Abstract

Background

Acute soft tissue injuries are common and costly. The best drug treatment for such injuries is not certain, although non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are often recommended. There is concern about the use of oral opioids for acute pain leading to dependence. This is an update of a Cochrane Review published in 2015.

Objectives

To assess the benefits or harms of NSAIDs compared with other oral analgesics for treating acute soft tissue injuries.

Search methods

We searched the CENTRAL, 2020 Issue 1, MEDLINE (from 1946), and Embase (from 1980) to January 2020; other databases were searched to February 2019.

Selection criteria

We included randomised or quasi‐randomised controlled trials involving people with acute soft tissue injury (sprain, strain, or contusion of a joint, ligament, tendon, or muscle occurring within 48 hours of inclusion in the study), and comparing oral NSAIDs versus paracetamol (acetaminophen), opioid, paracetamol plus opioid, or complementary and alternative medicine. The outcomes were pain, swelling, function, adverse effects, and early re‐injury.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed studies for eligibility, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. We assessed the quality of the evidence using GRADE methodology.

Main results

We included 20 studies, with 3305 participants. Three studies included children only. The others included predominantly young adults; approximately 60% were male. Seven studies recruited people with ankle sprains only. Most studies were at low or unclear risk of bias; however, two were at high risk of selection bias, three were at high risk of bias from lack of blinding, and five were at high risk of selective outcome reporting bias. Some evidence relating to pain relief was high certainty. Other evidence was either moderate, low or very low certainty, reflecting study limitations, indirectness, imprecision, or combinations of these. Thus, we are certain or moderately certain about some of the estimates, and uncertain or very uncertain of others.

Eleven studies, involving 1853 participants compared NSAIDs with paracetamol. There were no differences between the two groups in pain at one to two hours (1178 participants, 6 studies; high‐certainty evidence), at days one to three (1232 participants, 6 studies; high‐certainty evidence), and at day seven or later (467 participants, 4 studies; low‐certainty evidence). There was little difference between the groups in numbers of participants with minimal swelling at day seven or later (77 participants, 1 study; low‐certainty evidence). Very low‐certainty evidence from three studies (386 participants) means we are uncertain of the finding of little difference between the two groups in return to function at day seven or later. There was low‐certainty evidence from 10 studies (1504 participants) that NSAIDs may slightly increase the risk of gastrointestinal adverse events compared with paracetamol. There was low‐certainty evidence from nine studies (1679 participants) of little difference in neurological adverse events between the NSAID and paracetamol groups.

Six studies, involving 1212 participants compared NSAIDs with opioids. There was moderate‐certainty evidence of no difference between the groups in pain at one hour (1058 participants, 4 studies), and low‐certainty evidence for no difference in pain at days four or seven (706 participants, 1 study). There was very low‐certainty evidence of no important difference between the groups in swelling (84 participants, 1 study). Participants in the NSAIDs group were more likely to return to function in 7 to 10 days (542 participants, 2 studies; low‐certainty evidence). There was moderate‐certainty evidence (1143 participants, 5 studies) that NSAIDs were less likely to result in gastrointestinal or neurological adverse events compared with opioids.

Four studies, involving 240 participants, compared NSAIDs with the combination of paracetamol and an opioid. The applicability of findings from these studies is in question because the dextropropoxyphene combination analgesic agents used are no longer in general use. Very low‐certainty evidence means we are uncertain of the findings of no differences between the two interventions in the numbers with little or no pain at day one (51 participants, 1 study), day three (149 participants, 2 studies), or day seven (138 participants, 2 studies); swelling (230 participants, 3 studies); return to function at day seven (89 participants, 1 study); and the risk of gastrointestinal or neurological adverse events (141 participants, 3 studies).

No studies reported re‐injury rates.

No studies compared NSAIDs with oral complementary and alternative medicines,

Authors' conclusions

Compared with paracetamol, NSAIDs make no difference to pain at one to two hours and at two to three days, and may make no difference at day seven or beyond. NSAIDs may result in a small increase in gastrointestinal adverse events and may make no difference in neurological adverse events compared with paracetamol.

Compared with opioids, NSAIDs probably make no difference to pain at one hour, and may make no difference at days four or seven. NSAIDs probably result in fewer gastrointestinal and neurological adverse effects compared with opioids.

The very low‐certainly evidence for all outcomes for the NSAIDs versus paracetamol with opioid combination analgesics means we are uncertain of the findings of no differences in pain or adverse effects.

The current evidence should not be extrapolated to adults older than 65 years, as this group was not well represented in the studies

Plain language summary

Oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs compared with other oral pain killers for sprains, strains and bruises

Introduction and aims

Sprains, strains, and bruises are common injuries, and people with these injuries often require pain relief, given as a tablet or capsule that is swallowed (oral). Many types of oral painkillers are available to treat such injuries. We wanted to know whether there were any differences in people's pain, swelling, function, or unwanted side effects when sprains, strains, and bruises were treated with oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, e.g. ibuprofen) compared with paracetamol, opioids (e.g. codeine), complementary or alternative medicines, or combinations of these.

This is an update of a Cochrane review published in 2015.

What did we do?

We searched medical databases up to January 2020 for studies that compared NSAIDs with other painkillers in people with sprains, strains, and bruises. Study participants could be any age. We assessed the included studies to judge the reliability (certainty) of the evidence. We categorised the evidence as being of high, moderate, low, or very low certainty. High certainty means we are confident in the evidence, moderate certainty means we are fairly confident, low or very low certainty means that we are unsure or very unsure of the reliability of the evidence.

Results of our search and description of studies

We included 20 studies, with 3305 participants. Seven studies included people with ankle sprain only. Three studies included children only. Most of the participants of the other studies were young adults, and there were slightly more men than women. Few participants were aged over 65 years. Eleven studies compared NSAIDs with paracetamol, six studies compared NSAIDs with opioids, and four studies compared NSAIDs with paracetamol combined with an opioid. Studies reported outcomes at times varying from one hour after taking the medication, up to 10 to 14 days.

Main results

There is no difference between NSAIDs and paracetamol in pain after one to two hours, or after two to three days (high‐certainty evidence), and there may be no difference after a week or more (low‐certainty evidence). There is low‐certainty evidence that NSAIDs may make little difference to swelling after a week or more. We are uncertain whether NSAIDs make a difference to return to function after a week or more (very low‐certainty evidence). There is low‐certainly evidence that NSAIDs may slightly increase unwanted side effects related to the gut.

There is probably no difference between NSAIDs and opioids in pain at one hour (moderate‐certainly evidence), and there may be no difference four or seven days after taking medication (low‐certainty evidence). We are uncertain whether NSAIDs make a difference to swelling after 10 days (very low‐certainty evidence). There is low‐certainty evidence that NSAIDs may increase return to function in 7 to 10 days. There is moderate‐certainty evidence that NSAIDs probably result in fewer unwanted side effects, such as nausea and dizziness, compared with opioids.

The evidence suggests that there is little or no difference between NSAIDs and paracetamol combined with opioids in pain, swelling, return to function, or unwanted side effects. However, the evidence was very low certainty, so we are uncertain of these results.

No studies reported the risk of re‐injury after treatment.

We found no studies comparing NSAIDs with complementary or alternative medicines.

Conclusions

The body of evidence to date has found no difference between NSAIDs and other pain killers for pain relief for strains, sprains, and bruises in younger people. However, we need more, and better evidence on return to function and unwanted side effects in all age groups, particularly in older people.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Acute soft tissue injuries are common; they cause 5% to 10% of emergency department attendances in the United Kingdom (Handoll 2007; Williams 1979). In Australia, over five million sports injuries occur annually (Cassell 2003; Medibank 2006), and in Germany, 3.1% of the population sustain a sports injury each year, most of which are acute soft tissue injuries (Schneider 2006).

The costs associated with these 'minor' injuries are substantial, with the lifetime cost of soft tissue injuries sustained in 2019 estimated at over $5 billion NZD in New Zealand (population: approximately five million; ACC 2020). The costs relate to treatment and time taken off work, with loss of income. Previously in the United Kingdom, lost productivity due to soft tissue injuries was estimated at over six million days/year (Nicholl 1995).

