Abstract

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused dramatic changes in daily routines and health care utilization and delivery patterns in the United States. Understanding the influence of these changes and associated public health interventions on asthma care is important to determine effects on patient outcomes and identify measures that will ensure optimal future health care delivery.

Objective

We sought to identify changes in pediatric asthma-related health care utilization, respiratory viral testing, and air pollution during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

For the time period January 17 to May 17, 2015 to 2020, asthma-related encounters and weekly summaries of respiratory viral testing data were extracted from Children's Hospital of Philadelphia electronic health records, and pollution data for 4 criteria air pollutants were extracted from AirNow. Changes in encounter characteristics, viral testing patterns, and air pollution before and after Mar 17, 2020, the date public health interventions to limit viral transmission were enacted in Philadelphia, were assessed and compared with data from 2015 to 2019 as a historical reference.

Results

After March 17, 2020, in-person asthma encounters decreased by 87% (outpatient) and 84% (emergency + inpatient). Video telemedicine, which was not previously available, became the most highly used asthma encounter modality (61% of all visits), and telephone encounters increased by 19%. Concurrently, asthma-related systemic steroid prescriptions and frequency of rhinovirus test positivity decreased, although air pollution levels did not substantially change, compared with historical trends.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic in Philadelphia was accompanied by changes in pediatric asthma health care delivery patterns, including reduced admissions and systemic steroid prescriptions. Reduced rhinovirus infections may have contributed to these patterns.

Key words: Asthma, COVID-19, Pollution, Telemedicine, Respiratory virus

Abbreviations used: CHOP, Children's Hospital of Philadelphia; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; ED, Emergency department; EPA, Environmental Protection Agency; IFV-A, Influenza virus A; IFV-B, Influenza virus B; PM2.5, Particulate matter less than 2.5 microns; PM10, Particulate matter less than 10 microns; RSV, Respiratory syncytial virus; RV, Rhinovirus; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; VTM, Video telemedicine

What is already known about this topic? The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic caused dramatic changes to daily routines and health care delivery in the United States.

What does this article add to our knowledge? Coronavirus disease 2019 public health interventions were accompanied by a reduction in pediatric asthma encounters and systemic steroid prescriptions. Decreased rhinovirus infections may have contributed to this apparent reduction in asthma exacerbations, although changes in 4 criteria air pollutants were not significantly different than historical trends.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? Our findings reinforce the value of preventative measures for asthma control, especially those designed to limit transmission of respiratory viruses.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), an illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), arose in late 2019 and rapidly spread around the world. By June 2020, more than 9 million cases and 469,000 deaths had been reported worldwide, with 2.3 million cases and 122,000 deaths in the United States.1 In response to COVID-19,2 health care systems reoriented their delivery structures to prepare for a dramatic increase in COVID-19 cases while attempting to shield unaffected individuals from infection. Simultaneously, various local and national public health interventions designed to limit viral transmission were enacted. At Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), the first COVID-19 patient tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on March 17, 2020. On this date, all nonessential businesses in Philadelphia were prohibited from operating in person.3 Subsequently, the city enacted a stay-at-home order and a closure of schools, with the intent to limit physical interactions among people and prevent transmission of the virus. Concern arose among patients and their parents that visiting a hospital or doctor's office put them at increased risk for contracting COVID-19, resulting in deferral of many in-person well-child and routine follow-up care visits.4 , 5 For all these reasons, many health care systems, including CHOP, adopted video telemedicine (VTM).6

Asthma is one of the most common chronic childhood diseases, affecting 1 of 12 school-age children in the United States,7 with a higher prevalence in Philadelphia than the national mean.8 , 9 Pollution and respiratory virus exposure, in particular rhinovirus (RV),10 , 11 can worsen asthma symptoms and trigger exacerbations.12 For example, exposure to US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) criteria air pollutants, including particulate matter less than 2.5 microns (PM2.5), particulate matter less than 10 microns (PM10), ozone, and nitrogen dioxide (NO2), has been associated with increased asthma exacerbations13, 14, 15, 16 and increased risk of developing asthma.17 Viral respiratory infections are also associated with most pediatric asthma exacerbations,18 and people with asthma experience more severe, longer-lasting respiratory viral infections than people without asthma.19 Based on these findings, it was thought that people with asthma were at risk for worse COVID-19 outcomes,20 , 21 although subsequent observational studies have found mixed results in support of this hypothesis.22, 23, 24

The public health interventions adopted to slow down the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 have altered environmental exposure profiles, which also influence the risk of asthma exacerbations. Infection prevention measures, including wearing face masks, washing hands frequently, and social distancing as a result of stay-at-home orders and school closures, reduce person-to-person transmission of all respiratory viruses. The decrease in transportation and industrial activity resulting from COVID-19 restrictions has reduced the emission of primary air pollutants worldwide,25 , 26 and there is current interest in determining the extent to which these changes have affected asthma symptoms.27 In this study, we sought to describe the impact of COVID-19 public health measures on pediatric asthma-related health care utilization, respiratory virus testing in our emergency department (ED), and pollution levels in the greater Philadelphia area.

Methods

Study population

We extracted asthma patient encounter data corresponding to the time period January 17 to May 17 for the years 2015 to 2020 from the CHOP Care Network, which consists of 48 outpatient primary and specialty care clinical sites, 4 urgent care sites, 15 community hospital alliances, and a 557-bed quaternary care center in the greater Philadelphia area. Data from this network have previously been validated as a tool to assess regional disease trends.8 , 28 Asthma diagnosis was established on the basis of encounters having an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code J45.nn. Accuracy of this definition was confirmed via manual review of 100 patient charts.

Variable selection

For each encounter, its type (ie, inpatient, ED, outpatient, telephone, and VTM) and date were extracted, along with data on the patient's sex, race, ethnicity, date of birth, and payer type. Race was based on self- or parent/guardian selection of 1 of the following categories: “white,” “black,” “Asian or Pacific Islander,” or “Other.” Subjects without a race selection were coded as “Unknown.” Codified asthma-related drug prescription data for all outpatient asthma-related prescriptions, and for outpatient and inpatient systemic steroid prescriptions, were obtained from CHOP provider prescription records (see Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

Virology data

CHOP ED results for respiratory viral testing for adenovirus, influenza A virus (IFV-A), influenza B virus (IFV-B), parainfluenza 1, parainfluenza 2, parainfluenza 3, non–COVID-19 coronavirus, metapneumovirus, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), RV, and COVID-19 via PCR testing were extracted from CHOP's Respiratory Virus Prevalence database. Data for the number of positive test results and tests administered for each virus for the time period January 17 to May 17 during the years 2015 to 2020 were obtained. The number of positive test results for each virus was compared with (1) the total number of tests administered for that virus only and (2) the overall number of viral tests administered for all the viruses listed above.

Air pollution data

Hourly PM2.5, PM10, ozone, and NO2 measures obtained at EPA monitoring sites in Philadelphia for the time period January 17 to May 17 during the years 2015 to 2020 were extracted from AirNow, an air quality data management system that reports real-time and forecast air quality estimates.29 Because historical data were not available for all pollutants in AirNow, we also downloaded daily summary files for the time period January 17 to May 17 during the years 2015 to 2019 from Air Data, an EPA resource that provides quality-assured summary air pollution measures collected from outdoor regulatory monitors across the United States.30 In Philadelphia, the same monitoring sites transmitted data to AirNow and AirData.

Data analysis

Characteristics of encounters, viral test results, and pollutant levels from the 60-day period before and after March 17, 2020 were compared with those from the period 2015 to 2019. A paired Student t test was used to examine differences in systemic steroid prescription rates between patients before and after March 17. For both viral testing and pollution data, controlled interrupted time series regression models were created to identify statistically significant changes between the pre–and post–March 17 60-day time frames that differed in 2020 compared with the 2015 to 2019 historical time period. Significant differences between 2020 and historical data were determined on the basis of P values for regression coefficients corresponding to interaction terms of variables representing pre–and post–March 17 status, the year(s) in question, and/or days. For viral testing, 2-way ANOVA and mixed-effect analysis were additionally used to test for significant differences. To visualize pollution levels across Philadelphia during time periods of interest, we generated 100 m × 100 m grid raster layers using inverse-distance-squared weighted averaging of pollutant measures from the 5 nearest monitoring stations. Analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif) and R (R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).31 Results were summarized as percentage change.

Data availability

The epidemiologic data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/record/3981568).

Ethical and regulatory oversight

The CHOP Institutional Review Board reviewed our study and determined it did not meet the definition of Human Subjects research.

