Abstract

Background & Aims

Frailty is predictive of death in patients with cirrhosis, but studies to date have been limited to assessments at a single time point. We aimed to evaluate changes in frailty over time (ΔLFI) and its association with death/delisting for sickness.

Methods

Adults with cirrhosis listed for liver transplantation without hepatocellular carcinoma at 8 U.S. centers underwent ambulatory longitudinal frailty testing with the Liver Frailty Index (LFI). We used multilevel linear mixed effects regression to model and predict ΔLFI per 3 months based on age, gender, MELDNa, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) and categorize patients by frailty trajectories. Competing risk regression evaluated the subhazard ratio (sHR) of baseline LFI and predicted ΔLFI on death/delisting, with transplantation as the competing risk.

Results

We analyzed 2,851 visits from 1,093 outpatients with cirrhosis. Patients with severe frailty worsening had worse baseline LFI and were more likely to have NAFLD, diabetes, or dialysis-dependence. After a median follow-up of 11 months, 223 (20%) of the overall cohort died/were delisted for sickness. The cumulative incidence of death/delisting increased by worsening ΔLFI group. In competing risk regression adjusted for baseline LFI, age, height, MELDNa, and albumin, a 0.1 unit change in ΔLFI per 3 months was associated with a 2.04-fold increased risk of death/delisting (95% CI, 1.35–3.09).

Conclusion

Changes in frailty were significantly associated with death/delisting independent of baseline frailty and MELDNa. Notably, patients who experienced improvements in frailty over time had a lower risk of death/delisting than those who experienced worsening frailty. Our data support the longitudinal measurement of frailty, using the LFI, in patients with cirrhosis and lay the foundation for interventional work aimed at reversing frailty.

Keywords: malnutrition, portal hypertension, physical function, quality of life

Lay summary

Frailty, as measured at a single time point, is predictive of death in patients with cirrhosis, but whether change in frailty over time is associated with death is unknown. In an 8-center study of over 1,000 patients with cirrhosis who underwent testing of frailty, we demonstrate that patients changes in frailty are strongly linked with mortality, regardless of baseline frailty and liver disease severity. Notably, patients who experienced improvements in frailty over time had a lower risk of death/delisting than those who experienced worsening frailty. Our data support the longitudinal measurement of frailty, using the LFI, in patients with cirrhosis and lay the foundation for interventional work aimed at reversing frailty.

INTRODUCTION

The life of a patient with cirrhosis is characterized not only by the ongoing, chronic effects of hepatic synthetic dysfunction, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy but also by intermittent, catastrophic events such as acute variceal hemorrhage or spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Both these chronic and acute factors erode the patient’s physiologic reserve, ultimately manifesting in the clinical phenotype of “frail” commonly described in patients with cirrhosis. 1−4 We have previously demonstrated that the frail phenotype can be operationalized in the clinical and research hepatology settings using the performance-based Liver Frailty Index (LFI). [1] Consisting of grip strength, chair stands, and balance testing, the LFI can predict mortality among patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation above and beyond traditional metrics of liver disease severity (such as the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELDNa) score or the presence of ascites / hepatic encephalopathy[2]) as well as traditional metrics of mortality (such as age and body mass index[3,4]).

To date, studies evaluating the association between frailty and mortality in patients with cirrhosis have been limited to assessments of frailty at a single time point. However, data from geriatric populations – in whom the construct of frailty originated – have suggested that changes in frailty (and physical function, a related construct) are informative of outcomes. [5–7] Therefore, we aimed to describe trajectories of frailty (ΔLFI) among patients with cirrhosis and evaluate its association with mortality.

