Abstract

The brain is considered an immune privileged site due to the high selectivity of the blood-brain barrier which restricts the passage of molecules and cells into the brain parenchyma. Recent studies have highlighted active immunosurveillance mechanisms in the brain. Here we review emerging evidence for the contribution of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) including natural killer (NK) cells to the immunosurveillance of brain cancers focusing on glioblastoma, one of the most aggressive and most common malignant primary brain tumors diagnosed in adults. Moreover, we discuss how the local tissue microenvironment and unique cellular interactions influence ILC functions in the brain and how these interactions might be successfully harnessed for cancer immunotherapy using insights gained from the studies of autoimmunity, aging, and CNS injury.

Keywords: clinical trial, immunotherapy, brain cancer, innate lymphoid cell, NK cell

Introduction

The global age-adjusted incidence of brain tumors is 5.57 per 100,000 people with over half being astrocytic tumors (1). Of astrocytomas, the most malignant form, glioblastoma (GBM), is diagnosed at a much higher frequency than lower grade astrocytomas. Even with an aggressive treatment regime, comprised of maximal safe resection, radiotherapy, and administration of the DNA alkylating agent, temozolomide (TMZ), the mean GBM survival time ranges between 12 and 15 months. Whilst recent advances in cancer immunotherapy have enhanced expectations for improved patient outcomes, current GBM treatment options remain limited and the mean overall survival of GBM patients has failed to improve over the last decade. The unique anatomy of the brain, the exclusive nature of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), and a poorly immunogenic, complex, and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) represent major challenges in treating malignant brain cancers. Here, we review emerging evidence for brain tumor immunosurveillance by NK cells and ILC subsets.

Natural Killer Cells

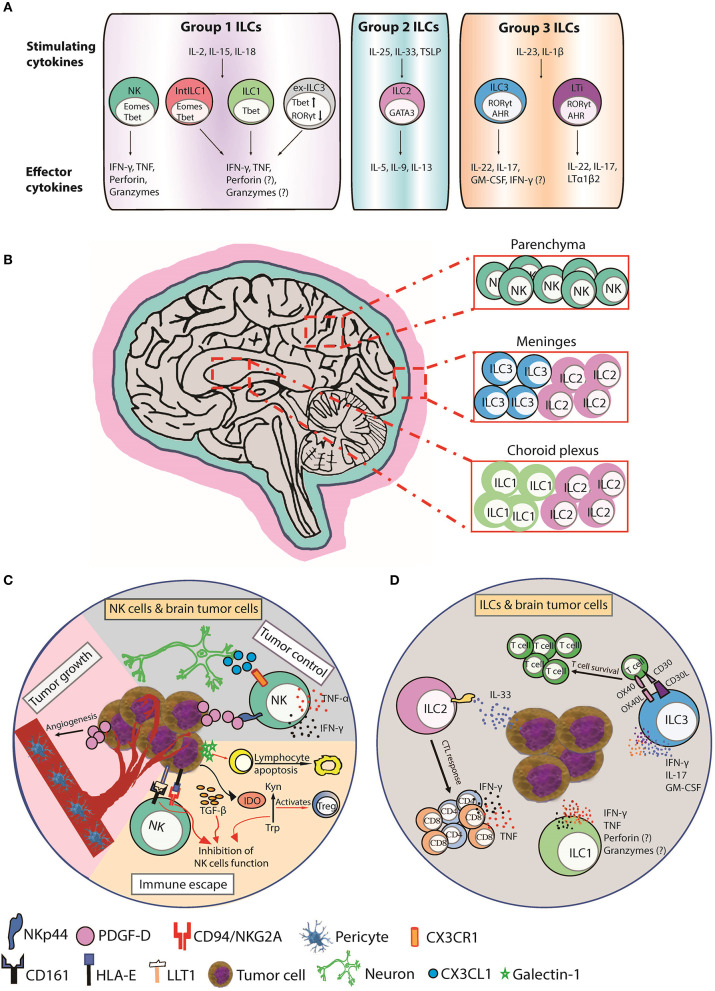

NK cells are large granular lymphocytes considered the innate counterparts of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) due to their spontaneous ability to lyse malignant and virus-infected cells, whereas ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3 mirror adaptive T helper subsets (Figure 1A). NK cells respond to “stressed” cells that downregulate MHC class I (MHCI) to evade CTL recognition and are therefore critical for anti-tumor immunity whenever CTL are compromised (3). NK cells are present at lower frequencies in the brains of naïve mice (4) (Figure 1B), but during neuropathological conditions, such as virus infection or autoimmunity, the BBB can become permeable, allowing NK cell migration into the CNS (5–9).

Figure 1.

Function, distribution, and anti-tumor responses of CNS ILC subsets. (A) Group 1 CNS ILCs have thus far been shown to include NK cells, intermediate ILC1s (intILC1s), ILC1s, and “ex-ILC3s.” NK cells express T-bet and Eomes and secrete IFN-γ and TNF in response to IL-2, IL-15, and IL-18, and lyse malignant cells via perforin, and granzymes. ILC1s express T-bet and produce IFN-γ and TNF in response to IL-2, IL-15, and IL-18 to promote type I immunity. Intermediate ILC1 (IntILC1) represent an intermediate phenotype between NK and ILC1 and express T-bet and Eomes. Ex-ILC3s are former ILC3 that have upregulated T-bet and downregulated RORγt to differentiate into ILC1-like cells. ILC2s express GATA3 and secrete IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 in response to IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP to promote type II immunity. Group 3 ILCs include ILC3s and LTi cells. ILC3s express RORγt and AHR and produce IL-17, IL-22, and GM-CSF in respond to IL-23 and IL-1β stimulation to counteract extracellular bacterial and fungal infections. LTi cells also express RORγt and AHR and produce IL-17, IL-22, and lymphotoxin (LTα1β2). LTi cells trigger lymphoid tissue organogenesis during development. (B) NK cells are mainly present in the brain parenchyma. ILC1s are enriched in choroid plexus, whereas ILC2s accumulate in the choroid plexus and meninges and ILC3s accumulate in the meninges. (C) CX3CR1+ NK cells can infiltrate the brain in response to CX3CL1 chemokine produced by neurons. (Tumor control) PDGF-D expressed by tumor cells binds to the activating NKp44 receptor expressed on activated NK and induces the secretion of IFN-γ and TNF that inhibits tumor cell proliferation. (Tumor growth) PDGF-D enhances tumor growth by promoting pericyte recruitment and tumor angiogenesis. (Immune escape) Tumor cells upregulate IDO, which inactivates NK cells and activates immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) by depletion of Trp and accumulation of Kyn. Tumor cells also secrete galectin-1 that induces lymphocyte apoptosis. Tumor cells supress NK cells function by inducing HLA-E and LLT1 ligands, which are ligands for NK cell inhibitory receptors CD94/NKG2A and CD161, respectively. TGF-β also inhibits NK cells function. (D) A hypothetical scheme showing the possible role of ILCs in brain cancer. Human ILC1s and ILC3s can express NKp44 and secrete IFN-γ and/or TNF in response to PDGF-DD to promote anti-tumor immunity (2). ILC2s enhance CTL responses to control the spread of tumors in response to IL-33 produced by tumor cells. ILC3s can also produce proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, IL-17, and GM-CSF and express the costimulatory molecules CD30L and OX40L that can promote T cell survival and function. AHR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocyte; EOMES, eomesodermin; GATA3, GATA-binding protein 3; GM-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IDO, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase; Kyn, kynurenine; LLT1, Lectin-like transcript-1; LTi, Lymphoid tissue-inducer; PDGF-D, Platelet Derived Growth Factor D; RORγt, retinoic acid-related orphan receptor gamma t; T-bet, T-box expressed in T cells; Trp, tryptophan; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin.

