Abstract

Our study aimed to systematically analyse the risk factors of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with severe disease. An electronic search in eight databases to identify studies describing severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients from 1 January 2020 to 3 April 2020. In the end, we meta-analysed 40 studies involving 5872 COVID-19 patients. The average age was higher in severe COVID-19 patients (weighted mean difference; WMD = 10.69, 95%CI 7.83–13.54). Patients with severe disease showed significantly lower platelet count (WMD = −18.63, 95%CI −30.86 to −6.40) and lymphocyte count (WMD = −0.35, 95%CI −0.41 to −0.30) but higher C-reactive protein (CRP; WMD = 42.7, 95%CI 31.12–54.28), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; WMD = 137.4, 95%CI 105.5–169.3), white blood cell count(WBC), procalcitonin(PCT), D-dimer, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and creatinine(Cr). Similarly, patients who died showed significantly higher WBC, D-dimer, ALT, AST and Cr but similar platelet count and LDH as patients who survived. These results indicate that older age, low platelet count, lymphopenia, elevated levels of LDH, ALT, AST, PCT, Cr and D-dimer are associated with severity of COVID-19 and thus could be used as early identification or even prediction of disease progression.

Key words: Coronavirus disease 2019, critically ill, meta-analysis, risk factors, severe disease

Introduction

In December 2019, Wuhan, China had reported a cluster of unexplained cases of viral pneumonia. This disease was soon named as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and determined to be caused by a novel coronavirus, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [1]. In the past two months, COVID-19 has spread across the globe. According to data released by the World Health Organization (WHO), as of 10:00 on 4 April, SARS-CoV-2 had infected 207 countries, areas or territories with a total of 1 051 697 confirmed cases and 56 986 deaths worldwide [2]. The confirmed cases in America, Italy and Spain have surpassed 100 000 and the cases continue to increase rapidly in across the world [3]. It has become a serious threat to global health and a significant challenge to health care systems worldwide.

While the disease is mild or even asymptomatic in most patients, and usually self-resolves without the need for hospitalisation, there was still a certain proportion of severe cases. The treatment of severe cases was difficult and the fatality rate was high. As of 16 February, China's COVID-19 epidemic report data showed that 19.6% of patients were severe cases [4], and the fatality rate of these cases was 49% [5]. Furthermore, a study included 52 severe case patients showed that the fatality rate was as high as 61.5% [6]. Therefore, it is critical to understand and identify the risk factors for the progression of COVID-19 patients in order to help in early identification of severe cases and improving the prognosis of patients.

Two recent systematic study reviews [7,8] of COVID-19 patients indicated increased procalcitonin values that were associated with a nearly five-fold higher risk of severe infection and low platelet count was associated with increased risk of severe disease and mortality in patients with COVID-19. However, both reviews meta-analysed small samples pooled from few studies and the indicators were not comprehensive. Recently, many large-scale clinical studies have been published [9–12], but the results across these studies were not entirely consistent. In order to gain a clearer picture of the risk factors of severe COVID-19, we meta-analysed the relevant literature. The results may provide a basis for detecting or even predicting disease progression quickly enough to improve prognosis.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

This meta-analysis was carried out according to preferred reporting items for Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) statement [13]. PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, EMbase, CNKI, WanFang Data, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database and VIP databases were electronically searched to collect clinical studies of severe or critically ill COVID-19 patients from 1 January 2020 to 3 April 2020. We also manually searched the lists of included studies to identify additional potentially eligible studies. If there were two or more studies that described the same population, only the study with the largest sample size was chosen. There was no language restriction placed in the literature search, but only literature published online were included. The following keywords were used, both separately and in combination, as part of the search strategy in each database: ‘Coronavirus’, ‘2019-nCoV’, ‘COVID-19’, ‘SARS-CoV-2’, ‘severe’, ‘critical’, ‘icu care’, ‘mechanical ventilation’, ‘intensive care unit’, ‘mortality’, ‘fatal’, ‘death’, ‘survivors’ or ‘critically ill’.

Study Eligibility

Studies were included in the meta-analysis if they had cohort, case−control or case-series designs; if they contained patients with mild and severe disease, or survivor and death groups; the laboratory outcomes of the COVID-19 patients included in our study were the findings when they were admitted to the hospital or first visited the hospital. At the end of the follow-up, the patients were divided into mild and severe groups. We considered disease to be ‘mild’ in those patients described in the studies as having mild or moderate disease, or ‘severe’ in those patients described as having severe disease, as being admitted to the intensive care unit or as requiring mechanical ventilation. Only studies of more than 30 patients were included.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Three reviewers independently selected literature and extracted data to an Excel database. Any disagreement was resolved by another reviewer. The titles and abstracts were first screened to identify the eligible articles, followed by a full-text review to obtain detailed information. When required, the authors were contacted directly to obtain further information and clarifications regarding their study. Data extraction included: The first author's surname and the date of publication of the article, study design, sample size, age, outcome measurement data such as laboratory findings reported in the identified papers, relevant elements of bias risk assessment.

The quality of included studies was independently evaluated by the three reviewers based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [14] guidelines. Any disagreement was resolved by another reviewer. Studies with a score greater than 6 were considered to be of high quality (total score = 9).