Results

Asthma health care utilization decreased and VTM encounters increased after COVID-19 public health interventions

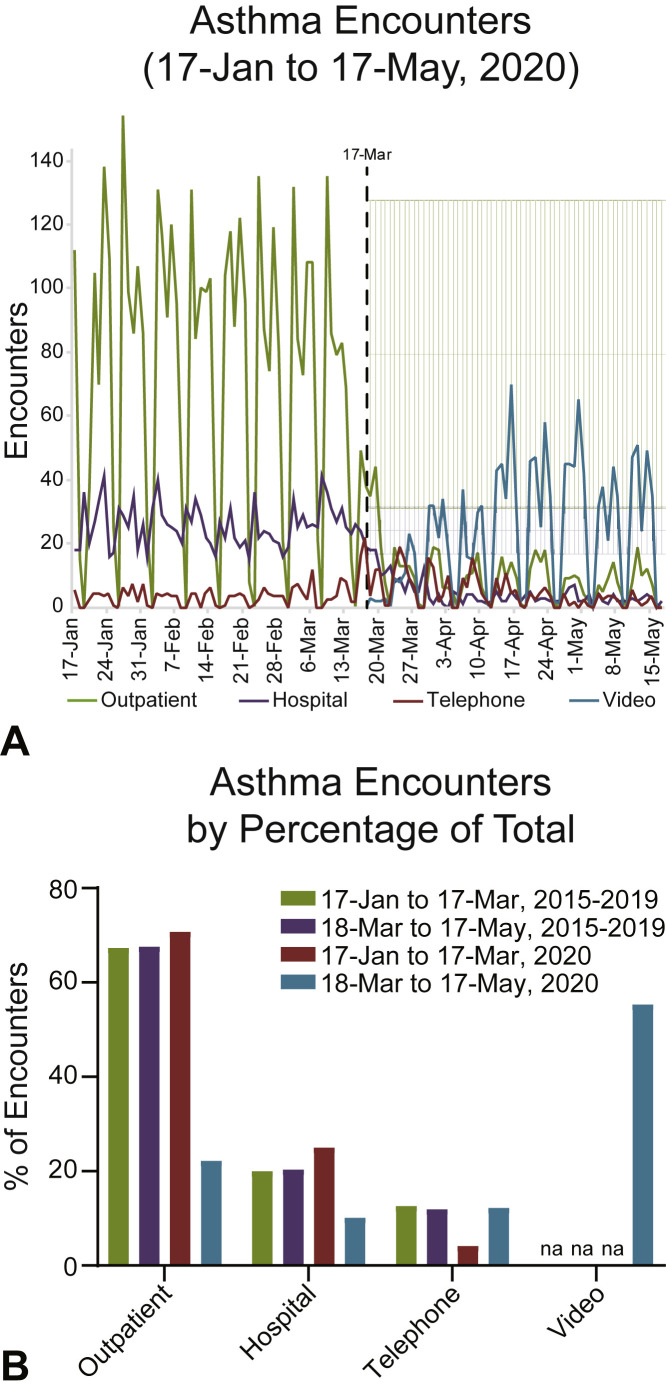

Before the public health measures enacted on March 17, 2020 in Philadelphia to limit COVID-19 spread, asthma health care visit numbers and encounter types at CHOP were similar to historical averages for the period 2015 to 2019. Overall, there was a 60% decrease in total daily asthma health care visits at CHOP when comparing the 60 days before and after March 17, 2020 (102.44 ± 48.9; range, 19-190, and 41.5 ± 25.7, range, 0-94, respectively) (Figure 1 ). Before March 17, 2020, the average numbers of outpatient and hospital (ED + inpatient) daily asthma encounters were 72.5 ± 46.2 (range, 0-154) and 25.7 ± 6.6 (range, 0-41), respectively. After March 17, 2020, the average number of daily outpatient encounters decreased by 87% to 9.2 ± 8.2 (range, 0-44), while hospital encounters decreased by 84% to 4.2 ± 3.8 (range, 0-18). Concurrently, asthma telephone encounters across the network increased by 19% from a daily average of 4.3 ± 4.2 (range, 0-24) to 5.1 ± 5.3 (range, 0-21) after March 17, 2020. VTM was not available before March 17, 2020, but was quickly adopted: asthma VTM encounters averaged 23.0 ± 19.9 per day (range, 0-70) and accounted for 61% of all encounters after March 17, 2020.

Figure 1.

Asthma encounters before and after public health interventions were enacted. (A) Daily asthma encounters from January 17 to May 17, 2020. Outpatient (primary + specialty care), telephone calls (telephone), hospital (ED + inpatient), and video (primary + specialty care) encounters are shown. Five-year historical averages (March 18 to May 17, 2015-2019) with 1 SD from the mean for outpatient (light green) or hospital (light purple) encounters shown. March 17 (black-dotted line) is the date Philadelphia prohibited the operation of nonessential businesses (effective 5 PM), and the date the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed at CHOP. (B) Historical and 2020 asthma encounters as a percentage of total. NA, Not applicable/available.

Demographic differences in asthma health care utilization and adoption of VTM

Per-patient demographic characteristics of our study population are presented in Table I . Although the total number of asthma encounters decreased after March 17, 2020, black patients represented a higher proportion of outpatient, hospital, or telephone care after this date compared with the preceding 60-day time period (54% vs 35%, 78% vs 65%, and 49% vs 24%, respectively). Patients with Medicaid coverage represented a higher proportion of outpatient or hospital care after March 17 compared with the pre–March 17, 2020 time period (55% vs 41% and 73% vs 63%, respectively). Of patients who engaged in VTM encounters in the post–March 17, 2020, time period, 26% were black and 30% had Medicaid coverage.

Table I.

Demographic characteristics of subjects with asthma by time period and encounter type

| Characteristic | Cohort (n) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-2019 |

January 17-March 17, 2020 (5,190) |

March 18-May 17, 2020 (2,273) |

|||||||||

| All (23,146) | Outpatient | Hospital | Telephone | Video | All | Outpatient | Hospital | Telephone | Video | All | |

| Sex, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Male | 13,644 (59) | 2,275 (59) | 826 (58) | 155 (62) | 0 (0) | 3,035 (58) | 253 (56) | 122 (50) | 169 (57) | 808 (59) | 1,294 (57) |

| Female | 9,502 (41) | 1,608 (41) | 603 (42) | 97 (38) | 0 (0) | 2,155 (42) | 196 (44) | 124 (50) | 129 (43) | 573 (41) | 979 (43) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||||||

| White | 9,536 (41) | 1,711 (44) | 251 (18) | 151 (60) | 0 (0) | 2,007 (39) | 131 (29) | 31 (13) | 103 (35) | 747 (54) | 979 (43) |

| Black | 9,678 (42) | 1,366 (35) | 927 (65) | 60 (24) | 0 (0) | 2,139 (41) | 242 (54) | 191 (78) | 145 (49) | 356 (26) | 880 (39) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 731 (3) | 168 (4) | 45 (3) | 6 (2) | 0 (0) | 204 (4) | 10 (2) | 3 (1) | 8 (3) | 37 (3) | 57 (3) |

| Other | 3,109 (13) | 606 (16) | 203 (14) | 34 (13) | 0 (0) | 805 (16) | 64 (14) | 21 (9) | 42 (14) | 234 (17) | 348 (15) |

| Unknown | 92 (0) | 32 (1) | 3 (0) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 35 (1) | 2 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (1) | 9 (0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 20,997 (91) | 3,426 (88) | 1,274 (89) | 223 (88) | 0 (0) | 4,579 (88) | 398 (89) | 228 (93) | 268 (90) | 1,217 (88) | 2,018 (89) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1,974 (9) | 419 (11) | 152 (11) | 27 (11) | 0 (0) | 568 (11) | 50 (11) | 18 (7) | 27 (9) | 149 (11) | 237 (10) |

| Unknown | 175 (1) | 38 (1) | 3 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 43 (1) | 1 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 15 (1) | 18 (1) |

| Birth year, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Before 2000 | 1,333 (6) | 22 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 0 (0) | 26 (1) | 9 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (1) | 8 (1) | 20 (1) |

| 2000-2004 | 4,096 (18) | 414 (11) | 124 (9) | 45 (18) | 0 (0) | 554 (11) | 68 (15) | 35 (14) | 64 (21) | 144 (10) | 295 (13) |

| 2005-2009 | 6,973 (30) | 979 (25) | 268 (19) | 57 (23) | 0 (0) | 1,231 (24) | 130 (29) | 52 (21) | 62 (21) | 312 (23) | 532 (23) |

| 2010-2014 | 8,057 (35) | 1,343 (35) | 492 (34) | 89 (35) | 0 (0) | 1,784 (34) | 141 (31) | 82 (33) | 91 (31) | 473 (34) | 753 (33) |

| 2015 or later | 2,687 (12) | 1,125 (29) | 544 (38) | 58 (23) | 0 (0) | 1,595 (31) | 101 (22) | 77 (31) | 77 (26) | 444 (32) | 673 (30) |

| Payer type, n (%) | |||||||||||

| Non-Medicaid | 13,676 (59) | 2,283 (59) | 532 (37) | 222 (88) | 0 (0) | 2,863 (55) | 201 (45) | 66 (27) | 254 (85) | 969 (70) | 1,446 (64) |

| Medicaid | 9,470 (41) | 1,600 (41) | 897 (63) | 30 (12) | 0 (0) | 2,327 (45) | 248 (55) | 180 (73) | 44 (15) | 412 (30) | 827 (36) |

Decreased prescriptions of systemic steroids after COVID-19 public health interventions

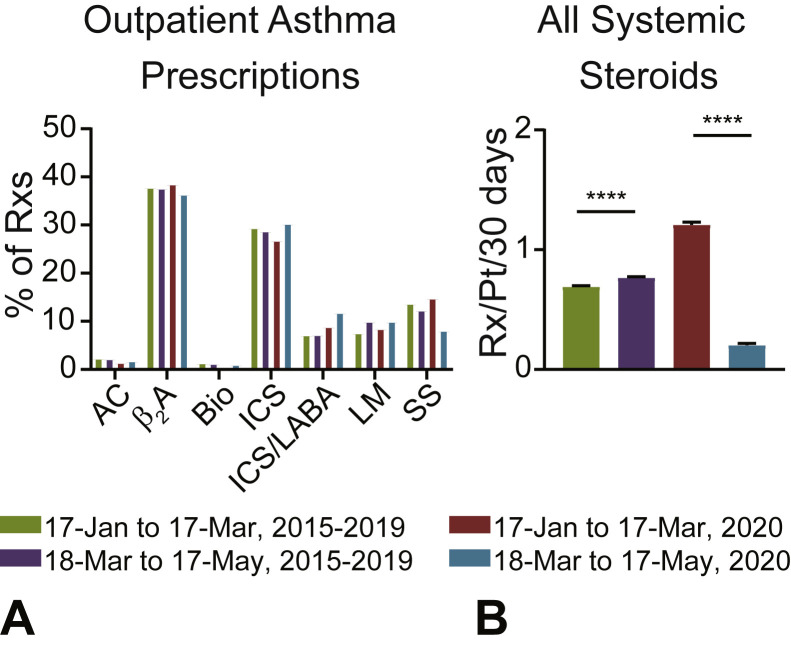

Comparison of pre–and post–March 17, 2020 CHOP prescription patterns found that the relative proportions of most outpatient asthma-related prescriptions were similar before and after introduction of COVID-19 public health interventions (Figure 2 , A). One exception was outpatient systemic steroid prescriptions, which were proportionally reduced compared with other asthma-related medications after the introduction of COVID-19 public health interventions (Figure 2, A). When limiting the comparison to patients who had at least 1 systemic steroid prescription from any primary asthma encounter (outpatient, emergency, or inpatient) between January 17 and May 17, 2020, there was a 83% decrease in systemic steroid prescriptions (Figure 2, B). Black patients and patients with Medicaid coverage represented the highest proportion of steroid prescription encounters between March 17 and May 17, 2020 (70% and 63%, respectively) (see Table E2 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

Figure 2.