NK Cells in Brain Cancer

The CX3CL1 chemokine (also known as fractalkine) produced by neurons mediates CX3CR1+ NK cell recruitment to the brain and is associated with a favorable glioma prognosis (10) (Figure 1C). In one study, NK cells constituted the highest percentage of lymphocytes infiltrating GBM compared to breast cancers or melanomas suggesting a prominent role for NK cells in brain cancer surveillance (11). NK cells infiltrate meningiomas and metastatic brain neoplasms (12–14) and lyse GBM and medulloblastoma tumor cell-lines in vitro (15–22). NK cell receptors are linked with brain tumor surveillance and an allele of the activating KIR2DS4 receptor is associated with control of cytomegalovirus (CMV)-positive GBMs (23). CMV-induced expression of platelet-derived growth factor D (PDGF-D) enhanced GBM growth by promoting pericyte recruitment and tumor angiogenesis (24) (Figure 1C). PDGF-D is expressed by most GBMs and binds to the activating NKp44 receptor to stimulate cytokine secretion from NK cells and ILCs to control tumor growth, which was associated with improved survival of GBM patients (2) (Figure 1C). These studies implicate NK cells engage in brain tumor surveillance that impacts prognosis (14).

Several computational-based studies show that glioma patients expressing activated NK cell transcriptional signatures (TS) have improved prognosis (2, 25–29). Studies in patients and mouse models support these findings (10, 30, 31), with one human study showing a remarkable relationship between the presence of activated NK cells and improved survival in GBM (32). Another study showed that activated NK cells were higher in low grade compared to high grade gliomas suggesting reduction in activated NK cells is associated with transition from low to high grade brain cancers (27). NK cells may therefore play a detrimental role in brain tumor progression and heterogeneity. Expression of B7-H6, a ligand for the activating NKp30 receptor, is elevated in human glioma and associated with tumor progression (33). Whilst NK cells efficiently lyse undifferentiated GBM cancer stem cells (CSC), NK cell-derived IFN-γ promotes GBM CSC differentiation and decreased susceptibility to NK cell cytotoxicity (34, 35). In GBM, CSCs that survive therapy are a source of tumor recurrence/relapse. Influencing the balance of NK cell-mediated lysis of CSCs or opposing the pro-tumorigenic effect of NK cell-IFN-γ-induced CSC differentiation will be an important mechanism to decipher and target. Interestingly, IFN-γ-induced CSC differentiation concomitantly enhances tumor susceptibility to chemotherapy, suggesting NK cell-based therapies can be combined with other therapeutic strategies for more effective clinical outcomes (36, 37).

NK Cell-Based Immunotherapies for Brain Cancer

CNS tumors are often poorly immunogenic and highly immunosuppressive which imposes barriers to successful immunotherapy (38). A summary of current research and clinical trials into NK cell immunotherapies for malignant CNS tumors is provided (Table 1). Whilst NK cell cytotoxicity is facilitated by an array of activating receptors (62, 63) the chief inhibitory signal for NK cells, MHC class I (MHC-I), can be overexpressed in CNS malignancies and suppresses NK cell activity (64, 65). Strategies to enhance NK cell anti-tumor function include activating the DNA damage response (DDR) to induce ligands for activating NK cell receptors (66–68). The proteosomal inhibitor bortezomib (BTZ) activates the DDR and sensitizes GBM cells to NK cell killing by inducing ligands for the activating receptors, NKG2D (39, 59, 69, 70) and DNAM-1 (40). BTZ treatment with autologous NK cells suppressed tumor growth and prolonged survival in 25% of test animals (70). However, appropriate BTZ scheduling with NK cell transfer remains to be optimized to prevent sensitization of NK cells themselves (70). GBM patients have increased expression of NKG2D ligands (NKG2DL) following TMZ therapy and TMZ-induced activation of the DDR improved survival in a mouse model of GBM that was NKG2D-dependent (41).

Table 1.

Summary of current academic investigations and clinical trials into NK cell immunotherapy directed against malignant tumors of the CNS.

| Therapeutic Strategy | Treatment | Results summary | Model (tumor type) | Reference/Trial ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combinational therapy NK cells and chemotherapy | NK cells infusion with: Sulindac; MAPK and cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors (38) |

Reduces VEGF secretion and increases NK cell cytotoxicity; Suppresses tumor proliferation and increases NK cell cytotoxicity | Human (GBM, Lung cancer) | (37, 38) |

| Sensitization of tumors to NK cell cytotoxicity | NK cell infusion with BTZ |

Predisposes tumor to NK natural cytotoxicity and TRAIL/DR5; BTZ and NK cell infusion increased tumor elimination | Mouse (BG7); mouse (U87) | (39, 40) |

| Virotherapy | Triple therapy (NK cell infusion, BTZ, oHSV) | Tumor clearance tumor bearing mice; combinational therapy with BTZ and oHSV enhances tumor death and NK cell activation | Mouse (GBM30) | (41, 42) |

| TGF-β and oHSV infection | Modulated NK cell immune response to oHSV infected cells and improved anti-GBM effect of the oHSV treatment | Mouse (GB30) | (43) | |

| Overcoming immunosuppressive TME | siRNA interference of TGF-β signaling; infusion of TGF-β receptor negative NK cells | Reduction of tumorigenic profile of glioma; NK cells were resistant to TGF-β inhibition | Mouse (LNT229); in vitro; in vitro | (44–46) |

| Toll-like receptor agonism | CpG-ODN DNA TLR-9 agonism | Clinical trials failed to recapitulate results of encouraging in vitro TLR-9 agonism | Clinical trial (GBM); mouse (GL621) | (47–50) |

| Poly-ICLC TLR-3 agonism with bevacizumab (a-VEGF) | Poly-ICLC adjuvant to tumor associated antigens mixed with Bevacizumab—study unfinished, promising in vitro results | Human trial (GBM) | NCT02754362 (withdrawn—personnel changes) | |

| Directing NK cell immunity toward brain tumor antigens | Infusion of monalizumab (a-NKG2A)/cetuximab (a-EGFR) | NKG2A blockage potential to boost ADCC against GBM. Cetuximab treatment increased ADCC mediated by CD16+ NK cells (IL-2 or lectin-activated) | Human GBM stem cells in vitro | (51) |

| Infusion of CAR NKs engineered to be specific for EGFR, EGFRVIII, Erbb2 | EGFR, EGFRvIII CAR NK cells suppressed tumor growth and significantly prolonged survival; CXCR4 transduction enhanced antitumor responses of EGFR CAR NK cells; Erbb CAR NK cells | Mouse (GB19 xg); mouse (U87 xg); mouse (GL621 xg) | (52–54) | |

| Infusion of a-NG2/CSPG4 Ab | NK cell directed ADCC and proinflammatory tumor environment enhancing survival | Rat (U87); mouse (GBM) | (55, 56) | |

| Immune checkpoint blockade | Infusion of a-PD-1 and a-CTLA-4 Ab | Interference with peripheral immune cell inhibition potentiates intracranial immune response; immune checkpoint blockade antibodies improved survival in models | Mouse(GL621); mouse (B16) | (57, 58) |