Statistical analyses

Data from studies reporting continuous data as ranges or as median and interquartile ranges were converted to mean ± s.d. [15]. The weighted mean differences (WMDs) in continuous variables between patient groups were calculated, together with the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All meta-analyses were performed using STATA 12 (StataCorp, TX, USA). Since all studies were gathered from the published literature and the sample size of included studies varies greatly, so a random-effects model was used. Funnel plot together with Egger's regression asymmetry test and Begg's test were used to evaluate publication bias. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Literature screening and assessment

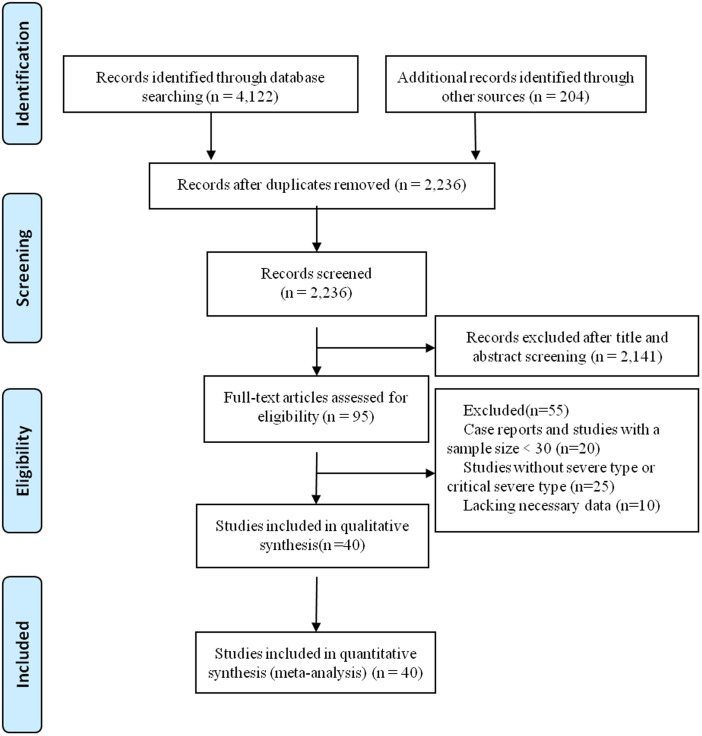

A total of 4122 records were identified from the databases. In addition, 204 records were identified from the Chinese Medical Journal Network. After a detailed assessment, 40 studies [6, 9–12, 16–50] involving 5872 COVID-19 patients were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting literature screening process.

Characteristics of included studies

All studies included in the meta-analysis were conducted in China examined Chinese patients distributed across 31 provinces and published between 8 February 2020 and 2 April 2020. A large proportion of these studies (n = 37) were based on data collected from a single centre. Follow-up data were reported for most patients. All studies received quality scores of 6–9, indicating high quality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies of COVID-19 patients in China

| First author | Publication date in 2020 | n (mild/severe or survival/non-survival) | Male (%) | Single- or multi-centrea | Study population | Ageb, years | Follow-up | Quality scorec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deng [9] | 20 Mar | 109/116 | 32 | Multi | Survival and non-survival COVID-19 patients | 43 ± 18/68±9 | 1 Jan to 21 Feb | 8 |

| Zhou [16] | 11 Mar | 137/54 | 62 | Multi | Survival and non-survival COVID-19 patients | 56(46–67) | As of 31 Jan | 8 |

| Yang [6] | 24 Feb | 20/32 | 67 | Single | Survival and non-survival COVID-19 patients | 59.7–13.3 | 2 Dec 2019 to 23 Jan 2020 | 7 |

| Chen [10] | 26 Mar | 161/113 | 62 | Single | Survival and non-survival COVID-19 patients | 62 (44–70) | As of 28 Feb | 7 |

| Chen [17] | 12 Mar | 282/181 | 53 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 15–90 | As of 6 Feb | 7 |

| Xiao [18] | 27 Feb | 107/36 | 51 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 45.1 ± 1.0 | 23 Jan to 8 Feb | 9 |

| Wang [19] | 8 Feb | 102/36 | 54 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 56(42–68) | 1 Jan to 28 Jan | 7 |

| Yuan [20] | 6 Mar | 192/31 | 47 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 46.5 ± 16 | 24 Jan to 23 Feb | 9 |

| Fang [21] | 25 Feb | 55/24 | 57 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 45 ± 16.6 | 22 Jan to 18 Feb | 6 |

| Liu [22] | 17 Feb | 26/4 | 33 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 35 ± 8 | 10 Jan to 31 Jan | 6 |

| Zhong [23] | 26 Mar | 51/11 | 65 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 51.8 ± 13.5 | 21 Jan to 10 Feb | 6 |

| Guan [24] | 6 Feb | 926/173 | 58 | Multi | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 47.0 | NR | 9 |

| Qian [25] | 17 Mar | 82/9 | 42 | Multi | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 50(36.5–57) | 20 Jan to 11 Feb | 9 |

| Huang [26] | 15 Feb | 28/13 | 73 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 49(41–58) | As of 2 Jan | 7 |

| LI [27] | 29 Feb | 58/25 | 53 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 45.5 ± 12.3 | Jan to Feb | 7 |

