Abstract

Background

Despite significant income-related disparities in pediatric sleep, few early childhood sleep interventions have been tailored for or tested with families of lower socio-economic status (SES). This qualitative study assessed caregiver and clinician perspectives to inform adaptation and implementation of evidence-based behavioral sleep interventions in urban primary care with families who are predominantly of lower SES.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with (a) 23 caregivers (96% mothers; 83% Black; 65% ≤125% U.S. poverty level) of toddlers and preschoolers with insomnia or insufficient sleep and (b) 22 urban primary care clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers, and psychologists; 87% female; 73% White). Guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, the interview guide assessed multilevel factors across five domains related to intervention implementation. Qualitative data were analyzed using an integrated approach to identify thematic patterns across participants and domains.

Results

Patterns of convergence and divergence in stakeholder perspectives emerged across themes. Participants agreed upon the importance of child sleep and intervention barriers (family work schedules; household and neighborhood factors). Perspectives aligned on intervention (flexibility; collaborative and empowering care) and implementation (caregiver-to-caregiver support and use of technology) facilitators. Clinicians identified many family barriers to treatment engagement, but caregivers perceived few barriers. Clinicians also raised healthcare setting factors that could support (integrated care) or hinder (space and resources) implementation.

Conclusions

Findings point to adaptations to evidence-based early childhood sleep intervention that may be necessary for effective implementation in urban primary care. Such adaptations could potentially reduce significant pediatric sleep-related health disparities.

Keywords: barriers, facilitators, implementation, primary care, sleep

Introduction

Sleep intervention in early childhood is critical given the high prevalence (20–30%) of sleep problems in young children (Mindell, Kuhn, Lewin, Meltzer, & Sadeh, 2006) and the many adverse outcomes linked to poor sleep (Beebe, 2011; Reynaud, Vecchierini, Heude, Charles, & Plancoulaine, 2018). There are significant income-related disparities in pediatric sleep patterns and problems beginning as early as 3 months of age (Grimes, Camerota, & Propper, 2019). Compared to youth of higher socio-economic status (SES) backgrounds, youth of lower SES have shorter sleep duration, poor sleep health behaviors (e.g., increased bedroom electronics), and greater insomnia symptoms, even when controlling for child race/ethnicity (El-Sheikh et al., 2013; Peña, Rifas-Shiman, Gillman, Redline, & Taveras, 2016), which is also associated with sleep disparities (Smith, Hardy, Hale, & Gazmararian, 2019).

There is a robust evidence base for the effectiveness of behavioral sleep interventions, particularly in early childhood (Meltzer & Mindell, 2014; Mindell et al., 2006). However, very few studies have examined intervention efficacy in families of lower SES or of racial/ethnic minority backgrounds (Schwichtenberg, Abel, Keys, & Honaker, 2019). Only two studies have examined sleep health education in children of lower SES (Mindell, Sedmak, Boyle, Butler, & Williamson, 2016; Wilson, Miller, Bonuck, Lumeng, & Chervin, 2014), but this research did not target children with sleep problems. Beyond sleep education, behavioral sleep interventions typically include caregiver-implemented components such as setting a consistent bedtime routine and sleep schedule, limit-setting around bedtime requests, and reducing caregiver presence at bedtime to promote independent sleep onset (Allen, Howlett, Coulombe, & Corkum, 2016; Mindell et al., 2006). Much like adaptations made to behavioral parent training, behavioral sleep interventions may require tailoring in content (intervention components), format (materials), and delivery for families of sociodemographically diverse backgrounds (Schwichtenberg et al., 2019). For families of lower SES backgrounds, caregiver shiftwork, parenting stress, a single caregiver household, lower health literacy, and transportation and childcare limitations may impact intervention access, engagement, and efficacy (Bathory et al., 2016; Ofonedu, Belcher, Budhathoki, & Gross, 2017; Walton, Mautone, Nissley-Tsiopinis, Blum, & Power, 2014).

Socio-cultural variation in sleep-related beliefs and practices may also impact intervention acceptability. For instance, bed- and room-sharing, which is more common in families of lower SES and may be due to limited economic resources or cultural factors (Mileva-Seitz, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Battaini, & Luijk, 2017), may not easily align with interventions designed to promote independent child sleep onset (Allen et al., 2016). Studies using qualitative methods have explored child sleep beliefs, practices, and healthy sleep barriers (e.g., overcrowded homes; work schedules) in immigrant Brazilian mothers of preschoolers (Lindsay, Moura Arruda, Tavares Machado, De Andrade, & Greaney, 2018), mothers of lower SES (Caldwell, Ordway, Sadler, & Redeker, 2020), and caregivers of toddlers with sleep problems (Sviggum, Sollesnes, & Langeland, 2018). However, research has yet to examine caregiver perspectives on behavioral interventions in children of lower SES with known sleep problems.

Furthermore, few studies have identified how to best implement behavioral sleep interventions in accessible settings such as primary care, which can support intervention scalability and dissemination (Parthasarathy et al., 2016). With a growing number of behavioral health providers integrated in primary care (Miller, Petterson, Burke, Phillips Jr, & Green, 2014) and frequent well visits in early childhood, implementing early childhood behavioral sleep intervention in primary care could reduce treatment barriers (Honaker & Meltzer, 2016). While cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with insomnia has been adapted for primary care (Troxel, Germain, & Buysse, 2012), research on addressing child sleep in primary care is limited to a feasibility study of sleep screening and provision of initial sleep recommendations by behavioral health clinicians (Honaker & Saunders, 2018). To address the ongoing research-to-practice gap in sleep (Parthasarathy et al., 2016), more research is needed on how to adapt and implement efficacious and scalable interventions in primary care.