| Blockade of interactions of HLA-E:CD94/NKG2A or LLT1/CD161 with siRNA or blocking Ab | Blockade promoted NK cell lysis | Human (GBM) in vitro | (59, 60) | |

| Circumventing the BBB | Infusion of a-CTLA-4/a-PD-1 Ab conjugated to biopolymer scaffold | Treatment able to cross BBB. Prolonged survival of mice compared to free a-CTLA-4 and a-PD-1 Ab | Mouse (GL261) | (61) |

| Autologous NK cell infusion expanded ex vivo | Artificial antigen-presenting cells | Promising in vitro, results forthcoming | Human trial (Recurrent MBM) | NCT02271711 (active) |

| Cytokines/Feeder cells + infusion recombinant human interleukin-15 | Promising in vitro, results forthcoming | Human (Solid brain tumors, SCM, NBM) | NCT01875601 (complete) | |

| Cancer/testis antigens presented by DNA-demethylated TH cells | Labeled cells infiltrated tumor site (SPECT imaging). Reduced disease burden 5 out of 10 patients. Long term survival in 3 of 10. However, slow kinetics of induced antitumor response | Human trial (GBM) | NCT01588769 (complete) | |

| Genetically modified feeder-cells | Promising in vitro, results forthcoming | Human trial (GBM) | NCT04254419 (not yet recruiting) | |

| Allogeneic (HLA)-haploidentical hematopoietic cell transplantation | Allo HTC and infusion with donor NK cells | Promising in vitro, results forthcoming | Human trial (eSCM, rSCM, oSCM, NBM) | NCT02100891 (recruiting) |

Abbreviated cancers: GBM, glioblastoma; MBM, medulloblastoma; NBM, neuroblastoma; e, Ewing; SCM, sarcoma; r, Rhabdomyosarcoma; o, Osteosarcoma. Other abbreviations: xg, Xenograft; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; BTZ, bortezomib; oHSV, oncolytic herpes simplex virus; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-beta; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; Ab, antibody.

Anti-cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, selective inhibitors of oncogenic signaling pathways, or oncolytic virotherapy can promote tumor cell death and enhance immunogenicity, which holds great potential when combined with immunotherapy (42, 71). Using a triple therapy approach, BTZ treatment combined with an oncolytic Herpes Simplex Virus (oHSV) strain sensitized GBM to adoptive NK cell therapy (40). BTZ enhanced expression of ligands for activating NK cell receptors, such as DNAM-1, whilst oHSV infection induced NK cell secretion of IFN-γ and TNF, which enhanced tumor cell death and improved survival of athymic nude mice transplanted with GBM tumors (40). Conversely, other studies claim NK cells limit oncolytic virotherapy by curbing virus infection of tumor cells. Transient TGF-β delivery or NK cell depletion increased oHSV titers, suppressed tumor growth, and prolonged survival in mouse GBM models (43, 72). TGF-β is considered a pro-tumor cytokine (73, 74) that suppresses NK cell function by downregulating activating NK cell receptors (75–77) or their ligands on brain tumor cells (78) (Figure 1C), reducing NK cell proliferation and converting NK cells into pro-tumor ILC1-like cells (79), or upregulating immunosuppressive extracellular matrix TME components, such as the galectins (44). Neutralizing TGF-β in the brain TME rescued NK cell anti-tumor function in glioma or medulloblastoma patients (45, 46) and expression of a dominant negative TGF-β receptor lacking the kinase domain (80) restored NK cell cytotoxicity against GBM and medulloblastoma cells in the presence of TGF-β in vitro (46, 81).

Brain tumors also secrete other soluble immunosuppressive factors, such as the carbohydrate-binding protein, galectin-1, that reduced lymphocyte viability (82) (Figure 1C). Galectin-1-deficient gliomas are more susceptible to NK cell lysis and were eradicated by NK cells before adaptive anti-tumor immune responses (17). Alternatively, glioma cells upregulate indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), a key rate-limiting enzyme of tryptophan (Trp) metabolism. IDO is involved in tumor-derived immunosuppression through Trp depletion and accumulation of the metabolite kynurenine that inactivated NK cells and promoted immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Tregs) (83) (Figure 1C).

Brain tumor cells also modulate their cell-surface to suppress NK cell function. Gain-of-function mutations in isocitrate dehydrogenases (IDH1 and IDH2) in diffuse gliomas promotes epigenetic reprogramming of a number of immune genes including NKG2DL downregulation and resistance to NK cell-mediated lysis (60). Decitabine (a hypomethylating compound) increased NKG2DL expression and restored NK cell-mediated lysis of IDH mutant cells in an NKG2D-dependent manner. In addition to downregulating activating NK cell surface interactions, brain tumors also promote inhibitory NK cell surface interactions. Malignant gliomas induce HLA-E or Lectin-like transcript-1 (LLT1), which can induce NK cell inhibition by binding CD94/NKG2A and CD161, respectively (51, 84–86) (Figure 1C). Blockade of HLA-E:CD94/NKG2A or LLT1/CD161 inhibitory interactions using small interfering RNA or blocking antibodies promoted NK cell lysis of glioma cells (65, 87). Interestingly, a humanized anti-NKG2A antibody, “monalizumab,” in combination with the anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) “cetuximab,” is effective in promoting antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against cetuximab-coated head and neck squamous carcinoma (88). EGFR is a prime target for therapy across a broad variety of tumor types including gliomas, suggesting NKG2A blockade with monalizumab has potential to boost NK cell-mediated ADCC against gliomas, particularly those resistant to TMZ (89).

Cancer adjuvants provide other means of reinvigorating anti-tumor immune responses. Oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated cytosine-guanosine motifs (CpG-ODNs) mimic pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) that bind to Toll-like Receptor 9 to induce type-I interferon (IFN-I) production from plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) (90). IFN-I enhances NK cell anti-tumor functions (47, 48) and CpG-ODN stimulation and Treg ablation unleashed NK cell cytotoxicity toward intracranial tumors (49). Despite encouraging results in vitro, human trials of CpG-ODN treatment in patients with primary (50) and recurrent GBM (52, 91) reported no benefit in CpG-ODN therapy, suggesting combination treatments are necessary, e.g., Treg depletion that may improve clinical responses. Intriguingly, depletion studies have implicated NK cells as the predominant anti-tumor effector cell in murine models of glioma following repeated low dose administration of CpG-ODN (53). However, tumor-infiltrating NK cells remained susceptible to suppression both locally and systemically, reinforcing the need for more effective methods of augmenting NK cell function in the brain TME.

Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs) are tumor-specific antibody single-chain variable fragments (scFvs) fused by a transmembrane linker domain to the CD3ζ signaling chain of the T cell receptor that can be transduced into autologous cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CAR T) or NK cells (CAR NK), respectively (54). CAR NK cells are attractive because they can be engineered to respond to a tumor antigen whilst retaining capacity for natural cytotoxicity. CAR NK cells directed toward EGFR or the constitutively activated mutant EGRFvIII GBM tumor antigen (55, 56) and ErbB2 (92) have shown potent cytotoxicity toward primary GBM tumor cells and cell lines in vitro. Some studies targeting GBM antigens show NK cells are important regulators of proinflammatory environments through IFN-γ secretion rather than cytotoxicity (57, 58). Transfer of NKG2D-CAR T cells combined with radiotherapy exhibited therapeutic synergy in mice bearing orthotopic tumors of the murine glioma cell line, GL261, although mice receiving intratumoral vs. intravenous CAR T cells were more likely to survive, reiterating the poor infiltration of intravenously administered CAR T cells into the brain parenchyma (61). Such studies highlight the need to develop immunological and mechanical adjuvants in concert with NK cell therapy to improve delivery to the brain parenchyma.