Asthma prescriptions before and after public health interventions were enacted. (A) Outpatient asthma-related prescriptions by medication class as a percentage of total (AC, anticholinergic; β2A, β2 agonists; Bio, biologic; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; ICS + LABA, ICS with long-acting beta-agonist; LM, leukotriene modifier; Rxs, prescriptions; SS, systemic steroid). (B) Average number of systemic steroid prescriptions per patient per 30 days from any primary asthma encounter (outpatient, emergency, inpatient). Mean + SEM shown. Statistical comparison by paired Student t test. ∗∗∗∗P < .0001.

Decreased RV infections after COVID-19 public health interventions

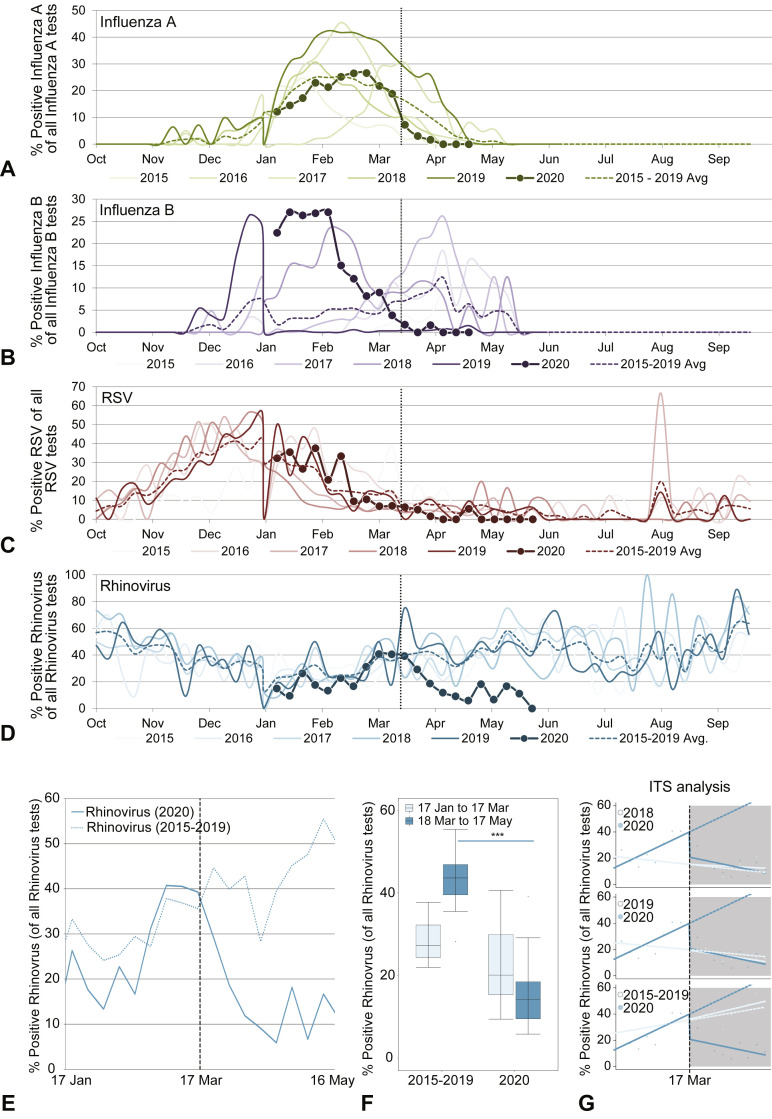

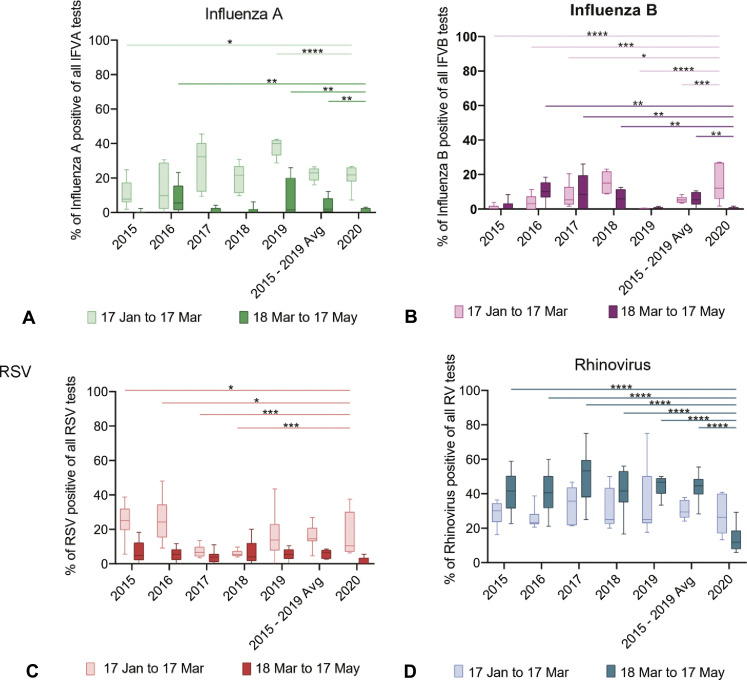

Given the importance of respiratory viral infections in asthma exacerbations, we sought to quantify the impact of COVID-19 public health interventions on respiratory viral testing. We focused on 4 key viruses; IFV-A, IFV-B, RSV, and RV. When examining viral data for the period 2019 to 2020, we noted variations in season onset and peak timing compared with historical trends. The IFV-A viral season had variable timing year-to-year and had neither an early nor a late season in the period 2019 to 2020 (Figure 3 , A). The IFV-B viral season had an earlier onset and peaked earlier in the period 2019 to 2020, as compared with recent previous years (Figure 3, B). Both the IFV-A and IFV-B seasons were waning by March 17, 2020. The RSV and RV seasonal patterns were similar in all years considered before March 17 (Figure 3, C and D). RSV was waning by March 17, 2020 (Figure 3, C), whereas the 2020 RV season was near its peak on March 17, 2020 (Figure 3, D). Controlled interrupted time series results found some significant changes when comparing 2020 data to previous years' data for all 3 of the 4 viruses (not for INF-A), though year-to-year variability was observed, consistent with variable timing of viral seasons (see Figure E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). For example, significant differences were identified for RSV in the period before March 17 though some previous years had higher rates of positive testing than in 2020, whereas others had lower (Figure E1, C, and Table II ). RV was the only virus with significantly decreased levels in the post–March 17, 2020, time period as compared with the same time period during previous years, when years were compared individually or as a 2015 to 2019 historical average (Figure E1, D, and Figure 3, E-G).

Figure 3.

Changes in viral respiratory testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Deidentified institutional ED virology testing results for the period 2015 to 2020 were accessed. (A-D) Time series plots comparing historical data (2015-2019) to the current year (2020) for rates of positive IFV-A (A), IFV-B (B), RV (C), and RSV (D) testing vs total tests for each virus. (E) For 2020, RV testing data from January 17 to March 17 and March 18 to May 17 were compared to averaged historical data from the same dates from 2015 to 2019. (F) Bar plots comparing the 2 time periods (January 17 to March 17 and March 18 to May 17) from the averaged historical time period (2015-2019) vs the current year (2020). (G) ITS plots comparing time series in 2018, 2019, and 2015 to 2019 averaged vs 2020. For each, the historical data are plotted in a lighter color. The dashed line after week 9 (March 17) is the predicted data based on the previous results, and the uninterrupted line is the actual data from 2020 (exact data also plotted as circles). Significance testing via ANOVA (F) and details in Table II for Figure 3, G. ITS, Interrupted time series.

Figure E1.

Effects of public health interventions designed to limit viral transmission on viral testing. Deidentified institutional ED virology testing results for the period 2015 to 2020 were accessed. (A-D) Bar plots of rates of positive viral testing (IFV-A, IFV-B, RSV, and RV, respectively) from January 17 to March 17 vs March 18 to May 17 in the period 2015 to 2019 (and the average of that range) vs 2020.

Table II.

ITS analysis of viral testing data from CHOP before and after COVID-19 public health interventions were enacted

| Years compared | IFV-A | IFV-B | RV | RSV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 vs 2020 | 0.93 (NS) | 0.025∗ | 0.0040† | 0.016∗ |

| 2016 vs 2020 | 0.52 (NS) | 0.0007‡ | 0.021∗ | 0.0008‡ |

| 2017 vs 2020 | 0.59 (NS) | 0.014∗ | 0.0006‡ | 0.0290∗ |

| 2018 vs 2020 | 0.89 (NS) | 0.037∗ | 0.0035† | 0.023∗ |

| 2019 vs 2020 | 0.81 (NS) | 0.011∗ | 0.011∗ | 0.0057† |

| 2015-2019 vs 2020 | 0.79 (NS) | 2.5 × 10−06‡ | 0.0074† | 0.14 (NS) |

ITS, Interrupted time series; NS, not significant.

P ≤ .05.

P ≤ .01.

P ≤ .001.