Current Study

The purpose of this study was to assess stakeholder perspectives to inform adaptation and implementation of evidence-based behavioral sleep interventions in urban primary care. We qualitatively evaluated perspectives from stakeholders who would be impacted if we were to implement evidence-based behavioral sleep interventions in this context (a) caregivers of predominantly lower SES backgrounds with young children experiencing behavioral sleep problems and (b) clinicians (physicians, nurse practitioners, social workers, and psychologists) at urban primary care sites. In particular, we solicited information about factors that could support (facilitators) or hinder (barriers) intervention implementation in urban primary care.

Methods

Participants

All participants were recruited from three urban primary care sites that serve primarily Medicaid-insured patients and are affiliated with a large northeastern children’s hospital. Qualitative data saturation determined the sample size of 23 caregivers and 22 primary care clinicians. All clinicians at the urban primary care sites were informed about the study and asked to refer any potential caregiver participants they encountered during routine clinical care with a child ages 2–5 years with a sleep problem. The study team also recruited potential participants by reviewing child electronic health records (EHRs) and contacting caregivers of children ages 2–5 years scheduled for well-child or follow-up visits at the primary care sites. All potentially eligible caregivers were contacted to initiate study eligibility screening using a study screening form. Eligibility criteria were: English-speaking caregiver, age 18 or older, who was the legal guardian of a child ages 2–5 years receiving care at the urban primary care site, with a behavioral sleep problem and without medical (e.g., sickle cell disease; diabetes) or neurodevelopmental (e.g., autism spectrum disorder) conditions that would impact sleep. A sleep problem was defined by either (a) a caregiver-reported “small” to “severe” child sleep problem, based on an item used extensively in previous research (Mindell, Sadeh, Kwon, & Goh, 2013; Quach, Hiscock, Ukoumunne, & Wake, 2011) or (b) insufficient total (24-hr) sleep, based on national guidelines (<11 hr for age 2; <10 hr for ages 3–5 years; Hirshkowitz et al., 2015).

Clinicians were recruited via e-mail and staff presentations; participants were eligible for the study if they were English-speaking and providing pediatric patient care at one of the three urban primary care sites. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The children’s hospital Institutional Review Board approved this study. We followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting of Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, 2007).

Procedure

We used the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), a widely used implementation science framework, to develop semi-structured interviews that would inform subsequent intervention adaptation and implementation (Damschroder et al., 2009). CFIR considers factors in five domains: (a) the characteristics of the individuals involved in the intervention; (b) the intervention characteristics; (c) the intervention implementation process; (d) the inner setting (in this study, the primary care clinic and healthcare system); and (e) the outer setting (i.e., the broader socio-cultural context). We focused primarily on the domains of the characteristics of the individuals involved in the intervention, the evidence-based intervention components, and the implementation process. An interview guide for each stakeholder group was pilot tested and refined by four study team members (A. A. W., K. A. R., R. S. B., and J. A. M.). Interview guides included questions about interviewees’ perceptions of child sleep problems and management. Interviewees were then presented with a handout of common components of evidence-based behavioral sleep interventions for pediatric insomnia or insufficient sleep and asked about potential barriers to and facilitators of implementing each component. The components were selected on the basis of evidence-based pediatric behavioral sleep intervention research (Allen et al., 2016; Meltzer & Mindell, 2014; Mindell et al., 2006) and included: maintaining a bedtime before 9:00 p.m., a consistent sleep schedule and bedtime routine, and adequate sleep duration; avoiding caffeine; avoiding electronics items before bedtime; having the child fall asleep independently; and managing tantrums at bedtime. Interview questions also focused on intervention adaptability, preferred implementers, the implementation process, and the healthcare context. The interview guides and handout are provided in Supplementary Appendix S1.

Interviews were conducted by the lead author (A. A. W.) and two supervised clinical psychology doctoral students (B. W. and I. M.). One interviewer (A. A. W.) had previously worked with three of the clinicians. Interviews were audio-recorded in private locations at the main hospital or the primary care site; one interview was audio-recorded with a caregiver participant by telephone due to family transportation difficulties. Caregiver study visits ranged from 45 to 90 min and included questionnaire and interview administration. The study team extracted child demographic data (age, race/ethnicity, and sex) from the EHR. Caregivers were compensated $45 for participation. Clinician study visits ranged from 30 to 60 min and included questionnaire and interview administration. Clinicians were compensated with a $20 gift card. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and uploaded into NVivo version 12 for analysis.

Measures

Caregiver Questionnaires

Caregivers reported their sociodemographic information, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, income, and household size. Income and household size were used to identify family SES position based on U.S. poverty guidelines.

