Abstract

Chitin and chitosan have been proved to have enormous applications in biomedical, pharmaceutical, and industrial fields. The horse mussel, Modiolus modiolus, a refuse of the fishery industries at Thondi, is a reserve of rich chitin. The aim of this work is to extract chitosan from the horse mussel and its further characterization using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), micro-Raman spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), and elemental analysis. The result of FTIR studies revealed different functional groups of organic compounds such as out-of-plane bending (564 cm–1), C–O–C stretching (711 cm–1), and CH2 stretching (1174 cm–1) in chitosan. The degree of acetylation of the extracted chitosan was observed to be 57.43%, which makes it suitable as a biopolymer for biomedical applications. Prominent peaks observed with micro-Raman studies were at 484 cm–1 (14,264 counts/s), 2138 cm–1 (45,061 counts/s), and 2447 cm–1 (45,636 counts/s). XRD studies showed the crystalline nature of the polymer, and the maximum peak was observed at 20.04°. Elemental analysis showed a considerable decrease in the percentage of nitrogen and carbon upon the conversion of chitin to chitosan, while chitosan had a higher percentage of hydrogen and sulfur. The antibacterial activities of chitosan from the horse mussel were found to be efficient at a 200 μg/mL concentration against all the bacterial strains tested with a comparatively higher antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli (9 mm) and Bacillus subtilis (8 mm).

Introduction

Studies to exploit biomaterials as an alternative to replace synthetic counterparts are still unfulfilled. Chitin is a linear biopolymer formed of 2-acetamide-2-deoxi-d-glucopyranose units linked by a β(1, 4) glycosidic bond. As per previous studies, chitin differs from cellulose in the presence of acetamide groups at C–Z positions. Depending upon the source, chitin is found as two allomorphs (α and β), among which α chitin is copiously formed within the exoskeleton of shellfish, especially from shrimps and crabs.1 Chitin and its derivatives have unique physical, chemical, and biological properties to vouch for their application as immunostimulant, anticoagulant, enzyme inhibitory, antimicrobial, anticancer, anticholesteremic, and wound-healing agent. They are also used as biosorbent materials in absorbing metal ions from polluted water.2

Chitosan, a biopolymer extracted from chitin, has extraordinary flexibility and offers credible outcomes of chemical alterations.3 Its sustainability, biodegradability, biocompatibility, nontoxicity, and adsorption empower it to have a wide extent of applications in pharmaceuticals, textiles, farming, beauty care products, food, and water treatment.4−10

Chitosan is extracted from chitin by hydrolysis of acetamide groups with concentrated NaOH or KOH (40–50%) at temperatures above 100 °C11 through the process of deacetylation.2,3,12 Four crystalline polymorphs may be framed by long chitosan chains: three hydrated and one anhydrous. The presence of group NH2 makes chitosan reactions more adaptable than cellulose reactions. At C6 and C3 positions,13 the chitosan reactivity is shown to occur because of the presence of free amino groups and primary and auxiliary hydroxyl bunches.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectra have been chosen invariably as a method to characterize chitosan based on different bands corresponding to the −NH2 group, which can be allocated to the symmetrical COO– gather extending vibration.9,14−22 The degree of acetylation (DA), on an average, ranges from 40 to 13%, while its molecular weight ranges from 105 to 106 Da and varies depending on the conditions of source and preparation. Raman spectroscopy has recognized the six-membered ring which contains oxygen and the characteristic peaks corresponding to chitosan.23 X-ray diffraction (XRD) studies have witnessed the sharpness of the bands of the chitin samples as compared to their derivative with a slight decrease within the crystalline percentage.24,25 The elemental analysis is insufficient to conclude about modifications achieved within the product.26,27

Studies of antimicrobial activities and properties of chitosan are expressed as a journey of scientific investigation and evolution of technology. Chitosan is an excellent antimicrobial substance against various microbial pathogens,28 and its products have a wide range of activities and a superior rate of killing different strains of bacteria.29,30 The antimicrobial activity of chitosan is affected by its solubility, which in turn is affected by the elevated quantities of free amino groups in the chain. The fundamental change in its chemical structure, low molecular weight, water solubility, and the degree of deacetylation (DDA) complements the antitumor behavior of chitosan.31 Raja et al.(18) tested the efficacy of chitosan derived from shrimp and crab shells to inhibit human pathogen growth by disseminating bacterial assays. Vinsova and Vavrikova13 have studied the antimicrobial, antitumor, and antioxidant role of chitosan derivatives.