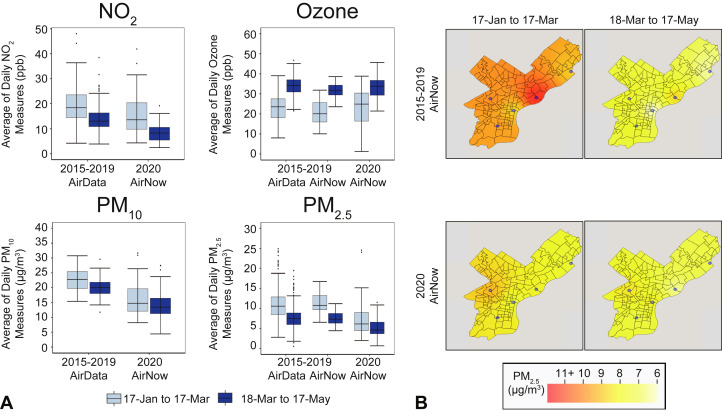

Levels of 4 criteria air pollutants in Philadelphia did not significantly change during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with historical data

Comparison of pre–and post–March 17, 2020 pollution levels (Table III ; Figure 4 , A) found that the daily average of PM2.5, PM10, and NO2 levels decreased by 29.0% (2.17 μg/m3), 18.2% (3.13 μg/m3), and 44.1% (6.75 ppb), respectively, whereas ozone levels increased by 43.4% (10.08 ppb). Historical data for the period 2015 to 2019 showed comparable changes pre–and post–Mar 17: AirNow estimates found that PM2.5 levels decreased by 34.2% (3.88 μg/m3) and ozone increased by 52.4% (10.9 ppb); AirData estimates found that PM2.5 levels decreased by 29.2% (3.15 μg/m3), PM10 by 11.6% (2.63 μg/m3), and NO2 by 28.5% (5.49 ppb), whereas ozone increased by 46.4% (10.69 ppb). Although some of these changes differed significantly across the full range of days (January 17 to May 17), year, and/or before and after the March 17 date, none of the changes were statistically significant compared with historical trends observed across the pre–and post–March 17 60-day time period (see Table E3 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org). Specifically, PM2.5 and PM10 had significantly decreased levels in 2020 compared with previous years during the days January 17 to May 17; PM2.5 significantly decreased after March 17 in all years whether using AirNow or AirData historical data (P < .05); ozone had significantly higher levels after March 17 and across all days whether using AirNow or AirData historical data (P < .001); and NO2 significantly decreased across days (P < .05) with no change before or after March 17 or by year. Figure 4, B, shows the raster of PM2.5 levels in Philadelphia for the 60-day pre–and post–March 17 periods along with the location of air monitoring stations that recorded PM2.5 measures.

Table III.

Mean measures of 4 criteria air pollutants in Philadelphia before and after COVID-19 public health interventions were enacted

| Air pollutant | AirData (2015-2019) |

AirNow (2015-2019) |

AirNow (2020) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 17 to March 17 | March 18 to May 17 | January 17 to March 17 | March 18 to May 17 | January 17 to March 17 | March 18 to May 17 | |

| NO2 (ppb) | 19.2 ± 6.8 | 13.7 ± 4.6 | NA | NA | 15.2 ± 7.6 | 8.5 ± 3.8 |

| Ozone (ppb) | 23.0 ± 6.5 | 33.7 ± 4.9 | 20.8 ± 5.8 | 31.7 ± 3.6 | 23.2 ± 8.5 | 33.2 ± 5.2 |

| PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 10.7 ± 3.5 | 7.6 ± 2.5 | 11.3 ± 2.4 | 7.4 ± 1.7 | 7.3 ± 4.3 | 5.2 ± 2.2 |

| PM10 (μg/m3) | 22.7 ± 3.4 | 20.1 ± 3.0 | NA | NA | 17.2 ± 7.7 | 14.0 ± 4.7 |

NA, Not available; ppb, parts per billion.

Values are mean ± SD.

Figure 4.

Levels of 4 criteria air pollutants in Philadelphia before and after COVID-19 public health interventions were enacted. (A) Boxplots of averages of daily NO2, ozone, PM10, and PM2.5 measures corresponding to years 2020 and 2015 to 2019 sourced from AirData and AirNow for the 60-day time period before and after March 17, the day in 2020 when COVID-19 public health interventions were enacted in Philadelphia. None of the changes across March 17 were significantly different in the year 2020 compared with historical years. (B) Philadelphia raster layer maps showing daily average PM2.5 levels before and after the COVID-19 public health interventions were enacted for the year 2020 and the average of years 2015 to 2019 using AirNow data. The blue circles denote available air monitoring sites. ppb, Parts per billion.

Discussion

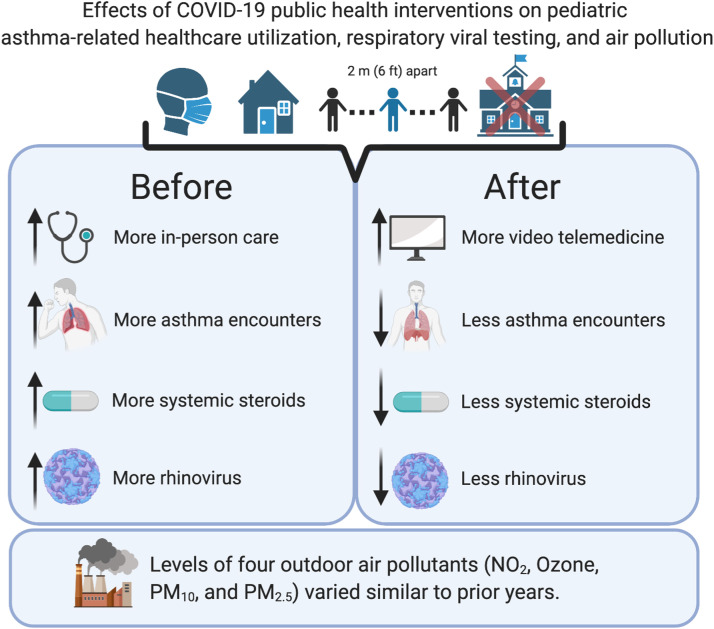

We found that public health interventions designed to limit SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the Philadelphia region were associated with increased VTM and decreased overall asthma encounters, systemic steroid prescriptions, and RV positivity in our ED (Figure 5 ). We previously noted an overall decrease in ED utilization at CHOP,32 a pattern consistent with that observed in other regions of the country, which included a shift away from in-person care and toward VTM-based care.33 Our observed decrease in the overall asthma disease burden is also consistent with national survey data.33

Figure 5.

Effects of public health interventions designed to limit viral transmission on asthma features. Public health interventions designed to limit viral transmission (masking, social distancing, school closures, etc) were associated with a restructuring of asthma care delivery including a reduction in in-person encounters and an increase in VTM-based care. Overall asthma encounters were reduced, as were systemic steroid prescriptions. Changes in RV infections, but not pollution levels, may have contributed to these trends.

After March 17, 2020, VTM became the most used asthma encounter modality at CHOP, enabling patients with asthma to access care while adhering to stay-at-home guidelines. Previous studies have demonstrated the utility of VTM to facilitate care delivery to underserved rural populations and as a viable substitute for both routine and acute in-person asthma care visits.34 , 35 However, the rapid introduction of VTM across the country represents a new, and as such, understudied care model. Black children accounted for the majority of outpatient and hospital care after March 17, 2020, yet they represented only 26% of VTM encounters. We were unable to determine whether this observed difference by race in VTM care was due to patient preference, differences in access to VTM, or some other factor. Future studies should consider this issue carefully in light of well-known disparities in asthma prevalence, severity, and exacerbations by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in the United States,36, 37, 38 as well as concern for a potential “digital divide” in telemedicine.39, 40, 41

Changes in respiratory virus infection rates may have contributed to the decrease in asthma encounters we observed. Most notably, we found that cases of positive RV testing decreased after the introduction of public health interventions designed to limit viral transmission of SARS-CoV-2. This is relevant because RV is a key cause of asthma exacerbations.10 , 11 The other 3 viruses examined (IFV-A, IFV-B, RSV) were waning by March 17, 2020, and as such likely did not play as active a role in asthma exacerbations that occurred after this date. However, we note that we were limited when comparing viral data trends across years because of variability in seasonal onset and peak timing. This variability led to mixed results on the impact of COVID-19 public health interventions on RSV. Overall, a clinically impactful effect of COVID-19–related public health interventions on RSV was unlikely, although the decrease in RV may have contributed to a decrease in asthma exacerbations after March 17.

Air pollution levels are known to vary according to season: PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations across the United States are relatively higher in summer and lower in winter,42 whereas ground-level ozone and NO2 are inversely related, with levels peaking in summer and winter, respectively.43 Our results for each of these 4 criteria air pollutants across the January 17 to May 17 time frame in Philadelphia are consistent with known seasonal trends. Although we did not observe statistically significant changes after COVID-19 public health interventions for these 4 pollutants, the dramatic reduction in vehicular traffic and some industrial activity likely reduced levels of specific pollutants not captured by EPA regulatory monitors. NO2 and PM10 comparisons were limited because they involved 2 different sources of data: AirNow and AirData. Although the same monitoring sites provided data to these publicly available resources, they differed in that AirData releases quality-assured data, whereas AirNow releases real-time measures. Hence, only AirNow contained 2020 measures, whereas only AirData contained complete historical measures. This limitation would likely not change our conclusions because comparison of PM2.5 and ozone measures derived from AirNow and AirData for the period 2015 to 2019 revealed that they were broadly similar. In addition, controlled interrupted time series results were similar whether AirNow or AirData historical measures were used for these 2 pollutants (Table E2). Our pollution results were also limited because they relied on measures taken at specific monitoring sites that may not have adequately captured differences experienced by individuals across the greater Philadelphia region. In addition to potentially changing levels of outdoor air pollutants, COVID-19–related public health interventions likely influenced pollution exposure profiles of children in other ways, including via decreased commuting and outdoor activity.

