Abstract

Background

Young children from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds are at risk for poor sleep, yet few studies have tested behavioral interventions in diverse samples. This study tests factors that could contribute to associations between parenting skills and child sleep to inform interventions for children at risk of poor sleep outcomes. Specifically, we examined household chaos, caregiver sleep knowledge, and caregiver sleep quality as putative mediators that may be relevant to interventions seeking to improve child sleep.

Methods

Caregivers (M age 31.83 years; 46.2% African American; 52.1% Hispanic/Latinx, 95% female) of 119 1- to 5-year-old children (M age 3.99 years; 43.7% African American; 42.0% Hispanic/Latinx, 14.3% biracial; 51.3% female) completed measures of parenting practices, child and caregiver sleep, household chaos, and sleep knowledge. Indices of pediatric insomnia symptoms (difficulty falling/remaining asleep) and sleep health (sleep duration/hygiene) were constructed based on previous research. Parallel mediation models were conducted using ordinary least squares path analysis.

Results

Lower household chaos significantly attenuated the relationship between positive parenting skills and better child sleep health, suggesting chaos may serve as a potential mediator. There were no significant contributing factors in the pediatric insomnia model. Sleep knowledge was related to sleep health and caregiver sleep quality was related to pediatric insomnia, independent of parenting skills.

Conclusion

Interventions to improve sleep in early childhood may be enhanced by targeting parenting skills and household routines to reduce chaos. Future longitudinal research is needed to test household chaos and other potential mediators of child sleep outcomes over time.

Keywords: disparities, early childhood, household chaos, insomnia, mediators, parenting, sleep

Introduction

Behavioral sleep problems can negatively impact global child functioning. Insomnia, defined as difficulty falling and staying asleep, and poor sleep health, marked by insufficient duration for age and poor sleep hygiene (i.e., an inconsistent bedtime routine; electronics use bedtime; Williamson & Mindell, 2019), occur in 20–30% of young children (Mindell et al., 2006). Longitudinally, children who obtain insufficient or poor quality sleep in early childhood are at increased risk for obesity (Miller et al., 2019), socio-emotional problems (Sivertsen et al., 2015), and poor academic performance (Taveras, Rifas-Shiman, Bub, Gillman, & Oken, 2017).

Two recent systematic reviews (Guglielmo, Gazmararian, Chung, Rogers, & Hale, 2018; Smith, Hardy, Hale, & Gazmararian, 2019) suggest that preschool and school-aged children of African American or Hispanic/Latinx backgrounds (hereafter referred to as racial/ethnic minority) are at increased risk for insufficient sleep duration or poor sleep quality relative to non-Hispanic/Latinx White children (hereafter referred to as White). Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is also more common in children from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds (Marcus et al., 2013). Preschool children of racial/ethnic minority backgrounds are less likely to utilize regular bedtimes and routines than White children, which over time may lead to greater sleep time variability and insufficient sleep (Hale, Berger, LeBourgeois, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). It is also important to note that although racial and ethnic disparities persist even when controlling for socioeconomic status (SES; El-Sheikh et al., 2013; Hale et al., 2009), socioeconomic disadvantage has also been independently associated with poor sleep in children (Jarrin, McGrath, & Quon, 2014; Williamson & Mindell, 2019). As such, SES may be an additional risk factor for increased health disparities related to sleep in racial/ethnic minority children.

Cross-sectional research shows that sleep-related parenting behaviors may mediate the link between racial/ethnic minority status and bedtime behaviors in preschool children, suggesting the importance of cultural considerations when developing behavioral interventions (Patrick, Millet, & Mindell, 2016). Existing effective behavioral sleep interventions for young children typically focus on parenting skills (Meltzer & Mindell, 2014; Mindell & Williamson, 2018); however, the majority (>75%) of participants in behavioral sleep intervention studies are White (Schwichtenberg, Abel, Keys, & Honaker, 2019). Research has yet to examine whether racial/ethnic background is linked to variation in early childhood sleep intervention outcomes, but a recent study found that race/ethnicity moderated outcomes of a text message-based adolescent sleep intervention, with White youth demonstrating improvements in sleep that were not seen in racial/ethnic minority youth (Tavernier & Adam, 2017). Collectively, this research suggests that while there is a need to examine behavioral sleep interventions in racial/ethnic minority children, more research is needed on parenting skills and behavioral sleep intervention targets to inform intervention adaptation and development.

Household chaos, low caregiver knowledge, and poor caregiver sleep have all been linked to child sleep difficulties and may be potential mechanisms linking parenting skills and sleep health outcomes. Household chaos, defined as a loud crowded home lacking consistency (Matheny, Wachs, Ludwig, & Phillips, 1995), is predictive of global child health and may be an important determinant of health disparities in families with greater sociodemographic risk for poor health outcomes, including families of lower SES (Dush, Schmeer, & Taylor, 2013). Household chaos, although related to parenting, is a distinct construct reflecting the family environment that can predict child behavior beyond the contribution of parenting, and in some cases it moderates the relationship between parenting and child behavioral outcomes (Coldwell, Pike, & Dunn, 2006). In racial/ethnic minority preschool children enrolled in Head Start, household chaos mediated the relationship between child behavior and sleep, such that higher behavior problems were related to more household chaos and greater bedtime resistance (Boles et al., 2017). Interventions targeting household chaos may improve the regularity of daytime schedules and bedtime routines, the latter of which is a robust contributor to positive child sleep outcomes (Mindell & Williamson, 2018).