The BBB is a selectively permeable membrane that excludes harmful material from the parenchyma but impedes delivery of immunotherapeutic agents and cells to brain tumors. Anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 checkpoint blockade therapy increased NK cell and CD8+ T cell infiltration to the CNS and improved survival in models of GBM and melanoma brain metastases (93, 94). The conjugation of poly(β-L-malic) acid to anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 facilitated NK cell infiltration and survival in mice bearing intracranial GL261 tumors (95, 96). Combining these approaches with techniques to prolong persistence and enhance cytolytic potential of adoptively transferred NK cells may assist in overcoming the BBB and the immunosuppressive brain TME (97).

Group 1 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC1)

ILC1 express the transcription factor T-bet and secrete IFN-γ in response to IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18, facilitating control of intracellular pathogens by classical macrophage activation (98) or limiting local viral replication (99) (Figure 1A). It has been challenging to distinguish tissue ILC1s from NK cells because they share common functions and markers. The CNS contains NK cells, ILC1s, intermediate ILC1s, and “ex-ILC3” in the brain parenchyma, meninges, and choroid plexus (CP) (100). In contrast to CNS-NK cells, CNS-ILC1s are enriched in the CP (Figure 1B) (100). ILC1 functions in brain tumors awaits in depth evaluation but were investigated in the context of autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) (100). Steady-state CNS-NK cells and CNS-ILC1s expressed similar amounts of IFN-γ, whilst CNS-ILC1s produced more TNF. In EAE, NK cells had increased IFN-γ and TNF expression whilst ILC1s maintained stable levels. Interestingly, CNS-ILC1s from naïve and EAE mice express granzyme B and perforin and degranulated suggesting anti-tumor cytotoxic potential.

NK cells, ILC1s, and intermediate ILC1s accumulated in the brain parenchyma as EAE progressed. Unlike NK cells, ILC1s and intermediate ILC1s did not proliferate in situ, suggesting entry into the brain parenchyma via meninges or CP. ILC1 distribution and response during EAE strongly suggests they can regulate neuroinflammation. CNS-ILC1 were CD49a+CD49b− T-bet+Eomes− whilst CNS-NK cells were CD49a−CD49b+ T-bet+Eomes+. These markers provide a useful foundation to study ILC1 and NK cell contributions to anti-tumor immunity in mouse models of brain cancer. The dynamics and cytotoxic potential of ILC1s observed in the context of EAE suggests a potential role for CNS-ILC1s in restricting the growth of a brain tumors by lysing tumor cells or secreting immunoregulatory cytokines (100). NKp44 is also expressed by human ILC1 and ILC3 and activated by PDGF-DD, a pathway implicated in greater GBM survival (Figure 1D). It will be interesting to delineate the relative contributions of human ILC1, ILC3, or NK cells to anti-tumor immunity in brain cancers, such as GBM (2).

Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC2)

ILC2 express GATA3 and respond to IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) by secreting IL-5, IL-9, and IL-13 to promote type II immunity (Figure 1A) (101). ILC2s are found in large numbers in the meninges of naïve mice enriched around the dural sinuses (Figure 1B). After spinal injury, meningeal ILC2s are activated by IL-33 to produce IL-5 and IL-13 and partially improve recovery following spinal cord injury (102). ILC2s accumulate in the CP of aged mice and represent the major lymphocyte subset in aged mice and humans (103). ILC2s in the aged brain produced large amounts of IL-5 and IL-13 in response to IL-33. Treatment with IL-5 or IL-33 or adoptive transfer of activated ILC2s into the brain improved neurogenesis and cognitive function by reducing TNF secretion from brain-resident CD8+ T cells. ILC2s may therefore play a neuroprotective role by orchestrating appropriate CNS immune responses (Figure 1D).

Many reports suggest type-II immunity downregulates anti-tumor immunity by hindering CTL. Mice genetically lacking ILC2s had markedly increased tumor growth rates and higher frequencies of circulating tumor cells and brain metastases (1,000-fold) (104). Tumor cell-derived IL-33 stimulated IL-13 secretion by ILC2s that enhanced DC antigen presentation and generation of anti-tumor CTL. The authors proposed a model where ILC2s mobilized from the lungs and other tissues enter tumors at distal sites to engage in immunosurveillance (104). It will be interesting to determine the relative contribution of meningeal ILC2s or ILC2s mobilized from tissues, such as the lungs, in restricting brain metastases and tumor growth (102). Interestingly, the primary male sex hormone testosterone, influenced ILC2 numbers and function and promoted and sustained a non-pathogenic TH2 myelin-specific response in EAE. These results suggest sexual dimorphism in ILC2 numbers or function could influence ILC2 brain tumor surveillance in addition to GBM invasiveness (105, 106). The protective role of activated ILC2s that observed during CNS injury, EAE, and restriction of brain metastases, suggests a potential role for activated meningeal ILC2s in suppressing brain tumor progression by enhancing CTL activity in response to elevated levels of IL-33 that are observed in brain cancers, such as glioma (107).

Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells (ILC3)

ILC3 express RORγt and respond to IL-23 and IL-1β stimulation by secreting IL-17 and IL-22 that induce epithelial defense mechanisms and granulocytic responses to counteract extracellular bacterial and fungal infections (98) (Figure 1A). Lymphoid tissue-inducer (LTi) cells that trigger lymphoid tissue organogenesis during development are RORγt+ and produce IL-17 and IL-22 are categorized as ILC3 (Figure 1A) but emerge from the common lymphoid progenitor prior to ILCs (108). The role of ILC3 in brain cancer has not been extensively investigated. RORγt+ ILC3s are residents of the meninges in naïve B6 mice (109). LTi characteristically express c-Kit whereas expression of NKp46 differentiates ILC3 subtypes. A population of NKp46+CD4+ ILC3s was detected in the meninges but not in the CNS, whereas more c-Kit+ ILC3s were observed in the meninges than the CNS (Figure 1B).

In EAE, ILC3 numbers in the meninges and CNS increased. Meningeal ILC3s produced proinflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-17, and GM-CSF), and the costimulatory molecules (CD30L and OX40L) that promoted CD4+ memory T cell survival and function, which may impact the recognition of MHC class II-restricted neoantigens and response to immunotherapy TME (110). Moreover, c-Kit+ LTi cells, which can promote ectopic lymphoid follicle development, a hallmark of autoimmune diseases, were reduced in the meninges of EAE-resistant c-Kit mutant mice. Importantly, disease-induced trafficking of adoptively transferred wild type T lymphocytes to the meninges was impaired in ILC3-deficient Rorc−/− mice showing ILC3s sustain neuroinflammation by supporting T cell survival and reactivation in the meninges (Figure 1D).

Another study found T-bet-dependent NKp46+ ILCs, which encompass NK cells, ILC1, and the NKp46 subset of ILC3s, were localized to the meninges and produced various inflammatory mediators that disrupted the BBB and facilitated infiltration of myelin-reactive TH17 cells into the brain parenchyma (111). Selective loss of T-bet in NKp46+ ILCs resulted in the reduction of NK cells and ILC1s in the meninges and production of IFN-γ by NKp46+ ILC3s, which impaired TH17 invasion of the CNS and protected from EAE disease. Importantly, NK cell-sufficient and NK cell-deficient mice showed similar levels of paralysis, suggesting NK cells do not play a major role in EAE immunopathogenesis and the pathogenic role of T-bet maps to the NKp46+ ILC3s and/or ILC1. Collectively, these findings suggest meningeal ILC3s could promote anti-tumor immunity in brain cancer by facilitating the infiltration of T lymphocytes into the brain and supporting their survival. It will be interesting to determine if the NKp44+ cells located in the brain parenchyma and associated with improved survival in GBM are derived from meningeal ILC3 populations or from other regions of the brain (2) (Figure 1D).

