Abstract

目的

探讨Sonic hedgehog(Shh)信号通路相关的单核苷酸多态性(single-nucleotide polymorphism, SNP)与非综合征型唇腭裂(non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate, NSCL/P) 之间的关联,并对唇腭裂疾病的致病风险因素进行探索。

方法

收集197例个体的外周血(NSCL/P患者100例,健康对照97例),基于国际人类基因组单体型图计划中中国北京汉族人口数据,使用Haploview软件进行单倍体型分析和标签SNP选择。针对Shh 信号通路中的4个候选基因SHH、PTCH1、SMO和GLI2共选择了27个SNP。使用Sequenom质谱技术检测27个SNP在4个Shh信号通路中候选基因的基因型,并进行分析。

结果

所选择的SNP基本涵盖了候选基因的潜在功能性SNP,其最小等位基因频率(minor allele frequency,MAF)>0.05:GLI2 73.5%, PTCH1 91.0%, SMO 100.0%, SHH 75.0%。发现位于SMO基因的SNP(rs12674259)和位于PTCH1基因的SNP(rs2066836)的基因型频率在NSCL/P病例组和对照组之间的差异有统计学意义。同时在4个候选基因所在的3条染色体(第2、7、9号染色体)中均发现了连锁不平衡,但在连锁不平衡单倍体型分析中,病例组和对照组之间的差异无统计学意义。

结论

提示Shh信号通路参与NSCL/P的发生,其信号通路中关键基因的某些特殊SNP位点与唇腭裂相关,为NSCL/P的病因研究提供了新的探索方向,可能为NSCL/P的早期筛查与风险预测提供帮助。

Keywords: 非综合征型唇腭裂, Sonic hedgehog, 单核苷酸多态性, 质谱检测

Abstract

Objective

To study the relationship between Sonic hedgehog (Shh) associated single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate (NSCL/P), and to explore the risk factors of cleft lip and/or palate. Many studies suggest that the pathogenesis of NSCL/P could be related to genes that control early development, in which the Shh signaling pathway plays an important role.

Methods

Peripheral blood was collected from 197 individuals (100 patients with NSCL/P and 97 healthy controls). Haploview software was used for haplotype analysis and Tag SNP were selected, based on the population data of Han Chinese in Beijing of the international human genome haplotype mapping project. A total of 27 SNP were selected for the 4 candidate genes of SHH, PTCH1, SMO and GLI2 in the Shh signaling pathway. The genotypes of 27 SNP were detected and analyzed by Sequenom mass spectrometry. The data were analyzed by chi-squared test and an unconditional Logistic regression model.

Results

The selected SNP basically covered the potential functional SNP of the target genes, and its minimum allele frequency (MAF) was >0.05: GLI2 73.5%, PTCH1 91.0%, SMO 100.0%, and SHH 75.0%. It was found that the genotype frequency of SNP (rs12674259) located in SMO gene and SNP (rs2066836) located in PTCH1 gene were significantly different between the NSCL/P group and the control group. Linkage disequilibrium was also found on 3 chromosomes (chromosomes 2, 7 and 9) where the 4 candidate genes were located. However, in the analysis of linkage imbalance haplotype, there was no significant difference between the disease group and the control group.

Conclusion

In China, NSCL/P is the most common congenital disease in orofacial region. However, as it is a multigenic disease and could be affected by multiple factors, such as the external environment, the etiology of NSCL/P has not been clearly defined. This study indicates that Shh signaling pathway is involved in the occurrence of NSCL/P, and some special SNP of key genes in this pathway are related to cleft lip and/or palate, which provides a new direction for the etiology research of NSCL/P and may provide help for the early screening and risk prediction of NSCL/P.

Keywords: Non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate, Sonic hedgehog, Single-nucleotide polymorphism, Sequennom massarray

唇腭裂是人类最常见的先天性发育畸形之一,同时也是口腔颌面部最常见的发育畸形,不仅影响患儿容貌,也会对患儿的发音、咀嚼和吞咽等产生不良影响。临床上根据是否伴有其他系统畸形或先天发育异常将其分为综合征型唇腭裂和非综合征型唇腭裂(non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate, NSCL/P)。NSCL/P在国内活产儿中的发病率大约为1.62‰[1],高于西方国家1.42‰的发病率[2]。