Caregivers reported on child sleep patterns and problems using the 30-item Brief Child Sleep Questionnaire (BCSQ), which has shown good reliability and moderate correspondence with actigraphy (Kushnir & Sadeh, 2013; Sadeh, Mindell, Luedtke, & Wiegand, 2009). Caregivers reported on child sleep location, bed and wake times, bedtime routine frequency, bedtime resistance severity, sleep onset latency, nighttime sleep duration, night awakening frequency and duration, naps, and severity of the child sleep problem over the last 2 weeks. Caregivers also reported on child caffeine consumption and the number of electronics items in the child’s sleep space (Williamson & Mindell, 2020). In line with other studies (Mindell et al., 2013; Sadeh et al., 2009), caregiver-estimated nighttime sleep and nap durations were summed to obtain total (24-hr) child sleep duration and a sleep opportunity variable was calculated as the number of hours between caregiver-reported child bedtime and waketime.

Caregivers also completed the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale—Short Form (CES-D-10), which has good psychometric properties (Cheung, Liu, & Yip, 2007). A cutoff score of 10 indicates clinically significant symptoms (Cheung et al., 2007).

Clinician Questionnaires

Clinicians reported on their demographic information, education, current position, number of years in practice, and any prior pediatric sleep training.

Analytic Approach

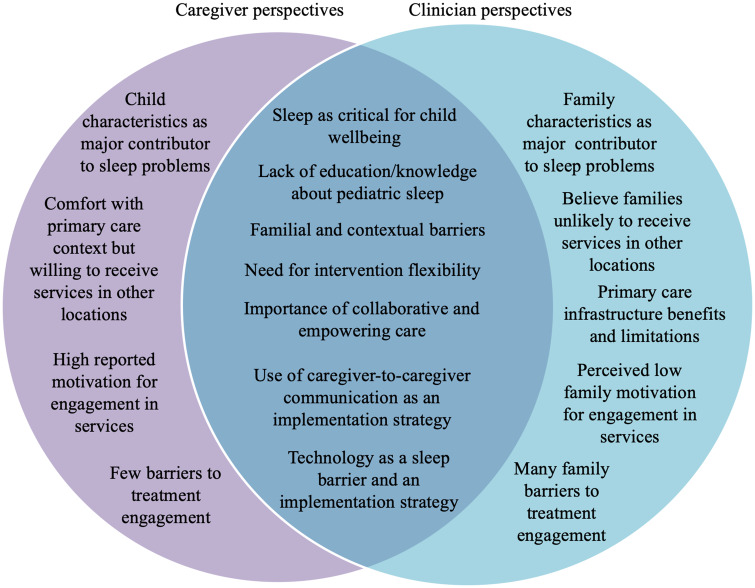

Summary statistics (means and proportions) were generated for quantitative data. Qualitative data analysis followed an integrated approach (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, 2007). Two types of codes were developed: a priori CFIR-related codes and grounded theory codes that emerged from the data. We created an operational definition for each code and decision rules for their application. Research team members (A. A. W., B.W., and I.M.) first separately coded three transcripts, compared their coding, and developed an initial codebook with oversight from a qualitative methods expert (K. A. R.). The codebook was then applied to three additional transcripts, compared across coders, and further refined. Coding disagreements were resolved through discussion. The finalized codebook was then applied to all transcripts; 20% of the transcripts were double-coded by the coders (A. A. W., B.M., and I.M.) for reliability purposes. The weighted kappa was 0.79. The organization of themes (Figure 1) across stakeholder groups was determined by thematic saturation and consensus among the research team, including two qualitative experts (K. A. R. and F. K. B.).

Figure 1.

Convergence and divergence in caregiver and primary care clinician perspectives.

Results

Participant Sociodemographic Information

Caregivers (N = 23; Table I) were mostly mothers (96%) who identified as Black (86%). The majority of caregivers were the single caregiver at home (70%) and living at or below 125% of the U.S. poverty level (65%). A total of 17% caregivers endorsed clinically significant (≥10) depressive symptoms. Clinicians (N = 22) were mostly female (87%) of non-Latinx White backgrounds (73%). Clinicians included primary care physicians (59%), nurse practitioners (9%), licensed social workers (23%), and psychologists providing integrated behavioral health services at the primary care sites (9%). See Table I for additional sociodemographic information.

Table I.

Participant Sociodemographic Information

| Variables | Caregivers (N = 23), mean (SD)/% | Children (N = 23), mean (SD)/% | Clinicians (N = 22), mean (SD)/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 96% | 48% | 87% |

| Race: Black or African American | 83% | 78% | 18% |

| White | 17% | 9% | 73% |

| Other or multiple races | – | 13% | – |

| Asian | – | – | 9% |

| Ethnicity: Hispanic/Latinx | 4% | 4% | – |

| Age | 2.7 years (0.92) | ||

| 18–24 years | 17% | – | |

| 25–29 years | 17% | 4.5% | |

| 30–39 years | 57% | 45.5% | |

| 40–49 years | 9% | 27.3% | |

| ≥50 years | – | – | 22.7% |

| Highest educational level obtained | |||

| ≤High school/secondary school | 48% | – | |

| Some college/junior college | 30% | – | |

| College/university | 13% | – | |

| Postgraduate | 9% | 100% | |

| Number of children living in home | 2.4 (0.99) | ||

| Number of adults living in the homea | 1.7 (0.82) | ||

| Single caregiver household | 70% | ||

| Married | 21% | ||

| Unmarried, cohabitating | 9% | ||

| US poverty level: ≤125% | 65% | ||

| ≤133% | 4% | ||

| ≤150% | 4% | ||

| ≤200% | 5% | ||

| 250% or more | 22% | ||

| Clinician prior education in pediatric sleepb and source | 32% | ||

| Bachelor’s program | 5% | ||

| Medical school or residency | 23% | ||

| Continuing education course | 9% | ||

| Hospital/employer training | 5% | ||

| Other experience (clinical) | 9% |

Note. “Adults” indicates individuals 18 years of age or older in the home.