Caregiver sleep knowledge is commonly targeted in behavioral sleep interventions. In a recent meta-analysis of descriptive research, greater caregiver sleep knowledge was related to improved sleep hygiene, but not sleep duration (McDowall, Galland, Campbell, & Elder, 2017). Caregiver education level was also related to caregiver sleep knowledge, suggesting that families of lower SES may be at-risk for more limited sleep knowledge (McDowall et al., 2017). Although the relationship between parenting skills and sleep knowledge has not been tested, behavioral sleep interventions commonly address both parenting skills and caregiver sleep knowledge to improve child sleep outcomes (Meltzer & Mindell, 2014; Mindell & Williamson, 2018). Some sleep education interventions have demonstrated improvements in caregiver sleep knowledge (Jones, Owens, & Pham, 2013; Wilson, Miller, Bonuck, Lumeng, & Chervin, 2014). Interestingly, sleep education provided to families and their young children attending Head Start showed immediate increases in caregiver sleep knowledge that returned to baseline at the 1-month follow-up, while child sleep duration increased by 30 min from preintervention to follow-up (Wilson et al., 2014). This finding suggests that caregiver sleep knowledge and child sleep outcomes may be independent (Wilson et al., 2014). These conflicting results indicate that further study of caregiver sleep knowledge and child sleep outcomes is necessary.

Because caregiver and child sleep are closely related in early childhood (Meltzer & Mindell, 2007) and racial/ethnic minority status and lower SES are risk factors for poor sleep in adults (Grandner, Williams, Knutson, Roberts, & Jean-Louis, 2016), caregiver sleep may also function as a mechanism linking parenting practices and child sleep outcomes in racial/ethnic minority samples of lower SES. Poor caregiver sleep quality is associated with maternal mood, stress, and fatigue (Meltzer & Mindell, 2007). Parenting also suffers with poor caregiver sleep—mothers of toddlers who experience poor actigraphy-derived sleep quality and quantity report increased stress and fewer positive parenting behaviors (McQuillan, Bates, Staples, & Deater-Deckard, 2019). The relationship between caregiver and child sleep is especially relevant to families of racial/ethnic minority status who are more likely to cosleep than White families (Lozoff, Askew, & Wolf, 1996). Collectively, this work suggests that addressing sleep disturbances in caregivers may have a positive impact on child sleep. Although caregiver sleep has not been tested as a mediator between parenting and child sleep, it is possible that improving caregiver sleep may benefit child sleep by enhancing caregivers’ ability to enact positive parenting practices more effectively and to better manage child behaviors.

This study sought to examine parenting skills and child sleep outcomes and to test three putative mechanisms linking these constructs in a sample of racial/ethnic minority, lower SES families: (a) household chaos, (b) caregiver sleep knowledge, and (c) caregiver sleep. We hypothesized that positive parenting skills (supportive positive behavior, setting limits, and proactive parenting) would be related to reduced child insomnia symptoms and better sleep health through lower household chaos, higher caregiver sleep knowledge, and better caregiver sleep quality.

Materials and Methods

Participants

English and Spanish-speaking caregivers with children between the ages of 1 and 5 attending a university affiliated early childhood education center were eligible to participate in this study. The center’s mission is to improving outcomes for the most vulnerable children in Camden, New Jersey. Of 214 eligible children, 141 completed surveys (7 caregivers refused participation, the remaining 66 families were a passive refusal), and 119 child–caregiver dyads were used for the current analyses (reasons for removal from the final dataset: 4 siblings of another participant, 8 non-Hispanic/Latinx White children, and 11 dyads with incomplete data).

Procedures

This study was approved by the Rutgers University Institutional Review Board. Families were sent emails about the study including a link to participate prior to in person recruitment efforts. Research assistants approached caregivers during school drop-off, pick-up, and events to invite participation and complete informed consent. A native Spanish-speaking research assistant was utilized for Spanish-speaking caregivers. Measures were available in both English and Spanish and families were given the option to complete the measures at one time point either by paper packets or online via Qualtrics. Caregivers were given $10 gift cards for their participation.

Measures

Demographic Information

Caregivers reported their child’s age, sex, and race/ethnicity as well as their own age, race/ethnicity, education, employment, and marital status. Family income was used as a proxy for SES and obtained through school records.

Brief Infant/Child Sleep Questionnaire1

The Brief Infant/Child Sleep Questionnaire is a 30-item questionnaire that assesses child sleep quantity, routines, and the sleep environment and has demonstrated good reliability and moderate correspondence with actigraphy (Kushnir & Sadeh, 2013; Sadeh, 2004). Index scores were created for pediatric insomnia symptoms and sleep health based on previous research (Williamson & Mindell, 2019) with higher scores reflecting poorer sleep health habits and increased insomnia symptoms. The pediatric insomnia symptoms score included the following items coded as 1 to indicate insomnia symptoms and aggregated to compute a summary score: (a) degree of bedtime resistance difficulty (somewhat difficult, difficult, or very difficult), (b) difficulty falling asleep 3 or more nights a week, (c) a sleep onset latency of ≥30 min, (d) night awakenings ≥3 nights a week, and (r) caregiver-perceived sleep problem. The sleep health score included the following items, dichotomized with the unhealthy sleep habits coded as 1 and aggregated to compute a summary score: (a) bedtime later than 9:00 p.m., (b) bedtime routine occurring ≤4 times a week, (c) duration of sleep being less than the recommended 11 hr total 24-hr sleep for 2 years old or 10 hr total 24-hr sleep for 3–5 years old, and (d) child consumption of one or more caffeinated beverages per day.

Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire

The SDB subscale (Chervin, Hedger, Dillon, & Pituch, 2000) was used to assess SDB symptoms due to the increased risk of SDB in racial/ethnic minority children and the relationship between SDB and sleep quality (Marcus et al., 2013). The 15-item SDB subscale was found to validly predict symptoms of pediatric sleep-related breathing disorders, such as snoring and pauses in breathing during sleep, in children ages 2 to 18 years old. Items are rated as Yes, No, or I don’t know. A composite score was calculated dividing the total number of positive responses by the total number of responses, with higher scores indicating more SDB symptoms. Reliability in the current sample was moderate (α = .68).

Parenting Young Children

Parenting Young Children (PARYC; McEachern et al., 2012) was used to assess parenting skills. The PARYC includes three scales: supportive positive behavior, setting limits, and proactive parenting. Caregivers rated items on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from not at all to most of the time. A total score was computed combining all items, with higher scores indicating more positive parenting skills. Measure reliability was excellent (α = .88).

Parental Knowledge and Attitudes about Child Sleep1

Caregiver sleep knowledge and beliefs (Bonuck, Schwartz, & Schechter, 2016) were assessed through 10 true–false items about sleep in young children. The total percentage of correctly answered items was computed to indicate parental sleep knowledge, with higher scores indicating increased knowledge.

Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale

Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale (Haack, Gerdes, Schneider, & Hurtado, 2011; Matheny et al., 1995) is 15-item questionnaire that assesses disorganization and confusion at home (i.e., “It’s a real zoo in our house”). Items are rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Higher scores indicate greater household chaos. Reliability was good (α = .83) in the current sample.

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; Buysse, Reynolds, Monk, Berman, & Kupfer, 1989; Macıas & Royuela, 1996) is a well-validated measure of adult sleep. The 19-item questionnaire measures sleep quality and disturbance in the caregiver over the past month, with sleep disturbances rated on a 4-point Likert scale from never to three or more times per week. The PSQI yields a total score ranging from 0 to 21, with a higher score indicating worse sleep quality. Reliability was acceptable (α = .71) in the current sample.

Data Analysis

Pearson correlations were examined to assess associations among study variables. Parallel mediation models were conducted using ordinary least squares path analysis in the SPSS (version 26) PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013) to examine potential mediators linking parenting skills and child sleep outcomes with bootstrap confidence intervals to protect against violations in normality of the distribution. Potential mediators (household chaos, caregiver knowledge, and caregiver sleep) were entered together in one model predicting pediatric insomnia symptoms and in a second model predicting sleep health. Both models included child age, family income, and SDB symptoms as covariates due to their association with child sleep (Jarrin et al., 2014; Marcus et al., 2013; Mindell, Sadeh, Wiegand, How, & Goh, 2010).

Results

The final sample consisted of 119 child–caregiver dyads. Children were either African American (43.7%), Hispanic/Latinx (42.0%), or identified as biracial (14.3%); an average of 3.99 years old (SD = 1.06 years); and 51% of the sample was female (Table I). Most caregivers were biological parents (96.6%), female (95.0%), and were either African American (46.2%) or Hispanic/Latinx (52.1%). Most caregivers completed measures in English (88.2%). Descriptive values for study measures are presented in Table II. 55.5% of caregivers reported ≥ 1 symptom of pediatric insomnia. The most common symptom of pediatric insomnia was caregiver report of bedtime resistance, endorsed by 34.5% of caregivers. Twenty percent of the sample reported difficulty falling asleep, 28.6% reported sleep onset latency of ≥30 min, 18.5% reported night awakenings ≥ 3 nights per week, and 22.7% reported sleep problems. 94.1% of caregivers reported ≥1 poor sleep health behavior used to compute the sleep health index. The most commonly reported poor sleep health behavior was having one or more electronic device(s) in the bedroom (78.2%). A total of 40.3% had a bedtime routine ≤4 nights per week, 22.7% received inadequate sleep for age, 42.0% went to bed after 9 p.m., and 22.7% consumed caffeine.

Table I.