从病因学角度来看,NSCL/P受多基因影响且与环境因素有关[3]。通常认为影响胚胎发育,调控颌面部或腭板相关细胞的增殖、分化、凋亡的基因与唇腭裂的相关性更高。研究证实多个基因与唇腭裂相关[4,5],不同的信号通路均参与调控唇腭部的发育[6],然而具体调控机制目前尚无定论。迄今为止与胚胎早期发育相关的多个基因和信号通路已被证实在NSCL/P的发生中发挥作用,我们此前的研究显示血清中RBP4表达水平的下降和维生素A缺乏与新生儿的唇腭裂有关[7]。

在众多信号通路中,Sonic hedgehog(Shh)信号通路在生长发育尤其是胚胎早期发育过程中扮演着重要角色[8,9]。Shh信号通路影响脊椎动物早期发育阶段的细胞行为[10]、胚胎分化、组织发育和器官形成[8]。在早期胚胎发育过程中,Shh首先出现在中胚层[11],人或鼠的Shh信号通路变异会导致神经板形成异常[12,13]。Shh信号通路包括分泌蛋白Hedgehog(HH),跨膜蛋白受体Patched-1(PTCH1),跨膜蛋白Smoothened(SMO)以及下游的转录因子GLI1、GLI2、GLI3[14]。在致病基因的相关研究中,单核苷酸多态性(single-nucleotide polymorphism, SNP)是最常见的基因影响疾病发生发展的方式之一[15]。此外标签SNP在研究中日益广泛的应用使得SNP的检测更加高效,成本更低[16]。本研究采取基于SNP分析的方法检测Shh信号通路在NSCL/P和健康人群之间的差异,以期找到其与NSCL/P的关联。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 病例收集与对照

病例收集自全国多中心的口腔医院(包括重庆、甘肃、山东)。病例组为100例均已经过完善的临床检查并确诊为NSCL/P的患病者,无其他出生缺陷。对照组为97例未患NSCL/P也无其它出生缺陷的健康人群。本研究获得北京大学口腔医院生物医学伦理委员会审查批准(批件号:PKUSSIRB-201520012), 由纳入本研究的未成年对象的监护人签署知情同意书。

1.2. 选择标签SNP

基于国际人类基因组单体型图计划中中国北京汉族人口数据,使用Haploview软件(ver.4.2, Mark Daly博士实验室, 美国)进行单倍体型分析和标签SNP选择。针对Shh 信号通路中的4个候选基因SHH、PTCH1、SMO和GLI2共设计了27个SNP。所选择的SNP基本涵盖了候选基因的潜在功能性SNP,其最小等位基因频率(minor allele frequency, MAF)>0.05:GLI2 73.5%, PTCH1 91.0%, SMO 100.0%, SHH 75.0%。

1.3. 基因型检测

使用基因组DNA提取试剂盒(天根公司,北京)从外周血样中提取基因组DNA。采用Mass-ARRAY分子量阵列技术进行多重引物和PCR设计,并结合基于基质辅助激光解吸电离飞行时间质谱技术 (matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight, MALDI-TOF)的Sequenom质谱检测技术(Sequenom公司, 美国)[17],检测27个SNP位点在4个候选基因的基因型。所有基因型检测结果经过重复验证以保证结果的准确性,一致性达到95%。

1.4. 统计学分析

计数资料(等位基因、基因型分布频率等)采用成组设计四格表资料的卡方检验进行比较。计算每个SNP在病例组和对照组中出现的比值比(odds ratio,OR)和95%置信区间(confidence interval,CI)表示关联强度。对基因型频率与唇腭裂的相关性进行多重检验,包括Logistic线性回归模型[18],同时使用Bonferroni校正以降低假阳性率。病例组和对照组中每个SNP都通过基因型分布频率的卡方检验进行哈迪-温伯格平衡(Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium,HWE)分析。并使用软件Haploview(http://www.broad.mit.edu/mpg/haploview;[19])进行连锁不平衡统计。