Acute soft tissue injuries include a number of conditions (sprain, strain, contusion, and haematoma) with similar well‐researched and understood pathology (Burke 2006). When the mechanical load on a tissue exceeds the tensile strength of the tissue, cell damage and haemorrhage occur. This initiates the inflammatory cascade (Burke 2006). Inflammation clears the necrotic cell debris after traumatic haemorrhage, providing a connective tissue framework for tissue regeneration (Martin 2005). Pain is the most common sequela of acute soft tissue injuries, and the main reason for the use of oral analgesics. Inflammation is the natural response to such injuries, and mediators of inflammation contribute to pain and swelling following injury. Inflammation and pain are worst in the first two days post‐injury, then decline rapidly (Almekinders 1986; Burke 2006; Obremsky 1994).

Description of the intervention

Analgesics are commonly prescribed, or used without prescription, for acute soft tissue injuries (Gøtzsche 2000; Motola 2004; Warner 2002). Traditional non‐selective non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the analgesic agents most often prescribed worldwide, as they have both analgesic and anti‐inflammatory effects (Gøtzsche 2000; Jones 1999; Motola 2004; Warner 2002). The use of NSAIDs for analgesia following an injury has been questioned, due to the high side effect profile of NSAIDs compared with that of other analgesic agents. For example, a short course (one week) of diclofenac has an associated mortality rate of 5.9 deaths per million users, compared with a rate of 0.2 per million users for paracetamol; thus, a nearly 30‐fold increased risk (Andrade 1998). The most common side effects of non‐selective NSAIDs are gastrointestinal. The incidence of these has been found to be twice as high in people receiving an NSAID for soft tissue injuries compared with a placebo (11% versus 5.5%); this equates to a number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) of 19 (95% confidence interval (CI) 11 to 43; Jones 1998). NSAIDs can cause acute renal failure (Pérez Gutthann 1996), bronchospasm, hypersensitivity reactions (Amadio 1997; Brooks 1991), and psychological decompensation (Browning 1996). They have also been implicated in necrotising fasciitis, with excess risk in the first month of treatment (Rietveld 1995). Further information on adverse effects can be found in Appendix 1.

Other oral analgesic agents in common use are paracetamol (acetaminophen), and oral opioids. Opioids and paracetamol have no direct peripheral anti‐inflammatory effects. Opioids act centrally and peripherally on opioid receptors for their analgesic efficacy and other effects (Pathan 2012). The exact mechanism of paracetamol remains unclear, but likely involves a number of inter‐related central pain pathways, including prostaglandin, serotinergic, nitric oxide, and cannabinoid pathways (Sharma 2013). Biologically active, oral complementary and alternative medicines (CAM), such as glucosamine, have also been studied in the setting of musculoskeletal pain. Glucosamine may have inhibitory effects on cytokines involved in inflammation (Haghighat 2013).

Recently, increasing use of a subclass of NSAIDs, the selective cyclooxygenase isoenzyme type 2 (COX‐2) inhibitors, and the centrally acting, oral opioid analgesic tramadol, has renewed interest in the topic of this review, with the publication of several trials of oral analgesics in acute soft tissue injuries in the last few years (Dalton 2006; Diaz 2006a; Ekman 2002a; Ekman 2006; Hewitt 2007; Nadarajah 2006a; Petrella 2004a). While the selective COX‐2 inhibitors have fewer gastrointestinal side effects compared with non‐selective NSAIDs, this may be at the cost of more cardiovascular side effects, particularly with long‐term use. Little is known about the cardiovascular risk with the short‐term use of selective COX‐2 inhibitors for acute soft tissue injury (Burke 2006; Chan 2006; Farkouh 2004; Kearney 2006; Schnitzer 2004).

How the intervention might work

The pain and swelling that result from injury are mediated by an inflammatory process (Burke 2006). The rationale for using NSAIDs for acute soft tissue injury is that pain and swelling are due to inflammation, so NSAIDs will improve symptoms because they reduce inflammation (Baldwin 2003; Ivins 2006; Mehallo 2006). However, there are counter‐arguments to the concept that NSAIDs improve healing. The first is that in this setting, inflammation is integral to the healing process, and by reducing inflammation, healing may be impaired (Major 1992; Paoloni 2005). The second is that NSAIDs delay, but do not reduce, the inflammatory response to injury (Almekinders 1986; Jones 1999). This means the putative benefit of using an NSAID for acute soft tissue injuries may not be realised.

We describe the common side effects of NSAIDs in the previous section. Opioids are known to cause sedation, respiratory depression, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diuresis, and dysphoria, depending on which opioid receptors are most stimulated (Pathan 2012). Paracetamol in prescribed doses has not been shown to have more adverse events than placebo, when used for up to three months for osteoarthritis, other than elevation of liver function tests in approximately five per cent of people (Leopoldino 2019). This is consistent with the known hepatoxicity of paracetamol when taken in overdose (Park 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

This is an update of a Cochrane Review first published in 2015 (Jones 2015). Prior to 2015, narrative reviews reached different conclusions; some recommended NSAIDs for acute soft tissue injuries (Baldwin 2003; Ivins 2006; Mehallo 2006); while others argued that they may be harmful (Jones 1999; Major 1992; Paoloni 2005). Some reviews found the evidence inconclusive (Gøtzsche 2000; Hertel 1997). Contributing to this uncertainty were conflicting reports of the effect of NSAIDs on inflammation in both animal and human models (Almekinders 1986; Almekinders 1995; Bogatov 2003; Obremsky 1994; Rahusen 2004), and a paucity of evidence that NSAIDs are superior to other analgesics in clinical studies (De Gara 1982a; Yates 1984a). These initial reviews were criticised on the basis of the poor quality of included studies, non‐systematic methods (CRD 2007), and variable outcome reporting that hindered meta‐analysis (Ogilvie‐Harris 1995). Athough we successfully addressed some of these concerns, the previous version of this review still found a paucity of available evidence, and imprecise results for some outcomes. There is recent concern that oral opioid prescription in the acute setting is increasing, and is associated with the development of opioid dependence (Barnett 2017). With the publication of new studies of oral analgesic agents for acute soft tissue injuries, it was timely to update this systematic review of NSAIDs compared with other analgesics for these injuries.

Objectives

To assess the effects (benefits and harms) of oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) compared with other oral analgesics for treating acute soft tissue injuries.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised (method of allocating participants to a treatment that is not strictly random, e.g. by date of birth, hospital record number, alternation) controlled trials comparing an oral non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drug (NSAID) with a different class of oral analgesic agent for the treatment of acute soft tissue injuries. We excluded cross‐over trials, which are inappropriate for short‐term conditions, and cluster‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

We included participants with an acute soft tissue injury. We defined this as follows:

soft tissue injury = sprain, strain, or contusion (haematoma) of a joint, ligament, tendon, or muscle; and

acute = injury occurring < 48 hours prior to inclusion in the study. We included studies with a clear majority of participants meeting this criterion (≥ 70%).

We had no restrictions based on age, sex, ethnicity, or study site.

We excluded studies if they focused on back pain, cervical spine injury, repetitive strain injuries, delayed onset muscle soreness, or primary inflammatory conditions (such as tendonitis or arthritis), as these conditions have either a different natural history, or reflect a different disease process.

Types of interventions

We considered oral analgesic agents commonly prescribed for treating acute soft tissue injuries, grouped by their local anti‐inflammatory effects.

We considered studies in which the intervention was to be completed within one month (30 days) of the injury, as by this time, most of the uncomplicated acute soft tissue injuries should have healed (Almekinders 1986; McClellan 2006). We included studies of oral NSAIDs versus oral comparators.

The groups for comparison were:

NSAID versus paracetamol (acetaminophen);

NSAID versus opioid;

NSAID versus combination analgesics (see below); and

NSAID versus complementary and alternative medicine; we planned to group these according to biological activity (Koithan 2009).

There are many combination analgesics containing different analgesics, with or without other agents (ANZCA 2005; Bandolier 2005). We grouped these analgesics according to anti‐inflammatory and opiate constituents if they were sufficiently similar (NSAID and opioid; NSAID and paracetamol; paracetamol and opioid; McNicol 2005). We only included comparisons of NSAID versus the paracetamol and opioid combination.