Sample Demographics

| Variable | N (%) of 119 |

|---|---|

| Child race/ethnicity | |

| Biracial–African American and Hispanic/Latinx | 17 (14.3) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 50 (43.7) |

| African American | 52 (42.0) |

| Child sex | |

| Female | 61 (51.3) |

| Male | 58 (48.7) |

| Caregiver race/ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 62 (52.1) |

| African American | 55 (46.2) |

| White | 1 (0.8) |

| More than 1 race selected | 1 (0.8) |

| Caregiver sex | |

| Female | 113 (95.0) |

| Male | 6 (5.0) |

| Caregiver marital status | |

| Single | 70 (58.8) |

| Married/engaged/living together | 44 (36.9) |

| Separated/divorced | 5 (4.2) |

| Relationship to child | |

| Biological parent | 115 (96.6) |

| Stepparent | 1 (0.8) |

| Grandparent | 3 (2.5) |

| Caregiver highest degree obtained | |

| None | 4 (3.4) |

| High school degree/GED | 63 (52.9) |

| Associate degree | 12 (10.1) |

| Vocational-tech degree | 7 (5.9) |

| College degree | 21 (17.6) |

| Graduate degree | 11 (9.2) |

| Annual household income | |

| $0–10,000 | 20 (16.8) |

| $10,001–20,000 | 15 (12.6) |

| $20,001–30,000 | 22 (18.5) |

| $30,001–40,000 | 36 (30.3) |

| $40,001–50,000 | 13 (10.9) |

| $50,000+ | 13 (10.9) |

GED = General Education Diploma

Table II.

Descriptives of Primary Variables and Correlations Among Variables

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child age | 3.99 (1.06) | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 2. Caregiver Age | 31.83 (7.08) | .07 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 3. Family income± | 2.38 (1.54) [$20–30,00 range] | −.04 | .16 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 4. SDBS | .13 (.15) | .13 | −.03 | .02 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 5. Pediatric insomnia symptoms | 1.24 (1.42) | −.16 | −.02 | .03 | .18* | 1.00 | |||||

| 6. Sleep health | 2.06 (1.19) | .01 | −.04 | −.01 | .08 | .07 | 1.00 | ||||

| 7. PARYC total score | 125.42 (16.62) | .07 | −.16 | −.02 | .10 | −.14 | −.01 | 1.00 | |||

| 8. Global PSQI | 6.29 (3.90) | .03 | .05 | .02 | .24** | .26** | .12 | .02 | 1.00 | ||

| 9. CHAOS total score | 2.09 (.63) | −.17 | .01 | .01 | .13 | .11 | .22* | −.24** | .24** | 1.00 | |

| 10. Caregiver sleep knowledge total score | 40.76 (19.62) | −.01 | .03 | .22* | .07 | .04 | −.16 | .05 | .12 | .01 | 1.00 |

SDBS = Sleep Disordered Breathing Scale. PARYC = Parenting Young Children; PSQI = Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; CHAOS = Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale.

p < .05;

p < .001; ± Spearman’s correlations to account for ordinal variable.

Preliminary Analyses

Associations among study variables were in the small to moderate range. Pediatric insomnia symptoms were related to greater SDB (r = .18, p = .046). Worse caregiver sleep was related to increased pediatric insomnia symptoms (r = .26, p = .005) and SDB (r = .24, p = .010). Increased household chaos was linked to worse sleep health (r = .22, p = .018), fewer positive parenting skills (r = −.24, p = .007), and worse caregiver sleep (r = .24, p = .008). Family income was positively associated with parent knowledge of sleep (rs = .22, p = .017).

Mediation Models

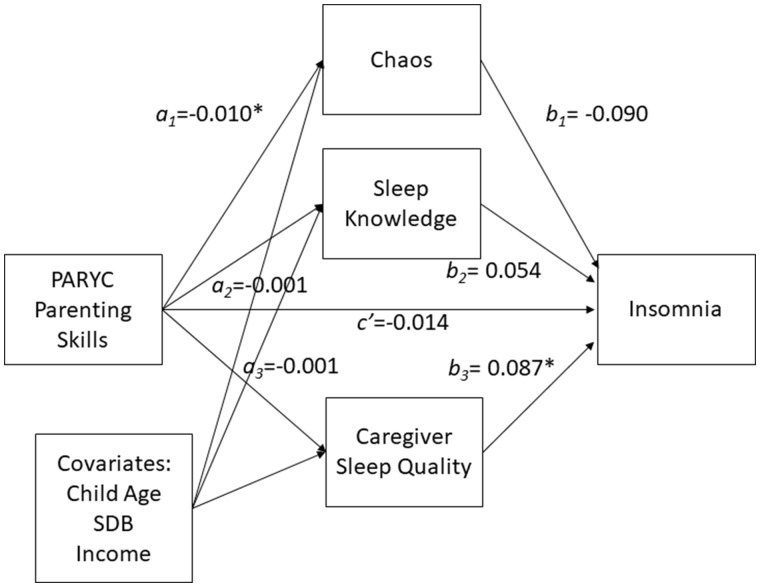

Using a bootstrapping model with covariates (Figure 1), there was no evidence of indirect effects of parenting skills on pediatric insomnia symptoms through household chaos, sleep knowledge, or caregiver sleep. There was no evidence of a direct effect of parenting on pediatric insomnia symptoms independent of its association with household chaos, caregiver sleep knowledge, or caregiver sleep (c’ = −.014, p = .084; Table III;Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Parallel mediation model testing chaos, sleep knowledge, and caregiver sleep quality as mediators between parenting and pediatric insomnia symptoms, controlling for child age, family income, and SDB symptoms. *p < .05.

Table III.