Concluding Remarks

Transition of low-grade glioma to high-grade glioma, including transition to GBM, as well as post-treatment relapse remain major causes of treatment failure, and improved strategies to eradicate brain tumor cells are required. Understanding the functions of NK cells and ILCs in both healthy and tumorigenic brain is necessary for developing strategies for effective immunotherapy, including enhanced activation of brain resident NK cells and ILCs and transfusion and mobilization of engineered NK cells, e.g., CAR NK (112). Existing evidence, presented in this review, demonstrates a rapidly evolving NK cell and ILC research field and proposes that continued research efforts will lead to the development and refinement of NK- and ILC-based therapies which can be used in combination with existing standard and novel oncolytic virus and drug-based therapies to meaningfully enhance brain cancer patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

AS, NG, and PC drafted the manuscript. TM and AB critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved it for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was funded by the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) project APP1162217—Role of the NKP44-PDGF-DD immunosurveillance pathway in glioblastoma. AB is funded by MRFF grant APP1162217.

References

- 1.Leece R, Xu J, Ostrom QT, Chen Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. Global incidence of malignant brain and other central nervous system tumors by histology, 2003-2007. Neuro Oncol. (2017) 19:1553–64. 10.1093/neuonc/nox091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrow AD, Edeling MA, Trifonov V, Luo J, Goyal P, Bohl B, et al. Natural killer cells control tumor growth by sensing a growth factor. Cell. (2018) 172:534–48.e19. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu J, Hodgins JJ, Marathe M, Nicolai CJ, Bourgeois-Daigneault M-C, Trevino TN, et al. Contribution of NK cells to immunotherapy mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:4654–68. 10.1172/JCI99317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Korin B, Ben-Shaanan TL, Schiller M, Dubovik T, Azulay-Debby H, Boshnak NT, et al. High-dimensional, single-cell characterization of the brain's immune compartment. Nat Neurosci. (2017) 20:1300–9. 10.1038/nn.4610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lepennetier G, Hracsko Z, Unger M, Van Griensven M, Grummel V, Krumbholz M, et al. Cytokine and immune cell profiling in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neuro-inflammatory diseases. J Neuroinflammation. (2019) 16:219. 10.1186/s12974-019-1601-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kastrukoff LF, Lau AS, Takei F, Carbone FR, Scalzo AA. A NK complex-linked locus restricts the spread of herpes simplex virus type 1 in the brains of C57BL/6 mice. Immunol Cell Biol. (2015) 93:877–84. 10.1038/icb.2015.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owens GC, Garcia AJ, Mochizuki AY, Chang JW, Reyes SD, Salamon N, et al. Evidence for innate and adaptive immune responses in a cohort of intractable pediatric epilepsy surgery patients. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:121. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Gao Z, Wang D, Zhang T, Sun B, Mu L, et al. Accumulation of natural killer cells in ischemic brain tissues and the chemotactic effect of IP-10. J Neuroinflammation. (2014) 11:79. 10.1186/1742-2094-11-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Q, Sanai N, Jin W-N, La Cava A, Van Kaer L, Shi F-D. Neural stem cells sustain natural killer cells that dictate recovery from brain inflammation. Nat Neurosci. (2016) 19:243–52. 10.1038/nn.4211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren F, Zhao Q, Huang L, Zheng Y, Li L, He Q, et al. The R132H mutation in IDH1 promotes the recruitment of NK cells through CX3CL1/CX3CR1 chemotaxis and is correlated with a better prognosis in gliomas. Immunol Cell Biol. (2019) 97:457–69. 10.1111/imcb.12225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holl EK, Frazier VN, Landa K, Beasley GM, Hwang ES, Nair SK. Examining peripheral and tumor cellular immunome in patients with cancer. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:1767. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang I, Han SJ, Sughrue ME, Tihan T, Parsa AT. Immune cell infiltrate differences in pilocytic astrocytoma and glioblastoma: evidence of distinct immunological microenvironments that reflect tumor biology. J Neurosurg. (2011) 115:505–11. 10.3171/2011.4.JNS101172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domingues PH, Teodósio C, Ortiz J, Sousa P, Otero A, Maillo A, et al. Immunophenotypic identification and characterization of tumor cells and infiltrating cell populations in meningiomas. Am J Pathol. (2012) 181:1749–61. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Domingues P, González-Tablas M, Otero Á, Pascual D, Miranda D, Ruiz L, et al. Tumor infiltrating immune cells in gliomas and meningiomas. Brain Behav Immun. (2016) 53:1–5. 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sivori S, Parolini S, Marcenaro E, Castriconi R, Pende D, Millo R, et al. Involvement of natural cytotoxicity receptors in human natural killer cell-mediated lysis of neuroblastoma and glioblastoma cell lines. J Neuroimmunol. (2000) 107:220–5. 10.1016/S0165-5728(00)00221-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castriconi R, Daga A, Dondero A, Zona G, Poliani PL, Melotti A, et al. NK cells recognize and kill human glioblastoma cells with stem cell-like properties. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. (2009) 182:3530–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.0802845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baker GJ, Chockley P, Yadav VN, Doherty R, Ritt M, Sivaramakrishnan S, et al. Natural killer cells eradicate galectin-1-deficient glioma in the absence of adaptive immunity. Cancer Res. (2014) 74:5079–90. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haspels HN, Rahman MA, Joseph JV, Gras Navarro A, Chekenya M. Glioblastoma stem-like cells are more susceptible than differentiated cells to natural killer cell lysis mediated through killer immunoglobulin-like receptors-human leukocyte antigen ligand mismatch and activation receptor-ligand interactions. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1345. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castriconi R, Dondero A, Negri F, Bellora F, Nozza P, Carnemolla B, et al. Both CD133+ and CD133− medulloblastoma cell lines express ligands for triggering NK receptors and are susceptible to NK-mediated cytotoxicity. Eur J Immunol. (2007) 37:3190–6. 10.1002/eji.200737546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George RE, Loudon WG, Moser RP, Bruner JM, Steck PA, Grimm EA. In vitro cytolysis of primitive neuroectodermal tumors of the posterior fossa (medulloblastoma) by lymphokine-activated killer cells. J Neurosurg. (1988) 69:403–9. 10.3171/jns.1988.69.3.0403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kennis BA, Michel KA, Brugmann WB, Laureano A, Tao R-H, Somanchi SS, et al. Monitoring of intracerebellarly-administered natural killer cells with fluorine-19 MRI. J Neurooncol. (2019) 142:395–407. 10.1007/s11060-019-03091-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gras Navarro A, Kmiecik J, Leiss L, Zelkowski M, Engelsen A, Bruserud Ø, et al. NK cells with KIR2DS2 immunogenotype have a functional activation advantage to efficiently kill glioblastoma and prolong animal survival. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. (2014) 193:6192–206. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dominguez-Valentin M, Gras Navarro A, Rahman AM, Kumar S, Retière C, Ulvestad E, et al. Identification of a natural killer cell receptor allele that prolongs survival of cytomegalovirus-positive glioblastoma patients. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:5326–36. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krenzlin H, Behera P, Lorenz V, Passaro C, Zdioruk M, Nowicki MO, et al. Cytomegalovirus promotes murine glioblastoma growth via pericyte recruitment and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. (2019) 130:1671–83. 