| Wan [28] | 21 Mar | 95/40 | 53 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 47(36–55) | 23 Jan to 8 Feb | 8 |

| Gao [29] | 17 Mar | 28/15 | 60 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 45 ± 7.7/43±14 | 23 Jan to 2 Feb | 6 |

| Zhang [30] | 23 Feb | 82/58 | 51 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 57.0 | 16 Jan to 3 Feb | 7 |

| Chen [31] | 13 Mar | 108/31 | 55 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 15–79/36–59 | Jan to Feb | 8 |

| Chen [32] | 17 Mar | 68/21 | 47 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 41.6 ± 15.6 | As of 21 Feb | 7 |

| Li [33] | 26 Mar | 63/17 | 50 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 47.8 ± 19.5 | 20 Jan to 27 Feb | 7 |

| Li [34] | 2 Apr | 40/6 | 46 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | NR | 21 Jan to 16 Feb | 6 |

| Li [35] | 2 Apr | 18/44 | 52 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 49 ± 37/59±31 | 31 Jan to 25 Feb | 6 |

| Liu [11] | 2 Apr | 196/146 | 54 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | NR | 23 Jan to 12 Feb | 7 |

| Zhang [36] | 2 Apr | 56/18 | 47 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 52.7 ± 19 | 21 Jan to 11 Feb | 7 |

| Xiong [37] | 3 Mar | 58/31 | 46 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 53 ± 16.9 | 17 Jan to 20 Feb | 7 |

| Liu [38] | 27 Mar | 84/7 | 62 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | NR | 25 Jan to 18 Feb | 6 |

| Gao [39] | 31 Mar | 57/33 | 48 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 51.7 ± 18.6 | Jan to Feb | 7 |

| Xie [40] | 2 Apr | 51/28 | 56 | Single | COVID-19 patients in Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital | 60(48–66) | 2 Feb to 23 Feb | 7 |

| Zhang [12] | 2 Apr | 84/31 | 40 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 43.9 ± 15/65±1 | As of 22 Feb | 7 |

| Liu [41] | 28 Feb | 67/11 | 49 | Multi | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 38(33,57) | 30 Dec to 15 Jan | 7 |

| Shi [42] | 27 Feb | 150/14 | 45 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | NR | Jan to Feb | 8 |

| Shi [43] | 12 Mar | 38/16 | 57 | Single | Mild, severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients | 62.5 (50.5, 68.5) | 9 Feb to 29 Feb | 6 |

| Peng [44] | 2 Mar | 96/16 | 47 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 62(55,67) | 20 Jan to 15 Feb | 7 |

| Li [45] | 20 Mar | 53/13 | 44 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 18–82 | 20 Jan to 10 Feb | 7 |

| Chen [46] | 27 Feb | 23/25 | 50 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 43.8–69 | 24 Jan to 8 Feb | 6 |

| Wang [47] | 24 Feb | 132/21 | 50 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 43.4 ± 15/57.7±13 | 26 Jan to 5 Feb | 8 |

| Li [48] | 5 Mar | 20/10 | 60 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 21–72 | 22 Jan to 8 Feb | 6 |

| Ling [49] | 18 Mar | 271/21 | 46 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 48.7 ± 16/65.5±16 | 20 Jan to 10 Feb | 9 |

| Bin [50] | 29 Feb | 45/9 | 56 | Single | Mild and severe COVID-19 patients | 53.9 ± 17. 1 | 29 Jan to 16 Feb | 6 |

All studies were retrospective cohort studies.

Reported as range, mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range). NR, not reported.

Score based on the Newcastle−Ottawa scale guidelines [14].

Meta-analysis

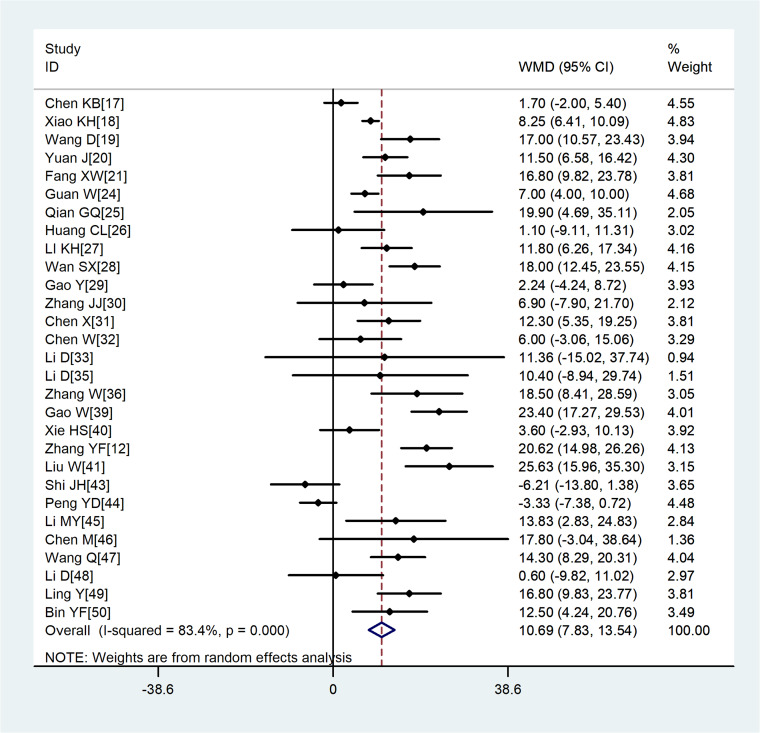

Age distribution

A total of 29 studies involving 3411 COVID-19 patients were included. Although the heterogeneity was high across enrolled studies, the result showed that compared with non-severe group, the age of severe group was higher (WMD = 10.69, 95%CI 7.83–13.54) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Meta-analysis of the difference in the average age between COVID-19 patients with mild or severe disease. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Laboratory parameters