Mediation Models Predicting Pediatric Insomnia Symptoms

| Consequent |

Indirect effect |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (household chaos) |

M2 (sleep knowledge) |

M3 (caregiver sleep) |

Y (pediatric insomnia) |

||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Estimate (bootstrapped 95% CI) |

| X (PARYC) | −.010 | .003 | .005 | .001 | .001 | .657 | −.001 | .021 | .956 | −.013 | .008 | .084 | |

| Child age | −.106 | .053 | .048 | −.021 | .017 | .901 | −.009 | .338 | .979 | −.241 | .121 | .050 | |

| SDBS | .776 | .381 | .044 | .066 | .122 | .592 | 6.253 | 2.428 | .011 | 1.610 | .885 | .073 | |

| Income | −.007 | .036 | .842 | .026 | .012 | .025 | −.056 | .231 | .807 | .062 | .083 | .457 | |

| M1 | −.090 | .216 | .678 | .001 (−.003, .006) | |||||||||

| M2 | .054 | .660 | .935 | .001 (−.003, .006) | |||||||||

| M3 | .087 | .034 | .012 | −.001 (−.003, .002) | |||||||||

| Constant | 3.624 | .469 | <.001 | .283 | .151 | .062 | 5.778 | 2.988 | .056 | 3.226 | 1.313 | .016 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| R 2 = .116 | R 2 = .050 | R 2 = .056 | R 2 = .144 | Total indirect = .001 (−.005, .008) | |||||||||

| F(4, 114) = 3.739, p = .007 | F(4, 114) = 1.504, p = .206 | F(4, 114) = 1.694, p = .156 | F(7, 111) = 2.662, p = .014 | ||||||||||

PARYC = Parenting Young Children; SDBS = Sleep Disordered Breathing Scale.

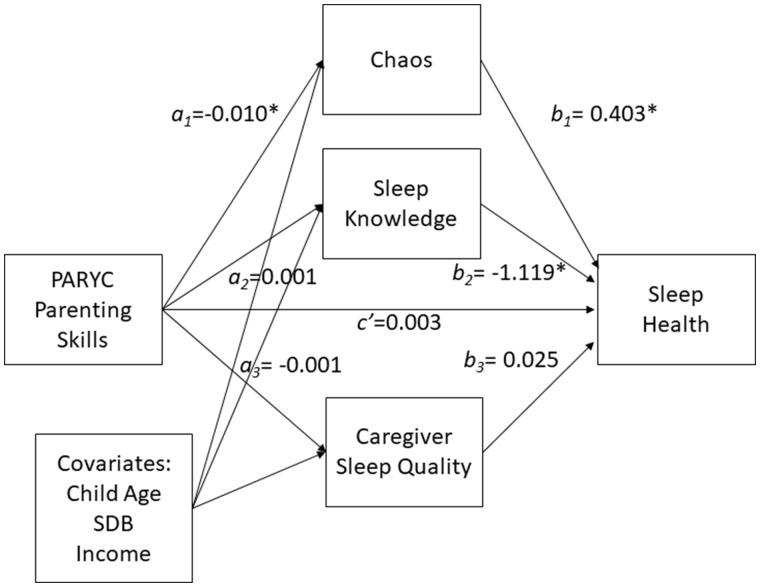

Parenting skills were indirectly linked to poor sleep health through increased chaos in the home. Caregivers reporting more positive parenting skills also reported lower household chaos (a1 = −.010, p = .005), which was linked to fewer poor sleep health behaviors (b1 = .403, p =.034; Figure 2; Table IV). The completely standardized indirect effect size was small (effect = −.053, SE = .029, 95% bootstrapped CI −.134, −.011). A bias corrected bootstrap CI for the indirect effect (ab = −.004) based on 10,000 bootstrap samples was entirely below zero (−.010 to −.001). There was no evidence that parenting was linked to poor sleep health independent of its association with household chaos, caregiver sleep knowledge, or caregiver sleep (c’ = .003, p = .663). There was no evidence of indirect effects of parenting skills on child sleep health through sleep knowledge or caregiver sleep.

Figure 2.

Parallel mediation model testing chaos, sleep knowledge, and caregiver sleep quality as mediators between parenting and sleep health, controlling for child age, family income, and SDB symptoms. *p < .05.

Table IV.

Mediation Models Predicting Sleep Health

| Consequent |

Indirect effects |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 (household chaos) |

M2 (sleep knowledge) |

M3 (caregiver sleep) |

Y (sleep health) |

||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Coefficient | SE | p | Estimate (bootstrapped 95% CI) |

| X (PARYC) | −.010 | .003 | .005 | .001 | .001 | .657 | −.001 | .021 | .956 | .003 | .007 | .614 | |

| Age | −.106 | .053 | .048 | −.002 | .017 | .901 | −.009 | .337 | .979 | .032 | .105 | .760 | |

| SDBS | .776 | .381 | .044 | .066 | .122 | .591 | 6.253 | 2.428 | .011 | .248 | .770 | .748 | |

| Income | −.007 | .036 | .842 | .026 | .012 | .025 | −.056 | .231 | .807 | .033 | .072 | .646 | |

| M1 | .401 | .187 | .034 | −.004 (−.010, .001) | |||||||||

| M2 | −1.118 | .571 | .053 | −.001 (−.005, .002) | |||||||||

| M3 | .025 | .029 | .407 | .001 (−.002, .002) | |||||||||

| Constant | 3.624 | .469 | <.0001 | .283 | .151 | .062 | 5.778 | 2.988 | .056 | .847 | 1.127 | .458 | |

|

| |||||||||||||

| R 2 = .116 | R 2 = .050 | R 2 = .056 | R 2 = .087 | Total indirect = −.004 (−.011, −.001) | |||||||||

| F(4, 114) = 3.739, p = .007 | F(4, 114) = 1.504, p = .206 | F(4, 114) = 1.694, p = .156 | F(7, 111) = 1.513, p = .170 | ||||||||||

PARYC = Parenting Young Children; SDBS = Sleep Disordered Breathing Scale.