10.1172/JCI123375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vauléon E, Tony A, Hamlat A, Etcheverry A, Chiforeanu DC, Menei P, et al. Immune genes are associated with human glioblastoma pathology and patient survival. BMC Med Genomics. (2012) 5:41. 10.1186/1755-8794-5-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong Q-Y, Fan E-X, Feng G-Y, Chen Q-Y, Gou X-X, Yue G-J, et al. A gene expression-based study on immune cell subtypes and glioma prognosis. BMC Cancer. (2019) 19:1116. 10.1186/s12885-019-6324-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu J, Li H, Chen Z, Fan L, Feng S, Cai X, et al. Identification of 3 subpopulations of tumor-infiltrating immune cells for malignant transformation of low-grade glioma. Cancer Cell Int. (2019) 19:265. 10.1186/s12935-019-0972-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bockmayr M, Klauschen F, Maire CL, Rutkowski S, Westphal M, Lamszus K, et al. Immunologic profiling of mutational and transcriptional subgroups in pediatric and adult high-grade gliomas. Cancer Immunol Res. (2019) 7:1401–11. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu C, Zou C, Guan G, Guo Q, Yan Z, Liu T, et al. Development and validation of an interferon signature predicting prognosis and treatment response for glioblastoma. Oncoimmunology. (2019) 8:e1621677. 10.1080/2162402X.2019.1621677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SJ, Kang WY, Yoon Y, Jin JY, Song HJ, Her JH, et al. Natural killer (NK) cells inhibit systemic metastasis of glioblastoma cells and have therapeutic effects against glioblastomas in the brain. BMC Cancer. (2015) 15:1011. 10.1186/s12885-015-2034-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker GJ, Chockley P, Zamler D, Castro MG, Lowenstein PR. Natural killer cells require monocytic Gr-1(+)/CD11b(+) myeloid cells to eradicate orthotopically engrafted glioma cells. Oncoimmunology. (2016) 5:e1163461. 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1163461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mostafa H, Pala A, Högel J, Hlavac M, Dietrich E, Westhoff MA, et al. Immune phenotypes predict survival in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. J Hematol OncolJ Hematol Oncol. (2016) 9:77. 10.1186/s13045-016-0272-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang T, Wu W, Zhang H, Zhang X, Zhang D, Wang Q, et al. High expression of B7-H6 in human glioma tissues promotes tumor progression. Oncotarget. (2017) 8:37435–47. 10.18632/oncotarget.16391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tseng H-C, Inagaki A, Bui VT, Cacalano N, Kasahara N, Man Y-G, et al. Differential targeting of stem cells and differentiated glioblastomas by NK cells. J Cancer. (2015) 6:866–76. 10.7150/jca.11527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kozlowska AK, Tseng H-C, Kaur K, Topchyan P, Inagaki A, Bui VT, et al. Resistance to cytotoxicity and sustained release of interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 in the presence of decreased interferon-γ after differentiation of glioblastoma by human natural killer cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. (2016) 65:1085–97. 10.1007/s00262-016-1866-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kozlowska AK, Topchyan P, Kaur K, Tseng H-C, Teruel A, Hiraga T, et al. Differentiation by NK cells is a prerequisite for effective targeting of cancer stem cells/poorly differentiated tumors by chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic drugs. J Cancer. (2017) 8:537–54. 10.7150/jca.15989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruscetti M, Leibold J, Bott MJ, Fennell M, Kulick A, Salgado NR, et al. NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity contributes to tumor control by a cytostatic drug combination. Science. (2018) 362:1416–22. 10.1126/science.aas9090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Razavi S-M, Lee KE, Jin BE, Aujla PS, Gholamin S, Li G. Immune evasion strategies of glioblastoma. Front Surg. (2016) 3:11. 10.3389/fsurg.2016.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luna JI, Grossenbacher SK, Sturgill IR, Ames E, Judge SJ, Bouzid LA, et al. Bortezomib augments natural killer cell targeting of stem-like tumor cells. Cancers. (2019) 11:85. 10.3390/cancers11010085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yoo JY, Jaime-Ramirez AC, Bolyard C, Dai H, Nallanagulagari T, Wojton J, et al. Bortezomib treatment sensitizes oncolytic HSV-1-treated tumors to NK cell immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. (2016) 22:5265–76. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss T, Schneider H, Silginer M, Steinle A, Pruschy M, Polić B, et al. NKG2D-dependent antitumor effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy against glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. (2018) 24:882–95. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suryadevara CM, Riccione KA, Samspon JH. Immunotherapy gone viral: bortezomib and oHSV enhance antitumor NK-cell activity. Clin Cancer Res. (2016) 22:5164–6. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han J, Chen X, Chu J, Xu B, Meisen WH, Chen L, et al. TGFβ treatment enhances glioblastoma virotherapy by inhibiting the innate immune response. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:5273–82. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossi GR, Trindade ES, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F. Tumor microenvironment-associated extracellular matrix components regulate NK cell function. Front Immunol. (2020) 11:73. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Friese MA, Wischhusen J, Wick W, Weiler M, Eisele G, Steinle A, et al. RNA interference targeting transforming growth factor-beta enhances NKG2D-mediated antiglioma immune response, inhibits glioma cell migration and invasiveness, and abrogates tumorigenicity in vivo. Cancer Res. (2004) 64:7596–603. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powell AB, Yadavilli S, Saunders D, Van Pelt S, Chorvinsky E, Burga RA, et al. Medulloblastoma rendered susceptible to NK-cell attack by TGFβ neutralization. J Transl Med. (2019) 17:321. 10.1186/s12967-019-2055-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swann JB, Hayakawa Y, Zerafa N, Sheehan KCF, Scott B, Schreiber RD, et al. Type I IFN contributes to NK cell homeostasis, activation, and antitumor function. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. (2007) 178:7540–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Lou Y, Lizée G, Qin H, Liu S, Rabinovich B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce NK cell-dependent, tumor antigen-specific T cell cross-priming and tumor regression in mice. J Clin Invest. (2008) 118:1165–75. 10.1172/JCI33583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jarry U, Donnou S, Vincent M, Jeannin P, Pineau L, Fremaux I, et al. Treg depletion followed by intracerebral CpG-ODN injection induce brain tumor rejection. J Neuroimmunol. (2014) 267:35–42. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ursu R, Carpentier A, Metellus P, Lubrano V, Laigle-Donadey F, Capelle L, et al. Intracerebral injection of CpG oligonucleotide for patients with de novo glioblastoma-A phase II multicentric, randomised study. Eur J Cancer. (2017) 73:30–7. 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosen DB, Bettadapura J, Alsharifi M, Mathew PA, Warren HS, Lanier LL. Cutting edge: lectin-like transcript-1 is a ligand for the inhibitory human NKR-P1A receptor. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. (2005) 175:7796–9. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carpentier A, Metellus P, Ursu R, Zohar S, Lafitte F, Barrie M, et al. Intracerebral administration of CpG oligonucleotide for patients with recurrent glioblastoma: a phase II study. Neuro Oncol. (2010) 12:401–8. 10.1093/neuonc/nop047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alizadeh D, Zhang L, Brown CE, Farrukh O, Jensen MC, Badie B. Induction of anti-glioma natural killer cell response following multiple low-dose intracerebral CpG therapy. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res. (2010) 16:3399–408. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burger MC, Zhang C, Harter PN, Romanski A, Strassheimer F, Senft C, et al. CAR-engineered NK cells for the treatment of glioblastoma: turning innate effectors into precision tools for cancer immunotherapy. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2683. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han J, Chu J, Chan WK, Zhang J, Wang Y, Cohen JB, et al. CAR-engineered NK cells targeting wild-type EGFR and EGFRvIII enhance killing of glioblastoma and patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:11483. 10.1038/srep11483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Müller N, Michen S, Tietze S, Töpfer K, Schulte A, Lamszus K, et al. Engineering NK cells modified with an EGFRvIII-specific chimeric antigen receptor to overexpress CXCR4 improves immunotherapy of CXCL12/SDF-1α-secreting glioblastoma. J Immunother Hagerstown Md 1997. (2015) 38:197. 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Poli A, Wang J, Domingues O, Planagumà J, Yan T, Rygh CB, et al. Targeting glioblastoma with NK cells and mAb against NG2/CSPG4 prolongs animal survival. Oncotarget. (2013) 4:1527. 10.18632/oncotarget.1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kmiecik J, Gras Navarro A, Poli A, Planagumà JP, Zimmer J, Chekenya M. Combining NK cells and mAb9. 2.27 to combat NG2-dependent and anti-inflammatory signals in glioblastoma. Oncoimmunology. (2014) 3:e27185. 10.4161/onci.27185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hallett WH, Ames E, Motarjemi M, Barao I, Shanker A, Tamang DL, et al. Sensitization of tumor cells to NK cell-mediated killing by proteasome inhibition. J Immunol. (2008) 180:163–70. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X, Rao A, Sette P, Deibert C, Pomerantz A, Kim WJ, et al. IDH mutant gliomas escape natural killer cell immune surveillance by downregulation of NKG2D ligand expression. Neuro-Oncol. (2016) 18:1402–12. 10.1093/neuonc/now061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weiss T, Weller M, Guckenberger M, Sentman CL, Roth P. NKG2D-based CAR T cells and radiotherapy exert synergistic efficacy in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. (2018) 78:1031–43. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lanier LL. Up on the tightrope: natural killer cell activation and inhibition. Nat Immunol. (2008) 9:495–502. 10.1038/ni1581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barrow AD, Colonna M. The natural cytotoxicity receptors in health and disease. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:909. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Friese MA, Platten M, Lutz SZ, Naumann U, Aulwurm S, Bischof F, et al. MICA/NKG2D-mediated immunogene therapy of experimental gliomas. Cancer Res. (2003) 63:8996–9006. Available online at: https://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/63/24/8996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wischhusen J, Friese MA, Mittelbronn M, Meyermann R, Weller M. HLA-E protects glioma cells from NKG2D-mediated immune responses in vitro: implications for immune escape in vivo. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. (2005) 64:523–8. 10.1093/jnen/64.6.523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robison NJ, Yeo KK, Berliner AP, Malvar J, Sheard MA, Margol AS, et al. Phase I trial of dasatinib, lenalidomide, and temozolomide in children with relapsed or refractory central nervous system tumors. J Neurooncol. (2018) 138:199–207. 10.1007/s11060-018-2791-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soriani A, Zingoni A, Cerboni C, Iannitto ML, Ricciardi MR, Di Gialleonardo V, et al. ATM-ATR-dependent up-regulation of DNAM-1 and NKG2D ligands on multiple myeloma cells by therapeutic agents results in enhanced NK-cell susceptibility and is associated with a senescent phenotype. Blood. (2009) 113:3503–11. 10.1182/blood-2008-08-173914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gasser S, Orsulic S, Brown EJ, Raulet DH. The DNA damage pathway regulates innate immune system ligands of the NKG2D receptor. Nature. (2005) 436:1186–90. 10.1038/nature03884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernández L, Portugal R, Valentín J, Martín R, Maxwell H, González-Vicent M, et al. In vitro natural killer cell immunotherapy for medulloblastoma. Front Oncol. (2013) 3:94. 10.3389/fonc.2013.00094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gras Navarro A, Espedal H, Joseph JV, Trachsel-Moncho L, Bahador M, Tore Gjertsen B, et al. Pretreatment of glioblastoma with bortezomib potentiates natural killer cell cytotoxicity through TRAIL/DR5 mediated apoptosis and prolongs animal survival. Cancers. (2019) 11:996. 10.3390/cancers11070996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meisen WH, Kaur B. How can we trick the immune system into overcoming the detrimental effects of oncolytic viral therapy to treat glioblastoma? Expert Rev Neurother. (2013) 13:341–3. 10.1586/ern.13.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alvarez-Breckenridge CA, Yu J, Price R, Wojton J, Pradarelli J, Mao H, et al. NK cells impede glioblastoma virotherapy through NKp30 and NKp46 natural cytotoxicity receptors. Nat Med. (2012) 18:1827–34. 10.1038/nm.3013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Roy L-O, Poirier M-B, Fortin D. Transforming growth factor-beta and its implication in the malignancy of gliomas. Target Oncol. (2015) 10:1–14. 10.1007/s11523-014-0308-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Katz LH, Li Y, Chen J-S, Muñoz NM, Majumdar A, Chen J, et al. Targeting TGF-β signaling in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. (2013) 17:743–60. 10.1517/14728222.2013.782287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Crane CA, Han SJ, Barry JJ, Ahn BJ, Lanier LL, Parsa AT. TGF-β downregulates the activating receptor NKG2D on NK cells and CD8+ T cells in glioma patients. Neuro-Oncol. (2010) 12:7–13. 10.1093/neuonc/nop009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beier CP, Kumar P, Meyer K, Leukel P, Bruttel V, Aschenbrenner I, et al. The cancer stem cell subtype determines immune infiltration of glioblastoma. Stem Cells Dev. (2012) 21:2753–61. 10.1089/scd.2011.0660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Close HJ, Stead LF, Nsengimana J, Reilly KA, Droop A, Wurdak H, et al. Expression profiling of single cells and patient cohorts identifies multiple immunosuppressive pathways and an altered NK cell phenotype in glioblastoma. Clin Exp Immunol. (2020) 200:33–44. 10.1111/cei.13403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eisele G, Wischhusen J, Mittelbronn M, Meyermann R, Waldhauer I, Steinle A, et al. TGF-beta and metalloproteinases differentially suppress NKG2D ligand surface expression on malignant glioma cells. Brain J Neurol. (2006) 129:2416–25. 10.1093/brain/awl205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gao Y, Souza-Fonseca-Guimaraes F, Bald T, Ng SS, Young A, Ngiow SF, et al. Tumor immunoevasion by the conversion of effector NK cells into type 1 innate lymphoid cells. Nat Immunol. (2017) 18:1004–15. 10.1038/ni.3800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bollard CM, Rössig C, Calonge MJ, Huls MH, Wagner H-J, Massague J, et al. Adapting a transforming growth factor beta-related tumor protection strategy to enhance antitumor immunity. Blood. (2002) 99:3179–87. 10.1182/blood.V99.9.3179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yvon ES, Burga R, Powell A, Cruz CR, Fernandes R, Barese C, et al. Cord blood natural killer cells expressing a dominant negative TGF-β receptor: implications for adoptive immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Cytotherapy. (2017) 19:408–18. 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cedeno-Laurent F, Watanabe R, Teague JE, Kupper TS, Clark RA, Dimitroff CJ. Galectin-1 inhibits the viability, proliferation, and Th1 cytokine production of nonmalignant T cells in patients with leukemic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Blood. (2012) 119:3534–8. 