Types of prior pediatric sleep education are not mutually exclusive.

Child Sleep Patterns and Problems

Table II shows caregiver-reported child sleep patterns and problems. Consistent with inclusion criteria, nearly all (95.7%) caregivers reported a child sleep problem and most (65.2%) reported insufficient total (24-hr) child sleep. The average bedtime was 8:48 p.m., which aligns with early childhood guidelines of a bedtime before 9:00 p.m. (Mindell, Meltzer, Carskadon, & Chervin, 2009), but average sleep onset latency and night awakening duration were markedly prolonged (>2 hr), resulting in extremely curtailed reported average nighttime sleep (6.41 hr). Poor sleep health behaviors and insomnia symptoms identified on the basis of previous research (Williamson & Mindell, 2020) were highly prevalent, as expected based on inclusion criteria. Almost all (91%) children lacked a consistent bedtime routine, 74% had one or more electronics items in the bedroom, and 38% consumed caffeine daily (26% iced tea, 17% soda). Most caregivers reported child bedtime resistance (87%), difficulty falling asleep (78%), a prolonged sleep onset latency (87%), and frequent night awakenings (52%).

Table II.

Descriptive Statistics For Caregiver-Reported Child Sleep Patterns and Problems (N = 23)

| Sleep patterns | Mean (SD)/% |

|---|---|

| Sleep location | |

| Own room, own bed | 30% |

| Shared room with caregiver(s), own bed | 17% |

| Shared room with caregiver(s), shared bed | 44% |

| Shared room with sibling(s), own bed | 4% |

| Couch shared with parent, sibling, or other person | 4% |

| Bedtime | 8:48 p.m. (51 min) |

| Number of awakenings per night | 0.52 (0.51) |

| Duration of nighttime awakenings (min) | 158.13 (190.87) |

| Wake time | 7:10 a.m. (113 min) |

| Nighttime sleep opportunity (hr) | 10.36 (1.98) |

| Nighttime sleep duration (hr) | 6.41 (2.53) |

| Takes naps | 83% |

| Nap duration (min) | 111.09 (85.47) |

| Total (24-hr) sleep duration (hr) | 8.27 (2.22) |

| Poor sleep health behaviors | Mean (SD)/% |

| Inconsistent bedtime routine (≤4 nights/week) | 91% |

| Bedtime later than 9:00 p.m. | 61% |

| One or more electronics item in bedroom | 74% |

| Type of electronics itema | |

| Television | 48% |

| Tablet | 52% |

| Smartphone/cellphone | 39% |

| Gaming device | 4% |

| Insufficient sleep | 65% |

| Consumes caffeine daily | 36% |

| Insomnia symptoms | Mean (SD)/% |

| Bedtime resistance | 87% |

| Difficulty falling asleep | 78% |

| Sleep onset latency ≥30 min | 87% |

| Night awakenings ≥3 times/week | 52% |

| Sleep problem | 96% |

Note. Categories are not mutually exclusive. Insomnia symptoms and poor sleep health behaviors identified on basis of previous research (Williamson & Mindell, 2020).

Qualitative Themes

Qualitative analysis revealed convergence and divergence in themes across stakeholder groups, as shown in Figure 1 and described further below.

Importance of Child Sleep

Caregivers and clinicians conceptualized sleep as being critical for child wellbeing, although the impact of poor sleep on multiple aspects of child functioning (emotion regulation and academic performance) was described in more detail by clinicians (Table III). Many clinicians also indicated that families they treat do not always realize the extent of linkages between sleep and child functioning. Clinicians often described making the connection between sleep and child wellbeing more explicit for families during their visits.

Table III.

Selected Themes and Representative Quotes

| Theme/sub-theme | Caregiver quote | Clinician quote |

|---|---|---|

| Sleep as critical for child wellbeing |

|

|

| Lack of education/knowledge about pediatric sleep |

|

|

| Child versus family characteristics as major contributor to sleep problems |

|

|

Familial and contextual barriers to intervention components

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Need for intervention content flexibility |

|

|

| Importance of empowering and collaborative care |

|

|

| Caregiver-to-caregiver communication as an implementation strategy |

|

|

| Technology as an implementation strategy |

|

|

| Willingness/lack of willingness to receive services outside of primary care |

|

|

| Barriers to treatment access and engagement |

|

|

Lack of Education/Knowledge About Pediatric Sleep

Both caregivers and clinicians identified a need for more patient and family education about healthy sleep habits and behavioral sleep intervention strategies in primary care. Some clinicians also expressed a need for more knowledge and resources in this regard for themselves (Table III). Many caregivers were surprised about recommendations related to optimal child sleep duration, including dietary advice related to limiting caffeine. Clinicians similarly described families as being unaware of these particular recommendations as well as the negative impact of nighttime electronics usage on sleep.