The residues of the seafood industry, mainly crab shells and shrimp shells, form important resources for the extraction of chitin and chitosan. Studies of the extraction, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of chitosan in molluscs are limited.32 Rasti et al.(17) drew chitin and chitosan from mollusc and characterized them by soaking in 45% NaOH solution. Palpandi et al.(20) have extracted chitin and chitosan from the operculum of the mangrove gastropod Nerita crepidularia. Extraction and characterization of chitosan from the shells of the oysters, Mytilus edulis, and Laevicardium attenuatum has been carried out from separate continents.21 Low-molecular-weight sulfated chitosan (SP-LMWSC) was isolated from Sepia pharaonis(22) cuttlebone.

The horse mussel, Modiolus modiolus, is seen in small regions or in large beds with vast concentrations in the sublittoral region, where the byssus threads attach them to the hard substrate. The M. modiolus beds can be considered to be very secure habitats. Horse mussel beds are found in a wide range of depths from the lower shore to within an approximately 200 m depth.33 They are a dominant member of the shallow-water benthic communities and are a widely collected species along the Thondi coast. They have been chosen as the raw material for this work as they have become available in considerable amounts as by-catch and, being inedible, they are discarded as offshore waste. The deposits of these marine wastes in seashore and coastal areas pollute the environment. Exploitation of the mollusc waste for biomedical applications is highly warranted. With the aim to turn the shell waste into a useful product, this work was carried out to extract chitosan from the horse mussel (M. modiolus) and characterize chitosan by FTIR, micro-Raman spectroscopy, XRD, and elemental analysis. The antibacterial activity of the extracted chitosan was also tested against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Results and Discussion

Extraction of Chitosan

An average of 40.13 ± 1.25% of chitin was prepared from the shell of M. modiolus and the percent yield of chitosan was 10.21 ± 0.8% from 100 g of chitin. The yield of chitin in the present study is higher than the yield of chitin from the shell and operculum of N. crepidularia, (23.91 and 35.43%),20 from chiton shell (4.3%), tiger prawn (16.75%), Jinga shrimp (19.13%), blue swimming crab (20.8% for males and 20.14% for females), scyllarid lobster (21.26%), and cuttlefish (7.4%) in the Persian Gulf.34 The amount of chitosan extracted from the horse mussel in the present study is low when compared to crab shells (30–36.7%).9 Kiruba et al.(35) reported a yield of 38.23% of chitosan from mud crab Scylla serrata. The average chitosan of 73.3 ± 4.5 and 71.6 ± 5.1% was derived from prawn and crab chitin, respectively.18

Characterization of Chitosan

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

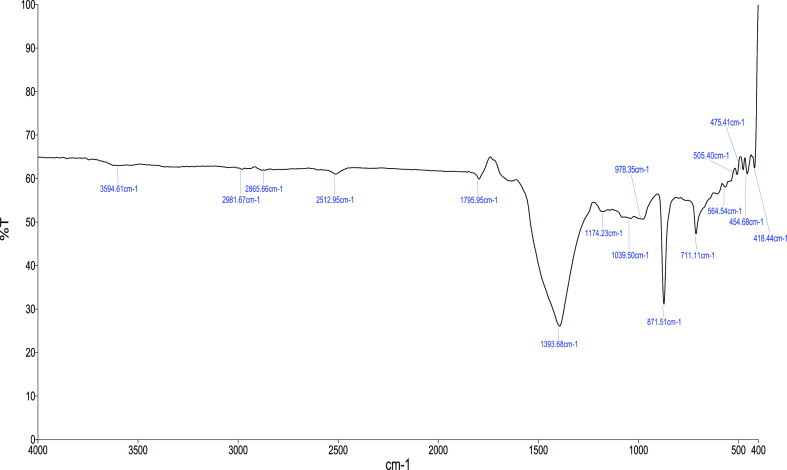

Chitosan FTIR spectra showed sharp peaks at 564 cm–1 (out-of-plane bending NH, out-of-plane bending C–O), 711 cm–1 (out-of-plane bending NH), 1174 cm–1 (C–O–C stretching), 2865 cm–1 (CH2 stretching), and 3594 cm–1 (−OH stretching). Vibrational mode of amide C=O stretching was observed at 1604, 1598, and 1592 cm–1. The spectra were also compared with the standard chitosan and correlations were observed in the spectra (Figure 1). Vibration patterns obtained from the FTIR spectrum indicate the functional groups present such as carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen. The FTIR spectra formed characteristic bands in the frequency range between 4000 and 400 cm–1.