METHODS

Patients

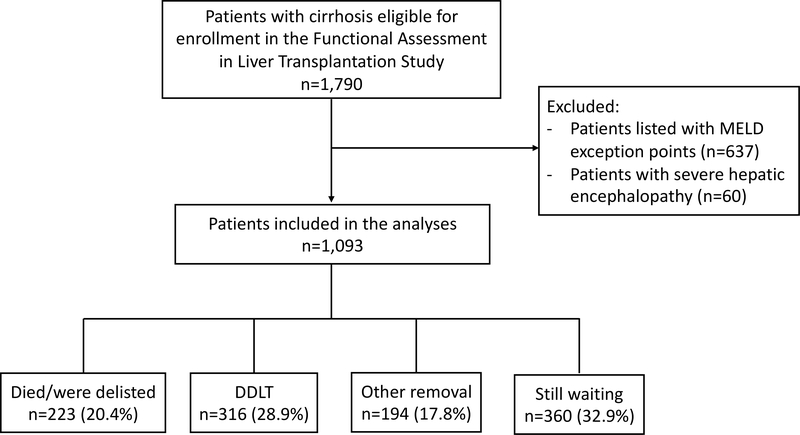

This study included data from 8 liver transplant centers in the United States from the Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) Study: University of California, San Francisco (n=830), Baylor University Medical Center (n=60), Columbia University Irving Medical Center (n=54), Duke University (n=41), University of Pittsburgh (n=35), Loma Linda University (n=35), University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (n=24), Northwestern (n=14). Patients were eligible to enroll in the FrAILT Study if they met the following criteria: 1) had cirrhosis, 2) were listed or eligible for listing for liver transplantation, 3) seen as an outpatient for clinical care. Excluded from our analyses were patients who were listed with MELDNa exception points, as the time that these patients spend on the waitlist are not dependent on their native liver disease function. A flow chart of the study population is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population. (Abbreviations: DDLT, deceased donor liver transplantation; MELD, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease)

Study procedures

All data were collected prospectively. At enrollment and every subsequent ambulatory clinic visit, all patients underwent measurement of frailty using:

Grip strength[8]: the average of three trials, measured in the subject’s dominant hand using a hand dynamometer;

Timed chair stands[9]: measured as the number of seconds it takes to do five chair stands with the subject’s arms folded across the chest;

Balance testing[9]: measured as the number of seconds that the subject can balance in three positions (feet placed side-to-side, semi-tandem, and tandem) for a maximum of 10 seconds each.

These three tests were administered by trained study personnel. With these three individual tests of frailty, the Liver Frailty Index was calculated using the following equation3 (calculator available at: http://liverfrailtyindex.ucsf.edu):

This equation produces a continuous score in which patients with a higher Liver Frailty Index are considered more frail. In order to maximize participation and follow-up in this study, all patients were tested as part of their routine clinic visit, which was determined at the discretion of the treating hepatologist at each individual center. Patients were only assessed during ambulatory clinic visits and not during hospitalizations. If patients were hospitalized during their time in the study, they remained in the study and were next assessed at a subsequent clinic visit. Patients enrolled in the study were treated under standard-of-care at each center, independent of their frailty assessment. Patients enrolled in the study were treated under standard-of-care at each center, independent of their frailty assessment.

Data regarding demographics were collected from the clinic visit note from the same day as the objective frailty measurement. A diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, or coronary artery disease was recorded if reported in their electronic health record. Laboratory data to calculate the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELDNa) score was obtained from the medical record, which is required to be drawn at set minimum intervals as part of maintaining active listing for liver transplantation. Presence of ascites was ascertained from the hepatologists’ recorded physical exam or the management plan associated with the clinic visit that occurred on the same day at the assessment of frailty. Ascites was categorized as “absent” if ascites was not present on physical exam or “present” if ascites was present on exam and/or the patient was noted to be undergoing large volume paracenteses. Hepatic encephalopathy was determined at the baseline study visit from the time to complete the Numbers Connection Test A performed at the time of the frailty measurement and categorized as “present” if the patient took ≥45 seconds to complete the task.[10]