An additional factor that may have contributed to the reduced asthma disease burden and health care utilization after COVID-19 public health interventions were introduced is increased implementation of preventative measures. For example, some providers may have purposefully reached out to patients' families to encourage filling controller medication prescriptions as the COVID-19 pandemic began, given initial concern that those with asthma had increased susceptibility to more severe outcomes with SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, fear of contracting COVID-19 may have reduced the likelihood of an individual accessing in-person care, as well as increased adherence to controller medications.44 Finally, just as social distancing and increased time spent indoors may have limited patient exposure to viruses and outdoor pollution, these measures may have also decreased exposure to outdoor environmental allergens that are known triggers of pediatric asthma.45 School closures may have additionally resulted in reduced exposure to allergens because school environments can be sources of allergens that increase asthma morbidity.46 , 47

Our study is subject to additional limitations worth noting. The demographic, health care utilization, and viral testing data were derived from a single institution and collected as part of routine care. Therefore, our results may not generalize to other regions and are observational in nature. We relied on primary International Classification of Diseases codes to identify asthma encounters, which may be affected by billing or administrative constraints, and hence may have introduced bias in our data collection. Our prescription data are incomplete in that patients may have sought care outside of our network, and it is limited in that we do not have information on prescriptions filled or adherence. Furthermore, we observed an increase in steroid prescriptions in 2020 as compared with previous years. This increase could be due to shifts in patient acuity, or provider prescription practices. Finally, use of electronic health record–derived data is subject to bias and error more broadly, which we were unable to control for, although most errors in the data would have biased us toward not observing significant changes. As such, future studies are warranted to refine our findings and improve our understanding of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on asthma care, triggers, and clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rebecca A. Hubbard, PhD, for statistical advice. Figure 5 was created with BioRender.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant no. K08DK116668 to D.A.H.; grant nos. R01HL133433 and R01HL141992 to B.E.H.; grant nos. P30ES013508 and K08AI135091 to S.E.H.; grant no. K23HL136842 to C.C.K.; and grant no. R25HL084665 to K.T.), the American College of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (D.A.H.), the American Academy of Allergy Asthma and Immunology (D.A.H.), the American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (D.A.H.), the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (S.E.H.), and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute Developmental Awards (D.A.H. and S.E.H.). The content of this work is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest: S. E. Henrickson has served on prior ad hoc advisory boards for Horizon Pharma, unrelated to this study. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository.

Table E1.

Asthma medication classes

| Medicine ID no. | Name | Class |

|---|---|---|

| 61180 | Decadron IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 61181 | Decadron IV | Systemic steroid |

| 61183 | Decadron OR | Systemic steroid |

| 132559 | DEX Combo 8-4 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132710 | DEX Combo IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 132560 | DEX LA 16 16 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132711 | DEX LA 16 IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 132561 | DEX LA 8 8 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132712 | DEX LA 8 IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 130359 | Dexameth SOD PHOS-BUPIV-LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 90302 | Dexamethasone (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 61547 | Dexamethasone (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200162 | Dexamethasone 0.1 mg/mL (D5W) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 200200163 | Dexamethasone 0.1 mg/mL (NSS) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 2762 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200499 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2759 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL OR ELIX | Systemic steroid |

| 2760 | Dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 2763 | Dexamethasone 0.75 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 2764 | Dexamethasone 1 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200201009 | Dexamethasone 1 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 200200164 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL (D5W) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 200200874 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL (NSS) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 21292 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 200200501 | Dexamethasone 1 mg/mL OR CONC (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 135377 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg (21) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135378 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg (35) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135379 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg (51) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 2765 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200502 | Dexamethasone 1.5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2766 | Dexamethasone 2 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200201008 | Dexamethasone 2 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2767 | Dexamethasone 4 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200503 | Dexamethasone 4 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 200200504 | Dexamethasone 4 mg/mL (undiluted) injection (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 200200165 | Dexamethasone 4 mg/mL (undiluted) injection custom | Systemic steroid |

| 2768 | Dexamethasone 6 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200505 | Dexamethasone 6 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 132777 | Dexamethasone ACE & SOD PHOS | Systemic steroid |

| 132551 | Dexamethasone ACE & SOD PHOS 8-4 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132713 | Dexamethasone ACE & SOD PHOS IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 90303 | Dexamethasone acetate | Systemic steroid |

| 29197 | Dexamethasone acetate 16 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 2769 | Dexamethasone acetate 8 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 61549 | Dexamethasone acetate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 2770 | Dexamethasone acetate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 27267 | Dexamethasone base POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 200200166 | Dexamethasone injection custom orderable | Systemic steroid |

| 200200506 | Dexamethasone injection custom orderable (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 2758 | Dexamethasone Intensol 1 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 61551 | Dexamethasone Intensol OR | Systemic steroid |

| 61554 | Dexamethasone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 18270 | Dexamethasone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 130355 | Dexamethasone SOD PHOS & BUPIV | Systemic steroid |

| 130356 | Dexamethasone SOD PHOS-LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 121371 | Dexamethasone SOD Phosphate PF 10 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 121730 | Dexamethasone SOD Phosphate PF IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 200201236 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (CHEMO) 4 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 90304 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 2771 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 10 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 200201160 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 10 mg/mL IJ SOLN (CHEMO) | Systemic steroid |

| 128185 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 100 mg/10 mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 128184 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 120 mg/30 mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 128183 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 20 mg/5 mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 2772 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 4 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 200201065 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate 4 mg/mL INH SOLN custom | Systemic steroid |

| 61557 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 61558 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate IV | Systemic steroid |

| 2776 | Dexamethasone sodium phosphate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 135753 | DEXPAK 10 DAY 1.5 mg (35) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 97925 | DEXPAK 10 DAY OR | Systemic steroid |

| 135749 | DEXPAK 13 DAY 1.5 mg (51) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 61586 | DEXPAK 13 DAY OR | Systemic steroid |

| 135755 | DEXPAK 6 DAY 1.5 mg (21) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 100127 | DEXPAK 6 DAY OR | Systemic steroid |

| 130145 | Doubledex 10 mg/mL IJ KIT | Systemic steroid |

| 130264 | Doubledex IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 70802 | Medrol (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 17892 | Medrol 16 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 5790 | Medrol 2 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 5792 | Medrol 32 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 17891 | Medrol 4 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 135742 | Medrol 4 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 5793 | Medrol 8 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 70803 | Medrol OR | Systemic steroid |

| 71141 | Methylpred 40 IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 130360 | Methylprednisol & BUPIV & LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 90309 | Methylprednisolone | Systemic steroid |

| 128079 | Methylprednisolone & lidocaine IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 200200507 | Methylprednisolone (CHEMO) injection custom orderable | Systemic steroid |

| 71143 | Methylprednisolone (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 5957 | Methylprednisolone 16 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 12408 | Methylprednisolone 2 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 12410 | Methylprednisolone 32 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 5958 | Methylprednisolone 4 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 135372 | Methylprednisolone 4 mg OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 12411 | Methylprednisolone 8 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 128116 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO | Systemic steroid |

| 132562 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO 40-10 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132542 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO 80-10 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 132732 | Methylprednisolone ACE-LIDO IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 90310 | Methylprednisolone acetate | Systemic steroid |

| 132539 | Methylprednisolone acetate 100 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 5959 | Methylprednisolone acetate 20 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 5959 | Methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 200201903 | Methylprednisolone acetate 40 mg/mL IJ SUSP (IR use only) C | Systemic steroid |

| 5961 | Methylprednisolone acetate 80 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 71145 | Methylprednisolone acetate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 121372 | Methylprednisolone acetate PF 40 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 121373 | Methylprednisolone acetate PF 80 mg/mL IJ SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 121778 | Methylprednisolone acetate PF IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 20399 | Methylprednisolone acetate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 200200293 | Methylprednisolone injection custom orderable | Systemic steroid |

| 71147 | Methylprednisolone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 20398 | Methylprednisolone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 200200508 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (CHEMO) 1 mg/mL (NSS) INJECT | Systemic steroid |

| 200200509 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (CHEMO) 1000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200510 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (CHEMO) 125 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200201004 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (CHEMO) 125 mg/mL (SWFI) INJ | Systemic steroid |

| 200200511 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (CHEMO) 40 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200201002 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (CHEMO) 40 mg/mL (SWFI) INJ | Systemic steroid |

| 90311 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 52078 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 1 g IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200294 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 1 mg/mL (NSS) Injection CUST | Systemic steroid |

| 12412 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 1000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 12413 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 125 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200201001 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 125 mg/mL (SWFI) Injection C | Systemic steroid |

| 12414 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 2000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 12415 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 40 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200999 | Methylprednisolone sodium SUCC 40 mg/mL (SWFI) injection CU | Systemic steroid |

| 12416 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ 500 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 71149 | Methylprednisolone sodium Succ IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 89026 | Millipred 10 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 97492 | Millipred 5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 135762 | Millipred DP 12-DAY 5 mg (48) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 111603 | Millipred DP 12-DAY OR | Systemic steroid |

| 135756 | Millipred DP 5 MG (21) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135757 | Millipred DP 5 mg (48) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 100265 | Millipred DP OR | Systemic steroid |

| 89183 | Millipred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 33929 | Orapred 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 51263 | Orapred ODT 10 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 50493 | Orapred ODT 15 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 51264 | Orapred ODT 30 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 73649 | Orapred ODT OR | Systemic steroid |

| 73650 | ORAPRED OR | Systemic steroid |

| 97196 | Pediapred 6.7 (5 mg prednisolone base) mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 74412 | Pediapred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 90312 | Prednisolone | Systemic steroid |

| 100776 | Prednisolone 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 13018 | Prednisolone 15 mg/5 mL OR SYRP | Systemic steroid |