We excluded studies comparing COX‐2 selective NSAIDs versus non‐selective NSAIDs.

Types of outcome measures

When treating acute soft tissue injuries, pain, swelling, functional improvement, and adverse effects are of particular interest (Kellett 1986; Paoloni 2005; Weiler 1992). See Measures of treatment effect for further consideration on outcomes, including timing. More details of the measures listed below are provided in Measures of treatment effect.

We did not seek economic data for this review.

Primary outcomes

Pain

Our primary outcome measure was pain. Owing to its subjective nature, there is no standard method for reporting pain (IASP 2007). Consequently, different authors recorded pain in different ways, generally using categorical or visual analogue scales, and at different time points (Honig 1988).

Secondary outcomes

Swelling

We sought data for both subjectively reported and objectively measured swelling, which is considered a surrogate marker of inflammation. We collected both categorical and continuous data.

Function

We sought data for self‐reported assessment of function, functional impairment, and the proportion of people who had returned to function at prespecified time points.

Adverse effects

Potential adverse events of NSAIDs and other oral analgesics include gastrointestinal tract upset, renal disease, cardiovascular events, central nervous system side effects, respiratory depression, haematological abnormalities, skin photosensitivity, allergic reactions (rashes, throat swelling, wheeze, stridor), and necrotising fasciitis or soft tissue infections. We classified these events as serious if they led to death or admission to hospital (or the review authors thought it likely to lead to admission, if not stated in the report); required invasive intervention or monitoring (endoscopy, intermittent positive pressure ventilation, intramuscular or intravenous adrenalin); or needed resuscitation with crystalloid, colloid, or blood transfusion. We classed other adverse effects as minor.

Gastrointestinal adverse events were nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, peptic ulcer disease, gastrointestinal bleeding, hepatic dysfunction, diarrhoea, constipation, and other, if reported.

Neurological adverse effects were drowsiness or somnolence, dizziness or vertigo, headache, paraesthesia, seizure, and other, if reported.

Early re‐injury

We sought data on the recurrence of injury within three months, and time to re‐injury.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020 Issue 1) in the Cochrane Library (searched 29 January 2020); MEDLINE Ovid (Medline, Epub Ahead of Print, In‐process & Other non‐indexed citations, Daily and Versions; 1946 to 28 January 2020); Embase (1980 to 29 January 2020); Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; 1937 to 12 February 2019); Allied and Complementary Medicine (AMED; 1985 to 12 February 2019); International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (1970 to 12 February 2019); the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro; 1929 to 11 March 2019); and SPORTDiscus (1985 to 12 February 2019). The initial search was run in February 2019 for all databases, and a top‐up search was run in January 2020 in the three main databases: CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase. We did not place any restrictions based on language.

At the time of the search, CENTRAL was fully up‐to‐date with all records from the Bone Joint Muscle Trauma (BJMT) Group’s Specialised Register, and so it was not necessary to search this separately. For this update, we limited the searches were limited from the date of the previous searches to present: 2014 for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase, and 2012 for CINAHL, AMED, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, and SPORTDiscus. Details of the search strategies used for the previous review are given in Jones 2015.

We also searched trial registries, ClinicalTrials.gov (19 February 2019), and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry platform (WHO ICTRP; 18 February 2019), for ongoing and recently completed trials.

In MEDLINE, we combined the subject‐specific strategy with the sensitivity‐maximising version of the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials (Lefebvre 2011). See Appendix 2 for details of all search strategies.

Searching other resources

We handsearched the reference lists of retrieved articles. We contacted authors of retrieved studies to obtain relevant unpublished data, such as summary statistics if the published report did not contain these, or to ascertain whether a potentially relevant trial met the review inclusion criteria when this was unclear. We also contacted experts in the field and pharmaceutical companies to identify unpublished trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors, who were not blinded to trial authors or results, independently assessed studies for eligibility. They resolved any disagreement by discussion. Where necessary, we attempted to contact authors for further information. We saved details of searches (database, host, years covered, date and results) and present them in Appendix 2.

Data extraction and management

Using a piloted form, two review authors independently extracted data for the listed outcomes. They resolved discrepancies by consensus, or adjudication by a third review author. Where necessary, we contacted trialists for additional and missing data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias in the included studies using the 'Risk of bias' tool described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We graded each study's potential bias in each of the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (treatment providers, participants, outcome assessors), incomplete outcome data (pain, swelling, function, adverse effects), selective outcome reporting, and 'other'. For each study, we described the domains as reported (or after discussion with the trial authors), and judged their risk of bias. Our judgements were 'low', 'unclear' or 'high' risk of bias. We judged bias as 'unclear' if there was insufficient detail to make a judgement. The two review authors resolved disagreements regarding the risk of bias for domains by consensus.

Measures of treatment effect

Pain, swelling, and return to function are time dependent, as are the effects of the interventions (medicines with different times of onset and duration of effect). Therefore, we analysed these outcomes at different time intervals from the onset of treatment, based on the pathophysiology of acute soft tissue injury, and pharmacology of interventions discussed above, to minimise the 'effect modification' of time on pain and swelling (Glasziou 2002). If a trial did not report a relevant outcome at one of the specified time intervals, we did not include data from that study in the meta‐analysis. We used 95% confidence intervals (CI) throughout.

Primary outcome

Pain

Some trials reported pain on a continuous scale, others used a categorical scale, and some used both. We analysed the meta‐analysis of continuous and categorical pain outcomes separately.

Continuous data

For acute pain, a standard linear 10‐cm visual analogue scale (VAS‐10) has been shown to be a valid measurement tool, regardless of the severity of pain (Myles 1999; Myles 2005). In comparison, chronic pain has been shown to be non‐linear, possibly due to changes in the pain experience over time (Lund 2005; Quiding 1983; Svensson 2000; Williams 2000). The minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in acute pain scores using a 100‐mm VAS scale is 13 mm, regardless of age and baseline pain severity, equivalent to a one‐point change on a five‐point categorical scale (Barden 2004; Bijur 2003; Falgarone 2005; Fosnocht 2005; Gallagher 2001; Gallagher 2002; Kelly 1998; Kelly 2001; Lee 2003; Powell 2001; Salo 2003). However, a more clinically meaningful change for people is 30 mm (Bergh 2001; Farrar 2003; Jensen 2005; Lee 2003).

VAS‐10 scores are skewed. The skew shifts with time as pain subsides (Geraci 2007; Rosen 2000). This may invalidate summarising mean data from VAS‐10 scores using parametric methods, and there are currently no tools available to pool data using medians (Altman 2000; Geraci 2007; Quiding 1983). However, according to the Central Limit Theorem, the distribution of means of samples of a skewed distribution, will approximate normal for sample sizes over 15 (Kirkwood 2003). This has proven to be robust in computer simulations (Dexter 1995; Philip 1990).

We used mean differences (95% CI) to summarise VAS‐10 scores across studies. We carried out all analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

We derived dichotomous outcomes from VAS plots over time, a method developed to get around the issue of skew in single dose, postoperative pain studies (Moore 1996; Moore 1997). However, we considered this inappropriate for longer trials (Moore 2007), and now also consider it a poor reflection of the truth, even for single dose short‐term trials (Barden 2004).

Categorical data

For studies reporting analgesic effect using a categorical scale, we collapsed data into the proportion of participants experiencing 'good' or 'complete' pain relief, where possible. This method has previously been recommended to compare analgesics using five‐point scales (Moore 2005), as it facilitates analysis and interpretation, albeit at the cost of some lost information (Altman 2000; Cochrane 2002).

Similarly, if studies used different categorical scales, we collapsed them according to the following schedule.

3‐point: lowest two categories 'no pain relief', and one highest 'good pain relief'

4‐point: lowest three categories 'no pain relief', and one highest 'good pain relief'

5‐point: lowest three categories 'no pain relief', and two highest 'good pain relief'

6‐point: lowest four categories 'no pain relief', and two highest 'good pain relief'

7‐point: lowest four categories 'no pain relief', and three highest 'good pain relief'

8‐point: lowest five categories 'no pain relief', and three highest 'good pain relief'.

