penetrating peptides in breast cancer: An: in vitro and in vivo evaluation. RSC Adv 2018; 8: 24084–24093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuman BW, Stein D a, Kroeker AD, et al. Antisense morpholino-oligomers directed against the 5’ end of the genome inhibit coronavirus proliferation and growth. J Virol 2004; 78: 5891–5899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moulton HM, Nelson MH, Hatlevig SA, et al. Cellular Uptake of Antisense Morpholino Oligomers Conjugated to Arginine-Rich Peptides. Bioconjug Chem 2004; 15: 290–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.dos Santos Rodrigues B, Oue H, Banerjee A, et al. Dual functionalized liposome-mediated gene delivery across triple co-culture blood brain barrier model and specific in vivo neuronal transfection. J Control Release 2018; 286: 264–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng C, Ma C, Bai E, et al. Transferrin and cell-penetrating peptide dual-functioned liposome for targeted drug delivery to glioma. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8: 1658–1668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnsen KB, Burkhart A, Melander F, et al. Targeting transferrin receptors at the blood-brain barrier improves the uptake of immunoliposomes and subsequent cargo transport into the brain parenchyma. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buschmann MD, Merzouki A, Lavertu M, et al. Chitosans for delivery of nucleic acids. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2013; 65: 1234–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao S, Sun W, Kissel T. Chitosan-based formulations for delivery of DNA and siRNA. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2010; 62: 12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma G, Modgil A, Sun C, et al. Grafting of cell-penetrating peptide to receptor-targeted liposomes improves their transfection efficiency and transport across blood-brain barrier model. J Pharm Sci 2012; 101: 2468–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Layek B, Haldar MK, Sharma G, et al. Hexanoic acid and polyethylene glycol double grafted amphiphilic chitosan for enhanced gene delivery: Influence of hydrophobic and hydrophilic substitution degree. Mol Pharm 2014; 11: 982–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumners C, Fregly MJ. Modulation of angiotensin II binding sites in neuronal cultures by mineralocorticoids. Am J Physiol 1989; 256: C121–C129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakagawa S, Deli MA, Kawaguchi H, et al. A new blood-brain barrier model using primary rat brain endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Neurochem Int 2009; 54: 253–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helms HC, Abbott NJ, Burek M, et al. In vitro models of the blood–brain barrier: An overview of commonly used brain endothelial cell culture models and guidelines for their use. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 862–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue Q, Liu Y, Qi H, et al. A novel brain neurovascular unit model with neurons, astrocytes and microvascular endothelial cells of rat. Int J Biol Sci 2013; 9: 174–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin M, Snider MD. Role of microtubules in transferrin receptor transport from the cell surface to endosomes and the Golgi complex. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 18390–18397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou Y, Peng Z, Seven ES, et al. Crossing the blood-brain barrier with nanoparticles. J Control Release 2018; 270: 290–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnsen KB, Moos T. Revisiting nanoparticle technology for blood-brain barrier transport: Unfolding at the endothelial gate improves the fate of transferrin receptor-targeted liposomes. J Control Release 2016; 222: 32–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yameen B, Choi W Il, Vilos C, et al. Insight into nanoparticle cellular uptake and intracellular targeting. J Control Release 2014; 190: 485–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang JH, Jang WY, Ko YT. The Effect of Surface Charges on the Cellular Uptake of Liposomes Investigated by Live Cell Imaging. Pharm Res 2017; 34: 704–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watkins CL, Brennan P, Fegan C, et al. Cellular uptake, distribution and cytotoxicity of the hydrophobic cell penetrating peptide sequence PFVYLI linked to the proapoptotic domain peptide PAD. J Control Release 2009; 140: 237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuan M, Qiu Y, Zhang L, et al. Targeted delivery of transferrin and TAT co-modified liposomes encapsulating both paclitaxel and doxorubicin for melanoma. Drug Deliv 2016; 23: 1171–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.dos Santos Rodrigues B, Banerjee A, Kanekiyo T, et al. Functionalized liposomal nanoparticles for efficient gene delivery system to neuronal cell transfection. Int J Pharm 2019; 566: 717–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Figueroa E, Bugga P, Asthana V, et al. A mechanistic investigation exploring the differential transfection efficiencies between the easy - to - transfect SK - BR3 and difficult - to - transfect CT26 cell lines. J Nanobiotechnology 2017; 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maurisse R, De Semir D, Emamekhoo H, et al. Comparative transfection of DNA into primary and transformed mammalian cells from different lineages. BMC Biotechnol 2010; 10: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang ST, Zaitseva E, Chernomordik LV., et al. Cell-penetrating peptide induces leaky fusion of liposomes containing late endosome-specific anionic lipid. Biophys J 2010; 99: 2525–2533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melikov K, Hara A, Yamoah K, et al. Efficient entry of cell-penetrating peptide nona-arginine into adherent cells involves a transient increase in intracellular calcium. Biochem J 2015; 471: 221–230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Madani F, Abdo R, Lindberg S, et al. Modeling the endosomal escape of cell-penetrating peptides using a transmembrane pH gradient. Biochim Biophys Acta - Biomembr 2013; 1828: 1198–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Sayed A, Futaki S, Harashima H. Delivery of Macromolecules Using Arginine-Rich Cell-Penetrating Peptides: Ways to Overcome Endosomal Entrapment. AAPS J 2009; 11: 13–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu C, Liu XN, Wang GL, et al. A dual-mediated liposomal drug delivery system targeting the brain: Rational construction, integrity evaluation across the blood-brain barrier, and the transporting mechanism to glioma cells. Int J Nanomedicine 2017; 12: 2407–2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Douglas KL, Piccirillo CA, Tabrizian M. Cell line-dependent internalization pathways and intracellular trafficking determine transfection efficiency of nanoparticle vectors. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2008; 68: 676–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai H, Lester GMS, Petishnok LC, et al. Cytoplasmic transport and nuclear import of plasmid DNA. Biosci Rep 2017; 37: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xie Y, Ye L, Zhang X, et al. Transport of nerve growth factor encapsulated into liposomes across the blood-brain barrier: In vitro and in vivo studies. J Control Release 2005; 105: 106–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cabezón I, Manich G, Martín-Venegas R, et al. Trafficking of Gold Nanoparticles Coated with the 8D3 Anti-Transferrin Receptor Antibody at the Mouse Blood-Brain Barrier. Mol Pharm 2015; 12: 4137–4145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sonali, Singh RP, Singh N, et al. Transferrin liposomes of docetaxel for brain-targeted cancer applications: formulation and brain theranostics. Drug Deliv 2016; 23: 1261–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen ZL, Huang M, Wang XR, et al. Transferrin-modified liposome promotes alfa-mangostin to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology, Biol Med 2016; 12: 421–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.