Statistical analysis

Baseline demographics were presented as medians [interquartile ranges (IQR)] for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. The primary outcome was waitlist mortality, defined as the combined outcome of death or delisting for being too sick for liver transplantation. Follow up time for those who did not achieve a terminal waitlist event was censored on January 30, 2019. We used multilevel mixed-effects linear regression to model longitudinal data from each clinic visit and predict ΔLFI per 3 months. Each participant could contribute multiple observations. We structured the model with two levels (participant and visit), nesting the longitudinal visit-level observations within the participant to address correlation. Baseline age, gender, MELDNa, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy were modeled as fixed effects. These characteristics were selected a priori and included in the multivariable model, regardless of statistical significance, given their biologically plausible association with frailty. Participant and follow-up time were modeled as random effects to allow for random intercepts and random slopes, respectively. The random intercepts and slopes were allowed to be correlated to accommodate, for example, those with greater baseline frailty worsening more quickly. We addressed varying time between LFI observations by including the actual time of the measurement (from baseline to each LFI assessment) as a predictor in the mixed effects model. This allowed the model to account for differences in timing of LFI measurements. From the multivariable mixed effects model, we calculated the predicted intercept (baseline LFI) and slope (ΔLFI) per 3 months for each participant to facilitate clinical interpretation of the data and for the purposes of visual presentation. Higher positive ΔLFI values reflected more rapid frailty progression, positive ΔLFI values closer to 0 reflected slower frailty progression, and negative ΔLFI values reflected improving frailty.

We categorized ΔLFI into four categories: improved, stable, moderate worsening, and severe worsening. These categories were initially based on quartiles of ΔLFI slopes in this cohort. However, to create a homogenous and clinically meaningful reference group, the cutoff for the lowest quartile was set to ΔLFI of 0, such that, participants with improving LFI (negative slope) were not combined with participants with worsening LFI (positive slope). Participants who were initially classified in the lowest quartile of ΔLFI but had a positive slope were classified in the “stable” group. Baseline characteristics were compared by ΔLFI categories using the Kruskal-Wallis and chi-square tests. To evaluate the impact of baseline LFI and predicted ΔLFI on risk of waitlist mortality, we estimated the cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality within 3-, 6-, and 12-months of study entry by ΔLFI category. Then we modeled the cumulative incidence function with Fine and Gray competing risk regressions to estimate the risk of waitlist mortality associated with each variable.[11] Risk estimates were described as subhazard ratios (sHR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). In these competing risk models, waitlist mortality was defined as a death or delisting; deceased donor liver transplant was treated as the competing risk. Patients who underwent living donor liver transplantation were censored on the day of their liver transplant as their removal from the waitlist was a function of the availability of a living donor (a random event) rather than their natural liver disease progression. Patients who were removed for reasons other than being too sick (i.e. for social reasons) were also censored on the day of their removal from the waitlist. For the multivariable regression, all variables associated with waitlist mortality with a p-value of <0.1 in univariable analysis were evaluated for inclusion in the final multivariable model. Backwards elimination was then performed to derive the final multivariable model which included only variables associated with a p-value <0.05 and MELDNa due to the biologically plausible association with waitlist mortality. Interactions between baseline LFI and ΔLFI were assessed but did not achieve statistical significance. To determine if the MELDNa sHR changed significantly after adjusting for LFI, differences in MELDNa regression coefficients were compared between models with and without LFI and ΔLFI using bootstrap methods (100 replications).

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (v9.4, SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and Stata (v14, StataCorp, College Station, TX). The Institutional Review Boards at each of the participating sites approved this study. All participants provided signed informed consent to participate in this study.

RESULTS

A total of 1,093 patients with cirrhosis were included in this study.

Characteristics of the entire patient population (Table 1)

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 1,093 patients with cirrhosis included in this study categorized by their frailty trajectory.

| Characteristics* | All n=1,093 | By Frailty Trajectory | p-value† | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severe worsening n=284 (26%) | Moderate worsening n=252 (23%) | Stable n=387 (35%) | Improved n=170 (16%) | ||||

| Age, years | 58 (49–63) | 58 (51–63) | 58 (50–62) | 57 (48–63) | 58 (50–63) | 0.75 | |

| Female | 42% | 45% | 42% | 41% | 39% | 0.50 | |

| Race/Ethnicity | Non-Hispanic White | 61% | 64% | 63% | 60% | 57% | 0.40 |

| Black | 4% | 3% | 6% | 4% | 4% | ||

| Hispanic | 23% | 23% | 21% | 25% | 24% | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 5% | 3% | 3% | 5% | 8% | ||

| Other | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% | 7% | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28 (25–33) | 28 (25–33) | 29 (25–33) | 28 (25–32) | 28 (25–32) | 0.72 | |

| Etiology of liver disease | Chronic hepatitis C | 27% | 28% | 22% | 27% | 35% | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | 26% | 26% | 26% | 24% | 31% | ||