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of the chitosan extracted from M. modiolus.

The characterization of chitosan with FTIR yielded results similar to those obtained in the studies conducted earlier.11,21,36 FTIR studies of shrimp shell waste recorded chitosan spectra at 1029 cm–1 corresponding to the free amino group at C2 of glucosamine.19 A significant peak at 1375 cm–1 of chitosan was observed corresponding to C–O starch in the primary alcoholic group. Saraswathy et al.(37) have observed a major absorption band between 1220 and 1020 cm–1, representing the free amino group (−NH2) at glucosamine C2 position in Scylla tranquebarica. In the M. edulis chitosan spectrum, a peak at 863 cm–1 was ascribed to C–N stretching, absorption peaks at 1019 and 1063 cm–1 were allotted to C–O glucose bending, while those at 1421 and 1486 cm–1 were corresponding to the C–H side chain bending—CH2OH.20 The OH stretching frequency emerged at 3452 cm–1 and also the CO (amide) and NH primary amine bends were observed at 1638 cm–1 in S. pharaonis.22

DDA and Molecular Weight of Chitosan

The DDA of chitosan extracted from horse mussel M. modiolus was calculated from the FTIR studied and was observed to be 57.43%. Previous studies state that the deacetylation of chitosan is based on the ratio of the absorbance of the amide group to that of the hydroxyl group.38 Unlike chitin, chitosan has a large proportion of an extremely protonated free amino group, which tends to attract ionic compounds. It is also the justification for its solubility to inorganic acids. Extremely toxic solvents such as lithium chloride and dimethylacetamide are used to dissolve chitin, while chitosan is soluble in dilute acetic acid. In many chemical reactions, chitosan has a free amino group as active sites. A higher DA of 77% was achieved from shrimp shells. The deacetylation rate for M. edulis (69.60 ± 0.12%) was higher than for L. attenuatum (37.30 ± 0.31).21 Al-Hassan39 recorded 54.65% deacetylation in shrimp shell, which is intermediate to the two exoskeletons tested. Muñoz et al.(40) observed a deacetylation rate of 73.6% in Aspergillus niger mycelium. Hussain et al.(38) measured the DDA as 54.6, 60.5, and 84.7% for the untreated sample, the 4 h treated, and 8 h treated alkali samples. The low DDA in this study may be attributed to the concentration of alkali, period of alkali treatment, chitin tension, and nonpulverization during deacetylation.41,42

The molecular weight of chitosan extracted from the mollusc M. modiolus was calculated to be 345.94 kDa, which is similar to the result obtained in the study conducted by Shanmugham et al.(43) Previous studies show that the molecular weight of chitosan extracted from crabs was in the range of 483–526 kDa, which decreased with prolonged reaction time. The molecular weight of chitosan is an important parameter for the application in biomedical fields. The molecular weight of chitosan varies with respect to the difference in DDA and the source of chitosan. The other factors that affect the molecular weight of chitosan are the factors in the production such as high temperature, concentration of alkali, reaction time, previous treatment of the chitin, particle size, chitin concentration, dissolved oxygen concentration, and shear stress.43

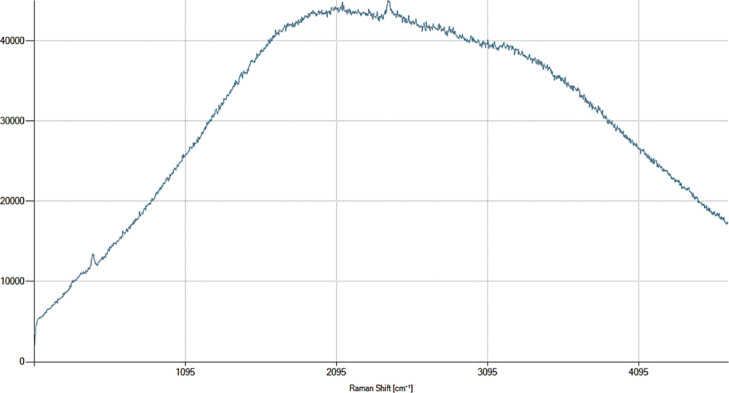

Micro-Raman Spectroscopy

The Raman shift of chitosan was observed in the range of 1095–4095 cm–1. The extracted chitosan showed maximum peaks at 484 cm–1(14,264 counts/s), 2138 cm–1 (45,061 counts/s), and 2447 cm–1 (45,636 counts/s) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Raman shift of chitosan extracted from the horse mussel M. modiolus.