9‐point: lowest five categories 'no pain relief', and four highest 'good pain relief'.

10‐point: lowest six categories 'no pain relief', and four highest 'good pain relief'.

For all dichotomised data, we reported risk ratios (RR, 95% CI). We analysed outcomes on an intention‐to‐treat basis. For acute soft tissue injuries pain, RR is appropriate to report as event rates are high (typically > 50%) in this setting, and using odds ratios (OR) may lead to overestimation of the differences between interventions (Cukiernik 2007; Diaz 2006a).

We recognise that there are limitations of using RRs, which vary, depending on which intervention is chosen as the 'control', and are bounded by the event rate (Deeks 2001). Reflecting this lack of a standard approach (Deeks 2002), previous review authors have reported either OR or RR (Bandolier 2007; Manterola 2007; Wiffen 2005). Another alternative, risk difference (RD), depends on baseline risk, and is unlikely to be consistent between trials (Deeks 2001). We performed a sensitivity analysis for our results with RR by repeating the analysis with both OR and RD, checking for consistency, variance, and ease of interpretation (Deeks 2001; Deeks 2002).

Where trials reported categorical data as a mean with a standard deviation (SD), we only included studies with scales of 10 points or more (Bijur 2003; Herbison 2008).

We analysed pain at the following time points.

First 24 hours

Days one to three (the time of maximum pain related to acute injury (Jones 1998))

Days four to six (if reported (Jones 1998))

Days seven or more (pain expected to be minimal (Jones 1998), and analgesics often stopped (Kellett 1986))

Secondary outcomes

Swelling

We intended to combine trials that reported swelling using an objective measure, such as water displacement in mL, or circumference in cm (mean with SD given or calculable), in a meta‐analysis using the standardised mean difference (SMD, 95% CI). If trials reported subjective reduction in swelling, we treated this as dichotomised data.

We aimed to assess swelling at the following time points.

Day zero to three (bleeding due to initial tissue trauma)

Days four to six (maximum inflammatory response – data from animal studies)

Day seven or more (resolution of swelling in most cases)

Function

Where available, we presented data from self‐reported assessment of function and activities of daily living. However, the included trials usually reported function as 'Time to return of function' (from the time of injury to the time to return to full activity (work or sports)) and 'Functional impairment'. We dichotomised functional impairment on categorical scales, considering none or slightly clinically successful, and reported risk ratios (95% CI). If measured on a VAS, we calculated mean differences (95% CI). We took a difference of 15 mm to represent a clinically significant difference. We assessed 'Time to return to function' where possible, as proportions of people who had returned to function at the prespecified time intervals below.

Up to day seven

Days 7 to 14

After day 14

Adverse effects

We tabulated the presence or absence of major and minor adverse outcomes (described above) that occurred any time within three months (90 days) of the start of the study. We calculated risk ratios (95% CI).

Re‐injury

We intended to calculate risk ratios (95% CI) for the proportion of participants who reported that they had a recurrence of the index injury within three months. We planned to assess time to re‐injury, where possible, as the proportions of people who had re‐injured within the prespecified time intervals (up to day 15, days 15 to 30, after day 30); however, we found that included studies, or those retrieved for full text review, reported this outcome.

Unit of analysis issues

We did not include cluster‐randomised or cross‐over trials, a decision that minimised the unit of analyses issues in this review. We stratified analysis by different time points, to avoid the effect modification of time with respect to the outcomes measured. Some studies reported adverse effects at the event level rather than the participant level (some participants may have had more than one adverse event in the same system). We included data at the participant level, rather than the event level, in the analysis.

Multiple interventions

For trials investigating multiple interventions (for example, NSAID 1 versus NSAID 2 versus other analgesic), we combined the groups for comparison into a single pair‐wise comparison for the meta‐analysis (thus, NSAID 1 and NSAID 2 versus other analgesic), as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a).

Dealing with missing data

At the study level, we tried to ensure that we found all relevant studies by using a comprehensive search strategy. From study authors, we sought outcome data that studies measured but did not report. Where possible, we calculated missing standard deviations from other data, such as standard errors, exact P values, and 95% confidence intervals, when presented in the trial reports. Had we imputed data from other sources, we intended to perform a sensitivity analysis, by calculating the treatment effect including and excluding the imputed data, to see whether this would alter the outcome of the analysis.

Where studies reported adverse events at the event level for the broad categories of gastrointestinal and neurological adverse events, we used participant‐level data for the most common adverse event within the broad categories in the analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We displayed the results graphically, using forest plots with a summary statistic, in the absence of major clinical or statistical heterogeneity (lack of overlap of confidence intervals on the forest plots; Egger 2001; Egger 2001a). We assessed heterogeneity between trial results by examining the forest plots and calculating I² and Chi² statistics (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to assess reporting bias, using funnel plots when a single comparison included 10 or more studies (Higgins 2011b).

Data synthesis

We combined data using standard inverse variance methods and a fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We undertook subgroup analysis where there was disparity in the dosing of the drugs under comparison (e.g. one drug was given at standard dose and the other was given at less than standard dose):

insufficient dosing (less than maximum dose) of at least one comparator drug or relative dose discrepancy between comparators (i.e. one drug at low dose of therapeutic range and the other at maximal dose) versus

equivalent dosing of all comparator drugs (defined by national formulary of country of study, or British National Formulary, if this was not available).

Where there were sufficient numbers of trials, we undertook subgroup analysis by the analgesic comparator (paracetamol, opioid, paracetamol plus opioid).

We used the test for subgroup differences available in Review Manager 5 for the fixed‐effect model, to determine if the results for subgroups were conclusive (Review Manager 2014).

Where possible in future, we plan to undertake subgroup analyses based on NSAID categories (COX‐2 selective versus non‐selective NSAIDs), and age (< 18 years, 18 to 65 years, and > 65 years).

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses to explore the effects of different risks of bias associated with sequence generation (low or unclear versus high), allocation concealment (low or unclear versus high), and blinding (low versus unclear or high).

'Summary of findings' tables

We summarised the results for the three comparisons for which there were data in 'Summary of findings' tables: NSAIDs versus paracetamol, NSAIDs versus opioid, and NSAIDs versus paracetamol plus opioid. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of evidence related to seven key outcomes for each comparisons (Schünemann 2011). We used GRADEpro GDT to create the 'Summary of findings' tables and imported them into Review Manager 5 (GRADEpro GDT).

The outcomes were pain at < 24 hours; pain at 1 to 3 days (or 4 to 6 days if not available); pain at day 7 or later; swelling at day 7 or later; return to function at day 7 or later; gastrointestinal adverse events; and neurological adverse events. Although no studies reported on early re‐injury, we retained this as a key outcome, despite this increasing the number of outcomes to eight.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

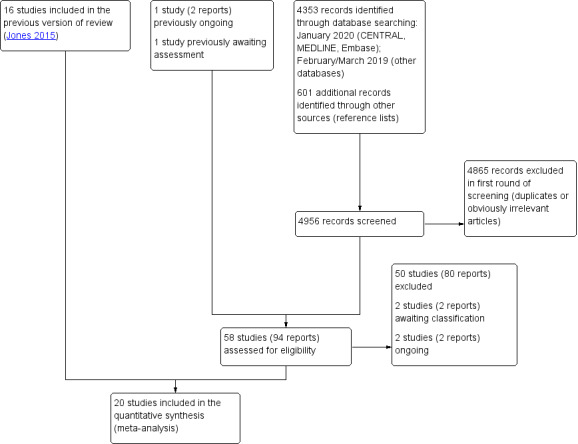

For this update, we screened a total of 4353 records from the following databases: CENTRAL (854), MEDLINE (518), Embase (675), CINAHL (125), AMED (44), SPORTDiscus (48), International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (51), PEDro (444), the WHO ICTRP (621), and ClinicalTrials.gov (973). We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and Embase to January 2020, and the other databases to February 2019. Our searches of other resources (reference lists) identified no additional studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria.

Once duplicates had been removed, we had a total of 2419 records. Two studies changed status since the previous version of this review. The PanAM study, which was ongoing in 2015, was published as Ridderikhof 2018, and 'Graham 2012', previously awaiting classification, has been published as Hung 2018.