Child Versus Family Factors as Major Contributors to Sleep Problems

In discussing the importance of sleep as well as barriers to sleep intervention, caregivers primarily identified challenging child characteristics, such as being “difficult,” “full of energy,” “headstrong,” or an inherently poor sleeper as being the main contributor to the child’s sleep problem. By contrast, clinicians emphasized the family context as the main contributor to child sleep problems. In this regard, clinicians consistently described caregiver limit-setting difficulties and disorganized home environments as contributing to sleep problems and poor sleep habits (Table III).

Familial and Contextual Barriers

In response to questions about barriers impacting family-driven intervention components (Figure 1), both caregivers and clinicians similarly highlighted familial and contextual factors. These included: caregiver work schedules; having to manage multiple children; challenges in aligning different caregivers (e.g., co-parenting) and child sleep locations; caregiver stress and exhaustion; and family reliance on electronic items.

Caregivers and clinicians raised these barriers in relation to all of the intervention components, frequently referencing multiple barriers simultaneously. For instance, inflexible or variable work schedules and having multiple children at home resulted in later bedtimes and inconsistent routines. Caregivers and clinicians also noted that having multiple caregivers and, in some cases, multiple sleep locations, impeded management of child behaviors and enforcement of rules around electronics and caffeine. Reflecting the multilevel and interactive nature of these barriers, one caregiver described the impact of her partner’s nighttime work schedule on co-sleeping, which was also influenced by neighborhood safety concerns (Table III).

Caregivers and clinicians also discussed caregiver stress and exhaustion as barriers to implementing intervention components. As presented in Table III, a quote from one caregiver explained her level of frustration at the end of the day when, after being with her child or at work all day, his behavior is the most challenging to address. Likewise, clinicians described caregivers as being “overwhelmed” due to difficult work schedules and limited social support.

Families’ reliance on electronics at nighttime was another barrier that permeated most of the intervention components. For instance, caregivers and clinicians gave examples of children staying up late or waking overnight to use electronics, refusing to follow a bedtime routine or stay in bed without electronics, and caregivers providing children with electronics to offset caregiver stress or competing demands. Caregivers and clinicians also described family habits perpetuating nighttime electronics usage, such as children sleeping in shared spaces with adults using electronics, children modeling family behaviors (i.e., using devices in bed), or the belief that electronics items would help their child fall asleep, based on caregivers’ own experiences.

Caregivers and clinicians also noted other contextual factors including close living quarters as barriers. Some caregivers and clinicians described concerns that neighbors in close proximity could easily hear a child crying or having a tantrum at bedtime, leading to caregivers being unable to ignore or otherwise tolerate these behaviors. In addition to feeling embarrassed about neighbors hearing her child and commenting about this, one caregiver stated that a crying child at bedtime would likely cause a neighbor to report the family to child protective services.

Need for Intervention Content Flexibility

In response to questions about facilitators of intervention content, caregivers and clinicians converged in their view about a flexible intervention approach. One caregiver described feeling as though unmodified extinction (“cry it out”) was the only method to help her child sleep independently, and wanted more options and individualized information (Table III). Clinicians also discussed flexibility with regard to guideline recommendations, especially concerning a bedtime before 9:00 p.m., emphasizing instead bedtime routine consistency and sleep duration as more important and realistic goals.

Importance of Empowering and Collaborative Care

Another intervention facilitator that aligned across stakeholder groups was the importance of care that was both empowering and collaborative, with partnerships between caregivers and clinicians and between caregivers and other family members. A clinician described empowering families to make change by eliciting intervention ideas from families, while another clinician discussed that empowering a caregiver to make change often leads to supporting collaboration with all family stakeholders. Many clinicians emphasized “getting everyone on the same page” in the family to collaborate and support sleep recommendations. Caregivers also expressed a desire for a more collaborative approach through increased empathy, and problem-solving with clinicians and raised the need for family members to work together (“get on board”) for effective intervention implementation.

Caregiver-to-Caregiver Communication as an Implementation Strategy

Caregivers reported that they would feel comfortable with individual-level treatment and uniformly expressed comfort with having a behavioral health clinician deliver a sleep intervention. Many were also enthusiastic about group treatment, stating that this format could help them learn from other parents and feel less isolated and more supported in managing their child’s sleep problem. Clinicians discussed similar group treatment benefits but expressed feasibility concerns related to the ease of scheduling and the need for an experienced group facilitator to support this format.

Technology as an Implementation Strategy

Despite the consistent identification of electronic items as a barrier to evidence-based sleep recommendations, caregivers and clinicians both strongly endorsed the use of technology as an implementation strategy. In addition to the two in-person office visits and phone call check-ins presented to participants as part of a potential intervention delivery and implementation process, caregivers and clinicians agreed that text messages and e-mail communication were potentially helpful methods to deliver psychoeducation and reminders about intervention strategies. Many caregivers discussed having difficulty keeping track of paper-based handouts and asked whether they could receive this information electronically. Several clinicians also referenced the potential for videos to help reinforce positive bedtime behaviors and intervention strategies in between sessions (Table III).

Caregiver/Family Comfort With the Primary Care Context and Willingness to Travel to Obtain Sleep Services

Caregivers discussed feeling comfortable receiving sleep services at their child’s primary care site, but indicated they were very willing to pursue services elsewhere (i.e., specialty care or a community health center). Several caregivers mentioned that receiving a referral from their child’s pediatrician for a primary care-based sleep intervention would be an important facilitator due to feelings of trust in and comfort with the clinician. By contrast, clinicians perceived families to be less willing to seek services outside of primary care or follow-up on referrals, however, citing the familial and contextual barriers described above.