The Raman shifts observed in the present study at 2447 and 484 cm–1 are similar to those observed in S. pharaonis.22 The maximum peak of chitosan extracted from the shell of S. pharaonis was observed between 2095 and 3095 cm–1. Studies have reported a linear variation in the Raman spectrum of chitosan at 2178 cm–1 when compared to standard chitosan shifts at 1774 and 1929 cm–1. The weak spectral peaks at 446, 479, and 507 cm–1 are the major indicators of the disintegration of vibrations of O=S=O groups.36 Sagheer et al.(34) and Rasti et al.(17) have reported five sharp peaks, which were similar to those obtained in the present study.

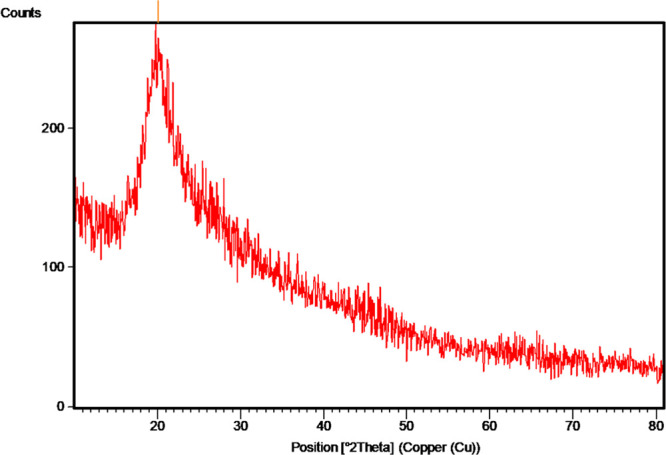

X-Ray Powder Diffraction

The XRD studies of chitosan showed a peak at 20.04° (113.92 counts/s) (Figure 3). Similar results were obtained in previous studies with five sharp crystalline reflections.17 The sharper peaks at 20.92° for chitosan obtained in the present study are evidence of a denser crystalline structure.19 Another study reported that the stronger reflection for chitosan at around 30–35° is almost similar to those obtained in the present study.17

Figure 3.

XRD of chitosan extracted from the horse mussel M. modiolus.

Elemental Analysis

Elemental analysis of chitin and chitosan revealed varying levels of nitrogen (6.59%), carbon (11.29%), hydrogen (0.83%), and sulfur (1.85%) (Table 1). The study showed a considerable decrease in the percentage of nitrogen and carbon after the transformation of chitin to chitosan while the percentage of hydrogen and sulfur was found to be higher in chitosan when compared to that of chitin. Studies on the elemental composition of chitosan from S. pharaonis revealed organic matter comprising C (42.9%), H (6.78%), and N (5.7%).22

Table 1. Elemental Composition of Chitosan from Horse Mussel M. modiolus.

| sample | weight (mg) | nitrogen (%) | carbon (%) | hydrogen (%) | sulfur (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| chitin | 5.48 | 10.12 | 12.63 | 0.39 | 1.02 |

| chitosan | 2.55 | 6.59 | 11.29 | 0.83 | 1.85 |

Antimicrobial Activity

The antimicrobial activity of the extracted chitosan was noticeable against all of the five Gram-negative and two Gram-positive bacteria examined (Table 2). Every bacterium was exposed to different concentrations of the extracted chitosan (50–200 μg/mL). The antimicrobial activity of chitosan against Escherichia coli, as prevalent from the inhibition zone, was greater at a concentration of 200 μg/mL (9 mm), followed by Bacillus subtilis (8 mm) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7 mm). The antibacterial activity of the extracted chitosan against Klebsiella pneumonia, Staphylococcus aureus, and Shigella dysenteriae was notably higher at 150 μg/mL concentration (6, 5, and 4 mm, respectively), which did not increase further with high chitosan concentrations. Overall, 150 and 200 μg/mL concentrations of the chitosan tested were efficient in terms of zone of inhibition against all the bacterial strains studied.