2. 结果

2.1. SNP等位基因及基因型频率在病例组和对照组之间的比较分析

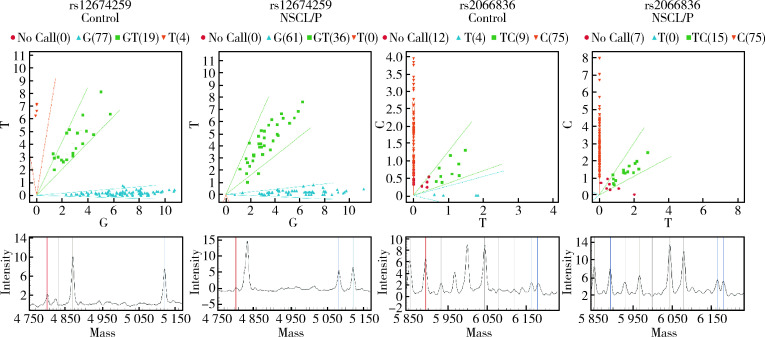

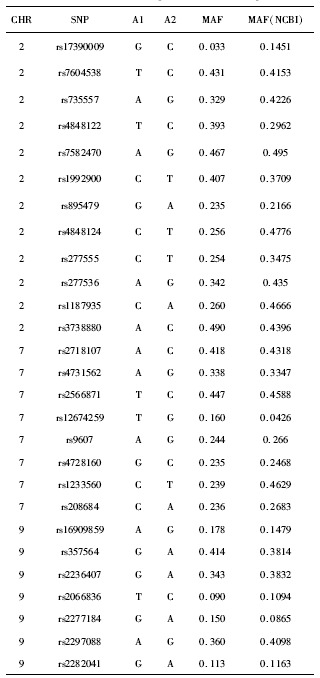

27个SNP中,检出率超过90%的有25个,另外两个位于GLI2的rs4848122 和rs17390009的检出率分别为76.6%和78.2%被剔除。27个SNP的MAF如表1所示,所有SNP的HWE检验分析数据见表2(P>0.01)。我们使用卡方检验(表3)和Logistic回归分析(表4)对等位基因进行统计,得出疾病组与对照组的差异无统计学意义。然而对基因型的病例对照分析则显示rs12674259(SMO)和rs2066836(PTCH1)的基因型频率在病例组和对照组之间的差异有统计学意义(表5),这两个位点的分布频率和质谱峰值如图1所示。

1.

27个SNP的最小等位基因频率

Minor allele frequencies of SNP in samples

|

2.

27个SNP的哈迪-温伯格平衡检验结果

Tests of HWE for all SNP

| CHR | SNP | A1 | A2 | GENO(A1A1/A1A2/A2A2) | P |

| CHR, chromosome; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; A1, minor allele; A2, major allele; GENO, genotype. | |||||

| 2 | rs17390009 | G | C | 0/4/67 | 1.000 |

| 2 | rs7604538 | T | C | 19/46/31 | 0.836 |

| 2 | rs735557 | A | G | 11/42/42 | 1.000 |

| 2 | rs4848122 | T | C | 13/40/32 | 1.000 |

| 2 | rs7582470 | A | G | 23/40/34 | 0.104 |

| 2 | rs1992900 | C | T | 14/48/33 | 0.674 |

| 2 | rs895479 | G | A | 3/39/55 | 0.266 |

| 2 | rs4848124 | C | T | 3/39/53 | 0.261 |

| 2 | rs277555 | C | T | 4/40/52 | 0.414 |

| 2 | rs277536 | A | G | 13/39/42 | 0.493 |

| 2 | rs1187935 | C | A | 7/31/48 | 0.577 |

| 2 | rs3738880 | A | C | 21/52/23 | 0.540 |

| 7 | rs2718107 | A | C | 22/38/35 | 0.093 |

| 7 | rs4731562 | A | G | 8/43/43 | 0.638 |

| 7 | rs2566871 | T | C | 24/41/32 | 0.154 |

| 7 | rs12674259 | T | G | 4/19/77 | 0.062 |

| 7 | rs9607 | A | G | 5/37/52 | 0.786 |

| 7 | rs4728160 | G | C | 3/37/55 | 0.385 |

| 7 | rs1233560 | C | T | 1/40/56 | 0.038 |

| 7 | rs208684 | C | A | 4/33/58 | 1.000 |

| 9 | rs16909859 | A | G | 5/22/73 | 0.069 |

| 9 | rs357564 | G | A | 21/39/33 | 0.204 |

| 9 | rs2236407 | G | A | 12/42/43 | 0.821 |

| 9 | rs2066836 | T | C | 0/15/75 | 1.000 |

| 9 | rs2277184 | G | A | 2/20/75 | 0.632 |

| 9 | rs2297088 | A | G | 13/42/42 | 0.657 |

| 9 | rs2282041 | G | A | 1/22/74 | 1.000 |

3.