| 135373 | Prednisolone 5 mg (21) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135374 | Prednisolone 5 mg (48) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 7711 | Prednisolone 5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 90313 | Prednisolone acetate (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 108953 | Prednisolone acetate 16.7 (15 mg base) mg/5 mL OR SUSP | Systemic steroid |

| 75589 | Prednisolone acetate IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 109427 | Prednisolone acetate OR | Systemic steroid |

| 7716 | Prednisolone acetate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 20923 | Prednisolone anhydrous POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 75593 | Prednisolone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 7712 | Prednisolone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 75595 | Prednisolone SOD phosphate OR | Systemic steroid |

| 90314 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate (glucocorticosteroids) | Systemic steroid |

| 51252 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 10 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 89025 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 10 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 50481 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 200201856 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg/5 mL (SWISH & SPIT) OR S | Systemic steroid |

| 33930 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 200200533 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 15 mg/5 mL OR SOLN (CHEMO) Cus | Systemic steroid |

| 97477 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 20 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 121526 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 25 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 51253 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 30 mg OR TBDP | Systemic steroid |

| 96082 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate 6.7 (5 mg base) mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 75598 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate OR | Systemic steroid |

| 20439 | Prednisolone sodium phosphate POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 90315 | Prednisone | Systemic steroid |

| 75601 | Prednisone (PAK) OR | Systemic steroid |

| 200200351 | Prednisone 0.5 mg/mL OR SOL custom | Systemic steroid |

| 7721 | Prednisone 1 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200492 | Prednisone 1 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 120527 | Prednisone 1 mg OR TBEC | Systemic steroid |

| 135431 | Prednisone 10 mg (21) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135432 | Prednisone 10 mg (48) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 7722 | Prednisone 10 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200493 | Prednisone 10 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 120528 | Prednisone 2 mg OR TBEC | Systemic steroid |

| 7723 | Prednisone 2.5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200494 | Prednisone 2.5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 7724 | Prednisone 20 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200495 | Prednisone 20 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 135375 | Prednisone 5 mg (21) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 135376 | Prednisone 5 mg (48) OR TBPK | Systemic steroid |

| 7725 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 200200496 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TABS (CHEMO) custom | Systemic steroid |

| 120529 | Prednisone 5 mg OR TBEC | Systemic steroid |

| 7720 | Prednisone 5 mg/5 mL OR SOLN | Systemic steroid |

| 7718 | Prednisone 5 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 7726 | Prednisone 50 mg OR TABS | Systemic steroid |

| 22674 | Prednisone intensol 5 mg/mL OR CONC | Systemic steroid |

| 75602 | Prednisone Intensol OR | Systemic steroid |

| 75603 | Prednisone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 7727 | Prednisone POWD | Systemic steroid |

| 7732 | Prelone 15 mg/5 mL OR SYRP | Systemic steroid |

| 75620 | Prelone OR | Systemic steroid |

| 8767 | Solu-Medrol 1000 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8768 | Solu-Medrol 125 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8769 | Solu-Medrol 2 g IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8770 | Solu-Medrol 40 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 8771 | Solu-Medrol 500 mg IJ SOLR | Systemic steroid |

| 79793 | Solu-Medrol IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 79797 | Solurex IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 79798 | Solurex LA IJ | Systemic steroid |

| 80064 | Sterapred 12 DAY OR | Systemic steroid |

| 80065 | Sterapred DS 12 DAY OR | Systemic steroid |

| 80066 | Sterapred DS OR | Systemic steroid |

| 80067 | Sterapred OR | Systemic steroid |

| 36549 | Accuneb 0.63 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 36550 | Accuneb 1.25 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 53821 | Accuneb IN | Beta-agonist |

| 54377 | Airet IN | Beta-agonist |

| 91225 | Albuterol | Beta-agonist |

| 54543 | Albuterol IN | Beta-agonist |

| 20261 | Albuterol POWD | Beta-agonist |

| 91226 | Albuterol sulfate | Beta-agonist |

| 311 | Albuterol sulfate (2.5 mg/3 mL) 0.083% IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 312 | Albuterol sulfate (5 mg/mL) 0.5% IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 200200745 | Albuterol sulfate (5 mg/mL) 0.5% NEB continuous custom | Beta-agonist |

| 36541 | Albuterol sulfate 0.63 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 36542 | Albuterol sulfate 1.25 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 132129 | Albuterol sulfate 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AEPB | Beta-agonist |

| 315 | Albuterol sulfate 2 mg OR TABS | Beta-agonist |

| 314 | Albuterol sulfate 2 mg/5 mL OR SYRP | Beta-agonist |

| 316 | Albuterol sulfate 4 mg OR TABS | Beta-agonist |

| 39219 | Albuterol sulfate ER 4 mg OR TB12 | Beta-agonist |

| 39220 | Albuterol sulfate ER 8 mg OR TB12 | Beta-agonist |

| 123418 | Albuterol sulfate ER OR | Beta-agonist |

| 21155 | Albuterol sulfate HFA 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AERS | Beta-agonist |

| 200200995 | Albuterol sulfate HFA 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AERS (ED HOM) | Beta-agonist |

| 200200994 | Albuterol sulfate HFA 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AERS (OR Use) | Beta-agonist |

| 98773 | Albuterol sulfate HFA IN | Beta-agonist |

| 54545 | Albuterol sulfate IN | Beta-agonist |

| 54546 | Albuterol sulfate OR | Beta-agonist |

| 317 | Albuterol sulfate POWD | Beta-agonist |

| 2002001992 | Albuterol sulfate variable dose for Pyxis | Beta-agonist |

| 91234 | Levalbuterol HCL (sympathomimetics) | Beta-agonist |

| 37337 | Levalbuterol HCL 0.31 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 29159 | Levalbuterol HCL 0.63 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 44604 | Levalbuterol HCL 1.25 mg/0.5 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 29160 | Levalbuterol HCL 1.25 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 69516 | Levalbuterol HCL IN | Beta-agonist |

| 91235 | Levalbuterol tartrate | Beta-agonist |

| 49020 | Levalbuterol tartrate 45 μg/ACT IN AERO | Beta-agonist |

| 69517 | Levalbuterol tartrate IN | Beta-agonist |

| 50377 | Proair HFA 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AERS | Beta-agonist |

| 75956 | Proair HFA IN | Beta-agonist |

| 132126 | Proair respiclick 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AEPB | Beta-agonist |

| 132374 | Proair respiclick IN | Beta-agonist |

| 21277 | Proventil HFA 108 (90 μg base) μg/ACT IN AERS | Beta-agonist |

| 76250 | Proventil HFA IN | Beta-agonist |

| 76251 | Proventil IN | Beta-agonist |

| 76252 | Proventil OR | Beta-agonist |

| 200200406 | Terbutaline 0.1% nebulization SOLN custom | Beta-agonist |

| 91239 | Terbutaline sulfate | Beta-agonist |

| 200200937 | Terbutaline sulfate 0.1 mg/mL IJ SOLN custom | Beta-agonist |

| 13430 | Terbutaline sulfate 1 mg/mL IJ SOLN | Beta-agonist |

| 200201165 | Terbutaline sulfate 1 mg/mL IJ SOLN (subcutaneous use only) | Beta-agonist |

| 200200407 | Terbutaline sulfate 1 mg/mL SUSP custom | Beta-agonist |

| 13432 | Terbutaline sulfate 2.5 mg OR TABS | Beta-agonist |

| 13433 | Terbutaline sulfate 5 mg OR TABS | Beta-agonist |

| 81143 | Terbutaline sulfate IJ | Beta-agonist |

| 200200938 | Terbutaline sulfate injection custom orderable | Beta-agonist |

| 81144 | Terbutaline sulfate OR | Beta-agonist |

| 20433 | Terbutaline sulfate POWD | Beta-agonist |

| 37396 | Xopenex 0.31 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 29270 | Xopenex 0.63 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 29271 | Xopenex 1.25 mg/3 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 44598 | Xopenex concentrate 1.25 mg/0.5 mL IN NEBU | Beta-agonist |

| 83997 | Xopenex concentrate IN | Beta-agonist |

| 49017 | Xopenex HFA 45 μg/ACT IN AERO | Beta-agonist |

| 83998 | Xopenex HFA IN | Beta-agonist |

| 83999 | Xopenex IN | Beta-agonist |

| 54262 | Aerobid IN | ICS |

| 54263 | Aerobid-M IN | ICS |

| 127561 | Aerospan 80 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 127718 | Aerospan IN | ICS |

| 96592 | Alvesco 160 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 96591 | Alvesco 80 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 97729 | Alvesco IN | ICS |

| 130919 | Arnuity Ellipta 100 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 130920 | Arnuity Ellipta 200 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 130972 | Arnuity Ellipta IN | ICS |

| 47449 | Asmanex 120 metered doses 220 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 55726 | Asmanex 120 metered doses IN | ICS |

| 47450 | Asmanex 14 metered doses 220 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 55727 | Asmanex 14 metered doses IN | ICS |

| 89591 | Asmanex 30 metered doses 110 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 47447 | Asmanex 30 metered doses 220 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 55728 | Asmanex 30 metered doses IN | ICS |

| 47448 | Asmanex 60 metered doses 220 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 55729 | Asmanex 60 metered doses IN | ICS |

| 111284 | Asmanex 7 metered doses 110 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 111529 | Asmanex 7 metered doses IN | ICS |

| 130881 | Asmanex HFA 100 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 130893 | Asmanex HFA 200 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 130973 | Asmanex HFA IN | ICS |

| 56112 | Azmacort IN | ICS |

| 91254 | Beclomethasone dipropionate (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 33588 | Beclomethasone dipropionate 40 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 33589 | Beclomethasone dipropionate 80 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 56626 | Beclomethasone dipropionate IN | ICS |

| 56627 | Beclovent IN | ICS |

| 91255 | Budesonide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 33341 | Budesonide 0.25 mg/2 mL IN SUSP | ICS |