Table 2. Antimicrobial Activity of Chitosan Extracted from Horse Mussel M. modiolus.

| zone

of inhibition (mm) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| species | positive control | negative control | 50 (μg/mL) | 100 (μg/mL) | 150 (μg/mL) | 200 (μg/mL) |

| Gram Negative | ||||||

| E. coli | 11 | 5 | 9 | |||

| P. aeruginosa | 10 | 2 | 4 | 7 | ||

| K. pneumonia | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6 | ||

| S. typhi | 5 | 5 | 7 | |||

| S. dysenteriae | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | |

| Gram Positive | ||||||

| S. aureus | 4 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 6 | |

| B. subtilis | 4 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 9 | |

These results apparently present the antimicrobial activity of chitosan extracted from M. modiolus against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The hydrophobic character of chitosan increases with a greater number of N-acetyl groups.10,22,44,45 Earlier studies indicated that chitosan and its products have shown to have a greater influence on the cell wall degradation. Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus, B. subtilis, Sarcinia lutea) were much more susceptible to chitosan treatment than Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, Serratia marcescens).13 Increased antimicrobial activity has been witnessed against various strains of fungi, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, especially for S. aureus and E. coli, with chitosan having a lower DA or a higher number of free amino groups.7

Conclusions

The horse mussel is mainly acquired as by-catch and is discarded as a waste material. Such wastes may be used for production of the biopolymer, chitosan. Chitosan extracted from the horse mussel was characterized with FTIR, micro-Raman, XRD, and elemental analysis. The DA (57.43%) of the extracted chitosan is comparable with the previous studies on crustacean and is higher than in other molluscan species, witnessing the future prospective of chitosan from the horse mussel as a biopolymer. The present study also reports notable antibacterial activity of chitosan at a 200 μg/mL concentration against E. coli (9 mm) and B. subtilis (8 mm) among the Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria tested. Studies are underway to elucidate the antimicrobial activity of chitosan over a wide range of microbes and the extraction of antimicrobial proteins from the horse mussel, M. modiolus.

Experimental Section

Collection of Horse Mussel Shells

The waste shells of horse mussels were collected with the help of the local fishermen from Thondi coast (9°45′ N, 79°4′ E) (Figure 4). The shells were washed, dried, and pulverized for the extraction of chitin and chitosan.

Figure 4.

Dorsal view of the horse mussel M. modiolus.

Extraction of Chitin and Chitosan

The extraction of chitin from shells involves decolorization, demineralization, and deproteinization.36 For the decolorization process, the sample was refluxed in 10 mL of sodium hypochlorite solution at 100 °C for 10 min. This step was repeated for maximum decolorization. The shells were demineralized by mixing the sample for 15 min at 70 °C with 20 mL of 1 M hydrochloric acid. The sample was deproteinized by refluxing the sample with 20 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) at 100 °C for 20 min. The sample was then washed thoroughly with distilled water until the pH of the sample was neutralized and was dried at room temperature to obtain chitin. The chitin obtained was refluxed in 15 mL of 45% NaOH17 at 110 °C for 24 h. The resulting product was washed in distilled water until the pH was neutralized and filtered to get chitosan.

Characterization of Chitosan

The harvested chitosan sample was subjected to FTIR by diligent blending with KBr and then pressing the dried mixture to result in a homogeneous sample/KBr disk. Infrared spectra of KBr-supported chitosan were measured over the frequency range of 4000–400 cm–1 at a resolution of 4 cm–1 using a Perkins-Elmer spectrometer (Spectrum RX I, MA, USA). The DA was determined in triplicate from FTIR.17

where A1795 represents the degree of absorption at 1795 cm–1 and A3594 represents the degree of absorption at 3594 cm–1.

The molecular weight of chitosan extracted from the horse mussel was determined by the use of a viscometric method. The viscosity of the chitosan was measured with an Ostwald capillary viscometer. The sample was dissolved in 0.3 M acetic acid and 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer, and the average molecular weight (Mv) of chitosan was calculated by measuring the intrinsic viscosity (η) as proposed by the Mark–Houwink–Kuhn–Sakurada equation43

where k and a are the viscometric coefficients, which are greatly dependent on the polymer, the solvent used, and the temperature parameters.43Mv stands for the average molecular weight and η stands for the intrinsic viscosity. For the chitosan solution made of 0.3 M acetic acid and 0.2 M sodium acetate buffer (at 25 °C), the value of k is 1.38 × 10–5 and a = 0.85.