对照组和病例组的SNP卡方检验

Chi-squared analysis of allele in controls and NSCL/P patients

| SNP | A1 | A2 | CHISQ | P | OR | SE | 95%CI | ||||

| SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; A1, minor allele; A2, major allele; SE, standard error; CHISQ, chi-square test. | |||||||||||

| rs17390009 | G | C | 0.605 | 0.437 | 1.736 | 0.718 | 0.425-7.086 | ||||

| rs7604538 | T | C | 0.044 | 0.833 | 0.956 | 0.214 | 0.629-1.454 | ||||

| rs735557 | A | G | 0.138 | 0.710 | 0.919 | 0.227 | 0.589-1.434 | ||||

| rs4848122 | T | C | 0.869 | 0.351 | 1.256 | 0.245 | 0.777-2.031 | ||||

| 2 | rs4848124 | C | T | 0.256 | 0.4776 | ||||||

| 2 | rs277555 | C | T | 0.254 | 0.3475 | ||||||

| 2 | rs277536 | A | G | 0.342 | 0.435 | ||||||

| 2 | rs1187935 | C | A | 0.260 | 0.4666 | ||||||

| 2 | rs3738880 | A | C | 0.490 | 0.4396 | ||||||

| 7 | rs2718107 | A | C | 0.418 | 0.4318 | ||||||

| 7 | rs4731562 | A | G | 0.338 | 0.3347 | ||||||

| 7 | rs2566871 | T | C | 0.447 | 0.4588 | ||||||

| 7 | rs12674259 | T | G | 0.160 | 0.0426 | ||||||

| 7 | rs9607 | A | G | 0.244 | 0.266 | ||||||

| 7 | rs4728160 | G | C | 0.235 | 0.2468 | ||||||

| 7 | rs1233560 | C | T | 0.239 | 0.4629 | ||||||

| 7 | rs208684 | C | A | 0.236 | 0.2683 | ||||||

| 9 | rs16909859 | A | G | 0.178 | 0.1479 | ||||||

| 9 | rs357564 | G | A | 0.414 | 0.3814 | ||||||

| 9 | rs2236407 | G | A | 0.343 | 0.3832 | ||||||

| 9 | rs2066836 | T | C | 0.090 | 0.1094 | ||||||

| 9 | rs2277184 | G | A | 0.150 | 0.0865 | ||||||

| 9 | rs2297088 | A | G | 0.360 | 0.4098 | ||||||

| 9 | rs2282041 | G | A | 0.113 | 0.1163 | ||||||

4.

病例组和对照组的Logistic回归分析

Logistic tests of association in controls and NSCL/P patients

| CHR | SNP | A1 | A2 | OR | SE | 95%CI | P |

| CHR, chromosome;SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; A1, minor allele; A2, major allele; SE, standard error. | |||||||