10.1182/blood-2011-12-396457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hanihara M, Kawataki T, Oh-Oka K, Mitsuka K, Nakao A, Kinouchi H. Synergistic antitumor effect with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibition and temozolomide in a murine glioma model. J Neurosurg. (2016) 124:1594–601. 10.3171/2015.5.JNS141901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Braud VM, Allan DS, O'Callaghan CA, Söderström K, D'Andrea A, Ogg GS, et al. HLA-E binds to natural killer cell receptors CD94/NKG2A, B and C. Nature. (1998) 391:795–9. 10.1038/35869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee N, Llano M, Carretero M, Ishitani A, Navarro F, López-Botet M, et al. HLA-E is a major ligand for the natural killer inhibitory receptor CD94/NKG2A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (1998) 95:5199–204. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Aldemir H, Prod'homme V, Dumaurier M-J, Retiere C, Poupon G, Cazareth J, et al. Cutting edge: lectin-like transcript 1 is a ligand for the CD161 receptor. J Immunol Baltim Md 1950. (2005) 175:7791–5. 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.7791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Roth P, Mittelbronn M, Wick W, Meyermann R, Tatagiba M, Weller M. Malignant glioma cells counteract antitumor immune responses through expression of lectin-like transcript-1. Cancer Res. (2007) 67:3540–4. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.André P, Denis C, Soulas C, Bourbon-Caillet C, Lopez J, Arnoux T, et al. Anti-NKG2A mAb is a checkpoint inhibitor that promotes anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both T and NK cells. Cell. (2018) 175:1731–43.e13. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Meng X, Zhao Y, Han B, Zha C, Zhang Y, Li Z, et al. Dual functionalized brain-targeting nanoinhibitors restrain temozolomide-resistant glioma via attenuating EGFR and MET signaling pathways. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:594. 10.1038/s41467-019-14036-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Honda K, Ohba Y, Yanai H, Negishi H, Mizutani T, Takaoka A, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of MyD88-IRF-7 signalling for robust type-I interferon induction. Nature. (2005) 434:1035–40. 10.1038/nature03547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carpentier A, Laigle-Donadey F, Zohar S, Capelle L, Behin A, Tibi A, et al. Phase 1 trial of a CpG oligodeoxynucleotide for patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. (2006) 8:60–6. 10.1215/S1522851705000475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhang C, Oberoi P, Oelsner S, Waldmann A, Lindner A, Tonn T, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered NK-92 cells: an off-the-shelf cellular therapeutic for targeted elimination of cancer cells and induction of protective antitumor immunity. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:533. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Reardon DA, Gokhale PC, Klein SR, Ligon KL, Rodig SJ, Ramkissoon SH, et al. Glioblastoma eradication following immune checkpoint blockade in an orthotopic, immunocompetent model. Cancer Immunol Res. (2016) 4:124–35. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Taggart D, Andreou T, Scott KJ, Williams J, Rippaus N, Brownlie RJ, et al. Anti-PD-1/anti-CTLA-4 efficacy in melanoma brain metastases depends on extracranial disease and augmentation of CD8+ T cell trafficking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2018) 115:E1540–9. 10.1073/pnas.1714089115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Galstyan A, Markman JL, Shatalova ES, Chiechi A, Korman AJ, Patil R, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeable nano immunoconjugates induce local immune responses for glioma therapy. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:1–13. 10.1038/s41467-019-11719-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ding H, Portilla-Arias J, Patil R, Black KL, Ljubimova JY, Holler E. Distinct mechanisms of membrane permeation induced by two polymalic acid copolymers. Biomaterials. (2013) 34:217–25. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.08.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barrow AD, Colonna M. Tailoring natural killer cell immunotherapy to the tumour microenvironment. Semin Immunol. (2017) 31:30–6. 10.1016/j.smim.2017.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Barrow AD, Colonna M. Innate lymphoid cell sensing of tissue vitality. Curr Opin Immunol. (2018) 56:82–93. 10.1016/j.coi.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weizman O-E, Adams NM, Schuster IS, Krishna C, Pritykin Y, Lau C. ILC1 Confer early host protection at initial sites of viral infection. Cell. (2017) 171:795–808.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Romero-Suárez S, Del Rio Serrato A, Bueno RJ, Brunotte-Strecker D, Stehle C, Figueiredo CA, et al. The central nervous system contains ILC1s that differ from NK cells in the response to inflammation. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2337. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Klose CSN, Artis D. Innate lymphoid cells as regulators of immunity, inflammation and tissue homeostasis. Nat Immunol. (2016) 17:765–74. 10.1038/ni.3489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gadani SP, Smirnov I, Smith AT, Overall CC, Kipnis J. Characterization of meningeal type 2 innate lymphocytes and their response to CNS injury. J Exp Med. (2017) 214:285–96. 10.1084/jem.20161982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fung ITH, Sankar P, Zhang Y, Robison LS, Zhao X, D'Souza SS, et al. Activation of group 2 innate lymphoid cells alleviates aging-associated cognitive decline. J Exp Med. (2020) 217:e20190915. 10.1084/jem.20190915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Saranchova I, Han J, Zaman R, Arora H, Huang H, Fenninger F, et al. Type 2 innate lymphocytes actuate immunity against tumours and limit cancer metastasis. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:2924. 10.1038/s41598-018-20608-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Russi AE, Ebel ME, Yang Y, Brown MA. Male-specific IL-33 expression regulates sex-dimorphic EAE susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2018) 115:E1520–9. 10.1073/pnas.1710401115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rodríguez-Lozano DC, Piña-Medina AG, Hansberg-Pastor V, Bello-Alvarez C, Camacho-Arroyo I. Testosterone promotes glioblastoma cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through androgen receptor activation. Front Endocrinol. (2019) 10:16. 10.3389/fendo.2019.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang J-F, Wang P, Yan Y-J, Li Y, Guan M-W, Yu J-J, et al. IL-33 enhances glioma cell migration and invasion by upregulation of MMP2 and MMP9 via the ST2-NF-κB pathway. Oncol Rep. (2017) 38:2033–42. 10.3892/or.2017.5926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ishizuka IE, Chea S, Gudjonson H, Constantinides MG, Dinner AR, Bendelac A, et al. Single-cell analysis defines the divergence between the innate lymphoid cell lineage and lymphoid tissue-inducer cell lineage. Nat Immunol. (2016) 17:269–76. 10.1038/ni.3344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Hatfield JK, Brown MA. Group 3 innate lymphoid cells accumulate and exhibit disease-induced activation in the meninges in EAE. Cell Immunol. (2015) 297:69–79. 10.1016/j.cellimm.2015.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Alspach E, Lussier DM, Miceli AP, Kizhvatov I, DuPage M, Luoma AM, et al. MHC-II neoantigens shape tumour immunity and response to immunotherapy. Nature. (2019) 574:696–701. 10.1038/s41586-019-1671-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kwong B, Rua R, Gao Y, Flickinger J, Wang Y, Kruhlak MJ, et al. T-bet-dependent NKp46+ innate lymphoid cells regulate the onset of TH17-induced neuroinflammation. Nat Immunol. (2017) 18:1117–27. 10.1038/ni.3816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Barrow AD, Colonna M. Exploiting NK cell surveillance pathways for cancer therapy. Cancers. (2019) 11:55. 10.3390/cancers11010055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]