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 17% | 21% | 25% | 15% | 7% | ||

| Autoimmune/cholestatic | 16% | 14% | 12% | 19% | 17% | ||

| Other | 13% | 11% | 14% | 15% | 10% | ||

| Hypertension | 38% | 37% | 39% | 38% | 37% | 0.98 | |

| Diabetes | 30% | 39% | 33% | 24% | 24% | <0.001 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 5% | 5% | 6% | 5% | 4% | 0.60 | |

| MELDNa | 18 (15–23) | 18 (14–23) | 20 (16–24) | 19 (15–23) | 17 (14–20) | <0.001 | |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 2.6 (1.6–4.2) | 2.4 (1.5–3.8) | 2.8 (1.7–4.8) | 2.8 (1.7–4.5) | 2.4 (1.6–3.4) | 0.007 | |

| Creatinine, mg/dL‡ | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) | 0.14 | |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.0 (2.6–3.5) | 3.0 (2.6–3.4) | 3.1 (2.8–3.6) | 3.0 (2.6–3.4) | 3.1 (2.7–3.5) | 0.03 | |

| Dialysis | 5% | 8% | 7% | 4% | 1% | 0.008 | |

| Ascites | 34% | 36% | 35% | 34% | 28% | 0.68 | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 41% | 24% | 21% | 17% | 17% | 0.20 | |

| Liver Frailty Index at first assessment | 3.9 (3.5–4.5) | 4.6 (3.9–5.2) | 4.2 (3.9–4.5) | 3.6 (3.3–4.0) | 3.6 (3.1–4.0) | <0.001 | |

| Liver Frailty Index at last assessment | 4.0 (3.4–4.6) | 5.0 (4.6–5.5) | 4.2 (4.0–4.5) | 3.6 (3.3–3.9) | 3.1 (2.6–3.5) | <0.001 | |

| Absolute change in Liver Frailty Index from first to last assessment | 0.0 (−0.3–0.4) | 0.7 (0.2–1.2) | 0.2 (−0.1–0.4) | −0.0 (−0.3–0.2) | −0.5 (−0.8–0.2) | <0.001 | |

| Absolute change in Liver Frailty Index per 3 months | 0.01 (−0.09–0.14) | 0.15 (0.05–0.39) | 0.05 (−0.03–0.18) | −0.01 (−0.17–0.06) | −0.07 (−0.17–0.03) | <0.001 | |

Median (interquartile range) or %

Kruskal-Wallis tests were used for continuous variables and chi square tests were used for categorical variables to compare the differences between the groups.

Among those who were not on dialysis

Baseline characteristics of the cohort are shown in Table 1. Median age of the patients in our cohort was 58 years. Forty-two percent were female, 61% were non-Hispanic White, 27% had chronic hepatitis C, 26% had alcoholic liver disease, 17% had non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. With respect to major co-morbidities, 38% had hypertension, 30% had diabetes, and 5% had coronary artery disease. Median MELDNa was 18, reflecting the outpatient status of the patients in our cohort; 5% were on dialysis. Ascites was present in 41%, hepatic encephalopathy in 33%. Median (IQR) LFI at enrollment was 3.9 (3.5–4.5).

At a median (IQR) follow-up from enrollment to waitlist outcome of 10.6 months (4.6–20.8), 219 (20%) died or were delisted for being too sick for transplant, 29% underwent deceased donor liver transplantation, 18% were removed for reasons other than being too sick for transplant; the remaining 33% were censored from the analysis at the time of last follow-up.

Characteristics of patients by trajectories of frailty (Table 1)

We analyzed a total of 2,851 visits from the 1,093 patients included in this study. The median (IQR) number of visits per patient was 2 (1–3). The median (IQR) time between assessments (among those with multiple LFI assessments) was 126 days (98–182). Using mixed effects models, we estimated a trajectory of the Liver Frailty Index per 3 months (ΔLFI) for each patient based on age, gender, MELDNa, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy and then categorized patients by ΔLFI trajectories: severe worsening (16%), moderate worsening (35%), stable (23%), and improved frailty (26%).