| 2 | rs17390009 | G | C | 2.173 | 0.746 | 0.503-9.380 | 0.298 |

| 2 | rs17390009 | G | C | 2.173 | 0.746 | 0.503-9.380 | 0.298 |

| 2 | rs7604538 | T | C | 0.960 | 0.212 | 0.634-1.453 | 0.846 |

| 2 | rs735557 | A | G | 0.902 | 0.224 | 0.582-1.398 | 0.644 |

| 2 | rs4848122 | T | C | 1.266 | 0.243 | 0.787-2.037 | 0.331 |

| 2 | rs7582470 | A | G | 1.041 | 0.202 | 0.701-1.545 | 0.843 |

| 2 | rs1992900 | C | T | 1.146 | 0.230 | 0.731-1.796 | 0.553 |

| 2 | rs895479 | G | A | 0.947 | 0.259 | 0.570-1.573 | 0.834 |

| 2 | rs4848124 | C | T | 1.387 | 0.261 | 0.832-2.312 | 0.209 |

| 2 | rs277555 | C | T | 1.125 | 0.254 | 0.684-1.850 | 0.644 |

| 2 | rs277536 | A | G | 0.974 | 0.227 | 0.625-1.518 | 0.907 |

| 2 | rs1187935 | C | A | 0.975 | 0.247 | 0.601-1.583 | 0.920 |

| 2 | rs3738880 | A | C | 1.004 | 0.209 | 0.666-1.513 | 0.986 |

| 7 | rs2718107 | A | C | 0.882 | 0.209 | 0.586-1.329 | 0.549 |

| 7 | rs4731562 | A | G | 1.374 | 0.245 | 0.850-2.221 | 0.195 |

| 7 | rs2566871 | T | C | 0.888 | 0.207 | 0.592-1.333 | 0.567 |

| 7 | rs12674259 | T | G | 0.696 | 0.298 | 0.388-1.249 | 0.225 |

| 7 | rs9607 | A | G | 0.861 | 0.253 | 0.525-1.413 | 0.553 |

| 7 | rs4728160 | G | C | 1.003 | 0.255 | 0.608-1.653 | 0.991 |

| 7 | rs1233560 | C | T | 1.450 | 0.271 | 0.852-2.466 | 0.171 |

| 7 | rs208684 | C | A | 1.206 | 0.247 | 0.744-1.955 | 0.447 |

| 9 | rs16909859 | A | G | 0.752 | 0.251 | 0.460-1.231 | 0.257 |

| 9 | rs357564 | G | A | 0.871 | 0.207 | 0.581-1.308 | 0.507 |

| 9 | rs2236407 | G | A | 0.981 | 0.227 | 0.629-1.529 | 0.931 |

| 9 | rs2066836 | T | C | 1.224 | 0.358 | 0.607-2.467 | 0.572 |

| 9 | rs2277184 | G | A | 1.475 | 0.297 | 0.825-2.637 | 0.190 |

| 9 | rs2297088 | A | G | 1.043 | 0.215 | 0.684-1.589 | 0.846 |

| 9 | rs2282041 | G | A | 0.666 | 0.346 | 0.338-1.313 | 0.241 |

5.

病例组与对照组的统计关联

Association statistics of the NSCL/P and control panels

| SNP | Genotype | Control | NSCL/P | OR (95%CI) | P(OR) | P(Logistic) | P(Bonferroni) | P(HWE) | |||||||

| SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism; NSCL/P, non-syndromic cleft lip and/or palate; P (Logistic), ajusted with gender; P (Bonferroni), ajus-ted P value by Bonferroni correction; P (HWE), ajusted P value by HWE test; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. | |||||||||||||||

| rs12674259 | G/G | 77 (77%) | 61 (62.9%) | 1 | |||||||||||

| G/T | 19 (19%) | 36 (37.1%) | 0.42 (0.22-0.81) | 0.0017 | 0.0016 | 0.043 | 0.062 | ||||||||

| T/T | 4 (4%) | 0 (0%) | NA (0.00-NA) | ||||||||||||

| rs7582470 | A | G | 0.062 | 0.804 | 1.054 | 0.213 | 0.695-1.599 | ||||||||

| rs1992900 | C | T | 0.337 | 0.561 | 1.134 | 0.217 | 0.742-1.735 | ||||||||

| rs895479 | G | A | 0.088 | 0.767 | 0.930 | 0.247 | 0.573-1.507 | ||||||||

| rs4848124 | C | T | 1.851 | 0.174 | 1.402 | 0.249 | 0.861-2.283 | ||||||||

| rs277555 | C | T | 0.375 | 0.540 | 1.162 | 0.246 | 0.718-1.882 | ||||||||

| rs277536 | A | G | 0.000 | 0.989 | 1.003 | 0.225 | 0.646-1.559 | ||||||||

| rs1187935 | C | A | 0.001 | 0.974 | 0.992 | 0.253 | 0.604-1.628 | ||||||||

| rs3738880 | A | C | 0.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.211 | 0.661-1.512 | ||||||||

| rs2718107 | A | C | 0.347 | 0.556 | 0.881 | 0.215 | 0.578-1.343 | ||||||||

| rs4731562 | A | G | 1.596 | 0.207 | 1.336 | 0.229 | 0.852-2.093 | ||||||||

| rs2566871 | T | C | 0.304 | 0.581 | 0.890 | 0.212 | 0.587-1.348 | ||||||||

| rs12674259 | T | G | 1.527 | 0.217 | 0.698 | 0.292 | 0.393-1.237 | ||||||||

| rs9607 | A | G | 0.450 | 0.503 | 0.846 | 0.250 | 0.519-1.380 | ||||||||

| rs4728160 | G | C | 0.001 | 0.973 | 0.992 | 0.250 | 0.607-1.619 | ||||||||

| rs1233560 | C | T | 1.640 | 0.200 | 1.380 | 0.252 | 0.842-2.261 | ||||||||

| rs208684 | C | A | 0.790 | 0.374 | 1.248 | 0.250 | 0.765-2.035 | ||||||||

| rs16909859 | A | G | 1.489 | 0.222 | 0.714 | 0.277 | 0.415-1.228 | ||||||||

| rs357564 | G | A | 0.479 | 0.489 | 0.860 | 0.218 | 0.561-1.318 | ||||||||

| rs2236407 | G | A | 0.002 | 0.965 | 1.010 | 0.221 | 0.655-1.558 | ||||||||

| rs2066836 | T | C | 0.310 | 0.578 | 1.239 | 0.386 | 0.581-2.642 | ||||||||

| rs2277184 | G | A | 2.396 | 0.122 | 1.588 | 0.300 | 0.881-2.859 | ||||||||

| rs2297088 | A | G | 0.114 | 0.736 | 1.077 | 0.219 | 0.701-1.653 | ||||||||

| rs2282041 | G | A | 1.227 | 0.268 | 0.686 | 0.342 | 0.351-1.340 | ||||||||

1.