Discussion

This study assessed potential mechanisms between parenting and child sleep health in a sample of young children from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds of lower SES to guide future interventions seeking to address early childhood sleep health in diverse samples. We examined whether household chaos, caregiver sleep knowledge, and caregiver sleep quality contributed to the relationship between positive parenting practices and two indices of child sleep: pediatric insomnia symptoms and sleep health. After controlling for child age, SDB symptoms, and household income, household chaos emerged as a potential mediator of the relationship between parenting and sleep health. No potential mediators contributed to the pediatric insomnia model.

Parenting interventions that seek to improve child sleep health should include strategies to address household chaos. Average household chaos in the current sample (m = 2.09, SD = 0.63) was similar to a prior study examining sleep and the family environment in a Head Start sample (m = 2.4, SD = 0.7, Boles et al., 2017). In the current sample, less than half of families endorsed consistent bedtimes or bedtime routines most nights, similar to previous research showing fewer bedtime routine behaviors in racial/ethnic minority children (Hale et al., 2009). For families with more chaotic work schedules and living arrangements, interventions should support families in developing consistent routines with age appropriate bedtimes that can be implemented with regularity despite variations in night-to-night caregiving and schedules. It was surprising that parenting skills were not related directly or indirectly to insomnia. This may be due to the measure of parenting skills that taps into more global positive parenting rather than specific behaviors related to managing child sleep. Social desirability could also contribute to parental responses to this measure, resulting in decreased variability in parenting practices in this sample.

Caregiver knowledge and child sleep health were significantly related in this study, consistent with prior research (McDowall et al., 2017), but knowledge did not contribute to the link between parenting skills and sleep health. These results suggest that knowledge is related to child sleep health independent of parenting skills. Knowledge has the potential to shift the caregiver’s desire to change their child’s sleep (Jones et al., 2013), but interventions that solely provide knowledge have not been able to produce durable behavior change in a diverse sample of preschool children (Wilson et al., 2014). Because this study models are cross-sectional, we cannot assess whether knowledge was a necessary condition for the relationship between parenting skills and sleep outcomes. Future research should examine these relationships and whether increasing caregiver sleep knowledge is necessary to improve child sleep (i.e., understanding why a regular bedtime is so important) or whether caregivers only need to learn strategies (i.e., how to follow a consistent bedtime routine) to improve child sleep outcomes.

Caregiver sleep quality did not significantly contribute to either model, although the results suggest that the quality of caregiver sleep is related to child sleep. Caregivers who reported more sleep problems also reported that their children experienced more symptoms of insomnia, consistent with prior research (Staples, Bates, Petersen, McQuillan, & Hoyniak, 2019). Unfortunately, the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to test for directionality. It may be that caregivers with poor sleep quality are less likely to establish good sleep health habits for their children. On the other hand, it is possible that child insomnia symptoms cause poor caregiver sleep because children may need caregivers to return to sleep at night, although research has yet to examine this association. It could also be that poor sleep quality in caregivers is reflective of additional family stress (McQuillan et al., 2019) or caregiver mood concerns, especially given that sleep disruption is a symptom of mood concerns like depression. Of note, longitudinal research has demonstrated a bidirectional association between child sleep problems and maternal depressive symptoms, with more evidence for child sleep problems driving subsequent maternal depression (Ystrom, Nilsen, Hysing, Sivertsen, & Ystrom, 2017). For families presenting with child symptoms of insomnia, clinicians should assess the impact of child sleep on caregiver sleep, assess for additional caregiver mood concerns, and consider the link between child and caregiver sleep as a secondary intervention target.

Poor sleep health behaviors were common in the current sample (94.1%). The most common poor sleep health behavior in our sample was access to one or more electronic devices in the child’s bedroom. More than three-quarters of our sample endorsed having electronic devices in the child’s bedroom, which is substantially higher than prior reports of devices in 17–46% of children’s bedrooms (Cabana et al., 2006; Cespedes et al., 2014; Mindell, Meltzer, Carskadon, & Chervin, 2009; Moorman & Harrison, 2019; Williamson & Mindell, 2019). On the sleep knowledge measure more than half of caregivers agreed (32.8%) or were unsure (25.2%) if “screen time before bed relaxes children so that they may fall asleep easier.” Because screen time has been consistently implicated in poor sleep health outcomes (Hale & Guan, 2015), further education around electronics and sleep may be necessary. Insomnia symptoms were less common than in Williamson and Mindell’s sample (55.5% vs. 62.7%, respectively). Given this symptom rate, this study may have been limited in detecting significant mediators.