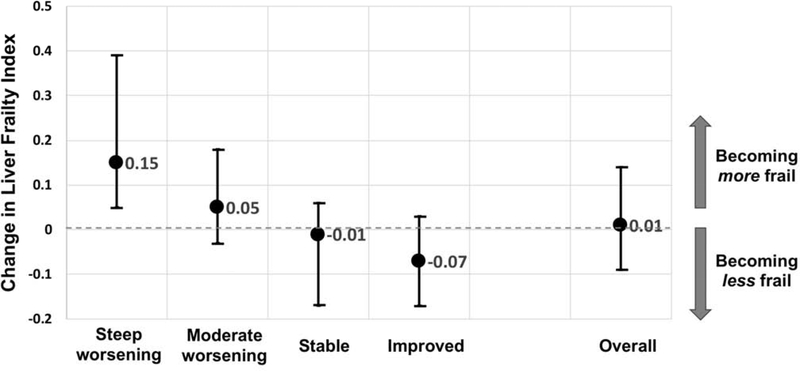

Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the cohort by ΔLFI trajectories. Comparing baseline characteristics by ΔLFI trajectories, patients with NASH, diabetes, or on hemodialysis were significantly more likely to experience worsening of frailty over time. Baseline median MELDNa score ranged from 17 to 20 among the 4 categories (p<0.001). Other baseline characteristics – including age, % women, racial/ethnic make-up, % with hypertension or with coronary artery disease, body mass index, % with ascites or hepatic encephalopathy – were similar by ΔLFI trajectory. LFI at first assessment was significantly higher among those with severe worsening compared to those who improved their frailty (p<0.001) as was LFI at last assessment. Median (IQR) changes in actual LFI per 3 months are shown graphically in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Change in the Liver Frailty Index scores per 3 months by ΔLFI trajectory group (medians and interquartile ranges).

The median (IQR) number of visits differed significantly by ΔLFI group: 2 (1–4) for the severe worsening group, 1 (1–2) for the slight worsening group, 2 (1–2) for the stable group, 4 (3–6) for the improved group. The median (IQR) number of days between visits (among those with >1 LFI assessment) was 112 days (91–179) for steep worsening, 112 days (91–161) for moderate worsening, 119 days (97–175) for stable and 168 days (116–210) for improved (p<0.001). Participants who died/delisted for too sick versus other waitlist outcomes had a similar median number of visits (2 (1–3) vs 2 (1–4), p=0.55).

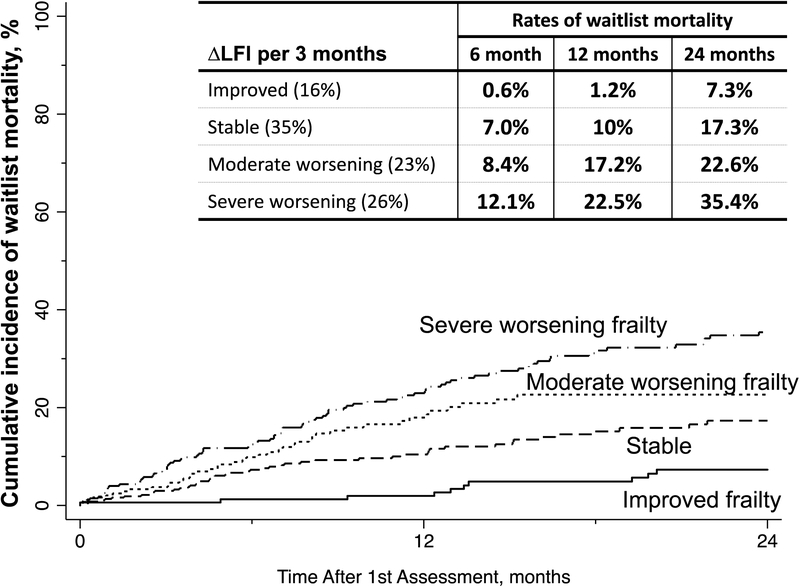

The association between changes in frailty and waitlist mortality

The cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality is displayed in Figure 3. By worsening ΔLFI trajectory, observed rates of waitlist mortality at 6 months were 0.6%, 7%, 8.4%, and 12.1%; at 12 months were 1.2%, 10%, 17.2%, and 22.5%; and at 24 months were 7.3%, 17.3%, 22.6%, and 35.4%.