Primary Care Infrastructure Benefits and Limitations

Clinicians discussed benefits and limitations of the primary care context. One infrastructure benefit was the use of the EHR to provide sleep intervention referrals and facilitate coordinated care across primary care and behavioral health clinicians. Two of the three urban primary care sites also have integrated primary care (IPC) psychologists providing behavioral health services; the third primary care site has plans to initiate these services. Clinicians at the sites with existing IPC services referenced the ease of implementing the sleep intervention into this existing model of brief behavioral health treatment in primary care. Clinicians without current IPC services suggested having a sleep interventionist available for “warm hand-off” referrals to the program.

The need to address multiple concerns in a short office visit was noted as an infrastructure limitation especially by physicians and nurse practitioners across sites. Clinicians described having to “pick their battles” with families, resulting in limited time and attention to sleep habits. The need for additional clinician training and resources was also identified as an infrastructure limitation. Some clinicians also raised questions about intervention sustainability if the program were implemented only as part of a research study and not as part of existing IPC services in future implementation efforts. Finally, many clinicians raised the issue of limited clinic space, even in clinics with IPC services and dedicated behavioral health office space.

Treatment Motivation and Engagement

Whereas caregivers expressed a high level of motivation to engage in a sleep intervention, with many asking if they could be contacted when a program begins, clinicians raised concerns about family motivation and treatment engagement, with many referencing low show rates for primary care and IPC behavioral health visits. Many clinicians emphasized familial and contextual barriers similar to those described above, such as caregivers’ work schedules, household disorganization, childcare needs, and transportation barriers. Caregivers only noted the need for evening hours and flexible scheduling. Some clinicians suggested providing transportation passes, meals, and childcare during visits to mitigate these challenges if the sleep intervention were implemented in a future research study.

Discussion

This study identified caregiver and primary care clinician perceptions about implementing evidence-based early childhood behavioral sleep intervention in urban primary care with families of primarily lower SES backgrounds. Patterns of convergence and divergence in perspectives that emerged can guide future intervention adaptation and implementation efforts.

Consistent with previous qualitative research on sleep among families of lower SES with young children, caregivers felt sleep was highly important for child wellbeing (Caldwell et al., 2020; Lindsay et al., 2018) and endorsed the need for more sleep education and resources. Caregivers were often unaware of which beverages contained caffeine and were surprised by 24-hr child sleep duration guidelines (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015). Clinicians echoed these views and perceived sleep to be important but under-valued by families. They also wanted more resources to educate themselves about behavioral sleep strategies, in line with both qualitative and quantitative studies of clinician perceptions about pediatric sleep (Boerner, Coulombe, & Corkum, 2015; Honaker & Meltzer, 2016). These findings highlight the potential positive impact of more accessible caregiver- and clinician-directed sleep education to support increased primary care-based sleep problem assessment and treatment. Some caregiver-directed education has resulted in modest sleep improvements in children of lower SES (Mindell et al., 2016). Of note, one study found that caregiver sleep knowledge initially increased post-intervention, but declined over time, despite sustained child sleep duration improvements (Wilson et al., 2014).

Given the complexity and interaction of familial and contextual barriers identified in this study, caregiver education alone is unlikely to sufficiently address behavioral child sleep problems. As in other studies (Caldwell et al., 2020), many of these barriers such as work schedules or single caregiver homes are not readily modifiable. However, findings suggest that these barriers could be addressed by adapting intervention components and delivery methods to better align with the participant-identified approaches. Implementing intervention content flexibly, with tailoring to the child and family environment and fidelity to the intervention evidence base is not a new concept (Kendall, Gosch, Furr, & Sood, 2008), and is something that clinicians may already do. Yet with the dearth of evidence on the efficacy of behavioral sleep interventions with families of lower SES (Schwichtenberg et al., 2019), there is a need for future work to provide an evidence base for adapting and using these interventions flexibly. For instance, focusing on the regularity and duration of early childhood sleep as opposed to the timing (i.e., a bedtime before 9:00 p.m.) in shift-working families and reducing bedtime electronics rather than eliminating them altogether due to shared sleep spaces are flexible approaches that could be tested in an intervention trial. Explicitly adapting an intervention to prioritize caregiver empowerment, address high levels of caregiver stress, and encourage collaboration both between the clinician and the caregiver and between the caregiver and other family members are additional strategies that should be tested in behavioral sleep intervention research. These efforts may also help to improve treatment engagement in stressed families, similar to previous research in the field of behavioral parent training (Kazdin & Whitley, 2003).

Future research should explore the benefits of group behavioral sleep problem treatment, which was strongly supported by both caregivers and clinicians, although this format could limit the extent of individual intervention tailoring. Stakeholders preferred technology-enhanced intervention delivery, with content sent to families via e-mail or text messages. This strategy could also enhance treatment engagement, as greater interventionist-family phone contact was linked to increased treatment engagement in a parent training in urban primary care (Walton et al., 2014). At the same time, using technology to enhance intervention delivery could contribute to families’ reported reliance on electronics for themselves and as a method to manage difficult child behaviors, or could divide caregivers’ already limited attention at bedtime. Our results and the literature suggest that any technology-based intervention should be balanced with efforts to reduce evening electronics. For example, reminders about the bedtime routine or reducing device usage could be sent in the early evening to caregivers as opposed to immediately before bedtime.