This study provides important insight into mechanisms linking parenting skills and child sleep in a sample of racial/ethnic minority preschool children of lower SES. Limitations of the data include the cross-sectional data collected from one early childhood education center that do not allow us to test for causation. As previously noted, without longitudinal data we are unable to determine the directionality of relationships described in this study. The reliance on caregiver report is also a limitation as it may under-identify parenting challenges and sleep problems. The true/false nature of the Parental Knowledge and Attitudes measure may also limit its accuracy in assessing caregivers’ knowledge. Future studies may assess parenting practices through behavioral observation to better identify areas for intervention. Actigraphy should also be utilized in future studies to provide additional data regarding total sleep time and awakenings. Further research is needed on the impact of other child and caregiver factors that may impact parenting skills and child sleep outcomes in diverse samples, such as caregiver mental health and stress exposure, child temperament, comorbid child daytime behavior concerns, and cultural factors such as sleep beliefs, acculturation, and country of origin. Future research should also examine associations between parenting and child sleep both within and across different racial/ethnic minority groups, including biracial children, and at different levels of SES to understand how race/ethnicity, culture, and SES may independently influence sleep.

These results support possible mediators of the relationship between parenting and sleep health and identify specific intervention targets for sleep health interventions in socio-demographically diverse young children from lower SES backgrounds. Clinicians should consider the role of household chaos in discussing parenting interventions for child sleep. Community-based prevention and intervention efforts are needed to address sleep health in early childhood. Novel strategies for reaching families outside of hospitals and clinical practices are important to effectively disseminate evidence-based practice to children at risk for health disparities. Efforts to implement and evaluate evidence-based behavioral sleep interventions in primary care (Honaker & Saunders, 2018) and Head Start (Bonuck, Blank, True-Felt, & Chervin, 2016) are underway. Similarly, early childhood education centers offer a logical and relatively underutilized setting for health promoting interventions. Staff in early childhood centers report discussing sleep concerns with caregivers often (Bonuck, Schwartz, et al., 2016), yet few early childhood programs integrate sleep formally into curricula, despite ratings of high relevance to this age group (Bonuck, Collins-Anderson, Ashkinaze, Karasz, & Schwartz, 2019). Because families are in regular contact with early childhood center staff and staff indicate a desire to provide parents with support in their child’s sleep (Bonuck et al., 2019), daycare staff may be well positioned to reinforce intervention material and the daycare setting may be an effective model for the delivery of preventative interventions.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the families and family workers at the Early Learning Research Academy for their time and support of this study.

Funding

Dr. Ariel Williamson was supported by the Sleep Research Society Foundation and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD094905) during this study.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Footnotes

Reliability estimates for dichotomous insomnia and sleep health indexes and for the true–false sleep knowledge items are not presented as these items are not expected to be intercorrelated due to their disparate nature.

References

- Boles R. E., Halbower A. C., Daniels S., Gunnarsdottir T., Whitesell N., Johnson S. L. (2017). Family chaos and child functioning in relation to sleep problems among children at risk for obesity. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 15, 114–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K. A., Blank A., True-Felt B., Chervin R. (2016). Promoting sleep health among families of young children in head start: Protocol for a social-ecological approach. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K. A., Collins-Anderson A., Ashkinaze J., Karasz A., Schwartz A. (2019). Environmental scan of sleep health in early childhood programs. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 18,1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonuck K. A., Schwartz B., Schechter C. (2016). Sleep health literacy in head start families and staff: Exploratory study of knowledge, motivation, and competencies to promote healthy sleep. Sleep Health, 2, 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse D. J., Reynolds C. F., Monk T. H., Berman S. R., Kupfer D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI): A new instrument for psychiatric research and practice. Psychiatric Research, 28, 193–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana M. D., Slish K. K., Evans D., Mellins R. B., Brown R. W., Lin X., Clark N. M. (2006). Impact of physician asthma care education on patient outcomes. Pediatrics, 117, 2149–2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cespedes E. M., Gillman M. W., Kleinman K., Rifas-Shiman S. L., Redline S., Taveras E. M. (2014). Television viewing, bedroom television, and sleep duration from infancy to mid-childhood. Pediatrics, 133, e1163–e1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chervin R. D., Hedger K., Dillon J. E., Pituch K. J. (2000). Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ): Validity and reliability of scales for sleep-disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness, and behavioral problems. Sleep Medicine, 1, 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell J., Pike A., Dunn J. (2006). Household chaos–links with parenting and child behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 1116–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dush C. M. K., Schmeer K. K., Taylor M. (2013). Chaos as a social determinant of child health: Reciprocal associations? Social Science and Medicine, 95, 69–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M., Bagley E. J., Keiley M., Elmore-Staton L., Chen E., Buckhalt J. A. (2013). Economic adversity and children’s sleep problems: Multiple indicators and moderation of effects. Health Psychology, 32, 849–859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner M. A., Williams N. J., Knutson K. L., Roberts D., Jean-Louis G. (2016). Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Medicine, 18, 7–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guglielmo D., Gazmararian J. A., Chung J., Rogers A. E., Hale L. (2018). Racial/ethnic sleep disparities in US school-aged children and adolescents: A review of the literature. Sleep Health, 4, 68–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haack L. M., Gerdes A. C., Schneider B. W., Hurtado G. D. (2011). Advancing our knowledge of ADHD in Latino children: Psychometric and cultural properties of Spanish-versions of parental/family functioning measures. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39, 33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L., Berger L. M., LeBourgeois M. K., Brooks-Gunn J. (2009). Social and demographic predictors of preschoolers’ bedtime routines. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 30, 394–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale L., Guan S. (2015). Screen time and sleep among school-aged children and adolescents: A systematic literature review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 21, 50–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes A.F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honaker S. M., Saunders T. (2018). The Sleep Checkup: Sleep screening, guidance, and management in pediatric primary care. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 6, 201–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrin D. C., McGrath J. J., Quon E. C. (2014). Objective and subjective socioeconomic gradients exist for sleep in children and adolescents. Health Psychology, 33, 301–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. H., Owens J. A., Pham B. (2013). Can a brief educational intervention improve parents’ knowledge of healthy children’s sleep? A pilot-test. Health Education Journal, 72, 601–610. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir J., Sadeh A. (2013). Correspondence between reported and actigraphic sleep measures in preschool children: The role of a clinical context. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 09, 1147–1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozoff B., Askew G. L., Wolf A. W. (1996). Cosleeping and early childhood sleep problems: Effects of ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 17, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macıas J., Royuela A. (1996). La versión espanola del Índice de Calidad de Sueno de Pittsburgh. Informaciones Psiquiatricas, 146, 465–472. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. L., Moore R. H., Rosen C. L., Giordani B., Garetz S. L., Taylor H. G., Redline S. (2013). A randomized trial of adenotonsillectomy for childhood sleep apnea. New England Journal of Medicine, 368, 2366–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matheny A. P. Jr, Wachs T. D., Ludwig J. L., Phillips K. (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 429–444. [Google Scholar]