We included four new trials Fathi 2015; Hung 2018; Le May 2017; Ridderikhof 2018, in addition to the previously included 16 trials (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Beveridge 1985; Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Dalton 2006; Ekman 2006; Indelicato 1986; Jaffé 1978; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004; McCulloch 1985; Woo 2005). We excluded another 50 studies (see Excluded studies), two studies are ongoing (see Ongoing studies), and two are awaiting classification (see Studies awaiting classification).

Figure 1 illustrates details of the process of screening and selecting studies for inclusion in the review (including the database search results from the previous publication; Jones 2015).

1.

Study flow diagram for update

Results of contacting authors

We attempted to contact trialists when we needed clarification on study eligibility criteria for the review, or published data were insufficient to include in the quantitative analysis. We considered the published data sufficient for inclusion in just one included study (Jaffé 1978). We were unable to find current contact details for four included studies (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Beveridge 1985; Indelicato 1986), and two excluded studies (Buccelletti 2014; De Gara 1982). We received no reply from authors of six included studies (Bourne 1980; Dalton 2006; Fathi 2015; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004). We received replies from authors of eight included studies, five of whom provided the requested data (Bondarsky 2013; Cukiernik 2007; Clark 2007; Le May 2017; Ridderikhof 2018), and three who reported that the study data were no longer available (Hung 2018; McCulloch 1985; Woo 2005). Notably, we received adverse events data from Clark 2007 subsequent to the finalisation of the 2015 version of this review; we added these data to the current version (2020). We received replies from authors of two excluded studies, Le May 2013 provided data, while Yates 1984 reported that the study data were no longer available. We had contacted one pharmaceutical company previously, but they did not provide data relevant to this review (Ekman 2006).

Included studies

The 20 trials included a total of 3305 participants, 3287 for whom data were available for at least one outcome. For each trial, we present a summary of the condition, comparison, number randomised, number analysed for the outcome 'pain', and the number included in at least one outcome Table 4. Participants of seven trials had acute ankle sprains, and those of Jaffé 1978 had either ankle or wrist sprains. The participants of the other 12 trials were being treated for a variety of conditions; these were either solely or mainly soft tissue injuries. In all except one study, it was clear or likely that the majority of participants had an acute soft tissue injury. Aghababian 1986 did not state this explicitly, and Fathi 2015 did not specify that 'acute' was < 48 hours; however, as the setting was an emergency department in both studies, we considered it most likely that this was the case. We provide a full description of individual studies in the Characteristics of included studies table.

1. Summary of key characteristics of the included trials.

| Study ID | Condition^ | Comparison | No. randomised | No. in analyses (pain) | No. in analyses (at least 1 outcome) |

| Abbott 1980 | Acute soft tissue injury (76%) | NSAID vs combined* | 98 | 98 | 98 |

| Aghababian 1986 | Ankle sprain | NSAID vs combined* | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Beveridge 1985 | Acute soft tissue injury | NSAID vs opioid | 68 | 0 | 63 |

| Bondarsky 2013 | Acute soft tissue injury (70%) | NSAID vs paracetamol | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Bourne 1980 | Acute soft tissue injury | NSAID vs paracetamol | 60 | 0 | 55 |

| Clark 2007 | Children: Acute soft tissue injury | NSAID vs paracetamol NSAID vs opioid | 72 68 |

72 68 |

72 68 |

| Cukiernik 2007 | Children: ankle sprain | NSAID vs paracetamol | 80 | 76 | 77 |

| Dalton 2006 | Ankle sprain | NSAID vs paracetamol | 260 | 204 | 260 |

| Ekman 2006 | Ankle sprain | NSAID vs opioid | 706 | 706 | 706 |

| Fathi 2015 | Acute soft tissue injury (>80%) | NSAID vs opioid | 150 | 150 | 150 |

| Hung 2018 | Acute soft tissue injury (86%) | NSAID vs paracetamol | 521 | 453 | 519 |

| Indelicato 1986 | Acute soft tissue injury (and back pain) | NSAID vs combined* | 50 | 0 | 50 |

| Jaffé 1978 | Ankle/wrist sprain | NSAID vs combined* | 52 | 51 | 51 |

| Kayali 2007 | Ankle sprain | NSAID vs paracetamol | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Le May 2017 | Children: Acute soft tissue injury | NSAID vs opioid | 134 | 134 | 134 |

| Lyrtzis 2011 | Ankle sprain | NSAID vs paracetamol | 90 | 86 | 90 |

| Man 2004 | Acute soft tissue injury (92%) | NSAID vs paracetamol | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| McCulloch 1985 | Ankle sprain | NSAID vs opioid | 86 | 0 | 84 |

| Ridderikhof 2018 | Acute soft tissue injury (96%) | NSAID vs paracetamol | 365 | 365 | 365 |

| Woo 2005 | Acute soft tissue injury (82%) | NSAID vs paracetamol | 206 | 206 | 206 |

| TOTAL | 8 = ankle (+ 1 wrist) sprain. Others included any acute soft tissue injury |

11 'vs paracetamol' 6 'vs opioid' 4 'vs combined' | 3368 | 2908 | 3287 |

^notes in brackets reflect trials in which a percentage of the population met the review inclusion criteria *combined = paracetamol plus opioid vs = versus

Five studies had three trial groups (Bondarsky 2013; Clark 2007; Hung 2018; Le May 2017; Ridderikhof 2018). The third group in three studies, Bondarsky 2013, Hung 2018, and Ridderikhof 2018, used a combination intervention of NSAID plus paracetamol, and Le May 2017 used a combination of NSAID plus opioid; we excluded these four groups from the review. Clark 2007 compared ibuprofen versus paracetamol versus codeine.

Ekman 2006,Man 2004, and Woo 2005 had four treatment groups; valdecoxib twice daily, valdecoxib once daily, tramadol, and placebo in Ekman 2006; and indomethacin, diclofenac, paracetamol, and a combination of diclofenac plus paracetamol in Man 2004 and Woo 2005. We merged data from the first two NSAID groups in the analyses for all three trials, and excluded the fourth group, either placebo or a combination of NSAID plus paracetamol, from all three trials.

We grouped the following description of studies by the comparisons listed in Types of interventions. There were no trials comparing NSAID versus complementary and alternative medicine. Note that Clark 2007 features in two comparisons: NSAID versus paracetamol, and NSAID versus opioid.

NSAID versus paracetamol

Eleven studies compared NSAID with paracetamol (Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Dalton 2006; Hung 2018; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018; Woo 2005). Data were available for analysis of at least one outcome for 1843 out of 1853 participants; Table 4.

One study received no funding (Woo 2005); two studies were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies (Bourne 1980; Dalton 2006); four studies were funded through competitive public good research grants (Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Hung 2018; Ridderikhof 2018); and four studies did not state the source of funding (Bondarsky 2013; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004). An author of one study was an employee of a pharmaceutical company (Dalton 2006); the authors of five studies declared no relevant interests (Clark 2007; Hung 2018; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018); and five studies made no statement of declaration of interests (Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Cukiernik 2007; Kayali 2007; Woo 2005).

Four studies, with 530 participants, studied exclusively ankle sprain (Cukiernik 2007; Dalton 2006; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011). The other seven studies included a mix of participants with mainly lower and upper extremity soft tissue injuries (Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Clark 2007; Hung 2018; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018; Woo 2005). Due to variable reporting in the studies, it was not possible to account for the exact numbers of participants with specific injuries in these studies; these included at least 77 participants with back or neck injuries, 66 with lacerations, and 70 with minor fractures (which were initially thought to be soft tissue injuries); injuries that were outside the criteria for the review, but whose data we were unable to disaggregate for analysis. Thus, we included the data from these participants (approximately 11%) in the review.

All studies reported the gender of the enrolled participants; 60% of participants were male. Participants of two studies (N = 152) were exclusively children aged 6 to 17 years (Clark 2007), and 8 to 14 years (Cukiernik 2007), with the remaining nine studies conducted exclusively in adults over 16 years of age. Two studies (N = 320), in which 80% of participants were white, reported ethnicity (Bondarsky 2013; Dalton 2006).