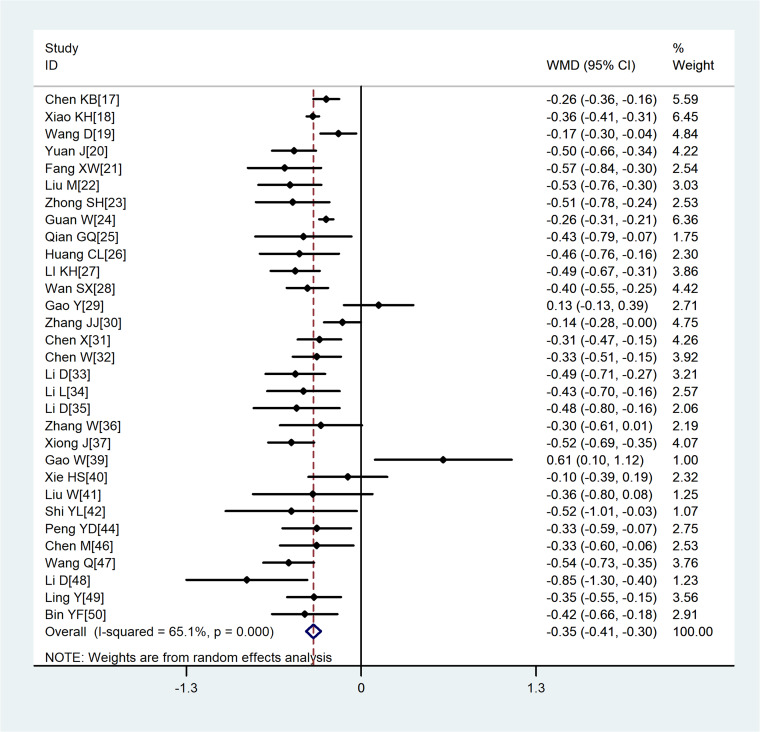

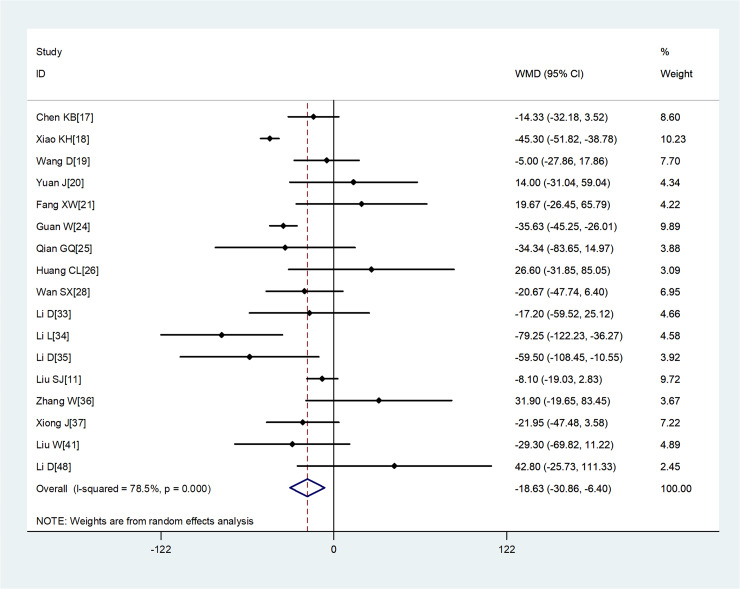

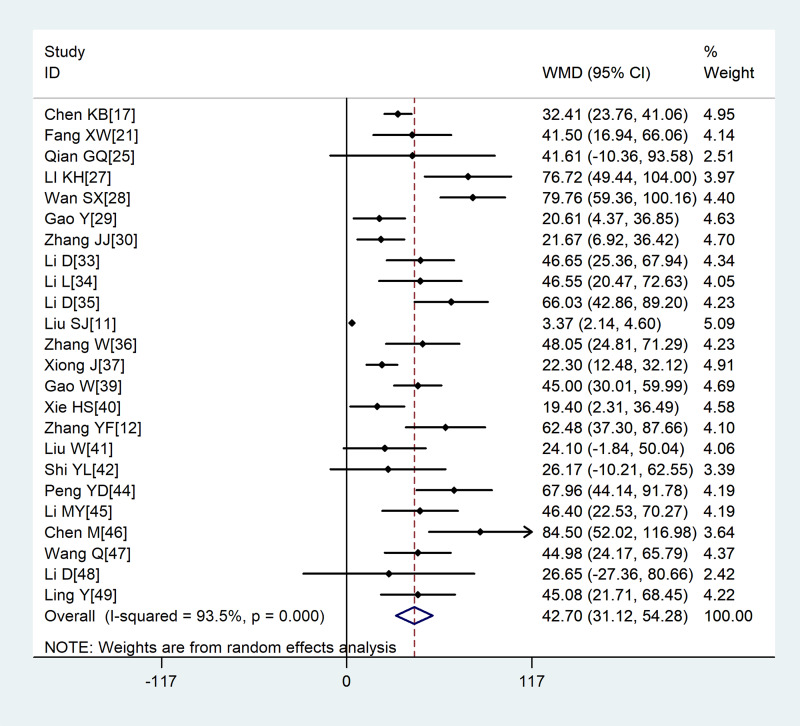

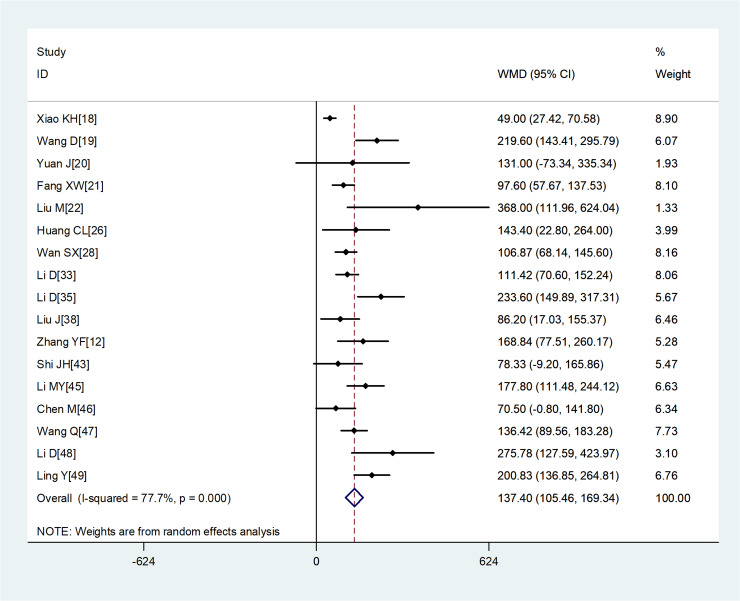

Compared with non-severe group, the lymphocyte count (WMD = −0.35, 95%CI −0.41 to −0.30) and the platelet count (WMD = −18.63, 95%CI −30.86 to −6.40) were found to be lower, while C-reactive protein (CRP; WMD = 42.7, 95%CI 31.12–54.28) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; WMD = 137.4, 95%CI 105.5–169.3) were significantly higher in the severe group (Figs 3–6). Patients in the severe group also displayed elevated levels of white blood cell count (WBC; WMD = 0.93, 95%CI 0.51–1.36), procalcitonin (PCT; WMD = 0.07, 95%CI 0.05–0.10), D-dimer (WMD = 0.38, 95%CI 0.24–0.52), alanine aminotransferase (ALT; WMD = 5.12, 95%CI 0.82–9.42), aspartate aminotransferase (AST; WMD = 8.51, 95%CI 5.01–12.01) and creatinine (Cr; WMD = 4.57, 95%CI 0.64–8.50) compared to those in the non-severe group (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Meta-analysis of the difference in the lymphocyte count between COVID-19 patients with mild or severe disease. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Fig. 4.