Divergence in stakeholder perspectives also has implications for clinical practice, treatment adaptations, and future research. Caregivers’ focus on challenging child characteristics rather than on the family environment as the main contributor to a child sleep problem, along with the desire for collaborative care, indicates that clinicians should elicit caregiver beliefs about child sleep, empathize with caregivers, and tailor intervention accordingly. Making modifications where possible to family behaviors and values (e.g., improving limit-setting; reducing electronics usage) is still necessary, but could be presented to families more clearly as a method to manage challenging child behaviors rather than improve family behaviors.

Caregivers and clinicians also diverged in their perspectives on families’ willingness to seek services outside of primary care, treatment motivation, and engagement. Clinicians identified barriers to family engagement similar to those found in a study of caregiver-perceived barriers to engagement in early childhood behavioral health services (Ofonedu et al., 2017). This discrepancy could be due to clinicians reflecting on their experiences with their patients, whereas caregivers had not yet participated in a primary-care based sleep intervention, potentially making it difficult to identify barriers. Caregivers we interviewed were also those who were motivated to participate in research and attend an interview, and could be more engaged or motivated families. Nonetheless, given the sociodemographic differences (race/ethnicity and education) between the caregiver and clinician groups and literature on the impact of implicit racial bias in particular on clinician practices and health disparities (Maina, Belton, Ginzberg, Singh, & Johnson, 2018) examining clinician biases and sleep treatment practices is a critical direction for future research.

Study findings indicate that primary care is a viable context for sleep intervention, especially in practices with existing IPC services. However, additional clinician training and resources are needed, even among behavioral health providers. Planning for the use of practice space, integrating intervention referral information into the EHR, and ensuring that intervention practices are sustainable are considerations that all can inform planning and future research. In making adaptations to primary care service delivery and sleep intervention components, it will be critical to continue to identify stakeholder perceptions of acceptability, feasibility, and barriers.

It is important to note that study findings do not reflect the experiences of all individuals in specific racial, ethnic, or SES groups. This study was not designed to examine variation in themes by different sociodemographic groups. Comparing themes by sociodemographic group as well as by clinician level of training in pediatric sleep are important future research directions. Barriers related to caregiver work schedules and multiple children may also be regularly experienced by families across the SES continuum. Future research should explore caregiver and clinician perceptions about sleep and sleep intervention in families of other sociodemographic backgrounds. Results are additionally limited by potential response bias, as those who chose to participate in this study may view sleep as being more important or have increased knowledge about sleep. Interview questions about the importance of sleep may also have influenced interview responses. Study findings are specific to young children with behavioral sleep problems who do not have medical or neurodevelopmental comorbidities. Given the high prevalence of sleep problems in children with medical and neurodevelopmental comorbidities, research should further explore perspectives among patients with complex needs, their caregivers, and their treating clinicians. This study was conducted at clinics affiliated with a large academic medical system. Two of these clinics had integrated behavioral health services. Research on barriers and facilitators of sleep intervention in other primary care settings, including those without integrated behavioral health providers, is needed.

Conclusions

For families of predominantly lower SES with young children and urban primary care clinicians, our results highlight the ways in which evidence-based behavioral sleep interventions may need adaptations to be optimally effective in urban primary care. Tailoring evidence-based intervention to address modifiable familial and contextual factors and using flexible, empowering, and collaborative approaches are promising strategies to support intervention delivery and effectiveness. Attending to these factors and enhancing intervention delivery to align with stakeholder preferences could also help to address clinician-perceived family treatment access and engagement barriers, potentially reducing SES-related disparities in child sleep and related developmental outcomes.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data can be found at: https://academic.oup.com/jpepsy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the network of primary care clinicians, their patients, and families for their contribution to this project and clinical research facilities through the Pediatric Research Consortium at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Funding

Dr. A. A.Williamson was supported by the Sleep Research Society Foundation and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD094905). Dr. K. A. Rendle has a research grant through the Lung Cancer Research Foundation that is partly supported by Pfizer. Dr. A. G. Fiks is the co-inventor of decision support software known as the Care Assistant; he has earned no income and does not hold a patent from this invention. In the past, Dr. A. G. Fiks received an independent research grant from Pfizer that supported his research team, but did not support his salary.