The studies took place in Canada (Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007); Greece (Lyrtzis 2011); Hong Kong (Hung 2018; Man 2004; Woo 2005); Turkey (Kayali 2007); the United Kingdom (Bourne 1980); the Netherlands (Ridderikhof 2018); and the USA (Bondarsky 2013; Dalton 2006). The studies were carried out in a variety of locations, including general practice, emergency departments, student health centres, research facilities, sports medicine clinics, orthopaedic clinics, urgent care facilities, and rheumatology clinics.

Five studies compared ibuprofen with paracetamol (Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Clark 2007; Dalton 2006; Hung 2018); one compared naproxen with paracetamol (Cukiernik 2007); three compared diclofenac with paracetamol (Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Ridderikhof 2018); and two separate studies, by the same group, compared indomethacin and diclofenac separately with paracetamol (Man 2004; Woo 2005). The doses of the medications varied across the studies. Submaximal dosing of paracetamol occurred in three studies (Bourne 1980; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011); and submaximal dosing of NSAID was present in two studies (Man 2004; Woo 2005). In Hung 2018, the initial dose was optimal for the analysis in the emergency department, but subsequent daily dosing was suboptimal.

All but one study reported suitable data for pain (Bourne 1980); three studies provided suitable data about swelling (Dalton 2006; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011); two provided suitable data on function (Bourne 1980; Cukiernik 2007); and 10 studies provided suitable data on adverse events for the meta‐analysis (Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Cukiernik 2007; Dalton 2006; Hung 2018; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018; Woo 2005).

NSAID versus opioid

Six studies compared NSAIDs with opioids (Beveridge 1985; Clark 2007; Ekman 2006; Fathi 2015; Le May 2017; McCulloch 1985). Data were available for analysis for at least one outcome for 1205 out of 1212 participants (Table 4).

One study received no funding (Fathi 2015); one was funded by a pharmaceutical company (Ekman 2006); two were funded through competitive public good research grants (Clark 2007; Le May 2017); and two studies did not state the source of funding (Beveridge 1985; McCulloch 1985). An author of one study was an employee of a pharmaceutical company (Ekman 2006); the authors of three studies stated no relevant interests (Clark 2007; Fathi 2015; Le May 2017); and two studies made no statement of declarations of interest (Beveridge 1985; McCulloch 1985).

Two studies, with 792 participants, exclusively considered ankle sprain (Ekman 2006; McCulloch 1985). Beveridge 1985 included participants with a mixture of lower extremity (53 participants) and 'other' sites (10 participants) of soft tissue injury. Fathi 2015 included 150 participants with a mix of injury types, including 26 with lumbosacral or intervertebral disc problems. Clark 2007 did not specify the site or type of injury. The study authors of Le May 2017, which included approximately 40% fractures, provided data to us on the 134 participants with soft tissue injuries in multiple sites separately for inclusion in this review.

Five of the studies reported the gender of participants. Slightly under 60% were male (Beveridge 1985; Clark 2007; Ekman 2006; Fathi 2015; Le May 2017). McCulloch 1985 reported no difference in the ratio of male and female, but provided no data. Two of the studies (N = 202) randomised exclusively children aged 6 to 17 years (mean age of 12 years; Clark 2007; Le May 2017), one of which only enrolled participants during the approximately 30 hours per week when research staff were available (Le May 2017). One study enrolled participants aged between 16 and 64 years, with a mean age of 29 years (Ekman 2006); one enrolled participants aged between 18 and 45 years (Beveridge 1985); and one study enrolled participants older than 18 years, with no upper age limit (Fathi 2015). One did not state an age restriction; the mean age of those enrolled in this study was 32 years (McCulloch 1985). Only Ekman 2006 reported ethnicity of participants; 80% were white, 8% black, 3% Asian, and 9% other.

Three of the studies were single‐centre emergency department studies: one in the United Kingdom (McCulloch 1985), one in Canada (Clark 2007), and one in Iran (Fathi 2015). Another Canadian study was a multicentre emergency department study (Le May 2017). The study by Beveridge 1985 took place at a football club in the United Kingdom. Ekman 2006 was a multicentre study with 14 European and 73 American sites; it did not state whether these were hospital‐based, emergency or orthopaedic departments, or primary care facilities.

Three studies compared naproxen with dextropropoxyphene (Beveridge 1985), dihydrocodeine (Fathi 2015), and oxycodone (McCulloch 1985). McCulloch 1985 reported a four‐arm factorial trial, simultaneously comparing plaster immobilisation to Tubigrip™ bandage, as well as NSAID versus opioid. Clark 2007 compared ibuprofen with codeine phosphate, and Le May 2017 compared ibuprofen to morphine. Ekman 2006 compared two doses of valdecoxib (selective COX‐2 inhibitor) separately with tramadol. Submaximal dosing of tramadol was present in one study (Ekman 2006).

Four studies reported data sufficiently to be pooled for the outcome of pain (Clark 2007; Ekman 2006; Fathi 2015; Le May 2017), one reported swelling (McCulloch 1985), two reported on function (Beveridge 1985; Ekman 2006), and four reported adverse events (Beveridge 1985; Ekman 2006; Fathi 2015; Le May 2017).

NSAID versus combination analgesics (combination of paracetamol and opioid)

Four studies compared NSAIDs with combined analgesics (paracetamol and an opioid; Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Indelicato 1986; Jaffé 1978). Data were available for analysis for at least one outcome for 239 out of 240 participants (Table 4).

Two studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies (Aghababian 1986; Indelicato 1986); two did not state the source of funding (Abbott 1980; Jaffé 1978). An author of one study was an employee of a pharmaceutical company (Jaffé 1978); the other three studies made no statement of declarations of interest.Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Indelicato 1986).

Aghababian 1986 studied only ankle sprains; Jaffé 1978studied ankle or wrist injuries; and there was a mix of injuries in the remaining two studies (Abbott 1980; Indelicato 1986). In total, 25 participants had ankle injuries; 25 had other lower extremity injuries; 37 had upper extremity injuries; and for 12 participants, the site was not specified. Some participants in two studies had back injuries or inflammatory conditions that were outside the criteria for the review (Abbott 1980; Indelicato 1986). Since separate outcome data for eligible participants were not available, we included the data from these participants (approximately 15% of study populations) in the review (seeDifferences between protocol and review).

All studies referred to the gender of the enrolled participants: 72% were male. The age range of participants was 16 years to 66 years. No study reported ethnicity data.

The studies took place in the UK (Abbott 1980; Jaffé 1978), and the USA (Aghababian 1986; Indelicato 1986). The studies were carried out in a variety of centres, including general practice, emergency departments, armed forces medical centres, and university sports clinics.

Two studies compared NSAIDs with a combination of paracetamol and dextropropoxyphene. The NSAID was diflunisal in Jaffé 1978, and naproxen in Abbott 1980. The other two studies compared a single NSAID (diflunisal) versus a paracetamol and codeine combination (Aghababian 1986; Indelicato 1986). The doses of the medications varied across the studies. All studies used combination analgesics that contained submaximal doses of paracetamol.

We included three of the four studies in the pain analyses (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Jaffé 1978). Data from Indelicato 1986 were unavailable for analysis because of the way in which the results were reported (for example, no standard deviations were reported for continuous outcomes, and we were unable to obtain separate data for acute soft tissue injuries). For similar reasons, we included data from Abbott 1980 only in the analyses for swelling and function. We pooled data on adverse events from all four studies.

Excluded studies

We grouped the 50 excluded studies initially by comparison, then by condition studied, and trial design. We provide more details of the reasons for excluding the studies in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

NSAID versus paracetamol

Five mixed population studies reported insufficiently separate data on relevant participants (Buccelletti 2014; De Gara 1982; Moore 1999; Patel 1993; Yates 1984). We attempted to contact study authors for additional information. One author replied (Yates 1984); however, the original study data were no longer available. One study, Yilmaz 2019, reported intravenous dosing of NSAIDs and paracetamol; a route that was not specified for this review .

NSAID versus opioid

One study reported insufficiently separate data for participants with relevant injuries (Pagliara 1997); the authors did not respond to a request for data. One study enrolled the majority of participants after 48 hours of injury (Goswick 1983).