Meta-analysis of the difference in the platelet count between COVID-19 patients with mild or severe disease. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of the difference in the C-reactive protein between COVID-19 patients with mild or severe disease. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Fig. 6.

Meta-analysis of the difference in the lactate dehydrogenase between COVID-19 patients with mild or severe disease. WMD, weighted mean difference.

Table 2.

Meta analysis of different laboratory parameters in COVID-19 patients

| Laboratory parameters | No. studies | No. patients | Heterogeneity | Model | Meta analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I2 | WMD(95%CI) | P | ||||

| Severe vs. mild disease | |||||||

| Age, years | 29 | 4306 | < 0.001 | 83.4% | Random | 10.69 (7.83,13.54) | < 0.001 |

| WBC, × 109/l | 32 | 4736 | < 0.001 | 83.2% | Random | 0.93(0.51,1.36) | < 0.001 |

| LBC, × 109/l | 31 | 4456 | < 0.001 | 65.1% | Random | −0.35(−0.41,−0.30) | < 0.001 |

| PLT, × 109/l | 17 | 3211 | < 0.001 | 78.5% | Random | −18.63(−30.86,−6.40) | 0.003 |

| PCT, ng/ml | 23 | 3087 | < 0.001 | 89.8% | Random | 0.07(0.05,0.10) | < 0.001 |

| D-dimer, μg/ml | 18 | 2169 | < 0.001 | 66.3% | Random | 0.38(0.24,0.52) | < 0.001 |

| CRP, mg/l | 24 | 2964 | < 0.001 | 93.5% | Random | 42.7(31.12,54.28) | < 0.001 |

| LDH, U/l | 17 | 1792 | < 0.001 | 77.7% | Random | 137.4(105.46,169.34) | < 0.001 |