rs2066836和rs12674259的Sequenom质谱测序结果

Distribution frequency and multiplex polymerase chain reaction

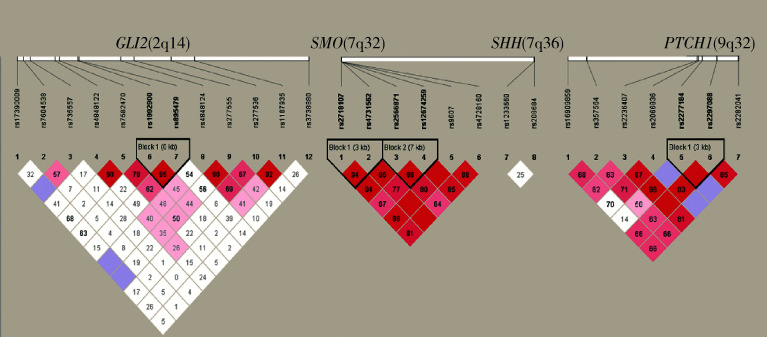

2.2. 候选基因的连锁不平衡分析

在4个候选基因所位于的3条目标染色体(第2、7、9号染色体)中均发现了连锁不平衡(图2)。在连锁不平衡单倍体型分析中,病例组和对照组之间的差异无统计学意义。

2.

4个候选基因GLI2(2q14)、 SMO(7q32)、 SHH(7q36)和 PTCH1(9q22)的连锁不平衡分析

Linkage disequilibrium blocks in the GLI2(2q14), SMO(7q32), SHH(7q36) and PTCH1(9q22)

2.3. rs12674259和rs2066836的位点功能预测

本研究显示rs12674259和rs2066836位点频率在病例组和对照组中的差异具有统计学意义。rs2066836位点位于PTCH1基因的外显子区,针对该SNP位点进行的预测分析表明,其多态性可能会影响基因外显子区剪接位点的功能,进而改变剪接与转录过程。

与PTCH1类似,SMO也是Shh信号通路中的一个跨膜蛋白受体, rs12674259定位在内含子区,该位点可能是MIT/TFE3转录因子的结合位点,其多态性可能会通过转录因子结合位点的改变而影响基因转录。

3. 讨论

此前有研究显示综合征型唇腭裂与单个基因突变有关,其中包括组成Shh信号通路的GLI2、 GLI3、 PTCH1和 SHH,所以我们选择覆盖这4个候选基因的标签SNP进行检测,以探究在中国人群中Shh信号通路是否也与NSCL/P相关。本研究中我们分析了Shh信号通路中4个基因的27个SNP位点,并发现了PTCH1的SNP位点rs2066836和SMO的SNP位点rs12674259与唇腭裂相关。

PTCH1是颅颌面发育的重要调控因子,其单倍剂量不足可能会引发成釉细胞瘤[20]。另外,PTCH1突变可以导致唇腭裂的发生[21]。此前有研究显示位于PTCH1的SNP位点rs2066836与一个爱尔兰人群中唇腭裂的发生相关[22]。本研究表明这一位点与中国人群中唇腭裂发病相关。我们对该SNP位点进行功能预测,发现它是外显子区的多态性,可能会影响外显子区剪接位点的增加或缺失,改变剪接与转录过程,进而影响基因表达水平。

与PTCH1类似,SMO也是Shh信号通路中的一个跨膜蛋白受体,SMO缺乏可能引起软骨丧失和颅骨发育缺陷[23,24]。此前未见rs12674259的相关报道,它定位在内含子区,可能是转录因子结合位点,该位点的多态性可能导致转录因子结合位点的改变而影响基因转录。