Figure 3.

Observed cumulative incidence of waitlist mortality by categories of ΔLFI per 3 months.

We then sought to precisely quantify the association between ΔLFI and waitlist mortality and understand this association independent of baseline frailty and MELDNa, both of which are well-established predictors of mortality (Table 2). In univariable competing risk regression, each 0.1 unit change in ΔLFI per 3 months was associated with a 3.91-fold increased risk of waitlist mortality (95% CI, 2.80–5.46). As expected, both baseline LFI (HR per 0.1 unit increase, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.06–1.09) and MELDNa (HR per 5 unit increase, 1.26; 95% CI, 1.12–1.42) were also associated with an increased risk of waitlist mortality. In multivariable analysis, adjusting for baseline LFI and baseline MELDNa (along with age, albumin, and height), ΔLFI remained significantly associated with waitlist mortality (sHR per 0.1 unit worsening every 3 months, 2.04; 95% CI 1.35–3.09). In a sensitivity analysis evaluating the association between ΔLFI and the outcome of death alone (without delisting), the subhazard ratio associated with ΔLFI was 2.10 (95% CI, 1.04–4.18), which was similar the subhazard ratio observed for the combined outcome of death plus delisting for being too sick for transplant.

Table 2.

Univariable and step-wise additive multivariable models to assess associations between co-variables with waitlist mortality using competing risks models (with deceased donor liver transplant as the competing risk) for the primary predictors of ΔLFI (per 0.1 unit worsening every 3 months).

| Subhazard Ratios (95% CI) p-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable analysis | Stepwise multivariable analyses | ||

| ΔLFI, per 0.1 unit worsening every 3 months | 3.91 (2.80–5.46) <0.001 |

1.85 (1.22–2.82) 0.004 |

2.04 (1.35–3.09) 0.001 |

| Baseline LFI, per each 0.1 unit worsening | 1.07 (1.06–1.09) <0.001 |

1.08 (1.06–1.11) <0.001 |

1.07 (1.05–1.10) <0.001 |

| MELDNa, per each 5 unit increase | 1.26 (1.12–1.42) <0.001 |

1.11 (0.98–1.27) 0.11 |

|

Adjusted for the variables that were associated with a p<0.05: age, albumin, and height. Other variables that were evaluated for inclusion in the final models but were not associated with waitlist mortality with a p<0.05 were hypertension, diabetes, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Having observed a relatively high magnitude of change in the sHR associated with ΔLFI from the univariable to the multivariable analyses (3.91 2.04), we performed additional analyses using stepwise forward regression to better understand which co-variate (baseline LFI or MELDNa) most strongly influenced the relationship between ΔLFI and waitlist mortality. In forward stepwise regression (adjusted for age and height), the addition of baseline LFI was associated with a decrease in the sHR from 3.91 to 1.85, which remained relatively stable (2.04) after addition of MELDNa (Table 2). There was no significant interaction between baseline LFI and ΔLFI (p=0.34).

DISCUSSION

Over the last decade, frailty has been recognized as a critical determinant of outcomes in patients with cirrhosis.1,2,4,6,16,17 But few studies have evaluated the clinical importance of changes in frailty in this population. To address this knowledge gap, we used longitudinal data from over 1,000 patients enrolled in the multi-center FrAILT Study to study trajectories of frailty in patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. We observed that worsening of frailty was associated with a significantly increased risk of waitlist mortality, independent of baseline frailty and baseline MELDNa. This association occurred in a dose-dependent manner: compared to those who displayed relatively stable frailty, rates of waitlist mortality increased in a step-wise fashion among those with moderate or severe worsening of frailty. Specifically, compared to a patient who was stable, a patient who experienced severe worsening of their frailty experienced over double the rate of waitlist mortality within one year (10% versus 23%).

The fact that a patient with worsening frailty experiences a higher risk of death should come as no surprise to any clinician. While our analyses offer a precise quantification of this risk, we believe that the true value of our data to the community lie in demonstrating the clinical significance of improving one’s frailty status, which has not previously been studied. Compared to those who displayed a relatively stable frailty trajectory, patients who displayed improvement in their frailty scores experienced rates of waitlist mortality that were a fraction of those experienced by all other trajectories (from the severe worsening to the stable groups). Although this was an observational study, these data offer crucial evidence to suggest the impact that interventions targeting frailty might have on reducing mortality in this population.