| ALT, U/l | 22 | 2440 | < 0.001 | 71.0% | Random | 5.12(0.82,9.42) | 0.020 |

| AST, U/l | 22 | 2452 | < 0.001 | 74.7% | Random | 8.51(5.01,12.01) | < 0.001 |

| Cr, μmol/ml | 17 | 1922 | 0.026 | 61.6% | Random | 4.57(0.64,8.50) | 0.023 |

| Death vs. survival | |||||||

| Age, years | 4 | 742 | 0.002 | 79.2% | Random | 18.68 (14.15,23.21) | < 0.001 |

| WBC, × 109/l | 3 | 690 | 0.024 | 73.3% | Random | 4.14(2.87,5.41) | < 0.001 |

| LBC, × 109/l | 4 | 742 | 0.188 | 37.4% | Random | −0.43(−0.5, −0.35) | < 0.001 |

| PLT, × 109/l | 2 | 243 | 0.001 | 90.9% | Random | −12.94 (−92.78,66.89) | 0.751 |

| D-dimer, μg/ml | 2 | 465 | 0.881 | 0.0% | Random | 8.34 (6.14,10.64) | < 0.001 |

| LDH, U/l | 2 | 465 | < 0.001 | 97.6% | Random | 139.3(−188.05,466.7) | 0.404 |

| ALT, U/l | 3 | 690 | 0.033 | 70.6% | Random | 7.23(2.25,12.2) | 0.004 |

| AST, U/l | 2 | 499 | 0.003 | 88.6% | Random | 16.68 (7.48,25.89) | < 0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Four studies [6, 9, 10, 16] whose primary outcome was death were also analysed. The results showed that on admission, patients who died showed significantly higher WBC, D-dimer, ALT, AST and Cr but similar platelet count and LDH as patients who survived (Table 2).

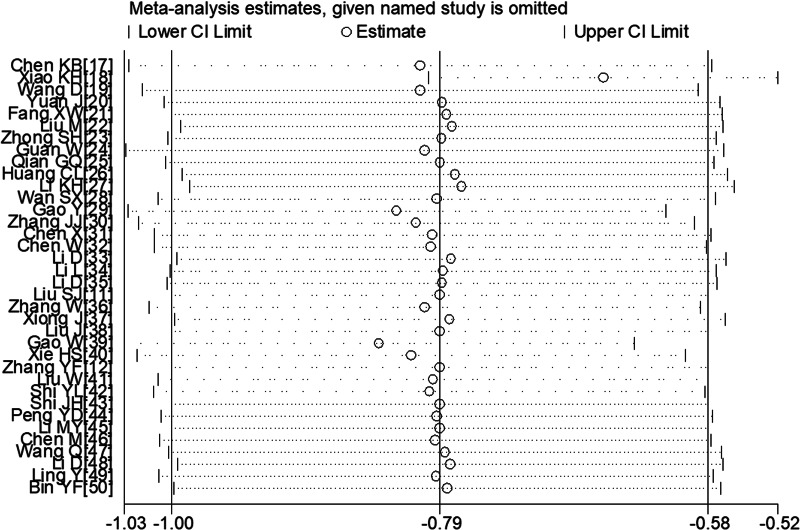

Sensitivity analysis

To determine sensitivity, we removed each study one by one and the pooled results did not change substantially, indicating the reliability and stability of our meta-analysis (e.g. Figure 7).

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis of the lymphocyte count between COVID-19 patients with or without severe disease.

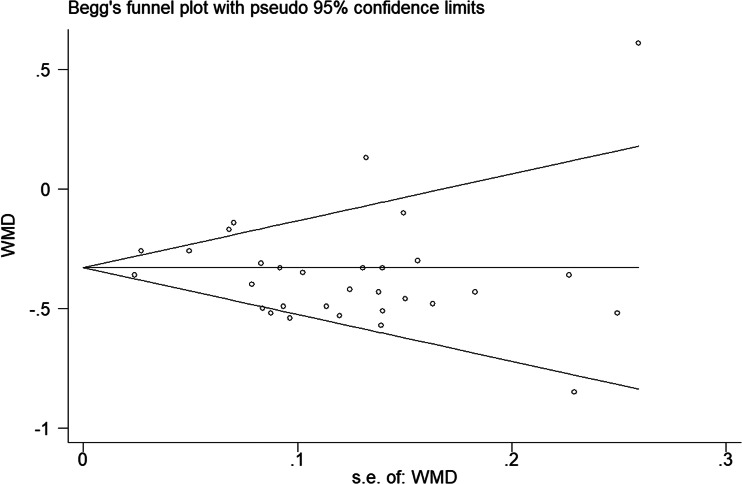

Publication bias

The P values derived using the Egger's and the Begg's test for all outcomes showed no obvious publication bias (Table 3). A funnel plot based on the outcome of lymphocyte count showed the P-values of Egger's and Begg's test were 0.315 and 0.919, respectively, indicating that the publication bias did not exist (Fig. 8).

Table 3.

Evaluation of publication bias using the Egger's and the Begg's test

| Group | Age | WBC | LBC | PLT | PCT | D-dimer | CRP | LDH | ALT | AST | Cr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-values of Egger's test | 0.167 | < 0.001 | 0.315 | 0.035 | < 0.001 | 0.072 | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.026 | 0.009 | 0.371 |

| P-values of Begg's test | 0.985 | 0.062 | 0.919 | 0.484 | 0.792 | 0.049 | 0.264 | 0.232 | 0.091 | 0.236 | 0.387 |

Fig. 8.