References

- Allen S. L., Howlett M. D., Coulombe J. A., Corkum P. V. (2016). ABCs of SLEEPING: A review of the evidence behind pediatric sleep practice recommendations. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 29, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathory E., Tomopoulos S., Rothman R., Sanders L., Perrin E. M., Mendelsohn A., Yin H. S. (2016). Infant sleep and parent health literacy. Academic Pediatrics, 16, 550–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe D. W. (2011). Cognitive, behavioral, and functional consequences of inadequate sleep in children and adolescents. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 58, 649–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerner K. E., Coulombe J. A., Corkum P. (2015). Barriers and facilitators of evidence-based practice in pediatric behavioral sleep care: Qualitative analysis of the perspectives of health professionals. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 13, 36–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley E. H., Curry L. A., Devers K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell B., Ordway M., Sadler L., Redeker N. (2020). Parent perspectives on sleep and sleep habits among young children living with economic adversity. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 34, 10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung Y. B., Liu K. Y., Yip P. S. (2007). Performance of the CES‐D and its short forms in screening suicidality and hopelessness in the community. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 37, 79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder L. J., Aron D. C., Keith R. E., Kirsh S. R., Alexander J. A., Lowery J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M., Bagley E. J., Keiley M., Elmore-Staton L., Chen E., Buckhalt J. A. (2013). Economic adversity and children’s sleep problems: Multiple indicators and moderation of effects. Health Psychology, 32, 849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes M., Camerota M., Propper C. B. (2019). Neighborhood deprivation predicts infant sleep quality. Sleep Health, 5, 148–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz M., Whiton K., Albert S. M., Alessi C., Bruni O., DonCarlos L., Adams Hillard P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: Methodology and results summary. Sleep Health: Journal of the National Sleep Foundation, 1, 40–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker S. M., Meltzer L. J. (2016). Sleep in pediatric primary care: A review of the literature. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 25, 31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker S. M., Saunders T. (2018). The sleep checkup: Sleep screening, guidance, and management in pediatric primary care. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 6, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin A. E., Whitley M. K. (2003). Treatment of parental stress to enhance therapeutic change among children referred for aggressive and antisocial behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 504–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall P.C., Gosch E., Furr J.M., Sood E. (2008). Flexibility within fidelity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 987–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir J., Sadeh A. (2013). Correspondence between reported and actigraphic sleep measures in preschool children: The role of a clinical context. J Clin Sleep Med, 09, 1147–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay A., Moura Arruda C., Tavares Machado M., De Andrade G., Greaney M. (2018). Exploring Brazilian immigrant mothers’ beliefs, attitudes, and practices related to their preschool-age children’s sleep and bedtime routines: A qualitative study conducted in the United States. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maina I. W., Belton T. D., Ginzberg S., Singh A., Johnson T. J. (2018). A decade of studying implicit racial/ethnic bias in healthcare providers using the implicit association test. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer L. J., Mindell J. A. (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 932–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileva-Seitz V. R., Bakermans-Kranenburg M. J., Battaini C., Luijk M. P. (2017). Parent-child bed-sharing: The good, the bad, and the burden of evidence. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 32, 4–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller B. F., Petterson S., Burke B. T., Phillips R. L. Jr., Green L. A. (2014). Proximity of providers: Colocating behavioral health and primary care and the prospects for an integrated workforce. American Psychologist, 69, 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J. A., Kuhn B., Lewin D. S., Meltzer L. J., Sadeh A. (2006). Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep, 29, 1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J. A., Meltzer L. J., Carskadon M. A., Chervin R. D. (2009). Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: Findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Medicine, 10, 771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J. A., Sadeh A., Kwon R., Goh D. Y. (2013). Cross-cultural differences in the sleep of preschool children. Sleep Medicine, 14, 1283–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J. A., Sedmak R., Boyle J. T., Butler R., Williamson A. A. (2016). Sleep well!: A pilot study of an education campaign to improve sleep of socioeconomically disadvantaged children. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 12, 1593–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ofonedu M. E., Belcher H. M., Budhathoki C., Gross D. A. (2017). Understanding barriers to initial treatment engagement among underserved families seeking mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 863–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy S., Carskadon M. A., Jean-Louis G., Owens J., Bramoweth A., Combs D., Buysse D. (2016). Implementation of Sleep and Circadian Science: Recommendations from the Sleep Research Society and National Institutes of Health Workshop. Sleep, 39, 2061–2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña M.-M., Rifas-Shiman S. L., Gillman M. W., Redline S., Taveras E. M. (2016). Racial/ethnic and socio-contextual correlates of chronic sleep curtailment in childhood. Sleep, 39, 1653–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quach J., Hiscock H., Ukoumunne O. C., Wake M. (2011). A brief sleep intervention improves outcomes in the school entry year: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics, 128, 692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud E., Vecchierini M. F., Heude B., Charles M. A., Plancoulaine S. (2018). Sleep and its relation to cognition and behaviour in preschool‐aged children of the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Sleep Research, 27, e12636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A., Mindell J. A., Luedtke K., Wiegand B. (2009). Sleep and sleep ecology in the first 3 years: A web-based study. Journal of Sleep Research, 18, 60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwichtenberg A., Abel E., Keys E., Honaker S. M. (2019). Diversity in pediatric behavioral sleep intervention studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 47, 103–111. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. P., Hardy S. T., Hale L. E., Gazmararian J. A. (2019). Racial disparities and sleep among preschool aged children: A systematic review. Sleep Health, 5, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sviggum G., Sollesnes R., Langeland E. (2018). Parents’ experiences with sleep problems in children aged 1–3 years: A qualitative study from a health promotion perspective. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 13, 1527605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troxel W. M., Germain A., Buysse D. J. (2012). Clinical management of insomnia with brief behavioral treatment (BBTI). Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 10, 266–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton J. R., Mautone J. A., Nissley-Tsiopinis J., Blum N. J., Power T. J. (2014). Correlates of treatment engagement in an ADHD primary care-based intervention for urban families. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 41, 539–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A., Mindell J. (2020). Cumulative socio-demographic risk factors and sleep outcomes in early childhood. Sleep, 43, zsz233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. E., Miller A. L., Bonuck K., Lumeng J. C., Chervin R. D. (2014). Evaluation of a sleep education program for low-income preschool children and their families. Sleep, 37, 1117–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.