NSAID versus combination analgesics (combination of paracetamol and opioid)

One study was not randomised (Stableforth 1977); we were unable to disaggregate data for participants with relevant injuries in the other six studies (Buccelletti 2014; Hardo 1982; Muncie 1986; Sherry 1988; Simmons 1982; Sleet 1980). The study authors did not respond to requests for more data.

NSAID plus other analgesic versus NSAID alone

Four studies (Kolodny 1975; Le May 2013; Turturro 2003; Yazdanpanah 2011), and one ongoing study (NCT03025113) compared a combination of NSAID plus another oral analgesic agent with NSAID alone; Kolodny 1975 was also not randomised.

NSAID plus other analgesic versus combination analgesics

We excluded two studies (Chang 2017; Graudins 2016), and three ongoing studies that compared NSAIDs in combination with another analgesic agent with different combinations of analgesic agents (NCT02862977; NCT03173456; NCT03767933).

COX‐2 selective NSAID versus non‐selective NSAID

We excluded 10 studies comparing a COX‐2 selective NSAID with a non‐selective NSAID, because they did not compare an NSAID versus another oral analgesic agent (Cardenas‐Estrada 2009; Cauchioli 1994; D'Hooghe 1992; Diaz 2006; Ekman 2002; Ferreira 1992; Jenoure 1998; Nadarajah 2006; Petrella 2004; Pfizer 2005). We excluded a further six studies considering this comparison for additional reasons (Calligaris 1993; Costa 1995; Dougados 2007; Jenner 1987; Kyle 2008; NCT00954785).

Placebo and other comparisons

We excluded two studies that compared NSAID with placebo (Andersson 1983; Jorgensen 1986), and one non‐randomised study that compared a biologically active CAM with placebo (Feragalli 2017). One other study compared an opioid with another non‐NSAID analgesic; this study was also not randomised (Khoury 2018).

Wrong condition

Two ongoing studies were excluded as they are not recruiting people with acute soft tissue injuries (NCT01974609; NCT02373254).

Not RCT

Five other studies were excluded as they were not randomised controlled trials (Collopy 2012; Gyer 2012; Jenner 1987; van den Bekerom 2016; Whitehead 2016)

Ongoing studies

We identified two ongoing studies comparing NSAID with paracetamol (NCT02667730; NCT03222518); see Characteristics of ongoing studies for further information.

Studies awaiting classification

One trial comparing ibuprofen to another medication may have been completed in 2010, but we do not know the class of the comparator medication. Only the trial registration is available for this study (CTRI/2009/091/001067). One trial that has not yet started recruiting plans to compare diclofenac with a plant extract for pain and adverse effects when treating acute muscle strain (TCTR20160126001); seeCharacteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 and Figure 3 summarise the risk of bias for the included studies.

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item for each included study

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each 'Risk of bias' item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

All 20 studies were randomised, although only eleven described an adequate method of sequence generation (Bondarsky 2013; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Ekman 2006; Fathi 2015; Hung 2018; Le May 2017; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018; Woo 2005). Eight studies did not state the method of sequence generation, so the risk of bias was unclear (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Beveridge 1985; Dalton 2006; Indelicato 1986; Jaffé 1978; Kayali 2007; McCulloch 1985). Bourne 1980 did not describe the method of sequence generation. We judged it at high risk of bias as "an attempt was made to pair the patients for site and type of injury"; and thus, it may have been a quasi‐randomised study.

Eight studies reported adequate allocation concealment, with the use of sealed, opaque, or unmarked envelopes, or identical packaging (Abbott 1980; Bondarsky 2013; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Ekman 2006; Hung 2018; Le May 2017; Ridderikhof 2018). One study reported the use of envelopes, but did not provide further details (Woo 2005), and one used envelopes, but the study tablets were not identical (Fathi 2015). In these studies, and the eight studies that did not report the method of allocation concealment, we considered the risk of bias unclear (Aghababian 1986; Beveridge 1985; Dalton 2006; Jaffé 1978; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011; Man 2004; McCulloch 1985). Given the pairing of participants for site and type of injury, Bourne 1980 clearly did not conceal allocation; thus, we judged it to be at high risk of selection bias. The other study at high risk for selection bias was Indelicato 1986, as it was an open‐label study.

Blinding

Eleven studies had adequate blinding of outcome assessors, participants, and treatment providers, and we judged them at low risk of performance and detection bias (Bondarsky 2013; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Dalton 2006; Ekman 2006; Hung 2018; Jaffé 1978; Le May 2017; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018; Woo 2005). We judged one study at low risk of bias for blinding of treatment providers and outcome assessors, although not for participants, as it did not blind them (Abbott 1980). Two studies blinded only the participants (Beveridge 1985; Bourne 1980), and McCulloch 1985 only blinded the outcome assessors. Four studies did not state the method of blinding, and we considered these to be at unclear risk of bias (Aghababian 1986; Fathi 2015; Kayali 2007; Lyrtzis 2011). Indelicato 1986 was an open‐label design, and at high risk of bias for blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed attrition bias separately according to the specific outcomes specified in the protocol of the review. Fifteen studies were at low risk of attrition bias across all outcomes they measured (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Beveridge 1985; Bondarsky 2013; Bourne 1980; Clark 2007; Dalton 2006; Ekman 2006; Fathi 2015; Indelicato 1986; Jaffé 1978; Le May 2017; Man 2004; Ridderikhof 2018). Cukiernik 2007 was at low risk for three outcomes, but at unclear risk for swelling, because it did not present these data in a format that allowed accurate abstraction. Hung 2018 was at low risk for the outcomes of pain and adverse effects in the emergency department; unclear for function, as this was not reported; and high for adverse effects at one month, as less than 50% were followed to this point. Lyrtzis 2011 was at low risk for two outcomes, and unclear risk for adverse events, because of incomplete reporting of these. Kayali 2007 was at unclear risk of bias because of not reporting the follow‐up rate. One study was at high risk of bias because of a disproportionate and high dropout rate between the groups (McCulloch 1985).

Selective reporting

Fourteen studies were at low risk of reporting bias (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Beveridge 1985; Bondarsky 2013; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Fathi 2015; Jaffé 1978; Kayali 2007; Le May 2017; Man 2004; McCulloch 1985; Ridderikhof 2018; Woo 2005). Lyrtzis 2011 was at unclear risk because of the way it described adverse effects. We considered five studies to be at high risk, either for not reporting all prespecified outcomes at the prespecified time points (Bourne 1980; Hung 2018; Indelicato 1986), or for selectively reporting only a proportion of adverse events (Dalton 2006; Ekman 2006).

Other potential sources of bias

We judged that the most likely other source of bias would be performance bias, reflecting imbalance between intervention groups in the use of concomitant physical (rest, ice, compression, elevation, splintage), or pharmacological therapies during the studies. We considered seven studies at low risk of other bias (Bourne 1980; Clark 2007; Cukiernik 2007; Dalton 2006; Ekman 2006; Lyrtzis 2011; Ridderikhof 2018).