Micro-Raman chitosan spectra were measured using an argon laser to analyze the vibration modes of films under an excitation wavelength of 632 nm (Princeton Instrument Action SP 2500, Japan). XRD studies of chitosan were carried out to detect its crystallinity using an X’Pert PRO PAN analytical (The Netherlands) instrument operated at 40 kV and 30 mA with Cu Kα = 1.5406 Å. The comparative crystalline phase of the chitosan was determined by dividing the area under the curve into the total region of the crystallographic peaks. Elemental analysis of the processed chitin and chitosan was done using Vario micro cube CHNS (Elementar, Germany) to determine the amount of C and N. The samples were heated to a temperature of 1000 °C, and 2 mg of the product was coated with a tin boat and was introduced to the elemental analyzer for combustion in the presence of helium and oxygen gases.

Antimicrobial Activity

Isolation and Identification of Bacteria

One milliliter of seawater was serially diluted with sterile seawater. For the isolation and enumeration of bacteria present in the seawater sample, spread plate technique (Cappuccino and Sherman, 2001) was employed. The serially diluted seawater samples were inoculated on Zobell marine agar plates and incubated at 37 °C overnight. After incubation, the bacterial colonies were picked carefully on the basis of colony morphology that includes size, shape, and color. The isolated bacterial colonies were identified as per the procedure of Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (Brenner et al., 2005). Morphological parameters such as Gram staining and motility tests were carried out. Motility was observed using the “Hanging drop method”. Biochemical characterization tests such as indole, methyl red, Voges–Proskauer, citrate utilization, triple sugar iron agar test, catalase, starch hydrolysis, protein hydrolysis, lipid hydrolysis, coagulase, oxidase, and urease were performed for the identification of bacteria. The above studies revealed the presence of E. coli, S. aureus, B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, Salmonella typhi, and S. dysenteriae in the seawater sample.

The antibacterial activity ofchitosan against the isolated bacterial strains was studied by the well diffusion method. Chitosan was dissolved in deionzed water and constantly stirred until a uniform colloidal suspension was obtained.18 To the yield, a liquid concentration of 50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL of the sample and stock solution (1 mg/mL) were dissolved in appropriate amounts of 0.1% acetic acid. The nutrient medium was prepared by dissolving Muller Hinton agar (5.3 g) in 100 mL of distilled water and sterilized at 121 °C for about 15–20 min. The sterilized medium was then poured onto the sterilized plates to assess the antimicrobial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, B. subtilis, P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae, S. typhi, and S. dysenteriae. An appropriate volume of these bacteria was swabbed gently on the nutrient broth medium and equitized wells were created. Chitosan samples of different concentrations (50, 100, 150, and 200 μg/mL) were injected into the respective wells along with positive and negative control. Acetic acid (0.1%) was used as negative control, and for positive control (30 μg/mL) tetracycline (E. coli, S. aureus), cefuroxime (B. subtilis), and ceftriaxone (K. pneumonia, S. typhi, S. dysenteriae) were used. The plates were incubated overnight at 32 °C and the zones of inhibition were then measured in millimeters, and the best range was proposed from 50 to 200 μg/mL of samples.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support received from RUSA 2.0 [F.24-51/2014-U, Policy (TN Multi-Gen), Department of Education, Govt. of India]. R.V. is thankful to RUSA 2.0 for financial assistance rendered in the form of a RUSA TBRP Project Fellowship.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Minke R.; Blackwell J. The structure of α-chitin. J. Mol. Biol. 1978, 120, 167–181. 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo D.-N.; Kim M.-M.; Kim S.-K. Chitin oligosaccharides inhibit oxidative stress in live cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2008, 74, 228–234. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaudo M. Chitin and chitosan: Properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2006.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitoyannis I. S.; Nakayama A.; Aiba S.-i. Chitosan and gelatin based edible films: State diagrams, mechanical and permeation properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 1998, 37, 371–382. 10.1016/s0144-8617(98)00083-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haque T.; Chen H.; Ouyang W.; Martoni C.; Lawuyi B.; Urbanska A. M.; Prakash S. Superior cell delivery features of polyethylene glycol incorporated alginate, chitosan, and poly-L-lysine microcapsules. Mol. Pharm. 2005, 2, 29–36. 10.1021/mp049901v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J.; Chen F.; Wang X.; Rajapakse N. C. Effect of chitosan on the biological properties of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 3696–3701. 10.1021/jf0480804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeeck R. M. H.; Haiben M.; Thin H. P.; Verbeek F. Solubility and solution behaviour of strontium hydroxyapatite. Z. Phys. Chem. 1977, 108, 203–215. 10.1524/zpch.1977.108.2.203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K.; Akiba Y.; Shibuya T.; Kashiwada A.; Matsuda K.; Hirata M. Removal of phenol compounds by the combined use of tyrosinase and chitosan. Abstr. Pap. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 230, U4039. [Google Scholar]