| 33342 | Budesonide 0.5 mg/2 mL IN SUSP | ICS |

| 200201034 | Budesonide 0.5 mg/2 mL NEB for po use | ICS |

| 85108 | Budesonide 1 mg/2 mL IN SUSP | ICS |

| 98957 | Budesonide 180 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 98956 | Budesonide 90 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 98788 | Budesonide IN | ICS |

| 98448 | Ciclesonide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 96103 | Ciclesonide 160 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 96102 | Ciclesonide 80 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 97832 | Ciclesonide IN | ICS |

| 98924 | Flovent Diskus 100 μg/BLIST IN AEPB | ICS |

| 98925 | Flovent Diskus 250 μg/BLIST IN AEPB | ICS |

| 53294 | Flovent Diskus 50 μg/BLIST IN AEPB | ICS |

| 64815 | Flovent Diskus IN | ICS |

| 46255 | Flovent HFA 110 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 46256 | Flovent HFA 220 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 46254 | Flovent HFA 44 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 64816 | Flovent HFA IN | ICS |

| 64817 | Flovent IN | ICS |

| 64818 | Flovent Rotadisk IN | ICS |

| 91256 | Flunisolide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 127699 | Flunisolide HFA | ICS |

| 127438 | Flunisolide HFA 80 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 127758 | Flunisolide HFA IN | ICS |

| 64856 | Flunisolide IN | ICS |

| 20361 | Flunisolide POWD | ICS |

| 131120 | Fluticasone furoate (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 130716 | Fluticasone furoate 100 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 130717 | Fluticasone furoate 200 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 131018 | Fluticasone furoate IN | ICS |

| 91257 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) | ICS |

| 32750 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) 100 μg/BLIST IN AEPB | ICS |

| 32751 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) 250 μg/BLIST IN AEPB | ICS |

| 32749 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) 50 μg/BLIST IN AEPB | ICS |

| 64934 | Fluticasone propionate (INHAL) IN | ICS |

| 91258 | Fluticasone propionate HFA | ICS |

| 46046 | Fluticasone propionate HFA 110 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 46047 | Fluticasone propionate HFA 220 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 46045 | Fluticasone propionate HFA 44 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 134419 | Fluticasone propionate HFA IN | ICS |

| 91259 | Mometasone furoate (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 130882 | Mometasone furoate 100 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 89590 | Mometasone furoate 110 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 130883 | Mometasone furoate 200 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS |

| 47345 | Mometasone furoate 220 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS |

| 71565 | Mometasone furoate IN | ICS |

| 33535 | Pulmicort 0.25 mg/2 mL IN SUSP | ICS |

| 33536 | Pulmicort 0.5 mg/2 mL IN SUSP | ICS |

| 85111 | Pulmicort 1 mg/2 mL IN SUSP | ICS |

| 99899 | Pulmicort flexhaler 180 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 99900 | Pulmicort flexhaler 90 μg/ACT IN AEPB | ICS |

| 76405 | Pulmicort flexhaler IN | ICS |

| 76406 | Pulmicort IN | ICS |

| 76407 | Pulmicort turbuhaler IN | ICS |

| 33585 | QVAR 40 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 33586 | QVAR 80 μg/ACT IN AERS | ICS |

| 76802 | QVAR IN | ICS |

| 91260 | Triamcinolone acetonide (steroid inhalants) | ICS |

| 85453 | Triamcinolone acetonide IN | ICS |

| 83089 | Vanceril double strength IN | ICS |

| 83090 | Vanceril IN | ICS |

| 105585 | Advair Diskus 100-50 μg/dose IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 105588 | Advair Diskus 250-50 μg/dose IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 105589 | Advair Diskus 500-50 μg/dose IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 54204 | Advair Diskus IN | ICS + LABA |

| 50623 | Advair HFA 115-21 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 50624 | Advair HFA 230-21 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 50622 | Advair HFA 45-21 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 54205 | Advair HFA IN | ICS + LABA |

| 125719 | BREO Ellipta 100-25 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 132901 | BREO Ellipta 200-25 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 125944 | BREO Ellipta IN | ICS + LABA |

| 91246 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate | ICS + LABA |

| 53024 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate 160-4.5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 53023 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate 80-4.5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 57629 | Budesonide-formoterol fumarate IN | ICS + LABA |

| 110610 | Dulera 100-5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110611 | Dulera 200-5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110811 | Dulera IN | ICS + LABA |

| 126085 | Fluticasone furoate-Vilanterol | ICS + LABA |

| 125641 | Fluticasone furoate-Vilanterol 100-25 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 132806 | Fluticasone furoate-Vilanterol 200-25 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 125999 | Fluticasone furoate-Vilanterol IN | ICS + LABA |

| 91247 | Fluticasone-salmeterol | ICS + LABA |

| 105249 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 100-50 μg/dose IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 50619 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 115-21 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 50620 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 230-21 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 105250 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 250-50 μg/dose IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 50618 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 45-21 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 105251 | Fluticasone-salmeterol 500-50 μg/dose IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 64938 | Fluticasone-salmeterol IN | ICS + LABA |

| 111224 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM | ICS + LABA |

| 110576 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM 100-5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110577 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM 200-5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 110835 | Mometasone furo-formoterol FUM IN | ICS + LABA |

| 53239 | Symbicort 160-4.5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 53238 | Symbicort 80-4.5 μg/ACT IN AERO | ICS + LABA |

| 80691 | Symbicort IN | ICS + LABA |

| 128121 | Umeclidinium-Vilanterol | ICS + LABA |

| 127865 | UMeclidinium-Vilanterol 62.5-25 μg/INH IN AEPB | ICS + LABA |

| 128105 | Umeclidinium-Vilanterol IN | ICS + LABA |

| 30756 | Accolate 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 21303 | Accolate 20 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 53764 | Accolate OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 91262 | Montelukast sodium (leukotriene modulators) | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26447 | Montelukast sodium 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 31645 | Montelukast sodium 4 mg OR CHEW | Leukotriene modulators |

| 41211 | Montelukast sodium 4 mg OR PKT | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26448 | Montelukast sodium 5 mg OR Chew | Leukotriene modulators |

| 71666 | Montelukast sodium OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26454 | Singulair 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 31649 | Singulair 4 mg OR Chew | Leukotriene modulators |

| 41210 | Singulair 4 mg OR PKT | Leukotriene modulators |

| 26451 | Singulair 5 mg OR Chew | Leukotriene modulators |

| 79047 | Singulair OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 91263 | Zafirlukast | Leukotriene modulators |

| 30767 | Zafirlukast 10 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 21309 | Zafirlukast 20 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 84136 | Zafirlukast OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 91261 | Zileuton | Leukotriene modulators |

| 22305 | Zileuton 600 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 85485 | Zileuton ER 600 mg OR TB12 | Leukotriene modulators |

| 120894 | Zileuton ER OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 84194 | Zileuton OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 22304 | Zyflo 600 mg OR TABS | Leukotriene modulators |

| 85530 | Zyflo CR 600 mg OR TB12 | Leukotriene modulators |

| 85882 | Zyflo CR OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 84345 | Zyflo OR | Leukotriene modulators |

| 134493 | Mepolizumab | Biologics |

| 134274 | Mepolizumab 100 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 134437 | Mepolizumab SC | Biologics |

| 134298 | Nucala 100 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 134446 | Nucala SC | Biologics |

| 91264 | Omalizumab | Biologics |

| 41330 | Omalizumab 150 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 73347 | Omalizumab SC | Biologics |

| 41342 | Xolair 150 mg SC SOLR | Biologics |

| 83995 | Xolair SC | Biologics |

| 120900 | Aclidinium bromide | Anticholinergics |

| 120515 | Aclidinium bromide 400 μg/ACT IN AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 120732 | Aclidinium bromide IN | Anticholinergics |

| 46720 | Atrovent HFA 17 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 55931 | Atrovent HFA IN | Anticholinergics |

| 55932 | Atrovent IN | Anticholinergics |

| 134491 | Glycopyrrolate (bronchodilators-anticholinergics) | Anticholinergics |

| 134424 | Glycopyrrolate IN | Anticholinergics |

| 130918 | Incruse Ellipta 62.5 μg/INH IN AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 131033 | Incruse Ellipta IN | Anticholinergics |

| 91220 | Ipratropium bromide (bronchodilators- anticholinergics) | Anticholinergics |

| 14727 | Ipratropium bromide 0.02 % IN SOLN | Anticholinergics |

| 91221 | Ipratropium bromide HFA | Anticholinergics |

| 46527 | Ipratropium bromide HFA 17 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 68438 | Ipratropium bromide HFA IN | Anticholinergics |

| 68439 | Ipratropium bromide IN | Anticholinergics |

| 20367 | Ipratropium bromide POWD | Anticholinergics |

| 134455 | Seebri Neohaler IN | Anticholinergics |

| 43683 | Spiriva Handihaler 18 μg IN CAPS | Anticholinergics |

| 79945 | Spiriva Handihaler IN | Anticholinergics |

| 133764 | Spiriva Respimat 1.25 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 130566 | Spiriva Respimat 2.5 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 130663 | Spiriva Respimat IN | Anticholinergics |

| 91222 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate | Anticholinergics |

| 133714 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate 1.25 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 43672 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate 18 μg IN CAPS | Anticholinergics |

| 130394 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate 2.5 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 81562 | Tiotropium bromide monohydrate IN | Anticholinergics |

| 120704 | Tudorza Pressair 400 μg/ACT IN AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 120880 | Tudorza Pressair IN | Anticholinergics |

| 131119 | Umeclidinium bromide | Anticholinergics |

| 130705 | Umeclidinium bromide 62.5 μg/INH IN AEPB | Anticholinergics |

| 131098 | Umeclidinium bromide IN | Anticholinergics |

| 91245 | Ipratropium-albuterol | Anticholinergics |

| 97202 | Ipratropium-albuterol 0.5-2.5 (3) mg/3 mL IN SOLN | Anticholinergics |

| 16477 | Ipratropium-albuterol 18-103 μg/ACT IN AERO | Anticholinergics |

| 119838 | Ipratropium-albuterol 20-100 μg/ACT IN AERS | Anticholinergics |

| 98087 | Ipratropium-albuterol IN | Anticholinergics |

AERO, Aerosolized; AERS, aerosolized; CHEMO, chemotherapy; CONC, concentrate; CUST, custom; D5W, dextrose 5% in water; Dex, dexamethasone; ELIX, elixer; ER, extended-release; HCL, hydrochloride; HFA, hydrofluoroalkane; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; IJ, injection; IN, inhallation; INH, inhallation; INHAL, inhallation; INJ, injection; INJECT, injection; IV, intravenous; LABA, long-acting beta agonist; LIDO, lidocaine; NEB, nebulizer; NEBU, nebulizer; NSS, normal saline solution; OR, oral; PAK, pack; PHOS, phosphate; PKT, packet; po, per os (by mouth); POWD, powder; SC, subcutaneous; SOD, sodium; SOL, solution; SOLN, solution; SUSP, suspension; SWFI, sterile water for injection; SYRP, syrup; TABS, tablets; TBEC, enteric coated tablet; TBPK, tablet pack.