Funnel plot regarding the outcome of lymphocyte count.

Discussion

In this study, we meta-analysed the relevant literature from 1 January 2020. Our analysis of 40 studies [9–12, 15–50] involving 5872 COVID-19 patients suggests that lymphocyte and platelet count were found to be lower in those with severe disease than in those with mild disease, and significantly lower in those who die during follow-up than in those who survive. One plausible explanation is severely impaired immune function in severe cases, accompanied by lymphocyte necrosis and apoptosis, resulting in decreased lymphocytes in peripheral blood. According to the study by Zarychanski et al. [51], thrombocytopenia was commonplace in severe or critically ill patients, and usually suggests serious organ malfunction and may evolve towards disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC).

We also found that LDH, ALT, AST and Cr were higher in severe or death group, which suggested that the heart, liver, kidney and other important organ functions were more severely damaged in severe patients. Studies have shown that elevated levels of LDH was a risk factor for mild patients progressing to become critically ill patients [52] and the incidence of myocardial injury was greater in severe patients [45]. A recent meta-analysis included 341 COVID-19 patients, and the results showed that the values of cTnI were found to be significantly increased in COVID-19 patients with severe disease than in those without (SMD = 25.6, 95% CI 6.8–44.5) [53]. According to Xie et al. [40], liver injury was common in hospitalised COVID-19 patients, and it may be related to systemic inflammation. Therefore, intense monitoring and evaluation of liver function in COVID-19 patients should be considered. In addition, PCT and CRP were higher in the severe cases of this study. Since the production and release into the circulation of PCT from extrathyroidal sources is enormously amplified during bacterial infections [7], suggesting that severe cases were more likely to have a bacterial infection, so serial PCT measurement may play a role for predicting evolution towards a more severe form of the disease.

According to the study by Mahase [54], the overall fatality rate in COVID-19 patients has been estimated at 0.66%, rising sharply to 7.8% in people aged over 80 and declining to 0.0016% in children aged 9 and under. In Italy, the case-fatality rate even reached 20.2% in people aged over 80 [55]. In our study, severe patients were older compared to non-severe patients. These results suggest that older age is associated with an increased risk of death. The underlying reasons may be that older age had a more significant number of comorbid conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus, most of the chronic diseases share several standard features with infectious disorders, such as the proinflammatory state, and the attenuation of the innate immune response. Therefore, older age and comorbidities could be risk factors for severe patients.

Although our meta-analysis rigorously analysed data from a large sample of COVID-19 patients, our results are limited by the heterogeneity observed across studies. For example, given that most of the studies included in our meta-analysis were single-centre, retrospective studies, it was difficult for us to control for the effects of several confounding factors, including the disease course and severity, the participants' inclusion criteria as well as the studies design. Additionally, the studies included in our meta-analysis were from China, not those infected in other countries, so geographical and ethnic differences were not excluded whether the conclusion was consistent in other countries needs to be further investigated.

Conclusion

In summary, current evidence showed that, older age, low platelet count, lymphopenia, elevated levels of LDH, ALT, AST, PCT, Cr and D-dimer were associated with severity of COVID-19. And thus could be used as early identification or even prediction of worsening illness. Due to the limited quality and quantity of the included studies, more high-quality prospective studies are required to verify the above conclusions.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Emergency Science and Technology Brainstorm Project for the Prevention and Control of COVID-19, which is part of the Guangxi Key Research and Development Plan (Guike AB20058002).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.WHO. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. Available at https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 2.WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)Situation Report-75. Available at https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200404-sitrep-75-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=99251b2b_4 [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 3.WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Dashboard. Available at https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/685d0ace521648f8a5beeeee1b9125cd [Accessed 6 April 2020].