此前有研究认为位于2号染色体上的基因GLI2与唇腭裂发生有关[15],然而本次研究没有发现二者的相关性,其中一个原因可能是样本量不足,人群差异也可能导致研究结果不一致,此前还没有在中国人群中的相关研究;另一个原因可能是SNP的选择方法不一样,我们希望用标签SNP最大限度反映所有SNP,这种方法实用且经济,但与传统方法相比可能会丢失部分信息。本研究中用来检测基因型的Sequenom质谱分析法是一种性价比较高的SNP检测方法,适用于样本量较大的病例对照研究,近年来越来越多的用于多基因疾病与SNP相关性的研究中[25,26]。

综上,本研究强调了整个Shh信号通路与唇腭裂的相关性研究,分析关键基因对疾病的贡献度和它们之间的关联,发现了中国人群中PTCH1和SMO的两个SNP位点与唇腭裂的关联,表明Shh信号通路与唇腭裂的发生相关[27,28,29],可以从新的角度帮助阐明唇腭裂发病机制,然而其具体作用机制目前还不清楚,需要未来设计实验进一步探究。

(本文编辑:刘淑萍)

Biographies

林久祥,博士、资深教授、主任医师,北京大学口腔医学院颅面生长发育研究中心主任,《中华口腔正畸学杂志》总编辑,Tweed中国中心主席;是我国培养的口腔正畸专业第一位博士,1991年破格晋升教授、主任医师双职称,同年成为我国正畸界唯一获得国家教育委员会和国务院学位委员会授予的“做出突出贡献的中国博士学位获得者”,1992年获政府特殊津贴,1993年取得博士生导师资格,1998年被评为卫生部有突出贡献的中青年专家。曾任中华医学会正畸专业委员会主任委员;在国内外正畸界首次提出了“健康矫治(正畸)理念”,并研发出适宜实施该理念的传动矫正器及技术,后者2008年被卫生部评为“十年百项”适宜推广技术,与恒牙期骨性Ⅲ类牙颌畸形非手术矫治的突破一起,于2012年获中华医学科技奖二等奖、北京市科技成果二等奖,并于2014年在卫生部24项只选2项的竞争答辩中,胜出上报申请国家发明奖;2018年12月由Tweed中国中心授予“终身成就奖”。目前主要研究方向为非综合征型唇腭裂相关基础研究、传动矫正技术及健康矫治研究以及口腔颅颌面生长发育研究。

陈峰,北京大学口腔医学院副研究员、博士生导师。负责北京大学口腔医学院中心实验室微生物平台,是中华口腔医学会口腔生物医学专业委员会委员、口腔科研管理分会青年委员。担任Ebiomedicine等多家杂志审稿专家,近五年作为通信作者在Journal of Dental Research、Journal of Bone and Mineral Research、Oral Oncology、Frontiers in Microbiology、Protein & Cell等期刊发表SCI论文50余篇。主持国家自然科学基金面上项目在内的各级科研项目4项,参与获得北京市科学技术三等奖1项。2018年与北京大学基础医学院吴聪颖研究员联合申请获批北京大学医学交叉研究种子基金-中央高校基本科研业务费(ECM29基因突变在非综合征型唇腭裂发病中的作用与机制研究)。目前主要研究方向为颅颌面发育缺陷疾病(唇腭裂)的分子机制和口腔微生态(微生物宏基因组学与唾液蛋白组学)。

Funding Statement

北大医学交叉研究种子基金(BMU2018MX017)-中央高校基本科研业务费、北大医学青年科技创新培育基金(BMU2018PY025)-中央高校基本科研业务费、国家自然科学基金(81870747,81860194)

Supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities: Peking University Medicine Seed Fund for Interdisciplinary Research (BMU2018MX017), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities: Peking University Medicine Fund of Fostering Young Scholars’ Scientific & Technological Innovation (BMU2018PY025), and the National Natural Science Foundation(81870747,81860194)

Contributor Information

林 久祥 (Jiu-xiang LIN), Email: jxlin@pku.edu.cn.