- McDowall P. S., Galland B. C., Campbell A. J., Elder D. E. (2017). Parent knowledge of children’s sleep: A systematic review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 31, 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEachern A. D., Dishion T. J., Weaver C. M., Shaw D. S., Wilson M. N., Gardner F. (2012). Parenting Young Children (PARYC): Validation of a self-report parenting measure. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 21, 498–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan M. E., Bates J. E., Staples A. D., Deater-Deckard K. (2019). Maternal stress, sleep, and parenting. Journal of Family Psychology, 33, 349–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer L. J., Mindell J. A. (2007). Relationship between child sleep disturbances and maternal sleep, mood, and parenting stress: A pilot study. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meltzer L. J., Mindell J. A. (2014). Systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions for pediatric insomnia. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39, 932–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller A. L., Miller S. E., LeBourgeois M. K., Sturza J., Rosenblum K. L., Lumeng J. C. (2019). Sleep duration and quality are associated with eating behavior in low-income toddlers. Appetite, 135, 100–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J., Kuhn B., Lewin D. S., Meltzer L. J., Sadeh A.; American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2006). Behavioral treatment of bedtime problems and night wakings in infants and young children. Sleep, 29, 1263–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J., Meltzer L. J., Carskadon M. A., Chervin R. D. (2009). Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: Findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Medicine, 10, 771–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J., Sadeh A., Wiegand B., How T. H., Goh D. Y. (2010). Cross-cultural differences in infant and toddler sleep. Sleep Medicine, 11, 274–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell J., Williamson A. A. (2018). Benefits of a bedtime routine in young children: Sleep, development, and beyond. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 40, 93–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman J. D., Harrison K. (2019). Beyond access and exposure: Implications of sneaky media use for preschoolers’ sleep behavior. Health Communication, 34, 529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick K. E., Millet G., Mindell J. A. (2016). Sleep differences by race in preschool children: The roles of parenting behaviors and socioeconomic status. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 14, 467–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadeh A. (2004). A Brief Screening Questionnaire for infant sleep problems: Validation and findings for an internet sample. Pediatrics, 113, e570–e577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwichtenberg A., Abel E. A., Keys E., Honaker S. M. (2019). Diversity in pediatric behavioral sleep intervention studies. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 47, 103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen B., Harvey A. G., Reichborn-Kjennerud T., Torgersen L., Ystrom E., Hysing M. (2015). Later emotional and behavioral problems associated with sleep problems in toddlers: A longitudinal study. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 575–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. P., Hardy S. T., Hale L. E., Gazmararian J. A. (2019). Racial disparities and sleep among preschool aged children: A systematic review. Sleep Health, 5, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples A. D., Bates J. E., Petersen I. T., McQuillan M. E., Hoyniak C. (2019). Measuring sleep in young children and their mothers: Identifying actigraphic sleep composites. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43, 278–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taveras E. M., Rifas-Shiman S. L., Bub K. L., Gillman M. W., Oken E. (2017). Prospective study of insufficient sleep and neurobehavioral functioning among school-age children. Academic Pediatrics, 17, 625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavernier R., Adam E. K. (2017). Text message intervention improves objective sleep hours among adolescents: The moderating role of race-ethnicity. Sleep Health, 3, 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A. A., Mindell J. A. (2019). Cumulative socio-demographic risk factors and sleep outcomes in early childhood. Sleep, 43, zsz233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. E., Miller A. L., Bonuck K., Lumeng J. C., Chervin R. D. (2014). Evaluation of a sleep education program for low-income preschool children and their families. Sleep, 37, 1117–1125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ystrom H., Nilsen W., Hysing M., Sivertsen B., Ystrom E. (2017). Sleep problems in preschoolers and maternal depressive symptoms: An evaluation of mother-and child-driven effects. Developmental Psychology, 53, 2261–2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]