- 4.Yu J et al. (2020) Therapy for severe and critical corona virus disease 2019 and healthcare personnel protection. Shanghai Medical Journal. Published online: 23 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1366.R.20200320.1208.002.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Special expert group for control of the epidemic of novel coronavirus pneumonia of the Chinese Preventive Medicine Association (2020) An update on the epidemiological characteristics of novel coronavirus pneumonia COVID-19. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology 41, 139–144.32057211 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang X et al. (2020) Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. The Lancet. Respiratory Medicine 8, 475–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lippi G (2020) Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clinica Chimica Acta 505, 190–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lippi G et al. (2020) Thrombocytopenia is associated with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections: a meta-analysis. Clinica Chimica Acta 506, 145–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deng Y et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of fatal and recovered cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China: a retrospective study. Chinese Medical Journal 133, 1261–1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen T et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 368, m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu SJ et al. (2020) A study of laboratory confirmed cases between laboratory indexes and clinical classification of 342 cases with Corona virus disease 2019 in Ezhou. Laboratory Medicine. Published online: 2 April 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1915.r.20200401.1647.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y et al. (2020) Liver impairment in COVID-19 patients: a retrospective analysis of 115 cases from a single center in Wuhan city, China. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Apr 2]. Liver International: Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver. doi: 10.1111/liv.14455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stroup DF et al. (2000) Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA 283, 2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stang A (2010) Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. European Journal of Epidemiology 25, 603–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hozo SP et al. (2005) Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Medical Research Methodology 5, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou F et al. (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England) 395, 1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng KB et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 463 patients with common and severe type coronavirus disease 2019. Shanghai Medical Journal. Published online: 12 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1366.r.20200312.1254.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao KH et al. (2020) The clinical features of the 143 patients with COVID-19 in North-East of Chongqing. Journal of Third Military Medical University 42, 549–554. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang D et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA 323, 1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan J et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 223 novel coronavirus pneumonia cases in Chongqing. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition). Published online: 6 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/50.1189.N.20200305.1429.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang XW et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics and treatment analysis of 79 cases of COVID-19.Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin. Published online: 25 February 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/34.1086.r.20200224.1340.002.html. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu M et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 30 medical workers infected with new coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases 43, 209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong SH et al. (2020) The clinical characteristics and outcome of 62 patients with COVID-19. Medical Journal of Chinese People's Liberation Army. Published online: 26 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.1056.R.20200326.1308.002.html. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guan WJ et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirus infection in China. The New England Journal of Medicine 382, 1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qian GQ et al. (2020) Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics of 91 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Zhejiang, China: a retrospective, multi-centre case series. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians 113, 474–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang C et al. (2020) Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet (London, England) 395, 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li K et al. (2020) The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Investigative Radiology 55, 327–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan S et al. (2020) Clinical features and treatment of COVID-19 patients in northeast Chongqing. Journal of Medical Virology 92, 797–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao Y et al. (2020) Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. Journal of Medical Virology 92, 791–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang JJ et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 75, 1730–1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X et al. (2020) Retrospective study on the epidemiological characteristics of 139 patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia on the effects of severity. Chongqing Medicine. Published online: 13 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/50.1097.R.20200313.1537.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen W et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 91 novel coronavirus pneumonia patients in Jiangmen First People's Hospital. Journal of Inner Mongolia Medical University 42, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li D et al. (2020) Laboratory test analysisof sixty-two COVID-19 patients. Medical Journal of Wuhan University. Published online: 2 April 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/42.1677.r.20200401.1707.001.html. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li L et al. (2020) Traditional Chinese medicine characteristics of 46 patients with COVID-19. Journal of Capital Medical University. Published online: 2 April 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3662.R.20200401.1420.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li D et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 80 patients with COVID-19 in Zhuzhou city.Chinese Journal of Infection Control. Published online: 26 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/43.1390.R.20200324.1537.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang W et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 74 hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Journal of Capital Medical University. Published online: 2 April 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3662.r.20200401.1501.006.html. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiong J et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis in 89 cases of COVID-2019. Medical Journal of Wuhan University (Health Sciences) 41, 542–546. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J et al. (2020) Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 91 children conformed with COVID-19. Chinese Journal of Nosocomiology. Published online: 27 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3456.R.20200326.1721.007.html. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao W et al. (2020) Clinical characteristic of 90 patients with COVID-19 hospitalized in a grade-A hospital in Beijing. Academic Journal of Chinese PLA Medical School. Published online: 31 March 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/10.1117.R.20200330.1000.008.html. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie H et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of non-ICU hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 and liver injury: a retrospective study. Liver International: Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver 40, 1321–1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu W et al. (2020) Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chinese Medical Journal 133, 1032–1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi YL et al. (2020) Expressions of multiple inflammation markers in the patients with 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia and their clinical values. Chinese Journal of Laboratory Medicine 43, 346–351. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi JH et al. (2020) Digestive system manifestations and analysis of disease severity in 54 patients with corona virus disease 2019. Chinese Journal of Digestion 40, 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng YD et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 112 cardiovascular disease patients infected by 2019-nCoV. Chinese Journal of Cardiology 48, 450–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li MY et al. (2020) Analysis on the cardiac features of patients with different clinical types of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Guangdong Medical Journal 41, 797–800. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen M et al. (2020) Retrospective analysis of COVID-19 patients with different clinical subtypes. Herald of Medicine. Published online: 27 February 2020. Available at http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/42.1293.R.20200226.1852.004.html. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wan Q et al. (2020) Analysis of clinical features of 153 patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia in Chongqing. Chinese Journal of Clinical Infectious Diseases 13, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li D et al. (2020) Clinical features of 30 cases with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases 38, 204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ling Y et al. (2020) Clinical analysis ofrisk factors for severe patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Infectious Diseases 38, 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bin YF et al. (2020) Clinical characteristics of 55 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Journal of Guangxi Medical University 37, 338–342. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zarychanski R et al. (2017) Assessing thrombocytopenia in the intensive care unit: the past, present, and future. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program 2017(1), 660–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Phan LT et al. (2020) Importation and human-to-human transmission of a novel coronavirus in Vietnam. The New England Journal of Medicine 382, 872–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lippi G et al. (2020) Cardiac troponin I in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): evidence from a meta-analysis. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 63, 390–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mahase E. (2020) Covid-19: death rate is 066% and increases with age, study estimates. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 369, m1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Onder G et al. (2020) Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.