It is worth noting the key differences in the baseline characteristics of the patients who improved their frailty scores in this cohort. Patients who experienced improvement in their frailty scores were less likely to have NAFLD as their cirrhosis etiology, diabetes, or dialysis-dependence – factors that would be expected to be associated with more frailty. Perhaps the most notable difference, however, was that patients who experienced improvement in their frailty trajectories had substantially lower baseline Liver Frailty Index scores (indicating less frailty). The association between frailty trajectory and waitlist mortality remained significant even after adjustment for baseline Liver Frailty Index as a potential confounder. These data serve as additional evidence supporting objective frailty measurement in clinical practice—not only is a single assessment of frailty predictive of waitlist mortality but it also helps to identify those who are most vulnerable to rapid functional decline—which exacerbates their risk of death.

Beyond indicating a higher risk of waitlist mortality, a worsening Liver Frailty Index may provide clinicians with important insight into the lived experience of a patient with cirrhosis. While the index components—grip strength, chair stands, and balance—represent measures of malnutrition, lower extremity function, and neurocognitive function, respectively, [1] we have found that the Liver Frailty Index is strongly associated with concurrent and subsequent disability.[12] Furthermore, patients with higher degrees of frailty (as assessed by the Liver Frailty Index) experience significantly higher rates of symptom burden (as assessed by the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale) [unpublished data]. Although we did not directly measure quality of life in this study, these data associating the Liver Frailty Index with patient-reported outcomes suggests that worsening frailty scores indicates worsening quality of life.

In this study, frailty assessments were performed solely in the outpatient setting. We designed the study in this way to lay the foundation for future work aimed at developing interventions targeted towards frailty at a time when the patient would be able to embark upon interventions (e.g., not acutely ill). We acknowledge that acute clinical events occurring in between assessments, such as hospitalizations, may have accelerated progression of frailty particularly in the severe worsening group. However, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the independent association between changes in frailty and waitlist mortality, not the mechanism behind the varying frailty trajectories, so such information would not change the clinical interpretation of our results. Furthermore, it is very difficult—in both clinical and research settings—to account for hospitalizations when interpreting a patient’s clinical status or interpreting research results. It is unlikely that all hospitalizations exert the same effect on frailty for each patient; the indication for hospitalization likely matters but is very difficult to ascertain accurately and consistently. It is this reason that we believe that longitudinal assessment of frailty is valuable—it represents the end manifestation of the effects of all insults to the patients, whether they be the insidious effects of portal hypertensive complications or the catastrophic effects of an acute hospitalization.

We acknowledge the following limitations to this study. Although we have previously demonstrated that the Liver Frailty Index is both reliable and reproducible,[13] there is some degree of natural variability from one assessment to the next that may not accurately reflect changes in risk of waitlist mortality. Our use of mixed effects modeling was intended to account for this random variation in the Liver Frailty Index and minimize its impact on the subhazard of waitlist mortality. Second, each center was allowed to utilize its own protocol for listing and work-up of patients for liver transplantation, including using the Liver Frailty Index, if desired. While this enhances the generalizability of our findings to real-life clinical practice, it may have introduced selection bias. However, none of the centers participating in the study (including UCSF) has developed specific guidelines for listing or de-listing of patients for liver transplantation—such decisions are made on a case-by-case basis. In addition, a sensitivity analysis evaluating the outcome of death alone (without the outcome of “delisting for sickness” that may be more strongly biased by the use of the Liver Frailty Index) demonstrated a similar subhazard ratio associated with ΔLFI. Lastly, the time between visits from one patient to the next was not standardized – we only assessed frailty when patients presented in clinic for their follow-up visit visits. This was intentional, as we believed that this would reduce study burden on patients and maximize enrollment, as well as enhance the applicability of our results to real-life clinical practice. Although the number of and timing between visits varied by participant, linear mixed effects models can accommodate unequal numbers and timing of measurements and offer protection against bias due to many forms of association between the timing and the outcomes and exposures being measured.[14] Furthermore, a sensitivity analysis utilizing a time-dependent modeling strategy to generate risk estimates did not change the highly significant association that we observed between baseline LFI or change in LFI and waitlist mortality. Lastly, our model only describes linear trends in ΔLFI assessments. However, a sensitivity analysis that allowed for person-specific non-linearity actually demonstrated worse model fit (by Bayesian information criterion).