Reflecting either no or incomplete accounts of treatment other than the interventions, we judged 12 studies to be at unclear risk of other bias (Abbott 1980; Aghababian 1986; Bondarsky 2013; Fathi 2015; Hung 2018; Indelicato 1986; Jaffé 1978; Kayali 2007; Le May 2017; Man 2004; McCulloch 1985; Woo 2005). We considered Beveridge 1985 to be at high risk of other bias because of the imbalance in the use of rehabilitation therapy (exercises) between the intervention groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3

Summary of findings 1. NSAID compared with paracetamol for acute soft tissue injury.

| NSAID compared with paracetamol for acute soft tissue injury | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with acute soft tissue injury, such as ankle sprain Setting: various outpatient locations (e.g. emergency department, student health centre) Intervention: NSAID Comparison: paracetamol | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with paracetamol | Risk with NSAIDs | |||||

|

Pain at < 24 hours (VAS: 0 to 100 mm: worst) Follow‐up: 1 to 2 hours |

The mean pain score ranged across paracetamol groups from 43 to 55 mm; and ‐12 to ‐19 mm mean reduction from baseline | The mean pain score in the NSAID groups was 0.12 mm lower (2.27 lower to 2.03 higher) | ‐ | 1178 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | All studies included mixed STI populations. The confidence interval did not reach the MCID (13 mm). |

|

Pain at days 1 to 3 (VAS: 0 to 100 mm: worst) Follow‐up: 2 to 3 days |

The mean pain score ranged across paracetamol groups from 11.9 to 36.7 mm; and ‐12.7 to ‐18.3 mm mean reduction from baseline | The mean pain score in the NSAID groups was 1.5 mm higher (0.91 lower to 3.91 higher) | ‐ | 1232 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ Higha | Two studies included ankle sprains and four included mixed STI populations. The confidence interval did not reach the MCID (13 mm). |

|

Pain on day 7 or later (VAS: 0 to 100 mm: worst) Follow‐up: 7 to 10 days |

The mean pain score ranged across control groups from 5.0 to 6.3 mm; with ‐54.4 mm mean reduction from baseline | The mean pain score in the NSAID groups was 1.55 mm higher (0.33 lower to 3.43 higher) | ‐ | 467 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | All four studies included ankle sprains; one included only children. The confidence interval did not reach the MCID (13 mm). |

|

Little or no swelling on day 7 or later Follow‐up: 10 days |

Study population | RR 0.84 (0.58 to 1.22) | 77 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | The study included children with ankle sprains only. This lack of difference was also found by two more studies (290 participants) involving ankle sprains that presented continuous (volume and VAS) data |

|

| 639 per 1000c | 537 per 1000 (371 to 779) | |||||

|

Return to function on day 7 or latere Follow‐up: 9 to 14 days |

Study population | RR 0.99 (0.90 to 1.09) | 386 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowg | Two studies included ankle sprains; one included children only, and one included a mixed STI population. | |

| 820 per 1000f | 812 per 1000 (738 to 894) | |||||

|

Gastrointestinal adverse events Follow‐up: 1 hour to 30 days |

Study population | RR 1.34 (0.97 to 1.86) | 1504 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowi | Four studies included ankle sprains, one included children only, and six included mixed STI populations. | |

| 75 per 1000h | 101 per 1000 (73 to 140) | |||||

| Neurological adverse events Follow‐up: 1 hour to 30 days | Study population | RR 0.85 (0.62 to 1.17) | 1679 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowj | Four studies included ankle sprains, one included children only, and five included mixed STI populations. | |

| 92 per 1000h | 78 per 1000 (57 to 108) | |||||

| Early re‐injury (within 3 months) | See comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MCID: minimal clinically important difference; RR: risk ratio; STI: soft tissue injury | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty. We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty. We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty. Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty. We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

a One study (100 participants) at unclear risk of bias across all domains slightly favoured paracetamol, while five others at low risk of bias did not. The evidence was not downgraded for risk of bias or inconsistency as including this study did not impact the finding of no statistically significant or clinically important difference b We downgraded the evidence by one level for study limitations (three studies were at unclear risk of several biases, including selection bias), and one level for indirectness reflecting suboptimal dosing of paracetamol in two studies (although these favoured paracetamol), and of both comparators in one study. Although there was inconsistency, reflecting statistically significant heterogeneity (P = 0.04; I² = 63%) of the pooled results, we did not consider this a reason to further downgrade the evidence, given the lack of clinical significance of the individual results of these studies c Assumed risk = control group risk in the study reporting this outcome d We downgraded the evidence by one level for study limitations (the sole study reporting this outcome was at unclear risk of bias relating to incomplete data for this outcome), and one level for imprecision (wide confidence intervals) e Function assessed differently in each study: numbers with no disability at day 14; numbers resuming sporting activity at day 10; and numbers who had resumed normal activity at day 9 f Assumed risk = median control group risk in the studies reporting this outcome g We downgraded the evidence by two levels for study limitations (one study was at high risk of selection bias and one at high risk of reporting bias), and one level for imprecision. Of note is the suboptimal dosing of paracetamol in one study, and of both comparators in another study. h Assumed risk = average risk for those in the paracetamol groups i We downgraded the evidence two levels for imprecision, as the lower confidence level just passed the point of no difference and the upper confidence level indicates an important difference j We downgraded the evidence two levels for imprecision, as the confidence interval was wide and included both benefit and harm

Summary of findings 2. NSAID compared with opioid for acute soft tissue injury.

| NSAID compared with opioid for acute soft tissue injury | ||||||

| Patient or population: acute soft tissue injury Setting: various outpatient locations (e.g. emergency department, sports club) Intervention: NSAID Comparison: opioid | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with opioid | Risk with NSAID | |||||

|

Pain at < 24 hours (VAS: 0 to 100 mm: worst) Follow‐up: 1 hour |

The mean pain score ranged across opioid groups from 13 to 27.7 mm | The mean pain in the NSAID group was 0.49 mm lower (3.05 lower to 2.07 higher) | ‐ | 1058 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | Three studies included a mixed STI population, one in children; the other study involved ankle sprains. The confidence interval did not include the MCID (13 mm). |

|

Pain at days 4 to 6 (VAS: 0 to 100 mm: worst) Follow‐up: 4 days |

The mean pain score in the opioid group was 31.8 mm | The mean pain in the NSAID group was 2.9 mm lower (6.06 lower to 0.26 higher) | ‐ | 706 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | There were no data for the earlier interim period (up to 3 days). The study included ankle sprains. The confidence interval did not include the MCID (13 mm). |

|

Pain on day 7 or later (VAS: 0 to 100 mm: worst) Follow‐up: 7 days |

The mean pain score in the opioid group was 15.1 mm | The mean pain in the NSAID group was 6.5 mm lower (9.31 lower to 3.69 lower) | ‐ | 706 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | The study included ankle sprains. The confidence interval did not include the MCID (13 mm). |

|

Little or no swelling on day 7 or later Follow‐up: 10 days |

Study population | RR 1.14 (0.61 to 2.13) | 84 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd | The study included ankle sprains | |

| 300 per 1000c | 342 per 1000 (183 to 639) | |||||

|

Return to function on day 7 or later (numbers returning to full function or returning to training) Follow‐up: 7 to 10 days |

Study population | RR 1.13 (1.03 to 1.25) | 749 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb | One study included ankle sprains, and one a mixed STI population. | |

| 664 per 1000e | 750 per 1000 (684 to 830) | |||||

|

Gastrointestinal adverse events Follow‐up: 2 hours to 14 days |

Study population | RR 0.48 (0.36 to 0.62) | 1151 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatef | Four studies included a mixed STI population, one in children; the other study involved ankle sprains. | |

| 205 per 1000e | 98 per 1000 (74 to 127) | |||||

|

Neurological adverse events Follow‐up: 2 hours to 14 days |

Study population | RR 0.40 (0.30 to 0.53) | 1151 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatef | Four studies involved a mixed STI population, one in children; the other study involved ankle sprains. | |

| 203 per 1000e | 81 per 1000 (61 to 108) | |||||

| Early re‐injury (with 3 months) | See Comment | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No study reported this outcome. | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MCID: minimal clinically important difference; RR: risk ratio; STI: soft tissue injury | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty. We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty. We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty. Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty. We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

a We downgraded the evidence one level for indirectness, 49% of the evidence and 67% of participants came from one study that used a COX‐2 selective NSAID that has been withdrawn from the market (Valdecoxib) b We downgraded the evidence two levels for indirectness, The evidence came from one study that used a COX‐2 selective NSAID that has been withdrawn from the market (Valdecoxib), and also used a suboptimal dose of opioid as a comparator c Assumed risk = control risk in this study d We downgraded the evidence by two levels for severe study limitations (the sole study reporting this outcome was at high risk of attrition bias relating to incomplete data for this outcome), and one level for imprecision (wide confidence interval) eAssumed risk = average control group risk in the studies reporting this outcome f We downgraded the evidence one level for indirectness, more than 80% of the evidence and 61% of participants came from one study that used a COX‐2 selective NSAID that has been withdrawn from the market (Valdecoxib)

Summary of findings 3. NSAID compared with combination (paracetamol and opioid) analgesic for acute soft tissue injury.

| NSAID compared with combination (paracetamol and opioid) analgesic for acute soft tissue injury | ||||||