陈 峰 (Feng CHEN), Email: chenfeng2011@hsc.pku.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Mossey PA, Little J, Munger RG, et al. Cleft lip and palate. Lancet. 2009;374(9703):1773–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, et al. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(3):167–178. doi: 10.1038/nrg2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lidral AC, Murray JC. Genetic approaches to identify disease genes for birth defects with cleft lip/palate as a model. Birth Defects Res B. 2004;70(12):893–901. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schliekelman P, Slatkin M. Multiplex relative risk and estimation of the number of loci underlying an inherited disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;71(6):1369–1385. doi: 10.1086/344779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ludwig KU, Mangold E, Herms S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analyses of nonsyndromic cleft lip with or without cleft palate identify six new risk loci. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):968–971. doi: 10.1038/ng.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marazita ML, Mooney MP. Current concepts in the embryology and genetics of cleft lip and cleft palate. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(2):125–140. doi: 10.1016/S0094-1298(03)00138-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Zhou S, Zhang Q, et al. Proteomic analysis of RBP4/vitamin A in children with cleft lip and/or palate. J Dent Res. 2014;93(6):547–552. doi: 10.1177/0022034514530397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu D, Helms JA. The role of sonic hedgehog in normal and abnormal craniofacial morphogenesis. Development. 1999;126(21):4873–4884. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vieira AR, Castilla EE, Ming JE, et al. Mutational analysis of the Sonic hedgehog gene in 220 newborns with oral clefts in a South American (ECLAMC) population. Am J Med Genet. 2002;108(1):12–15. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.10204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han J, Mayo J, Xu X, et al. Indirect modulation of Shh signaling by Dlx5 affects the oral-nasal patterning of palate and rescues cleft palate in Msx1-null mice. Development. 2009;136(24):4225–4233. doi: 10.1242/dev.036723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimamura K, Hartigan DJ, Martinez S, et al. Longitudinal organization of the anterior neural plate and neural tube. Development. 1995;121(12):3923–3933. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.12.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Belloni E, Muenke M, Roessler E, et al. Identification of Sonic hedgehog as a candidate gene responsible for holoprosencephaly. Nat Genet. 1996;14(3):353–356. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang C, Litingtung Y, Lee E, et al. Cyclopia and defective axial patterning in mice lacking Sonic hedgehog gene function. Nature. 1996;383(6599):407–413. doi: 10.1038/383407a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahnama F, Shimokawa T, Lauth M, et al. Inhibition of GLI1 gene activation by Patched1. Biochem J. 2006;394(Pt 1):19–26. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beaty TH, Fallin MD, Hetmanski JB, et al. Haplotype diversity in 11 candidate genes across four populations. Genetics. 2005;171(1):259–267. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xing J, Witherspoon DJ, Watkins WS, et al. HapMap tag SNP transferability in multiple populations: general guidelines. Genomics. 2008;92(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang L, Zhang C, Li Y, et al. A non-synonymous polymorphism Thr115Met in the EpCAM gene is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer in Chinese population. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;126(2):487–495. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ong KL, Li M, Tso AK, et al. Association of genetic variants in the adiponectin gene with adiponectin level and hypertension in Hong Kong Chinese. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;163(2):251–257. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, et al. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farias LC, Gomes CC, Brito JA, et al. Loss of heterozygosity of the PTCH gene in ameloblastoma. Hum Pathol. 2012;43(8):1229–1233. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2011.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen MM. Holoprosencephaly: clinical, anatomic, and molecular dimensions. Birth Defects Res. 2006;76(9):658–673. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter TC, Molloy AM, Pangilinan F, et al. Testing reported associations of genetic risk factors for oral clefts in a large Irish study population. Birth Defects Res. 2010;88(2):84–93. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brand M, Heisenberg CP, Warga RM, et al. Mutations affecting development of the midline and general body shape during zebrafish embryogenesis. Development. 1996;123(6):129–142. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eberhart JK, Swartz ME, Crump JG, et al. Early hedgehog signaling from neural to oral epithelium organizes anterior craniofacial development. Development. 2006;133(6):1069–1077. doi: 10.1242/dev.02281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yahya MJ, Ismail PB, Nordin NB, et al. CNDP1, NOS3, and MnSOD polymorphisms as risk factors for diabetic nephropathy among type 2 diabetic patients in Malaysia[J]. J Nutr Metab. 2019(3):1–13. doi: 10.1155/2019/8736215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhuo M, Zhuang X, Tang W, et al. Theimpact of IL-16 3’UTR polymorphism rs859 on lung carcinoma susceptibility among Chinese han individuals. Biomed Res Int. 2018;12(24):1–10. doi: 10.1155/2018/8305745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beaty TH, Hetmanski JB, Fallin MD, et al. Analysis of candidate genes on chromosome 2 in oral cleft case-parent trios from three populations. Hum Genet. 2006;120(4):501–518. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0235-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levi B, James AW, Nelson ER, et al. Role of Indian hedgehog signaling in palatal osteogenesis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(3):1182–1190. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182043a07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Helms JA, Kim CH, Hu D, et al. Sonic hedgehog participates in craniofacial morphogenesis and is down-regulated by teratogenic doses of retinoic acid. Dev Biol. 1997;187(1):1–35. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]