- Yen M.-T.; Yang J.-H.; Mau J.-L. Physicochemical characterization of chitin and chitosan from crab shells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 75, 15–21. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2008.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elassal M.; El-Manofy N. Chitosan nanoparticles as drug delivery system for cephalexin and its antimicrobial activity against multiidrug resistent bacteria. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 11, 14–27. 10.22159/ijpps.2019v11i7.33375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Antonino R. S. C. M. Q.; Fook B. R. P. L.; Lima V. A. O. L.; Rached R. F.; Lima E. P. N.; Lima R. J. S.; Covas C. A. P.; Fook M. V. L. Preparation and characterization of chitosan obtained from shells of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei Boone). Mar. Drugs. 2017, 15, 141. 10.3390/md15050141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavall R.; Assis O.; Campanafilho S. β-Chitin from the pens of Loligo sp.: extraction and characterization. Bioresour. Technol. 2007, 98, 2465–2472. 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinsova J.; Vavrikova E. Chitosan derivatives with antimicrobial, antitumour and antioxidant activities - a review. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2011, 17, 3596–3607. 10.2174/138161211798194468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag R. K.; Mohamed R. R. Synthesis and characterization of carboxymethyl chitosan nanogels for swelling studies and antimicrobial activity. Molecules 2013, 18, 190–203. 10.3390/molecules18010190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart B. H.Infrared Spectroscopy: Fundamentals and Applications; Analytical Techniques in the Sciences (AnTs) Series; Wiley, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ren X. D.; Liu Q. S.; Feng H.; Yin X. Y. The characterization of chitosan nanoparticles by Raman spectroscopy. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 665, 367–370. 10.4028/www.scientific.net/amm.665.367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rasti H.; Parivar K.; Baharara J.; Iranshahi M.; Namvar F. Chitin from the mollusc chiton: extraction, characterization and chitosan preparation. Iran J. Pharm. Res. 2017, 16, 366–379. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raja P.; Chellaram C.; John A. A. Antibacterial properties of chitin from shell wastes. Indian J. Innov. Dev. 2012, 1, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Divya K.; Rebello S.; Jisha M. S.. A simple and effective method for extraction of high purity chitosan from shrimp shell waste. International Conference on Advanced Applied Science Environment Engineering, 2014; pp 141–145.