Table E2.

Demographic characteristics of asthma prescription encounters

| Characteristic | Prescription cohort (n) |

|

|---|---|---|

| All medicines (1624) | Steroids (402) | |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 917 (56) | 213 (53) |

| Female | 708 (44) | 189 (47) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 664 (41) | 74 (18) |

| Black | 666 (41) | 280 (70) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 36 (2) | 6 (1) |

| Other | 252 (16) | 42 (10) |

| Unknown | 7 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1434 (88) | 372 (93) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 180 (11) | 30 (7) |

| Unknown | 11 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Birth year, n (%) | ||

| Before 2000 | 11 (1) | 1 (0) |

| 2000-2004 | 208 (13) | 62 (15) |

| 2005-2009 | 392 (24) | 85 (21) |

| 2010-2014 | 533 (33) | 131 (33) |

| 2015 or later | 481 (30) | 123 (31) |

| Payer type, n (%) | ||

| Non-Medicaid | 912 (56) | 148 (37) |

| Medicaid | 713 (44) | 254 (63) |

Table E3.

Controlled interrupted time series regression analysis results for 4 criteria air pollutants

| Variables | PM2.5 |

Ozone |

PM10 |

NO2 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AirNow | AirData | AirNow | AirData | AirData | AirData | |

| Days (P value) | −0.03 (.064) | −0.05 (.002) | 0.26 (<.0001) | 0.27 (<.0001) | −0.044 (.23) | −0.07 (.04) |

| Year 2020 (P value) | −3.51 (.0005) | −3.58 (.0002) | 2.18 (.25) | 1.16 (.54) | −5.40 (.004) | −0.77 (.66) |

| Covid_restrictions (P value) | −5.25 (.009) | −4.56 (.019) | 16.08 (<.0001) | 12.90 (.0007) | −0.52 (.88) | −0.33 (.92) |

| Days × Year 2020 (P value) | 0.0009 (.97) | 0.02 (.41) | −0.03 (.52) | −0.04 (.42) | −0.005 (.92) | −0.01 (.70) |

| Days × Covid_restrictions (P value) | 0.045 (.10) | 0.05 (.04) | −0.24 (<.0001) | −0.2 (<.0001) | 0.006 (.90) | −0.001 (.98) |

| Year 2020 × Covid_restrictions (P value) | 2.24 (.42) | 1.56 (.56) | −6.56 (.21) | −3.48 (.51) | −7.57 (.15) | −5.5 (.26) |

| Days × Year 2020 × Covid_restrictions (P value) | −0.005 (.88) | −0.01 (.66) | 0.09 (.2) | 0.05 (.44) | 0.08 (.27) | 0.05 (.41) |

Outcome was levels of each pollutant. Independent variables included days, referring to the 120 d between January 17 and May 17; year 2020, indicating whether it was the year 2020 or historical time period; covid_restrictions, indicating whether the measure was from before or after March 17. Each column corresponds to 1 model with indicated outcome variable and source of historical measures (AirNow or AirData). Terms in the model are indicated in each row. Values are coefficient estimate (P value).

References

- 1.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., Qu J., Gong F., Han Y. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Public Health Emergency Order Temporarily Prohibiting Operation of Non-Essential Businesses and Congregation of Persons to Prevent the Spread of 2019 Novel Coronavirus (Covid-19) https://www.phila.gov/media/20200322134942/HEALTH-ORDER-2-NON-ESSENTIAL-BUSINESSES-AND-INDIVIDUAL-ACTIVITY-STAY-AT-HOME.pdf Available from: Accessed May 1, 2020.

- 4.Santoli J.M., Lindley M.C., DeSilva M.B., Kharbanda E.O., Daley M.F., Galloway L. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on routine pediatric vaccine ordering and administration—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:591–593. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bramer C.A., Kimmins L.M., Swanson R., Kuo J., Vranesich P., Jacques-Carroll L.A. Decline in child vaccination coverage during the COVID-19 pandemic—Michigan Care Improvement Registry, May 2016–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:630–631. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6920e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wosik J., Fudim M., Cameron B., Gellad Z.F., Cho A., Phinney D. Telehealth transformation: COVID-19 and the rise of virtual care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2020;27:957–962. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocaa067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zahran H.S., Bailey C.M., Damon S.A., Garbe P.L., Breysse P.N. Vital signs: asthma in children—United States, 2001-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:149–155. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6705e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hill D.A., Grundmeier R.W., Ram G., Spergel J.M. The epidemiologic characteristics of healthcare provider-diagnosed eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food allergy in children: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16:133. doi: 10.1186/s12887-016-0673-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenyon C.C., Maltenfort M.G., Hubbard R.A., Schinasi L.H., De Roos A.J., Henrickson S.E. Variability in diagnosed asthma in young children in a large pediatric primary care network. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20:958–966. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konrádová V., Hlousková Z., Tománek A. Classification of pathological ultrastructural changes in the bronchial epithelium of children and adults with relapsing chronic respiratory disease. Cesk Pediatr. 1976;31:146–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinogradova M.S. Seasonal dynamics of the gastric APUD cell count in a hibernator. Biull Eksp Biol Med. 1985;100:736–738. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bush A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of asthma. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:68. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mirabelli M.C., Vaidyanathan A., Flanders W.D., Qin X., Garbe P. Outdoor PM2.5, ambient air temperature, and asthma symptoms in the past 14 days among adults with active asthma. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1882–1890. doi: 10.1289/EHP92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orellano P., Quaranta N., Reynoso J., Balbi B., Vasquez J. Effect of outdoor air pollution on asthma exacerbations in children and adults: systematic review and multilevel meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strickland M.J., Darrow L.A., Klein M., Flanders W.D., Sarnat J.A., Waller L.A. Short-term associations between ambient air pollutants and pediatric asthma emergency department visits. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:307–316. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200908-1201OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keet C.A., Keller J.P., Peng R.D. Long-term coarse particulate matter exposure is associated with asthma among children in Medicaid. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:737–746. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1267OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Achakulwisut P., Brauer M., Hystad P., Anenberg S.C. Global, national, and urban burdens of paediatric asthma incidence attributable to ambient NO2 pollution: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet Health. 2019;3:e166–e178. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(19)30046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jartti T., Gern J.E. Role of viral infections in the development and exacerbation of asthma in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corne J.M., Marshall C., Smith S., Schreiber J., Sanderson G., Holgate S.T. Frequency, severity, and duration of rhinovirus infections in asthmatic and non-asthmatic individuals: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2002;359:831–834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07953-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnston S.L. Asthma and COVID-19: is asthma a risk factor for severe outcomes? Allergy. 2020;75:1543–1545. doi: 10.1111/all.14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hegde S. Does asthma make COVID-19 worse? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:352. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J.-J., Dong X., Cao Y.-Y., Yuan Y.-D., Yang Y.-B., Yan Y.-Q. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 2020;75:1730–1741. doi: 10.1111/all.14238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li X., Xu S., Yu M., Wang K., Tao Y., Zhou Y. Risk factors for severity and mortality in adult COVID-19 inpatients in Wuhan. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:110–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahdavinia M., Foster K.J., Jauregui E., Moore D., Adnan D., Andy-Nweye A.B. Asthma prolongs intubation in COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2388–2391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bauwens M., Compernolle S., Stavrakou T., Müller J.F., van Gent J., Eskes H. Impact of coronavirus outbreak on NO2 pollution assessed using TROPOMI and OMI observations. Geophys Res Lett. 2020;47 doi: 10.1029/2020GL087978. e2020GL087978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi X., Brasseur G.P. The response in air quality to the reduction of Chinese economic activities during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geophys Res Lett. 2020;47 doi: 10.1029/2020GL088070. e2020GL088070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallo O., Bruno C., Locatello L.G. Global lockdown, pollution, and respiratory allergic diseases: are we in or are we out? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146:542–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feemster K.A., Li Y., Grundmeier R., Localio A.R., Metlay J.P. Validation of a pediatric primary care network in a US metropolitan region as a community-based infectious disease surveillance system. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2011;2011:219859. doi: 10.1155/2011/219859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.AirNow Data Management Center, Air Quality Data Management Analysis. https://airnowtech.org/ Available from: Accessed May 1, 2020.

- 30.EPA, Pre-generated data files. https://aqs.epa.gov/aqsweb/airdata/download_files.html Available from: Accessed May 1, 2020.

- 31.RC Team, R: a language and environment for statistical computing. 2017. https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=R:+A+language+and+environment+for+statistical+computing&publication_year=2017& Available from: Accessed May 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kenyon C.C., Hill D.A., Henrickson S.E., Bryant-Stephens T.C., Zorc J.J. Initial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric asthma emergency department utilization. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:2774–2776.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]