Despite these limitations, our study provides new insights into the management of patients with cirrhosis, particularly those awaiting liver transplantation. To date, the work from our FrAILT Study has emphasized the importance of a one-time assessment in frailty in prediction and quantification of excess mortality risk. But if a patient starts off frail today, is there anything that can be done to mitigate this risk? The analyses that we present in this manuscript demonstrate that those who improve over time – regardless of their baseline frailty status (as well as other metrics of liver disease severity) – experienced lower mortality rates. If we believe that frailty is intervenable – and in our study, 16% experienced improvement in their Liver Frailty Index scores – then might we be able to actively reduce mortality? While our analyses from this observational cohort do not prove causation, these data lay the essential scientific foundation for the development of interventions aimed at reversing frailty.

Highlights.

In patients with cirrhosis, changes in frailty were significantly associated with death/delisting independent of baseline frailty and MELDNa.

Patients with cirrhosis who experienced improvements in frailty over time had a lower risk of death/delisting than those who experienced worsening frailty.

Our data support the longitudinal measurement of frailty, using the Liver Frailty Index, in patients with cirrhosis and lay the foundation for interventional work aimed at reversing frailty.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was funded by NIH K23AG048337 (Lai), NIH R01AG059183 (Lai), NIH F32AG053025 (Haugen), NIH P30DK026743 (Lai, Dodge), NIH K24DK101828 (Segev). These funding agencies played no role in the analysis of the data or the preparation of this manuscript.

List of abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- IQR

interquartile range

- LFI

Liver Frailty Index

- MELDNa

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease-Sodium

- sHR

subhazard ratio

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by Journal of Hepatology.

Writing Assistance: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Lai JC, Covinsky KE, Dodge JL, Boscardin WJ, Segev DL, Roberts JP, et al. Development of a novel frailty index to predict mortality in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2017;66:564–74. doi: 10.1002/hep.29219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Lai JC, Rahimi RS, Verna EC, Kappus MR, Dunn MA, McAdams-DeMarco M, et al. Frailty Associated With Waitlist Mortality Independent of Ascites and Hepatic Encephalopathy in a Multicenter Study. Gastroenterology 2019. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Haugen CE, McAdams-DeMarco M, Holscher CM, Ying H, Gurakar AO, Garonzik-Wang J, et al. Multicenter Study of Age, Frailty, and Waitlist Mortality Among Liver Transplant Candidates. Ann Surg 2019:1–5. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Haugen CE, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Verna EC, Rahimi RS, Kappus MR, Dunn MA, et al. Body mass index, frailty, and waitlist mortality: From the Multi-center Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation (FrAILT) Study. JAMA Surg n.d. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Gill TM, Murphy TE, Gahbauer EA, Allore HG. The Course of Disability Before and After a Serious Fall Injury. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1780–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gill TM, Allore HG, Gahbauer EA, Murphy TE. Change in disability after hospitalization or restricted activity in older persons. JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association 2010;304:1919–28. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Stow D, Matthews FE, Hanratty B. Frailty trajectories to identify end of life: a longitudinal population-based study 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol a Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:146–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. Journal of Gerontology 1994;49:85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Weissenborn K, Rückert N, Hecker H, Manns MP. The number connection tests A and B: interindividual variability and use for the assessment of early hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 1998;28:646–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lai JC, Dodge JL, McCulloch CE, Covinsky KE, Singer JP. Frailty and the burden of concurrent and incident disability in patients with cirrhosis: A prospective cohort study [in press]. Hepatology Communications 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wang CW, Lebsack A, Chau S, Lai JC. The Range and Reproducibility of the Liver Frailty Index. Liver Transpl 2019;25:841–7. doi: 10.1002/lt.25449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Laird NM. Missing data in longitudinal studies. Statist Med 1988;7:305–15. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780070131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]