- Palpandi C.; Shanmugam V.; Shanmugam A. Extraction of chitin and chitosan from shell and operculum of mangrove gastropod Nerita crepidularia Lamarck. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 1, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Majekodunmi S. O.; Olorunsola E. O.; Uzoaganobi C. C. Comparative physicochemical characterization of chitosan from shells of two bivalved mollusks from two different continents. Am. J. Polym. Sci. 2017, 7, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Karthik R.; Manigandan V.; Saravanan R.; Rajesh R. P.; Chandrika B. Structural characterization and in vitro biomedical activities of sulfated chitosan from Sepia pharaonis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 84, 319–328. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner D. J.Introduction to Raman Scattering; Springer: Berlin, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari S.; Rath P. K. Extraction and characterization of chitin and chitosan from (Labeo rohit) fish scales. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 482–489. 10.1016/j.mspro.2014.07.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H. Y.; Jiang R.; Xiao L.; Zeng G. M. Preparation, characterization, adsorption kinetics and thermodynamics of novel magnetic chitosan enwrapping nanosized γ-Fe2O3 and multi-walled carbon nanotubes with enhanced adsorption properties for methyl orange. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 5063–5069. 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S.; Sun J.; Yu L.; Zhang C.; Bi J.; Zhu F.; Qu M.; Jiang C.; Yang Q. Extraction and characterization of chitin from the beetle Holotrichia parallela motschulsky. Molecules 2012, 17, 4604–4611. 10.3390/molecules17044604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahariah P.; Másson M. Antimicrobial chitosan and chitosan derivatives: a review of the structure-activity relationship. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 3846–3868. 10.1021/acs.biomac.7b01058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman M.; Juneja V. K. Review of antimicrobial and antioxidative activities of chitosans in food. J. Food Protect. 2010, 73, 1737–1761. 10.4315/0362-028x-73.9.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin T. J.Biochemistry of Antimicrobial Action; Springer: Nethrelands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Kong M.; Chen X. G.; Xing K.; Park H. J. Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and mode of action: a state of the art review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 51–63. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin C.; Du Y.; Xiao L.; Li Z.; Gao X. Enzymic preparation of water-soluble chitosan and their antitumor activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2002, 31, 111–117. 10.1016/s0141-8130(02)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johney J.; Eagappan K.; Ragunathan R. R. Microbial extraction of chitin and chitosan from Pleurotus spp, its characterization and antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Curr. Pharm. Res. 2016, 9, 88–93. 10.22159/ijcpr.2017v9i1.16623. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar N. A.; Richardson C. A.; Seed R. Age determination, growth rate and population structure of the horse mussel Modiolus modiolus. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 1990, 70, 441–457. 10.1017/s0025315400035529. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Sagheer F. A.; Al-Sughayer M. A.; Muslim S.; Elsabee M. Z. Extraction and characterization of chitin and chitosan from marine sources in Arabian Gulf. Carbohydr. Polym. 2009, 77, 410–419. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2009.01.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kiruba A.; Uthayakumar S.; Munirasu S.; Ramasubramanian V. Extraction, characterisation and physicochemical properties of chitin and chitosan from mud crab shell, Scylla serrata. Indian J. Appl. Res. 2013, 3, 44–46. 10.15373/2249555x/aug2013/14. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya M.; Baran T.; Karaarslan M. A new method for fast chitin extraction from shells of crab, crayfish and shrimp. Nat. Prod. Res. 2015, 29, 1477–1480. 10.1080/14786419.2015.1026341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraswathy G.; Pal S.; Rose C.; Sastry T. P. A novel bio-inorganic bone implant containing deglued bone, chitosan and gelatin. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2001, 24, 415–420. 10.1007/bf02708641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R.; Iman M.; Maji T. K. Determination of degree of deacetylation of chitosan and their effect on the release behavior of essential oil from chitosan and chitosan-gelatin complex microcapsules. Rev. Téc. Ing. Univ. Zulia. 2014, 37, 69–77. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hassan A. A. Utilization of waste: extraction and characterization of chitosan from shrimp byproducts. Civ. Environ. Res. 2016, 8, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz G.; Valencia C.; Valderruten N.; Ruiz-Durántez E.; Zuluaga F. Extraction of chitosan from Aspergillus niger mycelium and synthesis of hydrogels for controlled release of betahistine. React. Funct. Polym. 2015, 91–92, 1–10. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2015.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowska-Biskup R.; Jarosińska D.; Rokita B.; Ulański P.; Rosiak J. M. Determination of degree of deacetylation of chitosan - comparision of methods. Prog. Chem. Appl. Chitin. Deriv. 2012, 12, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. S.; Iqbal A. Production and characterization of chitosan from shrimp waste. J. Bangladesh Agric. Univ. 2014, 12, 153–160. 10.3329/jbau.v12i1.21405. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam A.; Subhapradha N.; Suman S.; Ramasamy P.; Saravanan R.; Shanmugam V.; Srinivasan A.. Characterization of biopolymer “chitosan” from the shell of donacid clam Donax scortum (Linnaeus, 1758) and its antioxidant activity. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2012, 4 , 460−465. [Google Scholar]

- Packirisamy R. G.; Govindasamy C.; Sanmugam A.; Karuppasamy K.; Kim H. S.; Vikraman D. Synthesis and antibacterial properties of novel ZnMn2O4–chitosan nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1589. 10.3390/nano9111589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabea E. I.; Badawy M. E.-T.; Stevens C. V.; Smagghe G.; Steurbaut W. Chitosan as antimicrobial agent: applications and mode of action. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4, 1457–1465. 10.1021/bm034130m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]